Optimizing Text Sample Size for Forensic Comparison: A Data-Driven Framework for Reliable Evidence

This article provides a comprehensive framework for determining optimal text sample sizes in forensic text comparison (FTC), addressing a critical need for validated, quantitative methods in forensic linguistics.

Optimizing Text Sample Size for Forensic Comparison: A Data-Driven Framework for Reliable Evidence

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for determining optimal text sample sizes in forensic text comparison (FTC), addressing a critical need for validated, quantitative methods in forensic linguistics. We explore the foundational relationship between sample size and discrimination accuracy, detailing methodological approaches within the Likelihood Ratio framework. The content systematically addresses troubleshooting common challenges like topic mismatch and data scarcity and underscores the necessity of empirical validation using forensically relevant data. Aimed at researchers, forensic scientists, and legal professionals, this review synthesizes current research to guide the development of scientifically defensible and demonstrably reliable FTC practices, ultimately strengthening the integrity of textual evidence in legal proceedings.

The Science of Sample Size: Core Principles of Forensic Text Comparison

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the core challenge of sample size in forensic text comparison? The sample size problem refers to the difficulty in obtaining sufficient known writing samples from a suspect that are both reliable and relevant to the case. A small or stylistically inconsistent known sample can lead to unreliable results, as the statistical models have insufficient data to characterize the author's unique writing style accurately [1].

How does sample size impact the accuracy of an analysis? Larger sample sizes generally lead to more reliable results. Machine Learning (ML) models, in particular, require substantial data for training to identify subtle, author-specific patterns effectively. Research indicates that ML algorithms can outperform manual methods, with one review noting a 34% increase in authorship attribution accuracy for ML models [2]. However, an inappropriately small sample can cause both manual and computational methods to miss or misrepresent the author's consistent style.

What constitutes a "relevant" known writing sample? A relevant sample matches the conditions of the case under investigation [1]. This means the known writings should be similar in topic, genre, formality, and context to the questioned document. Using known texts that differ significantly in topic from the questioned text (a "topic mismatch") is a major challenge and can invalidate an analysis if not properly accounted for during validation [1].

Can I use computational methods if I only have a small text sample? While computational methods like deep learning excel with large datasets, a small sample size severely limits their effectiveness. In such cases, manual analysis by a trained linguist may be superior for interpreting cultural nuances and contextual subtleties [2]. A hybrid approach, which uses computational tools to process data but relies on human expertise for final interpretation, is often recommended when data is limited [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconclusive or Weak Results from Software

Symptoms: Your authorship attribution software returns low probability scores, high error rates, or results that are easily challenged.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause: Insufficient Known Text

- Solution: Expand the collection of known writings from the suspect. Prioritize finding documents that are contemporaneous with the questioned document and similar in genre (e.g., formal emails, casual text messages).

Cause: Topic Mismatch

- Solution: This is a common problem. The validation of your method must account for this. Ensure your experimental design and reference data include cross-topic comparisons to test the robustness of your analysis [1].

Cause: Inadequate Model Validation

- Solution: Any system or methodology must be empirically validated using data and conditions that reflect the specific case. Do not rely on a generic, one-size-fits-all model. Follow the two main requirements for validation: (1) reflect the case conditions, and (2) use relevant data [1].

Problem: Defending Your Methodology in Court

Symptoms: Challenges to the scientific basis, admissibility, or potential bias of your analysis.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause: Lack of Empirical Validation

- Solution: Be prepared to demonstrate that your method was validated under conditions mimicking the case. This includes using relevant data and testing for known confounding factors like topic mismatch [1].

Cause: Algorithmic Bias

- Solution: Acknowledge and test for biases in your training data and algorithms. Use transparent models where possible and be ready to explain the limitations of your system. The field is advocating for standardized validation protocols and ethical safeguards to address this [2].

Cause: Not Using the Likelihood-Ratio (LR) Framework

- Solution: The LR framework is increasingly seen as the legally and logically correct approach for evaluating forensic evidence. It quantifies the strength of evidence by comparing the probability of the evidence under the prosecution and defense hypotheses [1]. Transitioning to this framework enhances the transparency and scientific defensibility of your findings.

The following tables summarize key quantitative findings and guidelines relevant to forensic text comparison.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Analysis Methods

| Method | Key Strength | Key Weakness | Impact of Small Sample Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manual Analysis | Superior at interpreting cultural nuances and contextual subtleties [2]. | Susceptible to cognitive bias; lacks scalability; difficult to validate [2] [1]. | High; relies heavily on expert intuition, which can be misled by limited data. |

| Machine Learning (ML) | Can process large datasets rapidly; identifies subtle linguistic patterns (34% increase in authorship attribution accuracy cited) [2]. | Requires large datasets; can be a "black box"; risk of algorithmic bias if training data is flawed [2]. | Very High; models may fail to train or generalize properly, leading to inaccurate results. |

| Hybrid Framework | Merges computational scalability with human expertise for interpretation [2]. | More complex to implement and validate. | Medium; human expert can override or contextualize unreliable computational outputs. |

Table 2: Core Requirements for Empirical Validation

| Requirement | Description | Application to Sample Size |

|---|---|---|

| Reflect Case Conditions | The validation experiment must replicate the specific conditions of the case under investigation (e.g., topic mismatch, genre) [1]. | The known samples used for validation must be of a comparable size and type to what is available in the actual case. |

| Use Relevant Data | The data used for validation must be relevant to the case. Using general, mismatched data can mislead the trier-of-fact [1]. | Ensures that the model is tested on data that reflects the actual sample size and stylistic variation it will encounter. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Validating for Topic Mismatch

Objective: To ensure your authorship verification method is robust when the known and questioned documents differ in topic.

- Data Curation: Collect a dataset of texts from multiple authors. For each author, ensure you have writings on at least two distinct topics.

- Define Conditions: For the validation experiment, designate one topic as the "known" sample and the other as the "questioned" sample. This simulates the topic mismatch condition.

- Run Comparison: Calculate Likelihood Ratios (LRs) using your chosen statistical model (e.g., a Dirichlet-multinomial model followed by logistic-regression calibration) [1].

- Performance Assessment: Evaluate the derived LRs using metrics like the log-likelihood-ratio cost and visualize them with Tippett plots [1]. Compare the performance against a baseline where topics match.

Protocol 2: Implementing the Likelihood-Ratio Framework

Objective: To quantitatively evaluate the strength of textual evidence.

- Formulate Hypotheses:

- Prosecution Hypothesis (Hp): The suspect is the author of the questioned document.

- Defense Hypothesis (Hd): The suspect is not the author (another person from a relevant population wrote it).

- Extract Features: Quantitatively measure stylistic features (e.g., word frequencies, syntactic patterns) from both the questioned document and the known documents of the suspect.

- Calculate Probabilities:

- Compute

p(E|Hp): The probability of observing the evidence (the stylistic features) if the suspect is the author. - Compute

p(E|Hd): The probability of observing the evidence if someone else is the author.

- Compute

- Compute LR: The Likelihood Ratio is

LR = p(E|Hp) / p(E|Hd)[1]. An LR > 1 supports Hp, while an LR < 1 supports Hd. The further from 1, the stronger the evidence.

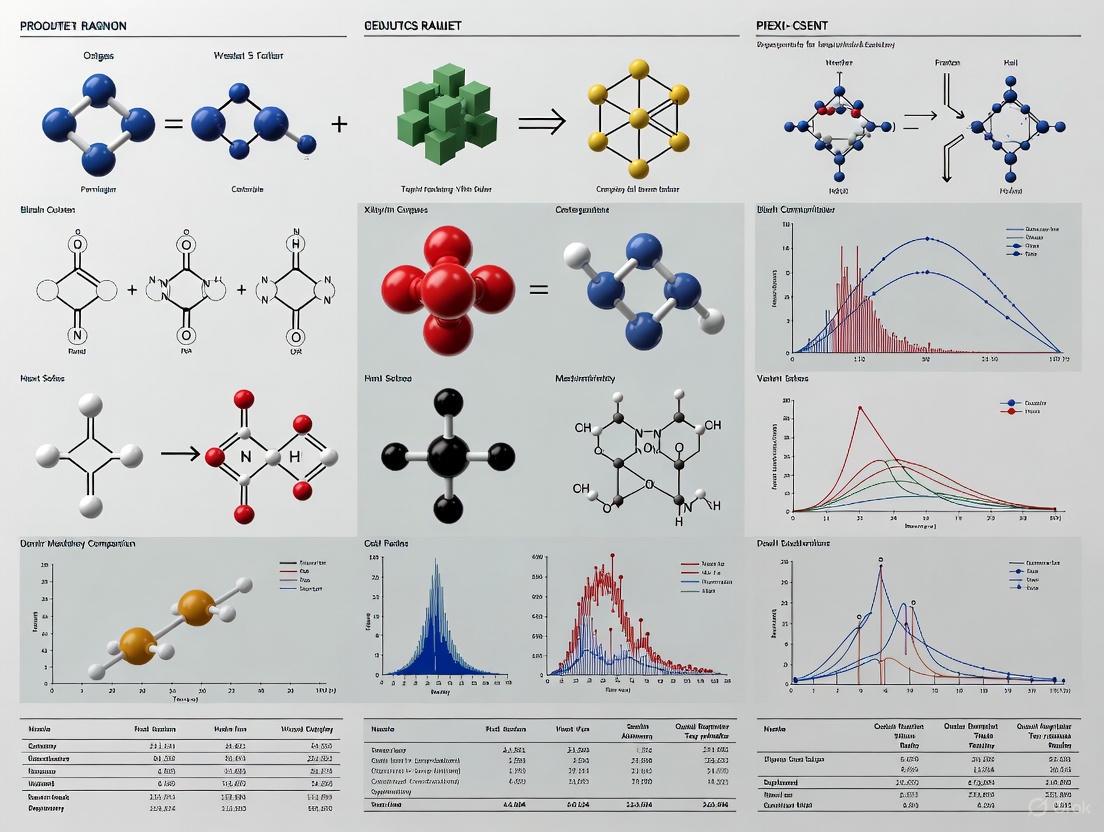

Methodology Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Forensic Text Comparison

| Item / Solution | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Reference Text Corpus | A large, structured collection of texts from many authors. Serves as a population model to estimate the typicality of writing features under the defense hypothesis (Hd) [1]. |

| Computational Stylometry Software | Software that quantitatively analyzes writing style (e.g., frequency of function words, character n-grams). Used for feature extraction and as the engine for machine learning models [2]. |

| Likelihood-Ratio (LR) Framework | The statistical methodology for evaluating evidence. It provides a transparent and logically sound way to quantify the strength of textual evidence by comparing two competing hypotheses [1]. |

| Validation Dataset with Topic Mismatches | A specialized dataset containing writings from the same authors on different topics. Critical for empirically testing and validating the robustness of your method against a common real-world challenge [1]. |

| Hybrid Analysis Protocol | A formalized methodology that integrates the output of computational models with the interpretive expertise of a trained linguist. This is a key solution for mitigating the limitations of either approach used alone [2]. |

Theoretical Foundation & Key Concepts

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is an idiolect and why is it relevant for forensic authorship analysis? An idiolect is an individual's unique and distinctive use of language, encompassing their specific patterns of vocabulary, grammar, and pronunciation [3]. In forensic text comparison, the concept is crucial because every author possesses their own 'idiolect'—a distinctive, individuating way of writing [1]. This unique linguistic "fingerprint" provides the theoretical basis for determining whether a questioned document originates from a specific individual.

Q2: What is the "rectilinearity hypothesis" in the context of idiolect? The rectilinearity hypothesis proposes that certain aspects of an author's writing style evolve in a rectilinear, or monotonic, manner over their lifetime [4]. This means that with appropriate methods and stylistic markers, these chronological changes are detectable and can be modeled. Quantitative studies on 19th-century French authors support this, showing that the evolution of an idiolect is, in a mathematical sense, monotonic for most writers [4].

Q3: What is the role of the Likelihood Ratio (LR) in evaluating authorship evidence? The Likelihood Ratio (LR) is the logically and legally correct framework for evaluating forensic evidence, including textual evidence [5] [1]. It is a quantitative statement of the strength of evidence, calculated as the probability of the evidence (e.g., the text) assuming the prosecution hypothesis (Hp: the suspect is the author) is true, divided by the probability of the same evidence assuming the defense hypothesis (Hd: someone else is the author) is true [1]. An LR >1 supports Hp, while an LR <1 supports Hd.

Q4: Why is topic mismatch between texts a significant challenge in analysis? A text encodes complex information, including not just author identity but also group-level information and situational factors like genre, topic, and formality [1]. Mismatched topics between a questioned document and known reference samples are particularly challenging because an individual's writing style can vary depending on the communicative situation [1]. This can confound stylistic analysis if not properly accounted for in validation experiments.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Frequently Asked Questions

Q5: My authorship analysis results are inconsistent. Could text sample size be the cause? Yes, sample size is a critical factor. Research demonstrates that the performance of a forensic text comparison system is directly impacted by the amount of text available [5]. The scarcity of data is a common challenge in real casework. Studies show that employing logistic-regression fusion of results from multiple analytical procedures is particularly beneficial for improving the reliability and discriminability of results when sample sizes are small (e.g., 500–1500 tokens) [5].

Q6: Which linguistic features are most effective for characterizing an idiolect? No single set of features has been universally agreed upon [6]. However, successful approaches often use a combination of feature types. Core categories include:

- Lexico-morphosyntactic patterns (motifs): These are patterns involving grammar and style that have been shown to effectively trace idiolectal evolution [4].

- Function words and high-frequency words: These are core aspects of language, and their usage has been found to be highly recognizable and stable for an individual [4].

- Character N-grams: These sequences of characters are effective as they capture idiosyncratic habits in spelling, morphology, and word formation [5].

- Vocabulary richness and sentence length: These are traditional markers in stylometry, though their stability can vary [6].

Q7: How can I validate my forensic text comparison methodology? Empirical validation is essential. According to standards in forensic science, validation must be performed by [1]:

- Reflecting the conditions of the case under investigation (e.g., replicating potential topic mismatches).

- Using data relevant to the case (e.g., using texts from a similar genre, register, and time period as the questioned document). Failing to meet these requirements may mislead the trier-of-fact and produce unreliable results.

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Assessing Chronological Signal and Idiolect Evolution

This protocol is designed to test the rectilinearity hypothesis and determine if an author's style changes monotonically over time [4].

- Corpus Compilation (CIDRE Method): Gather a diachronic corpus of an author's works, each with a reliable publication date. This serves as the gold standard for evaluation [4].

- Feature Extraction: Extract lexico-morphosyntactic patterns (

motifs) from each text in the corpus. - Distance Matrix Calculation: Calculate a distance matrix between all pairs of texts based on the extracted stylistic features.

- Chronological Signal Test: Develop a method to calculate if the distance matrix contains a stronger chronological signal than expected by chance. A stronger-than-chance signal supports the rectilinearity hypothesis [4].

- Regression Modeling: Build a linear regression model to predict the publication year of a work based on its stylistic features. A high model accuracy and explained variance further support rectilinear evolution [4].

- Feature Inspection: Apply a feature selection algorithm to identify the specific motifs that play the greatest role in the chronological evolution for qualitative analysis [4].

Workflow for Analyzing Idiolect Evolution

Protocol 2: A Likelihood Ratio Framework for Forensic Text Comparison

This protocol outlines a fused system for calculating the strength of textual evidence within the LR framework [5].

- Data Preparation: Compile known writings from a suspect (K) and an anonymous questioned document (Q). Convert texts to a machine-readable format.

- Multi-Procedure Feature Extraction: Analyze the texts using three distinct procedures in parallel:

- MVKD Procedure: Model texts using multivariate authorship attribution features (e.g., vocabulary richness, average sentence length, uppercase character ratio) [5].

- Token N-grams Procedure: Model texts using sequences of words (e.g., bigrams, trigrams).

- Character N-grams Procedure: Model texts using sequences of characters.

- Likelihood Ratio Estimation: For each procedure, estimate a separate LR using the respective model.

LR = p(E|Hp) / p(E|Hd)- Where

Hpis "K and Q were written by the same author," andHdis "K and Q were written by different authors" [1].

- Logistic-Regression Fusion: Fuse the LRs from the three procedures into a single, more robust LR using logistic-regression calibration [5].

- System Performance Assessment: Evaluate the quality and discriminability of the fused LRs using metrics like the log-likelihood ratio cost (Cllr) and Tippett plots [5].

Fused Forensic Text Comparison System

Reference Tables for Experimental Design

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Idiolect Analysis

| Research Reagent | Function & Explanation |

|---|---|

| Diachronic Corpora (CIDRE) | A corpus containing the dated works of prolific authors. Serves as the essential "gold standard" for training and testing models of idiolectal evolution over a lifetime [4]. |

| Lexico-Morphosyntactic Motifs | Pre-defined grammatical-stylistic patterns that function as detectable "biomarkers" of an author's unique style. They are the key features for identifying and quantifying stylistic change [4]. |

| Multivariate Kernel Density (MVKD) Model | A statistical model that treats a set of messages or texts as a vector of multiple authorship features. It is used to estimate the probability of observing the evidence under competing hypotheses [5]. |

| N-gram Models (Token & Character) | Models that capture an author's habitual use of word sequences (token n-grams) and character sequences (character n-grams). These are highly effective for capturing subconscious stylistic patterns [5]. |

| Logistic-Regression Calibration | A robust computational procedure that converts raw similarity scores into well-calibrated Likelihood Ratios (LRs). It also allows for the fusion of LRs from different analysis procedures into a single, more reliable value [5]. |

Table 2: Impact of Text Sample Size on System Performance

This table summarizes simulated experimental data on the impact of token sample size on the performance of a fused forensic text comparison system, as measured by the log-likelihood ratio cost (Cllr). Lower Cllr values indicate better system performance [5].

| Sample Size (Tokens) | Cllr (Fused System) | Cllr (MVKD only) | Cllr (Token N-grams only) | Cllr (Character N-grams only) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 500 | 0.503 | 0.732 | 0.629 | 0.576 |

| 1000 | 0.422 | 0.629 | 0.503 | 0.455 |

| 1500 | 0.378 | 0.576 | 0.455 | 0.403 |

| 2500 | 0.332 | 0.503 | 0.403 | 0.357 |

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Experimental Issues and Solutions

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common Likelihood Ratio Framework Challenges

| Problem Scenario | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| LR value is close to 1, providing no diagnostic utility [7]. | The chosen model or feature does not effectively discriminate between the hypotheses. | Refine the model parameters or select different, more discriminative features for comparison. |

| Violation of nested model assumption during Likelihood-Ratio Test (LRT) [8] [9]. | The complex model is not a simple extension of the simpler model (i.e., models are not hierarchically nested). | Ensure the simpler model is a special case of the complex model, achievable by constraining one or more parameters [9]. |

| Uncertainty in the computed LR value, raising questions about its reliability [10]. | Sampling variability, measurement errors, or subjective choices in model assumptions. | Perform an extensive uncertainty analysis, such as using an assumptions lattice and uncertainty pyramid framework to explore a range of reasonable LR values [10]. |

| Inability to interpret the magnitude of an LR in a practical context. | Lack of empirical meaning for the LR quantity. | Use the LR in conjunction with a pre-test probability and a tool like the Fagan nomogram to determine the post-test probability [7]. |

| LRT statistic does not follow a chi-square distribution, leading to invalid p-values. | Insufficient sample size for the asymptotic approximation to hold [8]. | Increase the sample size or investigate alternative testing methods that do not rely on large-sample approximations. |

FAQs on the Likelihood Ratio Framework

Q1: What is the core function of a Likelihood Ratio (LR)? The LR quantifies how much more likely the observed evidence is under one hypothesis (e.g., the prosecution's proposition) compared to an alternative hypothesis (e.g., the defense's proposition) [10]. It is a metric for updating belief about a hypothesis in the face of new evidence.

Q2: Why must models be "nested" to use a Likelihood-Ratio Test (LRT)? The LRT compares a simpler model (null) to a more complex model (alternative). For the test to be valid, the simpler model must be a special case of the complex model, obtainable by restricting some of its parameters. This ensures the comparison is fair and that the test statistic follows a known distribution under the null hypothesis [8] [9].

Q3: Can LRs from different tests or findings be multiplied together sequentially? While it may seem mathematically intuitive, LRs have not been formally validated for use in series or in parallel [7]. Applying one LR after another assumes conditional independence of the evidence, which is often difficult to prove in practice and can lead to overconfident or inaccurate conclusions.

Q4: What is the critical threshold for a useful LR? An LR of 1 has no diagnostic value, as it does not change the prior probability [7]. The further an LR is from 1 (e.g., >>1 for strong evidence for a proposition, or <<1 for strong evidence against it), the more useful it is for shifting belief. The specific thresholds for "moderate" or "strong" evidence can vary by field.

Q5: How does the pre-test probability relate to the LR? The pre-test probability (or prior odds) is the initial estimate of the probability of the hypothesis before considering the new evidence. The LR is the multiplier that updates this prior belief to a post-test probability (posterior odds) via Bayes' Theorem [7]. The same LR will have a different impact on a low vs. a high pre-test probability.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Core Workflow for Evidence Evaluation using the LR Framework

The following diagram illustrates the logical process for applying the Likelihood Ratio Framework to evaluate evidence, from hypothesis formulation to final interpretation.

Protocol: Executing a Likelihood-Ratio Test (LRT) for Nested Models

This protocol is used for comparing the goodness-of-fit of two statistical models, such as in phylogenetics or model selection [9].

Objective: To determine if a more complex model (Model 1) fits a dataset significantly better than a simpler, nested model (Model 0).

Procedure:

- Model Fitting:

- Fit Model 0 (the simpler, null model) to the dataset and obtain its maximum log-likelihood value (lnL₀).

- Fit Model 1 (the more complex, alternative model) to the same dataset and obtain its maximum log-likelihood value (lnL₁).

Calculate Test Statistic:

- Compute the likelihood ratio test statistic (LR) using the formula: LR = 2 * (lnL₁ - lnL₀) [9].

Determine Degrees of Freedom (df):

- Calculate the degrees of freedom for the test. This is equal to the difference in the number of free parameters between Model 1 and Model 0 [9].

Significance Testing:

- Compare the calculated LR statistic to the critical value from a chi-square (χ²) distribution with the determined degrees of freedom.

- If the LR statistic exceeds the critical value, the more complex model (Model 1) provides a significantly better fit to the data than the simpler model (Model 0).

Workflow for Likelihood-Ratio Test (LRT)

The diagram below details the step-by-step statistical testing procedure for comparing two nested models.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Components for LR-Based Research

| Item / Concept | Function in the LR Framework | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Model | Provides the mathematical foundation to calculate the probability of the evidence under competing hypotheses (H₁ and H₂) [10]. | Used in all LR applications, from simple distributions to complex phylogenetic or machine learning models. |

| Nested Models | A prerequisite for performing the Likelihood-Ratio Test (LRT). Ensures the simpler model is a special case of the more complex one [8] [9]. | Critical for model selection tasks, such as choosing between DNA substitution models (e.g., HKY85 vs. GTR) [9]. |

| Pre-Test Probability | The initial estimate of the probability of the hypothesis before new evidence is considered. Serves as the baseline for Bayesian updating [7]. | Essential for converting an LR into a actionable post-test probability, especially in diagnostic and forensic decision-making. |

| Fagan Nomogram | A graphical tool that allows for the manual conversion of pre-test probability to post-test probability using a Likelihood Ratio, bypassing mathematical calculations [7]. | Used in medical diagnostics and other fields to quickly visualize the impact of evidence on the probability of a condition or hypothesis. |

| Chi-Square (χ²) Distribution | The reference distribution for the test statistic in a Likelihood-Ratio Test. Used to determine the statistical significance of the model comparison [9]. | Applied when determining if the fit of a more complex model is justified by a significant improvement in likelihood. |

Welcome to the Technical Support Center

This resource provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs for researchers in forensic comparison. The content supports thesis research on optimizing text sample size and addresses specific experimental challenges.

Frequently Asked Questions

Question: My dataset contains text from different registers (e.g., formal reports vs. informal chats), which is hurting model performance. How can I mitigate this register variation? Register variation introduces inconsistent linguistic features. Implement a multi-step preprocessing protocol:

- Register Identification: Use a pre-trained classifier (e.g., based on the

textregisterpackage in R) to label each text sample in your dataset by its register [11]. - Stratified Sampling: When creating training and test sets, ensure each set contains a proportional representation of all identified registers. This prevents the model from associating a linguistic feature with a specific topic simply because that topic was over-represented in a single register within your training data.

- Register-Specific Normalization: For certain features (e.g., lexical density, sentence length), calculate and apply normalization factors based on established baselines for each register.

Question: I suspect topic mismatch between my reference and questioned text samples is causing high false rejection rates. How can I diagnose and correct for this? Topic mismatch can cause two texts from the same author to appear dissimilar. To diagnose and correct [11]:

- Diagnosis: Extract the dominant topics from your text pairs using a topic modeling technique like Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA). A significant divergence in the primary topic distributions indicates potential topic mismatch.

- Correction: Instead of using raw term-frequency vectors, use a topic-agnostic feature set for author identification. Focus on stylistic features like:

- Function Words: The frequency of words like "the," "and," "of," which are largely independent of topic.

- Character N-Grams: Sub-word sequences that capture individual typing and spelling habits.

- Syntax and Punctuation: Patterns in sentence structure and the use of punctuation marks.

Question: I am working with a small, scarce dataset of text samples. What are the most effective techniques to build a robust model without overfitting? Data scarcity is a common constraint in forensic research. Employ these techniques to improve model robustness [12]:

- Feature Selection: Use a stringent feature selection method (e.g., Mutual Information, Chi-squared) to reduce the feature space to the most discriminative features for author identity. This lowers the model's complexity and reduces the risk of overfitting.

- Data Augmentation: Carefully create synthetic training examples. For text, this can include:

- Synonym Replacement: Swapping non-content words with their synonyms.

- Sentence Structuring: Slightly altering sentence structure while preserving meaning.

- Choose Simple Models: Start with simpler, more interpretable models (e.g., Logistic Regression, Support Vector Machines) rather than very complex deep learning models, which require vast amounts of data. You can then progress to complex models like ensemble methods.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: High Error Rates Due to Topic Mismatch

Symptoms: Your author identification model performs well on test data with similar topics but fails dramatically when applied to texts on new, unseen topics.

Resolution Steps:

- Confirm the Issue: Run your model on a controlled dataset where you know the author but the topics are varied. A significant performance drop confirms topic bias.

- Switch Feature Sets: Abandon topic-dependent vocabulary features. Retrain your model using a feature set comprised primarily of function words and character n-grams (e.g., 3-gram and 4-gram sequences).

- Validate: Use cross-validation on data with mixed topics to ensure the new model's performance is stable across topics. The performance should be more uniform, even if slightly lower on the original topic.

Verification Checklist:

- Topic influence has been quantified using LDA or similar analysis.

- Model has been retrained with a topic-agnostic feature set.

- Performance is now consistent across texts from different topics.

Issue: Model Instability from Data Scarcity

Symptoms: Model performance metrics (like accuracy) show high variance between different training runs or cross-validation folds. The model may also achieve 100% training accuracy but fail on validation data, a clear sign of overfitting.

Resolution Steps:

- Simplify the Model: Reduce the number of features by an additional 10-20% using a robust feature selection algorithm.

- Apply Regularization: If using a model like Logistic Regression, significantly increase the strength of the L2 (ridge) regularization parameter to penalize complex models.

- Use Heavy Cross-Validation: Implement a 10-fold or even leave-one-out cross-validation to get a more stable estimate of performance and to tune hyperparameters.

Verification Checklist:

- Feature space has been reduced to the essential.

- Regularization has been applied and tuned.

- Model performance is consistent across all cross-validation folds.

Experimental Protocols & Data

This table compares different linguistic feature types used in author identification, highlighting their robustness to topic variation, which is critical for optimizing text sample size research.

| Feature Type | Description | Robustness to Topic Variation | Ideal Sample Size (Words) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lexical (Content) [11] | Frequency of specific content words (nouns, verbs). | Low | 5,000+ |

| Lexical (Function) [11] | Frequency of words like "the," "it," "and." | High | 1,000 - 5,000 |

| Character N-Grams [11] | Sequences of characters (e.g., "ing," "the_"). | High | 1,000 - 5,000 |

| Syntactic | Patterns in sentence structure and grammar. | Medium | 5,000+ |

| Structural | Use of paragraphs, punctuation, etc. | Medium | 500 - 2,000 |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Forensic Text Analysis

This table details key digital tools and materials, or "research reagent solutions," essential for experiments in computational forensic text analysis.

| Item Name | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| NLTK / spaCy | Natural Language Processing (NLP) libraries used for fundamental tasks like tokenization (splitting text into words/sentences), part-of-speech tagging, and syntactic parsing [11]. |

| Scikit-learn | A core machine learning library used for feature extraction (e.g., converting text to n-grams), building author classification models (e.g., SVM, Logistic Regression), and evaluating model performance [12]. |

| Gensim | A library specifically designed for topic modeling (e.g., LDA) and learning word vector representations, which helps in diagnosing and understanding topic mismatch [11]. |

| Stratified Sampler | A script or function that ensures your training and test sets contain proportional representation of different text registers, mitigating bias from register variation. |

| Function Word List | A predefined list of high-frequency function words (e.g., based on the LIWC dictionary) used to create topic-agnostic feature sets for robust author comparison [11]. |

Experimental Workflow Visualization

Topic-Agnostic Author Identification

Mitigating Data Scarcity

Your Questions Answered

This guide addresses frequently asked questions to help you effectively implement and interpret Discrimination Accuracy and the Log-Likelihood-Ratio Cost (Cllr) in your forensic text comparison research.

FAQ 1: What are Discrimination and Calibration, and why are both important for my model?

In the context of a Likelihood Ratio (LR) system, performance is assessed along two key dimensions:

- Discrimination answers the question: "Can the system distinguish between authors? Does it correctly give higher LRs when

Hpis true and lower LRs whenHdis true?" It is a measure of the system's ability to rank or separate different authors. A highly discriminating model will provide strong, correct evidence. [13] [14] - Calibration answers the question: "Are the LR values it produces correct?" A well-calibrated system's LR values truthfully represent the strength of the evidence. For example, when it reports an LR of 1000, it should be 1000 times more likely to observe that evidence under

Hpthan underHd. Poor calibration leads to misleading evidence, either understating or overstating its value. [13]

A good system must excel in both. A system with perfect discrimination but poor calibration will correctly rank authors but give incorrect, potentially misleading, values for the strength of that evidence. [13]

FAQ 2: My system has a Cllr of 0.5. Is this a good result?

The Cllr is a scalar metric where a lower value indicates better performance. A perfect system has a Cllr of 0, while an uninformative system that always returns an LR of 1 has a Cllr of 1. [13] Therefore, 0.5 is an improvement over a naive system, but its adequacy depends on your specific application and the standards of your field.

To provide context, the table below shows Cllr values from a forensic text comparison experiment that investigated the impact of text sample size. As you can see, Cllr improves (decreases) substantially as the amount of text data increases. [15]

Table 1: Cllr Values in Relation to Text Sample Size in a Forensic Text Experiment [15]

| Text Sample Size (Words) | Reported Cllr Value | Interpretation (Discrimination Accuracy) |

|---|---|---|

| 500 | 0.68258 | ~76% |

| 1000 | 0.46173 | ~84% |

| 1500 | 0.31359 | ~90% |

| 2500 | 0.21707 | ~94% |

FAQ 3: I'm getting a high Cllr. How can I troubleshoot my system's performance?

A high Cllr indicates poor performance. You should first diagnose whether the issue is primarily with discrimination, calibration, or both. The Cllr can be decomposed into two components: Cllr_min (representing discrimination error) and Cllr_cal (representing calibration error), such that Cllr = Cllr_min + Cllr_cal. [13]

Table 2: Troubleshooting High Cllr Values

| Scenario | Likely Cause | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

High Cllr_min(Poor discrimination) |

The model's features or algorithm cannot effectively tell authors apart. [13] | 1. Feature Engineering: Explore more robust, topic-agnostic stylometric features (e.g., character-level features, syntactic markers). [1] [15] 2. Increase Data: Use larger text samples, as discrimination accuracy is highly dependent on sample size. [15] 3. Model Complexity: Ensure your model is sophisticated enough to capture author-specific patterns. |

High Cllr_cal(Poor calibration) |

The model's output LRs are numerically inaccurate, often overstating or understating the evidence. [13] | 1. Post-Hoc Calibration: Apply calibration techniques like Platt Scaling or Isotonic Regression (e.g., using the Pool Adjacent Violators (PAV) algorithm) to the raw model scores. [13] 2. Relevant Data: Ensure your validation data matches casework conditions (e.g., topic, genre, register) to learn a proper calibration mapping. [1] |

| Both are high | A combination of the above issues. | Focus on improving discrimination first, as a model that cannot discriminate cannot be calibrated. Then, apply calibration methods. |

FAQ 4: Why is it critical that my validation data matches real casework conditions?

Empirical validation is a cornerstone of a scientifically defensible forensic method. Using validation data that does not reflect the conditions of your case can severely mislead the trier-of-fact. [1]

For example, if you train and validate your model only on texts with matching topics, but your case involves a questioned text about sports and known texts by a suspect about politics, your validation results will be over-optimistic and invalid. [1] The system's performance can drop significantly when faced with this "mismatch in topics." Your validation must replicate this challenging condition using relevant data to provide a realistic measure of your system's accuracy. [1]

The following workflow summarizes the key steps for developing and validating a forensic text comparison system:

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Forensic Text Comparison

| Item / Concept | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Text Corpus | The foundational data. Must be relevant to casework, with known authorship and controlled variables (topic, genre) to test specific conditions like topic mismatch. [1] |

| Stylometric Features | The measurable units of authorship style. These can be lexical, character-based, or syntactic. Robust features (e.g., "Average character per word", "Punctuation ratio") work well across different text lengths and topics. [15] |

| Likelihood Ratio (LR) Framework | The logical and legal framework for evaluating evidence. It quantifies the strength of evidence by comparing the probability of the evidence under two competing hypotheses (prosecution vs. defense). [1] |

| Statistical Model (e.g., Dirichlet-Multinomial) | The engine that calculates the probability of the observed stylometric features under the Hp and Hd hypotheses, outputting an LR. [1] |

| Logistic Regression Calibration | A post-processing method to ensure the numerical LRs produced by the system are well-calibrated and truthfully represent the strength of the evidence. [1] [13] |

| Cllr (Log-Likelihood-Ratio Cost) | A strictly proper scoring rule that provides a single metric to evaluate the overall performance of an LR system, penalizing both poor discrimination and poor calibration. [13] |

| Tippett Plots | A graphical tool showing the cumulative distribution of LRs for both Hp-true and Hd-true conditions. It provides a visual assessment of system performance and the rate of misleading evidence. [1] [13] |

From Theory to Practice: Methodologies for Sample Size Analysis and Feature Selection

Experimental Designs for Quantifying Sample Size Impact on Accuracy

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is sample size so critical in forensic comparison research?

Sample size is fundamental because it directly influences the statistical validity and reliability of your findings [16]. An appropriately calculated sample size ensures your experiment has a high probability of detecting a true effect (e.g., a difference between groups or the accuracy of a method) if one actually exists [17]. In forensic contexts, this is paramount for satisfying legal standards like the Daubert criteria, which require that scientific evidence is derived from reliable principles and methods [18].

Using a sample size that is too small (underpowered) increases the risk of a Type II error (false negative), where you fail to detect a real difference or effect [17] [19]. This can lead to inconclusive or erroneous results that may not be admissible in court. Conversely, an excessively large sample (overpowered) can detect minuscule, clinically irrelevant differences as statistically significant, wasting resources and potentially exposing more subjects than necessary to experimental procedures [20]. A carefully determined sample size balances statistical rigor with ethical and practical constraints [21] [17].

Q2: What are the key parameters I need to calculate a sample size?

Calculating a sample size requires you to define several key parameters in advance. These values are typically obtained from pilot studies, previous published literature, or based on a clinically meaningful difference [21] [22].

Table 1: Essential Parameters for Sample Size Calculation

| Parameter | Description | Common Values in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Effect Size | The minimum difference or treatment effect you consider to be scientifically or clinically meaningful [21] [20]. | A standardized effect size (e.g., Cohen's d) of 0.5 is a common "medium" effect [21]. |

| Significance Level (α) | The probability of making a Type I error (false positive)—rejecting the null hypothesis when it is true [17]. | Usually set at 0.05 (5%) [21] [17]. |

| Statistical Power (1-β) | The probability of correctly rejecting the null hypothesis when it is false (i.e., detecting a real effect) [17]. | Typically 80% or 90% [21] [17]. |

| Variance (SD) | The variability of your primary outcome measure [22]. | Estimated from prior data or pilot studies. |

| Dropout Rate | The anticipated proportion of subjects that may not complete the study [21]. | Varies by study design and duration; must be accounted for in final recruitment. |

Q3: How do I adjust for participants who drop out of my study?

It is crucial to adjust your calculated sample size to account for participant dropout to maintain your study's statistical power. A common error is to simply multiply the initial sample size by the dropout rate. The correct method is to divide your initial sample size by (1 – dropout rate) [21].

Formula: Adjusted Sample Size = Calculated Sample Size / (1 – Dropout Rate)

Example: If your power analysis indicates you need 50 subjects and you anticipate a 20% dropout rate:

- Incorrect Calculation: 50 × (1 + 0.20) = 60

- Correct Calculation: 50 / (1 - 0.20) = 50 / 0.80 = 62.5 → Round up to 63 subjects [21].

Q4: My experiment yielded a statistically significant result with a very small effect. Is this valid?

While the result may be statistically valid, its practical or clinical significance is questionable [20] [16]. With a very large sample size, even trivially small effects can achieve statistical significance because the test becomes highly sensitive to any deviation from the null hypothesis [20]. In forensic research, you must ask if the observed effect is large enough to be meaningful in a real-world context. A result might be statistically significant but forensically irrelevant. The magnitude of the difference and the potential for actionable insights are as important as the p-value [16].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Underpowered Experiment Leading to Inconclusive Results

Symptoms: Your study fails to find a statistically significant effect, even though you suspect one exists. The confidence intervals for your primary metric (e.g., sensitivity/specificity, effect size) are very wide [19].

Root Causes:

- Insufficient sample size due to inaccurate initial estimates [21].

- Higher-than-expected variability in the outcome measure [22].

- Smaller-than-expected effect size [22].

Solutions:

- Conduct an A Priori Power Analysis: Before the experiment, use the parameters in Table 1 to calculate the required sample size using dedicated software (e.g., G*Power, nQuery) or validated formulas [22].

- Increase Sample Size: If possible, recruit more subjects to increase the power of your study.

- Improve Measurement Precision: Refine your experimental protocols or use more precise equipment to reduce measurement variability [23].

- Use a More Sensitive Design: Employ within-subjects (paired) designs or blocking factors that control for known sources of variability, which can increase power without increasing sample size [22].

The following workflow can help diagnose and address power issues:

Problem: Overpowered Experiment Detecting Clinically Irrelevant Effects

Symptoms: Your study finds a statistically significant result, but the effect size is so small it has no practical application in forensic casework [20].

Root Causes:

- Excessively large sample size beyond what is required for detecting a meaningful effect [20].

Solutions:

- Justify the Effect Size: When designing the study, base your effect size on a minimal clinically important difference (MCID) or a forensically relevant threshold, not an arbitrary small value [21] [20].

- Report Effect Sizes and Confidence Intervals: Always present the magnitude of the effect (e.g., Cohen's d, mean difference) alongside p-values, so readers can judge its practical significance [16].

- Re-evaluate Objectives: Ensure the study's goal is to detect a meaningful difference, not just any statistical difference.

Problem: High Uncertainty in Validation of Forensic Comparison Systems

Symptoms: When validating an Automatic Speaker Recognition (ASR) system or similar forensic comparison tool, performance metrics (e.g., Cllr, EER) vary considerably between tests, undermining reliability [24].

Root Causes:

- Sampling Variability: Using different, non-representative subsets of data for training and testing the system [24].

- Inconsistent Experimental Conditions: Changes in recording devices, background noise, or session conditions between samples [24].

- Inadequate Sample Size for Validation: The number of voice samples or comparisons is too low to produce stable, generalizable performance estimates [24].

Solutions:

- Standardize Data Collection: Implement strict protocols for recording samples to minimize extraneous variability [23] [24].

- Use Representative Populations: Ensure your reference and test populations accurately reflect the relevant population for your forensic context [24].

- Increase Sample Size in Validation Studies: Power your validation studies to precisely estimate key metrics like sensitivity and specificity or to achieve a narrow confidence interval for the log-LR cost function (Cllr) [24] [19].

Table 2: Key Resources for Experimental Design and Sample Size Calculation

| Tool / Resource | Category | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| G*Power [22] | Software | A free, dedicated tool for performing power analyses and sample size calculations for a wide range of statistical tests (t-tests, F-tests, χ² tests, etc.). |

| nQuery [17] | Software | A commercial, validated sample size software package often used in clinical trial design to seek regulatory approval. |

| R (pwr package) | Software | A powerful, free statistical programming environment with packages dedicated to power analysis. |

| Standardized Protocols (SOPs) | Methodology | Detailed, step-by-step procedures for data collection and analysis to reduce inter-experimenter variability and improve reproducibility [23] [24]. |

| Pilot Study Data | Data | A small-scale preliminary study used to estimate the variance and effect size needed for a robust power analysis of the main study [22]. |

| Cohen's d [21] | Statistic | A standardized measure of effect size, calculated as the difference between two means divided by the pooled standard deviation, allowing for comparison across studies. |

| Likelihood Ratio (LR) [19] | Statistic | In diagnostic and forensic studies, the LR quantifies how much a piece of evidence (e.g., a voice match) shifts the probability towards one proposition over another. |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What are the core categories of stylometric features I should consider for authorship attribution? A: Robust stylometric analysis typically relies on features categorized into several groups. The core categories include Lexical Diversity (e.g., Type-Token Ratio, Hapax Legomenon Rate), Syntactic Complexity (e.g., average sentence length, contraction count), and Character-Based Metrics (e.g., total character count, average word length). Additional informative categories are Readability, Sentiment & Subjectivity, and Uniqueness & Variety (e.g., bigram/trigram uniqueness) [25].

Q: Why is my stylometric model failing to generalize to texts from a different domain? A: This is often due to domain-dependent features. A model trained on, for instance, academic papers might perform poorly on social media texts because of differences in vocabulary, formality, and sentence structure. The solution is to prioritize robust, domain-agnostic features. Function words and character-based metrics are generally more stable across domains than content-specific vocabulary. Techniques like Burrows' Delta, which focuses on the most frequent words, are designed to be largely independent of content and can improve cross-domain performance [26].

Q: How does sample size impact the reliability of stylometric features? A: Sample size is critical. Larger text samples provide more stable and reliable estimates for frequency-based features like word or character distributions. A common issue is that Lexical Diversity features, such as the Type-Token Ratio, are highly sensitive to text length. As text length increases, the TTR naturally decreases. For short texts, it is advisable to use features less sensitive to length or to apply normalization techniques [25].

Q: What is the minimum text length required for a reliable analysis? A: There is no universal minimum, as it depends on the features used. However, for methods like Burrows' Delta, which relies on the stable frequency of common words, a text of at least 1,500-2,000 words is often considered a reasonable starting point for reliable analysis. For shorter texts, you may need to focus on a smaller set of the most frequent words or use specialized methods designed for micro-authorship attribution [26].

Q: My dataset has imbalanced authorship. How does this affect feature selection? A: Imbalanced datasets can bias models towards the author with more data. When selecting features, prioritize those that are consistent within an author's style but discriminative between authors. Techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or feature importance scores from ensemble methods like Random Forest can help identify the most discriminative features for your specific dataset, mitigating the effects of imbalance [25].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Applying Burrows' Delta for Stylometric Comparison

This protocol is used to quantify stylistic similarity and cluster texts based on the frequency of their most common words [26].

- Corpus Preparation: Compile a collection of texts from different authors or sources (e.g., human-authored and AI-generated). Ensure texts are in plain text format and perform minimal preprocessing (e.g., lowercasing).

- Feature Extraction: Identify the N Most Frequent Words (MFW) across the entire corpus. Typically, function words (e.g., "the," "and," "of") are used as they are less topic-dependent.

- Frequency Matrix Creation: Create a matrix where rows represent texts and columns represent the N MFW. Each cell contains the normalized frequency of a word in a text.

- Standardization (Z-scores): Convert the frequency matrix to Z-scores to normalize the data across features.

- Calculate Delta: For each pair of texts, calculate Burrows' Delta, which is the mean of the absolute differences between their Z-scores for all MFW. A lower Delta indicates greater stylistic similarity.

- Clustering and Visualization: Use the resulting distance matrix to perform hierarchical clustering and create a dendrogram. Alternatively, use Multidimensional Scaling (MDS) to project the relationships into a 2D scatter plot for visual inspection [26].

Protocol 2: Implementing a Stylometric Feature-Based Classifier

This protocol outlines the steps for building a machine learning classifier using a wide array of stylometric features [25].

- Data Collection and Annotation: Gather a dataset of texts and label them by author or class (e.g., Human vs. AI). The Beguš corpus, used in recent studies, is an example containing 250 human-written and 130 AI-generated stories [26].

- Comprehensive Feature Extraction: For each text, extract a wide range of features. The table below details the core features to calculate.

- Data Preprocessing: Handle missing values and normalize feature values to a common scale (e.g., 0 to 1) to prevent features with larger ranges from dominating the model.

- Model Training: Split the data into training and testing sets. Train a classifier such as a Random Forest, which is effective for this task and can provide feature importance scores [25].

- Model Evaluation: Evaluate the model on the held-out test set using metrics like accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score.

- Feature Analysis: Examine the model's feature importance rankings to identify which stylometric features were most discriminative for your specific authorship attribution task.

Stylometric Feature Tables

Table 1: Core Stylometric Features for Analysis

| Feature Category | Feature Name | Description | Key Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lexical Diversity | Type-Token Ratio (TTR) | Ratio of unique words to total words. | Measures vocabulary richness and repetition [25]. |

| Hapax Legomenon Rate | Proportion of words that appear only once. | Induces lexical sophistication and rarity [25]. | |

| Character & Word-Based | Word Count | Total number of words. | Basic metric for text length [25]. |

| Character Count | Total number of characters. | Basic metric for text length and density [25]. | |

| Avg. Word Length | Average number of characters per word. | Reveals preference for simple or complex words [25]. | |

| Syntactic Complexity | Avg. Sentence Length | Average number of words per sentence. | Indicates sentence complexity [25]. |

| Contraction Count | Number of contracted forms (e.g., "don't"). | Suggests informality of style [25]. | |

| Complex Sentence Count | Number of sentences with multiple clauses. | Measures syntactic sophistication [25]. | |

| Readability | Flesch Reading Ease | Score based on sentence and word length. | Quantifies how easy the text is to read [25]. |

| Gunning Fog Index | Score based on sentence length and complex words. | Estimates the years of formal education needed to understand the text [25]. | |

| Sentiment & Subjectivity | Polarity | Intensity of the positive/negative emotional tone. | Assesses emotional tone [25]. |

| Subjectivity | Degree of personal opinion vs. factual content. | Measures objectivity of the text [25]. | |

| Uniqueness & Variety | Bigram/Trigram Uniqueness | Ratio of unique word pairs/triples to total. | Captures phrasal diversity and creativity [25]. |

Table 2: Experimental Dataset Profile (Beguš Corpus)

This table summarizes a modern dataset used for comparing human and AI-generated creative writing [26].

| Parameter | Description |

|---|---|

| Source | Open dataset created by Nina Beguš (2023) for behavioral and computational analysis [26]. |

| Total Texts | 380 short stories (250 human, 80 from GPT-3.5/GPT-4, 50 from Llama 3-70b) [26]. |

| Human Collection | Crowdsourced via Amazon Mechanical Turk [26]. |

| AI Models | OpenAI's GPT-3.5, GPT-4, and Meta's Llama 3-70b [26]. |

| Text Length | 150–500 words per story [26]. |

| Prompt Example | "A human created an artificial human. Then this human (the creator/lover) fell in love with the artificial human." [26]. |

| Key Finding | Human texts form heterogeneous clusters, while LLM outputs display high stylistic uniformity and cluster tightly by model [26]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Stylometric Analysis |

|---|---|

| Python (Natural Language Toolkit) | A primary programming environment for implementing stylometric algorithms, text preprocessing, and feature extraction [26]. |

| Burrows' Delta Method | A foundational algorithm for quantifying stylistic difference between texts based on the most frequent words, widely used in computational literary studies [26]. |

| Random Forest Classifier | A robust machine learning algorithm effective for authorship attribution tasks; it handles high-dimensional feature spaces well and provides feature importance scores [25]. |

| Hierarchical Clustering | A technique used to visualize stylistic groupings (clusters) of texts, often output as a dendrogram based on a distance matrix like Burrows' Delta [26]. |

| Multidimensional Scaling (MDS) | A visualization technique that projects high-dimensional stylistic distances (e.g., from Burrows' Delta) into a 2D or 3D scatter plot for easier interpretation [26]. |

| Pre-annotated Corpora | Gold-standard datasets (e.g., the Beguš corpus) used to train, test, and validate stylometric models in controlled experiments [26]. |

Workflow Diagram

Stylometric Analysis Workflow

Multivariate Statistical Models for Authorship Attribution (e.g., Dirichlet-Multinomial, Kernel Density)

Core Concepts & Troubleshooting

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the fundamental differences between the Dirichlet-Multinomial and Kernel Density Estimation models for authorship attribution?

The Dirichlet-Multinomial model and Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) are fundamentally different in their approach. The Dirichlet-Multinomial is a discrete, count-based model ideal for textual data represented as multivariate counts (e.g., frequencies of function words, character n-grams) [27] [1]. It explicitly models the overdispersion often found in such count data. In contrast, KDE is a non-parametric, continuous model used to estimate the probability density function of stylistic features [28] [29]. It is a powerful tool for visualizing and estimating the underlying distribution of continuous data points, such as measurements derived from text.

Q2: My authorship attribution system performs well on same-topic texts but fails on cross-topic comparisons. What is the cause and solution?

This is a classic challenge. The performance drop is likely due to the system learning topic-specific features instead of author-specific stylistic markers [1]. A text is a complex reflection of an author's idiolect, their social group, and the communicative situation (e.g., topic, genre). When topics differ, topic-related features become confounding variables [1].

- Solution: Ensure your validation experiments replicate the conditions of your case. If the case involves cross-topic comparison, your validation must use data with similar topic mismatches [1]. Furthermore, prioritize style markers that are topic-invariant, such as:

Q3: How can I determine the optimal text sample size for a reliable analysis?

There is no universal minimum size, as it depends on the distinctiveness of the author's style and the features used. However, established methodologies involve data segmentation and empirical testing [30]. A common experimental approach is to segment available texts (e.g., novels) into smaller pieces based on a fixed number of sentences to create multiple data instances for training and testing attribution algorithms [30]. The reliability of attribution for different segment sizes can then be evaluated to establish a practical minimum for your specific context.

Q4: My model is vulnerable to authorship deception (style imitation or anonymization). How can I improve robustness?

This is a significant, unsolved challenge. Research indicates that knowledgeable adversaries can substantially reduce attribution accuracy [30]. No current method is fully robust against targeted attacks [30]. Future directions include exploring cognitive signatures—deeper, less consciously controllable features of an author's writing derived from cognitive processes [30].

Common Error Messages and Resolutions

| Error Scenario / Symptom | Likely Cause | Resolution Steps |

|---|---|---|

| Poor performance on cross-topic texts [1] | Model is relying on content-specific words instead of topic-agnostic style markers. | 1. Re-validate using topic-mismatched data [1].2. Re-engineer features: use function words, POS tags, and syntactic patterns [30]. |

| Model fails to distinguish between authors | Features lack discriminative power, or text samples are too short. | 1. Perform feature selection using Mutual Information or Chi-square tests [30].2. Experiment with sequential data mining techniques (e.g., sequential rule mining) [30]. |

| High variance in model performance | Data sparsity or overfitting, common with high-dimensional text data. | 1. Increase the amount of training data per author, if possible.2. For Dirichlet-Multinomial, ensure the model's dispersion parameter is properly accounted for [27] [31]. |

| Inability to handle zero counts or sparse features | Probabilistic models can assign zero probability to unseen features. | Use smoothing techniques. The Dirichlet prior in the Dirichlet-Multinomial model naturally provides smoothing for multinomial counts [27]. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Standard Protocol for Authorship Attribution

This protocol outlines the general workflow for building an authorship attribution model, adaptable for both Dirichlet-Multinomial and KDE approaches.

Workflow for Authorship Attribution

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Data Collection & Preparation

- Gather a corpus of texts from known candidate authors. The number of texts and their length should be documented.

- For forensic validation, ensure the data is relevant to the case conditions (e.g., topic, genre) [1].

Preprocessing

- Tokenization: Split text into tokens (words, punctuation).

- Normalization: Convert to lowercase, handle punctuation (may be used for sentence segmentation [30]).

- POS Tagging: Assign part-of-speech tags to each word [30].

- Sentence Segmentation: Split texts into sentences using punctuation marks {

.,!,?,:,…} for finer-grained analysis [30].

Feature Extraction & Selection

- Extract stylometric features:

- Apply feature selection (e.g., Mutual Information, Chi-square) to reduce dimensionality and retain the most discriminative features [30].

Model Selection & Training

- For Multivariate Count Data: Use the Dirichlet-Multinomial model. It is appropriate when your feature vector represents counts across categories (e.g., counts of different words or n-grams) and you need to account for overdispersion [27] [31].

- For Continuous Features: Use Kernel Density Estimation. KDE can estimate the probability density of continuous stylistic measurements, providing a smooth and detailed representation of an author's style [28] [29].

- Train the model on a labeled dataset, using a hold-out set or cross-validation.

Evaluation & Interpretation

- Evaluate performance on a separate test set using metrics like accuracy.

- In a forensic context, report results using the Likelihood Ratio (LR) framework, which quantifies the strength of evidence for one authorship hypothesis over another [1].

Quantitative Data from Experimental Studies

The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from authorship attribution research, which can serve as benchmarks for your own experiments.

Table 1: Performance Benchmarks in Authorship Attribution

| Domain / Data Type | Methodology | Key Performance Metric | Result / Benchmark | Citation Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Email Authorship (Enron corpus) | Decision Trees, Support Vector Machines | Attribution Accuracy | ~80% accuracy (4 suspects)~77% accuracy (10 suspects) | [30] |

| Source Code Authorship (C++ programs) | Frequent N-grams, Intersection Similarity | Attribution Accuracy | 100% accuracy (6 programmers) | [30] |

| Source Code Authorship (Java programs) | Frequent N-grams, Intersection Similarity | Attribution Accuracy | Up to 97% accuracy | [30] |

| Natural Language Text (40 novels, 10 authors) | Stylometric Features (e.g., POS n-grams) | Attribution Accuracy | High accuracy reported, methodology requires segmentation into sentences for sufficient data | [30] |

| Multimodal Data PDF Estimation | Data-driven Fused KDE (DDF-KDE) | Estimation Error | Lower estimation error and superior PDF approximation vs. 5 other classic KDEs | [28] |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Tools for Authorship Attribution Research

| Item Name | Function / Purpose | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Stylometric Feature Set | To provide a numerical representation of writing style for model training. | Includes function word frequencies, character n-grams (n=3,4), and POS n-grams [30]. |

| Dirichlet-Multinomial Regression Model | To model multivariate count data (e.g., word counts) while accounting for overdispersion and covariance structure between features. | Can be implemented with random effects to model within-author correlations [31]. Useful for microbiome-like data structures [27]. |

| Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) | A non-parametric tool to estimate the probability density function of continuous stylistic features, visualizing intensity distribution [29]. | Bandwidth selection is critical. Advanced methods like Selective Bandwidth KDE can be used for data correction [32]. |

| Likelihood Ratio (LR) Framework | The logically and legally correct framework for evaluating forensic evidence strength, separating similarity and typicality [1]. | Calculated as LR = p(E|Hp) / p(E|Hd). Requires calibration and validation under case-specific conditions [1]. |

| Sequential Rule Miner | To extract linguistically motivated style markers that capture latent sequential information in text, going beyond bag-of-words. | Can be used to find sequential patterns between words or POS tags, though may not outperform simpler features like function words [30]. |

How does increasing the text sample size from 500 to 2500 words impact the statistical power of a forensic comparison?

Increasing the text sample size directly enhances the statistical power of a forensic comparison, which is the probability of correctly identifying a true effect or difference between authors. A larger sample size improves the experiment in several key ways:

- Reduced Error Rates: It directly lowers the likelihood of both Type I errors (falsely identifying a non-existent author match) and Type II errors (failing to identify a true author match) [33]. The sample size calculation is specifically designed to ensure the study is powered to a nominal level (e.g., 80% or 90%) for the expected effect size [33].

- Improved Parameter Estimation: Larger samples provide more reliable and precise estimates of crucial textual features, such as the frequency of specific function words or syntactic patterns. This is analogous to more accurately estimating the sensitivity and specificity of a diagnostic test [33].

- Accounting for Conditional Dependence: In paired study designs (e.g., comparing two attribution methods on the same text samples), the required sample size is heavily influenced by the conditional dependence between the methods—the lower the dependence, the larger the sample size required for the same power. A larger sample provides a better basis for estimating this dependence and ensuring the study is sufficiently powered [33].

The table below summarizes the quantitative relationship between sample size and key statistical parameters, based on principles from diagnostic study design [33].

| Statistical Parameter | Impact of Increasing Sample Size (500 to 2500 words) |

|---|---|

| Statistical Power | Increases, reducing Type II error rates. |

| Estimation Precision | Improves reliability of feature prevalence measurements. |

| Handling of Conditional Dependence | Allows for more robust analysis of interrelated textual features. |

| Confidence Interval Width | Narrows, providing a more precise range for effect sizes. |

What is a standard experimental protocol for determining the correct sample size in a text comparison study?

A robust protocol involves an initial calculation followed by a potential re-estimation at an interim analysis point. This two-stage approach ensures resources are used efficiently without compromising the study's validity [33].

Initial Sample Size Calculation: This calculation should be performed for each primary objective of the study (e.g., power based on a specific lexical feature and on a syntactic feature). The final sample size is the largest number calculated from these different objectives [33]. The formula for a comparative diagnostic study, adapted for text analysis, is structured as follows for a single objective (e.g., sensitivity/recall):

n = [ (Z_(1-β) + Z_(1-α/2)) / log(γ) ]² * [ (γ + 1) * TPR_B - 2 * TPPR ] / [ γ * TPR_B² * π ]

Where:

n: Required sample size.Z_(1-β): Z-score for the desired statistical power.Z_(1-α/2): Z-score for the significance level (alpha).γ: The ratio of true positive rates (e.g.,TPR_Method_A / TPR_Method_B) you want to be able to detect.TPR_B: The expected true positive rate (sensitivity/recall) of the existing method.TPPR: The proportion of text samples where both methods correctly identify the author.π: The prevalence of the textual feature in the population.

Interim Sample Size Re-estimation:

- Plan an Interim Analysis: Pre-determine the point at which you will re-estimate the sample size, for example, after collecting 60% of the initially calculated samples [33].

- Collect Interim Data: Gather the planned interim data on your textual features and author attribution results.

- Re-estimate Nuisance Parameters: Use the interim data to recalculate key parameters that were initially unknown or estimated, such as the actual conditional dependence between two analysis methods or the true prevalence of a rare textual feature [33].

- Re-calculate the Final Sample Size: Plug the updated parameters from the interim analysis back into the sample size formula.

- Continue the Experiment: Complete the data collection using the newly calculated sample size. This method has been shown to maintain stable Type I error rates and achieve nominal statistical power while potentially reducing the total number of samples required [33].

Sample Size Determination Workflow

Our initial sample size calculation relied on an estimated effect size. The interim data suggests the effect is smaller. How do we re-estimate the sample size without inflating Type I error?

This is a common challenge, and a formal sample size re-estimation (SSR) procedure is the solution. When using a pre-planned interim analysis to re-estimate a nuisance parameter (like the true effect size or conditional dependence), the overall Type I error rate of the study remains stable [33]. The key is that the re-estimation is based only on the observed interim data for these parameters and does not involve a formal hypothesis test about the primary outcome at the interim stage.

Methodology for SSR Based on Interim Data:

- Pre-specification: The plan for SSR must be documented before the study begins, including the timing of the interim analysis and which parameters will be re-estimated [33].

- Data Collection at Interim: At the pre-specified point, collect data on the

ntext samples. - Parameter Estimation: Use the interim data to calculate the maximum likelihood estimates for the initially unknown parameters. In a paired comparative study, this often involves estimating the conditional dependence between two tests or methods under a multinomial model for the data distribution [33].

- Sample Size Update: Input the updated, data-driven parameter estimates into the original sample size formula. This will give a new target sample size (

N_final). - Completion: Continue the experiment until

N_finalis reached, then perform the final hypothesis test on the complete dataset. Simulation studies have confirmed that this procedure maintains the nominal Type I error rate and ensures power is close to or above the desired level [33].

What are the essential "research reagents" or key components for a rigorous text sample size study?

A well-equipped methodological toolkit is essential for conducting a robust sample size study in forensic text comparison. The table below details these key components.

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Gold Standard Corpus | A curated collection of texts with verified authorship. Serves as the objective benchmark against which attribution methods are measured [33]. |

| Text Feature Extractor | Software or algorithm to identify and quantify linguistic features (e.g., n-grams, syntax trees, word frequencies). These features are the raw data for comparison. |

| Statistical Power Analysis Software | Tools (e.g., R, PASS) used to perform the initial and interim sample size calculations, incorporating parameters like effect size and alpha. |

| Paired Study Design Framework | A protocol for comparing two analytical methods on the exact same set of text samples. This controls for text-specific variability and allows for the assessment of conditional dependence [33]. |

| Interim Analysis Protocol | A pre-defined plan for when and how to examine the interim data to re-estimate parameters, ensuring the study's integrity is maintained [33]. |

Components of a Text Sample Size Study

Operational Guidelines for Minimum Sample Size in Casework

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the core principle for determining a minimum sample size in forensic text comparison?

The core principle is that sample data must be representative of both the specific examiner and the specific conditions of the case under investigation [34]. Using data pooled from multiple examiners or different casework conditions can lead to likelihood ratios (LRs) that are not meaningful for your specific case, potentially misleading the trier-of-fact [34] [1].

FAQ 2: Why can't I just use a single, fixed sample size for all my casework?

A fixed sample size is insufficient because the required sample size is directly tied to the specific hypotheses you are testing and the statistical power you need to achieve [35]. For instance, a design verification test might be valid with a sample size of n=1 if it is a worst-case challenge test with a "bloody obvious" result, whereas a process validation, which must account for process variation, might require a larger sample, such as n=15 [35]. The appropriate sample size depends on the specific statistical question being asked.

FAQ 3: How do I collect performance data for a specific examiner?

Collecting a large amount of performance data for a single examiner can be challenging. A proposed solution is a Bayesian method [34]:

- Informed Priors: Use a large amount of response data from multiple examiners to establish prior models for same-source and different-source probabilities.

- Update with Specific Data: Use the smaller amount of data available from the particular examiner to update these prior models into posterior models.

- Continuous Improvement: Integrate blind test trials into the examiner's regular workflow. Over time, as more data is collected from that examiner, the calculated LRs will become more reflective of their individual performance [34].

FAQ 4: What are the key requirements for empirical validation in forensic text comparison?

For empirical validation to be meaningful, two main requirements must be met [1]:

- Reflect Case Conditions: The validation must replicate the conditions of the case under investigation (e.g., mismatched topics between documents).

- Use Relevant Data: The data used for validation must be relevant to the specific case.