The Daubert Standard in Forensic Science: A Complete Guide for Researchers and Drug Development Professionals

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the Daubert standard, the primary framework for admitting expert testimony in federal courts.

The Daubert Standard in Forensic Science: A Complete Guide for Researchers and Drug Development Professionals

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the Daubert standard, the primary framework for admitting expert testimony in federal courts. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the legal foundations, practical application, and strategic optimization of scientific evidence. The guide covers the pivotal 'Daubert Trilogy' of Supreme Court cases, details the key factors for validating methodology, and offers troubleshooting strategies for overcoming admissibility challenges. It also examines Daubert's impact compared to other standards and discusses emerging trends, including recent amendments to Federal Rule 702 and the proposed Rule 707 for AI-generated evidence, equipping scientific experts to navigate the legal landscape effectively.

Understanding Daubert: The Legal Bedrock for Scientific Evidence

The integrity of legal proceedings hinges on the quality of evidence presented, and perhaps no form of evidence is more complex than expert scientific testimony. For forensic science researchers and drug development professionals, the standards governing which expert opinions are admissible in court are not merely legal abstractions; they are the foundational frameworks that determine whether rigorous scientific work will inform justice. For most of the 20th century, the admissibility of scientific evidence in United States courts was governed by the Frye standard, a simple yet rigid test derived from a 1923 Court of Appeals decision regarding the admissibility of polygraph evidence [1] [2].

This standard was ultimately superseded at the federal level by the Daubert standard, a more nuanced and flexible set of criteria established by the Supreme Court's 1993 decision in Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc. [3] [4]. This evolution from Frye to Daubert represents a significant shift in legal thinking, moving the court's role from a passive acceptor of generally accepted science to an active "gatekeeper" of scientific validity and reliability [3] [1]. For scientists, this means their methodologies and principles are subject to direct judicial scrutiny, making an understanding of these standards essential for anyone whose work may intersect with the legal system.

The Frye Era: "General Acceptance" as the Gatekeeper

The Frye standard, originating from Frye v. United States (1923), established a singular, pivotal criterion for admitting scientific evidence: the technique or principle from which the expert's deduction is made must be "sufficiently established to have gained general acceptance in the particular field in which it belongs" [5] [2]. The case itself involved the precursor to the polygraph test, and the court's decision to exclude it was based on its failure to meet this "general acceptance" test [1] [2].

Application and Limitations of Frye

Under Frye, the trial court's role was relatively constrained. The judge did not need to independently evaluate the reliability of the underlying science. Instead, the inquiry was focused on the consensus within the relevant scientific community [5] [6]. If a methodology was generally accepted, the testimony was admissible; if not, it was excluded. This created a bright-line rule that was straightforward to apply.

However, the Frye standard faced mounting criticism over time. Its primary weakness was its conservative nature; it was inherently hostile to novel scientific principles, even if they were demonstrably valid and reliable [7] [4]. "Good science" that had not yet achieved widespread adoption was excluded, while "bad science" that had gained general acceptance was admitted. Furthermore, the standard was criticized as being too vague to reliably manage the increasing complexity of scientific testimony in modern litigation [1] [2].

Table: Key Characteristics of the Frye Standard

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Originating Case | Frye v. United States (1923) [5] |

| Core Test | "General Acceptance" in the relevant scientific community [2] |

| Judicial Role | Limited; defers to the scientific community's consensus [6] |

| Primary Strength | Simple, bright-line rule [6] |

| Primary Weakness | Excludes novel but reliable science; admits generally accepted but potentially unreliable science [1] |

The Daubert Revolution: The Judge as Active Gatekeeper

A fundamental shift occurred in 1993 with the Supreme Court's decision in Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc. The Court held that the Frye standard had been superseded by the Federal Rules of Evidence, particularly Rule 702, which was enacted in 1975 [3] [4]. The Court reasoned that the strict "general acceptance" test of Frye was incompatible with the more liberal and flexible "reliability and relevance" approach embodied in the Federal Rules [5] [1].

The Daubert decision assigned trial judges a specific "gatekeeping role" [3]. It is now the responsibility of the judge to ensure that all expert testimony, whether scientific or not, is not only relevant to the case but also rests on a reliable foundation [3] [4]. To assist judges in this assessment, the Supreme Court provided a non-exhaustive list of factors to consider.

The Five Daubert Factors

The five key factors outlined in the Daubert decision for evaluating the reliability of expert methodology are [3]:

- Testing and Falsifiability: Whether the expert's technique or theory can be (and has been) tested. The court emphasized that a key question is whether the scientific method has been employed—generating hypotheses and conducting experiments to see if they can be falsified [3].

- Peer Review and Publication: Whether the technique or theory has been subjected to peer review and publication. This process helps to ensure that only valid, reliable research is disseminated and provides a measure of quality control [3].

- Known or Potential Error Rate: The known or potential rate of error of the technique used. Understanding a method's error rate is crucial for assessing its accuracy and reliability in practice [3].

- Existence of Standards and Controls: The existence and maintenance of standards and controls concerning the technique's operation. This factor evaluates whether there are protocols that govern the application of the method to minimize subjective interpretation [3].

- General Acceptance: The degree to which the technique or theory is "generally accepted" within the relevant scientific community. While this was the sole factor under Frye, it became just one of several considerations under Daubert [3].

The Court stressed that the focus of the inquiry must be on the expert's methodology and principles, not on the conclusions they generate. The goal is to weed out "junk science" by ensuring that expert opinions are derived from the application of the scientific method [3].

The "Daubert Trilogy": Refining the Standard

The Daubert standard was not formed by a single case but was refined and clarified through two subsequent Supreme Court rulings, collectively known as the "Daubert Trilogy" [3] [4].

General Electric Co. v. Joiner (1997)

This case addressed two critical issues. First, it emphasized that while the focus should be on methodology, "conclusions and methodology are not entirely distinct from one another" [3] [1]. A court is not required to admit an opinion where there is "simply too great an analytical gap between the data and the opinion proffered" [3]. Second, it established that an "abuse of discretion" is the proper standard for appellate courts to use when reviewing a trial court's decision to admit or exclude expert testimony, giving trial judges significant latitude in their gatekeeping function [3] [1].

Kumho Tire Co. v. Carmichael (1999)

The Kumho Tire decision significantly expanded the scope of the Daubert standard. The Court held that the judge's gatekeeping obligation identified in Daubert applies not only to scientific testimony but to all expert testimony based on "technical, or other specialized knowledge" [3] [4]. This meant that the reliability factors outlined in Daubert now applied to engineers, economists, forensic examiners, and other specialists whose testimony is based on skill- or experience-based observation, not just pure science [3] [1].

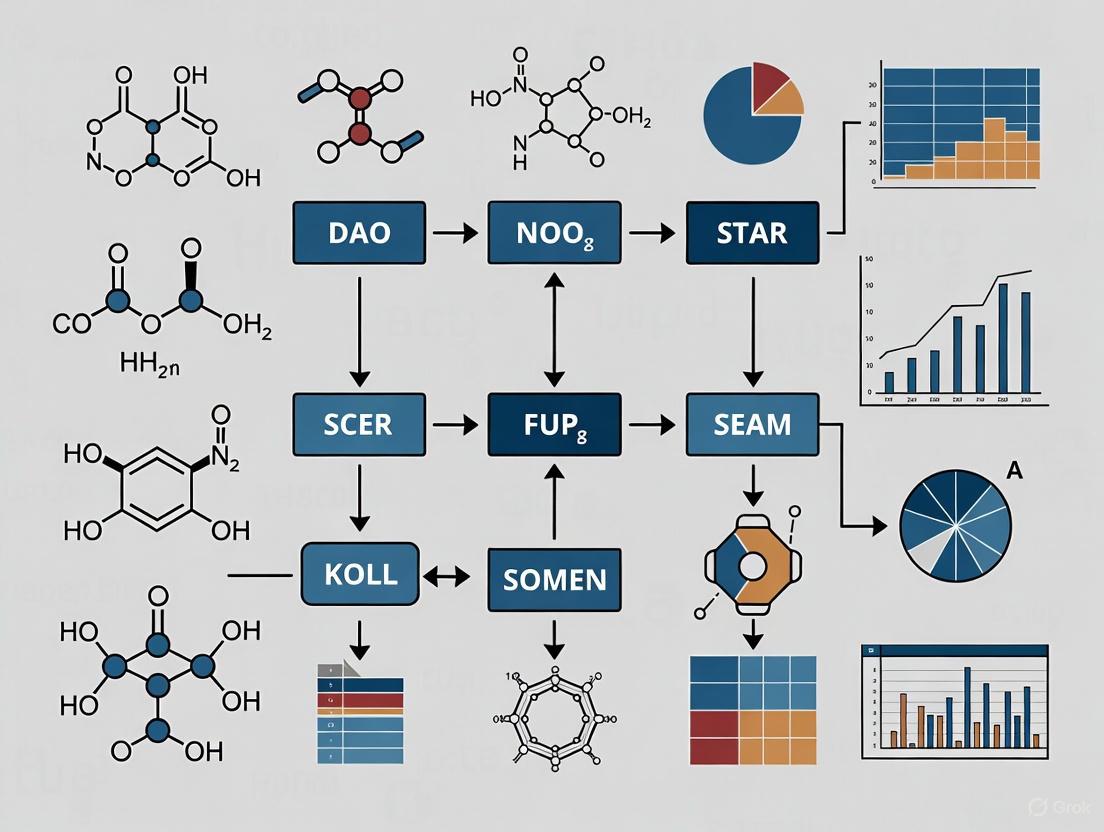

Diagram 1: The evolution of U.S. expert testimony admissibility standards, from the Frye foundation through the Daubert trilogy and subsequent codification in the Federal Rules of Evidence.

Daubert in Practice: A Guide for Forensic Researchers

For the scientific community, the Daubert standard means that the process of preparing for litigation must be as rigorous as the research itself. A Daubert challenge is a pre-trial or trial motion made by opposing counsel to exclude expert testimony on the grounds that it fails to meet the standards of relevance and reliability under Rule 702 [3]. Successfully defending against such a challenge requires meticulous preparation grounded in the Daubert factors.

The Researcher's Protocol for Daubert Compliance

The following methodological protocol is designed to help researchers and scientists structure their work and documentation to withstand judicial scrutiny.

Table: Experimental and Documentation Protocol for Daubert Compliance

| Daubert Factor | Research Objective | Essential Documentation & Methodology |

|---|---|---|

| Testing & Falsifiability | To demonstrate that the methodology is empirically verifiable. | - Detailed experimental protocols.- Laboratory notebooks documenting hypotheses, testing procedures, and raw data.- Clear records of attempts to falsify the hypothesis. |

| Peer Review | To establish that the methodology has been vetted by the scientific community. | - Published articles in reputable, peer-reviewed journals.- Presentations at academic or industry conferences.- Documentation of the peer review process for the specific techniques used. |

| Error Rate | To quantify the accuracy and limitations of the methodology. | - Statistical analysis of experimental results, including confidence intervals.- Data on the method's performance from validation studies.- Acknowledgement of potential sources of error and uncertainty. |

| Standards & Controls | To show that the methodology is applied consistently and objectively. | - Adherence to established industry or scientific standards (e.g., ISO, ASTM).- Documentation of standard operating procedures (SOPs).- Records of calibration, control samples, and quality assurance checks. |

| General Acceptance | To contextualize the methodology within the broader field. | - Literature reviews citing the widespread use of the methodology.- Citations of textbooks or guidelines that endorse the technique.- Survey data or expert affidavits attesting to the method's acceptance. |

The Scientist's Litigation Toolkit

When preparing to serve as an expert or to have one's research presented in court, the following "reagents"—the essential materials and preparations—are critical for constructing a defensible position.

Table: Essential Materials for Expert Testimony Preparation

| Toolkit Item | Function in the Litigation Process |

|---|---|

| Comprehensive Report | Serves as the primary document for judicial review; must detail the expert's opinions, the basis for them, and the reliable principles and methods applied to the facts [8]. |

| Curriculum Vitae (CV) | Establishes the expert's qualifications as being based on "knowledge, skill, experience, training, or education" as required by Rule 702 [8]. |

| Complete Data Archive | Provides the "sufficient facts or data" underlying the opinion; must be available for audit and cross-examination to demonstrate the opinion is not speculative [3] [9]. |

| Peer-Reviewed Literature | Acts as objective, third-party validation of the reliability and general acceptance of the methods employed [3]. |

| Visual Aids & Analogies | Helps the judge and jury understand complex technical concepts, fulfilling the requirement that the testimony "help the trier of fact" [8]. |

Diagram 2: The iterative cycle of scientific work and legal admissibility, showing how robust research and thorough documentation underpin defensible expert testimony.

Current Landscape: FRE 702 Amendment and State Variations

The legal standards for expert testimony continue to evolve. In December 2023, an amendment to Federal Rule of Evidence 702 took effect, further clarifying and strengthening the judge's gatekeeping role [9]. The amendment emphasizes that the proponent of the expert testimony must establish its admissibility by a preponderance of the evidence and that the court must ensure each expert opinion stays within the bounds of what can be concluded from a reliable application of the expert's basis and methodology [9]. This amendment counteracts a trend where some courts deemed challenges to an expert's application of a method as going only to the "weight" of the evidence, not its "admissibility" [9].

While federal courts uniformly apply Daubert, state courts are a patchwork. The majority of states have adopted some form of the Daubert standard, but several significant jurisdictions, including California, Illinois, and Pennsylvania, continue to adhere to the Frye standard [1] [4]. Other states have adopted hybrid or modified versions of the standards. For any scientist or researcher, it is imperative to understand the specific jurisdiction's applicable rule, as the preparation and admissibility of expert testimony can differ dramatically [6].

The evolution from Frye to Daubert represents the legal system's ongoing effort to grapple with the complexities of modern science. For the forensic science and drug development communities, this shift places a premium on methodological rigor, transparency, and empirical validation. The Daubert standard, with its focus on the reliability of principles and methods, effectively mandates that science presented in the courtroom must meet the same standards as science conducted in the laboratory. By understanding the history and requirements of these evidence standards, researchers can not only better defend their work in legal proceedings but also contribute to the administration of a more just and scientifically sound legal system.

The Daubert Trilogy represents a series of three pivotal U.S. Supreme Court rulings that fundamentally reshaped the standards for admitting expert testimony in federal courts and many state jurisdictions. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding this legal framework is crucial, as it establishes the criteria by which scientific evidence is evaluated in legal proceedings. These decisions transitioned the legal standard from the general acceptance test of Frye v. United States (1923) to a more nuanced approach that emphasizes scientific validity and methodological reliability [4] [3]. This evolution places the trial judge in the role of "gatekeeper" for scientific evidence, requiring them to ensure that proffered expert testimony is not only relevant but also rests on a reliable foundation [10] [4].

The Trilogy's impact is particularly significant in product liability litigation, toxic torts, and forensic science, where complex scientific evidence often determines case outcomes. Recent developments, including 2023 amendments to Federal Rule of Evidence 702, have further clarified and emphasized that the proponent of expert testimony must demonstrate its admissibility by a preponderance of the evidence, reinforcing the judiciary's gatekeeping function [11]. This whitepaper examines the three cornerstone cases of the Daubert Trilogy, their integration into the Federal Rules of Evidence, and their practical implications for scientific research and testimony.

The Pre-Daubert Landscape: Frye's "General Acceptance" Standard

Prior to the Daubert Trilogy, the dominant standard for admitting scientific evidence in United States courts came from the 1923 case Frye v. United States [4] [3]. The Frye standard focused on whether the scientific principle or technique in question had gained "general acceptance" in its relevant field [12] [10]. While this standard provided a straightforward test for courts, critics argued that it could exclude novel, yet valid, scientific evidence simply because it had not yet achieved widespread recognition [4]. The Frye standard maintained its authority for decades, even after the adoption of the Federal Rules of Evidence in 1975, which contained no explicit "general acceptance" requirement [4].

The Daubert Trilogy: A Three-Act Transformation

The Daubert Trilogy consists of three Supreme Court decisions that progressively developed a new framework for assessing expert testimony. The table below summarizes the key focus and holding of each case.

Table 1: The Three Cases of the Daubert Trilogy

| Case Name & Citation | Year | Key Focus | Core Legal Holding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc. [10] | 1993 | Admissibility of Scientific Evidence | The Frye standard was superseded by the Federal Rules of Evidence. Trial judges must act as gatekeepers to ensure expert testimony is both relevant and reliable. |

| General Electric Co. v. Joiner [3] | 1997 | Appellate Review & Analytical Gaps | Appellate courts must review a trial judge's decision to admit or exclude expert testimony under an abuse-of-discretion standard. An expert's conclusion must be connected to the underlying data. |

| Kumho Tire Co. v. Carmichael [3] | 1999 | Application to Non-Scientific Experts | The Daubert gatekeeping function applies to all expert testimony, based on "scientific, technical, or other specialized knowledge," not just to scientific testimony. |

Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (1993)

In Daubert, the Supreme Court addressed the admissibility of expert testimony alleging that the anti-nausea drug Bendectin caused birth defects [3]. The Court held that the Federal Rules of Evidence, particularly Rule 702, had displaced the Frye standard [10] [4]. The ruling tasked trial judges with a gatekeeping responsibility to "ensure that any and all scientific testimony or evidence admitted is not only relevant, but reliable" [10]. To guide this assessment, the Court provided a non-exhaustive, flexible list of factors:

- Whether the theory or technique can be (and has been) tested: The scientific validity must be grounded in the scientific method, implying that it is falsifiable, refutable, and testable [10] [4] [3].

- Whether it has been subjected to peer review and publication: Peer review is a component of "good science" that helps identify methodological flaws [10] [3].

- The known or potential error rate: The court should consider the rate of error associated with a particular scientific technique [10] [13] [3].

- The existence and maintenance of standards controlling the technique's operation: The presence of standards and controls indicates a more reliable methodology [10] [3].

- General acceptance in the relevant scientific community: While Frye's "general acceptance" was no longer the sole test, it remained a relevant factor for consideration [10] [4] [3].

General Electric Co. v. Joiner (1997)

The Joiner case reinforced and refined the Daubert decision in two critical ways. First, it established that appellate courts must review a trial judge's decision to admit or exclude expert evidence under an abuse-of-discretion standard, making it harder to overturn these rulings on appeal [12] [3]. Second, the Court acknowledged that while the focus of the inquiry should be on the expert's methodology, "conclusions and methodology are not entirely distinct from one another" [3]. It held that a court may exclude an expert's opinion if there is "too great an analytical gap between the data and the opinion proffered" [12] [3]. This prevents experts from offering unsupported conclusions, or ipse dixit, that are not logically derived from the applied methodology [3].

Kumho Tire Co. v. Carmichael (1999)

Kumho Tire expanded the reach of the Daubert standard beyond "scientific" knowledge. The Supreme Court held that a trial judge's gatekeeping obligation applies to all expert testimony based on "technical, or other specialized knowledge," as outlined in Federal Rule of Evidence 702 [3]. This meant that the Daubert framework now governed the admissibility of testimony from engineers, accountants, forensic examiners, and other non-scientific experts [10] [3]. The Court also clarified that the Daubert factors are flexible and may not all be applicable in every case; the trial judge has discretion to determine how to assess reliability based on the particular nature of the testimony [3].

Integration into Federal Rule of Evidence 702

The principles of the Daubert Trilogy were subsequently codified into the text of Federal Rule of Evidence 702, which was amended in 2000 and again in 2023 to clarify the standard [11]. The rule now states that a qualified expert may testify if:

- The expert’s knowledge will help the trier of fact understand the evidence;

- The testimony is based on sufficient facts or data;

- The testimony is the product of reliable principles and methods; and

- The expert has reliably applied the principles and methods to the facts of the case [11] [3].

The 2023 amendments specifically emphasized that the proponent of the testimony must establish its admissibility by a preponderance of the evidence and that challenges to the sufficiency of an expert's basis or the application of their methodology are questions of admissibility, not merely weight [11].

The following diagram illustrates the logical progression and key holdings of the Daubert Trilogy and its relationship with the Federal Rules of Evidence.

The Daubert Standard in Practice: Methodologies & Protocols

For scientific evidence to satisfy the Daubert standard, the underlying research and methodologies must be rigorously designed and implemented. The following experimental protocols and reagent solutions are representative of the approaches required to build a reliable foundation for expert testimony.

Experimental Protocol for Forensic Validation Studies

A key implication of Daubert and the 2009 NAS Report on forensic science is the need for robust validation studies to establish the scientific validity and error rates of forensic disciplines [13]. The protocol below, inspired by pioneering work at the Houston Forensic Science Center (HFSC), outlines a methodology for conducting blind proficiency testing [13].

Objective: To empirically determine the foundational validity of a forensic method and its error rate as practiced in a specific laboratory, thereby providing the statistical data required by Daubert [13].

Materials & Reagents:

- Mock evidence samples (e.g., synthetic fingerprints, prepared tool marks, controlled substance analogues)

- Authentic case evidence (for known positive/negative controls)

- Standard laboratory equipment and reagents specific to the discipline (e.g., fuming cyanoacrylate for latent prints, comparison microscopes for firearms)

- Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation & Introduction: The quality division or a designated case manager prepares mock evidence samples that are forensically realistic. These samples are then introduced into the laboratory's ordinary workflow, ensuring analysts are blind to the fact that they are being tested [13].

- Blinded Analysis: Analysts process, analyze, and interpret the mock evidence samples using the same standard operating procedures (SOPs) applied to actual casework. This tests the entire process chain, from evidence handling to result reporting [13].

- Data Collection & Analysis: Results from the blind tests are systematically collected. The data is analyzed to calculate false positive rates, false negative rates, and overall proficiency. The difficulty level of each sample can also be factored into the analysis [13].

- Iterative Refinement: The results are used to identify potential sources of error, refine methodologies, and implement corrective actions. The testing program is ongoing to continuously monitor performance and establish statistical confidence in the error rates [13].

Research Reagent Solutions for Daubert-Compliant Science

The following table details key materials and their functions in building a scientifically reliable foundation for expert testimony, particularly in fields like toxicology and drug development.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Forensics and Drug Development

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|

| Cell-Based Assay Systems | Used in toxicology to screen for compound toxicity and understand mechanisms of action at the cellular level. Provides a foundation for causal opinions. |

| Animal Models | Employed in pre-clinical drug development and toxicology studies to assess the physiological effects of a substance in a complex biological system. |

| Positive & Negative Controls | Essential for validating any forensic or analytical test. They ensure the testing methodology is functioning correctly and help rule out contamination or false results. |

| Certified Reference Materials | Provides a known standard with a certified composition or property. Critical for calibrating instruments and verifying the accuracy of quantitative analyses. |

| Blinded Proficiency Samples | Mock evidence introduced into the workflow to objectively measure an analyst's or a laboratory's performance and determine empirical error rates [13]. |

Implications for Forensic Science & Legal Proceedings

The Daubert framework has profound implications for how scientific evidence is presented and challenged in legal proceedings.

The Daubert Challenge

A Daubert challenge is a motion, often filed pre-trial, by opposing counsel to exclude the testimony of an expert witness [10] [3]. The challenge argues that the expert's testimony fails to meet the reliability and relevance standards of Rule 702 and the Daubert factors [3] [14]. To defend against such a challenge, experts and the attorneys who proffer them must be prepared to demonstrate:

- The testability and falsifiability of the underlying theory [3] [14].

- That the methodology has been subjected to peer review and publication [3] [14].

- The known or potential error rate of the technique, if applicable [13] [3] [14].

- The existence of standards and controls governing the method's application [3] [14].

- The general acceptance of the methodology in the relevant scientific community [3] [14].

Specific Application to Forensic Science Research

The forensic sciences have faced significant scrutiny under Daubert, particularly following the 2009 National Academy of Sciences (NAS) report, which found that many forensic disciplines, apart from DNA, lacked a solid scientific foundation and established error rates [13] [15]. The diagram below outlines the decision pathway a judge must navigate when assessing forensic evidence under Daubert.

For forensic science researchers, this legal landscape creates a pressing need to:

- Conduct Rigorous Validation Studies: Research must move beyond precedent and focus on empirically testing the core assumptions of forensic disciplines [13] [15].

- Establish Empirical Error Rates: As emphasized in Daubert and the NAS report, a known or potential error rate is essential for assessing the reliability and probative value of forensic evidence [13]. Blind proficiency testing is a key methodology for generating this data [13].

- Address Sources of Bias: Research should investigate and develop standards to minimize contextual and confirmation biases in forensic examinations [13].

- Publish in Peer-Reviewed Literature: To demonstrate reliability and gain acceptance, forensic science research must undergo the scrutiny of the broader scientific community through peer-reviewed publication [15].

The Daubert Trilogy established a transformative legal framework that demands a more rigorous and scientifically grounded approach to expert testimony. By making judges the gatekeepers of scientific evidence and providing flexible factors for assessing reliability, the Trilogy has pushed the legal and scientific communities closer together. For forensic science researchers and drug development professionals, understanding Daubert, Joiner, and Kumho Tire is not merely an academic exercise. It is a practical necessity for designing research that will withstand legal scrutiny, for providing effective testimony, and ultimately, for ensuring that the evidence presented in court is founded on reliable scientific principles. The ongoing evolution of this standard, including the 2023 amendments to Rule 702, underscores the critical and enduring interaction between law and science.

The concept of the judge as a "gatekeeper" for scientific evidence represents a fundamental shift in American jurisprudence, establishing courts as critical filters for ensuring only reliable and relevant expert testimony reaches the trier of fact. This gatekeeping role formally crystallized in the 1993 landmark case Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc., where the United States Supreme Court articulated that trial judges must perform a "preliminary assessment of whether the reasoning or methodology underlying the testimony is scientifically valid and of whether that reasoning or methodology properly can be applied to the facts in issue" [10]. This decision effectively displaced the previous Frye standard of "general acceptance" in the scientific community, which had governed expert testimony admissibility for decades [1].

For forensic science researchers and drug development professionals, understanding this judicial gatekeeping function is not merely academic—it directly impacts how scientific evidence is evaluated in litigation and whether research methodologies will withstand judicial scrutiny. The gatekeeping role requires judges to ensure that expert testimony "both rests on a reliable foundation and is relevant to the task at hand" [10], creating a critical interface between law and science that demands rigorous methodology from researchers and sophisticated scientific understanding from judges.

The Daubert Standard and Its Evolution

The Daubert Trilogy: Foundation of Modern Gatekeeping

The current framework for evaluating expert testimony rests on three pivotal Supreme Court cases collectively known as the "Daubert Trilogy":

- Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (1993): Established the judge's gatekeeping role and provided non-exhaustive factors for evaluating scientific validity [10] [3]

- General Electric Co. v. Joiner (1997): Clarified that appellate courts should review a trial court's admissibility decision for "abuse of discretion" and emphasized that there must be a connection between the expert's opinion and the data [3] [1]

- Kumho Tire Co. v. Carmichael (1999): Extended the Daubert standard to all expert testimony, including "technical, or other specialized knowledge" [3] [1]

This trilogy collectively transformed the judge's role from a passive observer to an active evaluator of the methodological soundness of proffered expert evidence.

The Daubert Factors: Evaluating Scientific Validity

Under Daubert, trial courts consider several factors to determine whether expert methodology is scientifically valid:

Table: Daubert Factors for Evaluating Scientific Evidence

| Factor | Judicial Inquiry | Relevance for Researchers |

|---|---|---|

| Testing | Whether the technique or theory can be and has been tested | Research protocols should emphasize falsifiability and empirical testing |

| Peer Review | Whether the method has been subjected to publication and peer review | Pursuing publication in reputable journals becomes essential for legal admissibility |

| Error Rate | The known or potential error rate of the technique | Method validation studies should include error rate analysis |

| Standards | The existence and maintenance of standards controlling operation | Adherence to established laboratory protocols and SOPs is crucial |

| General Acceptance | Whether the method has gained widespread acceptance in the relevant scientific community | Consensus building through professional organizations and publications matters |

These factors are not a "definitive checklist or test" [10] but rather flexible guidelines that judges may adapt to the specific circumstances of each case.

The 2023 Amendment to Federal Rule of Evidence 702

A significant development in the judge's gatekeeping role occurred in December 2023, when an amendment to Federal Rule of Evidence 702 took effect. This amendment clarified and emphasized three key aspects [16] [17]:

- The proponent's burden: The party offering expert testimony must demonstrate its admissibility by a preponderance of the evidence

- Court's gatekeeping responsibility: Judges have an ongoing duty to ensure expert testimony meets Rule 702 standards

- Reliability requirement: Expert opinions must reflect a reliable application of principles and methods to the facts

The amendment responded to concerns that courts had been too liberal in admitting expert testimony, with the Advisory Committee noting that the change was "designed to emphasize that judicial gatekeeping is essential" [17]. For researchers, this underscores the importance of maintaining rigorous standards throughout the research process.

The Gatekeeping Process in Practice

Procedural Mechanisms for Screening Evidence

The judicial gatekeeping function operates primarily through specific procedural mechanisms:

- Daubert Motions: Formal requests to exclude expert testimony based on unreliability [3]

- Motions in Limine: Pretrial requests for judicial determination on evidence admissibility [10]

- Daubert Hearings: Evidentiary hearings where judges evaluate the methodological soundness of expert testimony [10]

These procedural tools allow parties to challenge opposing experts before trial and enable judges to fulfill their gatekeeping function systematically.

The Gatekeeping Workflow: From Challenge to Ruling

The following diagram illustrates the judicial gatekeeping process for expert testimony:

Gatekeeping in Forensic Science: Addressing the "Daubert Dilemma"

In forensic science, courts face what scholars have termed "Daubert's dilemma"—the tension between requiring rigorous proof of scientific validity and the practical realities of criminal prosecution [13]. Despite Daubert's call for empirical validation, many forensic disciplines traditionally lacked robust error rate statistics. As noted in the landmark 2009 National Academy of Sciences report, "no forensic method other than nuclear DNA analysis has been rigorously shown to have the capacity to consistently and with a high degree of certainty support conclusions about 'individualization'" [13].

This dilemma has created significant challenges for judicial gatekeeping in criminal cases, where courts have often admitted forensic evidence without requiring proof of foundational validity. For forensic researchers, this underscores the critical need to:

- Develop empirical measures of error rates

- Implement blind proficiency testing

- Conduct method validation studies

- Establish statistical foundations for forensic disciplines

Methodological Protocols for Court-Ready Science

Validation Studies: Establishing Foundational Reliability

For scientific evidence to withstand Daubert scrutiny, researchers must conduct appropriate validation studies. These studies should demonstrate:

- Foundational Validity: The scientific principle is valid for its intended purpose

- Applied Validity: The principle has been properly applied in the specific case

- Methodological Rigor: The research follows established scientific protocols

Table: Essential Components of Method Validation for Daubert Purposes

| Validation Component | Protocol Requirements | Judicial Evaluation Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Experimental Design | Controls, blinding, randomization, sample size justification | Whether the design can support causal inferences |

| Error Rate Calculation | Statistical analysis of false positive/negative rates, confidence intervals | Quantifiable measure of reliability |

| Peer Review | Submission to reputable journals, addressing reviewer comments | Independent scrutiny by scientific community |

| Standardization | Established protocols, certification requirements, quality control | Consistency and reproducibility of methods |

| General Acceptance | Adoption in clinical guidelines, regulatory approvals, professional standards | Consensus within relevant scientific field |

Blind Proficiency Testing: A Model for Forensic Science

In response to Daubert's requirement for known error rates, progressive forensic laboratories have implemented blind testing protocols. The Houston Forensic Science Center (HFSC), for example, has established blind proficiency testing in six disciplines, providing a model for generating the empirical data Daubert demands [13].

Experimental Protocol: Blind Proficiency Testing

- Sample Introduction: Mock evidence samples are introduced into the ordinary workflow without analysts' knowledge

- Normal Processing: Samples undergo standard laboratory procedures and analysis

- Result Evaluation: Independent assessment of accuracy compared to known standards

- Error Rate Calculation: Statistical analysis of performance across multiple trials

- Process Improvement: Refinement of methodologies based on identified weaknesses

This approach generates the empirical data needed to establish error rates and provides quality control insights across the entire evidence processing system [13].

For research intended to support expert testimony, several methodological resources are essential:

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Court-Ready Science

| Resource Category | Specific Applications | Function in Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Analysis Packages | R, SAS, SPSS, Python SciPy | Error rate calculation, confidence intervals, significance testing |

| Reference Standards | NIST reference materials, certified controls | Method calibration and accuracy verification |

| Blinding Protocols | Case managers, sample randomization | Minimizing cognitive bias in analysis |

| Data Integrity Tools | Electronic lab notebooks, blockchain timestamping | Ensuring research reproducibility and audit trails |

| Quality Control Systems | Proficiency testing, equipment calibration | Maintaining methodological standards and controls |

Strategic Implications for Researchers and Professionals

Designing Daubert-Resistant Research Protocols

For forensic researchers and drug development professionals, anticipating judicial gatekeeping requires strategic research design:

- Document Methodological Choices: Maintain clear records of protocol decisions and their scientific rationale

- Quantify Uncertainty: Calculate error rates, confidence intervals, and limitations explicitly

- Seek External Validation: Pursue peer-reviewed publication and independent verification

- Address Alternative Explanations: Systematically consider and rule out competing hypotheses

- Maintain Methodological Consistency: Apply uniform standards across studies and analyses

Navigating the Gatekeeping Landscape Post-2023 Amendment

The 2023 amendment to FRE 702 has practical implications for researchers involved in litigation:

- Enhanced Documentation: The clarified burden means proponents must comprehensively document methodological reliability

- Application Rigor: Courts now more closely examine whether methods were reliably applied to case facts

- Ongoing Assessment: The gatekeeping duty continues throughout the expert's testimony, not just pretrial

- Increased Judicial Engagement: Judges are taking a more active role in evaluating scientific reliability [16]

The judicial gatekeeping role established in Daubert and refined through subsequent rulings represents a critical interface between scientific inquiry and legal process. For researchers, understanding this function is not merely about defending methodologies in court—it is about embracing a standard of rigor that serves both scientific truth and legal justice. As courts continue to refine their approach to screening expert evidence, particularly through updated procedural rules like the 2023 amendment to FRE 702, the research community must correspondingly elevate its commitment to transparent, validated, and methodologically sound science.

The judge as gatekeeper serves not as a barrier to scientific evidence but as a quality control mechanism that ultimately strengthens the integrity of both science and law. For forensic science researchers and drug development professionals, this landscape demands nothing less than exemplary scientific practice—precisely the standard that advances both knowledge and justice.

In forensic science research and development, the line between scientifically valid evidence and "junk science" carries profound implications for judicial outcomes, public safety, and scientific integrity. The Daubert standard, established in the 1993 U.S. Supreme Court case Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc., provides a systematic framework for this discrimination, elevating the trial judge to a "gatekeeper" responsible for ensuring that expert testimony rests on a reliable foundation and is relevant to the case [4] [10]. This standard superseded the earlier Frye standard, which had focused exclusively on whether a scientific technique had "gained general acceptance in the particular field in which it belongs" [4]. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding Daubert's principles is essential not only for preparing for courtroom testimony but for structuring rigorous, defensible research protocols that withstand critical scrutiny across scientific and legal domains.

The Daubert trilogy—Daubert (1993), General Electric Co. v. Joiner (1997), and Kumho Tire Co. v. Carmichael (1999)—collectively established that the judge's gatekeeping function applies to all expert testimony, including non-scientific technical and other specialized knowledge [4] [3]. This evolution in legal standards has fundamentally shifted how scientific evidence is evaluated in federal courts and most state jurisdictions, with profound implications for the presentation of forensic and research findings in legal proceedings.

The Core Principles of the Daubert Standard

The Five Daubert Factors

The Daubert standard provides a non-exhaustive list of factors to assess the reliability of scientific testimony. These factors are not a rigid checklist but rather flexible guidelines for evaluating scientific validity [4] [10] [3].

Whether the theory or technique can be and has been tested: The foremost question is whether the expert's conclusion is based on sufficient facts or data, and whether the conclusion is the product of reliable principles and methods reliably applied to the facts of the case. The focus is on methodology rather than solely on conclusions. Scientific knowledge must be derived from the scientific method, involving the formulation of hypotheses and conducting experiments to prove or falsify them [4] [3].

Whether the theory or technique has been subjected to peer review and publication: Peer review represents the evaluation of scientific work by other experts in the same field, serving as a quality control mechanism to ensure only valid, reliable research is published. Publication in peer-reviewed journals suggests that the methodology has withstood preliminary scrutiny by the scientific community [4] [10].

The known or potential error rate of the technique: To determine methodological accuracy, the court must examine procedures for flaws that may produce errors. The ability to provide a numerical error rate enables the court to analyze the likelihood of inaccuracy. Techniques with known, acceptable error rates are more likely to be deemed reliable [4] [3].

The existence and maintenance of standards controlling the technique's operation: The presence of established protocols, calibration standards, and operational controls significantly enhances the reliability assessment. Consistent application of standardized procedures demonstrates methodological rigor [10] [3].

Whether the theory or technique has attained widespread acceptance in a relevant scientific community: While no longer the sole determinant as under Frye, general acceptance remains a relevant factor. Widespread use and acceptance by peers in the relevant field provides persuasive evidence of reliability, though novel methods may still be admissible if otherwise scientifically sound [4] [10].

The Legal Foundation and Evolution

The Daubert standard finds its authority in Rule 702 of the Federal Rules of Evidence, which states that an expert witness qualified by "knowledge, skill, experience, training, or education" may testify if [4] [10] [3]:

- The expert's scientific, technical, or other specialized knowledge will help the trier of fact to understand the evidence or to determine a fact in issue;

- The testimony is based on sufficient facts or data;

- The testimony is the product of reliable principles and methods; and

- The expert has reliably applied the principles and methods to the facts of the case.

The subsequent cases in the Daubert trilogy refined this standard. General Electric Co. v. Joiner (1997) established that appellate courts should review a trial court's decision to admit or exclude expert testimony under an "abuse of discretion" standard, and emphasized that conclusions must be connected to underlying data by more than the "ipse dixit" (unsupported assertion) of the expert [4] [3]. Kumho Tire Co. v. Carmichael (1999) extended the Daubert standard to include all expert testimony, not just scientific testimony, applying the same principles to "technical, or other specialized knowledge" [4] [10] [3].

Figure 1: Evolution of the Daubert Standard from Frye to Modern Application

Quantitative Assessment Frameworks for Scientific Evidence

Empirical Metrics for Reliability Assessment

The Daubert factors necessitate quantitative and qualitative metrics for evaluating scientific evidence. The following table summarizes key assessment parameters across different forensic and research domains:

Table 1: Quantitative Assessment Frameworks for Scientific Evidence Under Daubert

| Daubert Factor | Assessment Metric | Forensic Example | Drug Development Example | Target Threshold |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Testing & Reliability | Test-retest reliability | Fingerprint analysis consistency [18] | Pharmacokinetic assay reproducibility | ICC > 0.9 [19] |

| Peer Review | Publication count & journal impact | Publications on ballistic analysis methods | Clinical trial results in peer-reviewed journals | Acceptance in relevant scientific community [4] |

| Error Rates | Known/potential error rate | False positive in DNA mixture interpretation [4] | False discovery rate in high-throughput screening | Established error rate with confidence intervals [3] |

| Standards & Controls | Protocol standardization | ANSI/NIST standards for fingerprint data [3] | GLP/GMP compliance in assay validation | Documented standard operating procedures [3] |

| General Acceptance | Adoption in relevant field | Use in forensic laboratories worldwide | Adoption in clinical practice guidelines | Widespread use in relevant scientific community [4] |

Case Study: The Personality Assessment Inventory (PAI)

The application of psychological tests in legal proceedings provides an instructive case study in Daubert compliance. The Personality Assessment Inventory (PAI), a psychological assessment instrument, demonstrates how scientific evidence can be structured to meet Daubert standards [19]:

- Testing and Assessment: The PAI was developed following construct validation approaches with empirical evaluation of items, prioritizing content breadth and discriminant validity. The community normative sample included 1,000 cases using random-stratified sampling to match U.S. census demographics [19].

- Error Rate Quantification: The PAI incorporates multiple validity scales with demonstrated diagnostic efficiency. For instance, research on the Negative Impression Management (NIM) scale and Malingering Index (MAL) provides empirical data on their accuracy in detecting response distortion [19].

- Standardization: The PAI manual provides comprehensive guidelines for administration, scoring, and interpretation, ensuring consistent application across settings [19].

- Peer Review and Acceptance: With hundreds of research studies published in peer-reviewed journals and widespread use in forensic contexts, the PAI has attained substantial acceptance within psychological practice [19].

This empirical foundation positions the PAI to generally meet Daubert standards for admissibility in court proceedings involving psychological assessment [19].

Experimental Design & Methodological Protocols

Validation Frameworks for Forensic Methods

Robust experimental design is fundamental to establishing Daubert-compliant scientific evidence. The following protocols provide methodological frameworks for validating forensic and research techniques:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents & Methodological Solutions for Daubert-Compliant Research

| Research Component | Function | Daubert Factor Addressed | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blinded Procedures | Eliminates confirmation bias during data collection and interpretation | Testing/Reliability | Blinded sample analysis in forensic toxicology |

| Control Samples | Establishes baseline measurements and detects contamination | Standards/Controls | Negative/positive controls in DNA analysis |

| Standard Reference Materials | Calibrates instruments and validates methods | Standards/Controls | NIST standard references for controlled substances |

| Proficiency Testing | Assesses analyst competency and method performance | Error Rate | External proficiency tests in forensic laboratories |

| Statistical Analysis Plan | Pre-specifies analytical approach to minimize data dredging | Testing/Reliability | Pre-defined primary endpoints in clinical trials |

| Independent Replication | Confirms findings through separate investigators | Peer Review | Multi-laboratory validation studies |

Protocol for Technical Validation: 3D Laser Scanning

The adoption of 3D laser scanning technology in crime scene investigation illustrates a comprehensive Daubert validation approach. In recent challenges, courts have admitted 3D scanning evidence after evaluating the following technical parameters [18]:

- Accuracy Testing: Multiple measurements of known distances establish methodological precision. For example, FARO scanners demonstrated a known error rate of 1 millimeter at 10 meters [18].

- Repeatability Studies: The same scene captured by different operators using the same equipment produces consistent results, establishing reliability [18].

- Peer Review: Publication of validation studies in journals such as the Association for Crime Scene Reconstruction provides independent scientific scrutiny [18].

- Standardization: Established protocols for scanner calibration, data capture, and processing ensure consistent application [18].

- General Acceptance: Widespread adoption by law enforcement agencies and forensic investigators demonstrates community acceptance [18].

This multi-faceted validation approach successfully withstood Daubert challenges in multiple jurisdictions, establishing 3D laser scanning as admissible scientific evidence [18].

Figure 2: Daubert-Compliant Research Workflow from Hypothesis to Courtroom

Implementation in Legal and Research Contexts

The Daubert Challenge Process

A Daubert challenge represents a legal motion to exclude expert testimony based on failure to meet the standards of reliability and relevance [3]. These challenges typically occur before trial through motions in limine, though they may also be raised during trial [4]. Successful challenges often identify one or more of these deficiencies:

- Analytical Gaps: A disconnect between the data and the expert's conclusions, termed the "ipse dixit" of the expert [3].

- Unsubstantiated Error Rates: Inability to provide a known or potential rate of error for the methodology [3].

- Lack of Standardization: Absence of established protocols and controls governing the technique's application [3].

- Insufficient Peer Review: Limited or non-existent publication in peer-reviewed literature [3].

- Non-Testable Propositions: Theories or techniques that cannot be or have not been empirically tested [3].

Strategic timing is crucial in Daubert challenges, with motions typically filed after the close of discovery but well in advance of trial to allow adequate evaluation [4].

Jurisdictional Variations in Application

While the Daubert standard governs federal courts, state jurisdictions vary in their adherence to different evidence standards:

Table 3: Jurisdictional Application of Expert Testimony Standards

| Standard | Jurisdictions | Key Differentiating Factor |

|---|---|---|

| Daubert | Federal Courts, AL, AZ, GA, MA, NY (in part) | Judge as gatekeeper applying flexible reliability factors [6] |

| Frye | CA, IL, PA, WA, NY (in part) | Focus on "general acceptance" in relevant scientific community [4] [6] |

| Modified Daubert | CO, IN, IA, TX, VA | Daubert principles adapted with state-specific modifications [6] |

| Hybrid Approaches | NJ, FL, NM | Varying applications depending on case type or specific rules [6] |

This jurisdictional variation necessitates that researchers and forensic experts understand the specific evidence standards applicable in their legal context. The ongoing evolution of these standards underscores the importance of maintaining rigorous, scientifically defensible methodologies regardless of jurisdiction.

The Daubert standard represents a crucial interface between scientific inquiry and legal decision-making, establishing a systematic framework for discriminating between scientifically valid knowledge and "junk science." For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the principles enshrined in Daubert align closely with fundamental scientific values: hypothesis testing, methodological transparency, error quantification, peer review, and standardized protocols. By incorporating these principles into research design and validation processes, scientific experts ensure their work withstands the exacting scrutiny of both scientific peer review and judicial gatekeeping. As legal standards continue to evolve, the integration of rigorous scientific methodology with legal admissibility requirements remains essential for the advancement of forensic science and the administration of justice.

The Daubert Standard provides a systematic framework for a trial court judge to assess the reliability and relevance of expert witness testimony before it is presented to a jury [10]. Established in the 1993 U.S. Supreme Court case Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals Inc., this standard transformed the legal landscape by assigning trial judges a definitive "gatekeeping" role for scientific evidence [10] [3]. This marked a significant departure from the previous Frye Standard (Frye v. United States, 1923), which focused primarily on whether the scientific evidence was "generally accepted" in the relevant scientific community [1] [5]. The Daubert decision held that the Federal Rules of Evidence, particularly Rule 702, had superseded the Frye test, shifting the inquiry from general acceptance to a more nuanced analysis of the reliability and relevance of the expert's methodology [3] [5]. For forensic science researchers and drug development professionals, understanding this framework is essential for ensuring that their expert testimony and scientific evidence meet the court's rigorous admissibility standards.

The Daubert ruling was further refined by two subsequent Supreme Court cases, General Electric Co. v. Joiner (1997) and Kumho Tire Co. v. Carmichael (1999). Together, these three cases are often called the "Daubert Trilogy" [10] [3]. Joiner established that appellate courts should review a trial judge's decision to admit or exclude expert testimony under an "abuse of discretion" standard [3], while Kumho Tire expanded the Daubert standard's application to include non-scientific expert testimony based on technical or other specialized knowledge [10] [3]. This expansion means that the framework applies not only to traditional scientists but also to engineers, forensic examiners, and other specialists whose testimony is rooted in skill- or experience-based observation [3].

The Core Five Factors: A Detailed Analysis

The Daubert standard outlines five flexible factors to help judges evaluate the reliability of an expert's methodology. These factors are not a rigid checklist but rather a guide for a holistic assessment of scientific validity [20].

Factor 1: Empirical Testing and Testability

The first, and arguably foremost, factor asks whether the expert's technique or theory can be and has been tested [10] [14]. The scientific method is grounded in forming hypotheses and conducting experiments to prove or falsify them. A reliable technique or theory must, therefore, be capable of being tested and empirically assessed for reliability [3] [4]. The court in Daubert emphasized that a key question will be whether the expert's methodology can be (and has been) tested [1]. For researchers, this means that the principles underlying their conclusions must be founded on falsifiable hypotheses that can be subjected to empirical validation. In practice, a judge's focus under this factor is on the expert's methodology rather than the conclusions themselves, ensuring the opinion is derived from sound scientific principles applied reliably to the case's facts [3] [14].

Factor 2: Peer Review and Publication

The second factor considers whether the method or theory has been subjected to peer review and publication [10]. Peer review is the process by which other experts in the same field evaluate scientific work before it is published [3]. This process helps ensure that only valid, reliable research is published by providing a mechanism for scrutiny and feedback [3] [14]. Publication in a peer-reviewed journal is not an absolute requirement for admissibility, but it is a significant indicator that the methodology has been vetted by the scientific community. It suggests that the technique or theory has been evaluated for methodological soundness, which bolsters its reliability. The absence of peer review, while not automatically disqualifying, is a relevant consideration for the court in determining whether the expert is presenting "good science" [3].

Factor 3: Known or Potential Error Rate

The third factor examines the known or potential error rate of the technique [10]. Understanding a method's accuracy is fundamental to assessing its reliability. This involves examining the methodology for flaws that may produce errors and, if possible, obtaining a quantitative or numerical error rate [3]. The Daubert Court highlighted that empirical proof of efficacy, including a known error rate, is essential for determining whether a scientific method is valid [13]. For many forensic disciplines, this has proven challenging, as rigorous error rate studies have historically been lacking [13]. For researchers, this factor necessitates a thorough understanding of their methods' statistical validation and performance metrics. If an expert cannot provide an error rate, the court may find it impossible to analyze the likelihood of error, potentially rendering the evidence inadmissible [3].

Factor 4: Existence and Maintenance of Standards

The fourth factor investigates the existence and maintenance of standards and controls controlling the technique's operation [10]. The consistent application of a methodology is a hallmark of reliability. The presence of explicit, documented standards that guide the application of a technique, as well as protocols for maintaining those standards, increases the likelihood that a court will deem the methodology reliable [3] [14]. This factor assesses whether the field has established operational protocols, certification requirements, and quality assurance procedures to ensure the method is applied consistently and correctly. For forensic science laboratories, this often relates to their accreditation status and adherence to established industry standards, which help minimize bias and ensure the reproducibility of results [13].

Factor 5: General Acceptance

The fifth and final factor considers whether the technique or theory has attracted widespread acceptance within a relevant scientific community [10]. This factor incorporates the core of the older Frye standard into the more flexible Daubert analysis [1] [5]. While "general acceptance" is no longer the sole determinant of admissibility, it remains an important factor [3]. Widespread acceptance within the relevant field suggests that the methodology has withstood the scrutiny of the broader scientific community. However, novel scientific methods are not automatically inadmissible simply because they are not yet universally accepted. The court must weigh this factor alongside the others, recognizing that some new but reliable methods may not yet be generally accepted [20] [3].

Diagram 1: The Daubert Factor Evaluation Workflow. This flowchart illustrates the sequential judicial inquiry into the admissibility of expert testimony based on the five Daubert factors. A negative assessment at any stage can lead to a finding of unreliability.

Daubert in Action: Application in Forensic Science & Research

The Daubert standard has profound implications for forensic science research and practice. Courts have admitted a wide array of forensic evidence without requiring rigorous statistical proof of error rates, creating a dilemma between ensuring scientific validity and the practical demands of the justice system [13]. For many forensic disciplines, the central mission is to "match" an unknown item of evidence to a specific known source, a process known as individualization [13]. Yet, a landmark 2009 report by the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) concluded that, with the exception of nuclear DNA analysis, no forensic method has been rigorously shown to consistently and with a high degree of certainty support conclusions about individualization [13]. This critique has spurred efforts to develop statistical methods to measure error rates in these disciplines.

Case Study: Fingerprint Evidence and Daubert

Fingerprint evidence, long considered infallible in popular culture, has faced significant Daubert challenges regarding its scientific validity [21]. When analyzed under the five factors, specific issues emerge:

- Testing & Error Rate: While extensively used, some argue fingerprint analysis requires more rigorous scientific validation. Human error remains a significant concern, and although examiners are generally accurate, documented errors occur [21].

- Standards: The field has established standards, but their consistency and application vary widely among jurisdictions and practitioners [21].

- General Acceptance: Despite being widely accepted in courts, its foundational validity is increasingly questioned, leading to defense challenges [21].

This scrutiny underscores the need for ongoing research and validation in even the most established forensic fields.

Implementing Rigor: Blind Proficiency Testing

A cutting-edge approach to addressing Daubert's requirements, particularly for error rates, is the implementation of blind proficiency testing [13]. The Houston Forensic Science Center (HFSC) has pioneered such a program in six disciplines, including toxicology, firearms, and latent prints [13]. In blind testing, mock evidence samples are introduced into the ordinary workflow without the analysts' knowledge. This approach provides several key advantages for researchers and laboratories:

- Real-World Error Rate Data: It generates empirical data on the efficacy of the forensic testing process as it is actually practiced, providing the statistical foundation called for in Daubert [13].

- Process Quality Control: It tests the entire system, from evidence packaging and storage to testing and reporting, identifying weaknesses beyond analytical error [13].

- Foundational and Applied Validity: It helps establish both the "foundational validity" of a discipline as a whole and "validity as applied" within a specific laboratory [13].

Table 1: Key Research Reagents & Methodologies for Daubert Compliance

| Item/Methodology | Primary Function in Research | Role in Satisfying Daubert Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Blind Proficiency Testing | Introducing mock samples into a laboratory's normal workflow to objectively assess analyst performance and methodological reliability. | Directly addresses Factor 3 (Error Rate) by generating empirical data on method and practitioner accuracy. Also informs Factor 4 (Standards) by testing the robustness of existing protocols [13]. |

| Validation Studies | Conducting rigorous experiments to demonstrate that a method is consistently capable of producing accurate and reproducible results for its intended purpose. | Core to Factor 1 (Testing) and Factor 3 (Error Rate). Provides the scientific foundation that proves a method's reliability before it is applied in casework [13]. |

| Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) | Documented, step-by-step instructions that ensure a method or technique is performed consistently and correctly by all personnel. | The primary mechanism for satisfying Factor 4 (Existence of Standards). SOPs provide the documented controls that prove a method is applied reliably [3] [14]. |

| Peer-Reviewed Publication | Submitting research findings and methodological descriptions to scholarly journals for critical evaluation by independent experts in the field. | The definitive process for fulfilling Factor 2 (Peer Review). Publication demonstrates that the methodology has been vetted and accepted by the broader scientific community [10] [3]. |

The Researcher's Protocol: Preparing for a Daubert Challenge

For scientists and researchers, the prospect of a Daubert challenge—a legal motion to exclude expert testimony—requires proactive preparation. The following protocol outlines a systematic approach to ensuring your work meets the Daubert standard.

Pre-Trial Methodology Validation

1. Establish a Foundation of Reliability: Before any testimony is contemplated, the underlying research methodology must be validated. This involves:

- Conducting Robust Validation Studies: Design and execute studies that explicitly test your method's accuracy, precision, and reproducibility. Document all procedures and results meticulously [13].

- Determine and Document Error Rates: Actively research and quantify your method's known or potential error rate. If a specific numerical rate is unavailable, be prepared to discuss the sources of potential error and the controls in place to mitigate them [3] [13].

- Implement and Adhere to SOPs: Develop and follow detailed Standard Operating Procedures. Maintain records of protocol versions, training on these protocols, and strict adherence to them in practice [3].

2. Seek Peer Review and Publication: Actively submit your methodologies and validation studies for peer review. Publication in a respected journal is powerful evidence that your work is considered reliable within your scientific community, directly addressing Daubert Factor 2 [3] [14].

3. Stay Informed on General Acceptance: Maintain awareness of the current consensus and debates within your field regarding your techniques. Be prepared to articulate the degree of acceptance and to discuss respectfully any recognized controversies or limitations [21].

The Daubert Hearing and Expert Testimony

A Daubert hearing is a pre-trial proceeding where the judge evaluates the admissibility of expert testimony. To effectively present your work:

- Communicate Methodology Clearly: Be prepared to explain your methodology, its underlying principles, and the steps taken to ensure its reliability in terms accessible to a non-specialist judge [14].

- Present Supporting Documentation: Bring all relevant materials, including publications, validation study data, SOPs, and curriculum vitae, to demonstrate the rigor of your work and your own qualifications [14].

- Defend Your Error Rate Analysis: Clearly explain how error rates were determined or estimated and contextualize what the rates mean for the reliability of your conclusions [3] [13].

Table 2: A Researcher's Checklist for Daubert Preparedness

| Daubert Factor | Pre-Trial Research Phase | Documentation & Evidence for Court |

|---|---|---|

| Testing & Testability | Conduct and document rigorous validation studies. Ensure hypotheses are falsifiable and methods are empirically sound. | Copies of validation study protocols, raw data, and results analysis. Ready explanation of the scientific method applied. |

| Peer Review | Submit work to reputable, peer-reviewed journals. Participate in peer review of others' work in your field. | PDFs of published papers. List of presentations at scientific conferences. |

| Error Rate | Actively research, calculate, and monitor the method's error rate through proficiency testing. | Statistics from internal or external proficiency tests. Literature citing error rates for the method. |

| Existence of Standards | Develop, maintain, and rigorously follow detailed SOPs. Seek laboratory accreditation. | Copies of relevant SOPs. Certificates of accreditation (e.g., ISO, ASCLD/LAB). Training records. |

| General Acceptance | Stay current with scientific literature and professional guidelines in your field. | Literature reviews, professional white papers, and survey data showing acceptance. |

Diagram 2: The Scientific and Judicial Validation Ecosystem. This diagram depicts the critical feedback loops between a researcher, the scientific community, and the court. The researcher must engage with peer review and proficiency testing to generate the integrated evidence required by the judicial gatekeeper.

The Five Daubert Factors provide a comprehensive, systematic framework for judges to assess the reliability of expert testimony. For forensic science researchers and drug development professionals, this legal standard is not merely a procedural hurdle but a powerful articulation of the core principles of sound science: testability, peer scrutiny, quantifiable performance, operational standards, and community consensus. The ongoing integration of rigorous practices like blind proficiency testing is closing the gap between legal requirements and scientific practice, providing the empirical data needed to support the forensic disciplines. By embedding the Daubert factors directly into their research design and validation processes, scientists can ensure their work withstands judicial scrutiny and contributes to the administration of justice based on robust, reliable, and admissible scientific evidence.

Applying Daubert: Ensuring Your Scientific Methodology Meets Legal Standards

Within the framework of the Daubert standard, the principle of testability stands as the foundational gatekeeper for the admissibility of scientific evidence in legal proceedings. For forensic science research, demonstrating that a technique or theory can be and has been empirically tested is paramount. This guide provides researchers and drug development professionals with a detailed framework for embedding robust testability into their experimental designs, ensuring their methodologies meet the rigorous demands of the Daubert criteria for reliability. We outline specific experimental protocols, data presentation standards, and validation workflows tailored to the forensic context.

The Daubert Standard and the Primacy of Testability

The Daubert standard, established by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1993, assigns trial judges the role of "gatekeepers" who must ensure that all expert testimony, including scientific evidence, is not only relevant but also reliable [4] [10]. This standard superseded the older Frye standard, which focused solely on whether a method was "generally accepted" in the relevant scientific community [3].

The Court provided a non-exhaustive list of factors to guide judges in assessing reliability, the first of which is testability [4] [3]. The Court emphasized that a cornerstone of the scientific method is the formulation of hypotheses that can be tested and potentially falsified through experimentation [4]. For a scientific theory or technique to be considered valid "scientific knowledge," its proponents must demonstrate that it is the product of sound "scientific methodology" [4]. In practice, this means that the methodology underlying expert testimony must be capable of being challenged and subjected to empirical verification. As the Court later clarified in General Electric Co. v. Joiner, an expert's conclusion must be connected to existing data by more than just the "ipse dixit" (the unsupported say-so) of the expert [3]. The reliability of the principles and methods used must be shown through testing.

Core Components of a Testable Protocol for Forensic Research

For forensic research to satisfy Daubert's testability factor, the experimental design must be structured, transparent, and repeatable. The following components are essential.

Table 1: Core Components of a Daubert-Compliant Testable Protocol

| Component | Description | Daubert Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Falsifiable Hypothesis | A clear, specific statement that can be proven false through experimentation. | The foundation of testability; distinguishes scientific inquiry from subjective belief [4]. |

| Controlled Experimentation | A study design that isolates the variable of interest and controls for confounding factors. | Provides a clear causal link between the methodology and the results, demonstrating the technique's validity [4]. |

| Defined Operational Parameters | Precise specifications of the methodology, including equipment, reagents, and environmental conditions. | Allows for the technique to be reliably replicated by other researchers, a key indicator of its reliability [3]. |

| Objective Outcome Measures | Quantitative, empirically verifiable data points as the primary results, rather than subjective interpretation. | Reduces potential bias and allows for the calculation of error rates, another key Daubert factor [10] [3]. |

| Independent Replication | The protocol is documented with sufficient detail to allow other research teams to repeat the experiment. | Peer review and independent verification are strong indicators of a method's scientific validity [4] [10]. |

Development of a Falsifiable Hypothesis

A well-constructed hypothesis is the cornerstone of testability. For a forensic researcher, this means moving from a general question to a specific, testable prediction.

- Example (Forensic Toxicology): Instead of asking "Does Drug X impair driving?", a testable hypothesis would be: "Subjects administered a 10 mg dose of Drug X will demonstrate a statistically significant increase (p < 0.05) in lane deviation frequency in a high-fidelity driving simulator compared to subjects administered a placebo."

Experimental Design for Validation

The design must validate both the underlying scientific principle and its specific forensic application.

- Example Protocol: Validating a Novel Assay for Drug Detection

- Objective: To determine the sensitivity and specificity of a new Mass Spectrometry (MS) method for detecting Synthetic Cannabinoid JWH-018 in human serum.

- Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Spike known quantities of JWH-018 standard (e.g., 0.1, 0.5, 1.0, 5.0 ng/mL) into drug-free human serum. Include a minimum of 10 replicates per concentration.

- Blinding: Code all samples and intersperse them with true negative controls (n=20) by a technician not involved in the MS analysis.

- Instrumental Analysis: Analyze all samples using the novel MS method according to a standardized operating procedure (SOP) detailing ionization mode, fragment ions monitored, and chromatographic conditions.

- Data Analysis: Compare the results from the MS analysis against the known sample identities to calculate the false positive rate, false negative rate, and the lower limit of detection (LLOD) and quantification (LLOQ).

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key stages of this experimental validation process.

Quantitative Metrics and Data Presentation for the Court

Presenting quantitative data in a clear, standardized manner is critical for demonstrating testability and reliability to the court. Judges assessing Daubert motions require concise, comparable data on a method's performance.

Table 2: Key Quantitative Metrics for Demonstrating Reliability under Daubert

| Metric | Calculation | Interpretation in Daubert Context |

|---|---|---|