Transposing the Conditional: A Forensic Fallacy and Its Critical Implications for Scientific Evidence

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the 'transposing the conditional' fallacy, a critical reasoning error prevalent in the interpretation of forensic and scientific evidence.

Transposing the Conditional: A Forensic Fallacy and Its Critical Implications for Scientific Evidence

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the 'transposing the conditional' fallacy, a critical reasoning error prevalent in the interpretation of forensic and scientific evidence. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and legal professionals, it explores the foundational cognitive psychology behind the fallacy, its manifestation as the Prosecutor's Fallacy, and its profound consequences in legal and clinical settings. The content details modern methodological solutions like Likelihood Ratios, presents structured frameworks for troubleshooting and mitigating cognitive bias, and validates these approaches through comparative analysis of reporting standards and juror comprehension studies. The synthesis offers actionable strategies to enhance the accuracy and integrity of evidence-based decision-making.

The Psychology of Error: Deconstructing the Transposed Conditional

This guide provides technical support for researchers and forensic science professionals working on the "transposing the conditional" fallacy, a fundamental error in interpreting probabilistic evidence. This fallacy, also known as the Prosecutor's Fallacy, occurs when one mistakenly assumes that the probability of the evidence given a hypothesis, P(E|H), is equal to the probability of the hypothesis given the evidence, P(H|E) [1] [2]. In legal contexts, this can lead to severe miscarriages of justice by dramatically overstating the strength of evidence against a defendant [2].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What exactly is the "Transposing the Conditional" fallacy in forensic science?

It is a logical error where P(E|H) and P(H|E) are incorrectly treated as equivalent [1]. For example, a prosecutor might argue that if the probability of finding a DNA match given the defendant is innocent (P(E|I)) is very low (e.g., 1 in a million), then the probability of the defendant's innocence given the DNA match (P(I|E)) must also be 1 in a million. This reasoning is mathematically invalid and ignores the prior probability of the hypothesis (the base rate of innocence in the relevant population) [1] [3].

Q2: What is the real-world impact of this fallacy?

The impact can be catastrophic. In the Sally Clark case (1998), a medical expert testified that the probability of two children in an affluent family dying from Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS) was 1 in 73 million [2]. The court misinterpreted this P(E|I) as the probability of Clark's innocence P(I|E), leading to her wrongful conviction for murder. She was later exonerated but died tragically years after her release [2]. This case underscores the critical need for proper probabilistic reasoning in court.

Q3: How can this fallacy be avoided in practice?

The definitive method to avoid this fallacy is to use Bayes' Theorem, which provides the correct formula to update the probability of a hypothesis given new evidence [1] [3]. The formula is: P(H|E) = [P(E|H) × P(H)] / P(E) Where:

- P(H|E) is the posterior probability (the probability of the hypothesis given the evidence).

- P(E|H) is the likelihood (the probability of the evidence given the hypothesis).

- P(H) is the prior probability (the initial probability of the hypothesis before seeing the evidence).

- P(E) is the marginal probability of the evidence [3].

Q4: Are experts immune to this cognitive bias?

No. Research by cognitive neuroscientist Itiel Dror identifies the "expert immunity fallacy"—the mistaken belief that expertise alone shields a professional from cognitive biases [4]. In reality, the complex and subjective nature of forensic mental health evaluations, for instance, makes experts more vulnerable to cognitive biases, which can infiltrate data collection and interpretation [4].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Misinterpreting Statistical Evidence in a Legal Context

Symptoms: Concluding that a low probability of the evidence under the assumption of innocence (e.g., a random DNA match) directly translates to a low probability of innocence.

Solution: Apply a Bayesian Framework.

- Define the Prior Probability, P(H). In a legal context, this is the initial probability of guilt or innocence before the new evidence is considered. For a DNA match, a neutral prior for innocence might be based on the population of potential suspects [1].

- Determine the Likelihood, P(E|H). This value is often provided by a subject-matter expert, such as a DNA analyst. For example, the probability that an innocent person's DNA would match the crime scene sample might be 1 in 10,000, so P(E|I) = 0.0001 [1].

- Calculate the Posterior Probability, P(H|E). Use Bayes' Theorem to compute the actual probability of the hypothesis (e.g., innocence) given the evidence. Specialized Bayesian software tools (e.g., AgenaRisk) can perform this calculation automatically once the inputs are supplied [1].

Table: Bayesian Analysis of a DNA Match (Assuming a City of 1 Million Potential Suspects)

| Description | Probability | Numerical Value |

|---|---|---|

| Prior Probability of Innocence (P(I)) | (Population - 1) / Population | 999,999 / 1,000,000 ≈ 0.999999 |

| Prior Probability of Guilt (P(G)) | 1 / Population | 1 / 1,000,000 = 0.000001 |

| Probability of Match if Innocent (P(E|I)) | Random match probability | 0.0001 |

| Probability of Match if Guilty (P(E|G)) | Assumed | 1 |

| Posterior Probability of Guilt (P(G|E)) | Calculated via Bayes' Theorem | ≈ 0.0099 (or ~1%) |

The result shows that even with a DNA match with a 1 in 10,000 random match probability, the probability the defendant is guilty is only about 1%, given a neutral prior from a large population. This starkly contrasts with the fallacious intuition that the probability of guilt is 99.99%.

Problem: Mitigating Cognitive Biases in Expert Evaluations

Symptoms: Contextual information, personal expectations, or heuristics (mental shortcuts) unconsciously influencing the collection, weighting, or interpretation of forensic data [4].

Solution: Implement Structured Protocols like Linear Sequential Unmasking-Expanded (LSU-E) [4].

- Blind the Examiner: Initially, the expert should analyze evidence without exposure to potentially biasing contextual information (e.g., knowing which side requested the analysis or details of the suspect's confession) [4].

- Linear Sequential Unmasking: Information should be revealed to the expert in a structured, sequential manner. The examiner must document their findings at each step before receiving the next piece of information. This prevents initial impressions from unduly influencing the entire analysis [4].

- Differential Diagnosis Generation: Actively generate and consider multiple competing hypotheses (e.g., "death by SIDS" vs. "death by murder") before forming a final conclusion. This counters confirmation bias [4].

- Transparent Reporting: The final report should clearly separate factual findings from interpretive opinions and explicitly state all hypotheses that were considered and why some were rejected [4].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol: Applying Bayesian Reasoning to Forensic Evidence

Objective: To quantitatively evaluate the probative value of a piece of forensic evidence while avoiding the transpositional fallacy.

Materials:

- The piece of evidence to be evaluated (E).

- The competing hypotheses (Prosecution, Hp; Defense, Hd).

- Relevant population data for establishing prior probabilities.

Methodology:

- Hypothesis Definition: Clearly state the two competing hypotheses (e.g., Hp: "The defendant is the source of the DNA," Hd: "The DNA comes from an unrelated person in the population").

- Establish Priors: Define a prior probability for each hypothesis. A neutral starting point is often 0.5 for each, or a prior can be based on other, non-biasing evidence.

- Calculate Likelihoods: For each hypothesis, determine the probability of observing the evidence if that hypothesis were true. This is typically provided by a domain expert.

- P(E|Hp): The probability of the evidence if the prosecution's hypothesis is true.

- P(E|Hd): The probability of the evidence if the defense's hypothesis is true.

- Compute the Likelihood Ratio (LR): The LR measures the strength of the evidence.

- LR = P(E|Hp) / P(E|Hd) [5].

- An LR > 1 supports the prosecution's hypothesis; an LR < 1 supports the defense's hypothesis.

- Apply Bayes' Theorem: Update the prior odds of the hypothesis using the LR to obtain the posterior odds.

- Posterior Odds = LR × Prior Odds [5].

Protocol: Cognitive Bias Mitigation for Expert Analysis

Objective: To minimize the influence of cognitive biases during the evidence analysis phase.

Materials: Case evidence, standard evaluation tools, and a structured reporting form.

Methodology (Linear Sequential Unmasking-Expanded):

- Initial Blind Analysis: The examiner performs an initial assessment of the core evidence (e.g., a fingerprint, a medical scan) without any contextual information about the case.

- Documentation of Preliminary Findings: The results, confidence level, and potential alternative interpretations from the blind analysis are recorded.

- Controlled Information Revelation: The examiner is given access to case information in a pre-determined, sequential order (e.g., first the police report, then the suspect's profile).

- Re-assessment and Documentation: After each new piece of information is revealed, the examiner re-assesses the evidence and documents any changes to their conclusions and the rationale for the change.

- Hypothesis Generation and Testing: The examiner is required to explicitly list at least two alternative hypotheses that could explain the evidence and evaluate the evidence against each.

- Peer Review: The entire process and findings are reviewed by a second, independent expert who is also blinded to the initial examiner's conclusion.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table: Essential Conceptual "Tools" for Research on the Conditional Probability Fallacy

| Tool / Concept | Function / Explanation | Relevance to Research |

|---|---|---|

| Bayes' Theorem | The mathematical formula for updating the probability of a hypothesis given new evidence. P(H|E) = [P(E|H) × P(H)] / P(E) [3]. | The foundational framework for correctly interpreting probabilistic evidence and avoiding the fallacy. |

| Likelihood Ratio (LR) | A measure of the strength of evidence, calculated as P(E|Hp) / P(E|Hd) [5]. | Provides a standardized, balanced way for experts to present the value of their findings without committing the fallacy. |

| Prior Probability (P(H)) | The initial probability of a hypothesis before new evidence is considered [1] [3]. | A critical, though often contentious, component of Bayesian analysis. Research must address how to establish defensible priors in legal settings. |

| Cognitive Bias Mitigation (e.g., LSU-E) | Structured protocols designed to minimize the unconscious influence of context and heuristics on expert judgment [4]. | Provides an experimental methodology for studying how biases arise and can be controlled in forensic decision-making. |

| System 1 vs. System 2 Thinking | A framework for understanding human cognition. System 1 is fast, intuitive, and error-prone (source of the fallacy). System 2 is slow, analytical, and logical (required for correct reasoning) [4] [5]. | Explains the psychological roots of the fallacy and underscores why deliberate, trained analytical thinking is necessary to overcome it. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges in Studying Heuristics

When conducting experiments on cognitive heuristics, researchers often encounter specific issues that can compromise data integrity. The following table outlines common problems and their solutions.

| Problem | Description & Impact | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low CRT Engagement | Participants quickly give intuitive (incorrect) answers on the Cognitive Reflection Test (CRT), failing to engage analytical System 2 thinking [6]. | - Use the three-item CRT (Bat & Ball, Widgets, Lily Pad) [6].- Ensure participants are not HALT (Hungry, Angry, Late, or Tired) [6].- Analyze response patterns; a decrease in intuitive answers from Q1 to Q3 indicates improving engagement [6]. |

| Prosecutor's Fallacy in Data Interpretation | Mistaking the probability of the evidence given innocence (P(E|Hd)) for the probability of innocence given the evidence (P(Hd|E)), leading to profound errors in interpreting forensic or diagnostic test results [7] [8]. | - Use Likelihood Ratios (LR) to report strength of evidence: LR = P(E|Hp) / P(E|Hd) [8].- Frame results within the context of base rates (prior probability).- For diagnostic tests, use 2x2 tables to visually distinguish false positive rates from the probability of no disease given a positive result [7]. |

| Anchoring Bias in Experimental Design | The initial information presented (the "anchor") biases subsequent numerical estimates made by participants, skewing results [9] [10]. | - In control groups, use irrelevant and extreme numerical anchors (e.g., 100,000 vs. 10,000) to demonstrate the effect [10].- Blind participants to potential anchors during the estimation phase of the experiment.- Use between-subjects designs to test the effects of different anchors. |

| Misapplication of the Linda Problem | The conjunction fallacy (judging "feminist bank teller" as more likely than "bank teller") is interpreted solely as a System 1 error, ignoring potential linguistic implicatures [9]. | - When using the Linda problem, include debriefing questions to understand participant reasoning.- Consider that participants may add an unstated "exclusive or" cultural implicature [9]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the practical differences between System 1 and System 2 thinking in a research context?

System 1 and System 2 are two distinct modes of cognitive operation [9] [11].

- System 1 is fast, automatic, effortless, and intuitive. It operates based on heuristics (mental shortcuts) and is prone to cognitive biases. Examples include understanding simple sentences or driving a car on an empty road [9].

- System 2 is slow, deliberate, effortful, and analytical. It is logical and calculating but requires conscious energy. Examples include checking the validity of a complex logical argument or parking in a tight space [9]. In research, tasks like the Cognitive Reflection Test (CRT) are designed to pit these systems against each other. An intuitive, incorrect answer is attributed to System 1, while a correct, deliberative answer is attributed to successful intervention by System 2 [6].

Q2: How can we prevent the Prosecutor's Fallacy when presenting statistical evidence, such as DNA match probabilities?

The key is to avoid stating or implying that the random match probability (RMP) is the probability of the defendant's innocence. The RMP is P(Match | Innocent), not P(Innocent | Match) [7] [8]. The recommended modern approach is to use a Likelihood Ratio (LR). The LR quantitatively expresses how much more likely the evidence is under the prosecution's hypothesis (Hp: "The suspect is the source") compared to the defense's hypothesis (Hd: "A random person is the source") [8]. The formula is: LR = P(Evidence | Hp) / P(Evidence | Hd). This LR can then be combined with the prior odds (based on all other evidence) using Bayes' Theorem to update the belief about the hypotheses. This method keeps the expert's testimony within their domain and avoids the fallacious transposition of conditional probabilities [8].

Q3: Our studies show that experts sometimes make intuitive, correct decisions. Does this contradict the error-prone nature of System 1?

No, it does not. While System 1 can be error-prone, particularly in novel situations or with statistical reasoning, it is also an indispensable tool for experts [12] [6]. Complex cognitive operations, such as a chess master's move or a doctor's pattern recognition, migrate from effortful System 2 to automatic System 1 as proficiency is acquired [9] [6]. The accuracy of an intuitive decision often depends on the decision-maker's confidence grounded in relevant expertise and experience [12]. Therefore, intuitive System 1 thinking is not inherently flawed; its reliability is context-dependent and enhanced by pattern recognition built through extensive practice.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol: Eliciting and Measuring the Anchoring Heuristic

Objective: To demonstrate how an irrelevant number can systematically bias numerical estimates. Materials: Two versions of a questionnaire (Version A with a high anchor, Version B with a low anchor). Procedure:

- Participant Grouping: Randomly assign participants to Group A or Group B.

- Anchoring Manipulation:

- Group A (High Anchor): Ask participants: "Is the average price of German cars higher or lower than €100,000?" Then ask: "What is your best estimate of the average price of German cars?" [10].

- Group B (Low Anchor): Ask participants: "Is the average price of German cars higher or lower than €10,000?" Then ask for their estimate [10].

- Data Collection: Collect all estimates. Analysis: Compare the mean estimates between Group A and Group B using a t-test. A statistically significant difference confirms the anchoring effect, with Group A's estimates expected to be significantly higher than Group B's [10].

Protocol: The Cognitive Reflection Test (CRT)

Objective: To assess an individual's tendency to override an intuitive (System 1) response and engage in deliberate (System 2) reasoning [6]. Materials: The three-item CRT. Procedure:

- Administer the following three questions, ensuring participants have sufficient time (10-15 minutes is typical) [6]:

- Q1 (Bat and Ball): "A bat and a ball cost $1.10 in total. The bat costs $1.00 more than the ball. How much does the ball cost?" (Intuitive answer: 10 cents. Correct answer: 5 cents).

- Q2 (Widgets): "If it takes 5 machines 5 minutes to make 5 widgets, how long would it take 100 machines to make 100 widgets?" (Intuitive answer: 100 minutes. Correct answer: 5 minutes).

- Q3 (Lily Pad): "In a lake, there is a patch of lily pads. Every day, the patch doubles in size. If it takes 48 days for the patch to cover the entire lake, how long would it take for the patch to cover half of the lake?" (Intuitive answer: 24 days. Correct answer: 47 days) [6].

- Data Coding: Code responses as "intuitive" (the incorrect answer listed above), "analytical" (correct answer), or "other" (any other incorrect answer) [6]. Analysis: Calculate the percentage of participants who give intuitive vs. analytical answers for each question. It is common to observe a reduction in intuitive answers as participants progress from Q1 to Q3 [6].

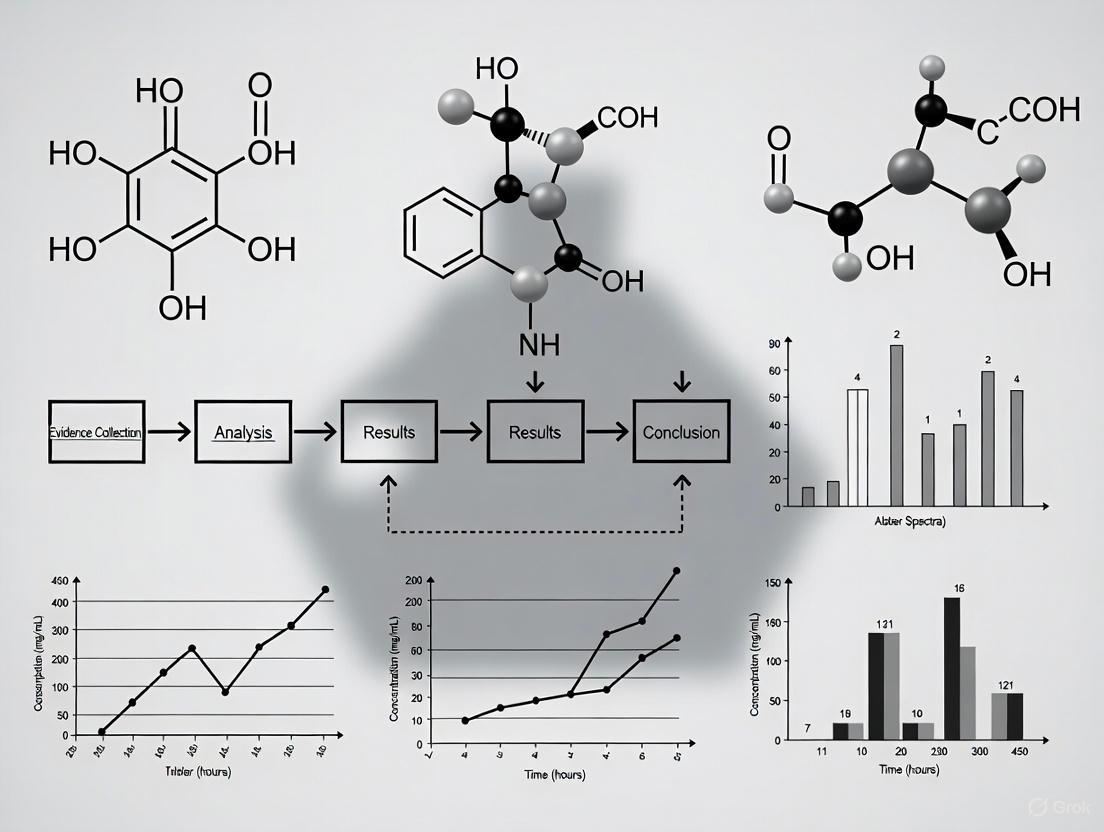

Visualizing Logical Relationships

The Prosecutor's Fallacy: A Logical Breakdown

Correct Evidence Interpretation with Likelihood Ratios

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Cognitive Reflection Test (CRT) | A three-question tool designed to measure the ability to inhibit an intuitive (System 1) response and engage in analytical (System 2) reasoning. Used as a baseline for assessing cognitive style in judgment and decision-making experiments [6]. |

| Base Rate Scenarios | Experimental vignettes that include information about population prevalence (base rate) and specific case information. Used to study the base rate neglect fallacy, where individuals ignore the prior probability in favor of individuating information [7]. |

| Likelihood Ratio (LR) Framework | A statistical methodology for quantifying the strength of forensic evidence. It prevents the Prosecutor's Fallacy by keeping the expert's testimony within the bounds of the evidence itself (P(E|H)), without making claims about the ultimate issue (guilt or innocence) [8]. |

| "Linda Problem" (Conjunction Fallacy) | A classic scenario demonstrating the conjunction fallacy, where participants judge a conjunction (e.g., "feminist bank teller") as more probable than one of its constituents ("bank teller"), often due to System 1's substitution of a easier question about representativeness [9]. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Common Research Fallacies

FAQ: What is the "transposed conditional" and how can I avoid it in my research?

Q: I've heard that misapplying statistics is a common source of error in forensic science. What exactly is the "transposed conditional" and how can I identify and avoid it in my research?

A: The transposed conditional, often called the prosecutor's fallacy, occurs when the conditional probability of A given B is mistakenly interpreted as the probability of B given A. In forensic contexts, this often manifests as incorrectly equating the probability of finding evidence if the defendant is innocent with the probability of innocence given the evidence. To avoid this, researchers should adopt a Bayesian framework using likelihood ratios, which properly compares the probability of the evidence under competing propositions (e.g., prosecution vs. defense hypotheses) rather than making definitive statements about guilt or innocence [13].

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying Statistical Misapplication

Problem: Statistical evidence is being presented in a way that may mislead fact-finders about the strength of forensic evidence.

Diagnosis: This often occurs when:

- Conditional probabilities are presented without proper context

- Base rates are ignored or misunderstood

- Statistics are presented as definitive proof rather than one piece of evidence

Solution: Apply this systematic troubleshooting approach:

Understand the Problem: Clearly define the statistical question being asked. What exactly does this probability represent? [13]

Isolate the Issue: Identify where the conditional probability may have been transposed. Ask: "Is this the probability of the evidence given a hypothesis, or the probability of the hypothesis given the evidence?" [13]

Find a Fix: Implement Bayesian framework using likelihood ratios to properly express the probative value of evidence [13].

Verification Checklist:

- Have I clearly distinguished between P(E|H) and P(H|E)?

- Have I considered the base rate of the phenomenon?

- Have I used likelihood ratios to express evidential strength?

- Have I contextualized statistical evidence within the entire body of evidence?

Case Study Analysis: Quantitative Data Comparison

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Miscarriage of Justice Cases

| Case Aspect | Sally Clark | Lucy Letby |

|---|---|---|

| Years in Prison | 3.0 [14] | Serving whole-life term [15] |

| Initial Conviction Year | 1999 [14] | 2023 (trials concluded) [15] |

| Conviction Overturned | 2003 [14] | Under review by CCRC (as of 2025) [16] |

| Key Statistical Error | 1 in 73 million probability of two cot deaths presented [17] | Statistical association of presence with incidents [15] |

| Medical Evidence Issues | Non-disclosure of microbiological report showing infection [18] | Dispute over interpretation of air embolism evidence [15] |

| Appeal Status | Successful on second appeal [14] | Two failed appeals; CCRC review pending [15] [16] |

| Primary Fresh Evidence | Bacteriological evidence of infection not disclosed at trial [18] | International expert panel challenging medical conclusions [15] |

Table 2: Statistical Error Analysis in Forensic Cases

| Error Type | Case Example | Consequence | Proper Methodological Alternative |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transposed Conditional | Misinterpretation of probability of two SIDS deaths in Sally Clark case [17] | Jury potentially misled about significance of statistical evidence [17] | Bayesian likelihood ratio framework [13] |

| Ignoring Base Rates | Media focus on rarity of two cot deaths without context [17] | Created perception of near-certain guilt [17] | Consider population prevalence and alternative explanations |

| Evidence Misapplication | Use of 1989 air embolism research in Lucy Letby case [15] | Potential misinterpretation of diagnostic criteria [15] | Contextual application of research with clear limitations |

| Non-Disclosure | Failure to share microbiological evidence in Clark case [18] | Deprived defense of potentially exculpatory evidence [18] | Full transparency in evidence sharing |

Experimental Protocols: Forensic Evidence Validation

Protocol 1: Bayesian Likelihood Ratio Calculation for Forensic Evidence

Purpose: To properly evaluate the strength of forensic evidence while avoiding transposed conditional fallacy.

Materials:

- Forensic evidence dataset

- Relevant population statistics

- Computational tools for probability calculation

Methodology:

- Define Competing Hypotheses: Clearly state prosecution (Hp) and defense (Hd) hypotheses.

- Calculate Probability Under Hp: Determine P(E|Hp) - probability of evidence if prosecution hypothesis is true.

- Calculate Probability Under Hd: Determine P(E|Hd) - probability of evidence if defense hypothesis is true.

- Compute Likelihood Ratio: LR = P(E|Hp) / P(E|Hd)

- Interpret Results: LR > 1 supports prosecution; LR < 1 supports defense; LR = 1 evidence has no probative value [13]

Validation Criteria:

- Hypotheses must be mutually exclusive and exhaustive

- Population data must be relevant and representative

- Transparency in all assumptions and data sources

Protocol 2: Systematic Review of Medical Evidence in Suspicious Death Cases

Purpose: To ensure comprehensive evaluation of alternative explanations in suspected homicide cases.

Materials:

- Complete medical records and autopsy reports

- Microbiology and toxicology results

- Expert reviews from multiple relevant specialties

Methodology:

- Blinded Case Review: Experts review materials without knowledge of prosecution/defense alignment.

- Differential Diagnosis: Generate comprehensive list of potential natural and non-natural causes.

- Evidence Weighting: Evaluate strength of evidence for each potential cause.

- Consensus Building: Identify areas of agreement and disagreement among experts.

- Uncertainty Documentation: Clearly document limitations and uncertainties in conclusions.

Application Notes: This protocol addresses issues seen in both Clark (incomplete medical investigation) [18] and Letby (disputed cause of death determinations) [15] cases.

Visualizing Logical Relationships in Forensic Reasoning

Diagram 1: Proper Evidence Interpretation Framework

Proper Evidence Evaluation - Bayesian framework comparing evidence under competing hypotheses.

Diagram 2: Common Fallacy Pathways

Fallacy Pathways - Contrasting proper statistical application with common errors.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Forensic Methodology

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Bayesian Likelihood Ratio Framework | Properly evaluates strength of evidence without transposing conditionals [13] | Calculating probative value of forensic match evidence |

| Differential Diagnosis Protocol | Systematic consideration of alternative explanations | Medical cause of death determination in suspicious cases |

| Evidence Transparency Standards | Ensures full disclosure of all relevant evidence | Preventing non-disclosure issues as in Clark case [18] |

| Expert Blind Review Protocol | Reduces confirmation bias in expert evaluations | Review of contested medical evidence as in Letby case [15] |

| Statistical Base Rate Calculators | Contextualizes rare event probabilities within relevant populations | Proper interpretation of coincidence probabilities |

| Uncertainty Quantification Methods | Clearly communicates limitations in conclusions | Expressing diagnostic uncertainty in complex medical cases |

Advanced Troubleshooting: Complex Research Scenarios

FAQ: How should researchers handle conflicting expert opinions?

Q: In cases like Lucy Letby's, where international expert panels contradict trial experts, how should researchers approach such conflicting testimony?

A: Systematic analysis of conflicting expertise requires:

- Methodology Transparency: Evaluate whether all experts used sound, transparent methodologies.

- Assumption Documentation: Compare underlying assumptions and their validity.

- Evidence Comprehensiveness: Assess whether all relevant evidence was considered.

- Uncertainty Acknowledgement: Prefer experts who appropriately acknowledge limitations.

- Consensus Seeking: Identify points of agreement while properly contextualizing disagreements [15].

Advanced Protocol: Systematic Error Review in Closed Cases

Purpose: To identify potential miscarriages of justice through methodological review.

Methodology:

- Statistical Evidence Audit: Review all statistical presentations for transposed conditionals and base rate neglect.

- Medical Evidence Re-evaluation: Conduct blinded review of medical evidence considering new research.

- Disclosure Compliance Check: Verify all relevant evidence was properly disclosed.

- Contextual Analysis: Evaluate evidence within broader context rather than isolation.

Case Application: This methodology mirrors the approach taken by the CCRC in the Sally Clark case, which identified undisclosed microbiological evidence and statistical misapplication [18].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Identifying and Correcting the Prosecutor's Fallacy in Statistical Evidence

Problem: A DNA test shows a match between a suspect and crime scene evidence. The random match probability is 1 in 1,000,000. A colleague concludes this means there is only a 1 in 1,000,000 chance the suspect is innocent.

Diagnosis: This is a classic example of the Prosecutor's Fallacy. The error lies in transposing the conditional probability [7] [19]. Specifically, your colleague has confused:

P(Match | Innocence)- The probability of observing the DNA match given the suspect is innocent, which is 1/1,000,000.P(Innocence | Match)- The probability the suspect is innocent given the DNA match, which is a very different value [20].

Solution:

- Apply Bayes' Theorem to calculate the correct probability of innocence given the evidence [20] [19]:

P(Innocence | Match) = [P(Match | Innocence) * P(Innocence)] / P(Match) - Account for the prior probability (base rate). For a city of 500,000 people, the prior probability of innocence for a random individual is very high [21].

- Use a Likelihood Ratio (LR) to present the strength of the evidence without committing the fallacy. The LR describes how much more likely the evidence is under the prosecution's hypothesis (guilt) compared to the defense's hypothesis (innocence) [8] [22].

Verification: The following table compares the fallacious reasoning with the correct statistical interpretation using a hypothetical population of 500,000 [23] [21]:

| Statistical Measure | Fallacious Interpretation (Prosecutor's Fallacy) | Correct Interpretation & Calculation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random Match Probability (RMP) | The probability that the suspect is innocent is 1 in 1,000,000. | The probability that an innocent person would match the DNA profile is 1 in 1,000,000. `P(Evidence | Innocence) = 0.000001` [20]. |

| Posterior Probability of Innocence | Not calculated; incorrectly assumed to be equal to the RMP. | Using Bayes' Theorem, the probability of innocence given the match is calculated to be approximately 20% (or 1 in 5) in a large population [21]. |

Guide 2: Debugging Experimental Design to Avoid Base Rate Neglect

Problem: A new forensic test for a specific fiber type has a false positive rate of 1%. During validation, a researcher reports that a positive test result indicates a 99% probability that the fiber is from a suspect's garment.

Diagnosis: The error is base rate neglect—the failure to incorporate the prior probability of the event being tested for (the "base rate") into the final analysis [7]. The 99% figure only reflects the test's accuracy but ignores how rare or common the fiber type is in the general environment.

Solution:

- Determine the base rate (prevalence) of the fiber type in the relevant population or environment.

- Apply Bayes' Theorem to calculate the true probability. A low base rate can drastically reduce the meaning of a positive test result [7] [19].

- Validate with a contingency table to visualize the numbers.

Verification: If the fiber type is present in only 0.1% of garments, a test with a 1% false positive rate yields a surprisingly low true positive rate.

| Fiber is Present (0.1%) | Fiber is Absent (99.9%) | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Test Positive | 1 True Positive | 999 False Positives | 1,000 |

| Test Negative | 0 | 98,901 | 98,901 |

| Total | 1 | 99,900 | 100,000 |

As the table shows, out of every 1,000 positive test results, only 1 is a true positive. Therefore, the probability the fiber is present given a positive test is ~0.1%, not 99% [20]. This logic is critical for validating the real-world performance of any forensic test.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the core logical error in the Prosecutor's Fallacy?

The core error is transposing the conditional probability [7] [19]. It is the mistaken belief that the probability of finding the evidence given the defendant is innocent P(E | I) is the same as the probability the defendant is innocent given the evidence P(I | E). These two probabilities are often vastly different.

How can I present forensic evidence without committing the Prosecutor's Fallacy?

The modern standard is to use the Likelihood Ratio (LR) [8] [22]. The LR characterizes the strength of the evidence without making claims about the ultimate issue of guilt or innocence, which is the jury's role.

LR = P(Evidence | Prosecution Hypothesis) / P(Evidence | Defense Hypothesis)

An LR of 1000 means the evidence is 1000 times more likely if the prosecution's hypothesis is true than if the defense's hypothesis is true. This is a statistically sound way for an expert to present their findings.

Are there real-world cases where this fallacy led to a miscarriage of justice?

Yes, several documented cases exist, with the Sally Clark case being one of the most infamous [7] [23] [2].

- Context: Sally Clark was a British lawyer convicted in 1999 of murdering her two infant sons.

- The Fallacy: An expert witness testified that the probability of two children in an affluent family dying from Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS) was 1 in 73 million. The prosecution argued this meant there was only a 1 in 73 million chance she was innocent.

- The Error: The statistic (1 in 73 million) was

P(Two SIDS deaths | Innocence). The fallacy was interpreting it asP(Innocence | Two SIDS deaths). The calculation also wrongly assumed the two deaths were independent events, ignoring potential genetic or environmental links [23] [2]. - Outcome: Sally Clark's conviction was overturned on appeal, but she tragically died a few years later from alcohol poisoning.

What is the "Defense Attorney's Fallacy"?

While the Prosecutor's Fallacy overvalues the strength of evidence, the Defense Attorney's Fallacy undervalues it [23]. For example, if a DNA profile has a random match probability of 1 in 1,000,000 in a city of 500,000 people, a defense attorney might fallaciously argue that since several people in the city would be expected to match, the evidence is meaningless. This ignores the fact that the suspect was identified for reasons other than the DNA search, making the match highly significant. The probability that a specific individual, initially identified through other evidence, would match by chance remains 1 in 1,000,000.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials for Robust Forensic Statistics

| Item | Function & Explanation |

|---|---|

| Bayes' Theorem | A fundamental formula for updating the probability of a hypothesis (e.g., guilt) based on new evidence. It is the primary antidote to the Prosecutor's Fallacy as it correctly incorporates prior probability and the strength of new evidence [20] [19]. |

| Likelihood Ratio (LR) | The recommended modern framework for forensic experts to report the strength of their findings. It allows experts to stay within their domain by commenting on the evidence without directly opining on the ultimate issue of guilt, which requires considering the prior odds [8]. |

| Base Rate Data | The background prevalence of a characteristic (e.g., a DNA profile, a fiber type, a disease) in a relevant population. This data is a critical input for Bayes' Theorem and prevents base rate neglect [7] [19]. |

| Population Database | A collection of genetic or other forensic data from a reference population. It is used to estimate the random match probability for a given piece of evidence, which forms the denominator of the likelihood ratio for many types of forensic evidence [22]. |

Visualizing the Logical Flow of the Prosecutor's Fallacy

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships and error in reasoning that constitute the Prosecutor's Fallacy.

Diagram 1: The Logic of Transposing the Conditional

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How can I change the font color for only a specific part of a node's label in Graphviz?

A1: Use HTML-like labels. Standard Graphviz labels do not allow formatting of individual text sections. Enclose the label within < > and use the <FONT> tag to specify attributes like COLOR for specific text parts [24].

Example:

Q2: My Graphviz output is not generating, or I get a decoding error when using it with Python. What should I do?

A2: This often indicates an installation or path issue [25].

- Verify Installation: Ensure Graphviz is installed on your system and that the

dotcommand works in your terminal. - Check Python Environment: Reconfigure your environment variables to ensure Python can find the Graphviz binaries [25].

- Try Alternative Formats: If rendering to one format (e.g., PNG) fails, try another (e.g., SVG or PDF) to isolate the problem [25].

Q3: How do I ensure sufficient color contrast for text within shapes (nodes) in my diagram?

A3: Explicitly set the fontcolor attribute for any node where you also specify a fillcolor [26]. Do not rely on default colors. Use a color contrast checker to ensure readability. For example, use a dark fontcolor on a light fillcolor and vice-versa.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Resolving Common Graphviz Rendering Issues

Problem: Diagram fails to render or view correctly.

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| "Warning: Not built with libexpat" or HTML-like labels not working [24]. | Using an old or limited Graphviz engine (e.g., Viz.js). | Install the latest Graphviz on your computer or use a modern web-based editor like the Graphviz Visual Editor [24]. |

| UnicodeDecodeError when using Python's Graphviz library [25]. | Path conflict or installation issue. | Reinstall Graphviz, ensure it's added to your system's PATH during installation [24], and verify the connection between the Python library and the Graphviz executable [25]. |

| Diagram is too large or runs off the canvas [24]. | Layout is too spread out. | Adjust graph attributes like nodesep (space between nodes) and ranksep (space between ranks). Use the size attribute to control the overall drawing size [27]. |

Guide 2: Troubleshooting Experimental Reagent Contamination

Problem: Inconsistent or erroneous results in immunoassay detection.

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Check Reagent Integrity: Inspect antibody and enzyme conjugate containers for cracks. Verify storage temperatures. | All reagents are physically intact and have been stored at recommended temperatures. |

| 2 | Run Positive Control: Use a known positive sample with the suspected contaminated reagent lot. | The positive control yields a clear, expected signal. A weak or absent signal suggests reagent degradation. |

| 3 | Perform Cross-Test: Use the suspected reagent with a different set of known-good reagents from a separate lot. | The test performs as expected, isolating the fault to a specific reagent component. |

| 4 | Confirm with Fresh Reagents: Repeat the original failed experiment with a new, unopened set of reagents. | The experiment produces the correct, expected result, confirming the initial reagent was the source of contamination. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard Workflow for Diagnostic ELISA

Principle: This protocol details the steps for a standard Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) to detect a specific antigen in a patient serum sample, forming a basis for discussing diagnostic validity.

Methodology:

- Coating: Coat a 96-well microtiter plate with a capture antibody specific to the target antigen. Incubate overnight at 4°C.

- Blocking: Wash the plate with PBS-Tween (a buffer with a detergent) and block remaining protein-binding sites with a protein-based buffer (e.g., 5% BSA in PBS) for 1-2 hours at room temperature.

- Sample Incubation: Add the patient serum samples and positive/negative controls to the designated wells. Incubate for 1-2 hours to allow antigen-antibody binding.

- Detection Antibody Incubation: Wash the plate to remove unbound material. Add a biotinylated detection antibody specific to a different epitope of the antigen. Incubate.

- Enzyme Conjugate Incubation: Wash again. Add a streptavidin-Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) conjugate. Incubate.

- Substrate Addition & Signal Detection: Wash thoroughly. Add a chromogenic HRP substrate (e.g., TMB). The enzyme converts the substrate, producing a color change.

- Stop and Read: Add a stop solution (e.g., sulfuric acid) and immediately measure the absorbance (Optical Density) with a plate reader at the appropriate wavelength (e.g., 450nm for TMB).

Protocol 2: Western Blot Analysis for Protein Validation

Principle: This protocol describes the process of separating proteins by molecular weight and detecting a specific protein with antibodies, commonly used to confirm the identity of a biomarker.

Methodology:

- Protein Extraction and Quantification: Lyse cells or tissue to extract proteins. Quantify the total protein concentration using an assay like BCA or Bradford.

- Gel Electrophoresis: Load equal amounts of protein into wells of an SDS-PAGE gel. Apply an electric current to separate proteins by size.

- Protein Transfer: Transfer the separated proteins from the gel onto a nitrocellulose or PVDF membrane.

- Blocking: Incubate the membrane in a blocking buffer (e.g., 5% non-fat dry milk) to prevent non-specific antibody binding.

- Primary Antibody Incubation: Incubate the membrane with a primary antibody specific to the protein of interest. Wash to remove unbound antibody.

- Secondary Antibody Incubation: Incubate the membrane with an enzyme-conjugated secondary antibody (e.g., HRP-anti-mouse) that binds to the primary antibody. Wash again.

- Signal Detection: Incubate the membrane with a chemiluminescent substrate for HRP. Expose the membrane to X-ray film or image in a digital imager to visualize the protein bands.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparison of Key Biomarker Detection Assays

| Assay Type | Principle | Detection Limit | Throughput | Key Quantitative Data (e.g., CV%) | Common Pitfalls (Transposing the Conditional Link) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ELISA | Antibody-antigen binding with enzyme-linked colorimetric detection. | ~pg/mL | High | Intra-assay CV: <10%; Inter-assay CV: <15% | Interpreting a positive test as definitive proof of disease confuses P(Result|Disease) with P(Disease|Result). |

| Western Blot | Protein separation by size, followed by immunodetection. | ~ng | Low | Not inherently quantitative; semi-quantitative via densitometry. | Reporting a band of correct molecular weight as conclusive evidence of a specific protein, ignoring other cross-reactive proteins. |

| PCR (qRT-PCR) | Amplification of specific DNA/RNA sequences with fluorescent probes. | ~10-100 copies | High | Efficiency: 90-110%; R² > 0.98 | Equating the presence of viral DNA with active, transmissible infection, a fallacy of misapplied conditionals. |

| Immunohistochemistry (IHC) | Microscopic localization of antigens in tissue sections using labeled antibodies. | N/A (qualitative/semi-quantitative) | Medium | Scoring is subjective (e.g., H-score, Allred score) | Misdiagnosis based on antibody cross-reactivity with normal tissue antigens, a form of ignoring the false positive rate. |

Diagrammatic Visualizations

Experimental Workflow

Conditional Logic in Diagnostics

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Materials for a Featured ELISA Experiment

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Capture Antibody | The primary antibody that binds and immobilizes the target antigen onto the microtiter plate. |

| Biotinylated Detection Antibody | A secondary antibody that binds a different epitope on the captured antigen; conjugated to biotin for signal amplification. |

| Streptavidin-HRP Conjugate | An enzyme complex that binds with high affinity to biotin, enabling a colorimetric reaction for detection. |

| Chromogenic Substrate (TMB) | A colorless solution that, when catalyzed by HRP, produces a blue product, measurable via absorbance. |

| Blocking Buffer (e.g., BSA) | A protein solution used to cover any unsaturated binding sites on the plate to prevent non-specific antibody binding. |

| Wash Buffer (PBS-Tween) | A buffered saline solution with a detergent (Tween-20) used to remove unbound reagents between steps, reducing background noise. |

A Framework for Accuracy: Implementing Likelihood Ratios and Bayesian Reasoning

The Likelihood Ratio (LR) as the Gold Standard for Evidential Weight

The Likelihood Ratio (LR) is a fundamental statistical measure for quantifying the strength of forensic evidence. It compares the probability of observing the evidence under two competing hypotheses: the prosecution's proposition ((Hp)) and the defense's proposition ((Hd)) [28] [8]. The LR provides a balanced and transparent method for experts to communicate their findings without infringing on the court's responsibilities, thereby helping to avoid logical fallacies such as the transposition of the conditional (also known as the Prosecutor's Fallacy) [8] [29].

The core definition of the LR is: LR = P(E | Hp) / P(E | Hd) Where:

- P(E | H_p) is the probability of observing the evidence (E) if the prosecution's hypothesis is true.

- P(E | H_d) is the probability of observing the evidence (E) if the defense's hypothesis is true [28] [22].

Interpreting the Likelihood Ratio Value:

- LR > 1: The evidence supports the prosecution's proposition ((H_p)).

- LR = 1: The evidence is neutral; it supports neither proposition.

- LR < 1: The evidence supports the defense's proposition ((H_d)) [28].

TABLE: Likelihood Ratio Verbal Equivalents [28]

| LR Value Range | Verbal Equivalent |

|---|---|

| 1 - 10 | Limited evidence to support H_p |

| 10 - 100 | Moderate evidence to support H_p |

| 100 - 1,000 | Moderately strong evidence to support H_p |

| 1,000 - 10,000 | Strong evidence to support H_p |

| > 10,000 | Very strong evidence to support H_p |

Core Concepts and Definitions

The Role of the LR in the Bayesian Framework

The Likelihood Ratio is the engine for updating beliefs within a Bayesian framework. It allows a decision-maker (e.g., a judge or juror) to update their prior beliefs about a case based on new forensic evidence [8] [30].

The process is formally expressed using the odds form of Bayes' rule: Posterior Odds = Likelihood Ratio × Prior Odds [8] [30]

Where:

- Prior Odds: The initial odds of the hypotheses (e.g., (Hp) vs. (Hd)) based on all non-forensic evidence.

- Likelihood Ratio: The strength of the forensic evidence as provided by the expert.

- Posterior Odds: The updated odds of the hypotheses after considering the forensic evidence.

This framework clearly delineates the roles of the participants: the expert provides the LR, while the court assesses the prior odds to determine the posterior odds [8].

Contrasting the LR with Other Metrics

It is critical to distinguish the LR from other statistical measures that are often confused or misused.

Likelihood Ratio vs. Posterior Probability:

- The LR is the probability of the evidence given the hypotheses. This is the proper domain of the forensic expert.

- The Posterior Probability is the probability of the hypotheses given the evidence. This requires combining the LR with prior odds and is the ultimate task of the court [8] [29].

Likelihood Ratio vs. Random Match Probability (RMP):

- In a simple case involving a single-source DNA profile, the LR is the reciprocal of the Random Match Probability (LR = 1/RMP) [22].

- The RMP estimates the probability that a randomly selected person from the population would match the evidence profile. While related, the LR is a more versatile and foundational concept that can be applied to complex evidence beyond simple matches.

Common Issues and Troubleshooting Guide

This section addresses specific challenges researchers and practitioners may encounter when implementing the LR framework.

TABLE: Troubleshooting Common LR Implementation Issues

| Problem | Description & Consequences | Solution / Correct Approach |

|---|---|---|

| The Prosecutor's Fallacy [7] [8] [29] | Mistaking P(E|Hp) for P(Hp|E). Example: Stating "The chance this DNA match is false is 1 in a million" when the LR is 1,000,000. This is a logical error that can lead to miscarriages of justice. | Experts must report on the probability of the evidence, not the probability of the hypothesis. Correct wording: "The evidence is 1,000,000 times more likely if the suspect is the source than if an unrelated random person is the source." |

| Ignoring Prior Odds (Base Rate Neglect) [7] [8] | Presenting a high LR as definitive proof of guilt without considering the prior likelihood of guilt based on other case evidence. | Recognize that the LR is only one part of the equation. A high LR may not lead to a high posterior probability if the prior odds are very low. |

| Uncertainty in LR Calculation [30] | The calculated LR value can be sensitive to the choice of statistical models, population databases, and underlying assumptions. Presenting a single LR value can mask this uncertainty. | Conduct and communicate an uncertainty analysis. Use a "lattice of assumptions" to explore how the LR changes under different reasonable models and report a range of plausible values. |

| Communicating the LR to Lay Audiences [8] [29] | Judges and juries may find numerical LRs difficult to interpret, potentially leading to misunderstanding or undervaluing the evidence. | Use verbal equivalent scales (see Table 1) as a guide alongside the numerical LR. Ensure expert witnesses are trained in clear communication to explain the meaning of the LR without falling into fallacious reasoning. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is the LR considered the "gold standard" for expressing evidential weight? The LR is considered the gold standard because it is:

- Transparent: It forces explicit statement of the propositions being compared.

- Balanced: It fairly assesses the evidence under both the prosecution and defense hypotheses.

- Theoretically Sound: It is rooted in Bayesian logic, the normative framework for updating beliefs with new evidence.

- Versatile: It can be applied to virtually any type of forensic evidence, from DNA to fingerprints [8] [30].

Q2: How do I avoid the Prosecutor's Fallacy when testifying about an LR? The key is to always frame the statement around the probability of the evidence. Before testifying, check your statement:

- Fallacious Statement: "This match means there is only a one-in-a-billion chance the suspect is not the source." (This is P(H_d|E)).

- Correct Statement: "The observed match is one billion times more likely if the suspect is the source than if a randomly selected person is the source." (This is P(E|Hp) / P(E|Hd)) [8] [29].

Q3: My LR calculation depends on the population database I use. Is this a problem? This is a common issue that highlights the need for uncertainty characterization. The choice of a population database is one of many assumptions in the "lattice of assumptions" that underpin your model. It is not inherently a problem, but it should be acknowledged. Best practice involves:

- Using well-established, relevant population databases.

- Testing the sensitivity of your LR to different reasonable database choices.

- Reporting the potential range of LRs, or at a minimum, discussing the assumptions and potential sources of uncertainty in your report [22] [30].

Q4: Can the LR framework be applied to complex DNA mixtures? Yes. While the calculation for complex mixtures requires sophisticated probabilistic genotyping software (PGS), the underlying principle remains the same. The software evaluates the probability of the observed DNA profile under different propositions about the number and identity of contributors, ultimately computing an LR [22] [31].

Q5: Are there disciplines where the LR should not be used? The LR is a general logical framework and can, in principle, be applied to any evidence. The challenge lies in reliably estimating the probabilities P(E|Hp) and P(E|Hd). For disciplines that lack a robust, empirical basis for estimating these probabilities (e.g., some pattern evidence fields), calculating a valid LR may be difficult. In such cases, the focus should be on building the empirical foundations needed to support quantitative evaluation [30].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Core Workflow for LR Calculation and Interpretation

The following diagram illustrates the logical pathway for applying the Likelihood Ratio to forensic evidence, from hypothesis definition to court interpretation.

Protocol: Calculating an LR for a Simple DNA Match

Objective: To compute the Likelihood Ratio for a matching DNA profile found at a crime scene and on a suspect.

Materials & Reagents:

- Reference Sample: From the suspect.

- Evidence Sample: From the crime scene.

- Population Database: A relevant database of DNA profiles to estimate allele frequencies [22].

- Quantitative Software: For statistical computation.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Profiling: Generate DNA profiles from both the reference and evidence samples. Confirm that they match at all tested loci.

- Formulate Hypotheses:

- (Hp): The suspect is the source of the evidence sample.

- (Hd): An unrelated random individual from the population is the source of the evidence sample.

- Calculate Probabilities:

- Compute LR:

- LR = P(E | Hp) / P(E | Hd) = 1 / RMP.

- Example: If the RMP is calculated to be 1 in 1 million, the LR is 1 / (1/1,000,000) = 1,000,000.

- Report and Interpret: Report the LR value and its verbal equivalent (e.g., "The DNA evidence is one million times more likely if the suspect is the source than if an unrelated random person is the source."). This provides strong evidence to support (H_p) [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit

TABLE: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions for LR Studies

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Probabilistic Genotyping Software (PGS) | Essential for calculating LRs from complex DNA evidence, such as mixtures, where multiple contributors are present. It models stochastic effects and deconvolutes the mixture [31]. |

| Validated Population Databases | Provides the allele frequency data necessary to calculate the probability of the evidence under the defense hypothesis (H_d). The choice of database must be relevant to the case [22]. |

| Likelihood Ratio Verbal Scale | A standardized scale used to translate the numerical LR value into a qualitative statement (e.g., "moderate support," "very strong support") for clearer communication in reports and testimony [28]. |

| Fagan Nomogram | A graphical tool (used in medicine and adaptable to forensics) that allows for the visualization of how a prior probability is updated to a posterior probability using the LR. It demonstrates the Bayesian framework intuitively [32] [33]. |

| Uncertainty Analysis Framework | A structured approach (e.g., an "assumptions lattice" and "uncertainty pyramid") for evaluating how different modeling choices and data inputs affect the final LR value, ensuring robust and defensible results [30]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is a Likelihood Ratio (LR) in forensic science? A Likelihood Ratio (LR) is a measure of the strength of forensic evidence. It compares the probability of observing the evidence (E) under two competing hypotheses: the prosecution's hypothesis (Hp) and the defense's hypothesis (Hd). It is calculated as LR = P(E|Hp) / P(E|Hd) [8]. This ratio tells you how much more likely the evidence is under one hypothesis compared to the other.

2. What is the "transposing the conditional" fallacy? The "transposing the conditional" fallacy, also known as the Prosecutor's Fallacy, is a logical error of confusing two different conditional probabilities [7] [29]. It mistakenly equates the probability of the evidence given the hypothesis, P(E|Hp), with the probability of the hypothesis given the evidence, P(Hp|E) [29] [8]. This fallacy can lead to a serious overstatement of the evidence against a defendant.

3. Why should experts avoid stating posterior probabilities? Modern forensic standards recommend that experts avoid stating posterior probabilities (like the probability a defendant is guilty) because doing so requires them to make assumptions about the prior probability of guilt, which is not based on their forensic expertise [8]. This prior probability is the role of the judge or jury. By sticking to the Likelihood Ratio, experts stay within their domain, commenting only on the probability of the evidence under specified hypotheses [8].

4. How do I interpret the value of a Likelihood Ratio? The value of the LR indicates the degree to which the evidence supports one hypothesis over the other. The scale below provides a general guideline for interpretation [8].

| LR Value | Interpretation (Strength of Evidence) |

|---|---|

| > 1 | Supports the prosecution's hypothesis (Hp) |

| 1 | The evidence is neutral; it does not support either hypothesis |

| < 1 | Supports the defense's hypothesis (Hd) |

Troubleshooting Common LR Calculation Issues

Problem: Committing the Prosecutor's Fallacy

- Symptoms: Misinterpreting a small random match probability (RMP) as the probability that the defendant is innocent. For example, stating "The chance that the DNA match is by coincidence is 1 in a million, so the probability the defendant is innocent is 1 in a million."

- Solution: The RMP is P(E|Hd). The probability of innocence is P(Hd|E), which is not the same. Always remember that P(E|Hd) ≠ P(Hd|E). To avoid this, frame your conclusions carefully: "The evidence is [LR value] times more likely if the prosecution's hypothesis is true than if the defense's hypothesis is true" [29] [8].

Problem: Ignoring the Prior Odds

- Symptoms: Presenting a high LR value as definitive proof of guilt without context. The LR updates the prior beliefs (prior odds) to reach the posterior odds.

- Solution: Understand that the LR is just one part of the Bayesian framework. The final judgment depends on the prior odds, which incorporate all non-forensic evidence. The correct formula is: Posterior Odds = Likelihood Ratio × Prior Odds [8].

Problem: Using Incompatible or Non-Mutually Exclusive Hypotheses

- Symptoms: An LR that is difficult to interpret or is misleading because the hypotheses Hp and Hd are poorly defined.

- Solution: Ensure that the prosecution and defense hypotheses are mutually exclusive and clearly defined. The hypotheses must be formulated at the same level of detail (e.g., "source level" vs. "activity level") for the LR to be valid and meaningful [8].

Experimental Protocol: Calculating a Likelihood Ratio

This protocol provides a general framework for calculating a Likelihood Ratio for forensic evidence, such as a DNA profile match.

1. Define the Competing Hypotheses

- Prosecution's Hypothesis (Hp): The defendant is the source of the DNA found at the crime scene.

- Defense's Hypothesis (Hd): Another person, unrelated to the defendant, is the source of the DNA.

2. Calculate P(E|Hp) This is the probability of observing the evidence if the prosecution's hypothesis is true.

- Methodology: If the defendant is truly the source, the expected result is a match. Therefore, for a simple DNA match, this probability is often 1 (or very close to it), assuming no testing errors.

3. Calculate P(E|Hd) This is the probability of observing the evidence if the defense's hypothesis is true. It is the probability that a person randomly selected from the relevant population would also match the DNA profile.

- Methodology: This is typically calculated using the random match probability (RMP). The RMP is estimated using population genetics databases and models to determine how common the observed DNA profile is in the population [8].

4. Compute the Likelihood Ratio Divide the probability from step 2 by the probability from step 3.

- Formula: LR = P(E|Hp) / P(E|Hd)

Example Calculation Summary

| Component | Description | Value in Example |

|---|---|---|

| Evidence (E) | DNA profile from crime scene matches defendant's profile. | Match |

| P(E|Hp) | Probability of a match if defendant is source. | 1 |

| P(E|Hd) | Random Match Probability (RMP). | 1 / 1,000,000 |

| LR | 1 / (1/1,000,000) | 1,000,000 |

Interpretation: The DNA evidence is one million times more likely to be observed if the defendant is the source than if an unrelated random person from the population is the source.

LR Calculation Workflow and Fallacy Pathway

The diagram below illustrates the correct workflow for calculating and using a Likelihood Ratio, and contrasts it with the common pathway that leads to the Prosecutor's Fallacy.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Concepts for LR Calculation

The table below lists key concepts and their functions essential for understanding and calculating Likelihood Ratios.

| Concept | Function & Explanation | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Likelihood Ratio (LR) | The core metric of evidence strength. It quantifies how much more likely the evidence is under one hypothesis compared to an alternative [8]. | ||

| Prosecutor's Fallacy | A common logical error where P(E | Hd) is misinterpreted as P(Hd | E), vastly overstating the evidence against a defendant [7] [29]. |

| Bayes' Theorem | The mathematical framework that correctly relates the LR to prior and posterior odds: Posterior Odds = LR × Prior Odds [8]. | ||

| Random Match Probability (RMP) | A specific form of P(E | Hd). It is the probability that a randomly selected person from a population would match the forensic profile [8]. | |

| Prior Odds | The odds of a hypothesis being true before considering the new forensic evidence. This is typically the domain of the judge or jury [8]. | ||

| Posterior Odds | The odds of a hypothesis being true after incorporating the new forensic evidence via the LR [8]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Likelihood Ratio Implementation

Q1: What is the most common logical pitfall when interpreting a Likelihood Ratio, and how can it be avoided?

The most common logical pitfall is transposing the conditional, also known as the prosecutor's fallacy. This occurs when the probability of the evidence given a proposition (e.g., "the probability of finding this DNA profile if the suspect is not the source") is mistakenly interpreted as the probability of the proposition given the evidence (e.g., "the probability the suspect is not the source given this DNA profile") [34]. To avoid this, the LR should be presented and understood strictly as a measure of the support the evidence provides for one proposition over another, not as a probability statement about the propositions themselves [34].

Q2: Our lab is validating a new LR system. What are the key performance metrics we should assess?

Validation of an LR system should focus on its reliability and validity. Key quantitative metrics to assess are detailed in the table below [35]:

Table: Key Performance Metrics for LR System Validation

| Metric | Description | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Discrimination | The system's ability to distinguish between sources. | A higher value indicates better distinguishing power. |

| Calibration | The agreement between the stated LRs and the observed strength of evidence. | Well-calibrated LRs mean an LR of 1,000 truly corresponds to that level of support. |

| Empirical Validation | Testing the system's performance under casework-like conditions. | Confirms that the theoretical model performs as expected with real data [35]. |

Q3: How do I choose the right pair of propositions for activity-level evaluation?

Activity-level evaluation moves beyond the question of source to address what happened. The choice of propositions must be case-specific and mutually exclusive. They should be crafted based on the framework of circumstances provided in the case information [34]. For example, instead of "Mr. Smith is the source of the DNA," propositions could be "Mr. Smith assaulted the victim" versus "Mr. Smith never had any contact with the victim." This requires considering factors like transfer and persistence of DNA, making a thorough pre-assessment of the case essential [34].

Q4: What are the desiderata for a robust LR-based interpretation framework?

The desired properties for any interpretation framework, as outlined in international guidelines, are [34]:

- Balance: The evaluation should fairly consider the positions of both parties.

- Logic: The reasoning should follow a coherent and mathematically sound framework (i.e., probability theory).

- Transparency: All assumptions, data, and reasoning steps should be clearly stated and open to scrutiny.

- Robustness: The conclusions should be reasonably insensitive to plausible variations in the underlying models or assumptions.

Troubleshooting Common LR Implementation Challenges

Problem: Inconsistent LR results from different statistical models.

- Diagnosis: Model conflict due to different underlying population genetics assumptions or different ways of handling low-template/mixed DNA profiles.

- Solution: Establish strict protocols for which model to use based on the evidence type. Perform empirical validation to understand the performance and limitations of each model in your laboratory's context [35].

Problem: The legal community finds the LR concept difficult to understand.

- Diagnosis: Communication gap between scientific and legal stakeholders.

- Solution: Develop standardized, plain-language explanations and visual aids. Training for scientists on how to present LRs in court is crucial. Leverage resources from standards bodies like NIST, which provide entry points for legal professionals to learn about forensic standards [36].

Problem: The system produces poorly calibrated LRs.

- Diagnosis: The statistical model may not perfectly reflect reality, or the data used to build it may be insufficient.

- Solution: This is a core focus of the paradigm shift towards forensic data science. The solution is to refine models using more relevant and extensive data sets and to implement continuous validation and monitoring of calibration performance [35].

Experimental Protocol for an LR-Based Evaluation

The following workflow details the key stages for conducting a forensically sound, LR-based evaluation of evidence, from initial case review to final reporting.

Title: LR Evaluation Workflow

Procedure:

Case Assessment and Pre-Assessment:

- Purpose: To understand the framework of circumstances and define the relevant questions and propositions for evaluation [34].

- Steps: Review case information with the investigating authority. Identify the alleged activities and the disputed issues. Determine if the questions are investigative (helping to form hypotheses) or evaluative (weighing evidence given competing hypotheses) [34].

Definition of Propositions:

- Purpose: To establish the pair of mutually exclusive propositions (prosecution proposition, Hp, and defense proposition, Hd) that the LR will evaluate. The hierarchy of propositions (source level vs. activity level) is a fundamental concept [34].

- Steps: Formulate propositions at the appropriate level (e.g., source level: "The DNA comes from the suspect" vs. "The DNA comes from an unknown person"; activity level: "The suspect assaulted the victim" vs. "The suspect had no contact with the victim"). For activity level, consider transfer and persistence [34].

Model and Data Selection:

- Purpose: To choose the probabilistic model and relevant population data that will be used to calculate the probabilities of the evidence under each proposition.

- Steps: Select a validated software or algorithm. Choose a relevant reference population database (e.g., geographically appropriate). Document all choices and assumptions for transparency [35].

LR Calculation:

- Purpose: To compute the ratio of the probability of the forensic evidence given the prosecution proposition to the probability given the defense proposition.

- Steps: Input the evidence profile and reference data into the selected model. Perform the computation to obtain the LR value.

Validation and Calibration Check:

- Purpose: To ensure the calculated LR is valid and well-calibrated, meaning its numerical value correctly represents the strength of the evidence [35].

- Steps: Check the system's performance metrics, such as discrimination and calibration, against established validation data. Ensure the result is robust and fit for purpose.

Reporting and Communication:

- Purpose: To convey the findings in a balanced, transparent, and logical way that avoids misleading the court [34].

- Steps: Write a report that clearly states the propositions, the calculated LR, and the limitations of the method. Use verbal qualifiers for the strength of evidence if needed, but always present the numerical LR. Crucially, avoid transposing the conditional in the explanation [34].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table: Key Components for an LR-Based Forensic Framework

| Component | Function | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Probabilistic Genotyping Software (PGT) | Analyzes complex DNA mixtures to compute LRs; the core analytical engine. | STRmix, TrueAllele. Must be empirically validated [35]. |

| Population Databases | Provides allele frequency data to calculate the probability of the evidence under the defense proposition (Hd). | Population-specific databases (e.g., US Caucasian, African American). Critical for a representative LR. |

| Validation Datasets | Used to test and calibrate the entire LR system, ensuring reliability and estimating error rates. | Sets of known-source and mock casework samples [35]. |

| Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) | Ensures consistency, reduces human error, and documents the process for accreditation. | SOPs for case assessment, proposition setting, software use, and reporting [37]. |

| Continuous Professional Training | Maintains and updates examiner skills in logical reasoning, statistics, and courtroom testimony. | Training on the case assessment and interpretation (CAI) framework and avoiding cognitive bias [34] [38]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Resolving the Prosecutor's Fallacy in Testimony

Problem: A common error occurs when the probability of observing evidence given innocence (P(E|I)) is mistakenly presented as the probability of innocence given the evidence (P(I|E)) [8] [2]. This fallacious reasoning can greatly overstate the strength of forensic evidence against a defendant.

Solution:

- Use Likelihood Ratios (LR): Frame conclusions using the formula: LR = P(E|Hp) / P(E|Hd), where Hp is the prosecution's hypothesis and Hd is the defense's hypothesis [8]. This quantifies how much more likely the evidence is under one hypothesis compared to the other, without invading the jury's role by assigning probabilities to the hypotheses themselves [8].

- Explicitly State the Question: Ensure your testimony answers the correct statistical question: "How strong is this evidence?" rather than "Is the defendant guilty?" [7].

- Refer to Established Standards: Follow modern reporting standards recommended by bodies like the European Network of Forensic Science Institutes (ENFSI) and the UK Royal Statistical Society, which advocate for the use of likelihood ratios [8].

Verification: After applying this solution, your testimony should correctly characterize the strength of the evidence without making definitive claims about the defendant's guilt or innocence, thus avoiding the transposed conditional fallacy.

Guide 2: Correcting for Low Prior Probabilities

Problem: Strong forensic evidence (e.g., a high LR from a DNA match) might be misleading if the initial prior probability of guilt is very low, such as when a suspect is identified through a large database search [39].

Solution:

- Incorporate the Base Rate: Actively seek and incorporate relevant base rate information into the analysis. For a database search, the prior probability might be adjusted based on the database size [7].

- Apply Bayes' Theorem Formula: Use the theorem as intended: Posterior Odds = Likelihood Ratio × Prior Odds [3] [8]. Clearly differentiate between the probability of a random match (the random match probability) and the probability that a defendant who matches is innocent (which depends on the prior probability) [7].

Verification: The corrected posterior probability will be significantly lower than the initial, fallacious interpretation when the prior probability is low. This provides a more accurate and scientifically robust assessment of the evidence.

Guide 3: Handling Multiple Pieces of Evidence

Problem: Combining several independent pieces of evidence (e.g., DNA, fingerprint, and blood type) sequentially can be computationally complex and prone to error if not handled systematically [39].

Solution:

- Use Sequential Bayesian Updating: Treat each piece of evidence sequentially. The posterior odds after considering the first piece of evidence become the prior odds for evaluating the next piece of evidence [3] [40].

- Utilize Specialized Software: For complex cases with multiple strands of evidence, employ specialized software tools like SAILR, which is designed to assist forensic scientists in the statistical analysis of likelihood ratios [39].

Verification: The final posterior probability will logically and consistently reflect the cumulative strength of all presented evidence. This process can be visualized and checked at each step to ensure accuracy.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the single most important thing I can do to avoid the prosecutor's fallacy in my reports? The most crucial step is to never equate P(E|H) with P(H|E). Always use the likelihood ratio to report the strength of your findings. This keeps your testimony within the bounds of your forensic expertise and prevents you from making claims about the defendant's guilt, which is the jury's responsibility [8] [7].

FAQ 2: How do I handle non-numeric evidence or evidence where reliable statistics aren't available? The principles of Bayesian reasoning still apply. You can use a qualitative scale (e.g., weak, moderate, strong support) that is logically consistent with the likelihood ratio framework. The key is to express how the evidence updates the prior belief, even if the update cannot be precisely quantified [8].

FAQ 3: A lawyer has asked me, "What is the probability the defendant is guilty based on your evidence?" How should I respond? You should explain that this question cannot be answered by the forensic evidence alone. The correct response is: "My expertise allows me to state how much more likely this evidence is under the prosecution's hypothesis compared to the defense's hypothesis. The probability of guilt depends on this likelihood ratio combined with all the other non-forensic evidence in the case, which is for the court to consider" [8].