Validating Forensic Inference Systems: A Framework for Ensuring Reliability with Relevant Data

This article provides a comprehensive framework for the empirical validation of forensic inference systems, emphasizing the critical role of relevant data.

Validating Forensic Inference Systems: A Framework for Ensuring Reliability with Relevant Data

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for the empirical validation of forensic inference systems, emphasizing the critical role of relevant data. It explores foundational scientific principles, details methodological applications across diverse forensic disciplines, addresses common challenges in optimization, and establishes rigorous validation and comparative standards. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the content synthesizes current best practices and guidelines to ensure that forensic methodologies are transparent, reproducible, and legally defensible, thereby strengthening the reliability of evidence in research and judicial processes.

The Scientific Pillars of Forensic Validation

Defining Empirical Validation in Forensic Science

Empirical validation in forensic science is the process of rigorously testing a forensic method or system under controlled conditions that replicate real-world casework to demonstrate its reliability, accuracy, and limitations. The fundamental purpose is to provide scientifically defensible evidence that a technique produces trustworthy results before it is deployed in actual investigations or courtroom proceedings. This process has become increasingly crucial as forensic science faces heightened scrutiny regarding the validity and reliability of its practices. Proper validation ensures that methods are transparent, reproducible, and intrinsically resistant to cognitive bias, thereby supporting the administration of justice with robust scientific evidence [1] [2].

Within the broader thesis on validation frameworks for forensic inference systems, empirical validation serves as the critical bridge between theoretical development and practical application. It moves a method from being merely plausible to being empirically demonstrated as fit-for-purpose. The contemporary forensic science landscape increasingly recognizes that without proper validation, forensic evidence may mislead investigators and the trier-of-fact, potentially resulting in serious miscarriages of justice [1] [3]. This article examines the core requirements, experimental approaches, and practical implementations of empirical validation across different forensic disciplines.

Core Requirements for Empirical Validation

Foundational Principles

Two fundamental requirements form the cornerstone of empirically valid forensic methods according to recent research. First, validation must replicate the specific conditions of the case under investigation. Second, it must utilize data that is relevant to that case [1]. These requirements ensure that validation studies accurately reflect the challenges and variables present in actual forensic casework rather than ideal laboratory conditions.

The International Organization for Standardization has codified requirements for forensic science processes in ISO 21043. This standard provides comprehensive requirements and recommendations designed to ensure quality throughout the forensic process, including vocabulary, recovery of items, analysis, interpretation, and reporting [2]. Conformity with such standards helps ensure that validation practices meet internationally recognized benchmarks for scientific rigor.

The Likelihood-Ratio Framework

A critical development in modern forensic validation has been the adoption of the likelihood-ratio (LR) framework for evaluating evidence. The LR provides a quantitative statement of evidence strength, calculated as the probability of the evidence given the prosecution hypothesis divided by the probability of the same evidence given the defense hypothesis [1]:

[ LR = \frac{p(E|Hp)}{p(E|Hd)} ]

This framework forces explicit consideration of both similarity (how similar the samples are) and typicality (how distinctive this similarity is) when evaluating forensic evidence. The logically and legally correct application of this framework requires empirical validation to determine actual performance metrics such as false positive and false negative rates [1] [3].

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Case Study: Forensic Text Comparison

Recent research in forensic text comparison (FTC) illustrates the critical importance of proper validation design. One study demonstrated how overlooking topic mismatch between questioned and known documents can significantly mislead results. Researchers performed two sets of simulated experiments: one fulfilling validation requirements by using relevant data and replicating case conditions, and another overlooking these requirements [1].

The experimental protocol employed a Dirichlet-multinomial model to calculate likelihood ratios, followed by logistic-regression calibration. The derived LRs were assessed using the log-likelihood-ratio cost and visualized through Tippett plots. Results clearly showed that only experiments satisfying both validation requirements (relevant data and replicated case conditions) produced forensically reliable outcomes, highlighting the necessity of proper validation design [1].

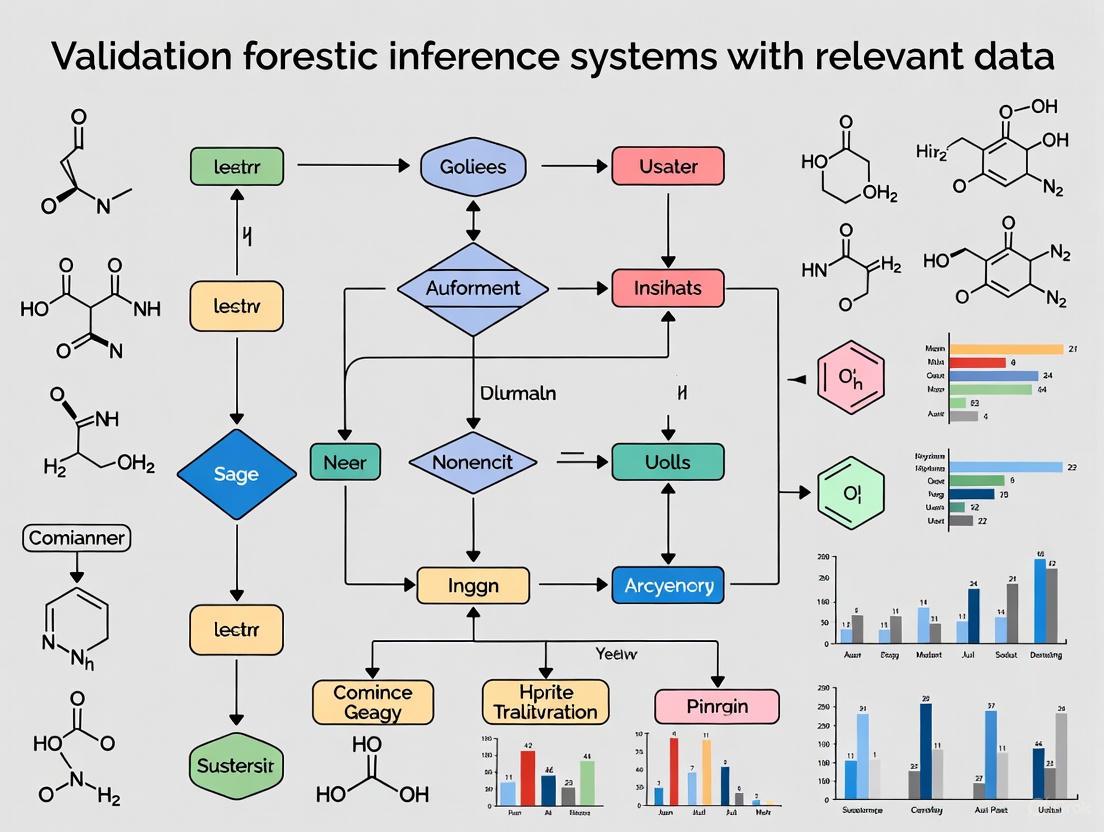

Figure 1: Forensic Text Comparison Validation Workflow

Molecular Forensic Validation

In DNA-based forensic methods, validation follows stringent developmental guidelines. A recent study establishing a DIP panel for forensic ancestry inference and personal identification demonstrates comprehensive validation protocols. The methodology included population genetic parameters, principal component analysis (PCA), STRUCTURE analysis, and phylogenetic tree construction to evaluate ancestry inference capacity [4].

Developmental validation followed verification guidelines recommended by the Scientific Working Group on DNA Analysis Methods and included assessments of PCR conditions, sensitivity, species specificity, stability, mixture analysis, reproducibility, case sample studies, and analysis of degraded samples. This multifaceted approach ensured the 60-marker panel was suitable for forensic testing, particularly with challenging samples like degraded DNA [4].

Quantitative Comparison of Validation Data

Performance Metrics Across Disciplines

Table 1: Comparative Validation Metrics Across Forensic Disciplines

| Forensic Discipline | Validation Metrics | Reported Values | Methodology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forensic Text Comparison [1] | Log-likelihood-ratio cost (Cllr) | Significantly better when validation requirements met | Dirichlet-multinomial model with logistic regression calibration |

| DIP Panel for Ancestry [4] | Combined probability of discrimination | 0.999999999999 | 56 autosomal DIPs, 3 Y-chromosome DIPs, Amelogenin |

| DIP Panel for Ancestry [4] | Cumulative probability of paternity exclusion | 0.9937 | Population genetic analysis across East Asian populations |

| 16plex SNP Assay [5] | Ancestry inference accuracy | High accuracy across populations | Capillary electrophoresis, microarray, MPS platforms |

Error Rate Considerations

A critical aspect of empirical validation is the comprehensive assessment of error rates, including both false positives and false negatives. Recent research highlights that many forensic validity studies report only false positive rates while neglecting false negative rates, creating an incomplete assessment of method accuracy [3]. This asymmetry is particularly problematic in cases involving a closed pool of suspects, where eliminations based on class characteristics can function as de facto identifications despite potentially high false negative rates.

The overlooked risk of false negative rates in forensic firearm comparisons illustrates this concern. While recent reforms have focused on reducing false positives, eliminations based on intuitive judgments receive little empirical scrutiny despite their potential to exclude true sources. Comprehensive validation must therefore include balanced reporting of both error types to properly inform the trier-of-fact about method limitations [3].

Implementation in Forensic Practice

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Resources for Forensic Validation

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function in Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Markers | 60-DIP Panel [4], 16plex SNP Assay [5] | Ancestry inference and personal identification from challenging samples |

| Statistical Tools | Likelihood-Ratio Framework [1], Cllr, Tippett Plots [1] | Quantitative evidence evaluation and method performance assessment |

| Reference Databases | NIST Ballistics Toolmark Database [6], STRBase [7], YHRD [7] | Reference data for comparison and population statistics |

| Standardized Protocols | ISO 21043 [2], SWGDAM Guidelines [4] | Quality assurance and methodological standardization |

Data Management Considerations

Effective validation requires robust data management practices. The FAIR principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) provide guidance for data handling in forensic research [8]. Proper data sharing and long-term storage remain challenging but can be facilitated by giving data structure, using suitable labels, and including descriptors collated into metadata prior to deposition in repositories with persistent identifiers. This systematic approach strengthens research quality and integrity while providing greater transparency to published materials [8].

Numerous open-source datasets and databases are available to support forensic validation, including those offered by CSAFE and other organizations [6]. These resources help improve the statistical rigor of evidence analysis techniques and provide benchmarks for method comparison. The availability of standardized datasets enables more reproducible validation studies across different laboratories and research groups.

Figure 2: Framework for Valid Forensic Inference Systems

Empirical validation constitutes a fundamental requirement for scientifically defensible forensic practice. As demonstrated across multiple forensic disciplines, proper validation must replicate casework conditions and use relevant data to generate meaningful performance metrics. The adoption of standardized frameworks, including the likelihood-ratio approach for evidence evaluation and ISO standards for process quality, supports more transparent and reproducible forensic science.

Significant challenges remain, particularly in addressing the comprehensive assessment of error rates and ensuring proper validation of seemingly intuitive forensic decisions. Future research should focus on determining specific casework conditions and mismatch types that require validation, defining what constitutes relevant data, and establishing the quality and quantity of data required for robust validation [1]. Through continued attention to these issues, the forensic science community can advance toward more demonstrably reliable practices that better serve the justice system.

The validity of a forensic inference system is not inherent in its algorithmic complexity but is fundamentally determined by the relevance and representativeness of the data used in its development and validation. A system trained on pristine, idealized data will invariably fail when confronted with the messy, complex, and often ambiguous reality of casework evidence. This guide examines the critical importance of using data that reflects real-world forensic conditions, exploring this principle through the lens of a groundbreaking benchmarking study on Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs) in forensic science. The performance data and experimental protocols detailed herein provide a framework for researchers and developers to objectively evaluate their own systems against this foundational requirement. As international standards like ISO 21043 emphasize, the entire forensic process—from evidence recovery to interpretation and reporting—must be designed to ensure quality and reliability, principles that are impossible to uphold without relevant data [2].

Experimental Protocols: Benchmarking in a Real-World Context

To understand the performance of any analytical system, one must first examine the rigor of its testing environment. The following protocols from a recent comprehensive benchmarking study illustrate how to structure an evaluation that respects the complexities of forensic practice.

Dataset Construction and Curation

The benchmarking study constructed a diverse question bank of 847 examination-style forensic questions sourced from publicly available academic resources and case studies. This approach intentionally moved beyond single-format, factual recall tests to mimic the variety and unpredictability of real forensic assessments [9].

- Source Material: The dataset was aggregated from leading undergraduate and graduate-level forensic science textbooks, nationally-certified observed structured clinical examinations (OSCEs) from institutions like the University of Jordan Faculty of Medicine, and other academic literature [9].

- Topic Coverage: The questions spanned nine core forensic subdomains to ensure breadth and representativeness. The distribution is detailed in Table 1.

- Modality and Format: The dataset included both text-only (73.4%) and image-based (26.6%) questions. The image-based questions were heavily concentrated in areas like death investigation and autopsy, which require visual assessments of wounds, lividity, and decomposition stages—a critical reflection of casework demands. Most questions (92.2%) were multiple-choice or true/false, while 7.8% were non-choice-based, requiring models to articulate conclusions from case narratives in a manner akin to professional reporting [9].

Model Selection and Evaluation Framework

The study evaluated eleven state-of-the-art open-source and proprietary MLLMs, providing a broad comparison of currently available technologies [9].

- Proprietary Models: GPT-4o, Claude 4 Sonnet, Claude 3.5 Sonnet, Gemini 2.5 Flash, Gemini 2.0 Flash, and Gemini 1.5 Flash.

- Open-Source Models: Llama 4 Maverick 17B-128E Instruct, Llama 4 Scout 17B-16E Instruct, Llama 3.2 90B, Llama 3.2 11B, and Qwen2.5-VL 72B Instruct.

- Prompting Strategies: Each model was evaluated using both direct prompting (requiring an immediate final answer) and chain-of-thought (CoT) prompting (where the model reasons step-by-step before answering). This allowed researchers to assess not just accuracy, but also the reasoning capabilities crucial for complex forensic scenarios [9].

- Scoring and Validation: Responses were scored from 0 (completely incorrect) to 1 (completely correct), with no partial credit awarded for multi-part questions. Automated scoring via an "LLM-as-a-judge" method using GPT-4o was validated through manual revision of a random sample, confirming perfect agreement with human judgment for the sampled responses [9].

Table 1: Forensic Subdomain Representation in the Benchmarking Dataset

| Forensic Subdomain | Number of Questions (n) |

|---|---|

| Death Investigation and Autopsy | 204 |

| Toxicology and Substance Usage | 141 |

| Trace and Scene Evidence | 133 |

| Injury Analysis | 124 |

| Asphyxia and Special Death Mechanisms | 70 |

| Firearms, Toolmarks, and Ballistics | 60 |

| Clinical Forensics | 49 |

| Anthropology and Skeletal Analysis | 38 |

| Miscellaneous/Other | 28 |

Performance Data: A Quantitative Comparison of MLLMs

The results from the benchmarking study provide a clear, data-driven comparison of how different MLLMs perform when tasked with forensic problems. The data underscores a significant performance gap between the most and least capable models and highlights the general limitations of current technology when faced with casework-like complexity.

Table 2: Model Performance on Multimodal Forensic Questions (Direct Prompting)

| Model | Overall Accuracy (%) | Text-Based Question Accuracy (%) | Image-Based Question Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gemini 2.5 Flash | 74.32 ± 2.90 | [Data Not Shown in Source] | [Data Not Shown in Source] |

| Claude 4 Sonnet | [Data Not Shown in Source] | [Data Not Shown in Source] | [Data Not Shown in Source] |

| GPT-4o | [Data Not Shown in Source] | [Data Not Shown in Source] | [Data Not Shown in Source] |

| Qwen2.5-VL 72B Instruct | [Data Not Shown in Source] | [Data Not Shown in Source] | [Data Not Shown in Source] |

| Llama 3.2 11B Vision Instruct Turbo | 45.11 ± 3.27 | [Data Not Shown in Source] | [Data Not Shown in Source] |

The data reveals several key trends:

- Performance Variability: The overall accuracy for direct prompting varied widely, from a low of 45.11% for Llama 3.2 11B to a high of 74.32% for Gemini 2.5 Flash, establishing a performance hierarchy [9].

- Generational Improvement: Newer model generations consistently demonstrated improved performance over their predecessors [9].

- Prompting Efficacy: The utility of Chain-of-Thought prompting was context-dependent. It improved accuracy on text-based and multiple-choice tasks for most models but failed to provide the same benefit for image-based and open-ended questions. This indicates a limitation in the models' ability to conduct grounded visual reasoning [9].

- The Visual Reasoning Deficit: A universal and critical finding was that all models underperformed on image interpretation and nuanced forensic scenarios compared to their performance on text-based tasks. This performance gap directly points to a lack of training on relevant, complex visual data from real casework, which is essential for tasks like injury pattern recognition or trace evidence evaluation [9].

Visualizing the Workflow: From Data to Forensic Inference

The following diagram maps the logical workflow of the benchmarking experiment, illustrating the pathway from dataset construction to the final evaluation of model capabilities and limitations.

Building and validating forensic inference systems requires a specific set of conceptual tools and resources. The following table details key items drawn from the search results that are essential for ensuring that research and development are grounded in the principles of forensic science.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Forensic AI Validation

| Tool/Resource | Function in Research | Role in Ensuring Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| ISO 21043 Standard | Provides international requirements & recommendations for the entire forensic process (vocabulary, analysis, interpretation, reporting) [2]. | Serves as a quality assurance framework, ensuring developed systems align with established forensic best practices and legal expectations. |

| FEPAC Accreditation | A designation awarded by the Forensic Science Education Programs Accreditation Commission after a strict evaluation of forensic science curricula [10]. | Guides the creation of educational and training datasets that meet high, standardized levels of forensic science education. |

| Specialized Forensic Datasets | Curated collections of forensic case data, images, and questions spanning subdomains like toxicology, DNA, and trace evidence [9]. | Provides the essential "ground truth" data for training and testing AI models, ensuring they are exposed to casework-like complexity. |

| Chain-of-Thought Prompting | A technique that forces an AI model to articulate its reasoning process step-by-step before giving a final answer [9]. | Acts as a window into the "black box," allowing researchers to audit the logical validity of a model's inference, a core requirement for judicial scrutiny. |

| Browser Artifact Data | Digital traces of online activity (cookies, history, cache) used in machine learning for criminal behavior analysis [11]. | Provides real-world, behavioral data for developing and testing digital forensics tools aimed at detecting anomalous or malicious intent. |

The empirical data reveals that while MLLMs and other AI systems show emerging potential for forensic education and structured assessments, their limitations in visual reasoning and open-ended interpretation currently preclude independent application in live casework [9]. The performance deficit in image-based tasks is the most telling indicator of a system not yet validated on sufficiently relevant data. For researchers and developers, the path forward is clear: future efforts must prioritize the development of rich, multimodal forensic datasets, domain-targeted fine-tuning, and task-aware prompting to improve reliability and generalizability [9]. The ultimate validation of any forensic inference system lies not in its performance on a standardized test, but in its demonstrable robustness when confronted with the imperfect, ambiguous, and critical reality of forensic evidence.

Validation is a cornerstone of credible forensic science, ensuring that methods and systems produce reliable, accurate, and interpretable results. For forensic inference systems, a robust validation framework must establish three core principles: plausibility, which ensures that analytical claims are logically sound and theoretically grounded; testability, which requires that hypotheses can be empirically examined using rigorous experimental protocols; and generalization, which confirms that findings hold true across different populations, settings, and times. A paradigm shift is underway in forensic science, moving from subjective, experience-based methods toward approaches grounded in relevant data, quantitative measurements, and statistical models [12]. This guide objectively compares validation methodologies by examining supporting experimental data and protocols, providing a structured resource for researchers and developers working to advance forensic data research.

Core Principles of Validation

Plausibility

Plausibility establishes the logical and theoretical foundation of an inference. It demands that the proposed mechanism of action or causal relationship is coherent with established scientific knowledge and that the system's outputs are justifiable. In forensic contexts, this involves using the logically correct framework for evidence interpretation, notably the likelihood-ratio framework [12]. A plausible forensic method must be built on a transparent and reproducible program theory or theory of change that clearly articulates how the evidence is expected to lead to a conclusion [13]. Assessing plausibility is not merely a theoretical exercise; it requires demonstrating that the system's internal logic is sound and that its operation is based on empirically validated principles rather than untested assumptions.

Testability

Testability requires that a system's claims and performance can be subjected to rigorous, empirical evaluation. This principle is operationalized through internal validation, which assesses the reproducibility and optimism of an algorithm within its development data [14]. Key methodologies include cross-validation and bootstrapping, which provide optimism-corrected performance estimates [14]. For forensic tools, testability implies that analytical methods must be empirically validated under casework conditions [12]. This involves designing experiments that explicitly check whether the outcomes along the hypothesised causal pathway are triggered as predicted by the underlying theory [13]. Without rigorous testing protocols, claims of a system's performance remain unverified and scientifically unreliable.

Generalization

Generalization, or external validity, refers to the portability of an inference system's performance to new settings, populations, and times. It moves beyond internal consistency to ask whether the results hold true in the real world. Generalization is not a single concept but encompasses multiple dimensions: temporal validity (performance over time), geographical validity (performance across different institutions or locations), and domain validity (performance across different clinical or forensic contexts) [14]. A crucial insight from clinical research is that assessing generalization requires more than comparing surface-level population characteristics; it demands an understanding of the mechanism of action—why or how an intervention was effective—to determine if that mechanism can be enacted in a new context [13]. Failure to establish generalizability directly hinders the effective use of evidence in decision-making [13].

Comparative Analysis of Validation Methodologies

The table below summarizes the core objectives, key methodologies, and primary stakeholders for each validation principle, highlighting their distinct yet complementary roles in establishing the overall validity of a forensic inference system.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Core Validation Principles

| Validation Principle | Core Objective | Key Methodologies | Primary Stakeholders |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plausibility | Establish logical soundness and theoretical coherence | Likelihood-ratio framework, Program theory development, Logical reasoning analysis [12] [13] | System developers, Theoretical forensic scientists, Peer reviewers |

| Testability | Provide empirical evidence of performance under development conditions | Cross-validation, Bootstrapping, Internal validation [14] | Algorithm developers, Research scientists, Statistical analysts |

| Generalization | Demonstrate performance transportability to new settings, populations, and times | Temporal/Geographical/Domain validation, Mechanism-of-action analysis, External validation [14] [13] | End-users (clinicians, forensic practitioners), Policymakers, Manufacturers |

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Protocol for Assessing Plausibility

Objective: To evaluate the logical coherence of a forensic inference system and its adherence to a sound theoretical framework. Workflow:

- Theory of Change Elicitation: Collaboratively map the system's intended mechanism of action with domain experts. This involves detailing the input data, the processing steps, the hypothesized causal pathways, and the expected output [13].

- Logical Framework Application: Implement the likelihood-ratio framework for evidence interpretation. This framework quantitatively assesses the probability of the evidence under (at least) two competing propositions [12].

- Transparency Audit: Document all assumptions, potential sources of bias, and limitations in the reasoning process. The system should be transparent and reproducible [12].

- Peer Review: Subject the theoretical foundation and logical structure to independent review by domain experts not involved in the development.

Protocol for Assessing Testability via Internal Validation

Objective: To obtain an optimism-corrected estimate of the model's performance on data derived from the same underlying population as the development data. Workflow:

- Data Splitting: Randomly split the available development dataset into k equal parts (folds). For stability, a 10-fold cross-validation repeated 5-10 times is recommended [14].

- Iterative Training and Testing:

- For each repetition, hold out one fold as validation data.

- Train the model on the remaining k-1 folds.

- Apply the trained model to the held-out validation fold and calculate performance metrics (e.g., discriminatio,n calibration).

- Performance Aggregation: Aggregate the performance metrics across all iterations to produce a robust estimate of internal performance.

- Bootstrapping (Alternative): Generate a large number (e.g., 500-2000) of bootstrap samples by sampling from the development data with replacement. Train a model on each bootstrap sample and test it on the original development set to estimate optimism [14].

Protocol for Assessing Generalization via External Validation

Objective: To assess the model's performance on data collected from a different setting, time, or domain than the development data. Workflow:

- Validation Cohort Definition: Secure a fully independent dataset from a distinct source (e.g., a different institution, a later time period, or a different demographic group) [14].

- Pre-Specification of Analysis: Before analysis, define the primary performance metrics (e.g., area under the curve, calibration slope, net benefit) and the acceptable performance thresholds for the intended use.

- Model Application: Apply the locked, fully-specified model (without retraining) to the independent validation cohort.

- Performance Assessment: Calculate the pre-specified performance metrics on the external cohort. A significant drop in performance indicates poor generalizability.

- Mechanism-of-Action Interrogation: If performance is poor, conduct qualitative or scoping studies to understand how the system's mechanism of action interacts with the new context, rather than just cataloging population differences [13].

Visualization of Validation Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the sequential and interconnected nature of a comprehensive validation strategy for forensic inference systems, from foundational plausibility to external generalization.

Diagram 1: Sequential Validation Workflow for Forensic Systems

The following table details key methodological solutions and resources essential for conducting rigorous validation studies in forensic inference research.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Forensic System Validation

| Reagent / Resource | Function in Validation | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Likelihood-Ratio Framework | Provides a logically sound and transparent method for quantifying the strength of evidence under competing propositions [12]. | Core to establishing Plausibility in evidence interpretation. |

| Cross-Validation & Bootstrapping | Statistical techniques for assessing internal validity and correcting for over-optimism in performance estimates during model development [14]. | Core to establishing Testability. |

| External Validation Cohorts | Independent datasets from different settings, times, or domains used to assess the real-world transportability of a model's performance [14]. | Essential for demonstrating Generalization. |

| Program Theory / Theory of Change | A structured description of how an intervention or system is expected to achieve its outcomes, mapping the causal pathway from input to result [13]. | Foundational for assessing Plausibility and guiding validation. |

| Process Evaluation Methods | Qualitative and mixed-methods approaches used to understand how a system functions in context, revealing its mechanism of action [13]. | Critical for diagnosing poor Generalization and improving systems. |

| Fuzzy Logic-Random Forest Hybrids | A modeling approach that combines expert-driven, interpretable rule-based reasoning (fuzzy logic) with powerful empirical learning (Random Forest) [15]. | An example of a testable, interpretable model architecture for complex decision support. |

The rigorous validation of forensic inference systems is a multi-faceted endeavor demanding evidence of plausibility, testability, and generalization. By adopting the structured guidelines, experimental protocols, and tools outlined in this guide, researchers and developers can move beyond superficial claims of performance. The comparative data and workflows demonstrate that these principles are interdependent; a plausible system must be testable, and a testable system must prove its worth through generalizability. As the field continues its paradigm shift toward data-driven, quantitative methods [12], a steadfast commitment to this comprehensive validation framework is essential for building trustworthy, effective, and just forensic science infrastructures.

The Likelihood Ratio Framework for Interpreting Forensic Evidence

The Likelihood Ratio (LR) framework is a quantitative method for evaluating the strength of forensic evidence by comparing two competing propositions. It provides a coherent statistical foundation for forensic interpretation, aiming to reduce cognitive bias and offer transparent, reproducible results. This framework assesses the probability of observing the evidence under the prosecution's hypothesis versus the probability of observing the same evidence under the defense's hypothesis [16]. The LR framework has gained substantial traction within the forensic science community, particularly in Europe, and is increasingly evaluated for adoption in the United States as a means to enhance objectivity [17] [18]. Its application spans numerous disciplines, from the well-established use in DNA analysis to emerging applications in pattern evidence fields such as fingerprints, bloodstain pattern analysis, and digital forensics [17] [18] [19].

This guide objectively compares the performance of the LR framework across different forensic disciplines, contextualized within the broader thesis of validating forensic inference systems. For researchers and scientists, understanding the empirical performance, underlying assumptions, and validation requirements of the LR framework is paramount. The framework's utility is not uniform; it rests on a continuum of scientific validity that varies significantly with the discipline's foundational knowledge and the availability of robust data [18] [19]. We present supporting experimental data, detailed methodologies, and essential research tools to critically appraise the LR framework's application in modern forensic science.

Core Principles and Mathematical Formulation

The Likelihood Ratio provides a measure of the probative value of the evidence. Formally, it is defined as the ratio of two probabilities [16] [20]:

LR = P(E | Hp) / P(E | Hd)

Here, P(E | Hp) is the probability of observing the evidence (E) given the prosecution's hypothesis (Hp) is true. Conversely, P(E | Hd) is the probability of observing the evidence (E) given the defense's hypothesis (Hd) is true. The LR is a valid measure of probative value because, by Bayes' Theorem, it updates prior beliefs about the hypotheses to posterior beliefs after considering the evidence [20]. The LR itself does not require assumptions about the prior probabilities of the hypotheses, which is a key reason for its popularity in forensic science [20].

The interpretation of the LR value is straightforward [16]:

- LR > 1: The evidence supports the prosecution's hypothesis (Hp).

- LR = 1: The evidence is neutral; it supports neither hypothesis.

- LR < 1: The evidence supports the defense's hypothesis (Hd).

Verbal equivalents have been proposed to communicate the strength of the LR in court, though these should be used only as a guide [16]. The following table outlines a common scale for interpretation.

Table 1: Interpretation of Likelihood Ratio Values

| Likelihood Ratio (LR) Value | Verbal Equivalent | Support for Proposition Hp |

|---|---|---|

| LR > 10,000 | Very Strong | Very Strong Support |

| LR 1,000 - 10,000 | Strong | Strong Support |

| LR 100 - 1,000 | Moderately Strong | Moderately Strong Support |

| LR 10 - 100 | Moderate | Moderate Support |

| LR 1 - 10 | Limited | Limited Support |

| LR = 1 | Inconclusive | No Support |

Logical Framework of the Likelihood Ratio

The diagram below illustrates the logical process of evidence evaluation using the Likelihood Ratio framework, from the initial formulation of propositions to the final interpretation.

Comparative Performance Across Forensic Disciplines

The performance and validity of the LR framework are not consistent across all forensic disciplines. Its effectiveness is heavily dependent on the existence of a solid scientific foundation, validated statistical models, and reliable data to compute the probabilities. The following table provides a comparative summary of the LR framework's application in key forensic disciplines, based on current research and validation studies.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of the LR Framework Across Forensic Disciplines

| Discipline | Scientific Foundation | Model Availability | Reported Performance/Data | Key Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Analysis | Strong (Biology, Genetics) | Well-established [16] | Single source: LR = 1/RMP, where RMP is Random Match Probability [16]. High accuracy and reproducibility. | Minimal; considered a "gold standard." |

| Fingerprints | Moderate (Pattern Analysis) | Emerging [17] [18] | LR values can vary based on subjective choices of models and assumptions [17]. Lack of established statistical models for pattern formation [18]. | Subjectivity in model selection; difficulty in quantifying uncertainty [17] [18]. |

| Bloodstain Pattern Analysis (BPA) | Developing (Fluid Dynamics) | Limited [19] | Rarely used in practice. Research focuses on activity-level questions rather than source identification [19]. | Lack of public data; incomplete understanding of underlying physics (fluid dynamics) [19]. |

| Digital Forensics (Social Media) | Emerging (Computer Science) | In development [21] | Use of AI/ML (BERT, CNN) for evidence analysis. Effective in cyberbullying, fraud detection [21]. | Data volume, privacy laws (GDPR), data integrity [21]. |

| Bullet & Toolmark Analysis | Weak (Material Science) | Limited [18] | LR may rest on unverified assumptions. Fundamental scientific underpinnings are absent [18]. | No physical/statistical model for striation formation; high subjectivity [18]. |

Key Insights from Comparative Analysis

The data reveals a clear distinction between the application of the LR framework in disciplines with strong scientific underpinnings, like DNA analysis, and those with developing foundations, like pattern evidence. For DNA, the model is straightforward, and the probabilities are based on well-understood population genetics, leading to high reproducibility [16]. In contrast, for fingerprints and bullet striations, the LR relies on subjective models because the fundamental processes that create these patterns are not fully understood or quantifiable [18]. This introduces a degree of subjectivity, where two experts might arrive at different LRs for the same evidence [17]. In emerging fields like BPA, the primary challenge is a lack of data and a need for a deeper understanding of the underlying physics (fluid dynamics) to build reliable models [19].

Experimental Protocols for LR Validation

Validating the LR framework requires specific experimental protocols designed to test its reliability, accuracy, and repeatability across different evidence types. Below are detailed methodologies for key experiments cited in the comparative analysis.

Protocol 1: Validation of SNP Panels for Kinship Analysis

This protocol is based on research developing a 9000-SNP panel for distant kinship inference in East Asian populations [22].

- Marker Selection: Screen SNPs from major genotyping arrays. Apply filters for autosomal location, MAF > 0.3, and high genotyping quality. Finalize a panel with markers evenly distributed across all autosomes.

- Sample Collection & Genotyping: Collect pedigree samples with known relationships. Genotype samples using a high-density SNP array.

- Data Processing: Use software to calculate kinship coefficients and identity-by-descent. Impute missing genotypes if necessary.

- Performance Evaluation: Test the panel's ability to distinguish relatives from non-relatives. Determine the maximum degree of kinship that can be reliably identified.

- Validation: Adhere to established guidelines, following the validation guidelines of the Scientific Working Group on DNA Analysis Methods [22].

Protocol 2: Black-Box Studies for Pattern Evidence

Promoted by U.S. National Research Council reports, this protocol is essential for estimating error rates in subjective disciplines [17].

- Study Design: Construct control cases where the ground truth is known to researchers but not participating practitioners.

- Evidence Preparation: Prepare a set of evidence samples that represent a realistic range of casework complexity and quality.

- Blinded Analysis: Practitioners analyze the control cases as surrogates for real casework, applying the LR framework.

- Data Collection: Collect all LR values or conclusions provided by the practitioners.

- Analysis: Calculate empirical error rates and assess the variability in LR outputs across practitioners and across different ground truth conditions. This provides a collective performance metric for the discipline [17].

Protocol 3: AI-Driven Analysis of Social Media Evidence

This protocol employs machine learning for forensic analysis of social media data in criminal investigations [21].

- Data Collection: Gather social media data, including text posts, images, and metadata, under appropriate legal frameworks.

- Data Preprocessing: Clean data, handle missing values, and extract features.

- Model Selection:

- NLP: Use BERT for contextual understanding in cyberbullying or misinformation detection.

- Image Analysis: Use Convolutional Neural Networks for facial recognition or tamper detection.

- Model Training & Testing: Train models on labeled datasets and test their performance on held-out data.

- Validation: Demonstrate effectiveness through empirical case studies and ensure the process adheres to ethical and legal standards for court admissibility [21].

Uncertainty and the Assumptions Lattice

A critical challenge in applying the LR framework is managing uncertainty. The "lattice of assumptions" and "uncertainty pyramid" concept provides a structure for this [17].

- Lattice of Assumptions: An LR calculation is never made in a vacuum. It is based on a chain of assumptions regarding the choice of statistical model, population databases, and features considered. This chain can be visualized as a lattice, where each node represents a specific set of assumptions.

- Uncertainty Pyramid: By exploring the range of LR values obtained from different reasonable models within the lattice, an "uncertainty pyramid" is constructed. The base represents a wide range of results from many models, and the apex represents a narrow range from highly specific, justified models. This analysis is crucial for assessing the fitness for purpose of a reported LR [17].

The diagram below visualizes this framework for assessing uncertainty in LR evaluation.

The Researcher's Toolkit

Implementing and validating the LR framework requires a suite of specialized reagents, software, and data resources. The following table details key solutions essential for research in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for LR Framework Research

| Tool Name/Type | Specific Example | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| SNP Genotyping Array | Infinium Global Screening Array (GSA) [22] | High-throughput genotyping to generate population data for DNA-based LR calculations. |

| Hybrid Capture Sequencing Panel | Custom 9000 SNP Panel [22] | Targeted sequencing for specific applications like distant kinship analysis. |

| Bayesian Network Software | - | To automatically derive LRs for complex, dependent pieces of evidence [20]. |

| AI/ML Models for NLP | BERT [21] | Provides contextual understanding of text from social media for evidence evaluation. |

| AI/ML Models for Image Analysis | Convolutional Neural Networks [21] | Used for facial recognition and tamper detection in multimedia evidence. |

| Curated Reference Databases | Bloodstain Pattern Dataset [19] | Publicly available data for modeling and validating LRs in specific disciplines. |

| Statistical Analysis Tools | R, Python | For developing statistical models, calculating LRs, and performing uncertainty analyses. |

| 3,4-Dimethyl-2-hexene | 3,4-Dimethyl-2-hexene|C8H16 | |

| (Diethylamino)methanol | (Diethylamino)methanol, CAS:15931-59-6, MF:C5H13NO, MW:103.16 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The Likelihood Ratio framework represents a significant advancement toward quantitative and transparent forensic science. However, its performance is not a binary state of valid or invalid; it exists on a spectrum dictated by the scientific maturity of each discipline. For DNA evidence, the LR is a robust and well-validated tool. For pattern evidence and other developing disciplines, it remains a prospective framework whose valid application is contingent on substantial research investment. This includes building foundational scientific knowledge, creating shared data resources, developing objective models, and, crucially, conducting comprehensive uncertainty analyses. For researchers and scientists, the ongoing validation of forensic inference systems must focus on these areas to ensure that the LR framework fulfills its promise of providing reliable, measurable, and defensible evidence in legal contexts.

Addressing the Historical Lack of Validation in Feature-Comparison Methods

Feature-comparison methods have long been a cornerstone of forensic science, enabling experts to draw inferences from patterns in evidence such as fingerprints, tool marks, and digital data. The historical application of these methods, however, has often been characterized by a significant lack of robust validation protocols. This validation gap has raised critical questions about the reliability and scientific foundation of forensic evidence presented in legal contexts [23]. Without rigorous, empirical demonstration that a method consistently produces accurate and reproducible results, the conclusions drawn from its application remain open to challenge.

The emergence of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) in forensic science has brought the issue of validation into sharp focus. Modern standards demand that any method, whether traditional or AI-enhanced, must undergo thorough validation to ensure its outputs are reliable, transparent, and fit for purpose in the criminal justice system [23] [24]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of validation approaches, detailing experimental protocols and metrics essential for establishing the scientific validity of feature-comparison methods.

Comparative Analysis of Method Performance

The integration of AI into forensic workflows has demonstrated quantifiable improvements in accuracy and efficiency across various applications. The table below summarizes key performance metrics from recent studies, contrasting different methodological approaches.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Forensic Feature-Comparison Methods

| Forensic Application | Methodology | Key Performance Metrics | Limitations & Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fingerprint Analysis | Traditional AFIS-based workflow | Relies on expert-driven minutiae comparison and manual verification [23]. | Susceptible to human error; limited when dealing with partial or low-quality latent marks [23]. |

| Fingerprint Analysis | AI-enhanced predictive models (e.g., CNNs) | Rank-1 identification rates of ~80% (FVC2004) and 84.5% (NIST SD27) for latent fingerprints; can generate investigative leads (e.g., demographic classification) when conventional matching fails [23]. | Requires statistical validation, bias detection, and explainability; must meet legal admissibility criteria [23]. |

| Wound Analysis | AI-based classification systems | 87.99–98% accuracy in gunshot wound classification [25]. | Performance variable across different applications [25]. |

| Post-Mortem Analysis | Deep Learning on medical imagery | 70–94% accuracy in head injury detection and cerebral hemorrhage identification from Post-Mortem CT (PMCT) scans [25]. | Difficulty recognizing specific conditions like subarachnoid hemorrhage; limited by small sample sizes in studies [25]. |

| Forensic Palynology | Traditional microscopic analysis | Hindered by manual identification, slow processing, and human error [24]. | Labor-intensive; restricted application in casework [24]. |

| Forensic Palynology | CNN-based deep learning | >97–99% accuracy in automated pollen grain classification [24]. | Performance depends on large, diverse, well-curated datasets; challenges with transferability to degraded real-world samples [24]. |

| Diatom Testing | AI-enhanced analysis | Precision scores of 0.9 and recall scores of 0.95 for drowning case analysis [25]. | Dependent on quality and scope of training data [25]. |

A critical insight from this data is that AI serves best as an enhancement rather than a replacement for human expertise [25]. The highest levels of performance are achieved when algorithmic capabilities are combined with human oversight, creating a hybrid workflow that leverages the strengths of both.

Experimental Protocols for Method Validation

To address the historical validation gap, any new or existing feature-comparison method must be subjected to a rigorous comparison of methods experiment. The primary purpose of this protocol is to estimate the inaccuracy or systematic error of a new test method against a comparative method [26].

Core Experimental Design

- Comparative Method Selection: The choice of a comparative method is foundational. An ideal comparator is a reference method, whose correctness is well-documented. When using a routine method for comparison, any large, medically unacceptable differences must be investigated to determine which method is at fault [26].

- Sample Selection and Size: A minimum of 40 different patient specimens is recommended. These specimens should be carefully selected to cover the entire working range of the method and represent the spectrum of conditions (e.g., diseases, environmental degradation) expected in routine practice. The quality and range of specimens are more critical than the absolute number. Using 100-200 specimens is advisable to thoroughly assess method specificity [26].

- Measurement and Timing: While single measurements are common, performing duplicate analyses on different samples or in different analytical runs is ideal, as it helps identify sample mix-ups or transposition errors. The experiment should be conducted over a minimum of 5 days, and ideally up to 20 days, to capture inter-day performance variations. Specimens must be analyzed within two hours by both methods to avoid stability-related discrepancies, unless specific preservatives or handling protocols are established [26].

Data Analysis and Interpretation

- Graphical Analysis: The data should first be visualized. A difference plot (test result minus comparative result vs. comparative result) is used when methods are expected to agree one-to-one. A comparison plot (test result vs. comparative result) is used when a perfect correlation is not expected. This visual inspection helps identify outliers and the general relationship between methods [26].

- Statistical Calculations:

- For a wide analytical range: Use linear regression to obtain the slope (b), y-intercept (a), and standard deviation of the points about the line (sy/x). The systematic error (SE) at a critical decision concentration (Xc) is calculated as: Yc = a + bXc, then SE = Yc - Xc* [26].

- For a narrow analytical range: Calculate the average difference (bias) between the methods using a paired t-test. The accompanying standard deviation of the differences describes the distribution of these between-method differences [26].

- The correlation coefficient (r) is more useful for verifying that the data range is wide enough to provide reliable regression estimates (e.g., r ≥ 0.99) than for judging method acceptability [26].

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for a robust comparison of methods experiment:

Figure 1. Experimental Validation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful validation and application of feature-comparison methods, particularly in AI-driven domains, rely on a foundation of specific tools and materials.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Forensic Feature-Comparison Research

| Item / Solution | Function in Research & Validation |

|---|---|

| Reference Datasets | Well-characterized, standardized datasets (e.g., NIST fingerprint data, pollen image libraries) used as a ground truth for training AI models and benchmarking method performance against a known standard [24]. |

| Validated Comparative Method | An existing method with documented performance characteristics, used as a benchmark to estimate the systematic error and relative accuracy of a new test method during validation [26]. |

| Curated Patient/Evidence Specimens | A panel of real-world specimens that cover the full spectrum of expected variation (e.g., in quality, type, condition) used to assess method robustness and generalizability beyond ideal samples [26]. |

| Machine Learning Algorithms | Core computational tools (e.g., CNNs for image analysis, tree ensembles like XGBoost for chemical data) that perform automated feature extraction, classification, and regression tasks [25] [23]. |

| Statistical Analysis Software | Software capable of performing linear regression, paired t-tests, and calculating metrics like precision and recall, which are essential for quantifying method performance and error [26]. |

| High-Quality Training Data | Large, diverse, and accurately labeled datasets used to train AI models. The quality and size of this data are critical factors limiting the ultimate accuracy and generalizability of the model [24]. |

| 1-(3-Fluorophenyl)imidazoline-2-thione | 1-(3-Fluorophenyl)imidazoline-2-thione, CAS:17452-26-5, MF:C9H7FN2S, MW:194.23 g/mol |

| 2,3,6-Trinitrotoluene | 2,3,6-Trinitrotoluene|CAS 18292-97-2|Research Grade |

The journey toward robust validation in forensic feature-comparison is ongoing. While AI technologies offer remarkable gains in accuracy and efficiency for tasks ranging from fingerprint analysis to palynology, they also demand a new, more rigorous standard of validation. This includes transparent reporting of performance metrics on standardized datasets, explicit testing for algorithmic bias, and the development of explainable AI systems whose reasoning can be understood and challenged in a court of law. The future of reliable forensic inference lies not in choosing between human expertise and algorithmic power, but in constructing validated, hybrid workflows that leverage the strengths of both, thereby closing the historical validation gap and strengthening the foundation of forensic science.

Implementing Validation Protocols Across Forensic Disciplines

In the rigorous fields of forensic inference and pharmaceutical research, systematic validation planning forms the foundational bridge between theoretical requirements and certifiable results. This process provides the documented evidence that a system, whether a DNA analysis technique or a drug manufacturing process, consistently produces outputs that meet predetermined specifications and quality attributes [27] [28]. For researchers and scientists developing next-generation forensic inference systems, a robust validation framework is not merely a regulatory formality but a scientific necessity. It ensures that analytical results—from complex DNA mixture interpretations to AI-driven psychiatric treatment predictions—are reliable, reproducible, and legally defensible [15] [29].

The stakes for inadequate validation are particularly high in regulated environments. Studies indicate that fixing a requirement defect after development can cost up to 100 times more than addressing it during the analysis phase [30]. Furthermore, in pharmaceuticals, a failure to validate can result in regulatory actions, including the halt of drug distribution [31]. This guide objectively compares methodologies for establishing validation plans that meet the stringent demands of both forensic science and drug development, supporting a broader thesis on validating inference systems that handle critical human data.

Comparative Analysis of Validation Frameworks and Their Applications

Validation principles, though universally critical, are applied differently across scientific domains. The following table compares the core frameworks and their relevance to forensic and pharmaceutical research.

Table 1: Comparison of Validation Frameworks Across Domains

| Domain | Core Framework | Primary Focus | Key Strengths | Relevance to Forensic Inference Systems |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Software & Requirements Engineering | Requirements Validation [30] [32] | Ensuring requirements define the system the customer really wants. | Prevents costly rework; Ensures alignment with user needs. | High - Ensures system specifications meet forensic practitioners' needs. |

| Pharmaceutical Manufacturing | Process Validation (Stages 1-3) & IQ/OQ/PQ [27] [28] | Ensuring processes consistently produce quality products. | Rigorous, staged approach; Strong regulatory foundation (FDA). | High - Provides a model for validating entire analytical workflows. |

| Medical Device Development | Validation & Test Engineer (V&TE) [33] | Ensuring devices meet safety, efficacy, and regulatory compliance. | Integrates testing and documentation; Focus on traceability. | Very High - Directly applicable to validating forensic instruments/software. |

| General R&D (Cross-Domain) | Validation Planning (7-Element Framework) [34] | Providing a clear execution framework for any validation project. | Flexible and adaptable; Emphasizes risk assessment and resources. | Very High - A versatile template for planning forensic method validation. |

A hybrid approach that draws on the strengths of each framework is often most effective. For instance, a forensic DNA analysis system would benefit from the rigorous Process Design and Process Qualification stages from pharma [28], the traceability matrices emphasized in medical device development [33], and the requirement checking (validity, consistency, completeness) from software engineering [32].

Core Components of a Systematic Validation Plan

A robust validation plan is a strategic document that outlines the entire pathway from concept to validated state. Based on synthesis across industries, a comprehensive plan must include these core elements, as visualized in the workflow below.

Systematic Validation Planning Workflow

Foundational Elements

- Clear Validation Objectives: The plan must start with a concise statement of what is being validated and the success criteria. An example for a forensic system would be: "Validate the hybrid fuzzy logic-Random Forest model for predicting psychiatric treatment order outcomes with >95% accuracy" [15] [34].

- Defined Roles and Responsibilities: A RACI matrix (Responsible, Accountable, Consulted, Informed) is crucial for defining involvement across cross-functional teams of researchers, QA, and IT [34].

- Risk Assessment Strategy: A risk-based approach prioritizes resources on systems with the highest impact on product quality or patient safety. This aligns with ICH Q9 guidance, encouraging assessment of failure severity, likelihood, and detectability [34].

Execution and Control Elements

- Detailed Validation Deliverables: This includes documents like the User Requirements Specification (URS), Functional Requirements Specification (FRS), and various qualification protocols that create an auditable trail [33] [34].

- Acceptance Criteria and Test Plans: Criteria must be objective and measurable. For a forensic tool, this could be: "The system must correctly identify contributor DNA profiles in 99.9% of single-source samples" [28] [34].

- Change Control and Deviation Management: Formal processes are required to assess, document, and approve any changes to a validated system, ensuring it remains in a state of control [31] [34].

- Timeline and Resource Planning: Realistic planning accounts for protocol drafting, test execution, reviews, and contingencies for retests, preventing critical path delays [34].

Experimental Protocols for Key Validation Activities

Protocol for Requirements Analysis and Validation

The foundation of any valid system is a correct and complete set of requirements.

- Objective: To ensure the defined requirements for an inference system are valid, consistent, complete, realistic, and verifiable [32].

- Methodology:

- Elicitation: Conduct structured interviews and workshops with stakeholders (e.g., forensic analysts, legal experts) to gather needs [30].

- Documentation: Categorize requirements into Functional (what the system must do) and Non-functional (performance, security, usability) [30].

- Validation Techniques:

- Systematic Reviews: A team of reviewers systematically analyzes requirements for errors and inconsistencies [32].

- Prototyping: Develop an executable model to demonstrate functionality to end-users for feedback [32].

- Test-Case Generation: Draft tests based on requirements to check their verifiability. Difficult-to-test requirements often need reconsideration [32].

- Outputs: A validated Requirements Document and a Traceability Matrix to link requirements to their origin and future tests [30] [33].

Protocol for the IQ/OQ/PQ Qualification Process

This widely adopted protocol, central to pharmaceutical and medical device validation, is highly applicable for qualifying forensic instruments and software systems.

- Objective: To provide documented evidence that equipment is installed correctly (IQ), operates as intended (OQ), and performs consistently in its operational environment (PQ) [27] [28].

- Methodology:

- Installation Qualification (IQ): Verify that the system or equipment is received as specified, installed correctly, and that all documentation (manuals, calibration plans) is in place [27] [28].

- Operational Qualification (OQ): Verify that the system functions as intended across all anticipated operating ranges. Test all functions, including alarms and interlocks. For a forensic software, this involves testing under minimum, maximum, and normal data loads [27] [28].

- Performance Qualification (PQ): Demonstrate that the system consistently produces results that meet acceptance criteria under actual production conditions. For a DNA sequencer, this would involve running multiple batches of control samples to prove consistency and accuracy [27] [28].

- Outputs: Executed and approved IQ, OQ, and PQ Protocols and Reports [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials for Validation

The following reagents and solutions are fundamental for conducting experiments in forensic and pharmaceutical validation research.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Validation Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function in Validation | Example Application in Forensic/Pharma Research |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standard Materials | Provides a known, traceable benchmark for calibrating equipment and verifying method accuracy. | Certified DNA standards for validating a new STR profiling kit [29]. |

| Control Samples (Positive/Negative) | Monitors assay performance; confirms expected outcomes and detects contamination or failure. | Using known positive and negative DNA samples in every PCR batch to validate the amplification process. |

| Process-Specific Reagents | Challenges the process under validation to ensure it can handle real-world variability. | Specific raw material blends used during Process Performance Qualification (PPQ) in drug manufacturing [28]. |

| Calibration Kits & Solutions | Ensures analytical instruments are measuring accurately and within specified tolerances. | Solutions with known concentrations for calibrating mass spectrometers used in toxicology or metabolomics [29]. |

| Data Validation Sets | Used to test and validate computational models, ensuring predictions are accurate and reliable. | A curated set of 176 court judgments used to validate a hybrid AI model for predicting treatment orders [15]. |

| 2,2,2-Trifluoro-1-(furan-2-yl)ethanone | 2,2,2-Trifluoro-1-(furan-2-yl)ethanone|CAS 18207-47-1 | 2,2,2-Trifluoro-1-(furan-2-yl)ethanone (CAS 18207-47-1), a fluorinated ketone for organic synthesis. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| 1-(2-hydroxyphenyl)-3-phenylthiourea | 1-(2-Hydroxyphenyl)-3-phenylthiourea|CAS 17073-34-6 |

Systematic validation planning is a multidisciplinary discipline that is indispensable for building confidence in the systems that underpin forensic science and pharmaceutical development. The comparative analysis reveals that while domains like pharma [28] and medical devices [33] offer mature, regulatory-tested frameworks, the core principles of clear objectives, risk assessment, rigorous testing, and thorough documentation are universal. For researchers, adopting and adapting these structured plans is not a constraint on innovation but a enabler, ensuring that complex inference systems and analytical methods produce data that is scientifically sound and legally robust. The future of validation in these fields will increasingly integrate AI and machine learning, as seen in emerging research [15] [29], demanding even more sophisticated validation protocols to ensure these powerful tools are used reliably and ethically.

The escalating global incidence of drug trafficking and substance abuse necessitates the development of advanced, reliable, and efficient drug screening methodologies for forensic investigations [35]. Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) has long been a cornerstone technique in forensic drug analysis due to its high specificity and sensitivity [35]. However, conventional GC-MS methods are often hampered by extensive analysis times, which can delay law enforcement responses and judicial processes [35]. This case study examines the development and validation of a rapid GC-MS method that significantly reduces analysis time while maintaining, and even enhancing, the analytical rigor required for forensic evidence. Framed within the broader context of validating forensic inference systems, this analysis provides a template for evaluating emerging analytical technologies against established standards and practices. The methodology and performance data presented here offer forensic researchers and drug development professionals a benchmark for implementing accelerated screening protocols in their laboratories.

Method Comparison: Rapid vs. Conventional GC-MS

Experimental Protocol and Instrumentation

The core experimental protocol for the rapid GC-MS method was developed using an Agilent 7890B gas chromatograph system coupled with an Agilent 5977A single quadrupole mass spectrometer [35]. The system was equipped with a 7693 autosampler and an Agilent J&W DB-5 ms column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm). Helium (99.999% purity) served as the carrier gas at a fixed flow rate of 2 mL/min [35].

Data acquisition was managed using Agilent MassHunter software (version 10.2.489) and Agilent Enhanced ChemStation software (Version F.01.03.2357) for data collection and processing. Critical to the identification process, library searches were conducted using the Wiley Spectral Library (2021 edition) and Cayman Spectral Library (September 2024 edition) [35].

For comparative validation, the same instrumental setup was used to run a conventional GC-MS method, an in-house protocol employed by the Dubai Police forensic laboratories, to directly determine limits of detection (LOD) and performance characteristics [35].

Key Parameter Optimization

The reduction in analysis time from 30 minutes to 10 minutes was achieved primarily through strategic optimization of the temperature program and operational parameters while using the same 30-m DB-5 ms column as the conventional method [35]. Temperature programming and carrier gas flow rates were systematically refined through a trial-and-error process to shorten analyte elution times without compromising separation efficiency [35].

Table 1: Comparative GC-MS Parameters for Seized Drug Analysis

| Parameter | Conventional GC-MS Method | Rapid GC-MS Method |

|---|---|---|

| Total Analysis Time | 30 minutes | 10 minutes |

| Oven Temperature Program | Not specified in detail | Optimized to reduce runtime |

| Carrier Gas Flow Rate | Not specified in detail | Optimized (Helium at 2 mL/min) |

| Chromatographic Column | Agilent J&W DB-5 ms (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm) | Agilent J&W DB-5 ms (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm) |

| Injection Mode | Not specified | Not specified |

| Data System | Not specified | Agilent MassHunter & Enhanced ChemStation |

Sample Preparation Workflow

The sample preparation protocol was designed to handle both solid seized materials and trace samples from drug-related items. The process involves liquid-liquid extraction with methanol, which is suitable for a broad range of analytes [35].

Performance Validation and Comparative Metrics

Analytical Sensitivity and Detection Limits

A comprehensive validation study demonstrated that the rapid GC-MS method offers significant improvements in detection sensitivity for key controlled substances compared to conventional approaches [35]. The method achieved a 50% improvement in the limit of detection for critical substances like Cocaine and Heroin [35].

Table 2: Analytical Performance Metrics for Rapid vs. Conventional GC-MS

| Performance Metric | Conventional GC-MS Method | Rapid GC-MS Method |

|---|---|---|

| Limit of Detection (Cocaine) | 2.5 μg/mL | 1.0 μg/mL |

| Limit of Detection (Heroin) | Not specified | Improved by ≥50% |

| Analysis Time per Sample | 30 minutes | 10 minutes |

| Repeatability (RSD) | Not specified | < 0.25% for stable compounds |

| Match Quality Scores | Not specified | > 90% across tested concentrations |

| Carryover Assessment | Not fully validated | Systematically evaluated |

For cocaine, the rapid method achieved a detection threshold of 1 μg/mL compared to 2.5 μg/mL with the conventional method [35]. This enhanced sensitivity is particularly valuable for analyzing trace samples collected from drug-related paraphernalia.

Precision, Reproducibility, and Real-World Application

The method exhibited excellent repeatability and reproducibility with relative standard deviations (RSDs) of less than 0.25% for retention times of stable compounds under operational conditions [35]. This high level of precision is critical for reliable compound identification in forensic casework.

When applied to 20 real case samples from Dubai Police Forensic Labs, the rapid GC-MS method accurately identified diverse drug classes, including synthetic opioids and stimulants [35]. The identification reliability was demonstrated through match quality scores that consistently exceeded 90% across all tested concentrations [35]. The method successfully analyzed 10 solid samples and 10 trace samples collected from swabs of digital scales, syringes, and other drug-related items [35].

Comprehensive Validation Framework

Independent validation research from the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) confirms that a proper validation framework for rapid GC-MS in seized drug screening should assess nine critical components: selectivity, matrix effects, precision, accuracy, range, carryover/contamination, robustness, ruggedness, and stability [36]. This comprehensive approach ensures the technology meets forensic reliability standards.

Studies meeting these validation criteria have demonstrated that retention time and mass spectral search score % RSDs were ≤ 10% for both precision and robustness studies [36]. The validation template developed by NIST is publicly available to reduce implementation barriers for forensic laboratories adopting this technology [36].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of the rapid GC-MS method for seized drug analysis requires specific reagents, reference materials, and instrumentation. The following table details the essential components of the research toolkit and their respective functions in the analytical workflow.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for Rapid GC-MS Drug Analysis

| Item | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| GC-MS System | Core analytical instrument for separation and detection | Agilent 7890B GC + 5977A MSD; DB-5 ms column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm) [35] |

| Certified Reference Standards | Target compound identification and quantification | Tramadol, Cocaine, Heroin, MDMA, etc. (e.g., from Sigma-Aldrich/Cerilliant) [35] |

| Mass Spectral Libraries | Compound identification via spectral matching | Wiley Spectral Library (2021), Cayman Spectral Library (2024) [35] |

| Extraction Solvent | Sample preparation and compound extraction | Methanol (99.9% purity) [35] |

| Carrier Gas | Mobile phase for chromatographic separation | Helium (99.999% purity) [35] |

| Data Acquisition Software | System control, data collection, and processing | Agilent MassHunter, Agilent Enhanced ChemStation [35] |

| 1-Hydroxy-4-sulfonaphthalene-2-diazonium | 1-Hydroxy-4-sulfonaphthalene-2-diazonium, CAS:16926-71-9, MF:C10H7N2O4S+, MW:251.24 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 3-Methoxy-4-hydroxyphenylglycolaldehyde | 3-Methoxy-4-hydroxyphenylglycolaldehyde, CAS:17592-23-3, MF:C9H10O4, MW:182.17 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Inference Pathways in Forensic Drug Analysis

The validated rapid GC-MS method serves as a critical node within a larger forensic inference system. The analytical results feed into investigative and legal decision-making processes, supported by a framework of methodological rigor and statistical confidence.

The validation case study demonstrates that the rapid GC-MS method represents a significant advancement in forensic drug analysis, effectively addressing the critical need for faster turnaround times without compromising analytical accuracy. The threefold reduction in analysis time (from 30 to 10 minutes), coupled with improved detection limits for key substances like cocaine, positions this technology as a transformative solution for forensic laboratories grappling with case backlogs [35].

The comprehensive validation framework—assessing selectivity, precision, accuracy, robustness, and other key parameters—provides the necessary foundation for admissibility in judicial proceedings [36]. Furthermore, the method's successful application to diverse real-world samples, including challenging trace evidence, underscores its practical utility in operational forensic contexts [35]. As forensic inference systems continue to evolve, the integration of such rigorously validated, high-throughput analytical methods will be essential for supporting timely and scientifically defensible conclusions in the administration of justice.

The pursuit of precision in forensic science has catalyzed the development of sophisticated genetic tools for ancestry inference and personal identification. Within this landscape, Deletion/Insertion Polymorphisms (DIPs) have emerged as powerful markers that combine desirable characteristics of both Short Tandem Repeats (STRs) and Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) [37] [38]. This case study examines the developmental validation of a specialized 60-panel DIP assay tailored for forensic applications in East Asian populations, objectively comparing its performance against alternative genetic systems and providing detailed experimental data to support forensic inference systems.

DIPs, also referred to as Insertion/Deletion polymorphisms (InDels), represent the second most abundant DNA polymorphism in humans and are characterized by their biallelic nature, low mutation rate (approximately 10â»â¸), and absence of stutter peaks during capillary electrophoresis analysis [37] [38]. These properties make them particularly valuable for analyzing challenging forensic samples, including degraded DNA and unbalanced mixtures where traditional STR markers face limitations [38]. The 60-panel DIP system was specifically designed to provide enhanced resolution for biogeographic ancestry assignment while maintaining robust personal identification capabilities [37] [4].

Background: DIP Markers in Forensic Genetics

Technological Advantages of DIP Systems

DIP markers offer several distinct advantages that position them as valuable tools in modern forensic genetics. Unlike STRs, which exhibit stutter artifacts that complicate mixture interpretation, DIPs generate clean electrophoretograms that enhance typing accuracy [37]. Their biallelic nature simplifies analysis while their mutation rate is significantly lower than that of STRs, ensuring greater stability across generations [37]. Furthermore, DIP amplification can be achieved with shorter amplicons (typically <200 bp), making them superior for processing degraded DNA samples commonly encountered in forensic casework [37] [38].

The forensic community has developed various compound marker systems to address specific analytical challenges. DIP-STR markers, which combine slow-evolving DIPs with fast-evolving STRs, have shown exceptional utility for detecting minor contributors in highly imbalanced two-person mixtures [39]. Similarly, multi-InDel markers (haplotypes comprising two or more closely linked DIPs within 200 bp) enhance informativeness while retaining the advantages of small amplicon sizes [38]. These sophisticated approaches demonstrate the evolving application of DIP-based systems in forensic genetics.

Population Genetics Context