Siamese Networks for Authorship Verification: From Theory to Practical Applications in Biomedical Research

This comprehensive review explores the practical application of Siamese neural networks for authorship verification tasks, with particular relevance for researchers and drug development professionals.

Siamese Networks for Authorship Verification: From Theory to Practical Applications in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores the practical application of Siamese neural networks for authorship verification tasks, with particular relevance for researchers and drug development professionals. The article covers foundational concepts of Siamese network architecture and their advantages for stylistic analysis, detailed methodological implementations including graph-based and transformer-based approaches, crucial optimization strategies for efficient training, and comparative validation against traditional methods. By synthesizing current research and practical considerations, this guide provides actionable insights for implementing authorship verification systems in research integrity, documentation analysis, and collaborative writing assessment in scientific contexts.

Understanding Siamese Networks: Core Architecture and Advantages for Authorship Analysis

What Are Siamese Neural Networks? Parallel Architecture and Weight Sharing Mechanisms

A Siamese Neural Network (SNN) is a specialized class of neural network architectures that contains two or more identical sub-networks [1] [2]. The term "identical" means these sub-networks have the same configuration with the same parameters and weights [3]. Parameter updating is mirrored across both sub-networks [3]. This architecture is designed to compare two input vectors by processing them in tandem through these identical networks to compute comparable output vectors [1]. The fundamental principle behind Siamese networks is their ability to learn a similarity function rather than classifying inputs into predefined categories [4] [5]. This makes them particularly valuable for verification tasks, one-shot learning, and scenarios where the relationship between data points is more important than absolute classification [2].

The motivation for Siamese networks arises from tasks requiring comparison, such as verification and one-shot learning, where the objective is to assess whether two inputs are similar or belong to the same class, even with limited examples per class [6]. Unlike conventional convolutional neural networks (CNNs) that use a softmax layer for classification, SNNs pass the difference of outputs from dense layers through a similarity metric [6]. Originally introduced by Bromley et al. for signature verification, SNNs have since been applied to various domains requiring pairwise input distinction [6].

Architectural Framework and Weight Sharing

Core Architectural Components

The Siamese network architecture consists of several key components that work together to enable similarity learning:

- Identical Sub-networks: Two or more subnetworks with exactly the same architecture [2] [3]. These are often called "twin networks" [1].

- Shared Weights: The identical subnetworks share the same weights and parameters during training and inference [2]. This weight sharing ensures that both inputs are processed through the same transformation [6].

- Feature Extraction: Each subnetwork processes one input and produces an output embedding or feature vector [2] [6]. For image data, convolutional neural networks are typically employed, while recurrent networks are used for sequential data [6].

- Similarity Function: A distance metric that compares the feature vectors from the subnetworks [2]. Common functions include Euclidean distance and cosine similarity [2].

The Weight Sharing Mechanism

Weight sharing is the defining characteristic of Siamese networks [2]. This mechanism ensures that similar inputs are mapped close to each other in the feature space by binding the weights of the subnetworks together [6]. During training, the gradients are computed for each subnetwork, and the weight updates are synchronized across all identical subnetworks [3]. This shared parameterization forces the network to learn representations that are effective for comparison rather than for individual classification tasks [6].

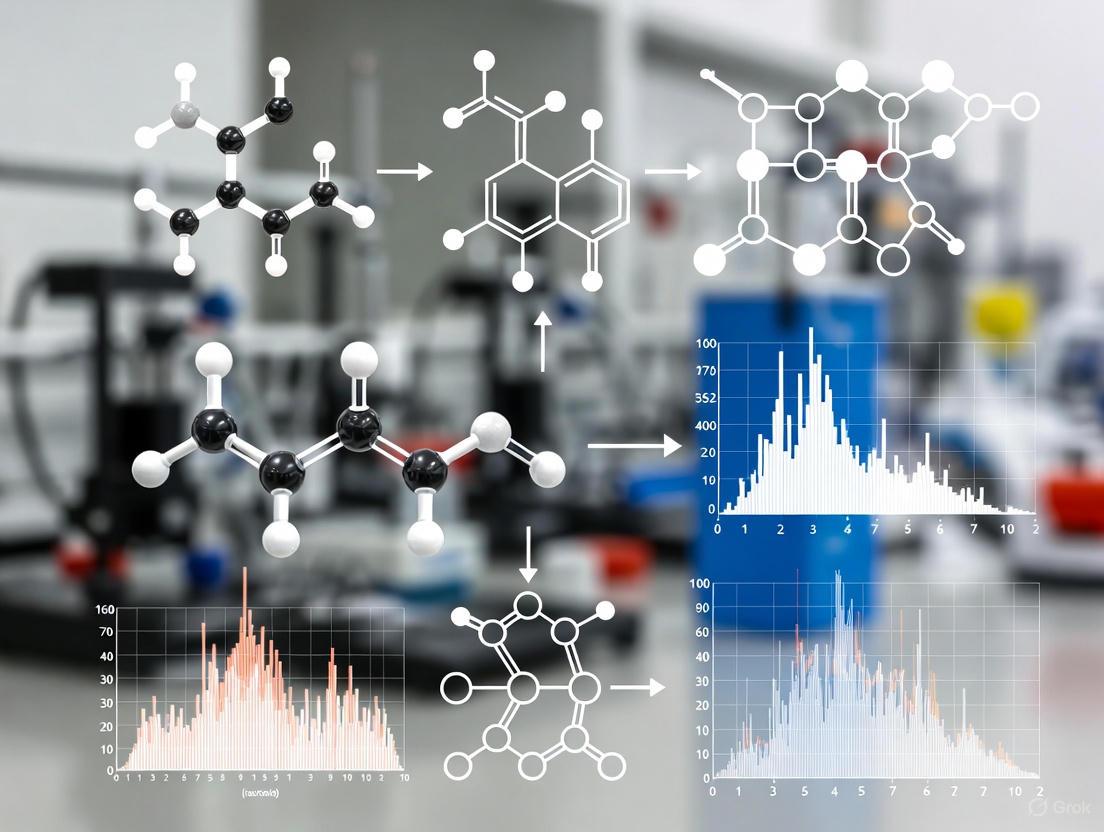

The following diagram illustrates the complete architecture and data flow of a Siamese network:

Distance Metrics and Similarity Functions

After feature extraction, the SNN compares the embeddings using a similarity function [2]. This function quantifies how similar or dissimilar the inputs are based on their feature representations [2]. The most common distance metrics include:

- Euclidean Distance: Measures the straight-line distance between two points in the embedding space [2]. Calculated as (D(x1, x2) = \sqrt{\sum{}^{}(x{1i} - x_{2i})^2}) [2]. A smaller Euclidean distance indicates greater similarity between the inputs [2].

- Cosine Similarity: Measures the cosine of the angle between two vectors in the embedding space [2]. Calculated as (\text{cosine_similarity}(x1, x2) = \frac{x1 \cdot x2}{\|x1\|\cdot\|x2\|}) [2]. A cosine similarity close to 1 indicates that the vectors are aligned and thus similar [2].

Table 1: Comparison of Distance Metrics in Siamese Networks

| Metric | Calculation | Range | Optimal Value | Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Euclidean Distance | (D = \sqrt{\sum(x{1i} - x{2i})^2}) | [0, ∞) | 0 (identical) | Face verification, signature verification [2] |

| Cosine Similarity | (\frac{x1 \cdot x2}{|x1|\cdot|x2|}) | [-1, 1] | 1 (identical) | Document similarity, semantic textual similarity [2] |

| Mahalanobis Distance | (\sqrt{(x1-x2)^T M (x1-x2)}) | [0, ∞) | 0 (identical) | Learned metrics, specialized applications [1] |

Loss Functions for Similarity Learning

Training Siamese networks requires specialized loss functions designed for similarity learning rather than conventional classification [1] [3]. The following table summarizes the key loss functions used in Siamese networks:

Table 2: Loss Functions for Training Siamese Neural Networks

| Loss Function | Mathematical Formulation | Input Structure | Key Parameters | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contrastive Loss [4] [2] [6] | (L = \frac{1}{2}[(1-y)D^2 + y \max(0, m-D)^2]) | Image pairs | Margin (m), Distance (D), Label (y) | Simple pairwise comparison, effective for verification tasks |

| Triplet Loss [1] [5] [3] | (L = \max(d(a,p) - d(a,n) + \text{margin}, 0)) | Anchor, Positive, Negative triplets | Margin, Distance function | Better separation between classes, improved embedding space organization |

| Binary Cross-Entropy [4] | (L = -(y\log(p) + (1-y)\log(1-p))) | Image pairs with similarity label | Predicted probability (p), Label (y) | Traditional approach, interpretable outputs |

The learning goal for these loss functions can be formally expressed as:

[ \begin{aligned} \delta(x^{(i)}, x^{(j)}) = \begin{cases} \min \|\operatorname{f}\left(x^{(i)}\right)-\operatorname{f}\left(x^{(j)}\right)\|\,, & i=j \ \max \|\operatorname{f}\left(x^{(i)}\right)-\operatorname{f}\left(x^{(j)}\right)\|\,, & i\neq j \end{cases} \end{aligned} ]

Where (i,j) identify different inputs, and (\operatorname{f}(\cdot)) represents the network's transformation [1].

The following diagram illustrates the triplet loss mechanism, which has become particularly important for effective similarity learning:

Experimental Protocol for Authorship Verification

Problem Formulation and Dataset Preparation

For authorship research, the Siamese network is trained to verify whether two handwriting samples belong to the same author [7]. The network learns to compare and analyze unique characteristics of handwriting and writing style [7]. This approach generates powerful discriminative image features (embeddings) that enable qualitative classification of the author [7].

Dataset Collection and Preprocessing:

- Source: Utilize historical manuscript collections or benchmark datasets like the IAM dataset for handwritten text [7].

- Data Partitioning: For each known author, gather multiple writing samples. Split into reference samples (exemplars) and verification samples.

- Image Preprocessing:

- Pair Generation: Create positive pairs (same author) and negative pairs (different authors) for training [4].

Network Architecture and Training Configuration

Network Architecture Specifications:

- Feature Extraction Backbone: Implement convolutional layers as specified in SigNet or similar architectures [3]:

- Embedding Dimension: 128-dimensional output space [3]

- Distance Metric: Euclidean distance for similarity measurement [2]

Training Protocol:

- Loss Function: Triplet loss with margin parameter of 0.2 [1] [5]

- Optimizer: Adam with learning rate of 0.0001

- Batch Construction: Form triplets with careful selection of hard negatives

- Training Duration: 50-100 epochs with early stopping

- Validation: Monitor accuracy on held-out author pairs

Evaluation Metrics and Interpretation

Table 3: Performance Metrics for Authorship Verification Experiments

| Metric | Calculation | Target Value | Interpretation in Authorship Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Verification Accuracy | (\frac{\text{Correct Predictions}}{\text{Total Predictions}}) | >90% | Overall system reliability |

| False Acceptance Rate (FAR) | (\frac{\text{Incorrect Same-Author}}{\text{Total Different-Author}}) | <5% | Security risk: accepting forgeries |

| False Rejection Rate (FRR) | (\frac{\text{Incorrect Different-Author}}{\text{Total Same-Author}}) | <10% | Usability: rejecting genuine authors |

| Equal Error Rate (EER) | Point where FAR = FRR | Minimize | Balanced system performance |

| ROC-AUC | Area Under ROC Curve | >0.95 | Discriminative power of the model |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Siamese Network Research

| Research Reagent | Specification/Function | Application in Authorship Research |

|---|---|---|

| ICDAR 2011 Dataset [4] [3] | Dutch signatures (genuine and fraudulent) | Benchmarking signature verification algorithms |

| IAM Handwriting Database [7] | Handwritten English text from multiple writers | Training and evaluation for writer identification |

| PyTorch/TensorFlow [4] | Deep learning frameworks with Siamese network implementations | Model development and experimentation |

| Graph Isomorphism Network (GIN) [8] | Graph encoder with superior structural recognition | Advanced graph-based document analysis |

| Data Augmentation Pipeline [8] | Controlled random noise, affine transformations | Increasing dataset diversity and model robustness |

| Triplet Mining Strategies | Semi-hard negative mining, distance-weighted sampling | Improving training efficiency and embedding quality |

| t-SNE/UMAP Visualization | Dimensionality reduction for embedding visualization | Qualitative assessment of feature space separation |

| Optical Character Recognition | Text extraction and normalization | Preprocessing for content-aware authorship analysis |

Advanced Applications in Authorship Research

Historical Document Analysis

The proposed approach has been successfully applied to verify possible autographs of Zhukovsky among manuscripts of unknown authors [7]. This demonstrates the potential of Siamese networks for historical document analysis and attribution studies where training examples are limited [7]. The method can effectively operate with a small number of exemplar handwriting samples, making it particularly valuable for historical research where extensive writing samples may not be available [7].

Multi-Scale Document Analysis

Recent advances in Siamese networks include multi-branch and hybrid architectures that integrate attention mechanisms [6]. For complex authorship problems, these architectures can process documents at multiple scales: individual character formation, word-level features, and document-level spatial distributions [8]. The cross-network and cross-view contrastive learning objectives optimize document representations by leveraging complementary information between different views [8].

Implementation Considerations and Limitations

While Siamese networks offer significant advantages for authorship research, several practical considerations must be addressed:

- Computational Intensity: Siamese networks can be computationally intensive, especially during training with large numbers of pairs or triplets [2].

- Data Pair Design: Performance depends heavily on careful design and selection of input pairs [2]. Creating balanced and meaningful pairs for training is crucial [2].

- Margin Selection: The margin parameter in contrastive and triplet loss requires careful tuning for optimal performance [5].

- Generalization: Models trained for one authorship verification task may not generalize well to different historical periods or writing styles without fine-tuning [5].

For researchers implementing Siamese networks for authorship studies, it is recommended to start with established architectures like SigNet for signature verification [3] and gradually incorporate domain-specific adaptations for more specialized applications in historical document analysis.

Authorship verification, the task of determining whether two texts were written by the same author, represents a significant challenge in digital forensics, literary analysis, and security applications. Traditional classification-based approaches to authorship analysis struggle with real-world scenarios where the potential author may not be part of the initial training set—a limitation known as the open-set problem [9]. Siamese Networks address this fundamental limitation by learning a general notion of stylistic similarity between texts rather than simply classifying them into predefined author categories [9] [10].

The core innovation of Siamese Networks lies in their ability to compare writing styles through a learned similarity metric, enabling them to verify authorship even for authors completely unseen during training. This makes them particularly valuable for practical authorship research, where the number of potential authors may be large or unknown in advance [9]. By embodying a similarity-based paradigm rather than a conventional classification approach, Siamese Networks blur the boundaries between traditional authorship attribution methods and offer superior performance in open-set scenarios [9].

Architectural Foundations of Siamese Networks

Core Components and Parameter Sharing

Siamese Networks employ a distinctive architecture consisting of two identical subnetworks that process paired inputs simultaneously. These twin networks share identical parameters and weights, ensuring that similar inputs are mapped to similar locations in the feature space [11]. The fundamental components include:

- Twin subnetworks: Two or more identical neural networks with mirrored configurations

- Weight sharing: Synchronized parameter updates across both subnetworks during training

- Distance metric layer: Computes the degree of similarity or dissimilarity between the extracted features

- Energy function: Generates the final similarity score for the input pair [9]

This parameter sharing is crucial as it reduces the number of trainable parameters and ensures that two similar texts processed through the same network will generate comparable output representations. The shared weights act as a feature extractor that learns to encode stylistically relevant information from the input texts [11].

Distance Metrics and Energy Functions

The choice of distance metric significantly influences the network's ability to discriminate between authors. Research has shown that different energy functions interact unexpectedly with the size of the author candidate pool [9]. The most commonly employed metrics include:

- L1 distance (Manhattan distance): Often used as a baseline similarity measure

- Cosine similarity: Measures the angular difference between feature vectors

- Euclidean distance: Straight-line distance between feature representations

In authorship verification tasks, studies have demonstrated that while there is no clear difference between L1 distance and cosine similarity in basic verification tasks, cosine similarity substantially outperforms in scenarios requiring selection among multiple candidate authors [9].

Quantitative Performance in Authorship Verification

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Authorship Verification Methods

| Method | Dataset | Accuracy | Evaluation Scenario |

|---|---|---|---|

| Siamese Network (L1 distance) | PAN (cross-topic) | 0.980 | Verification with 1000 training authors [9] |

| Siamese Network (cosine similarity) | PAN (cross-topic) | 0.978 | Verification with 1000 training authors [9] |

| Graph-Based Siamese Network | PAN@CLEF 2021 | 90%-92.83% | Open-set scenario (AUC ROC, F1, Brier score) [10] |

| Traditional Similarity-Based (Koppel et al.) | Various | Lower than Siamese | One-shot evaluation [9] |

| Unmasking Method | Long texts (~500K words) | 95.7% | Closed-set scenario [10] |

| Unmasking Method | Short texts (~10K words) | ~77% | Cross-topic scenario [10] |

Table 2: Siamese Network Performance Across Different Training Set Sizes

| Training Authors | Verification Accuracy | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 100 | Very low | Insufficient to learn general notion of similarity [9] |

| 1,000 | 0.980 (Siam-L1), 0.978 (Siam-cos) | Substantial improvement in performance [9] |

| 10,000 | No improvement over 1,000 | Diminishing returns observed [9] |

The quantitative evidence demonstrates that Siamese Networks achieve competitive performance against state-of-the-art methods, particularly in challenging open-set scenarios where authors are unseen during training [9] [10]. The graph-based Siamese approach has shown particularly promising results, achieving average scores between 90% and 92.83% across multiple evaluation metrics including AUC ROC, F1, Brier score, F0.5u, and C@1 when trained on both "small" and "large" corpora [10].

Experimental Protocols for Authorship Verification

Data Preparation and Text Representation

The first critical step in implementing Siamese Networks for authorship verification involves appropriate text representation and pair construction:

Text Representation Strategies:

- Character n-grams: Particularly space-free character 4-grams have proven effective for capturing stylistic patterns [9]

- Graph-based representations: Construct co-occurrence graphs based on POS labels of words to capture structural information [10]

- Syntactic features: Utilize POS tags and syntactic patterns that are more topic-invariant [10]

- Lexical features: Word n-grams, function words, and vocabulary richness indicators

Pair Generation:

- Positive pairs: Text pairs known to be from the same author

- Negative pairs: Text pairs from different authors

- Balanced sampling: Ensure approximately equal numbers of positive and negative pairs to avoid class imbalance [11]

For graph-based representations, researchers have developed three primary strategies of varying complexity: "short," "med," and "full," which differ in graph complexity and computational requirements [10]. The co-occurrence based on POS representation has shown particular promise by capturing syntactic writing patterns that are difficult to consciously manipulate [10].

Network Architecture Configuration

Implementing an effective Siamese Network requires careful architectural decisions:

Siamese Network Architecture for Authorship Verification

The architectural configuration involves:

Subnetwork Design:

Feature Dimension:

- Hidden layers typically range from 256 to 512 dimensions [11]

- Final embedding size should balance discriminative power and computational efficiency

Distance Computation:

- Implement either L1 distance or cosine similarity layers

- The choice significantly affects performance in different evaluation scenarios [9]

Training Methodology and Loss Functions

The training process requires specialized loss functions designed for similarity learning:

Contrastive Loss:

- Formula:

(1-Y) × 0.5 × X² + Y × 0.5 × (max(0, m-X))²[11] - Where Y is the prediction, X is the Euclidean distance between network outputs, and m is a margin parameter

- Minimizes distance for positive pairs while maximizing it for negative pairs

- Formula:

Triplet Loss:

- Formula:

max(0, d(A,P) - d(A,N) + alpha)[11] - Uses triplets of anchor (A), positive (P), and negative (N) examples

- Creates relative distance constraints rather than absolute ones

- Formula:

For authorship verification, research indicates that triplet loss generally outperforms contrastive loss for complex stylistic distinctions, as it learns decision boundaries more effectively by considering positive and negative examples simultaneously [11]. The margin parameter (m or alpha) should be carefully tuned to the specific dataset characteristics.

Evaluation Protocols

Proper evaluation of authorship verification systems requires distinct protocols:

Closed-Set Evaluation:

- Authors in test set are also present in training data

- Measures performance on known authors

One-Shot/Open-Set Evaluation:

- Authors in test set are completely disjoint from training authors [9]

- More representative of real-world scenarios

- Tests the model's ability to generalize its notion of stylistic similarity

Cross-Topic Evaluation:

- Tests robustness to topic variation between texts by the same author

- Critical for real-world applicability where topics may vary significantly

The one-shot evaluation paradigm is particularly important, as it most closely mimics real-world forensic applications where the suspect author may not be in any reference database [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Siamese Network-Based Authorship Verification

| Research Reagent | Function | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| PAN Datasets | Standardized evaluation benchmarks | PAN@CLEF 2021 fanfiction dataset [10] |

| Graph Representation Libraries | Convert texts to graph structures | POS taggers, graph construction algorithms [10] |

| Siamese Network Frameworks | Model implementation | Keras, PyTorch with twin architecture support [11] |

| Text Preprocessing Tools | Feature extraction | NLTK, SpaCy for linguistic preprocessing [10] |

| Evaluation Metrics | Performance assessment | AUC ROC, F1, Brier score, F0.5u, C@1 [10] |

| Loss Function Implementations | Model optimization | Contrastive loss, triplet loss implementations [11] |

Advanced Applications and Methodological Variations

Graph-Based Siamese Networks

Recent research has demonstrated that representing texts as graphs rather than sequential data can capture structural stylistic patterns that might otherwise be overlooked [10]. The graph-based approach involves:

- Node Definition: Words, phrases, or syntactic elements as graph nodes

- Edge Formation: Connections based on co-occurrence, syntactic relationships, or semantic associations

- Graph Convolutional Networks: Specialized neural networks that operate directly on graph structures

This approach has achieved state-of-the-art performance in cross-topic and open-set scenarios, demonstrating the value of structural stylistic features that remain consistent across topics [10].

Ensemble and Hybrid Approaches

Combining Siamese Networks with traditional stylometric features has shown improved performance:

- Feature Fusion: Integrating graph-based representations with traditional stylometric features [10]

- Architectural Ensembles: Combining multiple Siamese variants with different architectures or input representations

- Threshold Optimization: Adjusting decision boundaries based on validation performance to optimize verification accuracy [10]

These hybrid approaches leverage both the learned similarity metrics of Siamese Networks and the well-established discriminative power of traditional stylometric features.

Visualization of Experimental Workflow

Authorship Verification Experimental Workflow

Siamese Networks represent a paradigm shift in authorship verification by moving from classification-based to similarity-based approaches. Their ability to learn a general notion of stylistic similarity makes them uniquely suited for real-world applications where authors may be unknown during training. The graph-based Siamese architecture in particular has demonstrated state-of-the-art performance in challenging cross-topic and open-set scenarios [10].

Future research directions include developing more interpretable Siamese Networks that can provide explanations for their similarity judgments, integrating multimodal stylistic features, and adapting to cross-lingual authorship verification. As these architectures continue to evolve, they promise to significantly advance the field of computational authorship analysis by providing more flexible, robust, and applicable verification systems.

The experimental protocols outlined in this document provide researchers with a comprehensive framework for implementing and evaluating Siamese Networks for authorship verification, supported by quantitative performance data and methodological details from current literature.

Siamese Neural Networks represent a class of architectures designed to compare and measure similarity between pairs or triplets of input samples. The term "Siamese" originates from the concept of twin neural networks that are identical in structure and share the same set of weights and parameters [12] [5]. Each network processes one input sample, and their outputs are compared to determine similarity or dissimilarity between inputs. This architecture excels in tasks where direct training with labeled examples is limited, as it learns to differentiate between similar and dissimilar instances without requiring explicit class labels [5]. The fundamental motivation behind Siamese networks is to learn meaningful representations of input samples that capture essential features for similarity comparison, making them particularly valuable for few-shot learning scenarios where minimal examples are available for new classes [13].

In the context of authorship research, Siamese networks provide a powerful framework for verifying authorship by learning to distinguish between writing styles based on limited exemplars. This capability addresses significant challenges in digital forensics and literary analysis, where the availability of authenticated writing samples is often constrained. The network's ability to transform complex textual patterns into comparable numerical representations enables researchers to objectively quantify stylistic similarities that might be imperceptible through manual analysis [14].

Core Components of Siamese Networks

Embedding Spaces

Embedding spaces form the foundational component where input data is transformed into lower-dimensional, dense vector representations that preserve semantic relationships. In Siamese networks, each twin network functions as an encoder that projects inputs into this shared embedding space [12] [15]. The primary objective during training is to optimize this embedding space such that similar samples are positioned closer together while dissimilar samples are pushed farther apart. Research by Tokhtakhunov et al. demonstrated that autoencoder-based user embeddings in targeted advertising successfully captured essential user profile characteristics in a lower-dimensional space, achieving an F1 score of 0.75 and ROC-AUC of 0.79 [16].

For authorship verification, the embedding space must capture nuanced stylistic features including syntax, vocabulary richness, punctuation patterns, and structural elements that distinguish authors. The SENSE (Siamese Neural Network for Sequence Embedding) approach, originally developed for biological sequences, showcases how deep learning can learn explicit embedding functions that minimize the difference between alignment distances and pairwise distances in the embedding space [15]. When adapted to textual analysis, this approach can effectively encode writing style signatures that remain consistent across an author's works while differing significantly from other authors.

Distance Metrics

Distance metrics quantitatively measure the separation between embedded representations in the latent space, serving as the mechanism for similarity assessment. These metrics mathematically formalize the concept of "closeness" between feature vectors, with different metrics emphasizing various aspects of the vector relationship [17].

Table 1: Comparison of Distance Metrics in Siamese Networks

| Metric | Formula | Advantages | Limitations | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Euclidean | √Σ(a_i - b_i)² |

Intuitive geometric distance | Sensitive to vector magnitude | General similarity tasks [5] [17] |

| Cosine | 1 - (A·B)/(‖A‖‖B‖) |

Focuses on orientation over magnitude | Ignores magnitude differences | Text similarity, high-dimensional spaces [16] [17] |

| Manhattan | Σ|a_i - b_i| |

Robust to outliers | Less geometrically intuitive | Feature-rich data [5] |

| Jaccard | 1 - |A∩B|/|A∪B| |

Effective for set-like features | Limited to binary representations | Biological sequences [15] |

The selection of an appropriate distance metric significantly influences model performance. For authorship analysis, cosine distance often proves advantageous as it focuses on directional alignment rather than magnitude, making it more sensitive to stylistic patterns while being less affected by document length variations [14] [17].

Similarity Scoring

Similarity scoring translates computed distances into interpretable measures of similarity, typically normalized to a standardized range. The contrastive loss function directly incorporates distance metrics to generate these scores, encouraging the network to produce similar embeddings for genuine pairs and dissimilar embeddings for impostor pairs [12]. In authorship verification, the final similarity score represents the probability or confidence that two documents share the same author.

Advanced implementations may employ triplet loss, which uses three samples (anchor, positive, and negative) simultaneously. The loss function ensures that the distance between the anchor and positive samples is smaller than the distance between the anchor and negative samples by at least a specified margin [5] [17]. This approach has demonstrated superior performance in face recognition and can be equally effective for capturing the subtle nuances of authorial style.

Diagram 1: Siamese network architecture workflow (Max Width: 760px)

Experimental Protocols for Authorship Verification

Data Preparation and Preprocessing

The foundation of reliable authorship verification lies in meticulous data preparation. For social media text analysis, such as tweets, researchers should collect a minimum of 500 documents per author when available, though Siamese networks can function with significantly fewer samples [14]. Each document undergoes preprocessing including tokenization, lowercasing, and punctuation preservation. Feature extraction should encompass lexical features (character n-grams, word n-grams), syntactic features (part-of-speech tags, function word frequencies), and structural features (sentence length, paragraph breaks) [14].

For generating training pairs, create positive pairs (documents from the same author) and negative pairs (documents from different authors) in balanced ratios. In cases of class imbalance, implement stratified sampling to ensure representative distribution of writing styles. The dataset should be partitioned into training (70%), validation (15%), and test (15%) sets, maintaining author disjointness across partitions to prevent data leakage and ensure rigorous evaluation.

Model Architecture Configuration

The Siamese network architecture for authorship verification employs twin encoders with shared weights. Based on the research of Aouchiche et al., a combined CNN-LSTM architecture achieves optimal performance for textual similarity tasks [14]. The configuration should include:

- Embedding Layer: Utilize pre-trained word embeddings (GloVe or FastText) with 300-dimensional vectors, fine-tuned during training.

- Convolutional Layers: Implement three parallel convolutional operations with kernel sizes of 3, 4, and 5, each with 128 filters to capture n-gram features at different granularities.

- LSTM Layers: Stack two bidirectional LSTM layers with 128 units each to model sequential dependencies and long-range stylistic patterns.

- Dense Layers: Include two fully connected layers with 256 and 128 units respectively, with ReLU activation and dropout regularization (rate=0.5).

This architecture achieved 0.97 accuracy in authorship verification experiments on Twitter data, significantly outperforming single-modality approaches [14].

Training Methodology

Model training employs the contrastive loss function with a dynamically adjusted margin parameter. The loss function is formalized as:

[L = (1-Y) \cdot \frac{1}{2} \cdot D^2 + Y \cdot \frac{1}{2} \cdot \max(0, m - D)^2]

Where (Y=0) for genuine pairs, (Y=1) for impostor pairs, (D) represents the computed distance, and (m) is the margin parameter [12]. Training should run for a maximum of 100 epochs with early stopping patience of 10 epochs based on validation loss. Utilize the Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate of 0.001, which decays by 50% after 5 epochs of stagnant validation performance [14].

For challenging authorship tasks with minimal training data, implement triplet loss training with semi-hard negative mining. This approach uses anchor-positive-negative triplets and optimizes the network such that the distance between the anchor and positive is smaller than the distance between the anchor and negative by a specified margin [5] [17].

Evaluation Metrics

Comprehensive evaluation requires multiple metrics to assess different aspects of model performance:

Table 2: Evaluation Metrics for Authorship Verification Systems

| Metric | Formula | Interpretation | Target Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | (TP+TN)/(TP+FP+FN+TN) |

Overall correctness | >0.90 [14] |

| F1-Score | 2·(Precision·Recall)/(Precision+Recall) |

Balance of precision/recall | >0.75 [16] |

| ROC-AUC | Area under ROC curve |

Discrimination ability | >0.79 [16] |

| Lift Score | Capture rate/random rate |

Top percentile performance | 12.9 (top 1%) [16] |

| GAP Metric | Performance difference (IID-OOD) |

Generalization capability | Minimize [18] |

Additionally, report precision, recall, and specificity to provide a comprehensive view of model performance across different decision thresholds. The evaluation should include both in-distribution (IID) and out-of-distribution (OOD) testing to assess generalization capabilities, using the GAP metric to quantify performance differences [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Siamese Network Experiments

| Reagent | Specifications | Function | Exemplars |

|---|---|---|---|

| Text Datasets | IAM Handwriting Database [7], Twitter authorship corpus [14] | Benchmarking and validation | 500+ documents per author |

| Word Embeddings | GloVe (300-dim), FastText | Semantic feature representation | Pre-trained on large corpora |

| Deep Learning Framework | TensorFlow, PyTorch | Model implementation and training | With Siamese architecture support |

| Optimization Library | Adam, SGD with momentum | Model parameter optimization | Learning rate: 0.001 [14] |

| Evaluation Metrics Suite | F1, ROC-AUC, Lift Score | Performance quantification | Multi-metric assessment [16] |

| Computational Resources | GPU with 16GB+ memory | Efficient model training | NVIDIA GeForce GTX 1080 [18] |

Advanced Implementation Strategies

Handling Limited Data Scenarios

Authorship verification often confronts limited training data, particularly when analyzing historical documents or investigating anonymous authors. Few-shot learning approaches address this challenge through specialized training regimens. The C-way k-shot classification framework trains the model to recognize new classes (C) with only a few examples per class (k) [13]. In the most extreme case, one-shot learning uses just a single reference sample per author, mimicking real-world scenarios where only one verified document might be available.

Data augmentation techniques can artificially expand training datasets for authorship analysis. These include semantic-preserving transformations such as synonym replacement (using WordNet), sentence restructuring, and controlled noise injection. However, these techniques must preserve the fundamental stylistic features that characterize an author's writing, requiring careful validation to ensure augmented samples maintain authentic stylistic properties.

Interpretability and Explainability

The "black box" nature of deep learning models presents particular challenges in forensic applications where decision justification is essential. Recent research has developed explanation methods specifically for Siamese networks, such as SINEX (Siamese Networks Explainer) [13]. This post-hoc, perturbation-based approach identifies features with the greatest influence on similarity scores by systematically perturbing input features and measuring output changes.

For authorship analysis, this can reveal which linguistic features (e.g., specific punctuation patterns, word choices, or syntactic constructions) most strongly influence the verification decision. Visualization techniques generate heatmaps that highlight text segments with positive (red) or negative (blue) contributions to the similarity score, enabling researchers to validate whether the model focuses on genuinely stylistic elements rather than topical or functional text components [13].

Diagram 2: Triplet loss training workflow (Max Width: 760px)

Applications in Authorship Research

Siamese networks have demonstrated remarkable effectiveness across diverse authorship verification scenarios. In historical document analysis, researchers successfully applied Siamese networks to verify possible autographs of Zhukovsky among manuscripts of unknown authorship [7]. The model's ability to learn discriminative features from limited exemplars makes it particularly valuable for such applications where authenticated samples are scarce.

For digital forensic applications, Siamese networks can identify authors of anonymous online posts, potentially helping to mitigate malicious activities. The architecture's robustness to topic variations allows it to focus on stylistic patterns rather than content, enabling accurate verification even when documents address completely different subjects [14]. This capability is particularly important in real-world investigations where authors deliberately alter their topics while maintaining consistent stylistic habits.

In literary studies, researchers can employ Siamese networks to settle authorship disputes of anonymous or pseudonymous publications, trace the evolution of an author's style across different periods, and identify potential collaborations or ghostwriting in published works. The quantitative nature of the similarity scores provides objective evidence to supplement traditional qualitative stylistic analysis.

Siamese networks represent a powerful paradigm for authorship verification, combining embedding spaces, distance metrics, and similarity scoring into an integrated framework capable of learning subtle stylistic distinctions from limited data. The twin architecture with shared weights creates comparable feature representations, while contrastive or triplet loss functions optimize the embedding space for discriminative authorship analysis. As research in explainable AI advances, interpretation methods like SINEX will enhance the transparency and forensic validity of these systems, fostering greater acceptance in academic and legal contexts. Future directions include multimodal approaches combining textual, structural, and metadata features, as well as cross-lingual authorship analysis leveraging transfer learning principles.

Siamese Networks represent a specialized class of neural architectures characterized by two or more identical subnetworks that share weights and process different inputs simultaneously. These networks employ contrastive or comparative learning to determine the similarity or relationship between inputs, making them exceptionally valuable for verification, recognition, and similarity detection tasks across diverse domains. While their application in authorship verification has been well-documented, their utility extends significantly into biological, chemical, and security fields [19] [10]. The fundamental strength of Siamese architectures lies in their ability to learn robust embeddings and make accurate comparisons even with limited labeled data, which is particularly valuable in domains where abnormal or positive cases are rare [20].

The core operational principle of Siamese networks involves processing pairs of inputs through identical weight-sharing networks and computing a similarity metric in a shared embedding space. This approach enables them to solve one-shot learning problems, verification tasks, and similarity-based ranking without requiring extensive labeled datasets. As research advances, Siamese networks continue to evolve with enhanced distance metrics, fusion layers, and pruning techniques that improve their efficiency and accuracy across applications [21].

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Siamese Networks Across Application Domains

| Application Domain | Specific Task | Reported Performance | Key Dataset | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Similarity | Drug Discovery & Virtual Screening | Outperformed standard Tanimoto coefficient | MDDR, MUV, DUD | [21] |

| Fetal Health Assessment | Ultrasound Anomaly Detection | 98.6% classification accuracy | 12,400 normal + 767 abnormal ultrasound images | [20] |

| Medical Imaging | Retinal Disease Screening | 94% accuracy | Clinical retinal images | [20] |

| Authorship Verification | Cross-topic text verification | 90-92.83% average scores (AUC ROC, F1, Brier score) | PAN@CLEF 2021 fanfiction corpus | [10] |

| Face Recognition | Kinship Verification | High accuracy (specific metrics not provided) | Family face datasets | [21] |

Table 2: Architectural Advantages of Siamese Networks in Different Domains

| Domain | Data Efficiency | Key Architectural Strength | Limitation Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug Discovery | Moderate | Enhanced similarity measurement with multiple distance layers | Structural heterogeneity in molecules |

| Medical Diagnosis | High (Few-shot learning) | Robust embeddings from limited abnormal samples | Class imbalance (94% normal vs 6% abnormal) |

| Biometrics | High (One-shot learning) | Weight sharing enables verification with minimal examples | Limited training examples per class |

| Authorship Analysis | Moderate | Graph-based representation captures structural writing patterns | Cross-topic generalization |

Molecular Similarity Analysis in Drug Discovery

Application Protocol: Molecular Similarity Screening

Molecular similarity analysis using Siamese networks has revolutionized ligand-based virtual screening (LBVS) in drug discovery by enabling efficient identification of promising drug candidates from large chemical libraries [21]. This approach addresses the critical challenge of structural heterogeneity, where traditional similarity measures like the Tanimoto coefficient (TAN) struggle to capture complex biological similarities between structurally diverse molecules. The implementation follows a structured protocol:

- Step 1: Compound Representation - Convert molecules to structured representations using extended-connectivity fingerprints (ECFP4) or SMILES strings tokenization for transformer-based models.

- Step 2: Pair Selection - Implement similarity-based pairing strategies to reduce computational complexity from O(n²) to O(n) compared to exhaustive pairing.

- Step 3: Model Architecture - Process molecular pairs through identical multi-layer perceptron (MLP) arms with shared weights, then compute similarity using multiple distance metrics.

- Step 4: Enhanced Similarity Measurement - Employ two similarity distance layers followed by a fusion layer to combine their outputs, capturing complementary similarity aspects.

- Step 5: Model Optimization - Apply node pruning based on signal-to-noise ratio to eliminate non-contributing parameters while maintaining model effectiveness.

This protocol has demonstrated superior performance over traditional similarity measures, particularly for structurally heterogeneous molecule classes in benchmark datasets like MDL Drug Data Report (MDDR-DS1, MDDR-DS2, MDDR-DS3), Maximum Unbiased Validation (MUV), and Directory of Useful Decoys (DUD) [21].

Experimental Workflow: Molecular Similarity Assessment

Medical Image Analysis for Fetal Health Assessment

Application Protocol: Few-Shot Fetal Anomaly Detection

Siamese networks address critical challenges in medical imaging, particularly in fetal health assessment where abnormal cases are rare and datasets are severely imbalanced [20]. The implementation leverages few-shot learning capabilities to achieve high accuracy with limited abnormal samples:

Data Acquisition & Preprocessing: Collect ultrasound images from diverse sources (e.g., 12,400 normal samples from Zenodo, 767 abnormal samples from hand-annotated YouTube videos). Resize images to 224×224 pixels, normalize with mean=0.5 and standard deviation=0.5, and apply aggressive data augmentation exclusively to abnormal samples including random horizontal flips (p=0.5), random rotation (±10°), and random translation (≤10% of width/height) to force learning of robust pathological features.

Stratified Cross-Validation: Implement stratified k-fold cross-validation (k=5) with dataset pooling to mitigate source leakage, ensuring each fold contains a representative mix of normal and abnormal cases from both sources, thus preventing model bias toward dataset-specific artifacts.

Multi-Task Learning Architecture: Employ a Siamese network with contrastive learning and multi-task optimization. The architecture simultaneously performs abnormality detection and anatomical region localization using shared-weight CNN backbones and dynamic pair sampling to address class imbalance.

Clinical Integration: Fuse imaging data with 22 clinical features from fetal metrics (baseline heart rate, accelerations, uterine contractions) and 6 maternal health risk factors (blood pressure, glucose, BMI) using ensemble models (Random Forest, XGBoost) with SHAP-based interpretability.

Model Deployment Optimization: Apply INT8 post-training quantization to reduce model size to <10 MB, enabling edge deployment in resource-limited clinical settings while maintaining 98.6% classification accuracy and reducing manual screening time by 60-70% [20].

Experimental Workflow: Fetal Health Assessment

Research Reagent Solutions for Experimental Implementation

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Cheminformatics toolkit for molecular similarity calculation | Generates Tanimoto similarity scores using ECFP4 fingerprints [22] |

| SMOTE | Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique for data imbalance | Balances class ratios in fetal (22 features) and maternal (6 risk factors) health datasets [20] |

| ECFP4 Fingerprints | Extended-Connectivity Fingerprints for molecular representation | Captures circular atom environments for Siamese MLP inputs in drug discovery [22] |

| Chemformer | Transformer-based model for SMILES string processing | Processes molecular representations as text strings in Siamese architectures [22] |

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | Model interpretability framework | Explains ensemble model predictions for clinical transparency [20] |

| Stratified K-Fold Cross-Validation | Prevents source leakage in multi-dataset studies | Ensures representative mix of normal/abnormal cases across data sources [20] |

| INT8 Quantization | Model compression technique | Reduces model size to <10MB for edge deployment in clinical settings [20] |

Implementation Considerations and Best Practices

Pairing Strategy Optimization

The efficiency of Siamese network training critically depends on pairing strategies. Similarity-based pairing reduces algorithm complexity from O(n²) to O(n) compared to exhaustive pairing, while maintaining or improving prediction performance [22]. For molecular similarity tasks, Tanimoto similarity calculated using RDKit with ECFP4 fingerprints effectively identifies structurally similar compound pairs. In medical imaging with extreme class imbalance (e.g., 12,400 normal vs. 767 abnormal ultrasound images), curriculum-based pair sampling ensures the model encounters informative pairs during training [20].

Uncertainty Quantification

Siamese networks enable robust uncertainty quantification through variance analysis in predictions from reference compounds [22]. In drug discovery, prediction uncertainty is measured by utilizing variance in predictions from a set of reference compounds, with high prediction accuracy correlating with high confidence. For medical applications, ensemble methods combined with SHAP-based interpretability provide transparent identification of key risk factors while quantifying prediction confidence [20].

Domain Shift Mitigation

When training on heterogeneous data sources (e.g., Zenodo ultrasound images vs. YouTube-sourced abnormal images), implement stratified cross-validation with dataset pooling to prevent model bias toward source-specific features rather than pathological differences [20]. This approach ensures reported performance reflects true generalization capability rather than source leakage, which is particularly crucial for clinical applications where domain shift can significantly impact real-world performance.

Siamese Neural Networks (SNNs) represent a paradigm shift in deep learning, moving from traditional classification to a verification-based approach. Their unique architecture, consisting of two or more identical subnetworks that share weights, enables them to learn similarity metrics between inputs rather than direct classification labels. This capability makes SNNs particularly advantageous in real-world scenarios where data is limited or where systems must recognize classes never seen during training—conditions that typically challenge conventional models. This document outlines the quantitative benefits and provides detailed protocols for applying SNamese Networks in authorship research and drug development, addressing the critical challenges of open-set recognition and few-shot learning.

Quantitative Performance Advantages

The structural advantage of SNNs translates into superior performance in challenging conditions compared to traditional models. The tables below summarize empirical results across various fields.

Table 1: Performance in Open-Set and Verification Tasks

| Application Domain | Model / Approach | Performance | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Image Attribution [23] | Siamese-based Verification Framework | High accuracy in closed and open-set settings | Generalizes to verify images from unknown generative architectures |

| MIMO Recognition in OWC [24] | Siamese Neural Network (SNN) | >90% accuracy | High accuracy with only 9 fixed sampling points for training |

| Speech Deepfake Tracing (Open-Set) [25] | Zero-shot Cosine Scoring (SNN-inspired) | Equal Error Rate (EER): 21.70% | Outperforms few-shot methods (EER: 22.65%-27.40%) in open-set trials |

| Speech Deepfake Tracing (Closed-Set) [25] | Few-shot Siamese Backend | Equal Error Rate (EER): 15.11% | Outperforms zero-shot cosine scoring (EER: 27.14%) |

Table 2: Performance in Limited Data and Specific Domains

| Application Domain | Model / Approach | Performance | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fetal Health Assessment [20] | SNN with Few-Shot Learning | 98.6% classification accuracy | Effective with only 767 anomalous training samples |

| Targeted Advertising [16] | Siamese Network for User Embeddings | F1: 0.75, ROC-AUC: 0.79 | Outperforms baselines by 41.61% without explicit feature engineering |

| Authorship Verification [19] | Siamese Network (RoBERTa + Style features) | Competitive results on imbalanced, diverse data | Robust performance under real-world conditions |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Authorship Verification with Style and Semantic Features

This protocol is designed to determine if two texts are from the same author, a common open-set problem in digital forensics and plagiarism detection [19].

- Objective: To verify whether two given text samples, (TextA) and (TextB), were authored by the same individual.

- Key Materials:

- Textual Data: A collection of documents from multiple authors.

- Pre-trained Language Model: RoBERTa, for generating semantic embeddings.

- Style Feature Extractor: A predefined set of features including sentence length, word frequency, and punctuation counts.

- Procedure:

- Feature Extraction:

- Process both (TextA) and (TextB) through RoBERTa to obtain dense semantic embedding vectors.

- Compute a set of stylistic features for each text.

- Feature Fusion:

- Combine the semantic embeddings and stylistic features into a unified representation for each text. The study proposes architectures like Feature Interaction or simple Concatenation for this step [19].

- Similarity Learning:

- Feed the fused representations of the text pair into the twin networks of the Siamese architecture.

- The network is trained using a contrastive or triplet loss function, which teaches the model to map texts by the same author closer in the latent space and push apart those by different authors.

- Verification:

- During inference, the similarity score between the two text representations is computed.

- A threshold is applied to this score to accept or reject the hypothesis that the texts share an author.

- Feature Extraction:

- Considerations: This approach consistently outperforms models using semantic features alone, proving the value of explicit stylistic markers for author discrimination [19].

Protocol 2: Few-Shot Molecular Property Prediction

This protocol addresses data scarcity in drug discovery by predicting properties of new compounds using very few examples [22].

- Objective: To predict the property of a query compound using a limited number of reference compounds with known properties.

- Key Materials:

- Chemical Dataset: A set of compounds with measured properties (e.g., solubility, binding affinity).

- Molecular Representation: Extended-Connectivity Fingerprints (ECFP4) or SMILES strings processed by a transformer (Chemformer) [22].

- Procedure:

- Similarity-Based Pairing:

- For each compound in the training set, pair it with its most similar compound based on Tanimoto similarity using ECFP4 fingerprints. This reduces the number of training pairs from O((n^2)) to O((n)), avoiding combinatorial explosion [22].

- Model Training (Delta Model):

- The Siamese Network is trained on these pairs. The two subnetworks each take a molecule's representation.

- The network is trained to predict the difference (delta) in the target property between the two compounds in a pair.

- Inference:

- For a new query compound, its property is inferred by comparing it to one or more reference compounds with known properties.

- The network predicts the delta between the query and reference, which is then added to the reference's known value to obtain the absolute property for the query.

- Similarity-Based Pairing:

- Advantages: This method efficiently leverages small datasets and can also provide uncertainty estimates by assessing the variance in predictions from multiple reference compounds [22].

Architecture and Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the core Siamese Network architecture and its application in an authorship verification workflow, integrating the protocols described above.

Diagram 1: Siamese Network for Authorship Verification.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item / Technique | Function / Description | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Contrastive / Triplet Loss | A loss function that teaches the network by pulling similar pairs closer and pushing dissimilar pairs apart in the embedding space. | Fundamental to all SNN training for learning a meaningful similarity metric [13]. |

| RoBERTa Embeddings | A pre-trained transformer model that provides high-quality, contextual semantic representations of text. | Capturing the semantic content of texts in authorship verification [19]. |

| Stylometric Features | Quantifiable aspects of writing style (sentence length, punctuation, word frequency). | Providing complementary, author-specific signals alongside semantic features [19]. |

| Extended-Connectivity Fingerprints (ECFP4) | A circular fingerprint that provides a structured vector representation of a molecule's topology. | Representing molecular structure for similarity-based pairing and property prediction [22]. |

| Similarity-Based Pairing | A training pair selection strategy that pairs each sample with its most similar counterpart, reducing complexity from O(n²) to O(n). | Enabling efficient training of SNNs on large chemical datasets [22]. |

| Post-hoc Explanation Methods (e.g., SINEX) | Perturbation-based techniques to interpret which input features contributed most to the SNN's similarity score. | Explaining model decisions in few-shot learning tasks, crucial for building trust [13]. |

Implementing Siamese Networks: Architectural Variations and Feature Engineering Strategies

Application Notes

Graph-based Siamese Networks represent a powerful architecture for tasks involving similarity comparison between text documents. By representing texts as graph structures, this method captures complex, non-sequential relationships between words, moving beyond traditional sequential text processing models. The core innovation involves constructing co-occurrence graphs from text corpora, where nodes represent words or documents, and edges represent their co-occurrence or semantic relationships. A Siamese Neural Network (SNN) with shared weights then processes pairs of these graph representations to compute their similarity in a shared embedding space [16] [26] [27].

This approach is particularly valuable for authorship verification, where the goal is to determine whether two texts are written by the same author. It effectively captures an author's unique stylistic fingerprint by modeling their consistent patterns in word choice and syntactic structure, as reflected in the graph connectivity [28]. The architecture's effectiveness stems from its dual capability: the graph component models the structural features of the text, while the Siamese framework enables robust similarity learning from paired examples.

Experimental results demonstrate the superiority of this approach. In one study, a GCN-SNN model achieved an accuracy of 96.72% and an F1 score of 86.55% on a complex recognition task, significantly outperforming baseline models [26]. Another application in targeted advertising, which utilized autoencoder-based user embeddings within a Siamese network, reported an F1 score of 0.75, a ROC-AUC of 0.79, and a substantial performance lift, outperforming baseline methods by 41.61% on average [16].

Table 1: Performance metrics of Graph-Based Siamese Network models across different applications.

| Application Domain | Model Architecture | Key Metric | Performance Score | Baseline Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dance Movement Recognition [26] | GCN-SNN | Accuracy | 96.72% | Significantly outperformed comparison models |

| F1-Score | 86.55% | |||

| Targeted Advertising [16] | Autoencoder-based SNN | F1-Score | 0.75 | 41.61% average improvement |

| ROC-AUC | 0.79 | |||

| Lift (top 1) | 12.9 | |||

| Authorship Verification [28] | Siamese CNN | Verification Accuracy | ~80% | Achieved with unseen test data |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Text Graph Construction and Model Training for Authorship Verification

I. Objective To create a workflow that transforms a corpus of text documents into co-occurrence graphs and trains a Siamese Network to verify whether two texts share the same authorship.

II. Materials and Reagents Table 2: Essential research reagents and computational tools for graph-based text analysis.

| Item Name | Function / Purpose | Specifications / Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Text Corpus | Raw data for model training and evaluation | IAM Database [28], custom architectural text datasets [27] |

| Graph Construction Library | Converts text into graph structures (nodes, edges) | NetworkX, PyTorch Geometric |

| Deep Learning Framework | Implements and trains neural network models | PyTorch, TensorFlow |

| Pre-trained Language Model | Generates initial word/document embeddings | BERT, RoBERTa [27] |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) | Extracts features from graph-structured data | Graph Convolutional Network (GCN), Graph Attention Network (GAT) [27] |

| Siamese Network Architecture | Compares two inputs for similarity measurement | Twin networks with shared weights [26] [28] |

III. Procedure

Step 1: Data Preprocessing and Graph Construction

- Text Cleaning: For each document in the corpus, perform lowercasing, remove punctuation, and eliminate stop words.

- Keyword Extraction: Use Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF) to identify the most relevant keywords for each document. This focuses the graph on meaningful terms [27].

- Build Co-occurrence Graph: Construct a heterogeneous graph

G = (V, E)where:V(Nodes): Includes both document nodes and keyword (word) nodes [27].E(Edges): Represent relationships. An edge exists between a document node and a keyword node if the keyword appears in that document. Edges can also connect two word nodes if they co-occur within a defined sliding window (e.g., a fixed number of words) in the corpus [27].

Step 2: Node Representation and Initialization

- Generate initial feature vectors for nodes. For document nodes, use pre-trained models like BERT or RoBERTa to create a contextualized document embedding [27].

- For word nodes, use pre-trained word embeddings (e.g., Word2Vec, GloVe) or embeddings generated from the same BERT/RoBERTa models.

Step 3: Siamese Graph Neural Network Architecture

- Input: A pair of text graphs

(G_i, G_j)corresponding to two documents. - Shared GNN Encoder: Process each graph through an identical (weight-sharing) Graph Neural Network. A Graph Attention Network (GAT) is often preferred as it assigns adaptive weights to neighboring nodes, capturing more nuanced relationships [27].

- Graph-Level Embedding: The GNN generates a node-level embedding for each node in the two graphs. To get a single, graph-level representation for each document, apply a global pooling operation (e.g., mean pooling, attention pooling) that aggregates all node embeddings in the graph [26].

- Similarity Calculation: The final graph-level embeddings for the two input documents,

z_iandz_j, are compared using a distance metricDin the latent space. Standard metrics include Cosine Similarity or Euclidean Distance [16] [26].Similarity = 1 - D(z_i, z_j)

Step 4: Model Training and Loss Function

- Prepare Training Pairs: Create pairs of input graphs with labels:

Y=1if the two documents have the same author,Y=0otherwise. - Contrastive Loss: Train the network using a contrastive loss function. This loss function minimizes the distance between embeddings of same-author pairs (

Y=1) while maximizing the distance for different-author pairs (Y=0), effectively teaching the network to pull similar examples closer and push dissimilar examples apart in the embedding space [29] [28].

Graph-Based Siamese Network Workflow for Authorship Verification

Protocol: Ablation Study for Model Component Validation

I. Objective To quantitatively evaluate the contribution of each major component in the Graph-Based Siamese Network pipeline.

II. Procedure

- Baseline Establishment: Train and evaluate a baseline model that uses a simple text representation (e.g., TF-IDF vectors) with a standard Siamese network, excluding graph components.

- Component Evaluation: Train and evaluate several ablated versions of the full model:

- Ablation 1 (GCN vs. GAT): Replace the Graph Attention Network (GAT) encoder with a standard Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) that treats all neighboring nodes equally, without attention [27].

- Ablation 2 (Embedding Source): Replace the pre-trained BERT/RoBERTa initial embeddings with simpler, static word embeddings (e.g., Word2Vec) to isolate the benefit of contextualized representations [27].

- Ablation 3 (Graph Structure): Remove the graph structure entirely and use a Siamese network on sequential text representations (e.g., BiLSTM) to validate the importance of the graph-based approach.

- Metric Tracking: Compare the performance (Accuracy, F1-Score) of all ablated models against the full model on a held-out test set. The performance drop in an ablated model highlights the importance of the removed component.

Siamese GNN Architecture for Text Comparison

Authorship verification, the task of determining whether two texts were written by the same author, is a crucial challenge in natural language processing with significant applications in security, forensics, and academic integrity. The BiBERT-AV framework represents a significant advancement in this domain by leveraging a Siamese network architecture integrated with pre-trained BERT and Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (Bi-LSTM) layers. This hybrid model synergizes BERT's deep contextual understanding with Bi-LSTM's capacity for capturing sequential dependencies, creating a powerful tool for analyzing authorial style [30].

Within the broader context of Siamese networks for authorship research, BiBERT-AV offers a sophisticated approach that moves beyond traditional methods reliant on manual feature engineering. By employing a Siamese structure, the model learns to directly compare textual representations, focusing on the distinctive writing style of authors rather than topic-specific content. This architecture has demonstrated robust performance even when applied to larger author sets, maintaining accuracy where simpler models deteriorate [30].

Architecture and Mechanism of Action

The BiBERT-AV architecture employs a Siamese network framework with twin branches, each processing one of the two texts being compared for authorship. Each branch consists of a pre-trained BERT model for generating contextualized embeddings, followed by a Bi-LSTM layer that captures sequential patterns in the embedding space. The outputs from both branches are then compared using a distance metric to determine authorship similarity [30].

Core Architectural Components

Pre-trained BERT Encoder: The model utilizes BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) to generate context-aware embeddings for each token in the input text. Unlike static word embeddings, BERT embeddings dynamically adjust based on surrounding context, capturing nuanced semantic information crucial for identifying writing style patterns. The transformer architecture's self-attention mechanism enables the model to weigh the importance of different words in relation to each other, effectively capturing an author's characteristic syntactic structures and lexical choices [31] [30].

Bi-LSTM Sequence Modeling: The embeddings generated by BERT are subsequently processed by a Bi-LSTM layer, which analyzes the sequential progression of embeddings in both forward and backward directions. This bidirectional analysis captures long-range dependencies and stylistic patterns that manifest across sentence structures, such as an author's tendency toward specific syntactic constructions or paragraph organization. The Bi-LSTM effectively models the temporal dynamics of writing style that may be obscured in bag-of-words or static embedding approaches [31].

Siamese Comparison Mechanism: The Siamese architecture enables direct comparison between the processed representations of two texts. The model computes a similarity score between the feature vectors extracted from each text branch, typically using distance metrics like cosine similarity or Euclidean distance. This approach allows the model to learn distinctive features that differentiate authors without requiring explicit feature engineering [30] [19].

Signaling Pathway and Information Flow

The following diagram illustrates the architectural workflow and signaling pathway of the BiBERT-AV model:

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Dataset Preparation and Preprocessing

The evaluation of BiBERT-AV utilizes fanfiction texts from the PAN@CLEF 2021 shared task, which provides a challenging testbed for authorship verification in cross-topic and open-set scenarios. The dataset includes both "small" and "large" corpus settings to evaluate model performance under different data conditions [10].

Text Cleaning and Normalization:

- Remove metadata, headers, and non-textual elements from documents

- Normalize Unicode characters and standardize whitespace usage

- Implement sentence segmentation while preserving punctuation patterns

- Optionally perform tokenization and lowercasing based on experimental configuration

Data Partitioning Strategy:

- Split data into training, validation, and test sets maintaining author disjointness

- Ensure balanced representation of positive and negative pairs in training

- Implement cross-topic evaluation where texts from the same author cover different subjects

Model Training Protocol

Hyperparameter Configuration:

| Parameter | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| BERT Model | BERT-Base | 12 layers, 768 hidden dimensions, 12 attention heads |

| Bi-LSTM Layers | 1-2 | 128-256 hidden units per direction |

| Learning Rate | 2e-5 | AdamW optimizer with linear warmup |

| Batch Size | 16-32 | Adjusted based on available memory |

| Sequence Length | 256-512 tokens | Truncation or padding applied |

| Dropout Rate | 0.1-0.3 | Regularization to prevent overfitting |

| Training Epochs | 3-5 | Early stopping based on validation performance |

Training Procedure:

- Initialize BERT weights from pre-trained checkpoints

- Freeze BERT layers for initial epochs, then unfreeze for fine-tuning

- Implement gradient clipping with max norm of 1.0

- Use contrastive loss or binary cross-entropy objective function

- Monitor validation accuracy and loss for model selection

Evaluation Metrics and Benchmarking

The BiBERT-AV model is evaluated using standard authorship verification metrics as established in the PAN@CLEF evaluation framework [10]:

| Metric | BiBERT-AV Performance | Baseline Performance | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| AUC ROC | >90% | 75-85% | Area Under ROC Curve, measures overall discriminative ability |

| F1 Score | >90% | 70-80% | Harmonic mean of precision and recall |

| Brier Score | <0.10 | 0.15-0.25 | Measures probability calibration quality |

| F0.5u | >90% | N/A | PAN-specific metric emphasizing verification accuracy |

| C@1 | >90% | 75-85% | Non-linear combination of accuracy and leave-one-out evaluation |

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details the essential computational tools and resources required for implementing BiBERT-AV:

| Research Reagent | Function/Specification | Application in BiBERT-AV |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-trained BERT Models | BERT-Base (110M parameters) | Provides contextualized word embeddings capturing semantic and syntactic information |

| Bi-LSTM Layer | 128-256 hidden units per direction | Captures sequential dependencies and writing style patterns |

| Siamese Network Framework | Twin architecture with weight sharing | Enables direct comparison of text pairs for authorship verification |

| PAN@CLEF Dataset | Fanfiction texts, cross-topic evaluation | Benchmark dataset for training and evaluation |

| Transformer Library | Hugging Face Transformers | Provides pre-trained BERT models and training utilities |

| Deep Learning Framework | PyTorch or TensorFlow | Model implementation and training infrastructure |

| Text Processing Tools | NLTK, SpaCy | Text preprocessing, tokenization, and feature extraction |

Advanced Experimental Workflow

The complete experimental workflow for BiBERT-AV implementation and evaluation involves multiple stages from data preparation to performance assessment:

Performance Optimization and Technical Considerations

Advanced Training Strategies

Multi-Stage Fine-Tuning:

- Stage 1: Feature extraction with frozen BERT parameters, training only Bi-LSTM and classification layers

- Stage 2: Full model fine-tuning with reduced learning rate for all parameters

- Stage 3: Optional domain adaptation on specific text types or genres

Loss Function Selection:

- Contrastive loss: Directly optimizes distance metric between similar and dissimilar pairs

- Triplet loss: Uses anchor, positive, and negative examples to learn embedding space

- Binary cross-entropy: Traditional classification objective on similarity score

Handling Computational Constraints

The significant computational requirements of BiBERT-AV can be addressed through several optimization strategies:

Memory Efficiency Techniques:

- Gradient accumulation to simulate larger batch sizes

- Mixed-precision training (FP16) to reduce memory footprint

- Dynamic padding and bucketing to minimize padded sequence length

- Gradient checkpointing to trade computation for memory

Inference Optimization:

- Model pruning to remove redundant parameters

- Knowledge distillation to smaller student models

- Quantization to reduced precision for deployment

- ONNX runtime for optimized inference speed

Comparative Analysis with Alternative Architectures

BiBERT-AV demonstrates distinct advantages compared to other authorship verification approaches:

| Architecture | Key Features | Performance | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| BiBERT-AV | BERT + Bi-LSTM + Siamese | AUC: >90% [30] | Computational intensity, requires substantial data |

| Graph-Based Siamese | Graph convolutional networks on POS graphs | AUC: 90-92.83% [10] | Complex graph construction, specialized expertise needed |

| Feature Interaction Networks | RoBERTa + stylistic features | Competitive results on diverse datasets [19] | Manual feature engineering required |

| Traditional Stylometry | Hand-crafted linguistic features | AUC: 75-85% [10] | Limited cross-topic generalization, expertise-dependent |

The BiBERT-AV framework establishes a robust foundation for authorship verification research, particularly through its effective integration of transformer-based contextual understanding with sequential modeling capabilities. Its performance in cross-topic and open-set scenarios demonstrates practical utility for real-world applications where topic variability and unknown authors present significant challenges. Future refinements may focus on computational efficiency, multimodal feature integration, and adaptation to low-resource scenarios.

Feature engineering forms the foundational step in building effective models for stylistic analysis, a domain critical for authorship verification, author profiling, and detecting AI-generated text. Within the context of Siamese networks for authorship research, the selection and implementation of stylistic features directly influence the network's ability to learn discriminative representations of authorship style. Siamese networks, which learn to identify similarity between inputs, require feature sets that robustly capture an author's unique stylistic signature [19] [16]. This document provides detailed application notes and protocols for three core feature categories—Part-of-Speech (POS) Tags, Character N-grams, and Syntactic Patterns—framed within the requirements of a robust authorship verification pipeline using Siamese networks.

Core Feature Classes: Theory and Application

Part-of-Speech (POS) Tags

Theoretical Basis: POS tagging is an automatic text annotation process that assigns syntactic labels (e.g., noun, verb, adjective) to each word, often including morphosyntactic features like gender, tense, and number [32]. The frequency and sequence of these grammatical categories serve as a content-independent style marker, reflecting an author's habitual grammatical choices [33].