Raman vs IR Spectroscopy: The Ultimate Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of Raman and Infrared (IR) spectroscopy, two pivotal analytical techniques in biomedical and pharmaceutical sciences.

Raman vs IR Spectroscopy: The Ultimate Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of Raman and Infrared (IR) spectroscopy, two pivotal analytical techniques in biomedical and pharmaceutical sciences. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the fundamental principles, distinct selection rules, and complementary nature of these methods. It delves into their specific applications in cancer diagnostics, liquid biopsy analysis, protein characterization, and quality control, supported by real-world case studies. The guide also addresses practical challenges, such as fluorescence interference in Raman and water absorption in IR, and offers optimization strategies. By synthesizing validation data and emerging trends like AI integration and portable devices, this resource aims to empower scientists in selecting and implementing the optimal spectroscopic technique for their specific research and development goals.

Core Principles Unveiled: Understanding the Fundamental Mechanisms of Raman and IR Spectroscopy

Infrared (IR) and Raman spectroscopy are foundational techniques in molecular analysis that provide complementary insights into chemical structures by probing molecular vibrations through fundamentally different physical interactions with light. While IR spectroscopy relies on the absorption of infrared light by molecular bonds, Raman spectroscopy is based on the inelastic scattering of monochromatic light [1] [2]. These distinct physical mechanisms make each technique uniquely suited for different analytical scenarios while providing vibrational fingerprints crucial for identifying molecular species.

The core distinction lies in their interaction with molecular vibrations: IR spectroscopy measures molecular vibrations that cause a change in the dipole moment of a bond, making it particularly sensitive to polar functional groups. In contrast, Raman spectroscopy detects vibrations that cause a change in molecular polarizability, making it generally more sensitive to non-polar bonds and symmetric molecular vibrations [1] [2]. This complementarity means that strong IR bands often correspond to weak Raman bands and vice versa, providing chemists with a powerful dual approach for comprehensive molecular characterization.

Fundamental Physical Mechanisms

IR Spectroscopy: Quantum Transitions Through Light Absorption

IR spectroscopy operates on the principle of absorption of infrared radiation when the energy of incident photons matches the energy required to excite a molecular bond to a higher vibrational energy state. For a vibration to be IR-active, it must result in a change in the dipole moment of the molecule [1] [3]. When IR radiation passes through a sample, specific frequencies are absorbed that correspond to the natural vibrational frequencies of the chemical bonds present, with the absorption process following the quantum mechanical selection rules that govern these transitions.

The technical implementation typically involves Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectrometers, which use a Michelson interferometer to simultaneously collect spectral data across a wide wavelength range, then apply a Fourier transform to convert the interferogram into a conventional spectrum [3]. This approach provides significant advantages in signal-to-noise ratio and measurement speed compared to traditional dispersive instruments.

Raman Spectroscopy: Inelastic Scattering of Photons

Raman spectroscopy relies on the inelastic scattering of monochromatic light, typically from a laser source in the visible or near-infrared range. When photons interact with molecules, most are elastically scattered (Rayleigh scattering) at the same energy as the incident light. However, approximately 1 in 10⁷ photons undergo inelastic scattering, where energy is either lost to or gained from molecular vibrations, resulting in scattered light of different frequencies known as Raman shifts [1] [2].

The Raman effect occurs because the incident laser light temporarily excites the molecule to a "virtual" energy state, from which it can return to a different vibrational level, emitting a photon with energy different from the incident photon. Energy loss to molecular vibrations produces Stokes lines (lower energy than incident light), while energy gain from molecular vibrations produces anti-Stokes lines (higher energy) [2]. The resulting Raman spectrum represents these energy shifts relative to the excitation laser frequency, typically reported in wavenumbers (cm⁻¹).

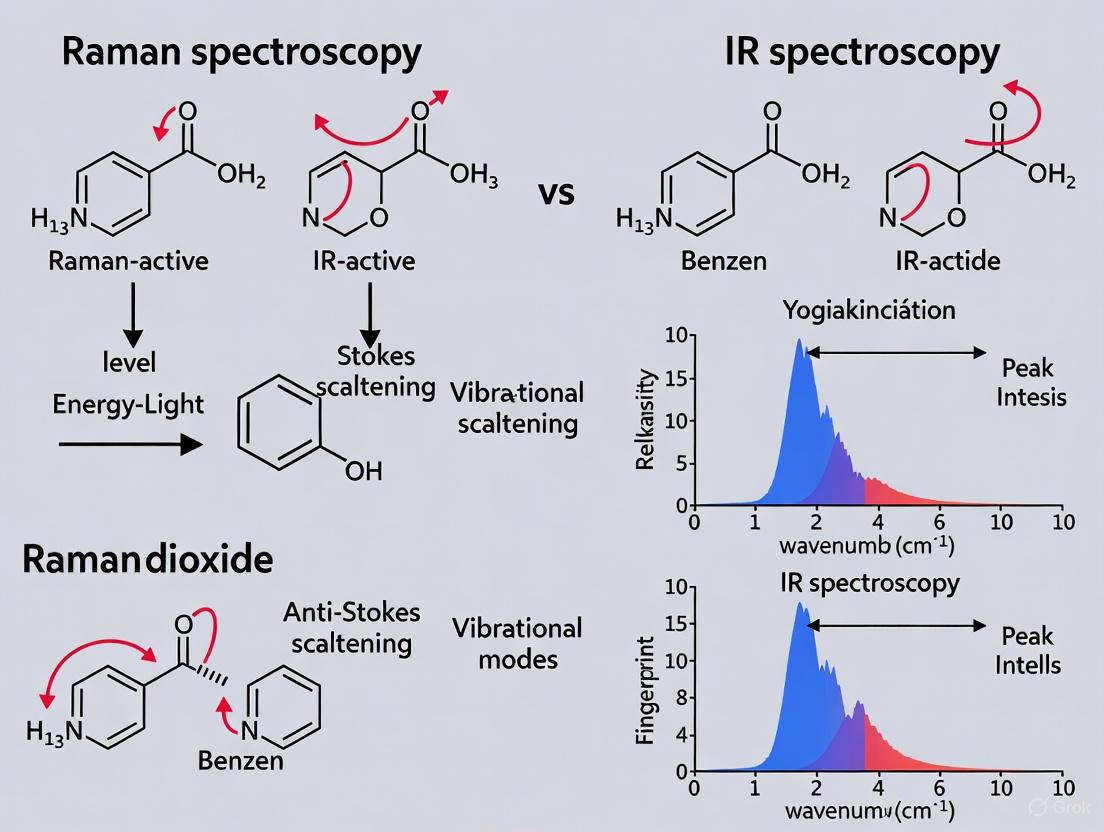

Comparative Physical Mechanisms Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental physical processes underlying IR absorption and Raman scattering:

Experimental Comparison: Key Parameters and Performance

Direct Technique Comparison

Table 1: Fundamental comparison of IR and Raman spectroscopy techniques

| Parameter | IR Spectroscopy | Raman Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Principle | Light absorption | Inelastic light scattering |

| Energy Transition | Direct vibrational energy level transition | Virtual energy state transition |

| Selection Rule | Change in dipole moment | Change in polarizability |

| Sensitivity | Polar bonds (e.g., C=O, O-H, N-H) | Non-polar bonds (e.g., C=C, S-S, C≡C) |

| Water Compatibility | Strong water interference | Minimal water interference |

| Spatial Resolution | Diffraction-limited (several to ~15 μm) | Submicron possible |

| Sample Preparation | Often requires specific cells (ATR) or thin samples | Minimal preparation; works in reflection mode |

| Key Limitations | Strong water absorbance, spectral artifacts in reflection | Fluorescence interference, weak signal |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Long-Term Stability Assessment Protocol for Raman Systems

A comprehensive investigation into Raman device stability involved weekly measurements of 13 stable reference substances over ten months to characterize instrumental variations over time [4]. The experimental protocol included:

- Reference Materials: Four standard references (cyclohexane, paracetamol, polystyrene, silicon), four solvents (DMSO, benzonitrile, isopropanol, ethanol), three carbohydrates (fructose, glucose, sucrose), and two lipids (squalene, squalane) selected for stability and coverage of spectral features relevant to biological samples [4].

- Measurement Parameters: Approximately 50 Raman spectra per substance were acquired weekly using a high-throughput screening Raman system (HTS-RS) equipped with a 785 nm excitation laser at 400 mW output power with 1-second integration time [4].

- Data Analysis Pipeline: Stability was benchmarked through intensity variations, correlation coefficients, clustering, and classification accuracy. Computational methods including variational autoencoders (VAE) and extensive multiplicative scattering correction (EMSC) were employed to estimate and suppress spectral variations [4].

High-Throughput Raman Screening Protocol

Recent advances in automated Raman systems have enabled high-throughput screening essential for bioprocess development and pharmaceutical applications:

- System Configuration: An integrated system simultaneously handles eight parallel samples delivered by a pipetting robot, completing measurement, handling, cleaning, and concentration prediction within 45 seconds per sample [5].

- Sample Handling: Chemically inert PTFE sampling interface with 8 wells holding 125 μL volumes, connected through a 12-to-1 bidirectional valve multiplexer to a flow-through cuvette for spectral measurement [5].

- Spectral Acquisition: Metrohm i-Raman Plus 785 Spectrometer with 785 nm excitation wavelength, 455 mW laser power, measuring spectra from 65 cm⁻¹ to 3350 cm⁻¹ with 2048 dimensions [5].

- Machine Learning Integration: Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) predict metabolite concentrations from Raman spectra, achieving mean absolute errors of 0.27 g L⁻¹ for glucose and 0.06 g L⁻¹ for acetate during Escherichia coli cultivations [5].

Quantitative Performance Data

Table 2: Experimental performance metrics for IR and Raman spectroscopy

| Performance Metric | IR Spectroscopy | Raman Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|

| Spectral Acquisition Time | Seconds to minutes | 1 second to 5 minutes per spectrum [4] [5] |

| Detection Sensitivity | High for polar functional groups | Weaker signal, enhanced by SERS |

| Spatial Resolution | 3-15 μm [1] | Submicron possible [1] |

| Accuracy in Structure Elucidation | 63.79% Top-1 accuracy with AI [6] | Varies by application |

| Water Interference | Strong absorption | Minimal interference [7] |

| Fluorescence Interference | Not typically affected | Significant challenge [1] |

Advanced Applications and Research Frontiers

Pharmaceutical Applications

Vibrational spectroscopy serves critical roles in pharmaceutical development and quality control:

- Drug Polymorph Identification: Both techniques detect crystalline forms and hydrates critical for drug stability and bioavailability [3].

- Formulation Analysis: FTIR-ATR spectroscopy enables quantification of active ingredients in semi-solid formulations and tablets without extensive sample preparation [3].

- Drug Release Monitoring: FTIR-ATR techniques non-invasively monitor drug release kinetics from topical formulations and penetration enhancement effects [3].

AI-Enhanced Spectral Analysis

Recent breakthroughs in artificial intelligence have dramatically advanced spectroscopic capabilities:

- Structure Elucidation from IR: Transformer models now achieve 63.79% Top-1 and 83.95% Top-10 accuracy in predicting molecular structures directly from IR spectra by combining chemical formulas with spectral data [6].

- Spectral Interpretation: Machine learning models extract substantially more information from the complex fingerprint region (400-1500 cm⁻¹) of IR spectra than traditional manual interpretation [8].

- High-Throughput Analysis: Integration of PCA with machine learning classifiers enables rapid automated identification of complex mixtures in Raman and SERS spectra [9].

Experimental Workflow for Automated Analysis

The following diagram illustrates a modern high-throughput spectroscopy workflow incorporating automation and machine learning:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Solutions

Reference Materials and Calibration Standards

Table 3: Essential research reagents and materials for vibrational spectroscopy

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Cyclohexane | Wavenumber calibration standard | Raman spectrometer calibration [4] |

| Polystyrene | Intensity and wavenumber reference | Validation of spectral accuracy [4] |

| Paracetamol | Solid reference material | Monitoring focusing stability [4] |

| Silicon Wafer | Intensity calibration | Exposure time calibration via 520 cm⁻¹ band [4] |

| Gold Nanoparticles (GNPs) | Surface-enhanced Raman scattering | Signal amplification for trace detection [9] |

| ATR Crystals (Diamond/Ge) | Internal reflection element | FTIR-ATR measurements [3] |

| Deuterated Solvents | IR-transparent solvents | FTIR sample preparation without interference |

Emerging Technology Solutions

- O-PTIR (Optical Photothermal IR): Breakthrough technology enabling simultaneous submicron IR and Raman spectroscopy, overcoming traditional IR diffraction limits by detecting photothermal effects with a visible probe beam [1].

- Handheld Spectrometers: Portable devices enabling in-situ analysis for applications ranging from artwork authentication to hazardous material identification [2].

- Multi-modal Systems: Integrated platforms combining complementary techniques such as IR+Raman+Fluorescence for comprehensive sample characterization [1].

The physics of light interaction—whether through scattering or absorption—defines the distinctive capabilities and applications of Raman and IR spectroscopy. While their fundamental mechanisms differ, these techniques provide complementary molecular information that makes them invaluable tools for scientific research and industrial applications. Recent advancements in automation, artificial intelligence, and integrated systems have significantly enhanced their power and accessibility, enabling more sophisticated analyses and broader implementation across diverse fields from pharmaceutical development to environmental monitoring. The continued evolution of both technologies promises even greater capabilities for molecular characterization and structure elucidation in the coming years.

Vibrational spectroscopy is a cornerstone of molecular analysis in scientific research and drug development. While both Raman and Infrared (IR) spectroscopy probe molecular vibrations to provide a structural fingerprint, they are governed by fundamentally different selection rules. This guide provides an objective comparison of these techniques, explaining the core physics behind their selection rules and the practical implications for their application.

The Core Physics: Understanding the Fundamental Selection Rules

The selection rule—the physical principle that determines whether a specific molecular vibration can be observed—is the most significant difference between Raman and IR spectroscopy.

- IR Spectroscopy requires a change in the dipole moment of the molecule during the vibration [10] [11]. A dipole moment exists due to the separation of positive and negative charges within a molecule. For a vibration to be IR-active, the asymmetric stretching or bending of bonds must alter this charge separation, allowing the molecule to absorb infrared radiation directly [10] [12].

- Raman Spectroscopy depends on a change in polarizability [10] [13]. Polarizability refers to the ease with which an external electric field (like that from a laser) can distort the electron cloud of a molecule [10] [14]. For a vibration to be Raman-active, the molecular motion must change how easily the electron cloud can be deformed [13] [14].

This distinction means the two techniques often provide complementary information. A vibration that does not cause a change in dipole moment (and is thus IR-inactive) may still cause a significant change in polarizability, making it Raman-active, and vice-versa [13].

Visualizing the Mechanisms

The diagram below illustrates the different energy transitions and physical interactions that underpin IR absorption and Raman scattering.

Experimental Evidence and Comparative Data

The theoretical principles of selection rules are clearly demonstrated in experimental data. The symmetric stretch of carbon dioxide (CO₂) is a classic example that shows the complementary nature of these techniques.

Case Study: Carbon Dioxide (CO₂) Vibrations

| Vibration Mode | IR Active | Raman Active | Physical Reason |

|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetric Stretch | No [10] [14] | Yes [10] [14] | No net change in dipole moment; large change in molecular polarizability [14]. |

| Asymmetric Stretch | Yes [10] [14] | No [10] [14] | Net change in dipole moment; changes in bond polarizability cancel out [14]. |

| Bending | Yes [10] | No [14] | Change in dipole moment; no change in bond length, hence no polarizability change [14]. |

Characteristic Spectral Bands in Drug Development

The following table summarizes how different functional groups, critical in pharmaceutical compounds, respond to each technique based on their bond polarity and polarizability.

| Functional Group/Bond | IR Sensitivity | Raman Sensitivity | Key Application in Drug Development |

|---|---|---|---|

| O-H, N-H | Strong [10] [15] | Weak | Tracking hydration state, amine salt formation [11] [15]. |

| C=O | Strong [10] [15] | Weak | Monitoring ester hydrolysis, ketone reactivity [11]. |

| C-C, C=C | Weak | Strong [15] [12] | Characterizing carbon skeleton, polymorphism, crystallinity [16]. |

| S-S | Weak | Strong | Confirming disulfide bridge formation in biologics [12]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Material Analysis

To ensure reproducible and high-quality data, the following protocols outline standard procedures for acquiring and analyzing Raman and IR spectra.

Protocol 1: Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy

Principle: Measure the frequencies of IR light absorbed by the sample as bonds vibrate [15].

- Sample Preparation:

- Solid Powders: Grind 1-2 mg of sample with ~100 mg of dry potassium bromide (KBr). Hydraulic press is used to form a transparent pellet for transmission analysis [11].

- Aqueous Solutions: Use an Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR) accessory with a diamond crystal. Ensure the sample is in firm contact with the crystal. Path length is minimized to <10 µm to mitigate strong water absorption [11].

- Thin Films: Analyze directly via ATR-FTIR [11].

- Data Acquisition: Acquire spectrum over 4000-400 cm⁻¹ range. A background spectrum (ambient air or clean ATR crystal) is collected and automatically subtracted from the sample spectrum [11].

- Data Analysis: Identify functional groups by correlating absorption band positions (e.g., Amide I band ~1650 cm⁻¹ for proteins) with known group frequencies [11].

Protocol 2: Raman Spectroscopy

Principle: Measure the energy shift of monochromatic laser light inelastically scattered by the sample [13] [15].

- Sample Preparation:

- Minimal preparation is typically required [12]. Solids, liquids, and powders can often be analyzed directly.

- Aqueous solutions are ideal for Raman as water is a weak scatterer. Samples can be analyzed in glass vials or directly in a well plate [10].

- Note: Colored samples may absorb laser energy and cause thermal degradation; test with lower laser power or different wavelengths (e.g., NIR 785 nm laser) to mitigate fluorescence [10] [13].

- Data Acquisition: Irradiate the sample with a focused laser beam. Collect the scattered light and pass it through a notch filter to remove the intense Rayleigh line. The remaining Raman-shifted light is dispersed onto a CCD detector [13].

- Data Analysis: Peaks in the Raman spectrum are reported as Raman shift (cm⁻¹) from the laser line. Band positions and relative intensities provide information on molecular structure and polymorphism [13] [14].

Visualizing the Complementary Workflow

The logical workflow for selecting the appropriate technique based on sample properties and information goals is outlined below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful vibrational spectroscopy requires specific instrumentation and consumables. The following table details key items and their functions in the experimental workflow.

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| FTIR Spectrometer with ATR | Enables analysis of aqueous samples and solids with minimal preparation by measuring the interaction of an evanescent wave with the sample [11]. |

| Raman Spectrometer (785 nm laser) | Standard for biological and pharmaceutical samples to minimize fluorescence interference while providing sufficient Raman scattering intensity [10] [13]. |

| Potassium Bromide (KBr) | Infrared-transparent matrix used to prepare solid samples for transmission FTIR analysis [11]. |

| Notch/Edge Filters | Critical optical components in Raman spectrometers that filter out the intense elastically scattered Rayleigh light, allowing the weak Raman signal to be detected [13]. |

Performance Comparison: Advantages and Limitations in Practice

The fundamental differences in selection rules translate directly into distinct practical advantages and limitations, guiding researchers on which technique to apply for specific challenges.

| Parameter | IR Spectroscopy | Raman Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity to Water | High absorption interferes with measurements [10] [11]. | Weak scattering allows direct analysis of aqueous solutions [10] [11]. |

| Fluorescence Interference | Not an issue, as IR radiation does not induce electronic excitation [10]. | A significant problem; fluorescence can be orders of magnitude stronger than the Raman signal, obscuring it [10] [12]. |

| Sensitivity to Functional Groups | Excellent for polar bonds (O-H, N-H, C=O) [10] [15]. | Excellent for non-polar, covalent bonds (C-C, C=C, S-S) [15] [12]. |

| Sample Preparation | Can require careful preparation (e.g., KBr pellets, controlled path lengths) [11] [12]. | Typically minimal; can often analyze samples directly through glass packaging [12]. |

| General Sensitivity | Generally more sensitive for low-concentration analytes in many configurations [10]. | Can suffer from inherently weak signal, though techniques like SERS provide massive enhancement [13]. |

For researchers in drug development, the choice is often not between one technique or the other, but how to use them together. Their complementary nature, rooted in their distinct selection rules, provides a more complete picture of a sample's molecular structure, conformation, and environment [10] [15].

In the realm of molecular analysis, infrared (IR) and Raman spectroscopy stand as cornerstone analytical techniques for determining molecular structures and dynamics. Both methods probe the vibrational modes of molecules, providing unique yet complementary insights that serve as a "fingerprint" for chemical identification [1] [2]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding how to interpret the characteristic peaks and complex fingerprint regions from these techniques is fundamental to applications ranging from drug characterization and quality control to the analysis of biomarkers and advanced materials. This guide provides a detailed comparison of these two powerful spectroscopic methods, offering a structured framework for decoding the rich information contained within their spectral outputs.

While both techniques yield information on molecular vibrations, they arise from fundamentally different physical processes. IR spectroscopy measures the absorption of infrared light when a vibration causes a change in the dipole moment of a chemical bond [1]. In contrast, Raman spectroscopy relies on the inelastic scattering of light resulting from vibrations that cause a change in molecular polarizability [1] [13]. This fundamental difference in mechanism is the source of their complementarity; IR is generally more sensitive to polar functional groups, while Raman is often more sensitive to non-polar bonds and symmetric molecular vibrations [2].

Fundamental Principles and a Direct Comparison

The following diagram illustrates the complementary relationship and the fundamental physical principles underlying IR and Raman spectroscopy.

The core distinction lies in their underlying mechanisms, which directly informs their application strengths and weaknesses. The table below summarizes the key operational differences.

Table 1: Fundamental operational differences between IR and Raman spectroscopy

| Feature | IR Spectroscopy | Raman Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|

| Underlying Process | Absorption of IR light [1] | Inelastic scattering of monochromatic light [1] [2] |

| Selection Rule | Requires a change in dipole moment [1] [17] | Requires a change in polarizability [1] [13] |

| Sensitivity | Strong for polar bonds (e.g., C-O, O-H, N-H) [1] [17] | Strong for non-polar/covalent bonds (e.g., C-C, C=C, S-S) [1] [13] |

| Spatial Resolution | Diffraction-limited (~several to 15 µm) [1] | Can achieve submicron resolution [1] |

| Aqueous Samples | Challenging due to strong water absorption [1] | Well-suited due to weak water scattering [18] [7] |

| Main Interference | Water vapor, sample thickness [2] | Fluorescence from impurities or sample itself [1] [19] |

Characteristic Peak Identification and the Fingerprint Region

A critical skill in spectral interpretation is recognizing the characteristic peaks of common functional groups. These peaks typically appear in the group frequency region (approximately 1500–3500 cm⁻¹) and provide immediate clues about the molecular structure [20]. The table below catalogues the signature absorptions for key bonds.

Table 2: Characteristic vibrational frequencies for common functional groups in IR and Raman spectroscopy

| Functional Group/Bond | Vibration Mode | IR Absorption (cm⁻¹) | Raman Shift (cm⁻¹) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| O-H (Alcohol) | Stretch | 3230–3550 (broad, strong) [20] | Broad due to hydrogen bonding [20] | |

| O-H (Carboxylic Acid) | Stretch | 2500–3300 (very broad, strong) [20] | Very broad, often overlaps C-H [20] | |

| N-H | Stretch | 3300–3500 [17] | Primary amines show two bands [20] | |

| C-H (Alkane) | Stretch | 2850–3000 [21] [17] | [20] | |

| C≡N | Stretch | 2240–2260 (medium) [20] [17] | ~2250 [18] | Sharp peak [20] [18] |

| C≡C | Stretch | 2100–2260 (weak) [20] | [20] | |

| C=O | Stretch | 1630–1815 (strong) [20] | 1680–1820 [18] | Very strong, position varies by compound type [21] [20] |

| C=C (Alkene) | Stretch | 1620–1680 [20] | [20] | |

| C=C (Aromatic) | Stretch | 1550–1700 (medium) [20] | [20] | |

| C-N | Stretch | 1029–1250 [20] | [20] |

The region below 1500 cm⁻¹ is known as the fingerprint region and is critical for molecular identification [21] [20]. This spectral area contains a complex set of peaks arising from skeletal vibrations and single-bond stretches (C-C, C-O, C-N), as well as bending vibrations [21]. The pattern in this region is unique to every molecule, much like a human fingerprint, allowing for definitive identification by comparison to reference spectra [21]. In Raman spectroscopy, a specific sub-region from 1550–1900 cm⁻¹ has been identified as particularly valuable for identifying active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), as many common excipients show no Raman signals in this range, while APIs exhibit unique vibrations from functional groups like C=N, C=O, and N=N [18].

Experimental Protocols and Data Interpretation

Protocol for Differentiating APIs from Excipients Using Raman Spectroscopy

The following workflow outlines a specific experimental approach, derived from published research, for leveraging the "fingerprint in the fingerprint" region to identify an Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) in a solid dosage form [18].

Protocol for Functional Group Analysis using IR Spectroscopy

A systematic approach is required for accurate interpretation of IR spectra to identify unknown compounds [20].

- Sample Preparation: For liquids, a thin film can be sandwiched between two polished salt plates (e.g., NaCl). Solids may be ground to a paste with mineral oil (a Nujol mull) or pressed into a transparent disk with KBr [17].

- Spectral Acquisition: Collect the background spectrum and then the sample spectrum over the standard range of 4000–500 cm⁻¹.

- Data Interpretation Strategy:

- Analyze the Group Frequency Region First (3500–1500 cm⁻¹): Systematically check for the presence of key functional groups like O-H, N-H, C-H, and C=O by looking for characteristic peaks in their expected regions [21] [20].

- Consult Reference Tables: Use a table of characteristic frequencies to assign the observed absorptions [21].

- Examine the Fingerprint Region (1500–500 cm⁻¹): Use this region to confirm structural elements or identify a specific compound by comparing its unique pattern to a reference spectrum [21] [20].

- Cross-Check Evidence: Corroborate findings by ensuring the presence of all expected peaks for a suspected functional group and noting the absence of peaks that would rule it out [20].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and reagents commonly required for vibrational spectroscopy experiments in a research and development setting.

Table 3: Essential research reagents and materials for IR and Raman spectroscopy

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Experimental Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Polished Salt Plates (NaCl, KBr) | Windows for liquid and mull sample analysis in IR transmission mode [17]. | Hygroscopic; must be cleaned with dry solvent and stored in a desiccator [17]. |

| Potassium Bromide (KBr) | Matrix for creating solid sample disks under high pressure for IR transmission measurements [17]. | Must be of spectroscopic grade and scrupulously dry to avoid spectral interference from water. |

| ATR Crystals (Diamond, Ge) | Enable direct, non-destructive surface analysis of solids and liquids in Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR) IR mode [1]. | Diamond is robust but expensive; Germanium (Ge) offers high sensitivity for low-penetration depth studies [1]. |

| Nujol (Mineral Oil) | A purified hydrocarbon oil used to prepare mulls of solid powder samples for IR analysis [17]. | Its own C-H absorptions will appear in the spectrum and must be accounted for. |

| Deuterated Solvents (CDCl₃, D₂O) | IR-transparent solvents for analyzing samples in solution, avoiding interference from C-H or O-H stretches of protons [17]. | Essential for analyzing solution-phase structure and kinetics. |

| Reference Excipient Library | A collection of spectra from common inactive ingredients (e.g., lactose, magnesium stearate) [18]. | Vital for differentiating API signals from excipient backgrounds in pharmaceutical analysis [18]. |

The choice between IR and Raman spectroscopy is not a matter of one being universally superior to the other, but rather which is best suited to the specific analytical question and sample properties.

- Choose IR spectroscopy when your analysis requires high sensitivity to polar functional groups (like C=O, O-H, N-H), when sample fluorescence is a concern, or when cost-effectiveness is a primary consideration [1] [2]. It is the established workhorse for routine qualitative analysis of organic compounds.

- Choose Raman spectroscopy when you need to analyze aqueous solutions directly, require high spatial resolution (down to the submicron level), or are investigating symmetric molecular vibrations and non-polar bonds (like C-C, C=C, S-S) that are weak in IR [1] [2] [7]. It is also ideal for samples that require minimal preparation and when analyzing through transparent packaging [18].

Ultimately, IR and Raman spectroscopy are powerfully complementary. The convergence of these techniques, as seen in emerging technologies like Optical Photothermal Infrared (O-PTIR), which allows for simultaneous IR and Raman data collection from the same submicron spot, represents the future of vibrational analysis, offering researchers a more comprehensive and unambiguous chemical profile of their samples [1].

In the analytical toolkit of researchers and drug development professionals, infrared (IR) and Raman spectroscopy stand as two pivotal vibrational spectroscopy techniques. While each can be used independently, their true power is unlocked when used together, governed by a fundamental tenet known as the complementarity principle. This principle states that the vibrational modes active in IR spectroscopy are those accompanied by a change in the molecule's dipole moment, whereas those active in Raman spectroscopy involve a change in polarizability during vibration [2] [22]. Often, vibrational modes that are weak or silent in one technique are strong in the other. Consequently, employing both methods provides a more complete vibrational fingerprint of a sample, enabling a fuller characterization of molecular structures and dynamics that is greater than the sum of its parts. This guide objectively compares the performance of these two techniques, supported by experimental data and protocols relevant to scientific and industrial applications.

Fundamental Principles and a Direct Comparison

At their core, both IR and Raman spectroscopy probe the vibrational states of molecules, but they do so through different physical mechanisms.

- IR Spectroscopy is an absorption technique. It measures how much infrared light is absorbed by a molecule when the light's energy causes a change in the dipole moment of a chemical bond, exciting it to a higher vibrational energy level [2] [22].

- Raman Spectroscopy is a scattering technique. It relies on the inelastic scattering of monochromatic light (usually from a laser). When the scattered light loses or gains energy corresponding to a molecular vibration, it provides a Raman spectrum. This requires a change in the polarizability, or the deformation of the electron cloud, of a molecule during vibration [2] [22].

The selection rules lead to their complementary nature. Antisymmetric vibrations and bonds with strong permanent dipole moments (e.g., O-H, C=O, N-H) typically yield strong IR signals. In contrast, symmetric vibrations and bonds in homo-nuclear molecules (e.g., C=C, C≡C, S-S) that are associated with a large change in polarizability are strong in Raman [2]. This is why using both techniques is essential for a comprehensive analysis.

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of IR and Raman Spectroscopy.

| Feature | IR Spectroscopy | Raman Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|

| Underlying Principle | Absorption of IR light | Inelastic scattering of monochromatic light |

| Physical Requirement | Change in dipole moment | Change in polarizability |

| Spectral Range | Mid-infrared (e.g., 400-4000 cm⁻¹) | Typically 400-4000 cm⁻¹ (Stokes shift) |

| Key Strength | Sensitive to polar functional groups | Sensitive to homo-nuclear covalent bonds |

| Water Compatibility | Poor (strong absorber) | Good (weak scatterer) |

| Sample Preparation | Can require specific cells or pellets | Minimal; can analyze through glass/plastic |

Performance and Applicative Comparison

The theoretical differences translate into distinct practical advantages and limitations, which determine the suitability of each technique for specific applications, particularly in pharmaceuticals and material science.

Comparative Advantages and Limitations

A key practical advantage of Raman spectroscopy is its minimal interference from water, allowing for the direct analysis of aqueous solutions and biological samples [7] [22]. It also offers flexibility for remote sensing using fiber optics and can analyze samples through glass or plastic containers. However, Raman is generally a less sensitive technique than IR, and its signal can be overwhelmed by fluorescence from the sample or impurities [2] [19]. Furthermore, the high-powered lasers used can, in some cases, cause thermal degradation of the sample [22].

IR spectroscopy, while highly sensitive and often more cost-effective [22], is notoriously susceptible to interference from water vapor and requires careful sample handling to control thickness. It is less suited for analyzing aqueous solutions directly and typically offers a lower spatial resolution compared to Raman when coupled with microscopy [19].

Quantitative Performance in Pharmaceutical Analysis

Direct comparisons in scientific studies highlight their performance nuances. One study compared Near-Infrared (NIR) and Raman imaging for predicting the drug release rate from sustained-release tablets. The study found that while both techniques could accurately predict dissolution profiles, Raman imaging provided clearer boundaries of particles and was better for components with low concentrations. In contrast, NIR instrumentation allowed for faster measurements, making it a stronger candidate for real-time process monitoring [19].

Another study evaluating the accuracy of concentration determination in powdered mixtures under different packing densities found that Raman schemes with wide-area illumination (WAI) were less sensitive to variations in packing density compared to NIR spectroscopy. This makes WAI-Raman more robust for analyzing samples with inconsistent physical properties [23].

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison in Key Application Areas.

| Application Area | IR Performance & Notes | Raman Performance & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Aqueous Solutions | Poor; strong water absorption obscures solute signal [22]. | Excellent; water is a weak scatterer, allowing solute analysis [7]. |

| Pharmaceutical Powder Blends | NIR is fast but sensitive to packing density; broader spectral bands [23]. | High specificity; less sensitive to packing density with WAI; sharper bands [19] [23]. |

| Polymer & Material Analysis | Effective for identifying polar functional groups. | Superior for characterizing carbon backbones (e.g., C-C, C=C) [2]. |

| Sensitivity | Generally high sensitivity [22]. | Inherently weak signal; often requires enhancement (e.g., SERS) [22]. |

Experimental Protocols and Data Interpretation

To illustrate the practical application of the complementarity principle, consider an experiment aimed at characterizing an unknown compound in a drug development setting.

Sample Analysis Workflow

The following diagram outlines a generalized experimental workflow that leverages both techniques.

Detailed Methodologies

The protocols below are adapted from recent research to provide concrete, actionable methodologies.

Protocol 1: Determination of Chlorogenic Acid in a Protein Matrix [24]

- Objective: To rapidly and non-destructively monitor the content of chlorogenic acid (CGA) in sunflower meal, a protein-rich by-product.

- Sample Preparation: For Raman analysis, CGA standard was mixed with Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) or defatted sunflower meal (SFM) to create model samples with concentrations ranging from 1% to 10% w/w. The mixtures were compacted into tablets using a hydraulic press. For IR analysis, 2 mg of sample was mixed with 148 mg of KBr and pressed into a pellet.

- Instrumentation & Data Acquisition:

- Raman: Spectra were acquired using a confocal Raman microscope (Horiba LabRAM HR Evolution) with a 532 nm laser. Mapping was performed on a 10x10 grid with a 555 µm step size, 10s accumulation time, and 2 accumulations.

- IR (FTIR): Spectra were recorded in transmission mode using a Perkin Elmer Spectrum 3 FTIR spectrometer in the range of 4,000–400 cm⁻¹.

- Results & Complementarity: The study successfully developed calibration models for both techniques. IR spectroscopy demonstrated a lower limit of detection (LOD) for CGA at 0.75 wt%, whereas Raman spectroscopy had an LOD of 1 wt%. This highlights IR's superior sensitivity for this specific quantitative application, while Raman provided a viable, non-destructive alternative.

Protocol 2: Chemical Imaging and Dissolution Profile Prediction of Tablets [19]

- Objective: To compare NIR and Raman chemical imaging for predicting the dissolution profile of sustained-release tablets based on the concentration and particle size of hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC).

- Sample Preparation: Tablets were manufactured with varying concentrations and particle sizes of HPMC.

- Instrumentation & Data Acquisition:

- Raman & NIR Imaging: Hyperspectral images (chemical maps) of the tablet surfaces were collected using both techniques.

- Data Processing: The chemical images were processed using Classical Least Squares (CLS) to determine the average HPMC concentration. A Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) was then applied to the same images to extract information on the particle size of HPMC.

- Results & Complementarity: Both imaging techniques provided accurate predictions of the tablet's dissolution profile. Raman imaging yielded a slightly higher average similarity factor (f2 = 62.7) compared to NIR imaging (f2 = 57.8). However, the study concluded that NIR imaging's significantly faster measurement speed made it more suitable for real-time, in-line quality control, whereas Raman provided superior spectral resolution for R&D characterization.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Instruments

A practical comparison guide must account for the essential tools required for experimentation.

Table 3: Key Reagents and Instruments for IR and Raman Spectroscopy.

| Item / Solution | Function / Role in Analysis |

|---|---|

| FTIR Spectrometer | Core instrument for IR analysis; measures absorption of IR radiation by the sample [24]. |

| Raman Spectrometer/Microscope | Core instrument for Raman analysis; measures inelastically scattered light from a laser source [24]. |

| Potassium Bromide (KBr) | Used for preparing transparent pellets for transmission-mode FTIR analysis [24]. |

| Hydraulic Press | Used to compress powdered samples with KBr (for IR) or alone (for Raman mapping) into solid pellets for stable analysis [24]. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | A standard protein used to create model protein matrices for method development, e.g., analyzing drug-protein interactions [24]. |

| ChEMBL Database | A public repository of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties, used as a source for molecular structures for computational spectroscopy [16]. |

| Gaussian 09 Software | A quantum chemistry program used for computational calculation of theoretical IR and Raman spectra (e.g., at PBEPBE/6-31G level of theory) [16]. |

The Modern Frontier: Integration with Machine Learning

The combination of vibrational spectroscopy with artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) represents a significant leap forward. Deep learning algorithms, such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Transformers, are revolutionizing Raman spectral analysis by automatically identifying complex patterns in noisy data, reducing the need for manual feature extraction and preprocessing [25] [26].

In pharmaceutical analysis, AI-powered Raman spectroscopy is advancing drug development, impurity detection, and clinical diagnostics. These models can predict dissolution profiles of tablets from chemical images [19] and are being used for early disease detection by identifying biomarkers [25]. A key challenge remains the "black box" nature of some complex models, driving research into interpretable AI methods, such as attention mechanisms, to enhance transparency for regulatory and clinical use [25]. Similar ML approaches are being applied to IR spectroscopy to enhance spectral interpretation and accelerate data analysis workflows [2].

IR and Raman spectroscopy are not competing technologies but are inherently complementary partners in molecular analysis. IR excels at detecting polar functional groups, while Raman is superior for probing symmetric vibrations and covalent molecular backbones. As demonstrated, the choice between them—or the decision to use both—depends on the sample properties, the specific information required, and practical constraints like cost, speed, and the need for aqueous analysis. The ongoing integration of these techniques with machine learning and computational chemistry is further amplifying their power, enabling smarter, faster, and more informative analyses that are indispensable for modern scientific research and drug development.

Techniques in Action: Methodologies and Cutting-Edge Applications in Biomedicine and Pharma

Raman spectroscopy has emerged as a powerful analytical technique in biomedical research, particularly for cancer diagnostics and liquid biopsy analysis. This label-free, non-destructive method provides detailed molecular fingerprint information from biological samples by measuring inelastic scattering of monochromatic light. Unlike traditional diagnostic methods that often require extensive sample preparation and staining, Raman spectroscopy enables direct analysis of cells, tissues, and biofluids while preserving sample integrity. The technique's exceptional molecular specificity allows researchers to detect subtle biochemical changes associated with carcinogenesis, often before morphological alterations become apparent. Furthermore, the minimal interference from water molecules makes Raman spectroscopy particularly suitable for analyzing biological specimens and aqueous solutions [7] [2].

The clinical application of Raman spectroscopy has gained significant momentum with technological advancements in instrumentation, data processing, and artificial intelligence. Modern Raman systems have evolved from bulky laboratory instruments to compact, portable devices suitable for clinical settings and even intraoperative use. These developments, coupled with enhanced computational power for spectral analysis, have positioned Raman spectroscopy as a transformative tool in oncology. Current research explores its utility across the cancer care continuum – from early detection and diagnosis to surgical guidance and treatment monitoring [27] [28]. The technique's ability to provide real-time, objective diagnostic information addresses critical limitations of conventional histopathological methods, which are often time-consuming, subjective, and limited to single-timepoint assessments.

Fundamental Principles: Raman versus IR Spectroscopy

Infrared (IR) and Raman spectroscopy are complementary vibrational spectroscopy techniques that provide molecular structural information through different physical mechanisms. Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy operates based on light absorption. When IR radiation interacts with a molecule, energy is absorbed when the frequency matches the vibrational frequency of chemical bonds, but only if the vibration causes a change in the dipole moment of the molecule. This makes FTIR particularly sensitive to polar functional groups such as O-H, N-H, and C=O, which are abundant in biological systems. The resulting spectrum represents these absorption patterns, providing a molecular fingerprint of the sample [1] [29].

In contrast, Raman spectroscopy relies on inelastic scattering of monochromatic light. When photons interact with molecules, most are elastically scattered (Rayleigh scattering), but approximately one in 10^6-10^8 photons undergoes inelastic scattering, resulting in energy shifts corresponding to molecular vibrational energies. This Raman effect occurs when molecular vibrations cause a change in polarizability rather than dipole moment. Consequently, Raman spectroscopy is particularly sensitive to symmetric molecular vibrations and non-polar bonds, such as C-C, C=C, and S-S, which are abundant in biological macromolecules including proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids. The resulting spectrum displays these energy shifts as peaks representing specific molecular vibrations [27] [2].

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between Raman and IR Spectroscopy

| Characteristic | Raman Spectroscopy | FTIR Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Principle | Inelastic light scattering | Light absorption |

| Molecular Requirement | Change in polarizability | Change in dipole moment |

| Spectral Resolution | High (sharp peaks) | Moderate (broader peaks) |

| Water Compatibility | Excellent (weak scatterer) | Poor (strong absorber) |

| Spatial Resolution | High (submicron with microscopes) | Lower (diffraction-limited, several microns) |

| Sample Preparation | Minimal (works through glass/plastic) | Often requires specific substrates or ATR crystal contact |

| Key Strengths | Symmetric bonds, aqueous samples, fingerprint region | Polar functional groups, high sensitivity |

The complementary nature of these techniques arises from their different selection rules. Molecular vibrations that are strong in IR may be weak in Raman, and vice versa. For instance, the symmetric stretching vibration of homonuclear diatomic molecules (e.g., O₂, N₂) is Raman-active but IR-inactive, while the asymmetric stretching of heteronuclear bonds (e.g., C=O, O-H) is typically strong in IR but weak in Raman. This complementarity provides a more comprehensive molecular understanding when both techniques are employed [1] [29] [2].

Recent technological innovations have enabled simultaneous IR and Raman measurement through Optical Photothermal Infrared (O-PTIR) spectroscopy. This technique overcomes the diffraction limit of traditional IR systems by detecting photothermal effects induced by IR absorption using a visible probe beam. O-PTIR provides submicron spatial resolution for IR measurements and allows simultaneous collection of IR and Raman spectra from the exact same sample location, eliminating registration uncertainties and providing truly correlative molecular information [1].

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Raman Spectroscopy Modalities for Biomedical Analysis

Several advanced Raman techniques have been developed to address specific challenges in biomedical analysis:

Confocal Raman Microscopy enhances spatial resolution by incorporating a pinhole aperture to eliminate out-of-focus light, enabling high-resolution depth sectioning of samples. This approach is particularly valuable for analyzing stratified tissues or creating three-dimensional chemical maps of cells and tissue sections. The high spatial resolution (approximately 2 μm) comes at the cost of increased acquisition time, especially at greater focal depths. Confocal Raman probes are commonly utilized for in vitro studies with cells and ex-vivo sample analysis [27].

Spatially Offset Raman Spectroscopy (SORS) enables non-invasive probing of deeper tissue layers by spatially separating the excitation and collection points. Conventional Raman spectroscopy typically samples depths of several hundred microns, while SORS effectively measures Raman signals from depths up to several millimeters. This technique collects Raman scattered photons that undergo multiple scattering events as they travel from deeper layers to the sample surface. While greater spatial offsets enable sampling from deeper tissues, they result in reduced signal intensity. SORS shows particular promise for intraoperative applications where subsurface tumor margins must be assessed without tissue sectioning [27].

Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) dramatically improves sensitivity through plasmonic enhancement when analytes are adsorbed onto nanostructured metal surfaces (typically gold or silver). The enhancement mechanisms include electromagnetic enhancement (10^6-10^8 factor) from localized surface plasmon resonance and chemical enhancement (10^1-10^3 factor) from charge transfer between the molecule and metal surface. This signal amplification enables single-molecule detection in some cases and is particularly valuable for analyzing low-abundance biomarkers in complex biological fluids. SERS can be implemented in two primary approaches: label-free detection, where intrinsic molecular fingerprints are enhanced, and indirect detection using SERS tags with Raman reporter molecules for highly sensitive and multiplexed assays [30] [31] [28].

Coherent Raman Spectroscopy, including Coherent Anti-Stokes Raman Scattering (CARS) and Stimulated Raman Scattering (SRS), represents a class of nonlinear techniques that provide significantly stronger signals than spontaneous Raman scattering. These methods employ multiple laser fields to coherently drive molecular vibrations, resulting in signals several orders of magnitude stronger than conventional Raman. While CARS and SRS offer superior speed and sensitivity for imaging applications, they require complex instrumentation with multiple pulsed lasers and specialized spectral processing. A particular challenge for biological applications is the non-resonant background in CARS, which can complicate spectral interpretation, especially in aqueous environments [27].

Experimental Protocols for Exosome Analysis via SERS

Exosome analysis using SERS involves a multi-step process from sample collection to spectral interpretation:

1. Sample Collection and Exosome Isolation: Blood samples are collected using standard venipuncture techniques into EDTA or citrate tubes to prevent coagulation. Plasma is separated by centrifugation (typically 2,000-3,000 × g for 20 minutes) to remove cells and debris. Exosomes are then isolated from plasma using size exclusion chromatography (SEC), which separates vesicles based on hydrodynamic size while preserving their structural integrity and minimizing contamination from lipoproteins and other soluble proteins. SEC offers advantages over other isolation methods by avoiding chemical reagents that could interfere with subsequent label-free SERS detection. The exosome-containing fractions are identified through Western blotting for characteristic markers (CD9, CD63, CD81, TSG101) and characterized by nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) to confirm size distribution (typically 100-150 nm) and concentration [32].

2. SERS Substrate Preparation: Gold nanoparticle (AuNP)-aggregated array chips serve as the enhancing substrate. Colloidal AuNPs are precipitated and applied to (3-aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES)-functionalized glass surfaces as 2.5-mm diameter dots. Each chip contains multiple detection spots (typically 10) to increase throughput. The substrate's enhancement factor is calibrated using standard analytes like rhodamine 6G (R6G), with typical enhancement factors reaching 4.28 × 10^5. Uniformity is validated by measuring signal variation across the substrate surface, with quality control standards requiring a coefficient of variation below 10% at characteristic Raman bands [32].

3. SERS Measurement and Spectral Acquisition: Isolated exosome suspensions are deposited onto the SERS substrate dots and allowed to dry thoroughly. Raman spectra are collected using a Raman microscope system equipped with a 785 nm or 633 nm laser source. For each sample, 100 spectra are typically scanned from different locations to capture statistical variations and ensure representative sampling. Integration times range from 1-10 seconds per spectrum, with laser power optimized to avoid sample degradation while maintaining sufficient signal-to-noise ratio [32].

4. Data Processing and Analysis: Raw spectra undergo preprocessing including cosmic ray removal, background subtraction, and vector normalization. Anomalous spectra resulting from irregular substrate areas or contamination are filtered out. Processed spectra are then analyzed using machine learning algorithms, typically convolutional neural networks (CNN) in a multiple instance learning framework. The model is trained to classify spectra as cancerous or normal based on collective patterns from the 100 scans per sample, with the average prediction score used as the diagnostic criterion [32].

SERS-Based Exosome Analysis Workflow

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Cancer Diagnostic Performance Across Technologies

Raman spectroscopy demonstrates competitive performance compared to established diagnostic techniques across multiple cancer types. The following table summarizes key performance metrics from recent studies:

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Cancer Diagnostic Techniques

| Cancer Type | Technique | Sample Type | Sensitivity | Specificity | AUC | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple Cancers (6 types) | Exosome-SERS-AI | Plasma | 90.2% | 94.4% | 0.970 (cancer presence)0.945 (tissue of origin) | [32] |

| Endometrial Cancer | Raman ('wet' plasma) | Blood Plasma | - | - | 82% (accuracy) | [33] |

| Endometrial Cancer | ATR-FTIR ('wet' plasma) | Blood Plasma | - | - | 78% (accuracy) | [33] |

| Endometrial Cancer | Combined Raman & FTIR | Blood Plasma | - | - | 86% (accuracy) | [33] |

| Endometrial Cancer | ATR-FTIR (dry plasma) | Blood Plasma | - | - | 83% (accuracy) | [33] |

| Breast Cancer (Lymph nodes) | Raman Spectroscopy | Tissue | 92% | 100% | - | [28] |

The Exosome-SERS-AI approach for simultaneous detection of six cancer types (lung, breast, colon, liver, pancreas, and stomach) represents a particularly significant advancement. This method achieved an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.970 for detecting cancer presence and a mean AUC of 0.945 for classifying the tissue of origin in early-stage cancer patients. The integrated decision model showed a sensitivity of 90.2% at a specificity of 94.4%, while correctly predicting the tumor organ for 72% of positive patients. This performance is notable for a single test capable of detecting multiple cancer types simultaneously, highlighting the potential of SERS-based liquid biopsy for multi-cancer early detection [32].

For endometrial cancer detection, Raman spectroscopy of 'wet' blood plasma samples achieved 82% diagnostic accuracy, outperforming ATR-FTIR spectroscopy applied to the same sample type (78% accuracy). Notably, the combination of both spectroscopic techniques synergistically improved diagnostic accuracy to 86%, demonstrating the complementary nature of these approaches. Interestingly, ATR-FTIR performed better with dried plasma samples (83% accuracy) than with 'wet' plasma, reflecting the technique's sensitivity to water interference [33].

In breast cancer diagnostics, Raman spectroscopy demonstrated exceptional performance for intraoperative lymph node assessment, with 92% sensitivity and 100% specificity for detecting metastasis. This performance surpasses conventional intraoperative methods like touch imprint cytology and frozen section microscopy, which typically have poorer sensitivity and require experienced pathologists for interpretation. The Raman-based approach could potentially reduce the need for secondary surgeries by enabling complete lymph node removal during the initial procedure if malignancy is detected [28].

Technical Comparison of Vibrational Spectroscopy Techniques

Table 3: Technical Comparison of Spectroscopy Techniques for Biomedical Analysis

| Parameter | Raman Spectroscopy | SERS | FTIR Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Detection Limit | μM-mM range | Single molecule potential | nM-μM range |

| Measurement Time | Seconds to minutes | Seconds | Seconds to minutes |

| Multiplexing Capacity | Moderate | High (narrow bands) | Limited (broad bands) |

| Fluorescence Interference | Potentially high | Quenched | Minimal |

| Reproducibility | High | Moderate (substrate-dependent) | High |

| Clinical Translation Stage | Research and early clinical | Advanced research | Research |

| Key Applications in Oncology | Tissue diagnosis, intraoperative guidance | Liquid biopsy, biomarker detection | Tissue analysis, biofluid screening |

Raman spectroscopy offers several practical advantages for clinical applications. Its compatibility with aqueous environments enables analysis of biological samples with minimal preparation, and the ability to fiber-optically deliver laser light facilitates integration with endoscopic and needle-based platforms for in vivo measurements. The non-destructive nature permits subsequent analysis of the same sample by other techniques, an important consideration for precious clinical specimens [27] [7].

The main limitations of conventional Raman spectroscopy include relatively weak signals and long acquisition times, which have largely been addressed by technological advancements. SERS dramatically improves sensitivity but introduces substrate-dependent variability and requires additional sample preparation steps. The complexity of biological spectra also necessitates sophisticated multivariate analysis tools for proper interpretation [30] [31].

FTIR spectroscopy remains a valuable complementary technique, particularly for high-throughput screening applications where its faster acquisition times and lower instrumentation costs provide practical advantages. However, its strong water absorption and poorer spatial resolution limit its utility for many in vivo and single-cell applications where Raman excels [1] [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of Raman-based cancer diagnostics requires carefully selected materials and reagents optimized for spectroscopic analysis:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for SERS-Based Exosome Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Specific Examples | Performance Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| SERS Substrate | Signal enhancement through plasmonic resonance | Gold nanoparticle-aggregated arrays, Klarite substrates | Enhancement factors of 10^6-10^8; uniformity critical for reproducibility |

| Exosome Isolation Kits | Purification of exosomes from biofluids | Size exclusion chromatography columns, polymer-based precipitation kits | SEC preferred for SERS to avoid chemical contaminants; purity verified via Western blot |

| Plasma Collection Tubes | Sample collection and preservation | EDTA or citrate blood collection tubes | Prevents coagulation; maintains exosome integrity |

| Reference Standards | Instrument calibration and quality control | Rhodamine 6G, 4-mercaptobenzoic acid | Verifies substrate enhancement factor and instrument performance |

| Cell Culture Reagents | In vitro model systems | Cell lines, exosome-depleted FBS, characterizaton antibodies | Enables controlled experiments with known exosome sources |

| Data Analysis Software | Spectral processing and multivariate analysis | Python with scikit-learn, SIMCA, MATLAB | Machine learning algorithms essential for spectral classification |

The selection of SERS substrates represents a particularly critical consideration. Gold nanoparticles typically provide better biocompatibility and more stable surfaces compared to silver, though silver often delivers higher enhancement factors. Substrate reproducibility remains a challenge in SERS, with commercial substrates like Klarite offering improved uniformity compared to laboratory-fabricated alternatives. For exosome analysis, substrates must be optimized for the size range of extracellular vesicles (30-150 nm) to ensure efficient adsorption and enhancement [32] [30] [31].

Exosome isolation methodology significantly impacts downstream SERS analysis. Size exclusion chromatography is generally preferred over polymer-based precipitation methods for SERS applications because it avoids chemical contaminants that could produce interfering Raman signals. The purity of exosome preparations should be validated through multiple orthogonal techniques, including nanoparticle tracking analysis for size distribution, Western blot for marker expression (CD9, CD63, CD81), and electron microscopy for morphological assessment [32].

Raman spectroscopy has established itself as a powerful analytical technique with transformative potential in cancer diagnostics. The method's label-free nature, molecular specificity, and compatibility with aqueous samples position it ideally for both tissue-based diagnosis and liquid biopsy applications. The exceptional performance of SERS-based exosome analysis for multi-cancer detection, achieving AUC values exceeding 0.94 for identifying both cancer presence and tissue of origin, demonstrates the clinical viability of this approach [32].

The complementary relationship between Raman and IR spectroscopy enables more comprehensive molecular characterization when combined, as evidenced by the synergistic improvement in endometrial cancer detection accuracy from 82% (Raman alone) to 86% (combined approach) [33]. Future diagnostic platforms may increasingly leverage both techniques to maximize diagnostic accuracy.

Technical advancements continue to address initial limitations of Raman spectroscopy. Portable, cost-effective systems with improved sensitivity are facilitating clinical translation, while standardized substrate manufacturing processes are enhancing reproducibility. The integration of artificial intelligence for spectral analysis is perhaps the most significant development, enabling robust classification based on complex, multi-component spectral patterns rather than individual biomarker quantification [27] [32].

As these technologies mature, Raman-based approaches are poised to address critical unmet needs in oncology, including early detection of elusive cancers, real-time surgical guidance, and minimally invasive therapy monitoring. The ongoing transition from research laboratories to clinical settings heralds a new era of spectroscopic medicine, where molecular fingerprinting provides immediate, actionable diagnostic information to improve cancer outcomes.

Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy has emerged as a cornerstone technique in life sciences for probing the structure and dynamics of biomolecules. This analytical method measures how molecules absorb infrared light, creating a unique "molecular fingerprint" based on the vibrational modes of chemical bonds [34]. In the context of protein analysis, FT-IR spectroscopy provides unparalleled insights into secondary structure elements, conformational changes, and biomolecular interactions that are fundamental to understanding biological function and facilitating drug development [35] [36]. The technique's sensitivity to subtle molecular alterations, combined with its non-destructive nature and minimal sample preparation requirements, has established it as an indispensable tool in research laboratories worldwide [34] [36].

When compared to complementary techniques like Raman spectroscopy, FT-IR occupies a specific niche with distinct advantages and limitations. While Raman spectroscopy depends on a change in molecular polarizability and is particularly sensitive to homo-nuclear molecular bonds (e.g., C-C, C=C), FT-IR spectroscopy depends on a change in dipole moment and excels at detecting hetero-nuclear functional group vibrations and polar bonds [12]. This fundamental difference makes FT-IR especially powerful for analyzing aqueous biological systems and characterizing the secondary structure of proteins through their amide vibrations [37] [38]. The ongoing technological advancements in FT-IR instrumentation, including enhanced imaging capabilities and high-throughput microarray systems, continue to expand its applications in pharmaceutical development and clinical diagnostics [36] [39].

Fundamental Principles of FT-IR for Protein Analysis

Key Spectral Regions for Biomolecular Characterization

FT-IR spectroscopy characterizes molecules based on how they absorb infrared light, typically in the mid-IR range (4,000–400 cm⁻¹) [40]. The resulting spectrum provides a vibrational fingerprint of the sample, with absorption peaks corresponding to specific functional groups and molecular bonds. For biological samples, several key spectral regions provide critical structural information, with the amide I and II bands being particularly valuable for protein secondary structure determination [37] [34].

Table 1: Key FT-IR Spectral Regions for Biomolecular Analysis

| Spectral Region (cm⁻¹) | Vibrational Mode | Biomolecular Information |

|---|---|---|

| 3700-2700 | O-H, N-H, C-H stretching | Protein amide A, lipid CH₂, CH₃ groups, carbohydrate O-H |

| ~3300 | N-H stretching | Amide A band of proteins |

| 3010 | =C-H stretching | Unsaturated lipids (olefinic band) |

| 2957-2852 | C-H stretching | Saturated lipids (CH₂, CH₃ antisymmetric/symmetric stretches) |

| 1740 | C=O stretching | Ester carbonyl groups in lipids |

| 1700-1600 | C=O stretching, C-N bending | Amide I band (protein secondary structure) |

| 1590-1490 | N-H bending, C-N stretching | Amide II band (protein secondary structure) |

| 1500-800 | Various molecular vibrations | "Fingerprint region" for complex biomolecular analysis |

The amide I band (approximately 1700-1600 cm⁻¹), resulting from C=O stretching (80%) and C-N stretching vibrations, is particularly sensitive to protein secondary structure [37] [38]. The exact absorption frequency within this range varies according to specific structural elements: α-helices typically absorb at 1650-1658 cm⁻¹, β-sheets at 1620-1640 cm⁻¹, and disordered structures at 1640-1650 cm⁻¹ [37]. The amide II band (1590-1490 cm⁻¹), primarily deriving from N-H bending and C-N stretching vibrations, provides complementary structural information [37].

Comparison of FT-IR with Raman Spectroscopy

FT-IR and Raman spectroscopy provide complementary approaches to vibrational analysis, with fundamental differences in their physical basis and applications.

Table 2: FT-IR versus Raman Spectroscopy for Biomolecular Analysis

| Parameter | FT-IR Spectroscopy | Raman Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Basis | Measures absorption of IR light due to change in dipole moment | Measures inelastic scattering of light due to change in polarizability |

| Sensitivity | Hetero-nuclear functional groups, polar bonds (especially O-H in water) | Homo-nuclear molecular bonds (C-C, C=C, C≡C) |

| Sample Preparation | Constraints on sample thickness, uniformity, and dilution to avoid saturation | Little to no sample preparation required |

| Interference | Not affected by fluorescence | Fluorescence may interfere with measurements |

| Water Compatibility | Strong water absorption can interfere with measurements | Minimal interference from water |

| Protein Structure | Excellent for secondary structure via amide I and II bands | Provides complementary information on protein conformation |

The choice between these techniques depends on the specific analytical requirements. FT-IR is particularly advantageous for studying hydrated biological samples and determining protein secondary structure, while Raman spectroscopy excels in samples where water interference is problematic and when information about symmetric covalent bonds is needed [12].

Experimental Approaches for Protein Secondary Structure Analysis

Sample Preparation Methodologies

Proper sample preparation is critical for obtaining high-quality FT-IR spectra. Biological samples for FT-IR analysis can be prepared in several ways, with the choice of method depending on the sample type and experimental objectives [34]:

Transmission Mode: The most straightforward approach where IR radiation passes directly through the sample. Proteins in solution are typically placed between two infrared-transparent windows (e.g., BaF₂) separated by a thin spacer. This method requires careful control of sample thickness and buffer composition to avoid signal saturation [37] [34].

Attenuated Total Reflection (ATR): A widely used technique where the sample is placed in contact with a high-refractive-index crystal (e.g., diamond, ZnSe, or Ge). The infrared beam undergoes total internal reflection within the crystal, generating an evanescent wave that penetrates the sample. ATR requires minimal sample preparation and is ideal for solid proteins, gels, and viscous solutions [34] [40]. Recent advancements include multi-bounce ATR accessories that enhance signal-to-noise ratio for low-concentration samples [40].

Transflection Mode: Combines transmission and reflection principles, where IR radiation passes through the sample, reflects off a substrate, and passes through the sample again. This approach provides higher absorbance signals but requires reflective substrates [34].

For protein secondary structure analysis, samples must be properly concentrated (typically 1-10 mg/mL for transmission measurements) and in compatible buffers that minimize strong infrared absorptions. Phosphate buffers should generally be avoided in favor of Hepes or similar buffers with lower infrared absorption [37]. Water absorption can be mitigated by using deuterated buffers or carefully matching reference and sample buffers.

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for FT-IR protein secondary structure analysis

Hydrogen/Deuterium Exchange for Enhanced Resolution

Hydrogen/deuterium exchange (HDX) represents a powerful strategy to enhance the resolution of overlapping amide I bands in FT-IR spectroscopy [37]. This method exploits the differential exchange rates of amide hydrogens for deuterium in various secondary structure elements:

- Rapid Exchange: Disordered structures and solvent-exposed regions exchange rapidly (seconds to minutes)

- Slow Exchange: Structured elements like α-helices and β-sheets exchange more slowly due to hydrogen bonding and limited solvent accessibility

Upon deuteration, the amide I band shifts to lower wavenumbers by approximately 5-10 cm⁻¹ for partially deuterated samples and up to 12 cm⁻¹ for fully deuterated proteins [37]. This differential shifting helps separate the overlapping absorption bands of disordered structures and α-helices that normally absorb at similar frequencies. A 2021 study demonstrated that prediction errors for α-helix content were significantly reduced after 15 minutes of deuteration, while β-sheet content was better predicted in non-deuterated conditions [37].

The experimental protocol for HDX-FTIR typically involves:

- Preparing protein samples in H₂O-based buffer

- Exchanging into D₂O-based buffer via filtration or size exclusion chromatography

- Incubating for specific timepoints (e.g., 15 minutes, 1 hour, 24 hours)

- Collecting spectra at each timepoint while minimizing back-exchange

- Analyzing spectral changes in the amide I and amide II regions

High-Throughput Approaches with Protein Microarrays

Recent advancements have enabled high-throughput FT-IR analysis through the combination of protein microarrays and infrared imaging [37]. This approach involves:

- Printing nanoliter volumes of protein solutions (100 pL drops) onto infrared-transparent substrates (e.g., BaF₂) using non-contact inkjet microarrayers

- Creating arrays with spot-to-spot distances of 200 μm, allowing approximately 2,000 protein samples per cm²

- Using focal plane array (FPA) detectors to simultaneously collect spectra from multiple array spots

- Applying partial least squares (PLS) regression, support vector machine (SVM), or ascending stepwise linear regression (ASLR) for spectral analysis and structure prediction

This methodology has been successfully applied to a library of 85 soluble proteins, demonstrating FT-IR's capability for rapid secondary structure assessment across diverse protein families [37].

Research Reagent Solutions for FT-IR Protein Analysis

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for FT-IR Protein Studies

| Item | Function/Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Infrared-Transparent Windows | Sample substrate for transmission measurements | BaF₂, CaF₂, ZnSe windows [37] |

| ATR Crystals | Internal reflection element for ATR measurements | Diamond, Ge, ZnSe crystals [34] [40] |

| Deuterated Buffers | Hydrogen/deuterium exchange studies | D₂O-based buffers for HDX-FTIR [37] |

| Size Exclusion Spin Columns | Buffer exchange and desalting | Bio-Rad Micro Bio-Spin columns, Amicon centrifugal filters [37] |

| Protein Microarray Systems | High-throughput FT-IR analysis | Arrayjet Marathon non-contact inkjet microarrayer [37] |

| Chemometric Software | Spectral processing and multivariate analysis | PCA, PLS, SVM, ASLR algorithms [37] [36] |

Quantitative Analysis of Protein Secondary Structure

Prediction Accuracy Across Structural Elements

FT-IR spectroscopy, particularly when combined with advanced computational approaches, provides quantitative assessment of protein secondary structure content. A comprehensive 2021 study evaluating 85 proteins revealed distinct prediction accuracies for different structural elements under various experimental conditions [37]:

- β-Sheet Structures: Consistently show the best prediction accuracy, particularly in non-deuterated conditions with errors typically below 5-7%

- α-Helical Structures: Prediction improves significantly after 15 minutes of hydrogen/deuterium exchange, with error reduction of approximately 20-30% compared to non-deuterated measurements

- Disordered Structures and Turns: Categorized as "Others," these elements show improved prediction following partial deuteration, likely due to differential exchange rates

The prediction models typically employ partial least squares (PLS) regression, which effectively handles the multicollinearity in FT-IR spectral data. Cross-validation and independent test sets (e.g., 25-protein validation sets) confirm the robustness of these quantitative approaches [37].

Comparative Performance Data

Figure 2: FT-IR data analysis workflow for protein characterization

Table 4: Quantitative Performance of FT-IR for Secondary Structure Prediction

| Secondary Structure Type | Optimal Measurement Condition | Prediction Error Range | Key Spectral Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| β-Sheet | Non-deuterated | Lower error compared to α-helix | 1620-1640 cm⁻¹ (inter-chain), 1670-1695 cm⁻¹ (intra-chain) |

| α-Helix | 15-minute deuteration | Error reduced by 20-30% after HDX | 1650-1658 cm⁻¹, shifts to 1645-1655 cm⁻¹ upon deuteration |

| Disordered Structures | 15-minute deuteration | Improved after HDX | 1640-1650 cm⁻¹, shifts markedly to lower wavenumbers upon deuteration |

| Turns and Bends | Partially deuterated | Moderate prediction accuracy | 1660-1700 cm⁻¹, variable upon deuteration |

The prediction accuracy is influenced by several factors, including spectral quality, protein concentration, and the reference method used for validation (typically X-ray crystallography or NMR spectroscopy). For most applications, FT-IR can determine secondary structure content with absolute errors of 3-8% when appropriate experimental and computational approaches are employed [37].

Applications in Pharmaceutical Development and Biomedical Research

Biopharmaceutical Characterization

FT-IR spectroscopy has become an essential tool in biopharmaceutical development, particularly for therapeutic proteins where secondary structure directly impacts stability and efficacy [37] [39]. Key applications include:

- Formulation Development: Monitoring protein structural integrity in various excipient formulations to identify optimal storage conditions [39] [40]