Validating Likelihood Ratio Methods: A Framework for Forensic Evidence and Drug Safety

This article provides a comprehensive framework for the validation of Likelihood Ratio (LR) methods, addressing critical needs in both forensic science and pharmacovigilance.

Validating Likelihood Ratio Methods: A Framework for Forensic Evidence and Drug Safety

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for the validation of Likelihood Ratio (LR) methods, addressing critical needs in both forensic science and pharmacovigilance. It explores the foundational principles of LR and the current empirical challenges in forensic validation. The piece details methodological applications, from drug safety signal detection to diagnostic interpretation, and offers solutions for common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, such as handling zero-inflated data and presenting complex statistics. Finally, it synthesizes established scientific guidelines and judicial standards for rigorous validation, providing researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with the tools to assess, apply, and defend LR methodologies with scientific rigor.

The What and Why: Core Principles and the Urgent Need for LR Validation

The Likelihood Ratio (LR) is a fundamental statistical measure used to quantify the strength of evidence, finding critical application in two distinct fields: medical diagnostic testing and forensic science. In both domains, the LR serves a unified purpose: to update prior beliefs about a proposition in light of new evidence. Formally, the LR represents the ratio of the probability of observing a specific piece of evidence under two competing hypotheses. In diagnostics, these hypotheses typically concern the presence or absence of a disease, while in forensics, they often address prosecution versus defense propositions regarding source attribution [1] [2]. This comparative guide examines the operationalization, interpretation, and validation of LR methodologies across these fields, highlighting both convergent principles and divergent applications to support researchers in validating LR methods for forensic evidence research.

The mathematical foundation of the LR is expressed as:

- LR = Pr(E | H₁) / Pr(E | H₂)

Here, Pr(E | H₁) represents the probability of observing the evidence (E) given that the first hypothesis (H₁) is true, while Pr(E | H₂) is the probability of the same evidence given the second, competing hypothesis (H₂) is true [2]. A LR greater than 1 supports H₁, a value less than 1 supports H₂, and a value of 1 indicates the evidence does not distinguish between the two hypotheses. The further the LR is from 1, the stronger the evidence.

LR Calculation and Interpretation Frameworks

Core Definitions and Formulae by Field

The calculation and presentation of the LR differ between diagnostic and forensic contexts due to their specific operational needs. The following table summarizes the key formulae and their components.

Table 1: Likelihood Ratio Formulae in Diagnostic and Forensic Contexts

| Aspect | Diagnostic Testing | Forensic Science |

|---|---|---|

| Competing Hypotheses | H₁: Disease is Present (D+)H₂: Disease is Absent (D-) | Hₚ: Prosecution Proposition (e.g., same source)Hd: Defense Proposition (e.g., different source) |

| Positive/Forensic Evidence | Positive Test Result (T+) | Observed Forensic Correspondence (E) |

| LR for Evidence | Positive LR (LR+) = Pr(T+ | D+) / Pr(T+ | D-)Which is equivalent to:LR+ = Sensitivity / (1 - Specificity) [1] [3] |

LR = Pr(E | Hₚ) / Pr(E | Hd) [2] [4] |

| Negative/Exculpatory Evidence | Negative Test Result (T-) | N/A (The same formula is used, but the result is a low LR value) |

| LR for Negative/Exculpatory Evidence | Negative LR (LR-) = Pr(T- | D+) / Pr(T- | D-)Which is equivalent to:LR- = (1 - Sensitivity) / Specificity [3] |

Interpretation of LR Values

The interpretation of the LR's strength is standardized, though the implications are context-dependent. The table below provides a general guideline for interpreting LR values.

Table 2: Interpretation of Likelihood Ratio Values

| Likelihood Ratio Value | Interpretation of Evidence Strength | Approximate Change in Post-Test/Posterior Probability |

|---|---|---|

| > 10 | Strong evidence for H₁ / disease / Hₚ | Large Increase [1] [3] |

| 5 - 10 | Moderate evidence for H₁ / disease / Hₚ | Moderate Increase (~30%) [3] |

| 2 - 5 | Weak evidence for H₁ / disease / Hₚ | Slight Increase (~15%) [3] |

| 1 | No diagnostic or probative value | No change |

| 0.5 - 0.2 | Weak evidence for H₂ / no disease / Hd | Slight Decrease (~15%) [3] |

| 0.2 - 0.1 | Moderate evidence for H₂ / no disease / Hd | Moderate Decrease (~30%) [3] |

| < 0.1 | Strong evidence for H₂ / no disease / Hd | Large Decrease [1] [3] |

In diagnostic medicine, LRs are used to update the pre-test probability of a disease, yielding a post-test probability. This is often done using Bayes' theorem, which can be visually assisted with a Fagan nomogram [1]. In forensic science, the LR directly updates the prior odds of the prosecution's proposition relative to the defense's proposition to posterior odds [2]. The fundamental logical relationship is:

Experimental Protocols for LR Method Validation

Protocol for Diagnostic Test Comparison

Comparing the accuracy of two binary diagnostic tests in a paired design involves specific methodologies for calculating confidence intervals and sample sizes.

- 1. Study Design: A paired design is employed where each patient in a sample of size N receives both the new diagnostic test and the comparator test. The disease status is determined by a gold standard.

- 2. Data Collection: Results are tabulated into multiple 2x2 tables, capturing the outcomes of both tests for subjects with and without the disease.

- 3. Parameter Calculation: For each test, sensitivity and specificity are calculated. The Positive LR (LR+) and Negative LR (LR-) for each test are then derived as LR+ = Sensitivity / (1 - Specificity) and LR- = (1 - Sensitivity) / Specificity [3] [5].

- 4. Comparison Metric: The ratio of the LRs (e.g., LR+ of Test A / LR+ of Test B) is the key comparison parameter. Six approximate confidence intervals can be constructed for this ratio to assess the precision of the estimate [5].

- 5. Sample Size Determination: The required sample size is calculated to ensure that the estimated ratio of LRs is within a pre-specified precision (margin of error) with a certain confidence level [5].

Protocol for Forensic Familial DNA Testing

A novel classification-driven LR method was developed to address population substructure in familial DNA searches, a key advancement for validation.

- 1. Challenge: Traditional LR statistics for inferring genetic relationships assume a uniform genetic background, which is unrealistic in structured populations, leading to potential inaccuracies [6].

- 2. Proposed Method (LRCLASS): This method incorporates a classification step to handle nuisance parameters arising from unknown subpopulation origins.

- 3. Experimental Workflow:

- 4. Validation: The power of LRCLASS (e.g., for detecting full-sibling relationships) is compared against existing methods like LRLAF, LRMAX, LRMIN, and LRAVG. The analysis demonstrated that LRCLASS paired with Naive Bayes classification exhibited higher statistical power in the Thai population [6].

Protocol for Assessing Model Fit with Conditional Likelihood Ratio Test

The Conditional Likelihood Ratio Test (LRT) is used in model evaluation, such as assessing item fit in Rasch models, but requires careful validation of its error rates.

- 1. Simulation: A dataset is simulated where all items are known to fit the statistical model (e.g., the Rasch model), creating a "true negative" scenario.

- 2. Bootstrapping: A non-parametric bootstrap procedure with a high number of iterations (e.g., 5000) is applied to the dataset using the LRT function.

- 3. False Positive Rate Calculation: The percentage of bootstrap iterations where the LRT incorrectly indicates a significant misfit (a false positive) is calculated. This is repeated across varying sample sizes (n = 150, 250, 500, 1000, 1500, 2000) and numbers of test items (e.g., 10 vs. 19 items) [7].

- 4. Validation Insight: The experiment reveals that the false positive rate of the LRT often exceeds the nominal 5% level, especially with larger sample sizes and a higher number of items. This cautions researchers against over-reliance on the LRT alone for determining model fit and underscores the need for sample size considerations in validation studies [7].

Critical Analysis and Research Challenges

The "Best Way" to Present LRs

A central challenge in forensic science is effectively communicating the meaning of LRs to legal decision-makers. A critical review of existing literature concludes that there is no definitive answer on the best format—be it numerical LRs, verbal equivalents, or other methods—to maximize understandability [8]. This highlights a significant gap between statistical validation and practical implementation. Future research must develop and test methodologies that bridge this communication gap, ensuring that the validated weight of evidence is accurately perceived and utilized in legal contexts [8].

The Logical Necessity of the LR Paradigm

Countering the view that the LR is merely "one possible" tool for communication, a rigorous mathematical argument demonstrates that it is the only logically admissible form for evaluating evidence under very reasonable assumptions [2]. The argument shows that the value of evidence must be a function of the probabilities of the evidence under the two competing propositions, and that the only mathematical form satisfying the core principle of irrelevance (where unrelated evidence does not affect the value of the original evidence) is the ratio Pr(E | Hₚ) / Pr(E | Hd) [2]. This provides a foundational justification for its central role in evidence validation.

Quantitative vs. Qualitative Reporting

A key distinction exists in reporting practices. In diagnostics, LRs are almost exclusively reported as numerical values. In forensics, while numerical LRs are the basis of calculation, reporting may sometimes use verbal scales (e.g., "moderate support," "strong support") for communication, though this practice is subject to ongoing debate regarding its precision and potential for misinterpretation [8].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for LR Method Validation

| Item / Solution | Function / Application in LR Research |

|---|---|

| Reference Databases with Population Metadata | Provides allele frequencies or other population data essential for calculating LRs, particularly for methods like LRCLASS that account for population substructure [6]. |

| Statistical Software (R, Python with SciPy/NumPy) | Platform for implementing bootstrap simulations for LRTs [7], calculating confidence intervals for LRs [5], and developing custom classification algorithms [6]. |

| Gold Standard Reference Data | Critical for diagnostic test validation. Provides the ground truth (disease present/absent) against which the sensitivity and specificity of a new test are measured for LR calculation [5]. |

| Simulated Datasets with Known Properties | Allows for controlled evaluation of statistical methods, such as testing the false positive rates of the Conditional LRT under ideal fitting conditions [7]. |

| Classification Algorithms (e.g., Naive Bayes) | Used in advanced LR methodologies to classify evidence into predefined groups (e.g., subpopulations) to improve the accuracy and robustness of the calculated LR [6]. |

| Bootstrap Resampling Code | A computational procedure used to estimate the sampling distribution of a statistic (like the LRT), enabling the assessment of reliability and error rates without relying solely on asymptotic theory [7]. |

The Likelihood Ratio serves as a universal paradigm for evidence evaluation, with its core mathematical principle remaining consistent across diagnostic and forensic fields. However, its application, calculation specifics, and communication strategies are finely tuned to the specific needs and challenges of each domain. For researchers focused on the validation of LR methods for forensic evidence, the key takeaways are the necessity of robust experimental protocols to account for real-world complexities like population structure, the critical importance of understanding and controlling for statistical properties like false positive rates, and the recognition that technical validation must be coupled with research into effective communication to ensure the LR fulfills its role in the justice system.

Forensic science stands at a critical intersection of science and law, where decisions based on expert testimony can fundamentally alter human lives. The scientific and legal imperative for validation of forensic methods has emerged from decades of scrutiny, culminating in landmark reports from prestigious scientific bodies. Validation ensures that forensic techniques are not just routinely performed but are scientifically sound, reliable, and accurately presented in legal proceedings. This mandate for validation has evolved from theoretical concern to urgent necessity following critical assessments of various forensic disciplines.

The journey toward rigorous validation standards began with the groundbreaking 2009 National Research Council (NRC) report, "Strengthening Forensic Science in the United States: A Path Forward," which revealed startling deficiencies in the scientific foundations of many forensic disciplines [9]. This was followed by the pivotal 2016 President's Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST) report, which specifically addressed the need for empirical validation of feature-comparison methods [9]. These reports collectively established that without proper validation studies to measure reliability and error rates, forensic science cannot fulfill its duty to the justice system. The recent PCAST reports from 2022-2025 continue to emphasize the crucial role of science and technology in empowering national security and justice systems, reinforcing the ongoing need for rigorous validation frameworks [10].

Foundational Reports: NAS and PCAST Assessments

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) Report (2009)

The 2009 NAS report, "Strengthening Forensic Science in the United States: A Path Forward," represented a watershed moment for forensic science. This comprehensive assessment revealed that many forensic disciplines, including bitemark analysis, firearm and toolmark examination, and even fingerprint analysis, lacked sufficient scientific foundation. The report concluded that with the exception of DNA analysis, no forensic method had been rigorously shown to consistently and with high degree of certainty demonstrate connection between evidence and specific individual or source.

The NAS report identified several critical deficiencies: inadequate validation of basic principles, insufficient data on reliability and error rates, overstatement of findings in court testimony, and systematic lack of standardized protocols and terminology. Among its key recommendations was the urgent call for research to establish validity and reliability, development of quantifiable measures for assessing evidence, and establishment of rigorous certification programs for forensic practitioners.

The President's Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST) Report (2016)

Building upon the NAS report, the 2016 PCAST report provided a more focused assessment of feature-comparison methods, evaluating whether they meet the scientific standards for foundational validity. PCAST defined foundational validity as requiring "empirical evidence establishing that a method has been repeatably and reproducibly shown to be capable of providing accurate information regarding the source" of forensic evidence [9]. The report introduced a rigorous framework for evaluating validation, emphasizing that courts should only admit forensic results from methods that are foundationally valid and properly implemented.

The PCAST report specifically highlighted that many forensic disciplines, including bitemark analysis and complex DNA mixtures, lacked sufficient empirical validation. It recommended specific criteria for validation studies, including appropriate sample sizes, black-box designs to mimic casework conditions, and measurement of error rates using statistical frameworks like signal detection theory. The report stressed that without such validation, expert testimony regarding source attributions could not be considered scientifically valid.

Table 1: Key Recommendations from NAS and PCAST Reports

| Aspect | NAS Report (2009) Recommendations | PCAST Report (2016) Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Research & Validation | Establish scientific validity through rigorous research programs | Require foundational validity based on empirical studies |

| Error Rates | Develop data on reliability and measurable error rates | Measure accuracy and error rates using appropriate statistical frameworks |

| Standardization | Develop standardized terminology and reporting formats | Implement standardized protocols for validation studies |

| Testimony Limits | Avoid assertions of absolute certainty or individualization | Limit testimony to scientifically valid conclusions supported by data |

| Education & Training | Establish graduate programs in forensic science | Enhance scientific training for forensic practitioners |

| Judicial Oversight | Encourage judicial scrutiny of forensic evidence | Provide judges with framework for evaluating scientific validity |

Validation Frameworks and Measurement Approaches

Signal Detection Theory in Forensic Validation

Signal detection theory (SDT) has emerged as a powerful framework for measuring expert performance in forensic pattern matching disciplines, providing a robust alternative to simplistic proportion-correct measures [11] [9]. SDT distinguishes between two crucial components of decision-making: discriminability (the ability to distinguish between same-source and different-source evidence) and response bias (the tendency to favor one decision over another). This distinction is critical because accuracy metrics alone can be misleading when not accounting for bias.

In forensic applications, "signal" represents instances where evidence comes from the same source, while "noise" represents instances where evidence comes from different sources [9]. The theory provides a mathematical framework for quantifying how well examiners can discriminate between these two conditions independently of their tendency to declare matches or non-matches. This approach has been successfully applied across multiple forensic disciplines, including fingerprint analysis, firearms and toolmark examination, and facial recognition.

Table 2: Signal Detection Theory Metrics for Forensic Validation

| Metric | Calculation | Interpretation | Application in Forensics |

|---|---|---|---|

| d-prime (d') | Standardized difference between signal and noise distributions | Higher values indicate better discriminative ability | Primary measure of examiner skill independent of bias |

| Criterion (c) | Position of decision threshold relative to neutral point | Values > 0 indicate conservative bias; < 0 indicate liberal bias | Measures institutional or individual response tendencies |

| AUC (Area Under ROC Curve) | Area under receiver operating characteristic curve | Probability of correct discrimination in two-alternative forced choice | Overall measure of discriminative capacity (0.5=chance to 1.0=perfect) |

| Sensitivity (Hit Rate) | Proportion of same-source cases correctly identified | Ability to identify true matches | Often confused with overall accuracy in legal settings |

| Specificity | Proportion of different-source cases correctly identified | Ability to exclude non-matches | Critical for avoiding false associations |

| Diagnosticity Ratio | Ratio of hit rate to false alarm rate | Likelihood ratio comparing match vs. non-match hypotheses | Directly relevant to Bayesian interpretation of evidence |

Experimental Design for Validation Studies

Proper experimental design is crucial for meaningful validation studies. Research has demonstrated that design choices can dramatically affect conclusions about forensic examiner performance [11]. Key considerations include:

Trial Balance: Including equal numbers of same-source and different-source trials to avoid prevalence effects that can distort performance measures.

Inconclusive Responses: Recording inconclusive responses separately from definitive decisions rather than forcing binary choices, as this reflects real-world casework and provides more nuanced performance data.

Control Groups: Including appropriate control groups (typically novices or professionals from unrelated disciplines) to establish baseline performance and demonstrate expert superiority.

Case Sampling: Randomly sampling or systematically varying case difficulties to ensure representative performance estimates rather than focusing only on easy or obvious comparisons.

Trial Quantity: Presenting as many trials as practical to participants to ensure stable and reliable performance estimates, as small trial numbers can lead to misleading conclusions due to sampling error.

These methodological considerations directly address concerns raised in both the NAS and PCAST reports regarding the need for empirically rigorous validation studies that properly measure the accuracy and reliability of forensic decision-making.

Implementation Protocols and Research Reagents

Experimental Workflow for Validation Studies

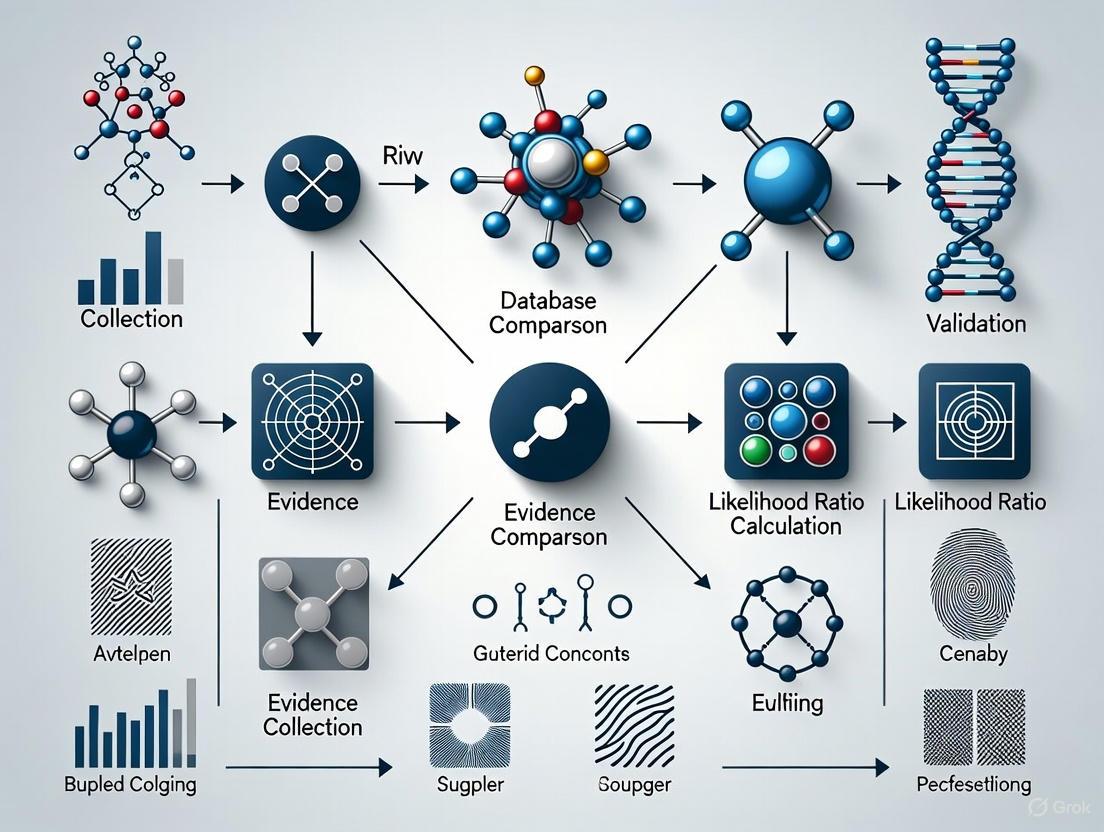

The following diagram illustrates a comprehensive experimental workflow for conducting validation studies in forensic pattern matching, incorporating best practices from signal detection theory and addressing key methodological requirements:

Diagram Title: Experimental Workflow for Forensic Validation

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Forensic Validation Studies

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Validation Research |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Material Sets | NIST Standard Reference Materials, FBI Patterned Footwear Database, Certified Fingerprint Cards | Provide standardized, ground-truth-known materials for controlled validation studies |

| Statistical Analysis Software | R with psycho package, Python with scikit-learn, MedCalc, SPSS | Calculate signal detection metrics, perform statistical tests, generate ROC curves |

| Participant Management Systems | SONA Systems, Amazon Mechanical Turk, REDCap, Qualtrics | Recruit participants, manage study sessions, track compensation |

| Experimental Presentation Platforms | OpenSesame, PsychoPy, E-Prime, Inquisit | Present standardized stimuli, randomize trial order, collect response data |

| Data Management Tools | EndNote, Covidence, Rayyan, Microsoft Access | Manage literature, screen studies, extract data, maintain research databases |

| Forensic Analysis Equipment | Comparison microscopes, Automated Fingerprint Identification Systems, Spectral imaging systems | Standardized examination under controlled conditions mimicking operational environments |

Case Applications and Research Gaps

Applied Validation Research

Applied validation studies implementing the NAS and PCAST recommendations have yielded critical insights across multiple forensic disciplines. In fingerprint examination, carefully designed black-box studies have demonstrated that qualified experts significantly outperform novices, with higher discriminability (d-prime values) and more appropriate use of inconclusive decisions [9]. However, these studies have also revealed that even experts exhibit measurable error rates, challenging claims of infallibility that have sometimes characterized courtroom testimony.

Similar research in firearms and toolmark examination has identified specific factors that influence expert performance, including the quality of the evidence, the specific features being compared, and the examiner's training and experience. Importantly, validation studies have begun to establish quantitative measures of reliability that can inform courtroom testimony, moving beyond the subjective assertions that characterized much historical forensic science. This empirical approach aligns directly with the recommendations of both NAS and PCAST for evidence-based forensic science.

Current Research Gaps and Future Directions

Despite progress, significant research gaps remain in forensic validation. The 2023-2025 PCAST reports continue to emphasize the crucial role of science and technology in addressing national challenges, including forensic validation [10]. Key research needs include:

Domain-Specific Thresholds: Establishing empirically-derived performance thresholds for what constitutes sufficient reliability in different forensic disciplines.

Context Management: Developing effective procedures for minimizing contextual bias without impeding efficient casework.

Cross-Disciplinary Harmonization: Creating standardized validation frameworks that allow meaningful comparison across different forensic disciplines.

Longitudinal Monitoring: Implementing continuous performance monitoring systems that track examiner performance over time and across different evidence types.

Computational Augmentation: Exploring how artificial intelligence and computational systems can enhance human decision-making while maintaining transparency and interpretability.

The continued emphasis in recent PCAST reports on areas such as artificial intelligence, cybersecurity, and advanced manufacturing suggests growing recognition of both the challenges and opportunities presented by new technologies in forensic science [10]. The 2024 report "Supercharging Research: Harnessing Artificial Intelligence to Meet Global Challenges" particularly highlights the potential of AI to transform scientific discovery, including in forensic applications [10].

The scientific and legal imperative for validation of forensic methods, as articulated in the NAS and PCAST reports, has fundamentally transformed the landscape of forensic science. The adoption of rigorous validation frameworks based on signal detection theory provides a pathway toward empirically-grounded, transparent, and reliable forensic practice. By implementing standardized experimental protocols, appropriate performance metrics, and continuous monitoring systems, the forensic science community can address the historical deficiencies identified by authoritative scientific bodies.

The journey toward fully validated forensic science remains ongoing, with current PCAST reports through 2025 continuing to emphasize the critical importance of science and technology in serving justice [10]. As validation research progresses, it will continue to shape not only forensic practice but also legal standards for the admissibility of expert testimony. Ultimately, robust validation protocols serve the interests of both justice and science by ensuring that conclusions presented in legal settings rest on firm empirical foundations, protecting both the rights of individuals and the integrity of the justice system.

The evaluation of forensic feature-comparison evidence is undergoing a fundamental transformation from subjective assessment to quantitative measurement using likelihood ratio (LR) methods. This shift represents a paradigm change in how forensic scientists express the strength of evidence, moving from categorical opinions to calibrated statistical statements. Despite widespread recognition of its theoretical superiority, the adoption of LR methods in operational forensic practice faces significant challenges due to limited empirical foundations across many forensic disciplines. The validation of LR methods requires demonstrating that they produce reliable, accurate, and calibrated LRs that properly reflect the evidence's strength [12].

The empirical foundation problem manifests in multiple dimensions: insufficient data for robust model development, limited understanding of feature variability in relevant populations, and inadequate validation frameworks specific to forensic feature-comparison methods. This comprehensive analysis assesses the current state of empirical validation for forensic feature-comparison methods, identifies critical gaps, and provides structured frameworks for advancing validation practices. The focus extends across traditional pattern evidence domains including fingerprints, firearms, toolmarks, and digital evidence, where feature-comparison methods form the core of forensic evaluation [12] [13].

Current State of Empirical Validation in Forensic Feature-Comparison

Validation Frameworks and Performance Metrics

The validation of LR methods requires a structured approach with clearly defined performance characteristics and metrics. According to established guidelines, six key performance characteristics must be evaluated for any LR method intended for forensic use [12]:

- Accuracy: Measures how close the computed LRs are to ground truth values

- Discriminating Power: Assesses the method's ability to distinguish between same-source and different-source comparisons

- Calibration: Evaluates whether LRs correctly represent the strength of evidence

- Robustness: Tests method performance across varying conditions and data quality

- Coherence: Ensures internal consistency of the method's outputs

- Generalization: Verifies performance on data not used in development

Table 1: Core Performance Characteristics for LR Method Validation

| Performance Characteristic | Performance Metrics | Validation Criteria Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Cllr (Cost of log LR) | Cllr < 0.3 |

| Discriminating Power | Cllrmin, EER | Cllrmin < 0.2 |

| Calibration | Cllrcal | Cllrcal < 0.1 |

| Robustness | Performance degradation | <10% increase in Cllr |

| Coherence | Internal consistency | Method-dependent thresholds |

| Generalization | Cross-dataset performance | <15% performance decrease |

The empirical foundation for these validation metrics remains limited in many forensic domains. While DNA analysis has established robust validation frameworks, other pattern evidence disciplines struggle with insufficient data resources to properly evaluate these performance characteristics [12] [13].

Empirical Data Limitations Across Forensic Disciplines

The availability of empirical data for validation varies significantly across forensic disciplines, creating a patchwork of empirical foundations:

Table 2: Empirical Data Status Across Forensic Disciplines

| Forensic Discipline | Data Availability | Sample Size Challenges | Public Datasets |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forensic DNA | High | Minimal | Multiple available |

| Fingerprints | Moderate | Limited minutiae configurations | Limited research sets |

| Firearms & Toolmarks | Low to moderate | Extensive reference collections needed | Very limited |

| Digital forensics | Highly variable | Rapidly evolving technology | Proprietary mainly |

| Trace evidence | Very low | Heterogeneous materials | Virtually nonexistent |

The fingerprint domain illustrates both progress and persistent challenges. Research demonstrates that LR methods can be successfully applied to fingerprint evidence using Automated Fingerprint Identification System (AFIS) scores. However, the Netherlands Forensic Institute's validation study utilized simulated data for method development and real forensic data for validation, highlighting the scarcity of appropriate empirical data [13]. This two-stage approach - using simulated data for development followed by validation on forensic data - has emerged as a necessary compromise given data limitations.

Experimental Protocols for LR Method Validation

Standard Validation Methodology for Forensic Feature-Comparison

A rigorous experimental protocol for validating LR methods must encompass multiple stages from data collection to performance assessment. The workflow involves systematic processes to ensure comprehensive evaluation:

Diagram 1: LR Method Validation Workflow

The experimental protocol for fingerprint evidence validation exemplifies this approach. The process begins with collecting comparison scores from an AFIS system (e.g., Motorola BIS Printrak 9.1) treating it as a black box. The scores are generated from comparisons between fingermarks and fingerprints under two propositions: same-source (SS) and different-source (DS) [13]. This produces two distributions of scores that form the basis for LR calculation.

The core validation experiment involves:

- Dataset Specification: Separate development and validation datasets, with forensic data reserved exclusively for validation

- Score Generation: SS and DS scores generated through systematic comparisons

- LR Computation: Application of LR methods to convert scores to likelihood ratios

- Performance Assessment: Evaluation across all six performance characteristics

- Validation Decision: Pass/fail determination based on pre-established criteria

This structure ensures that validation reflects real-world conditions while maintaining methodological rigor.

Case Study: Fingerprint Evidence Validation Protocol

The Netherlands Forensic Institute's fingerprint validation study provides a concrete example of empirical validation in practice. The experimental protocol specifications include [13]:

- Data Sources: 5-12 minutiae fingermarks compared with fingerprints using AFIS comparison algorithm

- Sample Size: Sufficient comparisons to establish reliable score distributions (typically thousands of comparisons)

- Propositions:

- H1 (SS): Fingermark and fingerprint from same finger of same donor

- H2 (DS): Fingermark from random finger of unrelated donor from relevant population

- LR Computation Methods: Both feature-based and score-based approaches evaluated

- Validation Criteria: Pre-established thresholds for each performance metric

The study demonstrated that proper validation requires substantial computational resources and carefully designed experiments to assess method performance across varying conditions. The use of real forensic data for validation, coupled with simulated data for development, represents a pragmatic approach to addressing empirical data limitations.

Emerging Technologies and Their Impact on Empirical Foundations

Novel Analytical Approaches Strengthening Empirical Validation

Modern forensic technologies are gradually addressing the empirical foundation gap through advanced analytical capabilities:

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): Provides detailed genetic information from challenging samples including degraded DNA and complex mixtures, creating more robust empirical foundations for DNA evidence interpretation [14].

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning: AI algorithms can process vast datasets to identify patterns and generate quantitative measures for feature-comparison, though their validation requires particular care to ensure transparency and reliability [15].

Advanced Imaging Technologies: High-resolution 3D imaging for ballistic analysis (e.g., Forensic Bullet Comparison Visualizer) provides objective data for firearm evidence, creating empirical foundations where subjective assessment previously dominated [14].

These technologies generate quantitative data that can form the basis for empirically grounded LR methods, gradually addressing the historical lack of robust empirical foundations in many forensic disciplines.

The Research Toolkit: Essential Materials for Validation Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for LR Validation Studies

| Item/Category | Function in Validation | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Datasets | Provide ground truth for method development | NIST Standard Reference Materials, Forensic Data Exchange Format files |

| AFIS Systems | Generate comparison scores for fingerprint evidence | Motorola BIS Printrak 9.1, Next Generation Identification (NGI) System |

| Statistical Software Platforms | Implement LR computation models | R packages (e.g., forensim), Python scientific stack |

| Validation Metrics Calculators | Compute performance characteristics | FoCal Toolkit, BOSARIS Toolkit |

| Digital Evidence Platforms | Process digital forensic data | Cellebrite, FTK Imager, Open-source forensic tools |

| Ballistic Imaging Systems | Generate firearm and toolmark data | Integrated Ballistic Identification System (IBIS) |

| DNA Analysis Platforms | Support sequence data for mixture interpretation | NGS platforms, CE-based genetic analyzers |

The research toolkit continues to evolve with emerging technologies. Portable forensic technologies like mobile fingerprint scanners and portable mass spectrometers enable real-time data collection, potentially expanding empirical databases [15]. Blockchain-based solutions for maintaining chain of custody and data integrity are increasingly important for ensuring the reliability of validation data [14].

The empirical foundations for forensic feature-comparison methods remain limited but are steadily improving through structured validation frameworks, technological advancements, and increased data sharing. The validation guideline for LR methods provides a essential roadmap for assessing method performance across critical characteristics including accuracy, discrimination, calibration, robustness, coherence, and generalization [12].

Addressing the empirical deficit requires concerted effort across multiple fronts: expanding shared datasets of forensic relevance, developing standardized validation protocols specific to each forensic discipline, increasing transparency in validation reporting, and fostering collaboration between research institutions and operational laboratories. The continued development and validation of empirically grounded LR methods represents the most promising path toward strengthening the scientific foundation of forensic feature-comparison evidence.

Within the framework of validating likelihood ratio (LR) methods for forensic evidence research, a critical yet often underexplored component is human comprehension. The LR quantifies the strength of forensic evidence by comparing the probability of the evidence under two competing propositions, typically the prosecution and defense hypotheses [16]. While extensive research focuses on the computational robustness and statistical validity of LR systems, understanding how these numerical values are interpreted by legal decision-makers—including judges, jurors, and attorneys—is paramount for the practical efficacy of the justice system. This review synthesizes empirical studies on the comprehension challenges associated with LR presentations, objectively comparing the effectiveness of different presentation formats and analyzing the experimental data that underpin these findings.

Comprehensive Review of LR Comprehension Studies

Core Comprehension Challenges and the CASOC Framework

A systematic review of the empirical literature reveals that existing research often investigates the understanding of expressions of strength of evidence broadly, rather than focusing specifically on likelihood ratios [8]. This presents a significant gap. To structure the analysis of comprehension, studies are frequently evaluated against the CASOC indicators of comprehension: sensitivity, orthodoxy, and coherence [8].

- Sensitivity refers to the ability of an individual to perceive differences in the strength of evidence as the LR value changes.

- Orthodoxy measures whether the interpretation of the LR aligns with its intended statistical meaning and the principles of Bayesian reasoning.

- Coherence assesses the logical consistency of an individual's interpretations across different but related evidential scenarios.

A primary finding across the literature is that laypersons often struggle with the probabilistic intuition required to correctly interpret LR values, frequently misinterpreting the LR as the probability of one of the propositions being true, rather than the strength of the evidence given the propositions [8].

Comparative Analysis of LR Presentation Formats

Researchers have explored various formats to present LRs, aiming to enhance comprehension. The table below summarizes the primary formats studied and their associated comprehension challenges based on empirical findings.

Table 1: Comparison of Likelihood Ratio Presentation Formats and Comprehension Challenges

| Presentation Format | Description | Key Comprehension Challenges | Empirical Findings Summary |

|---|---|---|---|

| Numerical Likelihood Ratios [8] | Presenting the LR as a direct numerical value (e.g., LR = 10,000). | Laypersons find very large or very small numbers difficult to contextualize and weigh appropriately. Can lead to poor sensitivity and a lack of orthodoxy. | Often misunderstood without statistical training; however, provides the most unadulterated quantitative information. |

| Random Match Probabilities (RMPs) [8] | Presenting the probability of a random match (e.g., 1 in 10,000). | Prone to the "prosecutor's fallacy," where the RMP is mistakenly interpreted as the probability that the defendant is innocent. This is a major failure in orthodoxy. | While sometimes easier to grasp initially, this format is associated with a higher rate of logical fallacies and misinterpretations. |

| Verbal Strength-of-Support Statements [8] | Using qualitative phrases like "strong support" or "moderate support" for the prosecution's proposition. | Lacks precision and can be interpreted subjectively, leading to low sensitivity and inconsistency (incoherence) between different users and cases. | Provides a simple, accessible summary but sacrifices quantitative nuance and can obscure the true strength of evidence. |

| Log Likelihood Ratio Cost (Cllr) [17] | A performance metric for (semi-)automated LR systems, where Cllr = 0 indicates perfection and Cllr = 1 an uninformative system. | Not a direct presentation format for laypersons, but its use in validation highlights system reliability. Comprehension challenges relate to its interpretation by researchers and practitioners. | Values vary substantially between forensic analyses and datasets, making it difficult to define a universally "good" Cllr, complicating cross-study comparisons [17]. |

A critical observation from the literature is that none of the reviewed studies specifically tested the comprehension of verbal likelihood ratios (e.g., directly translating "LR=1000" to "this evidence provides very strong support"), indicating a notable gap for future research [8].

Detailed Experimental Protocols in LR Comprehension Research

To objectively assess the performance of different LR presentation formats, researchers employ controlled experimental designs. The following workflow details a common methodology derived from the reviewed literature.

Diagram 1: Experimental protocol for LR comprehension studies.

Protocol Breakdown

- Participant Recruitment: Studies typically recruit participants who represent the target audience of legal decision-makers, most often laypersons with no specialized training in statistics or forensic science [8].

- Randomized Group Assignment: Participants are randomly assigned to different experimental groups. Each group is exposed to the same underlying case information and LR value but presented in a different format (e.g., one group sees a numerical LR, another sees a verbal equivalent) [8].

- Training/Briefing: Some studies provide minimal background on the meaning of the evidence, while others may offer a basic explanation of the assigned presentation format to simulate real-world instruction from an expert witness.

- Exposure to LR Format: Participants are presented with the forensic evidence within a simplified case narrative. The key manipulated variable is the format in which the LR is communicated (see Table 1).

- Comprehension Assessment: Understanding is measured using questionnaires and tasks designed to probe the CASOC indicators:

- Sensitivity: Participants might be asked to compare the strength of evidence between two cases with different LRs.

- Orthodoxy: Questions are designed to identify common fallacies, such as the prosecutor's fallacy.

- Coherence: Participants might be asked to provide a probability or estimate of guilt, allowing researchers to check for logical consistency with the presented LR.

- Data Analysis & Validation: Responses are quantitatively and qualitatively analyzed. Statistical tests (e.g., ANOVA) are used to compare performance (accuracy in interpretation, resistance to fallacies) across the different presentation format groups. This validates which format, under the tested conditions, best mitigates comprehension challenges.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The development and validation of LR systems, as well as the study of their comprehension, rely on a suite of specialized tools and materials. The following table details key "research reagents" essential for this field.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Forensic LR Research

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function in LR Research & Validation |

|---|---|

| Benchmark Datasets [17] | Publicly available, standardized datasets (e.g., from the 1000 Genomes Project) that allow for the direct comparison of different LR algorithms and systems, addressing a critical need in the field. |

| Specialized SNP Panels [18] | Genotyping arrays, such as the validated 9000-SNP panel for East Asian populations, provide the high-resolution data required for inferring distant relatives and computing robust LRs in forensic genetics. |

| Validation Guidelines (SWGDAM) [18] | Established protocols from bodies like the Scientific Working Group on DNA Analysis Methods that define the required experiments (sensitivity, specificity, reproducibility) to validate a new forensic LR method. |

| Performance Metrics (Cllr) [17] | Scalar metrics like the log likelihood ratio cost are used to evaluate the performance of (semi-)automated LR systems, penalizing misleading LRs and providing a measure of system reliability. |

| Statistical Software & LR Algorithms [18] [16] | Custom or commercial algorithms for calculating LRs from complex data, such as pedigree genotyping data or Sensor Pattern Noise (SPN) from digital images. |

The empirical review conclusively demonstrates that the "best" way to present likelihood ratios to maximize understandability remains an unresolved question [8]. Numerical formats, while precise, are cognitively challenging. Verbal statements improve accessibility but at the cost of precision and consistency. Alternative formats like RMPs, though intuitive, introduce significant logical fallacies. The consistent finding is that all common presentation formats face substantial comprehension challenges related to the CASOC indicators. Future research must not only refine these formats but also explore novel ones, such as verbal likelihood ratios, and do so using robust, methodologically sound experiments with public benchmark datasets to enable meaningful progress in the field [8] [17].

From Theory to Practice: Implementing LR Methods in Research and Safety Monitoring

Likelihood Ratio Tests (LRTs) for Drug Safety Signal Detection in Multiple Studies

In the domain of pharmacovigilance and post-market drug safety surveillance, the accurate detection of adverse event (AE) signals from multiple, heterogeneous clinical datasets presents a significant statistical challenge. The integration of results from various studies is crucial for a comprehensive safety evaluation of a drug. This guide objectively compares the performance of several Likelihood-Ratio-Test (LRT) based methods specifically designed for this task, framing the discussion within the broader thesis of validating likelihood ratio methods, a cornerstone of modern forensic evidence interpretation [8] [19]. Just as forensic science relies on calibrated likelihood ratios to evaluate the strength of evidence for source attribution [20], the pharmaceutical industry can employ these statistical frameworks to quantify the evidence for drug-safety hypotheses. We summarize experimental data and provide detailed protocols to help researchers select and implement the most appropriate LRT method for their specific safety monitoring objectives.

Methodological Comparison of LRT Approaches

The application of LRTs in drug safety signal detection involves testing hypotheses about the association between a drug and an adverse event across multiple studies. The core likelihood ratio compares the probability of the observed data under two competing hypotheses, typically where the alternative hypothesis (H1) allows for a drug-AE association and the null hypothesis (H0) does not [21] [22].

Core LRT Methods for Multi-Dataset Analysis

Three primary LRT-based methods have been proposed for integrating information from multiple clinical datasets [21].

Simple Pooled LRT: This method aggregates individual patient-level data from all available studies into a single, combined dataset. A standard likelihood ratio test is then performed on this pooled dataset. Its main advantage is simplicity, but it assumes homogeneity across all studies, which is often unrealistic in real-world settings and can lead to biased results if this assumption is violated.

Weighted LRT: This approach incorporates total drug exposure information from each study. By weighting the contribution of each study by its sample size or exposure level, the method acknowledges that studies with larger sample sizes should provide more reliable estimates and thus exert a greater influence on the combined result. This can improve the efficiency and accuracy of signal detection.

Meta-Analytic LRT (Advanced): While not explicitly named in the search results, a more complex variation involves performing a meta-analysis of likelihood ratios or their components from each study. This method does not pool raw data but instead combines the statistical evidence from each study's independent analysis, potentially using a random-effects model to account for between-study heterogeneity.

The following workflow outlines the generic procedural steps for applying these methods.

Performance Comparison: Power and Type I Error

Simulation studies evaluating these LRT methods have provided quantitative performance data, particularly under varying degrees of heterogeneity across studies [21]. The table below summarizes key findings regarding their statistical power and ability to control false positives (Type I error).

Table 1: Comparative Performance of LRT Methods for Drug Safety Signal Detection

| LRT Method | Description | Power (Ability to detect true signals) | Type I Error Control (False positive rate) | Robustness to Heterogeneity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simple Pooled LRT | Pools raw data from all studies into a single dataset for analysis. | High when studies are homogeneous. | Can be inflated if study heterogeneity is present. | Low |

| Weighted LRT | Weights contribution of each study by sample size or exposure. | Generally high, and more efficient than simple pooling. | Maintains good control when weighting is appropriate. | Moderate |

| Meta-Analytic LRT | Combines statistical evidence from separate study analyses. | Good, especially with random-effects models. | Good control when properly specified. | High |

The choice of method involves a trade-off between simplicity and robustness. The Weighted LRT often represents a practical compromise, offering improved performance over the simple pooled approach without the complexity of a full meta-analytic model [21].

Experimental Protocols and Validation

Validating any statistical method for signal detection requires rigorous testing against both simulated and real-world data to establish its operating characteristics.

Protocol for Simulation Studies

Simulation studies are essential for evaluating the statistical properties (power and Type I error) of the LRT methods under controlled conditions [21].

- Data Generation: Simulate multiple clinical datasets. The number of studies (

K), sample sizes per study (n_i), and underlying true incidence rates of AEs should be pre-defined. - Introduce Heterogeneity: Vary the baseline AE rates and/or the strength of the drug-AE association (effect size) across the simulated studies to mimic real-world variability.

- Apply LRT Methods: Implement the Simple Pooled, Weighted, and Meta-Analytic LRT methods on the simulated datasets.

- Evaluate Performance:

- Type I Error: Under the null hypothesis (no true drug-AE association), run thousands of simulations. The proportion of times the LRT incorrectly rejects the null hypothesis (a false positive) is the empirical Type I error rate. This should be close to the nominal level (e.g., 0.05).

- Power: Under the alternative hypothesis (a true, specified drug-AE association), run thousands of simulations. The proportion of times the LRT correctly rejects the null hypothesis is the empirical power.

Application to Real-World Data: Case Studies

The following case studies demonstrate the application of LRT methods to real drug safety data [21].

Table 2: Case Study Applications of LRT Methods

| Drug Case | Data Source | Number of Studies | Key Finding from LRT Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs) | Analysis of concomitant use in patients with osteoporosis. | 6 | The LRT methods were applied to identify signals of adverse events associated with the concomitant use pattern, demonstrating practical utility. |

| Lipiodol (contrast agent) | Evaluation of the drug's overall safety profile. | 13 | The methods successfully processed a larger number of studies to evaluate signals for multiple associated adverse events. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents and Materials

Implementing LRT methods for drug safety surveillance requires a suite of statistical and computational tools.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for LRT Implementation

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Description | Application in LRT Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software (R, Python, SAS) | Provides the computational environment for data manipulation, model fitting, and statistical testing. | Essential for coding the likelihood functions, performing maximization, and calculating the test statistic. |

| Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) | An iterative optimization algorithm used to find the parameter values that make the observed data most probable. | Core to all LRT methods; used to estimate parameters under both H0 and H1 hypotheses. |

| Chi-Square Distribution Table | A reference for critical values of the chi-square distribution, which is the asymptotic distribution of the LRT statistic under H0. | Used to determine the statistical significance (p-value) of the observed test statistic. |

| Pharmacovigilance Database | A structured database (e.g., FDA Adverse Event Reporting System) containing case reports of drug-AE pairs. | The primary source of observational data for analysis. Requires careful pre-processing before LRT application. |

Advanced Concepts and Workflow

For researchers seeking a deeper understanding, the signed log-likelihood ratio test (SLRT) offers enhanced performance, particularly for small-sample inference as demonstrated in reliability engineering [23] [24]. Simulation studies show the SLRT maintains Type I error rates within acceptable ranges (e.g., 0.04-0.06 at a 0.05 significance level) and achieves higher statistical power compared to tests based solely on asymptotic normality of estimators, especially with small samples (n = 10, 15) [24].

The following diagram illustrates the complete analytical workflow for LRT-based drug safety signal detection.

Likelihood Ratio Tests provide a statistically rigorous and flexible framework for detecting drug safety signals from multiple clinical datasets. The Weighted LRT method stands out for its balance of performance and practicality, effectively incorporating exposure information to enhance signal detection. As in forensic science, where the precise calibration of likelihood ratios is critical for valid evidence interpretation [19] [20], the future of pharmacovigilance lies in the continued refinement and validation of these methods. This ensures that the detection of adverse events is both sensitive to true risks and robust to false alarms, ultimately strengthening post-market drug safety monitoring.

The integration of pre-test probability with diagnostic likelihood ratios (LRs) through Bayes' Theorem represents a foundational methodology for reasoning under uncertainty across multiple scientific disciplines. This probabilistic framework provides a structured mechanism for updating belief in a hypothesis—whether the presence of a disease or the source of forensic evidence—as new diagnostic information becomes available [25] [26]. The core strength of this approach lies in its formal recognition of context, mathematically acknowledging that the value of any test result depends critically on what was already known or believed before the test was performed [27].

In both clinical and forensic settings, the likelihood ratio serves as the crucial bridge between pre-test and post-test probabilities, quantifying how much a piece of evidence—be it a laboratory test result or a biometric similarity score—should shift our initial assessment [3]. This article objectively compares the performance of different methodological approaches for applying Bayes' Theorem, with a specific focus on validation techniques relevant to forensic evidence research. The validation of these probabilistic methods is paramount, as it ensures that the reported strength of evidence reliably reflects ground truth, enabling researchers, scientists, and legal professionals to make informed decisions based on statistically sound interpretations of data.

Theoretical Foundations: Pre-test Probability, LRs, and Bayes' Theorem

Core Definitions and Calculations

The Bayesian diagnostic framework rests on three interconnected components: pre-test probability, likelihood ratios, and post-test probability.

Pre-test Probability: This is the estimated probability that a condition is true (e.g., a patient has a disease, or a piece of evidence originates from a specific source) before the new test result is known [25] [27]. In a population, this is equivalent to the prevalence of the condition, but for an individual, it is modified by specific risk factors, symptoms, or other case-specific information [26]. For instance, the pre-test probability of appendicitis is much higher in a patient presenting to the emergency department with right lower quadrant tenderness than in the general population [25].

Likelihood Ratios (LRs): The LR quantifies the diagnostic power of a specific test result. It is the ratio of the probability of observing a given result if the condition is true to the probability of observing that same result if the condition is false [3]. It is calculated from a test's sensitivity and specificity.

- Positive Likelihood Ratio (LR+): Indicates how much the odds of the condition increase when a test is positive. It is calculated as LR+ = Sensitivity / (1 - Specificity) [25] [3].

- Negative Likelihood Ratio (LR-): Indicates how much the odds of the condition decrease when a test is negative. It is calculated as LR- = (1 - Sensitivity) / Specificity [25] [3]. An LR further from 1 (either much greater than 1 or much closer to 0) indicates a more informative test [25].

Bayes' Theorem: The theorem provides the mathematical rule for updating the pre-test probability using the LR to obtain the post-test probability. The most computationally straightforward method uses odds rather than probabilities directly [25] [26]:

- Convert Pre-test Probability to Pre-test Odds:

Odds = Probability / (1 - Probability) - Multiply by the LR to get Post-test Odds:

Post-test Odds = Pre-test Odds × LR - Convert Post-test Odds back to Post-test Probability:

Probability = Odds / (1 + Odds)

- Convert Pre-test Probability to Pre-test Odds:

The Bayesian Inference Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow of integrating pre-test probability with a test result using Bayes' Theorem to arrive at a post-test probability.

Comparative Analysis of LR Validation Methodologies

Validation of likelihood ratio methods is critical to ensure their reliability in both clinical diagnostics and forensic science. The table below summarizes the core principles, typical applications, and key challenges of three distinct methodological approaches.

Table 1: Comparison of Likelihood Ratio Validation Methodologies

| Methodological Approach | Core Principle | Typical Application Context | Key Experimental Output | Primary Validation Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Clinical Validation | Uses known sensitivity/specificity from studies comparing diseased vs. non-diseased cohorts [26] [27]. | Medical diagnostic tests (e.g., exercise ECG for coronary artery disease) [26]. | Single, overall LR+ and LR- for the test [3]. | Assumes fixed performance; ignores variability in sample/evidence quality. |

| Score-Based Likelihood Ratios (SLR) | Converts continuous similarity scores from automated systems into an LR using score distributions [28]. | Biometric recognition (e.g., facial images, speaker comparison) [28]. | Calibration curve mapping similarity scores to LRs. | Requires large, representative reference databases to model score distributions accurately. |

| Feature-Based Calibration | Constructs a custom calibration population for each case based on specific features (e.g., image quality, demographics) [28]. | Forensic face comparison where evidence quality is highly variable [28]. | Case-specific LR estimates tailored to the features of the evidence. | Computationally intensive; requires an extremely large and diverse background dataset. |

Experimental Protocols for Forensic LR Validation

A prominent area of methodological development is the validation of LRs for forensic facial image comparison, which highlights the trade-offs between different approaches.

Protocol for Score-Based Likelihood Ratios (SLR) with Quality Assessment

This protocol, building on the work of Ruifrok et al. and extended with open-source tools, provides a practical method for incorporating image quality into LR calculation [28].

- Image Acquisition and Curation: A database of facial images is compiled. For validation purposes, the identity of the person in each image (the "ground truth") must be known.

- Image Quality Scoring: Each image is processed using the Open-Source Facial Image Quality (OFIQ) library to calculate a Universal Quality Score (UQS). The UQS is a composite metric based on attributes like lighting uniformity, head position, and sharpness [28].

- Stratification by Quality: Images are grouped into intervals based on their UQS (e.g., 0-2, 3-5, 6-8, 9-10) to create distinct quality cohorts.

- Similarity Score Generation: For each quality stratum, a facial recognition system (e.g., using the Neoface algorithm) is used to generate similarity scores for many pairs of images. This includes:

- Within-Source Variability (WSV) scores: Similarity scores from different images of the same person.

- Between-Source Variability (BSV) scores: Similarity scores from images of different people [28].

- SLR Calculation: For a given quality stratum, the distributions of WSV and BSV scores are modeled. The SLR for a new case with a specific similarity score (S) is calculated as the ratio of the probability densities:

SLR = pdf(WSV | S) / pdf(BSV | S)[28]. - Validation: The method is validated by testing its performance on a separate dataset and ensuring that the calculated LRs are accurate and do not exceed pre-determined maximum error limits.

Protocol for Feature-Based Calibration

This alternative protocol aims for higher forensic validity by tailoring the background population more precisely to the case at hand [28].

- Case Feature Extraction: The trace image (e.g., from CCTV) is analyzed to define a set of relevant features, which may include the OFIQ score, but also demographic factors (sex, ethnicity, age), presence of facial hair, glasses, or occlusions.

- Dynamic Population Selection: For the specific case, a custom calibration population is constructed by selecting images from a master database that match the defined feature profile of the trace image.

- Score Distribution Modeling: Similarity score distributions (WSV and BSV) are generated only from this feature-matched population.

- LR Calculation: The LR is calculated using the feature-specific score distributions, making it a more tailored estimate of the evidence's strength for that particular case.

Quantitative Data Interpretation and Decision Thresholds

The ultimate value of a diagnostic test or a piece of forensic evidence lies in its ability to change the probability of a hypothesis sufficiently to cross a decision threshold.

Impact of LR Values on Post-Test Probability

The following reference table provides approximate changes in probability for a range of LR values, which is invaluable for intuitive interpretation [3].

Table 2: Effect of Likelihood Ratio Values on Post-Test Probability

| Likelihood Ratio (LR) Value | Approximate Change in Probability | Interpretive Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| 0.1 | -45% | Large decrease |

| 0.2 | -30% | Moderate decrease |

| 0.5 | -15% | Slight decrease |

| 1 | 0% | No change (test is uninformative) |

| 2 | +15% | Slight increase |

| 5 | +30% | Moderate increase |

| 10 | +45% | Large increase |

Note: These estimates are accurate to within 10% for pre-test probabilities between 10% and 90% [3].

The Threshold Model for Test and Treatment Decisions

A critical application of this framework is the "threshold model" for clinical decision-making. This model posits that one should only order a diagnostic test if its result could potentially change patient management. This occurs when the pre-test probability falls between a "test threshold" and a "treatment threshold." If the pre-test probability is so low that even a positive test would not raise it above the treatment threshold, the test is not indicated. Conversely, if the pre-test probability is so high that treatment would be initiated regardless of the test result, the test is similarly unnecessary [26]. The same logic applies in forensic contexts, where the pre-test probability (initial suspicion) and the strength of evidence (LR) must be sufficient to meet a legal standard of proof.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The experimental protocols for developing and validating LR methods, particularly in forensic biometrics, rely on a suite of specialized software tools and datasets.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for LR Validation Experiments

| Reagent / Tool | Type | Primary Function in LR Research |

|---|---|---|

| Open-Source Facial Image Quality (OFIQ) Library | Software Library | Provides standardized, automated assessment of facial image quality based on multiple attributes (lighting, pose, sharpness) [28]. |

| Neoface Algorithm | Biometric Software | Generates the core similarity scores between pairs of facial images, which serve as the raw data for Score-based LR calculation [28]. |

| Confusion Score Database | Curated Dataset | A dataset of images with conditions matching the trace image, used to quantify how easily a trace can be confused with different-source images in some methodologies [28]. |

| FISWG Facial Feature List | Standardized Taxonomy | Provides a structured checklist and terminology for morphological analysis in forensic facial comparison, supporting subjective expert assessment [28]. |

| Bayesian Statistical Software (R, MATLAB) | Analysis Platform | Used for complex statistical modeling, including kernel density estimation of score distributions and calculation of calibrated LRs [29] [28]. |

The objective comparison of methodologies for integrating pre-test probability with diagnostic LRs reveals a spectrum of approaches, each with distinct advantages and operational challenges. The traditional clinical model provides a foundational framework but lacks the granularity needed for complex forensic evidence. The emerging SLR methods, particularly when enhanced with open-source quality assessment tools, offer a robust and practical balance between computational feasibility and empirical validity. For the highest level of forensic validity in cases with highly variable evidence quality, feature-based calibration represents the current state-of-the-art, despite its significant resource demands. For researchers and scientists, the selection of a validation methodology must be guided by the specific context, the required level of precision, and the available resources. The ongoing validation of these probabilistic methods remains crucial for upholding the integrity of evidence interpretation in both medicine and law.

Likelihood Ratio Test (LRT) methodologies serve as fundamental tools for statistical inference across diverse scientific domains, including forensic evidence research and drug development. These methods enable researchers to compare the relative support for competing hypotheses given observed data. Within the context of forensic evidence validation, the LRT framework provides the logically correct structure for interpreting forensic findings [30]. This guide objectively compares the performance of three principal LRT-based approaches—Simple Pooled, Weighted, and novel Pseudo-LRT methods—by synthesizing experimental data from validation studies and highlighting their respective advantages, limitations, and optimal use cases.

The critical importance of method validation in forensic science cannot be overstated, as it ensures that techniques are technically sound and produce robust, defensible analytical results [31]. Similarly, in pharmaceutical research, controlling Type I error and maintaining statistical power are paramount when evaluating treatment effects in clinical trials [32]. By examining the performance characteristics of different LRT methodologies within this validation framework, researchers can make informed selections appropriate for their specific analytical requirements.

Simple Pooled Methods

Simple pooled methods represent the most straightforward approach to likelihood ratio testing, operating under the assumption that all data originate from a homogeneous population. In the context of Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium testing for genetic association studies, the pooled χ² test combines case and control samples to estimate the Hardy-Weinberg disequilibrium coefficient [33]. This method demonstrates high statistical power when its underlying assumptions are met, particularly when the candidate marker is independent of the disease status. However, this approach becomes invalid when population stratification exists or when the marker exhibits association with the disease, as the genotype distributions in case-control samples no longer represent the target population [33].

In forensic science, a parallel approach involves pooling response data across multiple examiners and test trials to calculate likelihood ratios based on categorical conclusions [30]. While computationally efficient and straightforward to implement, this method fails to account for examiner-specific performance variations or differences in casework conditions, potentially leading to misleading results in actual forensic practice [30].

Weighted Methods

Weighted approaches incorporate statistical adjustments to address heteroscedasticity and improve variance estimation. In single-cell RNA-seq analysis, methods such as voomWithQualityWeights and voomByGroup assign quality weights to samples or groups to account for unequal variability across experimental conditions [34]. These techniques adjust variance estimates at either the sample or group level, effectively modeling heteroscedasticity frequently observed in pseudo-bulk datasets [34].

Similarly, in pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic modeling, model-averaging techniques such as Model-Averaging across Drug models (MAD) and Individual Model Averaging (IMA) weight outcomes from pre-selected candidate models according to goodness-of-fit metrics like Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) [32]. This approach mitigates selection bias and accounts for model structure uncertainty, potentially offering more robust inference compared to methods relying on a single selected model [32].

Novel Pseudo-LRT Methods

Novel Pseudo-LRT methods represent advanced approaches that adapt traditional likelihood ratio testing to address specific methodological challenges. The shrinkage test for assessing Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium exemplifies this category, combining elements of both pooled and generalized χ² tests through a weighted average [33]. This hybrid approach converges to the efficient pooled χ² test when the genetic marker is independent of disease status, while maintaining the validity of the generalized χ² test when associations exist [33].

In longitudinal data analysis, the combined Likelihood Ratio Test (cLRT) and randomized cLRT (rcLRT) incorporate alternative cutoff values and randomization procedures to control Type I error inflation resulting from multiple testing and model misspecification [32]. These methods demonstrate particular utility when analyzing balanced two-armed treatment studies with potential placebo model misspecification [32].

Table 1: Core Characteristics of LRT Method Categories

| Method Category | Key Characteristics | Primary Advantages | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simple Pooled | Assumes population homogeneity; computationally efficient | High power when assumptions are met; straightforward implementation | Initial quality control of genotyping [33]; Preliminary data screening |

| Weighted | Incorporates quality weights; accounts for heteroscedasticity | Handles unequal group variances; reduces selection bias | RNA-seq analysis with heteroscedastic groups [34]; Model averaging in pharmacometrics [32] |

| Novel Pseudo-LRT | Hybrid approaches; adaptive test statistics | Maintains validity across conditions; controls Type I error | HWE testing with associated markers [33]; Longitudinal treatment effect assessment [32] |

Experimental Comparison

Study Designs and Protocols

To evaluate the performance characteristics of different LRT methodologies, researchers have employed various experimental designs across multiple disciplines. In genetic epidemiology, simulation studies comparing HWE testing approaches generate genotype counts for cases and controls under various disease prevalence scenarios and genetic association models [33]. These simulations typically assume a bi-allelic marker with alleles A and a, with genotype frequencies following Hardy-Weinberg proportions in the general population [33]. The genetic relative risks (λ₁ and λ₂) are varied to represent different genetic models (recessive, additive, dominant) and association strengths.

In pharmacometric applications, researchers often utilize real natural history data—such as Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale-cognitive (ADAS-cog) scores from the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database—to assess Type I error rates by randomly assigning subjects to placebo and treatment groups despite all following natural disease progression [32]. To evaluate power and accuracy, various treatment effect functions (e.g., offset, time-linear) are added to the treated arm's data, with different typical effect sizes and inter-individual variability [32].

For forensic science validation, "black-box studies" present examiners with questioned-source items and known-source items in test trials, collecting categorical responses from ordinal scales (e.g., "Identification," "Inconclusive," "Elimination") [30]. These response data then train statistical models to convert categorical conclusions into likelihood ratios, with performance assessed through metrics like log-likelihood-ratio cost (Cₗₗᵣ) [30].

Performance Metrics and Quantitative Results

The performance of LRT methodologies is typically evaluated using standardized metrics, including Type I error rate, statistical power, root mean squared error (RMSE) for parameter estimates, and in forensic applications, the log-likelihood-ratio cost (Cₗₗᵣ).

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison Across Method Types

| Method | Type I Error Control | Power Characteristics | Accuracy (RMSE) | Conditions for Optimal Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simple Pooled χ² test | Inflated when associations exist [33] | High when marker independent of disease [33] | Not reported | Random population samples; no population stratification |

| Control-only χ² test | Inflated for moderate/high disease prevalence [33] | Reduced due to discarded case information [33] | Not reported | Rare diseases with low prevalence |

| Shrinkage Test | Maintains validity across association strengths [33] | Higher than LRT for independent/weakly associated markers [33] | Not reported | Case-control studies with unknown disease association |

| IMA | Controlled Type I error [32] | Reasonable across scenarios, except low typical treatment effect [32] | Good accuracy in treatment effect estimation [32] | Model misspecification present; balanced two-armed designs |