Sensitivity Analysis for Likelihood Ratio Models: A Comprehensive Guide for Robust Inference in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive framework for applying sensitivity analysis to likelihood ratio models in biomedical and clinical research.

Sensitivity Analysis for Likelihood Ratio Models: A Comprehensive Guide for Robust Inference in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for applying sensitivity analysis to likelihood ratio models in biomedical and clinical research. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it bridges foundational statistical theory with practical application. The content explores the critical role of sensitivity analysis in quantifying the robustness of model-based inferences to violations of key assumptions, such as unmeasured confounding and missing data mechanisms. It covers methodological implementations, including novel approaches for drug safety signal detection and handling time-to-event data, alongside troubleshooting strategies for common pitfalls like model misspecification and outliers. Finally, the guide presents rigorous validation techniques and comparative analyses to ensure findings are reliable and generalizable, empowering professionals to strengthen the credibility of their statistical conclusions in observational and clinical trial settings.

Core Principles: Understanding Likelihood Ratios and the Imperative for Sensitivity Analysis

Understanding the Core Concept: Likelihood Ratio FAQs

What is a Likelihood Ratio (LR)?

A Likelihood Ratio (LR) is the probability of a specific test result occurring in a patient with the target disorder compared to the probability of that same result occurring in a patient without the target disorder [1]. In simpler terms, it tells you how much more likely a particular test result is in people who have the condition versus those who don't.

How are LRs calculated?

LRs are derived from the sensitivity and specificity of a diagnostic test [2] [1]:

- Positive Likelihood Ratio (LR+) = Sensitivity / (1 - Specificity)

- Negative Likelihood Ratio (LR-) = (1 - Sensitivity) / Specificity

Why are LRs more useful than sensitivity and specificity alone?

Unlike predictive values, LRs are not impacted by disease prevalence [2] [1]. This makes them particularly valuable for:

- Applying test characteristics across different patient populations

- Combining results from multiple diagnostic tests

- Calculating precise post-test probabilities for target disorders

How do I interpret LR values?

The power of an LR lies in its ability to transform your pre-test suspicion into a post-test probability [1]:

| LR Value | Interpretation | Effect on Post-Test Probability |

|---|---|---|

| > 10 | Large increase | Very useful for "ruling in" disease |

| 5-10 | Moderate increase | |

| 2-5 | Small increase | |

| 0.5-2 | Minimal change | Test rarely useful |

| 0.2-0.5 | Small decrease | |

| 0.1-0.2 | Moderate decrease | |

| < 0.1 | Large decrease | Very useful for "ruling out" disease |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Diagnostic Test Validation Protocol

Objective: To determine the sensitivity, specificity, and likelihood ratios of a new diagnostic assay for clinical use.

Materials & Methods:

Patient Cohort Selection: Recruit a representative sample of the target population, ensuring spectrum of disease severity is included.

Reference Standard Application: All participants undergo the "gold standard" diagnostic test to establish true disease status.

Index Test Administration: The new diagnostic test is administered blinded to reference standard results.

Data Collection: Results are recorded in a 2x2 contingency table:

| Disease Present | Disease Absent | |

|---|---|---|

| Test Positive | True Positive (a) | False Positive (b) |

| Test Negative | False Negative (c) | True Negative (d) |

- Statistical Analysis:

- Sensitivity = a/(a+c)

- Specificity = d/(b+d)

- LR+ = Sensitivity/(1-Specificity)

- LR- = (1-Sensitivity)/Specificity

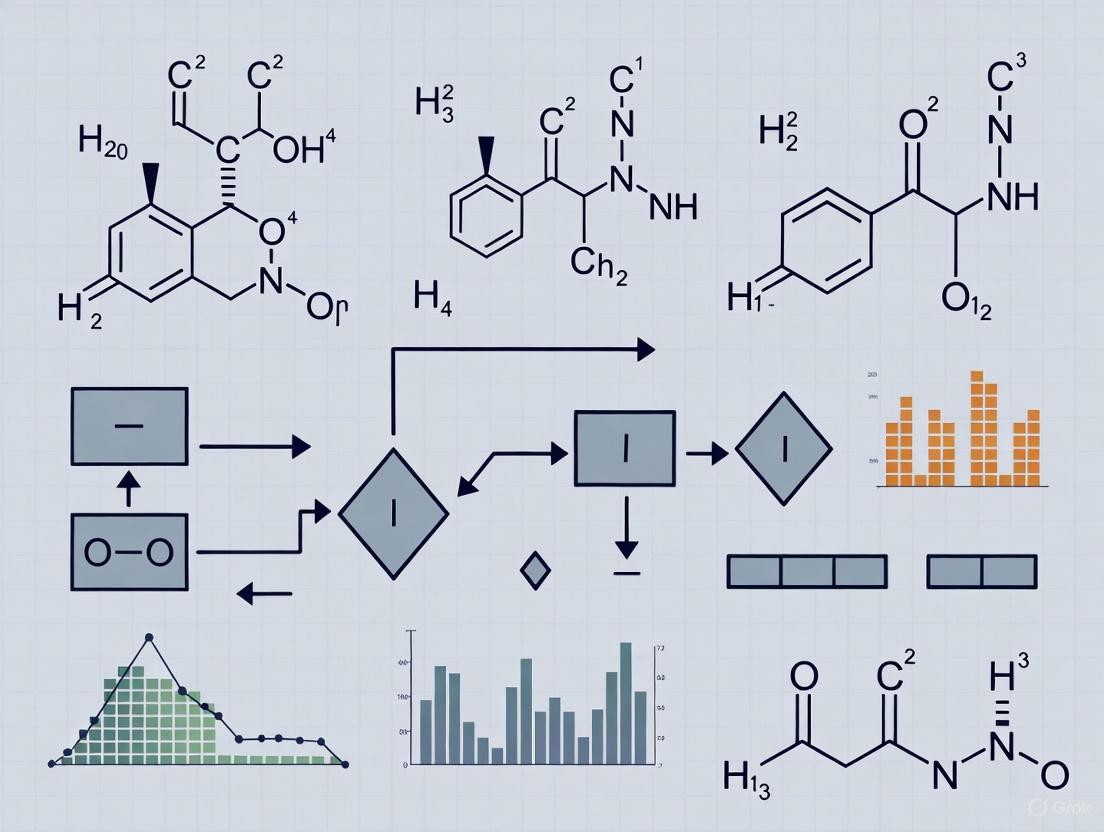

Workflow Visualization:

Application Example: Serum Ferritin for Iron Deficiency

Based on published research [1]:

- Sensitivity: 90% (731/809)

- Specificity: 85% (1500/1770)

- LR+: 6 (90/15)

- LR-: 0.12 (10/85)

Probability Calculation Workflow:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software (R, Python, SAS) | Calculate LRs, confidence intervals, and precision estimates | Data analysis from diagnostic studies |

| Reference Standard Materials | Establish true disease status for validation studies | Gold standard comparator development |

| Sample Size Calculators | Determine adequate participant numbers for target precision | Study design and power calculations |

| Color Contrast Tools | Ensure accessibility of data visualizations | Creating compliant charts and graphs [3] [4] |

| Material Design Color Palette | Pre-designed accessible color schemes | Data visualization and UI design [5] [6] |

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Problem: Inconsistent LR values across studies

Solution: Consider spectrum bias. Ensure your validation population matches the intended use population. LRs can vary with disease severity and patient characteristics.

Problem: Difficulty communicating LR results to clinicians

Solution: Use visual aids like probability nomograms and consider alternative presentation formats. Research indicates that the optimal way to present LRs to maximize understandability is still undetermined and may require testing different formats with your audience [7].

Problem: Low precision in LR estimates

Solution: Increase sample size. Use confidence intervals to communicate uncertainty. Consider bootstrap methods for interval estimation.

Problem: Integrating multiple test results

Solution: Multiply sequential LRs. If Test A has LR+ = 4 and Test B has LR+ = 5, the combined LR+ = 4 × 5 = 20.

Advanced Applications: Complex Model Comparison

In sensitivity analysis and model comparison, LRs extend beyond diagnostic testing:

Model Selection Protocol:

- Fit competing models to the same dataset

- Calculate likelihoods for each model

- Compute LR = Likelihood(Model A)/Likelihood(Model B)

- Apply decision thresholds based on LR values

- Interpret using similar guidelines as diagnostic LRs

Visualization of Model Comparison:

FAQs: Core Concepts and Common Problems

Q1: What is the fundamental purpose of a sensitivity analysis in statistical inference?

A sensitivity analysis is a method to determine the robustness of an assessment by examining the extent to which results are affected by changes in methods, models, values of unmeasured variables, or assumptions. It addresses "what-if-the-key-inputs-or-assumptions-changed"-type questions, helping to identify which results are most dependent on questionable or unsupported assumptions. When findings are consistent after these tests, the conclusions are considered "robust" [8].

Q2: In the context of likelihood ratio models, my results are sensitive to model specification. How can I troubleshoot this?

This is a common issue when modeling complex relationships. A primary step is to assess the impact of alternative statistical models.

- Action: Conduct a sensitivity analysis by changing the analysis models or modifying the functional form. For instance, if using a linear model, consider if a generalized linear model is more appropriate. Compare the results from these different models against your primary analysis.

- Goal: Identify if your key conclusions (e.g., statistical significance of a treatment effect) change under different plausible modeling approaches. A lack of change strengthens the credibility of your findings [9] [8].

Q3: My likelihood ratio test for a meta-analysis has low power. What are potential causes and solutions?

Low power in this context can stem from the model's complexity and the estimation method used.

- Cause: The increased complexity of models like location-scale meta-analysis models can make fitting challenging and impact the performance of statistical tests.

- Solution: A simulation study found that using Restricted Maximum Likelihood (REML) estimation can yield better statistical properties, such as Type I error rates closer to the nominal level. Furthermore, the Likelihood-Ratio Test (LRT) itself was shown to achieve the highest statistical power compared to Wald-type or permutation tests, making it a good choice for detecting true effects [10].

Q4: How do I quantify the robustness of a causal inference from an observational study?

For causal claims, specialized sensitivity analysis techniques are required to quantify how strong an unmeasured confounder would need to be to alter the inference.

- Technique 1: Robustness of Inference to Replacement (RIR): This method answers: "To invalidate the inference, what percentage of the data would have to be replaced with counterfactual cases for which the treatment had no effect?" [11]

- Technique 2: Impact Threshold for a Confounding Variable (ITCV): This technique answers: "An omitted variable would have to be correlated at _ with the predictor of interest and with the outcome to change the inference." [11]

- Tool: These analyses can be conducted in R using the

pkonfoundcommand or via the online appkonfound-it[11].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Handling Protocol Deviations and Non-Compliance in Clinical Trials

Problem: Participants in a randomized controlled trial (RCT) do not adhere to the prescribed intervention, potentially diluting the observed treatment effect and biasing the results.

Solution Steps:

- Primary Analysis: First, perform an Intention-to-Treat (ITT) analysis, where participants are analyzed according to the group to which they were originally randomized, regardless of what treatment they actually received. This is the standard primary analysis for RCTs.

- Sensitivity Analyses: Perform the following sensitivity analyses to test the robustness of your ITT conclusion:

- Per-Protocol (PP) Analysis: Exclude participants who majorly violated the study protocol from the analysis. This estimates the effect under ideal conditions.

- As-Treated (AT) Analysis: Analyze participants based on the treatment they actually received, rather than the one they were assigned to.

- Interpretation: Compare the results of the ITT, PP, and AT analyses. If all three lead to the same qualitative conclusion (e.g., the intervention is effective), your result is considered robust. If they differ, you must discuss the potential reasons and implications in your report [8].

Guide 2: Assessing Robustness to Unmeasured Confounding

Problem: In an observational study assessing a new drug's effect, a critic argues that your finding could be explained by an unmeasured variable (e.g., socioeconomic status).

Solution Steps:

- Calculate the E-value: The E-value quantifies the minimum strength of association that an unmeasured confounder would need to have with both the treatment and the outcome to fully explain away the observed effect. It can be calculated for both the effect estimate and the confidence interval limits.

- Benchmarking: Compare the E-value to the strengths of association of measured confounders in your model. If the E-value is much larger than the associations you have already accounted for, it suggests that an unmeasured confounder would need to be unrealistically strong to negate your result.

- Reporting: Clearly report the E-value alongside your main results. For example: "The hazard ratio for the drug's effect was 0.62 (95% CI: 0.48, 0.79). The E-value was 2.84, indicating that an unmeasured confounder would need to be associated with both treatment and outcome by risk ratios of 2.84-fold each to explain away the effect, which is stronger than any measured confounder in our study" [9].

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Simulation Study for Evaluating a New Likelihood Ratio Test

This protocol is adapted from studies that evaluate statistical tests through Monte Carlo simulation [10] [12].

Objective: To compare the performance (Type I error rate and statistical power) of a proposed Empirical Likelihood Ratio Test (ELRT) against a standard test (e.g., Ljung-Box test) for identifying an AR(1) time series model.

Methodology:

- Data Generation: Generate multiple (e.g., 10,000) synthetic time series datasets under two scenarios:

- Null Hypothesis (H₀): Data are generated from a true AR(1) model to assess Type I error rate.

- Alternative Hypothesis (H₁): Data are generated from a different model (e.g., AR(2)) to assess statistical power.

- Model Application: On each generated dataset, apply both the proposed ELRT and the standard Ljung-Box test.

- Performance Calculation:

- Empirical Type I Error: Calculate the proportion of times the tests incorrectly reject H₀ when H₀ is true. This should be close to the chosen significance level (e.g., 5%).

- Empirical Power: Calculate the proportion of times the tests correctly reject H₀ when H₁ is true.

Expected Workflow:

Protocol 2: Sensitivity Analysis for Observational Study on Drug Effects

This protocol is based on reviews of best practices in studies using routinely collected healthcare data [9].

Objective: To assess the robustness of a primary analysis estimating a drug's treatment effect against potential biases from study definitions and unmeasured confounding.

Methodology:

- Primary Analysis: Conduct the pre-specified main analysis (e.g., a multivariable Cox regression) on the primary outcome.

- Sensitivity Analyses: Plan and execute a series of sensitivity analyses. The table below summarizes the types and examples.

- Comparison and Interpretation: Systematically compare the effect estimates from all sensitivity analyses with the primary analysis. Quantify the difference (e.g., a 24% average difference in effect size was observed in some studies [9]) and discuss the implications of any inconsistencies.

Sensitivity Analysis Framework:

Data Presentation

Table 1: Common Types of Sensitivity Analyses and Their Applications

| Analysis Type | Description | When to Use | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alternative Study Definitions | Using different algorithms or codes to define exposure, outcome, or confounders. | When classifications based on real-world data (e.g., ICD codes) might be misclassified. | In a drug study, varying the grace period for defining treatment discontinuation [9]. |

| Alternative Study Designs | Using a different data source or changing the inclusion criteria for the study population. | To test if findings are specific to a particular population or data collection method. | Comparing results from a primary data analysis to those from a validation cohort [9]. |

| Alternative Modeling | Changing the statistical model, handling of missing data, or testing assumptions. | When model assumptions (e.g., linearity, normality) are in question or to address missing data. | Using multiple imputation instead of complete-case analysis for missing data [9] [8]. |

| Impact of Outliers | Re-running the analysis with and without extreme values. | When the data contain values that are numerically distant from the rest and may unduly influence results. | A cost-effectiveness analysis where excluding outliers changed the cost per QALY ratio [8]. |

| Protocol Deviations | Performing Per-Protocol or As-Treated analyses alongside the primary ITT analysis. | Essential for RCTs where non-compliance or treatment switching is present. | A trial where ITT showed no effect, but a sensitivity analysis on compliers found a significant effect [8]. |

Table 2: Comparison of Tests in a Simulation Study for AR(1) Model Identification

| Test Method | Empirical Size (α=0.05) | Statistical Power | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Empirical Likelihood Ratio Test (ELRT) | Maintains nominal size accurately | Superior power | More reliable for identifying the correct AR(1) model structure compared to the Ljung-Box test [12]. |

| Ljung-Box (LB) Test | Less accurate empirical size | Lower power | As an omnibus test, it can be less powerful for specifically detecting departures from an AR(1) model [12]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Software and Packages

- R and

pkonfound: For conducting sensitivity analyses for causal inference using RIR and ITCV methods [11]. - R and

metafor: A key package for fitting location-scale meta-analysis models and performing likelihood ratio tests, supporting both ML and REML estimation [10]. konfound-itWeb App: A user-friendly, code-free interface for running sensitivity analyses for causal inferences. Accessible at http://konfound-it.com [11].

Methodological Frameworks

- Robustness of Inference to Replacement (RIR): A framework to quantify how many cases would need to be replaced with non-responsive cases to change a statistical inference [11].

- Impact Threshold for a Confounding Variable (ITCV): A framework to quantify how strong an unmeasured confounder would need to be to change an inference [11].

- E-value: A single number that summarizes the minimum strength of association an unmeasured confounder would need to have to explain away a treatment-outcome association [9].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Unmeasured Confounding in Observational Studies

Problem: A researcher is concerned that an observed causal effect between a new drug and patient recovery might be biased due to an unmeasured confounder, such as socioeconomic status.

Diagnosis: The E-value is a quantitative measure that can assess how strong an unmeasured confounder would need to be to explain away the observed treatment effect [13]. A small E-value suggests your results are robust to plausible confounding, while a large E-value indicates fragility.

Solution:

- Calculate the E-value for your point estimate and confidence intervals [13].

- Interpret the E-value in the context of your field's knowledge. Could a confounder of this strength reasonably exist?

- Report the E-value alongside your causal effect estimate to transparently communicate robustness.

Guide 2: Handling Noncompliance in Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs)

Problem: In an RCT, participant noncompliance to the assigned treatment protocol means the treatment received is not randomized, potentially biasing the causal effect of the treatment actually received [14].

Diagnosis: Standard Intention-to-Treat (ITT) analysis gives the effect of treatment assignment, not the causal effect of the treatment itself. When compliance is imperfect, other methods are needed.

Solution: Several estimators can be used when compliance is measured with error [14]:

- Inverse Probability of Compliance Weighted (IPCW) Estimators: Model the probability of compliance given confounders to create a weighted pseudo-population where treatment is independent of confounders [14].

- Regression-Based Estimators: Model the conditional mean of the response given confounders, treatment, and (estimated) compliance status [14].

- Doubly-Robust Augmented Estimators: Combine the IPCW and regression approaches. This estimator is consistent if either the regression model or the model for the probability of compliance is correctly specified, making it more robust to model misspecification [14].

Guide 3: Managing Non-Ignorable Loss to Follow-Up

Problem: Outcome data are missing because participants drop out of a study (Loss to Follow-Up), and the missingness is related to the unobserved outcome itself. This is known as Missing Not at Random (MNAR) data, which can severely bias causal effect estimates [15].

Diagnosis: Standard imputation methods assume data are Missing at Random (MAR). When this assumption is violated, sensitivity analysis is required.

Solution: Implement a multiple-imputation-based pattern-mixture model [15]:

- Define one or more plausible MNAR mechanisms (e.g., participants with worse outcomes are more likely to drop out).

- Impute the missing data multiple times under each specified MNAR mechanism.

- Analyze the completed datasets and pool the results.

- Compare the causal effect estimates across the different MNAR scenarios to test the robustness of your original conclusion [15].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What does a "robust" finding actually mean in causal inference? A robust finding is one that does not change substantially when key assumptions are tested or violated. This includes being insensitive to plausible unmeasured confounding, different model specifications, or non-ignorable missing data mechanisms [13] [14] [15]. Robustness does not prove causality, but it significantly increases confidence in the causal conclusion.

Q2: My analysis found a significant effect, but the E-value is low. What should I do? A low E-value indicates that a relatively weak unmeasured confounder could negate your observed effect. You should [13]:

- Acknowledge this limitation transparently in your reporting.

- Use prior knowledge to argue whether a confounder of such strength is likely.

- Consider designing a follow-up study that directly measures and adjusts for the suspected confounder.

Q3: What is the practical difference between "doubly-robust" estimators and other methods? Doubly-robust estimators provide two chances for a correct inference. They will yield a consistent causal estimate if either your model for the treatment (or compliance) mechanism or your model for the outcome is correctly specified [14]. This is a significant advantage over methods that require a single model to be perfectly specified, which is often an unrealistic assumption in practice.

Q4: How do I choose which sensitivity analysis to use? The choice depends on your primary threat to validity:

- For unmeasured confounding in observational studies, use the E-value or Rosenbaum bounds [13].

- For noncompliance in RCTs, use IPCW, regression, or doubly-robust estimators [14].

- For non-ignorable missing outcome data, use pattern-mixture models or other MNAR sensitivity analyses [15].

Quantitative Data Tables

Table 1: Comparison of Sensitivity Analysis Methods for Causal Inference

| Method | Primary Use Case | Key Inputs | Interpretation of Result | Key Assumptions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E-value [13] | Unmeasured confounding | Risk Ratio, Odds Ratio | Strength of confounder needed to explain away the effect | Confounder must be associated with both treatment and outcome. |

| Rosenbaum Bounds [13] | Unmeasured confounding in matched studies | Sensitivity parameter (Γ) | Range of p-values or effect sizes under varying confounding | Specifies the degree of hidden bias. |

| Doubly-Robust Estimators [14] | Noncompliance, general model misspecification | Treatment and outcome models | Causal effect estimate | Consistent if either the treatment or outcome model is correct. |

| Tipping Point Analysis [13] | Unmeasured confounding | Effect estimate, confounder parameters | The confounder strength that changes study conclusions | Pre-specified assumptions about confounder prevalence. |

Table 2: Scenario Analysis for Non-Ignorable Loss to Follow-Up

| MNAR Scenario | Imputation Model Adjustment | Impact on Causal Risk Ratio (Example) | Robustness Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Base Case (MAR) | None | 0.75 (0.60, 0.95) | Reference |

| Scenario 1: Mild MNAR | Dropouts 20% more likely to have event | 0.78 (0.62, 0.98) | Robust (Conclusion unchanged) |

| Scenario 2: Severe MNAR | Dropouts 50% more likely to have event | 0.85 (0.68, 1.06) | Not Robust (CI includes null) |

| Scenario 3: Protective MNAR | Dropouts 20% less likely to have event | 0.73 (0.58, 0.92) | Robust (Conclusion unchanged) |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing a Sensitivity Analysis for Unmeasured Confounding using the E-value

Objective: To quantify the robustness of a causal risk ratio (RR) to potential unmeasured confounding.

Materials: Your dataset, statistical software (e.g., R, Stata).

Procedure:

- Estimate the Causal Effect: Fit your primary model to obtain the adjusted Risk Ratio (RR) and its confidence interval (CI).

- Calculate the E-value: Compute the E-value for the point estimate and the CI limit closest to the null.

- The E-value for an RR is calculated as:

E-value = RR + sqrt(RR * (RR - 1))for RR > 1. For RR < 1, first take the inverse of the RR (1/RR).

- The E-value for an RR is calculated as:

- Interpret the Result: The E-value represents the minimum strength of association that an unmeasured confounder would need to have with both the treatment and the outcome, on the risk ratio scale, to fully explain away the observed association [13].

- Report: Present the E-values alongside your primary result to communicate its sensitivity.

Protocol 2: Applying a Doubly-Robust Estimator for Noncompliance in an RCT

Objective: To estimate the causal effect of treatment received in the presence of noncompliance, with robustness to model misspecification.

Materials: RCT data including: randomized treatment assignment (A), treatment actually received (Z), outcome (Y), and baseline covariates (X).

Procedure:

- Specify Models:

- Treatment/Compliance Model: A model (e.g., logistic regression) for the probability of receiving treatment given randomization and covariates,

P(Z|A, X). - Outcome Model: A model (e.g., linear regression) for the expected outcome given randomization, treatment received, and covariates,

E(Y|A, Z, X).

- Treatment/Compliance Model: A model (e.g., logistic regression) for the probability of receiving treatment given randomization and covariates,

- Estimate Parameters: Fit both models to the observed data.

- Construct the Estimator: Implement the augmented inverse probability weighted (AIPW) estimator [14]. This involves: a. Calculating inverse probability weights from the treatment model. b. Using the outcome model to predict counterfactual outcomes under full compliance. c. Combining these components into a single, "augmented" estimator.

- Validate: The estimator is consistent if either the treatment model or the outcome model is correctly specified. Check the sensitivity of your result by varying the specifications of both models [14].

Signaling Pathways & Workflows

Diagram 1: Robustness Assessment Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key Analytical Tools for Robust Causal Inference

| Tool / Method | Function in Analysis | Key Property / Advantage |

|---|---|---|

| E-value [13] | Quantifies the required strength of an unmeasured confounder. | Intuitive and easy-to-communicate metric for sensitivity. |

| Rosenbaum Bounds [13] | Assesses sensitivity of results in matched observational studies. | Does not require specifying the exact nature of the unmeasured confounder. |

| Doubly-Robust Estimator [14] | Estimates causal effects in the presence of noncompliance or selection bias. | Provides two chances for correct inference via dual model specification. |

| Pattern-Mixture Models [15] | Handles missing data that is Missing Not at Random (MNAR). | Allows for explicit specification of different, plausible missing data mechanisms. |

| Inverse Probability Weighting [14] | Corrects for selection bias or confounding by creating a pseudo-population. | Directly addresses bias from missing data or treatment allocation. |

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the primary goal of a sensitivity analysis? Sensitivity analysis determines the robustness of a study's findings by examining how results are affected by changes in methods, models, values of unmeasured variables, or key assumptions. It addresses "what-if" questions to see if conclusions change under different plausible scenarios [16] [8].

My clinical trial has missing data. What is the first step in handling it? The first step is to assess the missing data mechanism. Is it Missing Completely at Random (MCAR), Missing at Random (MAR), or Missing Not at Random (MNAR)? This classification guides the choice of appropriate analytical methods, as MNAR data, in particular, introduce a high risk of bias and require specialized techniques like sensitivity analysis [17].

A reviewer is concerned about unmeasured confounding in our observational study. How can I address this? Sensitivity analysis for unmeasured confounding involves quantifying how strong an unmeasured confounder would need to be to alter the study's conclusions. This can be done by simulating the influence of a hypothetical confounder or using statistical techniques like the Delta-Adjusted approach within multiple imputation to assess the robustness of your results [17] [18].

We had significant protocol deviations in our RCT. Which analysis should be our primary one? The Intention-to-Treat (ITT) analysis, where participants are analyzed according to the group they were originally randomized to, is typically the primary analysis as it preserves the randomization. Sensitivity analyses, such as Per-Protocol (PP) or As-Treated (AT) analyses, should then be conducted to assess the robustness of the ITT findings to these deviations [16] [8].

How do I choose parameters for a sensitivity analysis? The choice should be justified based on theory, prior evidence, or expert opinion. It is crucial to vary parameters over realistic and meaningful ranges. For multiple parameters, consider their potential correlations and use methods like multivariate sensitivity analysis to account for this interplay [19].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Handling Missing Data in Time-to-Event Analyses

- Problem: Loss to follow-up in a longitudinal study leads to missing time-dependent covariates in a Cox proportional hazards model, potentially biasing survival estimates [17].

- Investigation: Check the proportion and patterns of missing data. If more than 5% of data are missing, simple methods like Complete Case Analysis (CCA) are likely inadequate and can produce biased estimates [17].

- Solution: Implement a structured approach to handle different missing data mechanisms.

- Protocol:

- Specify the Mechanism: Pre-specify in your analysis plan whether you assume data are MAR or NMAR.

- Primary Analysis (MAR): Use Multiple Imputation (MI) to handle missing data under the MAR assumption. Incorporate event-related variables (event indicator, event time) into the imputation model to maintain consistency with the Cox model [17].

- Sensitivity Analysis (NMAR): To assess robustness, use the Delta-Adjusted Multiple Imputation method. This modifies the imputed values by introducing a sensitivity parameter (delta, δ) to reflect plausible departures from the MAR assumption.

- Create multiple versions of the imputed dataset with different delta values.

- Re-run your Cox model on each dataset.

- Compare the range of treatment effect estimates (e.g., hazard ratios) across these scenarios [17].

- Interpretation: If the conclusions from your primary MAR analysis remain consistent across various NMAR scenarios explored with delta-adjustments, your results are considered robust to missing data assumptions [17].

Issue 2: Addressing Protocol Deviations in Randomized Controlled Trials

- Problem: Participants do not adhere to the assigned treatment (non-compliance) or violate the study protocol, potentially diluting the measured treatment effect [8].

- Investigation: Classify the types of deviations (e.g., crossovers, non-adherence, incomplete treatment) and determine which participants are affected.

- Solution: Perform complementary analyses to the primary ITT analysis.

- Protocol:

- Primary Analysis: Conduct an Intention-to-Treat (ITT) analysis. Analyze all participants in the groups they were originally randomized to, regardless of what treatment they actually received.

- Sensitivity Analyses:

- Per-Protocol (PP) Analysis: Restrict the analysis only to participants who complied with the protocol without major violations.

- As-Treated (AT) Analysis: Analyze participants according to the treatment they actually received, regardless of randomization.

- Interpretation: The ITT analysis provides a conservative, "real-world" estimate of effectiveness. If the PP and AT analyses yield results that are consistent in direction and significance with the ITT analysis, confidence in the robustness of the treatment effect is greatly increased [16] [8].

Issue 3: Accounting for Unmeasured Confounding

- Problem: An observational study or external comparator analysis finds an association, but a critic argues that an unmeasured variable could explain the result [18].

- Investigation: Identify potential key confounders that were not collected (e.g., socioeconomic status, genetic factors, disease severity) and hypothesize how they might be related to both the treatment and the outcome.

- Solution: Quantify the potential impact of an unmeasured confounder through simulation or probabilistic bias analysis.

- Protocol: One common approach is to simulate a confounding variable:

- Define Parameters: Make assumptions about the prevalence of the unmeasured confounder in the treatment and control groups and its strength of association with the outcome.

- Adjust the Model: Incorporate this simulated confounder into your statistical model (e.g., a Cox regression or logistic regression) as an additional covariate.

- Iterate: Repeat the analysis across a range of plausible values for the confounder's prevalence and strength.

- Alternative Method: For studies using propensity score weighting, you can simulate how the inclusion of a strong unmeasured confounder would affect the propensity scores and, consequently, the balance between groups and the final estimate [18].

- Interpretation: The analysis shows how much the unmeasured confounder would need to influence the treatment and outcome to change the study's conclusion (e.g., to render a significant result non-significant). This provides a quantitative argument for the robustness of your findings [18].

Table 1: Summary of Sensitivity Analysis Methods for Key Scenarios

| Scenario | Primary Method | Sensitivity Analysis Method(s) | Key Quantitative Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Missing Data | Multiple Imputation (assuming MAR) [17] | Delta-Adjusted Multiple Imputation (for NMAR) [17] | Delta (δ) shift values; Range of hazard ratios/coefficients across imputations |

| Protocol Deviations | Intention-to-Treat (ITT) Analysis [8] | Per-Protocol Analysis; As-Treated Analysis [8] | Comparison of treatment effect estimates (e.g., odds ratio, mean difference) between ITT and sensitivity analyses |

| Unmeasured Confounding | Standard Multivariable Regression | Simulation of Hypothetical Confounder; Probabilistic Bias Analysis [18] | E-value; Strength and prevalence of confounder required to nullify the observed effect |

Detailed Protocol: Delta-Adjusted Multiple Imputation for Missing Data [17]

- Imputation Model Setup: Use a Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations (MICE) framework. Ensure the imputation model includes the event indicator, event/censoring time, and other relevant covariates to preserve the relationship with the time-to-event outcome.

- Baseline Imputation: Generate

mcomplete datasets (e.g., m=20) under the MAR assumption. - Delta-Adjustment: For scenarios exploring NMAR, select a sensitivity parameter

δ. This parameter represents a systematic shift (e.g., adding a fixed value or a multiple of the standard deviation) to the imputed values for missing observations.- For example, if

Y_obsis the mean of the observed data, imputed valuesY_impcould be set toY_obs + δ.

- For example, if

- Analysis: Fit your primary statistical model (e.g., Cox regression) to each of the

mdelta-adjusted datasets. - Pooling: Combine the results from the

manalyses using Rubin's rules to obtain an overall estimate of the treatment effect and its variance for that specificδvalue. - Sensitivity Exploration: Repeat steps 3-5 for a range of plausible

δvalues (both positive and negative) to create a "sensitivity landscape" for your results.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Reagents & Resources for Sensitivity Analysis

| Item | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|

| Statistical Software (R/Stata) | Provides the computational environment and specialized packages (e.g., mice in R, mi in Stata) for implementing multiple imputation and complex modeling [19] [17]. |

| Multiple Imputation Package | Automates the process of creating multiple imputed datasets and pooling results, which is essential for handling missing data under MAR and NMAR assumptions [17]. |

| Sensitivity Parameter (δ) | A user-defined value used in delta-adjustment methods to quantify and test departures from the MAR assumption, allowing researchers to explore NMAR scenarios [17]. |

| Propensity Score Modeling | A technique used in observational studies to adjust for measured confounding by creating a single score that summarizes the probability of receiving treatment given covariates. It forms the basis for weighting (ATE, ATT, ATO) and matching [18]. |

Methodological Workflows

Sensitivity Analysis Decision Workflow

FAQs: Core Concepts and Workflow Design

Q1: What is the fundamental connection between primary analysis and robustness assessment in drug development? A robust primary analysis is the foundation, but it is not sufficient on its own. Robustness assessment, often through sensitivity analysis, is a critical subsequent step that tests how much your primary results change under different, but plausible, assumptions. This is especially important when data may be Missing Not at Random (MNAR), where the fact that data is missing is itself informative. For instance, in a clinical trial, if patients experiencing more severe side effects drop out, their data is MNAR. A primary analysis might assume data is Missing at Random (MAR), but a robustness assessment would test how sensitive the conclusion is to various MNAR scenarios [17].

Q2: How do I structure a workflow to ensure my analytical process is robust? A robust analytical workflow is structured and reproducible. It should include the following key stages [20]:

- Data Acquisition & Extraction: Collect data in standardized formats and create a data dictionary to document each element. Use version control and automate extraction where possible.

- Data Cleaning & Preprocessing: Handle missing values, detect inconsistencies, and encode variables appropriately. Document all steps.

- Modeling & Statistical Analysis: Start with simple models before moving to complex ones. Document all methods, results, and key decisions.

- Validation: Use training, validation, and test datasets. Conduct peer reviews and audits to ensure results are reproducible.

- Reporting & Visualization: Communicate insights clearly with simple visualizations and automated reports to ensure findings are utilized effectively.

Q3: What is a Robust Parameter Design and how is it used? Pioneered by Dr. Genichi Taguchi, Robust Parameter Design (RPD) is an experimental design method used to make a product or process insensitive to "noise factors"—variables that are difficult or expensive to control during normal operation [21] [22]. The goal is to find the optimal settings for the control factors (variables you can control) that minimize the response variation caused by noise factors. For example, a cake manufacturer can control ingredients (control factors) but not a consumer's oven temperature (noise factor). RPD helps find a recipe that produces a good cake across a range of oven temperatures [22].

Q4: What is the Delta-Adjusted Multiple Imputation (DA-MI) approach and when should I use it? DA-MI is a sensitivity analysis technique used when dealing with potentially MNAR data [17]. It starts with a standard Multiple Imputation (which assumes MAR) and then systematically adjusts the imputed values using a sensitivity parameter, delta (δ), to simulate various degrees of departure from the MAR assumption. You should use this method to test the robustness of your results, especially in longitudinal studies where dropouts may be related to the outcome, such as in time-to-event analyses in clinical trials [17].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Inconsistent or non-reproducible results after implementing a Robust Parameter Design.

- Potential Cause: The design may have been improperly fractionated, leading to severe aliasing where the effect of one factor is confused with the effect of another factor or an interaction [22].

- Solution: Verify the design's properties before experimentation. For two-level RPDs, check the generalized resolution and generalized minimum aberration. Designs with higher resolution and lower aberration are preferred as they reduce serious aliasing. Use statistically validated design patterns rather than creating them from scratch without expert knowledge [22].

Problem: Analytical workflow is efficient but results are misleading.

- Potential Cause: Inadequate data cleaning and preprocessing, or "overfitting" where a model is too complex and captures noise instead of the underlying signal [20].

- Solution:

- Reinvest in the data cleaning stage: implement rigorous checks for missing data, inconsistencies, and duplicates.

- For machine learning models, ensure you use a separate training set to build the model, a validation set to tune parameters, and a test set only for the final evaluation to prevent overfitting.

- Benchmark your model's performance against simpler, well-established methods [20].

Problem: Difficulty communicating the uncertainty from a likelihood ratio or sensitivity analysis to non-statistical stakeholders.

- Potential Cause: The format used to present statistical strength (e.g., likelihood ratios) may be difficult for laypersons to comprehend [7].

- Solution: Research indicates that the format of presentation impacts understanding. Move beyond presenting only numerical likelihood ratios. Use a combination of formats:

Experimental Protocols for Robustness Assessment

Protocol 1: Conducting a Sensitivity Analysis using Delta-Adjusted Multiple Imputation

This protocol is for assessing the robustness of a Cox proportional hazards model with missing time-dependent covariate data [17].

1. Primary Analysis (Under MAR):

- Use Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations (MICE) to create

mcomplete datasets (e.g., m=20), assuming the data is Missing at Random. - Fit the Cox model to each of the

mdatasets. - Pool the results using Rubin's rules to get the primary estimate of the treatment effect (e.g., Hazard Ratio).

2. Sensitivity Analysis (Exploring NMAR via Delta-Adjustment):

- Define a set of plausible delta (δ) values. These represent the systematic shift applied to imputed values. For example, δ = { -0.5, -0.2, +0.2, +0.5 }.

- For each value of δ in the set:

- Modify the imputation model used in the MICE procedure by adding the δ value to the imputed values for the missing data.

- Generate a new set of

mimputed datasets under this specific NMAR scenario. - Fit the Cox model to each dataset and pool the results.

- Compare the range of treatment effects (e.g., Hazard Ratios) and their confidence intervals across all δ scenarios to the primary MAR estimate.

3. Interpretation:

- If the conclusion about the treatment effect (e.g., statistical significance or direction of effect) does not change across the range of plausible δ values, the result is considered robust to departures from the MAR assumption.

- If the conclusion changes, this indicates the finding is sensitive to the assumptions about the missing data, and this uncertainty must be reported.

Protocol 2: Executing a Robust Parameter Design Experiment

This protocol outlines the steps to minimize a product's/process's sensitivity to noise factors [21] [22].

1. Problem Formulation with P-Diagram:

- Create a P-Diagram to classify variables.

- Signal (Input): The intended command or setting.

- Response (Output): The desired performance characteristic.

- Control Factors: Parameters you can specify and control.

- Noise Factors: Hard-to-control variables that cause variation.

- Ideal Function: The perfect theoretical relationship between signal and response.

2. Experimental Planning:

- Select an appropriate Orthogonal Array (a highly fractionated factorial design) for the experiment. This array should accommodate your control and noise factors with a minimal number of experimental runs.

- The design is denoted as 2^(m1+m2)-(p1-p2), where m1 is control factors, m2 is noise factors, p1/p2 are fractionation levels [22].

3. Experimentation and Analysis:

- Run the experiment according to the orthogonal array. For each run, expose the system to different combinations of controlled noise factors.

- For each experimental run, calculate the Signal-to-Noise (S/N) Ratio. This metric, derived from Taguchi's Quadratic Loss Function, measures robustness by combining the mean and variance of the response; a higher S/N ratio indicates lower sensitivity to noise [21].

- Use the data to perform two optimization steps:

- Variance Reduction: Identify control factor settings that maximize the S/N ratio.

- Mean Adjustment: Use a "scaling factor" (a control factor that affects the mean but not the S/N ratio) to adjust the mean response to the target value [21].

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

Analytical Robustness Workflow

P-Diagram for Robust Design

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key methodological and informational resources for conducting robust analyses in drug development.

| Tool / Resource Name | Type | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Robust Parameter Design (Taguchi Method) [21] [22] | Statistical Experimental Design | Systematically finds control factor settings to minimize output variation caused by uncontrollable noise factors. |

| Delta-Adjusted Multiple Imputation (DA-MI) [17] | Sensitivity Analysis Method | Tests the robustness of statistical inferences to deviations from the Missing at Random (MAR) assumption in datasets with missing values. |

| P-Diagram [21] | Conceptual Framework Tool | Classifies variables into signal, response, control, and noise factors to succinctly define the scope of a robustness problem. |

| Orthogonal Arrays [21] [22] | Experimental Design Structure | Allows for the efficient and reliable investigation of a large number of experimental factors with a minimal number of test runs. |

| Signal-to-Noise (S/N) Ratio [21] | Robustness Metric | A single metric used in parameter design to predict field quality and find factor settings that minimize sensitivity to noise. |

| FDA Fit-for-Purpose (FFP) Initiative [23] | Regulatory Resource | Provides a pathway for regulatory evaluation and acceptance of specific drug development tools (DDTs), including novel statistical methods, for use in submissions. |

| Drug Development Tools (DDT) Qualification Programs [24] | Regulatory Resource | FDA programs that guide submitters as they develop tools (e.g., biomarkers, clinical outcome assessments) for a specific Context of Use (COU) in drug development. |

Implementation in Practice: Techniques for Applying Sensitivity Analysis to LR Models

What is the Likelihood Ratio Test and what is its primary purpose?

The Likelihood Ratio Test (LRT) is a statistical hypothesis test used to compare the goodness-of-fit between two competing models. Its primary purpose is to determine if a more complex model (with additional parameters) fits a particular dataset significantly better than a simpler, nested model. The simpler model must be a special case of the more complex one, achievable by constraining one or more of the complex model's parameters [25]. The LRT provides an objective criterion for deciding whether the improvement in fit justifies the added complexity of the additional parameters [25].

How does the LRT work? What is the underlying logic?

The underlying logic of the LRT is to compare the maximum likelihood achievable by each model. The test statistic is calculated as the ratio of the maximum likelihood of the simpler model (the null model) to the maximum likelihood of the more complex model (the alternative model) [26]. For convenience, this ratio is transformed into a log-likelihood ratio statistic [27]:

λ_LR = -2 * ln[ L(null model) / L(alternative model) ] = -2 * [ ℓ(null model) - ℓ(alternative model) ]

where ℓ represents the log-likelihood [26]. A large value for this test statistic indicates that the complex model provides a substantially better fit to the data than the simple model. According to Wilk's Theorem, as the sample size approaches infinity, this test statistic follows a chi-square distribution under the null hypothesis [27]. The degrees of freedom for this chi-square distribution are equal to the difference in the number of free parameters between the two models [25].

A Practical Example: Testing a Molecular Clock

The following table summarizes a hypothetical experiment to test whether a DNA sequence evolves at a constant rate (i.e., follows a molecular clock) [25].

| Model Description | Log-Likelihood (ℓ) | Number of Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Null (H₀): HKY85 model with a molecular clock (simpler model) | ℓ₀ = -7573.81 | Fewer parameters (rate homogeneous across branches) |

| Alternative (H₁): HKY85 model without a molecular clock (more complex model) | ℓ₁ = -7568.56 | More parameters (rate varies across branches) |

LRT Calculation and Interpretation:

- Calculate the test statistic: λ_LR = -2 * (ℓ₀ - ℓ₁) = -2 * (-7573.81 - (-7568.56)) = 10.50 [25]

- Determine the degrees of freedom: df = s - 2, where

sis the number of taxa. For a 5-taxon tree, df = 5 - 2 = 3 [25] - Compare to critical value: The critical value for a chi-square distribution with 3 degrees of freedom at a significance level of α=0.05 is 7.82 [25]

- Conclusion: Since our test statistic (10.50) is greater than the critical value (7.82), we reject the null hypothesis. This indicates that the more complex model (without a molecular clock) fits the data significantly better, and the assumption of a homogeneous rate of evolution is not valid for this dataset [25].

Experimental Protocol for Model Comparison

This protocol outlines the key steps for performing a robust Likelihood Ratio Test.

- Define Nested Models: Clearly specify your null (H₀, simpler) and alternative (H₁, more complex) models. Ensure they are hierarchically nested [25].

- Compute Maximum Likelihood: Using your dataset, calculate the maximum likelihood estimates for the parameters of both models. Record the resulting maximum log-likelihood values (ℓ₀ and ℓ₁) [27].

- Calculate Test Statistic: Compute the LRT statistic using the formula: λ_LR = -2 * (ℓ₀ - ℓ₁) [26].

- Determine Degrees of Freedom: Calculate the degrees of freedom (df) as the difference in the number of free parameters between the two models [25].

- Significance Testing: Compare the λLR statistic to the critical value from the chi-square distribution with the calculated df at your chosen significance level (e.g., α = 0.05). If λLR exceeds the critical value, reject the null hypothesis in favor of the more complex model [25].

The logical workflow for this experimental protocol can be visualized as follows:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table lists key conceptual "reagents" and software tools essential for conducting Likelihood Ratio Test analysis.

| Tool/Concept | Function in LRT Analysis |

|---|---|

| Nested Models | A pair of models where the simpler one (H₀) is a special case of the complex one (H₁), created by constraining parameters. This is an imperative requirement for the LRT [25]. |

| Likelihood Function (L(θ)) | The function that expresses the probability of observing the collected data given a set of model parameters (θ). It is the core component from which likelihoods are calculated [28]. |

| Maximized Log-Likelihood (ℓ) | The natural logarithm of the maximum value of the likelihood function achieved after optimizing model parameters. Used directly in the LRT statistic calculation [26]. |

| Chi-Square Distribution (χ²) | The theoretical probability distribution used to determine the statistical significance of the LRT statistic under the null hypothesis, thanks to Wilk's Theorem [27]. |

| Statistical Software (R, etc.) | Platforms used to perform numerical optimization (maximizing likelihoods), compute the LRT statistic, and compare it to the chi-square distribution [27]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

Q1: My LRT statistic is negative. Is this possible, and what does it mean?

A negative LRT statistic typically indicates an error in calculation. The LRT statistic is defined as λ_LR = -2 * (ℓ₀ - ℓ₁), where ℓ₁ is the log-likelihood of the more complex model. Because a model with more parameters will always fit the data at least as well as a simpler one, ℓ₁ should always be greater than or equal to ℓ₀. Therefore, (ℓ₀ - ℓ₁) should be zero or negative, making the full statistic zero or positive. A negative value suggests the log-likelihoods have been swapped in the formula [26].

Q2: Can I use the LRT to compare non-nested models? No, the standard Likelihood Ratio Test is only valid for comparing hierarchically nested models [25]. If your models are not nested (e.g., one uses a normal error distribution and another uses a gamma distribution), the LRT statistic may not follow a chi-square distribution. In such cases, you would need to use generalized methods like relative likelihood or information-theoretic criteria such as AIC (Akaike Information Criterion) for model comparison [26].

Q3: The LRT and the Wald test both seem to test model parameters. What is the difference? The LRT, the Wald test, and the Lagrange Multiplier test are three classical approaches that are asymptotically equivalent but operate differently. The key difference is that the LRT requires fitting both the null and alternative models, while the Wald test only requires fitting the more complex alternative model. The LRT is generally considered more reliable than the Wald test for smaller sample sizes, though it is computationally more intensive because both models must be estimated [26].

Q4: My sample size is relatively small. Should I be concerned about using the LRT? Yes, sample size is an important consideration. Wilk's Theorem, which states that the LRT statistic follows a chi-square distribution, is an asymptotic result. This means it holds as the sample size approaches infinity [27]. With small sample sizes, the actual distribution of the test statistic may not be well-approximated by the chi-square distribution, potentially leading to inaccurate p-values. In such situations, results should be interpreted with caution.

Troubleshooting Guide: Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: What is the primary challenge with unmeasured confounding in indirect treatment comparisons, and when is it most pronounced?

Unmeasured confounding is a major concern in indirect treatment comparisons (ITCs) and external control arm analyses where treatment assignment is non-random. This bias occurs when patient characteristics associated with both treatment selection and outcomes remain unaccounted for in the analysis. The problem is particularly pronounced when comparing therapies with differing mechanisms of action that lead to violation of the proportional hazards (PH) assumption, which is common in oncology immunotherapy studies and other time-to-event analyses. Traditional sensitivity analyses often fail in these scenarios because they rely on the PH assumption, creating an unmet need for more flexible quantitative bias analysis methods. [29] [30]

FAQ 2: My bias analysis results appear unstable with wide confidence intervals. What might be causing this?

This instability often stems from insufficient specification of confounder characteristics or inadequate handling of non-proportional hazards. The multiple imputation approach requires precise specification of the unmeasured confounder's relationship with both treatment and outcome. Ensure you have:

- Clearly defined hypothesized strength of association between confounder and treatment

- Well-specified relationship between confounder and outcome

- Appropriate handling of censoring in time-to-event data

- Sufficient number of imputations (typically 20+)

Additionally, when PH violation is present, using inappropriate effect measures like hazard ratios rather than difference in restricted mean survival time (dRMST) can introduce substantial bias and variability in results. [29] [30]

FAQ 3: How can I determine what strength of unmeasured confounding would nullify my study conclusions?

Implement a tipping point analysis using the following workflow:

- Specify a range of plausible associations between the unmeasured confounder and treatment, and between the confounder and outcome

- Use multiple imputation to create complete datasets adjusting for these specified relationships

- Calculate adjusted treatment effects (preferably dRMST under PH violation) for each scenario

- Identify the confounder strength where confidence intervals cross the null value

- Assess plausibility of identified confounder characteristics in your clinical context

This approach reveals how robust your conclusions are to potential unmeasured confounding and whether plausible unmeasured confounders could explain away your observed effects. [30]

FAQ 4: What are the key differences between delta-adjusted and multiple imputation methods for handling unmeasured confounding?

Table: Comparison of Delta-Adjusted and Multiple Imputation Methods

| Feature | Delta-Adjusted Methods | Multiple Imputation Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Implementation | Bias-formula based direct computation [30] | Simulation-based with Bayesian data augmentation [29] [30] |

| Flexibility | Limited to specific confounding scenarios [30] | High flexibility for various confounding types and distributions [29] [30] |

| PH Violation Handling | Generally requires PH assumption [30] | Valid under proportional hazards violation [29] [30] |

| Effect Measure | Typically hazard ratios [30] | Difference in restricted mean survival time (dRMST) [29] [30] |

| Ease of Use | Relatively straightforward implementation [30] | Requires advanced statistical expertise [30] |

| Output | Direct adjusted effect estimates [30] | Imputed confounder values for weighted analysis [29] [30] |

FAQ 5: How do I validate that my multiple imputation approach for unmeasured confounding is working correctly?

Validation should include both simulation studies and diagnostic checks:

- Perform simulation studies: Generate data with known confounding mechanisms and assess whether your imputation approach accurately recovers the true adjusted effect

- Check convergence: Monitor convergence of your Bayesian data augmentation algorithm

- Assess coverage: Verify that confidence intervals achieve nominal coverage rates

- Compare to full adjustment: When possible, compare results to analyses with all confounders measured

- Conduct sensitivity analyses: Test how results vary under different assumptions about the unmeasured confounder

Research shows that properly implemented imputation-based adjustment can estimate the true adjusted dRMST with minimal bias comparable to analyses with all confounders measured. [29] [30]

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Multiple Imputation with Bayesian Data Augmentation for dRMST

Application: Adjusting for unmeasured confounding in time-to-event analyses with non-proportional hazards.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Define Outcome and Propensity Models:

- Specify outcome model: (f\left({t}{i} | {z}{i}, {x}{i}, {u}{i},{\delta }{i},{\varvec{\theta}},{{\varvec{\beta}}}{x},{{\varvec{\beta}}}_{u}\right))

- Specify propensity model: (\text{logit}\left(p\left({z}{i}=1 | {x}{i}, {u}{i}\right)\right) = {a}{0} + {a}{x}^{T}{x}{i} + {a}{u}{u}{i})

- Where ({t}{i}) represents time-to-event, ({z}{i}) is treatment, ({x}{i}) are measured confounders, and ({u}{i}) is the unmeasured confounder [30]

Specify Confounder Characteristics:

- Define hypothesized prevalence of binary unmeasured confounder

- Specify association between confounder and treatment (({a}_{u}))

- Specify association between confounder and outcome (({{\varvec{\beta}}}_{u}))

Implement Bayesian Data Augmentation:

- Use Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods for multiple imputation

- Iterate between imputing missing confounder values and updating model parameters

- Generate multiple complete datasets (typically 20+ imputations)

Perform Adjusted Analysis:

- Calculate dRMST for each imputed dataset

- Use appropriate weighting schemes for confounder adjustment

- Account for censoring in time-to-event data

Pool Results:

Protocol 2: Tipping Point Analysis for Unmeasured Confounding

Application: Determining the strength of unmeasured confounding required to nullify study conclusions.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Define Parameter Grid:

- Create a systematic grid of plausible values for confounder-treatment association (({a}_{u}))

- Create a systematic grid of plausible values for confounder-outcome association (({{\varvec{\beta}}}_{u}))

- Range should cover clinically realistic scenarios

Iterative Adjustment:

- For each combination of (({a}{u}), ({{\varvec{\beta}}}{u})) in the parameter grid:

- Implement multiple imputation as in Protocol 1

- Calculate adjusted dRMST and confidence intervals

- Store results for each parameter combination

- For each combination of (({a}{u}), ({{\varvec{\beta}}}{u})) in the parameter grid:

Identify Tipping Points:

- Determine the parameter combinations where confidence intervals for dRMST include the null value

- Identify the minimum confounder strength that would nullify findings

- Create contour plots or similar visualizations to display results

Interpret Clinical Relevance:

- Assess whether identified confounder characteristics are plausible in your clinical context

- Determine robustness of study conclusions to potential unmeasured confounding [30]

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Pathways

Multiple Imputation QBA Workflow

Statistical Relationships in Sensitivity Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Methodological Components for Unmeasured Confounding Analysis

| Component | Function | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Bayesian Data Augmentation | Multiple imputation of unmeasured confounders using MCMC methods | Requires specification of prior distributions; computationally intensive but flexible [29] [30] |

| Restricted Mean Survival Time (RMST) | Valid effect measure under non-proportional hazards | Requires pre-specified time horizon; provides interpretable difference in mean survival [29] [30] |

| Tipping Point Analysis Framework | Identifies confounder strength needed to nullify results | Systematically varies confounder associations; produces interpretable sensitivity bounds [30] |

| Propensity Score Integration | Balances measured covariates in observational studies | Can be combined with multiple imputation for comprehensive adjustment [31] |

| Simulation-Based Validation | Assesses operating characteristics of methods | Verifies Type I error control, power, and coverage rates [29] [30] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core advantage of using LRT methods over traditional meta-analysis for drug safety signal detection? Traditional meta-analysis often focuses on combining study-level summary measures (e.g., risk ratio) for a single, pre-specified adverse event (AE). In contrast, the LRT-based methods are designed for the simultaneous screening of many drug-AE combinations across multiple studies, thereby controlling the family-wise type I error and false discovery rates, which is crucial when exploring large safety databases [32] [33] [34].

Q2: How do the LRT methods handle the common issue of heterogeneous data across different studies? The LRT framework offers variations specifically designed to address heterogeneity. The simple pooled LRT method combines data across studies, while the weighted LRT method incorporates total drug exposure information by study, assigning different weights to account for variations in sample size or exposure. Simulation studies have shown these methods maintain performance even with varying heterogeneity across studies [32] [33].

Q3: My data includes studies with different drug exposure times. Is the standard LRT method still appropriate?

The standard LRT method for passive surveillance databases like FAERS uses reporting counts (e.g., n_i.) as a proxy for exposure. However, when actual exposure data (e.g., patient-years, P_i) is available from clinical trials, the model can be adapted to use these exposure-adjusted measures. Using unadjusted incidence percentages when exposure times differ can lead to inaccurate interpretations, and an exposure-adjusted model is more appropriate [33] [35].

Q4: A known problem in meta-analysis is incomplete reporting of adverse events, especially rare ones. Can LRT methods handle this? Standard LRT methods applied to summary-level data may be susceptible to bias from censored or unreported AEs. While the core LRT methods discussed here do not directly address this, recent statistical research has proposed Bayesian approaches to specifically handle meta-analysis of censored AEs. These methods can improve the accuracy of incidence rate estimations when such reporting issues are present [36].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Inconsistent or Missing Drug Exposure Data Across Studies

Issue: The definition and availability of total drug exposure (P_i) may vary or be missing in some studies, making the weighted LRT method difficult to apply.

Solution:

- Imputation with Assumptions: If precise exposure is not collected, it may be imputed using reasonable assumptions based on available data, such as study duration and dosage information [33].

- Standardized Protocols: Ensure future studies adhere to a standardized protocol for collecting and reporting exposure data to ensure consistency [33].

- Sensitivity Analysis: Conduct analyses using both the simple pooled LRT (without exposure data) and the weighted LRT (with imputed data) to assess the robustness of your findings.

Problem: High False Discovery Rate (FDR) When Screening Hundreds of AEs Issue: Simultaneously testing multiple drug-AE combinations increases the chance of false positives. Solution:

- Utilize LRT's Inherent Properties: The LRT method was developed to control the family-wise type I error and FDR. Ensure you are using the maximum likelihood ratio (MLR) test statistic and the correct critical values from the derived distribution [34].

- Confirm with External Evidence: Signals detected by the statistical method should be confirmed by existing medical evidence, biological plausibility, or signals from other independent databases [34].

Problem: Integrating Data from Studies with Different Designs (e.g., RCTs and Observational Studies) Issue: Simple pooling of AE data from studies with different designs can lead to confounding and inaccurate summaries. Solution:

- Stratified Analysis: Use a meta-analytic approach that stratifies by trial or study type to preserve the randomization of RCTs and account for design differences. A valid meta-analysis should feature appropriate adjustments and weights for distinct trials [35].

- Bayesian Hierarchical Models: Consider advanced models that add a layer for the clinical trial level, which can borrow information across studies while accounting for their differences [35].

Key Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Core Protocol: Applying LRT Methods for Signal Detection

The following workflow outlines the standard methodology for applying LRT methods to multiple datasets for safety signal detection [32] [33].

The table below summarizes the three primary LRT approaches for multiple studies, as identified in the literature.

Table 1: Overview of LRT Methods for Drug Safety Signal Detection in Multiple Studies

| Method Name | Description | Key Formula/Statistic | When to Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simple Pooled LRT | Data from multiple studies are pooled together into a single 2x2 table for analysis [32] [33]. | LR_ij = [ (n_ij / E_ij)^n_ij * ( (n_.j - n_ij) / (n_.j - E_ij) )^(n_.j - n_ij) ] / [ (n_.j / n..)^n_.j ] [33] |

Initial screening when study heterogeneity is low and drug exposure data is unavailable or inconsistent. |

| Weighted LRT | Incorporates total drug exposure information (P_i) by study, giving different weights to studies [32] [33]. |

Replaces n_i. with P_i and n.. with P. in the calculation of E_ij and the LR statistic [33]. |

Preferred when reliable drug exposure data (e.g., patient-years) is available and comparable across all studies. |

| Two-Step LRT | Applies the regular LRT to each study individually, then combines the test statistics from different studies for a global test [33]. | Step 1: Calculate LRT statistic per study. Step 2: Combine statistics (e.g., by summing) for a global test [33]. | Useful for preserving study identity and assessing heterogeneity before combining results. |

Applied Example: Protocol for Analyzing PPIs and Osteoporosis

For illustration, one applied study analyzed the effect of concomitant use of Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs) in patients being treated for osteoporosis, using data from 6 studies [32] [33].

Experimental Protocol:

- Data Extraction: For each of the 6 studies, identify patients in two groups: those taking PPI + osteoporosis drug (active group) and those taking placebo + osteoporosis drug (control group).

- Outcome Definition: Identify all reported adverse events of interest from the safety data.

- Contingency Table Construction: For each study and each AE, construct a 2x2 contingency table with the counts for the drug group and the control group.

- Analysis: Apply the chosen LRT method (e.g., weighted LRT if exposure data is available) to the combined data from the 6 studies to test for a global safety signal associated with PPIs.

Table 2: Key Resources for Conducting LRT-based Safety Meta-Analyses

| Category | Item / Method | Function / Description | Key Reference / Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical Methods | Likelihood Ratio Test (LRT) | Core statistical test for identifying disproportionate reporting in 2x2 tables. | [32] [34] |

| Bayesian Hierarchical Model | An alternative/complementary method that accounts for data hierarchy and borrows strength across studies or AE terms. | [35] | |

| Proportional Reporting Ratio (PRR) | A simpler disproportionality method often used for benchmark comparison. | [33] [37] | |

| Data Sources | FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) | A primary spontaneous reporting database for post-market safety surveillance. | [33] [37] [34] |

| EudraVigilance | The European system for managing and analyzing reports of suspected AEs. | [37] | |

| Clinical Trial Databases | Aggregated safety data from multiple pre-market clinical trials for a drug. | [32] [35] | |

| Software & Tools | OpenFDA | Provides interactive, open-source applications for data mining and visualization of FAERS data. | [33] [37] |

| R / SAS | Standard statistical software environments capable of implementing custom LRT and meta-analysis code. | (Implied) |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the most structured method to handle missing data that is suspected to be Not Missing at Random (NMAR) in time-to-event analysis?

The Delta-Adjusted Multiple Imputation (DA-MI) approach is a highly structured method for handling NMAR data in time-to-event analyses. Unlike traditional methods that rely on pattern-mixture or selection models without direct imputation, DA-MI explicitly adjusts imputed values using sensitivity parameters (delta shifts (δ)) within a Multiple Imputation framework [17] [38]. This provides a structured way to handle deviations from the Missing at Random (MAR) assumption. It works by generating multiple datasets with controlled sensitivity adjustments, which preserves the relationship between time-dependent covariates and the event-time outcome while accounting for intra-individual variability [17]. The results offer sensitivity bounds for treatment effects under different missing data scenarios, making them highly interpretable for decision-making [17] [38].

FAQ 2: My primary analysis assumes data is Missing at Random (MAR). How can I test the robustness of my conclusions?

Conducting a sensitivity analysis is essential. Your primary analysis under MAR should be supplemented with sensitivity analyses that explore plausible NMAR scenarios [39]. The Delta-Adjusted method is perfectly suited for this. You would:

- Start with your MAR-based imputation.

- Create multiple versions of your imputed dataset by systematically applying different delta (δ) values to the imputed missing data. These delta values represent specified deviations from the MAR assumption [17] [39].

- Analyze each of these adjusted datasets and combine the results.

- Observe how your estimated treatment effect changes across the different delta values. If your conclusions remain unchanged under a range of plausible NMAR scenarios, your results are considered robust [17].

FAQ 3: What is a "Tipping Point Analysis" for missing data in clinical trials with time-to-event endpoints?

A Tipping Point Analysis is a specific type of sensitivity analysis that aims to find the critical degree of deviation from the primary analysis's missing data assumptions at which the trial's conclusion changes (e.g., from significant to non-significant) [40]. This approach can be broadly categorized into:

- Model-Based Approaches: These involve varying parameters within a statistical model used to handle missing data.

- Model-Free Approaches: These are less emphasized in literature but offer alternative ways to impute missing data and assess robustness [40]. The goal is to evaluate how much the missing data mechanism would need to differ from the MAR assumption to alter the trial's primary outcome, thus providing a practical measure of result reliability [40].

FAQ 4: When should I use a global sensitivity analysis instead of a local one?

You should prefer global sensitivity analysis for any model that cannot be proven linear. Local sensitivity analysis, which varies parameters one-at-a-time around specific reference values, has critical limitations [41]:

- It can be heavily biased for nonlinear models.

- It underestimates the importance of factors that interact.

- It only partially explores the model's parametric space [41]. In contrast, global sensitivity analysis varies all uncertain factors simultaneously across their entire feasible space. This reveals the global effects of each parameter on the model output, including any interactive effects, leading to a more comprehensive understanding of your model's behavior [41].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: My time-to-event analysis has missing time-dependent covariates, and I suspect the missingness is related to a patient's unobserved health status (NMAR).

Solution: Implement a Delta-Adjusted Multiple Imputation (DA-MI) workflow.

| Step | Action | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Specify the MAR Imputation Model | Use Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations (MICE) to impute missing values under the MAR assumption. Ensure the imputation model includes the event indicator, event/censoring time, and other relevant covariates [17] [39]. |

| 2 | Define Delta (δ) Adjustment Scenarios | Choose a range of delta values that represent plausible NMAR mechanisms. For example, a positive δ could increase the imputed value of a covariate for missing cases, assuming that missingness is linked to poorer health [17]. |

| 3 | Generate Adjusted Datasets | Create multiple copies of the imputed dataset, applying the predefined δ adjustments to the imputed values for missing observations [17]. |

| 4 | Analyze and Combine Results | Fit your time-to-event model (e.g., Cox regression) to each adjusted dataset. Pool the results using Rubin's rules to obtain estimates and confidence intervals for each NMAR scenario [17]. |

| 5 | Interpret Sensitivity Bounds | Compare the pooled treatment effects across different δ values. The range of results shows how sensitive your findings are to departures from the MAR assumption [17] [38]. |

Problem: I am unsure which uncertain inputs in my computational model have the most influence on the time-to-event output.

Solution: Perform a global sensitivity analysis for factor prioritization.

| Step | Action | Objective |

|---|---|---|