Non-Contact Sampling for Explosive Trace Detection: Technologies, Applications, and Future Directions

This article provides a comprehensive overview of non-contact sampling methods for explosive trace detection, tailored for researchers, scientists, and security technology developers.

Non-Contact Sampling for Explosive Trace Detection: Technologies, Applications, and Future Directions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of non-contact sampling methods for explosive trace detection, tailored for researchers, scientists, and security technology developers. It explores the fundamental principles and operational challenges of detecting ultra-low vapor pressure compounds. The scope ranges from foundational technologies like Ion Mobility Spectrometry (IMS) and Ambient Ionization Mass Spectrometry (AIMS) to advanced field applications and sensor optimization strategies. A thorough analysis of validation protocols and comparative performance between leading technologies such as SERS, GC-MS, and emerging core-sheath architectures is presented, offering a complete resource for professionals developing next-generation detection systems.

Principles and Challenges of Non-Contact Explosive Vapor Detection

The Critical Need for Non-Contact Sampling in Security and Defense

The detection of trace explosives is a critical component of modern security screening, yet conventional methods face significant operational limitations. Current standard practices predominantly rely on contact sampling (swabbing), where surfaces are physically wiped to collect microparticles that may contain explosive residues [1]. This approach presents inherent vulnerabilities, including variable sampling efficiency influenced by surface properties, particle types, and operator technique [1]. Perhaps most critically, surface sampling only collects from a small fraction of the total surface area, increasing the probability of missing residual traces of explosives [1].

Non-contact sampling methods represent a paradigm shift in security screening, potentially overcoming these limitations by permitting larger sampling areas, enabling direct passenger screening for vapor and particle sampling, and reducing costs per sample [1]. This application note examines the scientific basis, recent technological advances, and practical implementation protocols for non-contact sampling technologies within the broader context of explosive trace detectors (ETDs) research.

Technological Approaches to Non-Contact Detection

Vapor-Based Detection Systems

Explosive vapor detection has been recognized as an optimal method for standoff detection as it is inherently non-contact [1]. The primary scientific challenge lies in the extremely low vapor pressures of many target explosive compounds, which range from parts per trillion (pptv) to sub-parts per quadrillion (ppqv) [1]. Vapor dilution in air further complicates detection, often requiring sensitivity below the pptv level [1].

Recent advancements in atmospheric pressure ionization techniques coupled with mass spectrometry have enabled molecular detection of explosive vapors at these challenging concentration levels. Specifically, atmospheric flow tube-mass spectrometry (AFT-MS) and secondary electrospray ionization (SESI) have demonstrated the ability to detect explosive vapors at pptv to ppqv concentrations [1]. These technological developments now make feasible non-contact detection for practical security screening applications.

Spectroscopy-Based Techniques

Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) has emerged as a powerful analytical technique for non-contact explosive detection. SERS achieves remarkable sensitivity, potentially enabling single-molecule detection through the use of noble metal substrates or structures [2]. This technique provides a distinct molecular "fingerprint" that can differentiate very similar compounds with high specificity, making it particularly valuable for identifying specific explosive compounds in complex environments [2].

Other spectroscopic methods showing promise include time-gated Raman spectroscopy, which utilizes a pulsed laser and an intensifier-charge coupled device (ICCD) synchronized with the optical pulse based on stand-off distance [2]. This approach is particularly well-suited for standoff detection scenarios where distance between the detector and potential threat is a operational requirement.

Quantitative Analysis of Non-Contact Detection Performance

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Explosive Trace Detection Technologies

| Technology | Detection Principle | Standoff Distance | Key Explosives Detected | Sensitivity Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AFT-MS with High-Volume Sampler | Vapor collection with mass spectrometry | Up to 2.5 meters [1] | RDX, Nitroglycerin [1] | Sub-pptv to ppqv [1] |

| SERS | Enhanced Raman scattering | Centimeter to meter scale [2] | Nitroaromatics, peroxide-based explosives [2] | Single-molecule detection potential [2] |

| Ion Mobility Spectrometry (IMS) | Gas phase ion separation at atmospheric pressure | Limited (typically requires proximity) [2] | TNT, RDX, PETN [2] | Nanogram to picogram [2] |

| GC-MS | Separation followed by mass analysis | Limited (typically requires collection) [2] | TNT, RDX, TATP [2] | Trace amounts (varies by compound) [2] |

Table 2: Market Analysis and Implementation Scope for ETD Systems

| Parameter | Current Market Value (2024) | Projected Market Value (2035) | Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) | Leading Application Sectors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global ETD Market | USD 6.92 Billion [3] | USD 12.96 Billion [3] | 6.48% (2025-2035) [3] | Aviation, Defense, Critical Infrastructure [3] |

| Regional Adoption | North America: Highest demand [3] | Asia Pacific: Fastest growth [3] | - | Transportation hubs, government facilities [3] |

Experimental Protocol: Standoff Vapor Detection Using AFT-MS

Principle and Scope

This protocol describes a methodology for standoff detection of explosive vapors at meter distances by combining Atmospheric Flow Tube-Mass Spectrometry (AFT-MS) with a high-volume air sampler, based on experimental work documented by Nims et al. [1]. The method leverages high-volume air collection to increase the effective distance for explosive vapor detection by overcoming natural air currents and vapor dilution effects.

Materials and Equipment

- Atmospheric Flow Tube-Mass Spectrometer (AFT-MS) system

- High-volume air sampler (flow rate: 225-240 L/min) [1]

- Explosive vapor standards (e.g., RDX, nitroglycerin)

- Saturated vapor source for calibration

- Laboratory space with controlled air currents (∼8m × ∼8m × ∼2.6m used in reference study) [1]

- Standard laboratory safety equipment

Procedure

System Calibration:

- Establish a saturated RDX vapor source within the testing environment.

- Position the AFT-MS system and connect the high-volume air sampler.

- Calibrate the mass spectrometer for target compounds using standard procedures.

Experimental Setup:

- Place the vapor source in a location with measurable air currents.

- Position the high-volume air sampler at predetermined distances from the vapor source (0.5m, 1m, 2.5m).

- Ensure the sampler is oriented to collect air from the direction of the vapor source.

Sample Collection:

- Activate the high-volume air sampler at its operational flow rate (225-240 L/min).

- Collect air samples for predetermined time intervals (typically 5-10 minutes).

- Direct the collected air samples into the AFT-MS for analysis.

Downstream and Upstream Testing:

- Perform comparative testing with the sampler positioned both downstream and upstream from the vapor source relative to room air currents.

- Record detection signals at each position to determine optimal placement.

Data Analysis:

- Monitor mass spectra for characteristic ions of target explosives (e.g., RDX at m/z 257.1083, 129.0656) [1].

- Compare signal intensities at different distances to establish detection limits.

- Evaluate the impact of room air currents on detection sensitivity.

Expected Results

When properly implemented, this protocol should demonstrate:

- Reliable vapor detection at distances up to 2.5 meters from a saturated RDX vapor source [1]

- Detection capability both downstream and upstream of the vapor source, with stronger signals typically observed in downstream positions [1]

- Signal intensity correlation with sampler positioning relative to room air currents

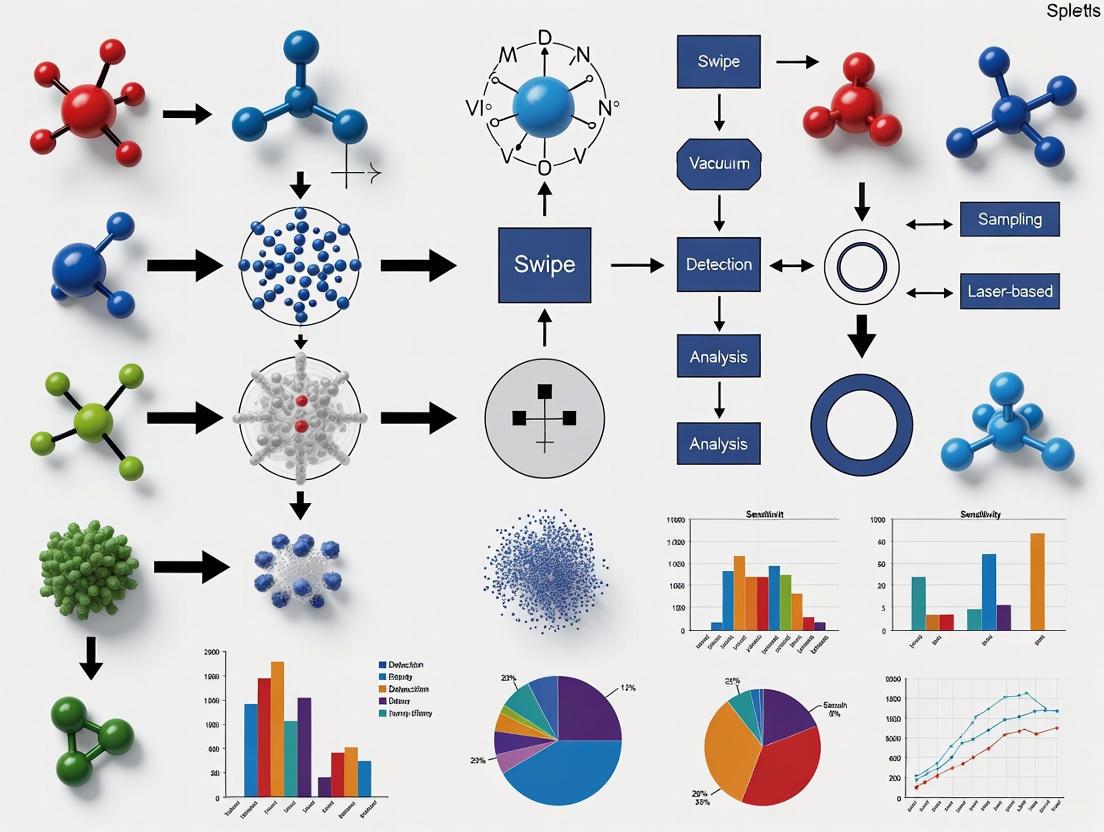

Workflow Visualization: High-Volume Air Sampling for Standoff Detection

Non-Contact Vapor Detection Workflow: This diagram illustrates the sequential process for standoff explosive vapor detection using high-volume air sampling coupled with AFT-MS analysis.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials for Non-Contact ETD Research

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Equipment for Non-Contact ETD Development

| Item | Function/Application | Specific Examples/Properties |

|---|---|---|

| Atmospheric Flow Tube-Mass Spectrometer (AFT-MS) | Enables sensitive detection of explosive vapors at ultra-low concentrations [1] | Capable of detecting vapors at pptv to ppqv levels; used with high-volume air sampler [1] |

| High-Volume Air Sampler | Extends standoff detection distance by increasing sample volume [1] | Flow rate of 225-240 L/min; overcomes room air currents [1] |

| SERS Substrates | Enhances Raman signals for sensitive explosive detection [2] | Noble metal nanostructures (gold, silver); enable single-molecule detection potential [2] |

| Explosive Analytical Standards | System calibration and method validation [1] [2] | RDX, nitroglycerin, TNT, PETN; available as saturated vapor sources or residue [1] |

| Ambient Ionization Sources | Enable direct analysis of samples without complex preparation [2] | Desorption electrospray ionization (DESI), dielectric barrier discharge ionization (DBDI) [2] |

Non-contact sampling technologies represent a significant advancement in explosive trace detection, addressing critical limitations of conventional contact-based methods. The integration of high-volume air sampling with sensitive detection techniques like AFT-MS enables reliable vapor detection at practical standoff distances up to 2.5 meters [1]. Emerging technologies such as SERS and ambient ionization mass spectrometry further expand the capabilities for non-contact detection with increasingly superior sensitivity and specificity [2].

Future research directions should focus on miniaturization and portability of detection systems, integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning for improved detection accuracy and reduced false positives, and development of multi-modal detection systems that combine complementary technologies for enhanced reliability [3]. Additionally, ongoing research addresses challenges in detecting explosives with particularly low vapor pressures and those deliberately concealed to evade detection [1] [2].

As global security requirements continue to evolve, non-contact sampling technologies are poised to play an increasingly vital role in protecting transportation systems, critical infrastructure, and public spaces while enabling more efficient and less intrusive security screening protocols.

Vapor pressure is a fundamental physicochemical property defined as the pressure exerted by a vapor in thermodynamic equilibrium with its condensed phases (solid or liquid) at a given temperature. For trace detection, particularly of explosives and narcotics, the saturation vapor pressure of a compound determines its equilibrium partitioning between the condensed and gas phases, directly influencing the concentration of trace vapors available for non-contact sampling [4]. Accurate prediction and measurement of vapor pressure are therefore critical for determining the theoretical detectability of target compounds and for optimizing the performance of non-contact trace detectors.

This document provides application notes and detailed experimental protocols, framed within a broader thesis on advancing non-contact sampling methods. The content is designed to equip researchers and scientists with the methodologies to quantify vapor pressure and the resulting trace vapor concentrations, which are the foundational principles upon which non-contact explosive trace detectors operate.

Fundamental Principles and Key Quantitative Data

Volatility Classification of Organic Compounds

The saturation mass concentration (C⁰) over the pure liquid is used to classify compounds into volatility ranges, which directly impacts their potential for non-contact vapor detection [4].

Table 1: Volatility Classification of Organic Compounds Based on Saturation Mass Concentration (C⁰) at 298 K

| Volatility Class | Abbreviation | Saturation Mass Concentration (C⁰) Range (µg m⁻³) |

|---|---|---|

| Extremely Low-Volatility Organic Compounds | ELVOC | < 3 × 10⁻³ |

| Low-Volatility Organic Compounds | LVOC | 3 × 10⁻³ to 3 × 10⁻¹ |

| Semi-Volatile Organic Compounds | SVOC | 3 × 10⁻¹ to 3 × 10² |

| Intermediate-Volatility Organic Compounds | IVOC | 3 × 10² to 3 × 10⁵ |

| Volatile Organic Compounds | VOC | > 3 × 10⁵ |

Vapor Pressure Prediction Models: Performance Comparison

Several quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) methods exist for predicting vapor pressure when experimental data are unavailable. The performance of these models varies significantly.

Table 2: Comparison of Vapor pressure (pvap) Prediction Methods at 298 K

| Model Type | Model Name | Key Input Parameters | Reported Mean Absolute Error (MAE, log-units) | Key Characteristics & Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Machine Learning (ML) | GC²NN (Specialized on SOA) | Molecular graphs & descriptors [4] | 0.37 [4] | High accuracy (R²=0.94) for specific organic compounds; requires sufficient training data. |

| Machine Learning (ML) | GC²NN (General Model) | Molecular graphs & descriptors [4] | 0.69 [4] | Broad scope, suitable for organic and inorganic compounds (R²=0.86). |

| Semi-Empirical | SIMPOL.1 | Functional group contributions [4] | - | Commonly used; limited to defined functional groups. |

| Semi-Empirical | EVAPORATION | Functional group contributions [4] | - | Commonly used; limited to defined functional groups. |

| Parameterization | Donahue et al. (2011) | Elemental composition [4] | - | Simple, based on sum formula; cannot distinguish structural isomers. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Remote Quantification of Trace Vapor Concentration-Pathlength in Plumes

1. Principle This protocol details the use of passive infrared hyperspectral imaging to estimate the concentration-pathlength product (CL) of trace analytes in a gaseous plume, a key parameter for non-contact remote sensing [5]. The method is based on Beer-Lambert's law and uses radiance differences between on-plume and off-plume pixels, requiring no prior knowledge of ground emissivity or temperature [5].

2. Equipment and Software

- Hyperspectral imager (operating in appropriate IR band).

- Synthetic image generation software (e.g., IR-SAGE code in MATLAB) for algorithm testing [5].

- Data processing software capable of performing least-squares regression.

3. Procedure Step 1: Data Acquisition and Plume Detection. Collect hyperspectral image data of the scene containing the target plume. Identify the spatial location of the plume within the image cube [5]. Step 2: Background Characterization. Select multiple "off-plume" pixels surrounding the plume to characterize the background spectral radiance, Lbkg [5]. Step 3: Radiance Modeling. For each "on-plume" pixel, model the observed radiance, Lon, which is a function of the background radiance, atmospheric transmission, and the plume's transmission properties [5]. Step 4: Concentration-Pathlength Estimation.

- a. Use the approximated radiance equation:

L_on ≈ L_bkg + (∂L/∂τ_p)|_(τ_p=1) * (τ_p - 1), where the plume transmissionτ_p = exp(-σ * C * L), andσis the absorption cross-section [5]. - b. For small absorbances, this simplifies to an additive model:

L_on ≈ L_bkg + Z * [CL], whereZis a matrix dependent on the analyte's absorption spectrum and the plume temperature [5]. - c. Solve for the concentration-pathlength product

[CL]using an Extended Least Squares (ELS) algorithm:[CL] = (Z^T Z)^{-1} Z^T (L_on - L_bkg)[5]. Step 5: Error Estimation. Calculate the error covariance of the estimate, considering both instrument noise and spectral errors from approximations in the model [5].

4. Critical Parameters

- Plume Temperature (

T_p): An accurate estimate for each on-plume pixel is critical, as errors propagate into significant quantification errors [5]. - Atmospheric Compensation: Estimates of up-welling atmospheric transmission and radiance are required but need not be perfect for reasonable estimates [5].

- Small Absorbance Assumption: The Taylor series expansion used is valid primarily for small absorbances [5].

Protocol: Predicting Vapor Pressure Using a Group Contribution-Assisted Graph Convolutional Neural Network (GC²NN)

1. Principle This protocol uses a machine learning model that combines molecular graph representations with traditional group contribution methods to accurately predict saturation vapor pressure (pvap) for organic compounds [4].

2. Data Curation

- Input: Assemble a data set of Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES) representations for compounds with experimentally measured pvap at 298 K from sources like PubChem [4].

- Curation: Remove duplicates and compounds with elements that appear infrequently (e.g., fewer than 30 occurrences) to ensure model robustness [4].

3. Model Training and Prediction

- Input Representation:

- Graph Component: Molecular structure is represented as a graph where atoms are nodes (with features like atom type) and bonds are edges (with features like bond order) [4].

- Group Contribution Component: Numerical molecular descriptors (e.g., molar mass) are processed in a separate, shallow neural network [4].

- Architecture: Use an adaptive-depth GC²NN where the number of graph convolutional layers depends on molecular size [4].

- Output: The model predicts the logarithm of the saturation vapor pressure (log pvap).

4. Validation

- Compare model predictions against a held-out test set of experimental data.

- Performance metrics such as Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and R² value should be reported [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for Vapor Pressure and Trace Detection Research

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Hyperspectral Imager | Core instrument for remote, non-contact detection and quantification of vapor plumes. Measures radiance across numerous spectral bands to identify and quantify analytes [5]. |

| Non-Radioactive Ion Mobility Spectrometer (e.g., IONSCAN 600) | Portable detector for lab or field validation. Uses Ion Mobility Spectrometry (IMS) to detect and identify trace particles of explosives and narcotics collected on swabs, providing ground-truth data [6]. |

| Cost-effective, Single-Use Swabs | For particle sampling from surfaces. Designed for efficient trace-particle pick-up and reduced contamination risk, compatible with IMS detectors [6]. |

| Vapor Pressure Analyzer (Portable/Benchtop) | For experimental validation of vapor pressure predictions. Directly measures the vapor pressure of liquid samples, crucial for validating computational models [7]. |

| Synthetic Hyperspectral Image Generator (e.g., IR-SAGE) | Software for generating synthetic hyperspectral images with known analyte concentrations. Used for controlled testing and validation of detection and quantification algorithms without requiring extensive field data [5]. |

| GC²NN Model Software | Machine learning tool for predicting vapor pressure from molecular structure. Provides crucial pvap estimates for novel compounds where experimental data is lacking, informing detectability limits [4]. |

Workflow and Signaling Pathway Diagrams

Remote Trace Vapor Quantification

Vapor Pressure Prediction via GC²NN

Non-Contact Detection Logical Framework

Trace explosive detection is a critical component of modern security and defense operations. The capability to detect and identify explosive materials from a distance, without physical contact, offers significant advantages for personnel safety and operational efficiency. This application note details the primary technological hurdles—sensitivity, selectivity, and environmental interference—faced by non-contact sampling methods for explosive trace detectors (ETDs). It further provides a comparative analysis of emerging technologies, detailed experimental protocols, and a research toolkit designed to advance methodological development in this field. The content is structured to support researchers, scientists, and security professionals in evaluating and implementing next-generation detection solutions.

Current Technology Landscape and Performance Metrics

The evolution of non-contact detection technologies has been marked by significant advances in sensitivity and the ability to overcome environmental challenges. The table below summarizes the key performance metrics of prominent non-contact and trace detection technologies as identified in recent literature.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Advanced Explosive Detection Technologies

| Detection Technology | Target Explosives | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Stand-off Distance | Key Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NIR Hyperspectral Imaging with CNN [8] | TNT, AN, RDX, PETN, PYX, KClO₃ | 10 mg/cm² | Remote (specified distance) | 91.08% Accuracy, 91.15% Recall, 90.17% Precision [8] |

| Fluorescence Sensing (LPCMP3) [9] | TNT (in acetone solution) | 0.03 ng/μL | N/S (Likely proximal) | Response time <5 s; Recovery <1 min [9] |

| Atmospheric Flow Tube-MS [10] | Nitroglycerin, RDX (C-4) | <10 parts per quadrillion | 2 to 8 feet | Analysis time: seconds [10] |

| Optical Microcavity Fluorescence [11] | Explosive simulants | 1 × 10^−10 M to 1×10^−15 M | N/S (Lab-based system) | Single-molecule detection in liquid phase [11] |

| Ion Mobility Spectrometry (IMS) [12] | Various (e.g., TATP, HMTD) | ppt to ppb range | Proximal (requires vapor sampling) | High miniaturization potential; used in ~15 commercial devices [12] |

Abbreviations: NIR (Near-Infrared), CNN (Convolutional Neural Network), TNT (Trinitrotoluene), AN (Ammonium Nitrate), RDX (Cyclotrimethylenetrinitramine), PETN (Pentaerythritol Tetranitrate), PYX (2,6-bis(picrylamino)-3,5-dinitropyridine), N/S (Not Specified).

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Stand-off Identification via NIR Hyperspectral Imaging and CNN

This protocol outlines the procedure for remote detection and classification of concealed explosives using a near-infrared hyperspectral imaging system coupled with a deep learning model [8].

1. Principle The method leverages the distinct NIR spectral signatures (900–1700 nm) of explosive materials. A convolutional neural network (CNN) is trained to recognize these signatures within hyperspectral image cubes, enabling identification even through common barriers like clothing, plastic, or glass [8].

2. Materials and Equipment

- Custom NIR hyperspectral imager with a transmissive grating and lateral scanning mechanism (spectral range: 900–1700 nm).

- Target explosive compounds: Potassium chlorate (KClO₃), Ammonium nitrate (AN), TNT, RDX, PETN, PYX.

- Substrates and concealment materials: Glass plates, plastic containers, fabric (e.g., cotton).

- Computer workstation with GPU for CNN training and data processing.

- Software for hyperspectral data analysis and CNN implementation (e.g., Python with TensorFlow/PyTorch).

3. Procedure A. Sample Preparation and Data Acquisition:

- Prepare standardized samples of target explosives. The cited study successfully detected trace levels as low as 10 mg/cm² for AN and TNT [8].

- Place samples on various substrates and/or conceal them behind barriers (e.g., inside thin plastic containers, under layers of clothing).

- Use the NIR hyperspectral imager to scan the target area. The system should collect spatial and spectral information for each pixel, building a hyperspectral data cube.

B. Data Preprocessing and CNN Training:

- Extract spectral data from the hyperspectral cubes and label them according to the explosive compound.

- Preprocess the data, which may include normalization, smoothing, and dimensionality reduction.

- Design a CNN architecture suitable for spectral classification. In the referenced work, the CNN model outperformed traditional methods like SVM and KNN [8].

- Split the data into training, validation, and test sets. Train the CNN model to classify the NIR spectra of the different explosives.

C. Validation and Testing:

- Validate the trained model's performance using the test set. The model demonstrated the ability to simultaneously identify over 100 targets within a single scan [8].

- Evaluate performance metrics including accuracy, recall, precision, and F1 score.

4. Data Analysis Report the classification performance of the CNN model. The cited study achieved an accuracy of 91.08%, recall of 91.15%, precision of 90.17%, and an F1 score of 0.924 [8]. The robustness of the system should be confirmed by its performance across different concealment scenarios.

Protocol: Trace Explosive Detection Using a Fluorescence Sensor and Similarity Analysis

This protocol describes a method for highly sensitive detection of TNT in solution using a fluorescent film and time-series similarity measures for classification [9].

1. Principle A fluorescent sensing material (LPCMP3) undergoes fluorescence quenching upon interaction with TNT molecules due to photoinduced electron transfer (PET). The kinetics of this quenching process are recorded as a time series, and similarity measures are used to classify the results with high specificity [9].

2. Materials and Equipment

- Fluorescent sensing material LPCMP3.

- Quartz wafers.

- Spin coater (e.g., TC-218 model).

- Tetrahydrofuran (THF) solvent.

- Micropipettes.

- UV excitation source and fluorescence detector.

- Data analysis software capable of calculating time-series similarity measures.

3. Procedure A. Fluorescent Film Fabrication:

- Dissolve 10 mg of LPCMP3 solid in 1 mL of THF and protect from light for 30 minutes.

- Pipette 20 μL of the 0.5 mg/mL solution onto a quartz wafer.

- Spin-coat the wafer at 5000 rpm for 1 minute to create a uniform fluorescent film.

- Dry the film naturally in a dust-free environment or bake in an oven at 60°C for 15 minutes [9].

B. Sensing Experiments:

- Expose the fluorescent film to TNT acetone solutions of varying concentrations (e.g., from pure acetone to 0.03 ng/μL and higher).

- Under UV excitation (max absorption ~400 nm), record the fluorescence emission (max peak ~537 nm) over time as a time-series signal.

- Test the sensor's selectivity by exposing it to common chemical reagents and other potential interferents.

- Evaluate sensor reversibility and repeatability by monitoring the recovery of fluorescence intensity after vapor exposure; the recovery response time should be less than 1 minute [9].

C. Data Classification:

- Calculate time-series similarity measures between the test results and reference patterns. The cited study successfully used a combination of the Spearman correlation coefficient and Derivative Dynamic Time Warping (DDTW) distance for classification [9].

4. Data Analysis Determine the Limit of Detection (LOD), which was found to be 0.03 ng/μL for TNT acetone solution [9]. Report the sensor's response time (<5 s), recovery time, and the classification accuracy achieved through the similarity analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Successful research and development in non-contact explosive detection rely on a core set of materials and analytical tools. The following table details essential components for building experimental capabilities.

Table 2: Essential Research Toolkit for Non-Contact Explosive Detection R&D

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Description | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Sensing Material (e.g., LPCMP3) | The active element in a fluorescence-based sensor; undergoes quenching via photoinduced electron transfer upon binding nitroaromatics like TNT [9]. | Fabrication of thin-film sensors for trace TNT vapor or solution detection [9]. |

| NIR Hyperspectral Imager (900-1700 nm) | Capties spatially-resolved spectral data; penetrates common barriers like clothing and plastic to reveal the spectral signatures of concealed materials [8]. | Remote, stand-off detection and identification of multiple explosive targets in complex environments [8]. |

| Atmospheric Flow Tube | A key component for ultra-sensitive vapor detection; provides an extended path length for ionizing target molecules, dramatically enhancing detection sensitivity for low-vapor-pressure explosives [10]. | Integration with mass spectrometers for detecting explosives like RDX and nitroglycerin at parts-per-quadrillion levels from several feet away [10]. |

| Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) | A deep learning algorithm that automatically learns and identifies complex patterns in spectral or image data, outperforming traditional classification methods [8]. | Classification of NIR hyperspectral data to distinguish between different explosive compounds with high accuracy [8]. |

| Orthogonal Analytical Techniques (e.g., IMS & FTIR) | Using two or more independent detection methods on a single platform to cross-verify results, thereby enhancing detection reliability and drastically reducing false alarm rates [12]. | Deployed in commercial portable detectors to provide more robust field identification of unknown substances [12]. |

Workflow and Signaling Pathway Diagrams

Non-Contact Explosive Detection Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the generalized logical workflow for non-contact explosive detection, integrating steps from both NIR imaging and fluorescence-based methods.

Fluorescence Quenching Signaling Pathway

This diagram details the photoinduced electron transfer (PET) mechanism, which is the foundational signaling pathway for many fluorescence-based explosive sensors.

The advancements in non-contact explosive trace detection are directly addressing the core challenges of sensitivity, selectivity, and environmental interference. Technologies like NIR hyperspectral imaging with AI [8] and ultra-sensitive vapor detection using atmospheric flow tubes [10] are pushing the boundaries of what is possible in standoff detection. Similarly, the development of novel fluorescent materials and sophisticated data analysis protocols is yielding sensors with exceptional sensitivity and specificity [9]. A critical consideration for the validation of these systems is the application of robust statistical methods, such as binomial statistics, to ensure that performance metrics like Probability of Detection (Pd) are reported with appropriate confidence levels, especially when dealing with small sample sets common in trace detection trials [13].

The integration of orthogonal techniques [12] and machine learning for data analysis [8] [9] represents a powerful trend for overcoming false positives and interpreting complex signals in real-world environments. Furthermore, the establishment of standardized protocols and best practices for sample handling and analysis, as outlined in manuals from organizations like the European Network of Forensic Science Institutes, is crucial for ensuring the reliability and admissibility of results [14]. As these technologies continue to mature and transition to commercial products [10], they hold the promise of significantly enhancing security screening, forensic investigations, and public safety by providing rapid, accurate, and safe identification of explosive threats.

The reliable detection of trace explosives is a critical challenge in security and forensic science. Non-contact and minimal-contact sampling methods are highly desirable for screening people, cargo, and public spaces, as they enable rapid analysis, reduce the risk of contamination, and minimize disruption to the screening process. Within this framework, Ion Mobility Spectrometry (IMS), Mass Spectrometry (MS), Raman Spectroscopy, and Ambient Ionization Mass Spectrometry (AIMS) represent the core technological modalities. These techniques offer a balance of sensitivity, specificity, and analytical speed, making them indispensable for modern trace detection protocols. The following application notes and protocols detail the operational principles, experimental parameters, and practical implementation of these key modalities for researchers and scientists in the field.

Ion Mobility Spectrometry (IMS)

Principle and Applications

Ion Mobility Spectrometry is a rapid, sensitive trace detection technique that operates at atmospheric pressure. It separates and detects gaseous ions based on their differing mobilities in a carrier drift gas under an applied electric field. The ion's mobility is a function of its size, shape, and charge [2]. IMS has become a cornerstone in transportation security due to its compact design, low power consumption, and rapid analysis capabilities, often providing results in seconds [2]. Its applications extend to detecting drugs, chemical warfare agents, and biomedical analysis [2].

Quantitative Performance Data

Table 1: Performance Characteristics of IMS for Explosive Detection

| Parameter | Specification | Notes / Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Limit | Low picogram (pg) to nanogram (ng) range [14] | Varies by specific explosive compound |

| Analysis Speed | Sub-minute analysis [15] | Enables high-throughput screening |

| Key Advantage | High sensitivity, portability, rapid response [2] | Ideal for field-deployable systems |

| Key Challenge | Potential for false alarms from interferents [2] | Requires optimized ionization sources |

Experimental Protocol: IMS-Based Trace Detection

Title: Standard Operating Procedure for IMS Analysis of Trace Explosives on a Swab. Objective: To qualitatively and quantitatively detect trace explosive residues collected on a sampling swab. Materials:

- IMS-based Explosive Trace Detector (e.g., products from Smiths Detection, Bruker)

- Manufacturer-specific sampling swabs

- Certified calibration standard (e.g., TNT at 5 ng/µL in acetone)

- Disposable gloves

Procedure:

- Instrument Preparation: Power on the IMS instrument and allow it to complete its startup and self-check cycle. Ensure the instrument has been recently calibrated according to the manufacturer's guidelines [16].

- Sample Collection: Wearing gloves, vigorously wipe the surface of interest with a clean sampling swab using a standardized pressure and pattern.

- Sample Introduction: Insert the swab into the heated inlet port of the IMS instrument. The instrument will automatically thermally desorb the sample, vaporizing the explosive particles for analysis.

- Analysis Initiation: Initiate the analysis cycle. The instrument will draw the vaporized sample into the ionization region.

- Ionization: The sample molecules are ionized, commonly using a radioactive source (e.g., ⁶³Ni or ²⁴¹Am) or non-radioactive alternatives like Corona Discharge (CD) or Dielectric Barrier Discharge (DBD) [2] [16].

- Separation & Detection: Ions are pulsed into a drift tube filled with a buffer gas and are separated based on their ion mobility. The drift time is measured and converted into a characteristic spectrum.

- Data Interpretation: The software compares the detected ion peak(s) and their drift times against a built-in library of explosive standards. An alarm is triggered if a match exceeds a pre-defined threshold [16].

Workflow Diagram: IMS Operation

IMS Operational Workflow: The process begins with sample collection, followed by thermal desorption of particles into vapor. The vaporized molecules are ionized, and the resulting ions are separated by their mobility in a drift tube before detection and analysis.

Mass Spectrometry (MS) and Gas Chromatography-MS (GC-MS)

Principle and Applications

Mass spectrometry remains one of the most effective techniques for detecting explosives, providing precise molecular identification and rapid analysis. MS identifies compounds by measuring the mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) of gas-phase ions. It is frequently paired with upstream separation techniques, such as Gas Chromatography (GC-MS), to isolate compounds from complex mixtures before detailed analysis [2]. GC separates components based on their interactions with a stationary phase, while MS provides the unique fragmentation pattern that serves as a molecular fingerprint [2].

Quantitative Performance Data

Table 2: Performance Characteristics of MS and GC-MS for Explosive Detection

| Parameter | Specification | Notes / Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Limit | Picogram (pg) to nanogram (ng) range [14] | High sensitivity for trace levels |

| Identification Power | High (molecular fingerprint) [2] | Fragmentation pattern enables definitive ID |

| Key Advantage | High specificity and precision [16] | Gold standard for confirmation |

| Key Challenge | Instrument size, cost, and operational complexity [2] | Often laboratory-based, though portable systems exist |

Experimental Protocol: GC-MS Analysis of Explosive Residues

Title: Protocol for GC-MS Analysis of Explosives in a Liquid Extract. Objective: To separate, identify, and confirm the presence of explosive compounds in a solvent extract from a collected sample. Materials:

- Gas Chromatograph coupled to a Mass Spectrometer

- Analytical column (e.g., DB-5MS or equivalent)

- High-purity solvent (e.g., acetone, methanol)

- Certified standard mixtures of explosives (e.g., TNT, RDX, PETN)

- Microsyringes and autosampler vials

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Extract the sampling swab or filter in a known volume of suitable solvent (e.g., 1 mL of acetone) in an autosampler vial.

- GC-MS Setup: Set the GC temperature program. A typical method may be: initial hold at 60°C for 1 minute, ramp to 300°C at 20°C/min, and a final hold for 5 minutes. Set the MS source and quadrupole temperatures according to manufacturer specifications.

- Injection: A small volume of the sample extract (e.g., 1 µL) is injected into the GC inlet in splitless mode.

- Separation: The sample is vaporized in the heated inlet and carried by the inert gas through the capillary column. Compounds are separated based on their boiling point and polarity.

- Ionization: Eluting compounds enter the MS ion source, where they are ionized, typically by Electron Impact (EI) or Chemical Ionization (CI). EI causes extensive fragmentation, providing characteristic spectra.

- Mass Analysis: Ions are separated by the mass analyzer (e.g., Quadrupole, Time-of-Flight) and detected.

- Data Analysis: The data system generates a total ion chromatogram (TIC) and mass spectra for each peak. Identification is achieved by comparing the retention time and mass spectrum of the sample component with those of a certified standard analyzed under identical conditions [2].

Raman Spectroscopy

Principle and Applications

Raman spectroscopy is a powerful, non-destructive technique that provides a molecular fingerprint based on inelastic light scattering. When monochromatic laser light interacts with a molecule, the energy shift (Raman shift) of the scattered light corresponds to the vibrational modes of the chemical bonds [17]. It is particularly effective for identifying solid, liquid, or powder explosives with high specificity [2]. Variants like Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) and Spatially Offset Raman Spectroscopy (SORS) have been developed to enhance sensitivity and allow for the detection of concealed substances [2].

Quantitative Performance Data

Table 3: Performance Characteristics of Raman Spectroscopy for Explosive Detection

| Parameter | Specification | Notes / Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Limit | Microgram (µg) range; nanogram (ng) with SERS [14] | SERS dramatically boosts sensitivity |

| Key Advantage | Non-destructive, fingerprinting, minimal sample prep [2] | Can be used for standoff detection |

| Key Challenge | Fluorescence interference, weak inherent signal [2] | SERS and other advanced techniques mitigate this |

Experimental Protocol: Raman Spectroscopy for Explosive Identification

Title: Procedure for Standoff Raman Measurement of a Suspicious Powder. Objective: To identify an unknown solid material using its Raman spectral fingerprint from a distance. Materials:

- Raman spectrometer (with a pulsed laser for standoff capability)

- Optional: SERS substrate (e.g., gold or silver nanoparticles on a slide)

- White light source for sample visualization

- Safety equipment for remote operation

Procedure:

- Instrument Setup: Power on the Raman spectrometer and laser. For standoff detection, align the pulsed laser and the telescope or collection optics towards the target sample based on the standoff distance. Synchronize the intensifier-charge coupled device (ICCD) with the optical pulse [2].

- Focusing: Use the instrument's camera to focus the laser spot onto the area of interest.

- Spectral Acquisition: Set the laser power, integration time, and number of accumulations. Initiate the measurement. The laser excites the sample, and the scattered Raman light is collected and directed to a spectrograph.

- Data Processing: The software processes the signal to generate a plot of intensity versus Raman shift (cm⁻¹). Perform baseline correction and smoothing if necessary.

- Identification: Compare the acquired spectrum against a library of reference spectra for known explosives. Key identifying peaks for explosives often fall in the region dominated by nitro-group (NO₂) symmetric and asymmetric stretches [18]. A match score above a set threshold indicates identification.

Ambient Ionization Mass Spectrometry (AIMS)

Principle and Applications

Ambient Ionization Mass Spectrometry is a rapidly developing field that enables direct analysis of samples in their native environment with minimal or no preparation. These methods allow for fast, high-throughput examination, making them ideal for field applications [2]. Several AIMS techniques, including Desorption Electrospray Ionization (DESI) and Direct Analysis in Real Time (DART), have been developed for explosive detection [2]. They work by creating ions from a sample directly in the open environment and then guiding them into the mass spectrometer for analysis.

Experimental Protocol: DART-MS for Direct Surface Analysis

Title: Direct Analysis of a Surface for Explosive Traces using DART-MS. Objective: To rapidly detect trace levels of explosives on a surface without any swabbing or solvent extraction. Materials:

- DART ion source coupled to a high-resolution mass spectrometer

- Metal or glass sampling mesh/screen

- Optional: Linear rail for automated sample presentation

Procedure:

- Instrument Setup: Turn on the DART source and set the helium gas temperature and flow rate. Typical temperatures range from 250°C to 500°C. Set the mass spectrometer to scan over the appropriate m/z range for target explosives.

- Sample Presentation: Hold the sample (e.g., a piece of baggage, fabric, or the sampling swab itself) between the DART gun outlet and the mass spectrometer inlet. Alternatively, place the sample on the sampling mesh and move it steadily through the ionization region.

- Ionization: The metastable helium atoms generated by the DART source interact with atmospheric water vapor to create reactive ion species (e.g., H₃O⁺). These ions, in turn, interact with the analyte molecules on the sample surface, desorbing and ionizing them through proton transfer or other mechanisms [2].

- Mass Analysis: The newly formed ions are drawn into the orifice of the mass spectrometer and analyzed by their mass-to-charge ratio.

- Data Interpretation: The resulting mass spectrum is examined for the presence of protonated molecules [M+H]⁺ or other adducts of the target explosives. The high mass accuracy of the spectrometer allows for confident identification based on exact mass.

Workflow Diagram: AIMS with DART

AIMS-DART Operational Workflow: The sample is directly introduced between the DART source and MS inlet. Metastable helium atoms create reagent ions from ambient air, which then desorb and ionize analyte molecules from the sample surface for mass analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Materials for Explosive Trace Detection Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Analytical Standards | Provides reference for instrument calibration and identification. | TNT, RDX, and PETN solutions at precise concentrations for GC-MS or IMS calibration [14]. |

| SERS-Active Substrates | Enhances the weak Raman signal for ultra-sensitive detection. | Gold or silver nanoparticle-coated slides for detecting nanogram levels of explosives [2]. |

| Specialized Sampling Swabs | Efficiently collects explosive particles from surfaces. | TSA-approved swabs with optimized fiber materials for IMS analysis [15]. |

| Fluorescent Sensing Polymers | Selective and sensitive recognition of nitroaromatic explosives. | LPCMP3 polymer for fluorescence quenching-based detection of TNT vapor [9]. |

| Calibration Pens | Provides a quick and consistent standard for field-checking instruments. | Pen-like device containing a certified explosive standard for IMS field calibration [16]. |

Application Notes

The field of explosive trace detection (ETD) is undergoing a significant transformation, driven by advancements in miniaturized sensor technologies and the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) for data analysis. These trends are particularly pivotal for the development of next-generation, non-contact sampling methods, enhancing both the portability and analytical precision of detection systems. The core technologies at the forefront include miniaturized spectroscopic techniques, advanced mass spectrometry, and AI-driven data processing protocols [2] [19].

The global sensor market reflects this shift, with emerging sensor technologies projected to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 17% through 2036 [20]. Concurrently, the explosive detection technology market is expected to grow from $7.76 billion in 2025 to $9.78 billion by 2029 [21]. This growth is fueled by security demands and technological innovations, with the North American ETD market specifically anticipated to reach USD 1.3 billion by 2033 [22].

Table 1: Key Miniaturized Sensing Platforms for Non-Contact ETD

| Technology | Key Principle | Advantages for Non-Contact Sampling | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) | Enhances Raman signal of molecules on nano-structured noble metal surfaces [19]. | High sensitivity, molecular fingerprinting, rapid analysis of trace particulates or vapors [2] [19]. | Single-molecule detection possible; crucial for rapid, highly sensitive, and precise detection [2]. |

| Ambient Ionization Mass Spectrometry (AIMS) | Ionizes samples in ambient conditions with minimal preparation [2]. | Direct analysis of surfaces; real-time, high-throughput examination for field applications [2]. | Enables direct analysis of samples without complex preparation, expanding applications in forensics [2]. |

| Ion Mobility Spectrometry (IMS) | Separates gaseous ions at atmospheric pressure based on mobility [2]. | Compact design, low power consumption, rapid analysis of vapor samples [2]. | Widely used in transportation security; AI integration reduces false alarms by up to 40% [15]. |

| Microwave Sensors | Measures perturbations in resonance frequency caused by sample's complex permittivity [23]. | Label-free detection; can be designed for passive vapor sensing or integrated into microfluidic channels [23]. | High sensitivity (e.g., 1.45% average sensitivity) with a small footprint (3.6 × 3.8 mm²) [23]. |

| Fluorescence Sensors | Detects fluorescence quenching or emission upon interaction with explosive molecules [9]. | High sensitivity and selectivity, fast response (e.g., <5 s), and potential for portable, fiber-optic based probes [9]. | Limit of Detection (LOD) for TNT acetone solution can be as low as 0.03 ng/μL [9]. |

Table 2: Quantitative Market and Performance Data for ETD Technologies

| Category | Metric | Value / Trend |

|---|---|---|

| Market Forecast | Global Explosive Detection Technology Market (2029) [21] | USD 9.78 Billion |

| Projected CAGR for Emerging Sensor Technologies (to 2036) [20] | 17% | |

| Projected CAGR for Raman/FTIR Spectrometers in ETD [15] | 10.80% | |

| Technology Performance | AI-Enabled False Alarm Reduction in IMS [15] | Up to 40% reduction |

| LOD for Fluorescent Sensor (TNT) [9] | 0.03 ng/μL | |

| Response Time of Fluorescent Sensor [9] | < 5 seconds | |

| Operational Trends | Growth of Dual-Mode (Vapor/Particle) ETD Systems CAGR [15] | 12.41% |

| Dominant Sampling Mode (2024) [15] | Particle-swab (71.10% share) |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: AI-Enhanced SERS for Non-Contact Trace Explosive Detection

This protocol details a methodology for using miniaturized SERS substrates and AI-driven analysis to detect explosive traces without physical contact, ideal for screening packages and personal belongings [19].

1. Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for SERS-Based Detection

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Noble Metal SERS Substrate (e.g., Au or Ag nanoparticles on a solid support) | Provides the plasmonic enhancement necessary to amplify the weak Raman signal from trace analyte molecules [19]. |

| Portable Raman Spectrometer | A miniaturized spectrometer system equipped with a laser source (e.g., 785 nm) and a detector, enabling field-deployable analysis [2] [19]. |

| Nitrogen or Air Jet System | A gentle, non-contact method to direct explosive particles or vapor clouds toward the SERS-active surface for sampling [15]. |

| AI / Machine Learning Software | Pre-trained algorithms (e.g., CNNs, PCA) for processing spectral data, performing baseline correction, identifying fingerprint peaks, and classifying the explosive type [19] [24]. |

2. Procedure

System Calibration:

- Power on the portable Raman spectrometer and allow it to stabilize.

- Acquire a background spectrum from the clean SERS substrate.

- Perform a wavelength calibration using a standard reference material (e.g., silicon wafer).

Non-Contact Sample Introduction:

- Position the item to be screened (e.g., a piece of luggage) at a defined stand-off distance (e.g., 1-5 cm) from the SERS sensor head.

- Activate the nitrogen jet for a brief, controlled duration (e.g., 1-3 seconds) to dislodge and transport particulate matter towards the SERS substrate.

Spectral Acquisition:

- Immediately after sampling, irradiate the SERS substrate with the laser.

- Collect the scattered light and acquire the Raman spectrum over a defined wavenumber range (e.g., 400 - 2000 cm⁻¹).

- Set an integration time of 1-10 seconds to balance signal-to-noise ratio with analysis speed. Repeat acquisition 3-5 times for statistical robustness.

AI-Enhanced Data Analysis:

- Pre-processing: The acquired spectra are automatically pre-processed by the integrated software. This includes cosmic ray removal, background subtraction (e.g., using asymmetric least squares), and vector normalization.

- Feature Extraction & Classification: The pre-processed spectrum is fed into a pre-trained machine learning model. The model compares the spectral features against a library of explosive fingerprints (e.g., for RDX, TNT, PETN).

- Result Reporting: The system outputs a probability score for the presence of a specific explosive and alerts the operator. The entire process, from sampling to result, should be completed in under 30 seconds to be viable for real-time screening [2].

Protocol: Ambient Ionization Mass Spectrometry for Direct Surface Analysis

This protocol utilizes AIMS for the direct, non-contact analysis of explosive residues on surfaces, requiring minimal to no sample preparation [2].

1. Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for AIMS-Based Detection

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Ambient Ionization Source (e.g., DART, DESI) | Generates a plume of excited metastable species or charged droplets at atmospheric pressure to desorb and ionize analyte molecules directly from a surface [2]. |

| Portable Mass Spectrometer | A miniaturized MS system that separates and detects ions based on their mass-to-charge ratio (m/z), providing definitive molecular identification [2]. |

| High-Purity Nitrogen/Gas | Serves as the ionization and desorption gas stream for the ambient ion source. |

| Data Analysis Software with AI | Software capable of deconvoluting complex mass spectra, recognizing isotopic patterns, and using machine learning to identify explosives amidst chemical background noise [2] [15]. |

2. Procedure

System Setup and Tuning:

- Establish a constant flow of the high-purity gas to the ionization source.

- Optimize the key parameters of the ion source: temperature, gas flow rate, and applied voltage, using a standard compound for calibration.

- Tune the mass spectrometer for optimal resolution and sensitivity in the expected m/z range (e.g., 50-500 Da for common explosives).

Targeted Interrogation:

- Position the inlet of the portable mass spectrometer 0.5 - 2 cm from the surface of interest.

- Raster the ambient ionization beam (e.g., DART gas stream) across the surface area to be analyzed. The operator does not need to touch the surface.

Real-Time Mass Spectrometry:

- Ions generated from the surface are drawn into the mass spectrometer inlet.

- Acquire mass spectra in real-time with a scan rate sufficient to capture changes as the beam moves (e.g., 1-2 spectra per second).

Data Interpretation and AI-Assisted Identification:

- The software continuously analyzes the incoming mass spectral data.

- An AI algorithm scans the data for pre-defined molecular ions or fragment ions characteristic of explosives (e.g., m/z 227 for RDX, m/z 210 for PETN).

- The system provides an audible or visual alert upon a confident match, which is based on both accurate mass and the expected isotopic abundance, reducing false positives from isobaric interferences [2] [15].

Advanced Sensing Technologies and Real-World Deployment

Core-Sheath Pillar (CSP) Architectures for Ultra-Sensitive Detection

The development of non-contact sampling methods for explosive trace detectors represents a critical frontier in security and defense research. Within this field, Core-Sheath Pillar (CSP) architectures have emerged as a transformative technology that remarkably surpasses the sensitivity of biological olfaction systems. These artificial sensing structures effectively integrate the advantages of metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) and metal oxides to achieve unprecedented detection capabilities for nitro-explosives such as RDX, TNT, and TNP [25]. The pressing need for such advanced technologies is underscored by ongoing security initiatives, including the Next Generation Explosives Trace Detection (ETD) program led by the Science and Technology Directorate, which prioritizes non-contact vapor detection as a crucial capability for aviation security and other screening scenarios [26].

CSP sensors address fundamental challenges in trace explosive detection, particularly the extremely low vapor pressures exhibited by many explosive compounds at room temperature. For instance, RDX possesses a saturated vapor pressure of approximately 4.9 ppt, making conventional detection without pre-concentration virtually impossible [25] [27]. The CSP architecture overcomes this limitation through a novel materials approach that combines selective analyte concentration with enhanced sensing reactivity, enabling detection at parts-per-quadrillion (ppq) levels without the need for complex pre-concentration systems [25].

CSP Architecture and Design

The CSP architecture features a corn-dog-like structure consisting of a metal oxide core surrounded by a metal-organic framework sheath. In the pioneering implementation, vertically oriented TiO₂ pillars approximately 150 nm in diameter and 1.5 μm in length serve as the core material, while a 15-nm-thick NH₂-MIL-125 film forms the sheath [25]. This configuration creates a perfect synergistic interface that enables two critical functions: (1) the MOF sheath selectively concentrates target analyte molecules from the vapor phase, while (2) the metal oxide core provides active sites for sensing reactions and electrical signal transduction [25].

The NH₂-MIL-125 MOF sheath possesses several design advantages for explosive detection. Its crystalline microporous structure offers an exceptionally high specific surface area (1300 m²/g) containing amino groups that interact strongly with nitro-explosives [25]. This combination provides both exceptional concentration capability and molecular selectivity. The MOF sheath can concentrate nitro-explosive vapors by 10¹² times, effectively transforming trace vapor detection into a more manageable analytical problem [25].

Sensing Mechanism and Visible Light Activation

The CSP sensing mechanism operates under visible light illumination (420-790 nm) and relies on a unique photo-activated interface between the MOF sheath and metal oxide core. The NH₂-MIL-125 sheath functions as a visible-light sensitizer, significantly increasing the absorption cross-section of TiO₂ from 410 to 530 nm, which dramatically improves light-harvesting efficiency [25]. Under visible light irradiation, the perfect band-matched synergistic interface between the MOF and metal oxide enables effective generation and separation of light-excited charge carriers, producing active oxygen species essential for the sensing reaction [25].

Remarkably, CSP (TiO₂, NH₂-MIL-125) exhibits unexpected self-promoting analyte-sensing behavior at room temperature. When nitro-explosive molecules are concentrated in the MOF sheath and interact with the photo-activated interface, they induce measurable changes in the electrical properties of the material, enabling real-time detection with exceptional sensitivity and speed [25]. Without light irradiation, the sensor shows nearly no response to explosive vapors, highlighting the crucial role of the photo-activated mechanism [25].

Performance Characteristics and Quantitative Data

Sensitivity and Detection Limits

CSP architecture demonstrates extraordinary sensitivity for nitro-explosive detection, substantially outperforming existing technologies including sniffer dogs. Experimental results show a limit of detection (LOD) of approximately 0.8 ppq for RDX vapor, which is 10³ times lower than the lowest LOD achieved by sniffer dogs or any other sensing technique without analyte pre-concentration [25].

Table 1: Detection Limits for Nitro-Explosives Using CSP Architecture

| Explosive Compound | Saturated Vapor Pressure at RT | Reported CSP LOD | Performance Enhancement |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDX (Hexogen) | 4.9 ppt [25] | ~0.8 ppq [25] | 10³ times lower than sniffer dogs |

| TNT | 9.1 ppb [25] | Not specified | Exceptional selectivity demonstrated |

| TNP (2,4,6-trinitrophenol) | 0.97 ppb [25] | Not specified | Excellent discrimination against interferences |

Operational Performance Metrics

The CSP sensor achieves breakthrough performance across multiple operational parameters essential for real-world security applications. In addition to unprecedented sensitivity, the technology offers rapid response times and excellent selectivity [25].

Table 2: Operational Performance Characteristics of CSP Sensors

| Performance Parameter | Achieved Performance | Context and Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Response Time | 0.14 minutes [25] | Faster than most conventional trace detection methods |

| Selectivity | Excellent discrimination across 25 structurally similar or commonly existing interferences [25] | Critical for reducing false alarms in field applications |

| Non-Contact Detection Range | Up to 8 meters distance [25] | Enables standoff detection for operator safety |

| Minimum Detectable Amount | 5 mg RDX [25] | Surpasses current operational requirements for trace detection |

The non-contact detection capability at distances up to 8 meters is particularly significant for security applications, as it aligns with the NextGen ETD program's objective to develop solutions that "minimize the risk of operators" during security screenings [26]. This standoff detection capability addresses a critical gap in current security protocols where close contact with suspicious items poses significant risks to personnel [26].

Experimental Protocols

CSP Fabrication Methodology

The fabrication of CSP (TiO₂, NH₂-MIL-125) follows a meticulous two-step seed-assisted solvothermal process that ensures proper formation of the core-sheath architecture with its essential functional properties [25].

Materials and Reagents:

- Al₂O₃ substrates

- Titanium precursors for TiO₂ pillar growth

- BDC-NH₂ (2-aminobenzenedicarboxylate) ligand

- Titanium n-butoxide solution

- Teflon-lined autoclave

- Solvents for washing and synthesis

Step-by-Step Fabrication Protocol:

TiO₂ Pillar Growth: Vertically oriented TiO₂ pillars are grown on an Al₂O₃ substrate. The resulting pillars should have well-defined surfaces with average dimensions of approximately 150 nm diameter and 1.5 μm length [25].

Seed Layer Formation: The TiO₂ pillars are immersed in a solution of BDC-NH₂ ligand and heated. After washing, the pillars are immersed in titanium n-butoxide solution and heated again to grow NH₂-MIL-125 seeds on the TiO₂ surface [25].

MOF Sheath Development: The NH₂-MIL-125 seed-modified TiO₂ pillars are placed in a Teflon-lined autoclave containing a solution of BDC-NH₂ and titanium n-butoxide. The autoclave is maintained at 150°C for 3 days to facilitate complete growth of the MOF sheath [25].

Structure Characterization: The resulting CSP architecture should be characterized using PXRD to confirm NH₂-MIL-125 peaks at 2θ < 25°, SEM and TEM to verify the core-sheath structure with uniform ~15 nm MOF coating, and UV-vis DRS to confirm enhanced visible light absorption from 410 to 530 nm [25].

Sensing Measurement Protocol

Equipment Setup:

- Homemade characterization system with sealed quartz chamber

- Visible light source (420-790 nm)

- Electrical characterization system with electrodes

- Dry air supply for cleaning and carrier gas

- Vapor generation system for target explosives

Measurement Procedure:

Sensor Preparation: Apply silver paste on both ends of the CSP film as electrodes. Place the sensor inside the sealed quartz chamber with dry air as the cleaning and carrier gas [25].

Baseline Establishment: Under visible light irradiation, establish a stable baseline resistance in clean dry air environment.

Vapor Exposure: Introduce target nitro-explosive vapors (RDX, TNT, or TNP) at known concentrations into the chamber while maintaining visible light illumination.

Response Monitoring: Monitor electrical resistance changes in real-time. The sensor should show negligible response without light irradiation but distinct responses under visible light illumination [25].

Data Analysis: Calculate sensor response based on resistance changes. Determine response time as time to reach 90% of maximum response. Assess selectivity by testing against common interferents [25].

CSP Fabrication Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Successful implementation of CSP-based explosive detection requires specific materials with precise functional properties. The table below details essential research reagents and their roles in the sensor system.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for CSP Explosive Detection

| Material/Reagent | Function and Role | Specifications and Notes |

|---|---|---|

| NH₂-MIL-125 MOF | Sheath material for analyte concentration and selectivity | High surface area (1300 m²/g), amino functional groups for nitro-explosive interaction [25] |

| TiO₂ (Rutile phase) | Core material for charge transport and sensing signal | Single crystal pillars growing along [001] direction, visible light activation [25] |

| BDC-NH₂ ligand | Organic linker for MOF synthesis | 2-aminobenzenedicarboxylate, provides amino functionality for explosive binding [25] |

| Titanium n-butoxide | Metal precursor for MOF synthesis | Solvothermal synthesis at 150°C [25] |

| Al₂O₃ substrate | Sensor platform | Provides mechanical support for pillar growth [25] |

Comparative Analysis with Alternative Technologies

CSP architecture represents a significant advancement over existing explosive trace detection technologies. Traditional methods include ion mobility spectrometry (IMS), which is widely deployed but suffers from limitations such as false alarm rates and matrix effects [26] [28]. Canine detection, considered the historical gold standard for vapor detection, achieves LODs around hundreds of ppt but requires intensive training and has availability limitations [25] [26].

Mass spectrometry-based approaches offer high sensitivity but typically require sample pre-concentration, increasing analysis time and complexity [27]. The PNNL trace detection technology, for instance, achieves ppt to ppq level detection but operates with an atmospheric flow tube and ionization region [27]. In contrast, CSP sensors provide the advantage of direct vapor detection without pre-concentration systems.

Hyperspectral imaging (HSI) has emerged as another non-contact approach, using spectral reflectance signatures between 400-1000 nm to identify explosive traces with Support Vector Machine classification achieving 77-81% accuracy [28]. However, this method faces challenges with low average area density of explosive traces and requires sophisticated image processing algorithms [28].

CSP Sensing Mechanism

Application in Broader Research Context

The development of CSP architectures aligns perfectly with the evolving needs in non-contact explosives detection research. The NextGen ETD program emphasizes technologies that can "quickly and accurately collect and analyze samples in a variety of ways, including from direct contact with the subject, non-contact sampling via vapors, and even through barriers" [26]. CSP technology directly addresses these requirements with its demonstrated capability for non-contact vapor detection at standoff distances.

Future research directions include integration of CSP sensors into multi-technology platforms for enhanced security screening. The vision for next-generation checkpoints involves passengers moving "through a checkpoint without stopping" with "multiple types of non-intrusive, non-contact ETD screening" performed seamlessly [26]. CSP sensors could form a critical component of such integrated systems, particularly given their exceptional sensitivity to challenging low-vapor-pressure explosives like RDX.

Further development of CSP technology may focus on expanding the range of detectable explosives, improving manufacturability for commercial deployment, and enhancing durability for field use. The fundamental architecture also holds promise for adaptation to other security and environmental monitoring applications where ultra-trace vapor detection is required.

The exceptional performance of CSP sensors—with demonstrated detection limits three orders of magnitude superior to canine detection and existing sensing techniques without pre-concentration—positions this technology as a potential paradigm shift in trace explosive detection capabilities [25]. As non-contact sampling becomes increasingly prioritized in security applications, CSP architectures offer a promising pathway toward more sensitive, rapid, and operator-safe screening systems.

Ambient Ionization Mass Spectrometry (AIMS) for Direct Sample Analysis

Ambient Ionization Mass Spectrometry (AIMS) represents a revolutionary approach in analytical chemistry, enabling the direct analysis of samples in their native environment without extensive preparation. Defined as "the ionization of unprocessed or minimally modified samples in their native environment, and it typically refers to the ionization of condensed phase samples in air," AIMS techniques have transformed mass spectrometry by dramatically decreasing experimental complexity and analysis time [29]. Since the initial development of desorption electrospray ionization (DESI) and direct analysis in real time (DART) in 2004-2005, the field has expanded to include numerous innovative techniques that maintain open-air ionization conditions while providing sensitive and specific analytical capabilities [30].

The significance of AIMS is particularly evident in applications requiring rapid, on-site analysis, such as security screening for explosive traces, where traditional laboratory-based mass spectrometry with its lengthy sample preparation and separation procedures becomes impractical [31] [30]. These ambient ionization techniques have opened new possibilities for direct, non-contact sampling of complex surfaces including porous materials, fabrics, and biological tissues, making them ideally suited for explosive trace detector research where minimal sample disturbance and rapid analysis are critical operational requirements [31].

Categorization of AIMS Techniques

Ambient ionization MS techniques can be broadly categorized into three main classes based on their fundamental desorption mechanisms, with additional categories for hybrid and alternative approaches [29]:

Table 1: Fundamental Categories of Ambient Ionization Techniques

| Category | Desorption Mechanism | Representative Techniques | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liquid Extraction | Solvent extraction/desorption | DESI, nano-DESI, LMJ-SSP, PSI, EASI | Utilizes solvent to extract molecules from sample surface; primarily targets polar molecules; ESI-like ionization mechanisms [29] |

| Plasma Desorption | Plasma-based desorption | DART, LTP, DAPCI, FAPA | Employs plasma (ionized gas) for desorption/ionization; effective for various molecular polarities; minimal sample damage [29] [31] |

| Laser Ablation | Laser energy | LAESI, MALDESI, ELDI, SpiderMass | Uses laser pulses to desorb material; enables high spatial resolution; often combined with secondary ionization [29] |

| Alternative/Integrated | Varied/combined mechanisms | REIMS, MasSpec Pen, SAWN, VSSI | Incorporates multiple desorption mechanisms or novel approaches; tailored for specific applications [29] |

Figure 1: Categorization of AIMS Techniques Based on Desorption Mechanism

AIMS Techniques for Explosive Trace Detection

Low-Temperature Plasma (LTP) for Non-Contact Sampling

Low-Temperature Plasma (LTP) has emerged as a particularly promising AIMS technique for explosive trace detection due to its non-contact sampling capabilities, simple configuration, low energy consumption, and effective operation at atmospheric pressure [31]. LTP is typically generated in a dielectric barrier discharge (DBD) configuration, producing a jet of ionized molecules, radicals, high-energy photons, and electrons with kinetic energy of a few electron volts (eV) [31]. When the LTP jet interacts with a surface, these energetic particles release adsorbed species through a process similar to chemical sputtering, making it ideal for sampling non-volatile organic compounds from complex surfaces including asphalt, fabrics, and other porous materials commonly encountered in security screening scenarios [31].

The operational advantages of LTP for explosive detection include its ability to perform continuous, non-contact sampling without solvents or disposables, minimal device contamination and memory effects, and significantly reduced energy consumption compared to thermal desorption methods [31]. These characteristics address several limitations of traditional swab-based sampling followed by thermal desorption, particularly when dealing with corrugated or porous surfaces that are challenging for conventional sampling approaches [31].

Desorption Electrospray Ionization (DESI) for Surface Analysis

Desorption Electrospray Ionization (DESI) utilizes a stream of solvent droplets assisted by a nitrogen gas flow to desorb and ionize analytes directly from sample surfaces [30]. In this technique, pneumatically-assisted primary droplets contact the sample surface, extracting and mobilizing analytes to form charged secondary droplets that are transported to the mass spectrometer inlet [30]. The typical spatial resolution of DESI is approximately 200 μm, though modifications to the solvent-capillary and sampling geometry have achieved resolutions as fine as 35 μm [30].

DESI's analytical characteristics include ionization similar to electrospray ionization (ESI), with protonated species or Na+/K+ adducts typically observed in positive ion mode and deprotonated species in negative ion mode [30]. The technique is particularly valuable for security applications as it can be operated in two-dimensional (2D) mode for mass spectrometry imaging (MSI), enabling position-dependent MS profiles that can be reconstructed into detailed chemical images of sample surfaces [30].

Paper Spray Ionization for Rapid Analysis

Paper Spray Ionization (PSI) represents a simple yet effective AIMS technique where a paper substrate serves both as the sampling medium and ionization source [30]. This approach has demonstrated particular utility for therapeutic drug monitoring and has been adapted for security screening applications [30]. The simplicity of paper spray instrumentation, combined with its minimal sample volume requirements and rapid analysis capabilities, makes it suitable for field-deployable explosive detection systems where portability and ease of operation are essential considerations.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Low-Temperature Plasma (LTP) Sampling for Explosive Traces on Porous Surfaces

Principle

Low-Temperature Plasma (LTP) desorption utilizes a dielectric barrier discharge (DBD) configuration to generate a plasma jet that desorbs and ionizes non-volatile analytes from surfaces through chemical sputtering and Penning ionization mechanisms [31].

Materials and Equipment

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials for LTP Sampling

| Item | Specifications | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| LTP Probe | Quartz tube (i.d. 1.4 mm, o.d. 3 mm) with copper electrodes | Generates low-temperature plasma jet for non-contact sampling [31] |

| Carrier Gas | Helium (99.999% purity) with mass flow controller | Plasma formation and transport of desorbed analytes [31] |

| Power Supply | Plasma generator (1-15 kV, 20-50 kHz, current limit 3A) | Sustains dielectric barrier discharge for plasma generation [31] |

| IMS Analyzer | Handheld ion mobility spectrometer (e.g., Smiths Detection LCD 3.3) | Detection and identification of desorbed explosive compounds [31] |

| Calibration Compounds | Dodecylamine (>99%), nicotinamide (98%) | System verification and performance validation [31] |

Procedure

LTP Apparatus Assembly

- Construct the LTP probe using an empty quartz tube with 1.4 mm inner diameter and 3 mm outer diameter

- Wrap copper foil electrodes around the exterior of the quartz tube, positioning the wider electrode closer to the outlet as the high-voltage electrode and the other as ground

- Connect the gas flow system using helium carrier gas controlled by a mass flow controller (typical flow rate: 1-2 slpm)

- Interface the LTP probe with a plasma generator capable of providing 1-15 kV at frequencies of 20-50 kHz with a current limit of 3A [31]

System Optimization

- Position the LTP probe approximately 5-10 mm from the target surface

- Optimize the helium flow rate to maintain stable plasma formation while maximizing analyte desorption

- Adjust the high-voltage parameters to achieve consistent plasma discharge without excessive heating of the sample surface

- Validate system performance using calibration compounds (dodecylamine, nicotinamide) before analyzing unknown samples [31]

Sample Analysis

- Direct the LTP jet onto the suspected contaminated surface (asphalt, fabric, vehicle surfaces)

- Maintain the probe in continuous motion across the surface to map contamination distribution

- Operate the handheld IMS detector in continuous mode (5-second duty cycle) to monitor desorbed analytes in real-time

- Record ion mobility spectra (plasmagrams) throughout the measurement period for subsequent analysis [31]

Data Interpretation

- Compare obtained ion mobility spectra against reference standards for explosive compounds

- Identify characteristic drift times and spectral patterns associated with target explosives