Navigating Daubert: A Strategic Guide to Validating Novel Forensic Methods for Biomedical Research

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for developing and presenting novel forensic methods that meet the stringent admissibility requirements of the Daubert standard.

Navigating Daubert: A Strategic Guide to Validating Novel Forensic Methods for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for developing and presenting novel forensic methods that meet the stringent admissibility requirements of the Daubert standard. Covering foundational legal principles, methodological rigor, troubleshooting common pitfalls, and validation strategies, it synthesizes current legal trends, including the updated Federal Rule of Evidence 702, to equip scientific experts with the knowledge to bridge the gap between laboratory innovation and courtroom acceptance.

The Daubert Standard Demystified: Legal Foundations for Scientific Experts

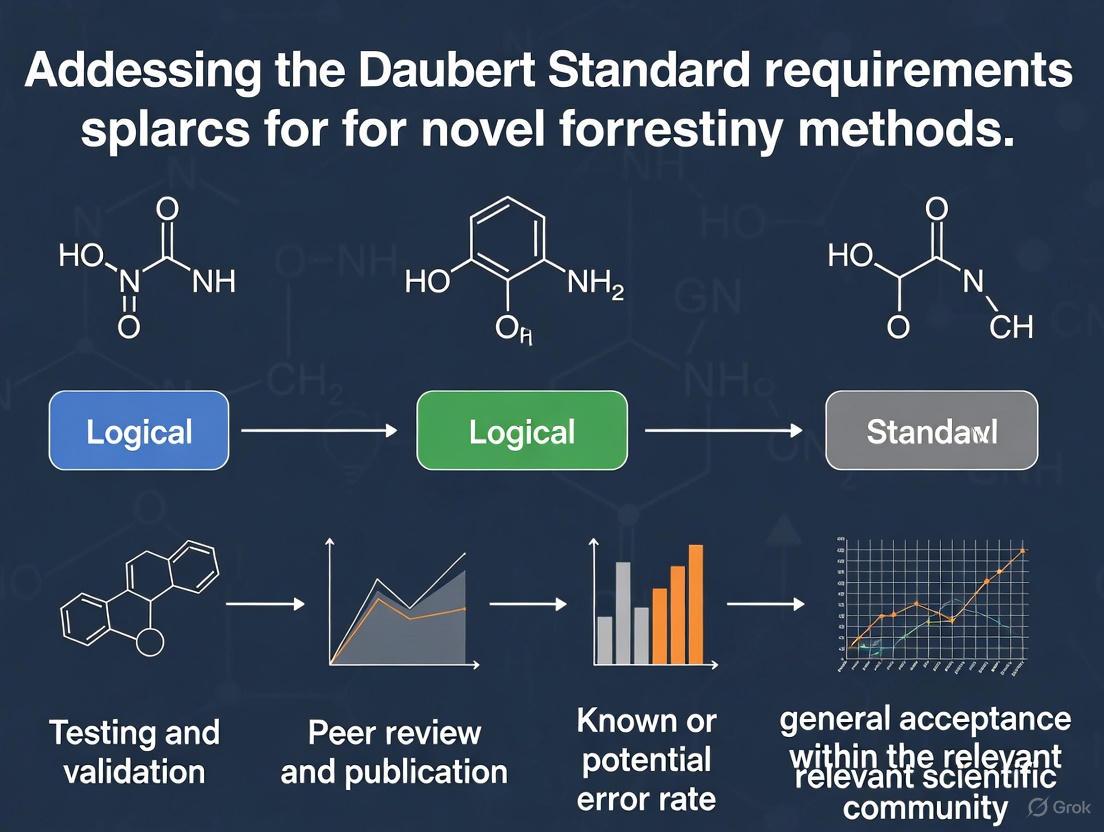

FAQs: Addressing Daubert Standard Requirements for Novel Forensic Methods

What is the fundamental difference between the Frye and Daubert standards?

The Frye Standard (from Frye v. United States, 1923) focuses on a single criterion: whether the scientific technique is "generally accepted" by the relevant scientific community [1]. The Daubert Standard (from Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc., 1993) provides a broader, multi-factor test for judges to assess the reliability and relevance of expert testimony [2] [1]. While Frye asks "Is the method generally accepted?", Daubert asks "Is the method scientifically reliable?" [3].

How did the Daubert standard evolve after the 1993 ruling?

The Daubert standard was clarified and expanded by two subsequent Supreme Court cases, often called the "Daubert Trilogy" [2]:

- General Electric Co. v. Joiner (1997): Held that appellate courts should review a trial judge's decision to admit or exclude expert testimony under an "abuse of discretion" standard [2] [3].

- Kumho Tire Co. v. Carmichael (1999): Expanded the Daubert standard to apply to all expert testimony, not just scientific testimony. This includes testimony based on technical or other specialized knowledge [2] [1].

What are the five primary factors courts consider under Daubert?

When evaluating expert testimony, judges consider these non-exhaustive factors [2] [4]:

- Testing: Whether the expert’s technique or theory can be or has been tested.

- Peer Review: Whether the technique or theory has been subjected to peer review and publication.

- Error Rate: The known or potential rate of error of the technique.

- Standards: The existence and maintenance of standards controlling the technique's operation.

- General Acceptance: Whether the technique is generally accepted in the relevant scientific community.

How does the 2023 Amendment to Federal Rule of Evidence 702 affect my research?

The December 2023 amendment to Rule 702 emphasizes that the proponent of expert testimony must demonstrate its admissibility by a "preponderance of the evidence" [5]. The key clarification was in subsection (d), which now states that "the expert’s opinion reflects a reliable application of the principles and methods to the facts of the case" [5]. For researchers, this underscores the necessity to not only develop reliable methods but also to meticulously document their reliable application to specific case facts.

What is a "Daubert Challenge" and how can I prepare for one?

A Daubert Challenge is a motion by opposing counsel to exclude an expert’s testimony on the basis that it is not reliable or relevant under Rule 702 [2]. To prepare your research and methodology:

- Ensure your techniques can be empirically tested and validated.

- Document error rates and standards controlling your methods.

- Seek peer review and publication of your underlying research.

- Be prepared to show how your opinion reflects a reliable application of your methods to the specific facts [2] [5].

Experimental Protocols for Validating Novel Forensic Methods Under Daubert

Protocol 1: Establishing Empirical Testability and Error Rates

This protocol provides a framework for validating a novel analytical method, such as the HS-FET-GC/MS technique for terpene profiling in cannabis, to satisfy Daubert's testing and error rate factors [6].

1. Objective: To demonstrate that the analytical method is based on a testable hypothesis and has a known or potential rate of error.

2. Methodology:

- Hypothesis Testing: Formulate a testable hypothesis (e.g., "This HS-FET-GC/MS method can reliably identify and quantify 45 target terpenes in cannabis plant material").

- Calibration and Linearity: Validate the method's response over a defined concentration range (e.g., 10–2000 μg/g). Establish a calibration curve for each analyte and calculate the coefficient of determination (r²) to demonstrate linearity [6].

- Accuracy and Precision: Assess intra-day and inter-day precision by repeatedly analyzing quality control samples at multiple concentrations. Report accuracy as percent bias and precision as relative standard deviation (RSD) [6].

- Analytical Limits: Determine the limit of detection (LOD) and limit of quantification (LOQ) for each analyte to define the method's operational boundaries [6].

3. Data Analysis:

- Quantify the method's error rate through rigorous validation of its accuracy (bias) and precision.

- Document all procedures, raw data, and statistical analyses to provide a transparent record of the empirical testing.

Protocol 2: Demonstrating Adherence to Standards and Peer Review

This protocol focuses on the Daubert factors of peer review, publication, and the existence of maintained standards.

1. Objective: To establish that the method has been scrutinized by the scientific community and is performed under controlled standards.

2. Methodology:

- Standards and Controls: Implement and document standard operating procedures (SOPs) for the method. This includes sample preparation, instrument operation, and data interpretation criteria [6] [7].

- Independent Verification: Submit the methodology and validation data to a peer-reviewed scientific journal for publication [6].

- Proficiency Testing: Engage in inter-laboratory comparisons or proficiency testing programs to demonstrate that the method produces consistent and reproducible results across different operators and laboratories.

3. Data Analysis:

- Maintain detailed records of all standards, controls, and SOPs.

- Upon publication, the peer review process itself serves as evidence of scientific scrutiny. The published paper becomes a citable source for the method's validity [6].

Workflow Diagram: Daubert Compliance Pathway for Novel Methods

Daubert Compliance Pathway

Table 1: Key Quantitative Metrics for Analytical Method Validation as Required by Daubert

| Validation Parameter | Target Value | Experimental Measure | Forensic Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calibration Linear Range | Defined for each analyte | Coefficient of determination (r²) | Terpene profiling: 10–2000 μg/g for 45 terpenes [6] |

| Accuracy (Bias) | Minimized and quantified | Percent bias from known value | Reported as part of method validation [6] |

| Precision | Minimized and quantified | Relative Standard Deviation (RSD) | Intra-day and inter-day precision assessed [6] |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | As low as practicable | Concentration (e.g., μg/g) | At least 6 μg/g for terpenes in cannabis [6] |

| Limit of Quantification (LOQ) | As low as practicable | Concentration (e.g., μg/g) | Defined for each analyte during validation [6] |

| Known/Potential Error Rate | Quantified and monitored | Percentage or rate | Determined through validation and proficiency testing [4] [7] |

Table 2: Daubert Factor Alignment with Documentation Requirements

| Daubert Factor | Required Documentation for Researchers | Example from HS-FET-GC/MS Method [6] |

|---|---|---|

| Empirical Testability | Detailed validation protocols, raw data, calibration curves, results from robustness testing. | Linearity tested across a defined range; accuracy and precision data reported. |

| Peer Review | Copies of published articles in reputable journals, documentation of the peer review process. | Publication in Drug Test Anal., a peer-reviewed journal. |

| Known Error Rate | Statistical analysis of accuracy/precision data, results from inter-laboratory comparisons. | Reported bias and intraday/interday precision. |

| Maintained Standards | Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs), quality control records, instrument maintenance logs. | Method validated according to forensic guidelines; use of internal standards. |

| General Acceptance | Literature reviews citing the method, adoption by other labs, presentations at scientific conferences. | Creating a tool for comprehensive profiling in forensics, implying relevance and utility. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Novel Forensic Method Development

| Item | Function / Role in Validation | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials | Provides ground truth for method calibration, accuracy determination, and quantification. | Certified terpene standards for creating calibration curves in HS-FET-GC/MS [6]. |

| Internal Standards | Corrects for analytical variability, losses during sample preparation, and instrument drift. | Retention time index mixture used in terpene analysis [6]. |

| Quality Control Samples | Monitors method performance over time, essential for establishing precision and ongoing reliability. | Prepared samples at low, mid, and high concentrations analyzed with each batch. |

| Peer-Reviewed Protocol | The documented method itself; serves as the foundational standard and is critical for peer review. | The published HS-FET-GC/MS methodology for 45 terpenes [6]. |

The Daubert Standard is the evidence rule governing the admissibility of expert witness testimony in United States federal courts and many state jurisdictions [8]. Established by the 1993 U.S. Supreme Court case Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc., it assigns trial judges the role of "gatekeepers" who must assess whether an expert's testimony is both relevant and reliable before it can be presented to a jury [9]. This standard replaced the earlier Frye standard's sole focus on "general acceptance" with a more flexible, multi-factor analysis [10].

For researchers and forensic scientists developing novel analytical methods, understanding and addressing the five Daubert factors is essential for ensuring that their techniques and expert conclusions will be admissible in court. The framework provides a systematic approach for validating new forensic methods and demonstrating their scientific rigor.

The Five Pillars: Framework for Scientific Admissibility

Testability and Falsifiability

Core Principle: The expert's methodology must be grounded in the scientific method, meaning it can be (and has been) tested and is potentially falsifiable [9] [2].

Technical Guidance for Researchers:

- Hypothesis Formulation: Clearly state the hypothesis your method is designed to test. For a novel forensic method, this might be: "Technique X can reliably distinguish between source A and source B."

- Experimental Design: Develop protocols that can produce results that could potentially prove the hypothesis false. A method that only produces confirmatory results is not scientifically valid.

- Validation Studies: Conduct studies under controlled conditions that systematically challenge the method's capabilities. Document all results, including those that may indicate limitations.

Peer Review and Publication

Core Principle: The technique or theory should have been subjected to peer review and publication, which helps identify methodological flaws and ensures the research meets disciplinary standards [9] [2].

Technical Guidance for Researchers:

- Journal Selection: Submit validation studies to reputable, peer-reviewed journals in your specific forensic discipline. Avoid "predatory" journals with minimal review standards.

- Transparency: Provide sufficient methodological detail in publications to allow for replication. Withhold only information that would genuinely compromise ongoing law enforcement operations.

- Response to Critique: Document how you have addressed reviewer comments and critiques, as this demonstrates a commitment to scientific dialogue and improvement.

Known or Potential Error Rate

Core Principle: The known or potential error rate of the technique must be established and considered [9] [2]. This is particularly challenging for many forensic disciplines, as error rate studies have often excluded inconclusive decisions, potentially understating true error rates [11].

Technical Guidance for Researchers:

- Comprehensive Error Calculation: Include all decision types (identification, exclusion, and inconclusive) in error rate calculations. An inconclusive decision on evidence that contains sufficient information for a definitive conclusion constitutes an error [11].

- Blind Proficiency Testing: Implement blind testing programs where analysts process mock evidence samples mixed into their regular workflow without their knowledge. This provides realistic performance data [12].

- Contextual Reporting: Report error rates specific to different evidence quality tiers (e.g., high-quality prints vs. partial/trace samples), as performance varies significantly with evidence difficulty.

Table: Error Rate Calculation Framework for Forensic Methods

| Decision Type | Ground Truth: Match | Ground Truth: Non-Match | Ground Truth: Inconclusive |

|---|---|---|---|

| Identification | True Positive | False Positive | Error |

| Exclusion | False Negative | True Negative | Error |

| Inconclusive | Error (if sufficient info exists) | Error (if sufficient info exists) | True Inconclusive |

Existence of Standards and Controls

Core Principle: The existence and maintenance of standards controlling the technique's operation must be evaluated [9] [2].

Technical Guidance for Researchers:

- Protocol Documentation: Develop and maintain detailed, written protocols for all analytical procedures. These should be specific enough that a trained analyst could reproduce the method.

- Quality Assurance: Implement a robust quality assurance program including equipment calibration records, reagent qualification, and environmental monitoring where appropriate.

- Certification and Training: Establish certification requirements and ongoing proficiency testing for analysts. Document all training completions and competency assessments.

General Acceptance

Core Principle: While no longer the sole determinant, general acceptance within the relevant scientific community remains an important factor [9] [10].

Technical Guidance for Researchers:

- Community Engagement: Present validation research at professional conferences and seek feedback from the broader scientific community, not just those in your immediate institution.

- Independent Validation: Encourage other laboratories to test and validate your method. Successful independent replication is strong evidence of general acceptance.

- Survey Research: For truly novel methods, consider conducting surveys of relevant scientific communities to demonstrate acceptance levels quantitatively.

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Forensic Method Validation

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function in Daubert Compliance |

|---|---|---|

| Proficiency Testing Programs | Blind testing systems, Mock evidence kits | Provides empirical data on method reliability and error rates [12] |

| Statistical Analysis Software | R, Python with scikit-learn, specialized forensic statistics packages | Enables rigorous error rate calculation and uncertainty quantification |

| Reference Materials | Certified reference materials, Standard operating procedure templates | Ensures methodological consistency and standardization across analyses |

| Documentation Systems | Electronic lab notebooks, Quality management software | Creates auditable trail of method development and validation activities |

| Peer Review Platforms | Scientific journals, Professional conference proceedings | Provides independent validation of methodological soundness [9] |

Frequently Asked Questions: Technical Troubleshooting for Daubert Compliance

Q1: Our novel forensic method has a higher error rate with low-quality samples. How should we present this in court?

A: Transparency is critical. Develop and present error rates stratified by sample quality. A method that performs well with high-quality samples but poorly with low-quality samples can still be admissible if these limitations are properly documented and disclosed. The alternative—claiming uniform reliability—can lead to exclusion and ethical concerns.

Q2: How can we address the challenge of "general acceptance" for a truly novel technique?

A: Pursue a multi-pronged strategy:

- Publish validation studies in high-quality, peer-reviewed journals

- Present your methods at professional conferences for broader exposure

- Develop training programs to allow other laboratories to adopt your methods

- Commission surveys of the relevant scientific community to quantitatively measure acceptance

Q3: Our error rate study revealed different types of errors. How should we categorize them for Daubert purposes?

A: Implement a nuanced error classification system:

Table: Forensic Decision Error Matrix

| Error Category | Definition | Impact on Reliability Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| False Positive | Incorrect association between non-matching samples | High concern - can lead to wrongful incrimination |

| False Negative | Failure to associate matching samples | Concerning - may impede justice but less dire consequences |

| Inappropriate Inconclusive | Declaring inconclusive when sufficient information exists for definitive conclusion | Moderate concern - reflects methodological uncertainty [11] |

Q4: What is the minimum sample size for establishing a statistically valid error rate?

A: There is no universal minimum, as it depends on the expected error rate and desired confidence level. However, the Houston Forensic Science Center's blind testing program provides a practical model. Use statistical power analysis during study design to determine appropriate sample sizes. Generally, several hundred tests provide more reliable estimates, particularly for detecting low-frequency errors.

Q5: How do the Daubert standards apply to non-scientific technical experts?

A: The Supreme Court's Kumho Tire decision extended Daubert's gatekeeping function to all expert testimony, including technical and experience-based expertise [8] [2]. While the factors may be applied flexibly, the fundamental requirements of reliability and relevance remain. For technical experts, focus on demonstrating standardized procedures, documentation of training and experience, and consistent application of methods.

Troubleshooting Common Daubert Challenges

| Challenge | Root Cause | Solution | Key Case/Rule Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Testimony not based on sufficient facts/data | Expert relied on unsupported assertions or data contradicted by evidence. | Ensure expert's opinion is grounded in evidence reviewed, not speculation. | EcoFactor, Inc. v. Google LLC [13] |

| Unreliable application of methods | Expert uses reliable method but applies it unreliably to case facts. | Demonstrate expert applied principles with same rigor as in professional work. | Fed. R. Evid. 702(d) [5] [14] |

| Unknown or high potential error rate | Forensic method lacks foundational validation and error rate quantification. | Conduct blind proficiency testing to establish empirical error rates. | Daubert Factor [12] |

| Judicial gatekeeping not properly exercised | Court fails to create record for admissibility decision or defers issues to jury. | Proponent must affirmatively prove admissibility by preponderance of evidence. | Fed. R. Evid. 702 (2023) [5] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the judge's "gatekeeping" role under Daubert?

Trial judges act as gatekeepers to ensure all expert testimony is not only relevant but also reliable [14]. This duty requires a preliminary assessment of whether the expert's reasoning or methodology is scientifically valid and can be properly applied to the facts at issue [9]. The gatekeeper role applies to all expert testimony, whether based on scientific, technical, or other specialized knowledge [14].

What is the difference between the Frye and Daubert standards?

The Frye Standard, from Frye v. United States, focuses on whether the scientific evidence has gained "general acceptance" in the relevant scientific community [15] [9]. The Daubert Standard, from Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc., provides a broader, more flexible set of factors for judges to assess reliability, including testing, peer review, error rates, and standards [15] [9]. While some state courts still use Frye, Daubert governs all federal courts [9].

What must the proponent of expert testimony prove after the 2023 Amendment to Rule 702?

The proponent must demonstrate by a preponderance of the evidence that the testimony satisfies all parts of Rule 702 [5] [14]. The amended rule emphasizes that the proponent's burden applies to showing that:

- The testimony is based on sufficient facts or data.

- The testimony is the product of reliable principles and methods.

- The expert's opinion reflects a reliable application of those principles and methods to the facts of the case [5].

How can a researcher establish the "known or potential error rate" for a novel forensic method?

The most effective method is through blind proficiency testing, where mock evidence samples are introduced into the ordinary workflow without analysts' knowledge [12]. This approach, pioneered by the Houston Forensic Science Center, generates empirical data on a method's performance in real-world conditions, providing the statistical foundation needed to quantify error rates [12].

What is the relationship between a court's reliability assessment and the jury's role?

The court determines whether expert testimony is reliable enough to be admitted; this is a question of admissibility [5]. The jury then decides what weight to give the admitted testimony and whether it is correct [5]. Attacks on the sufficiency of the expert's basis often become questions of weight for the jury, so long as the court finds a minimally sufficient factual basis for the opinion [5].

Experimental Protocols for Establishing Foundational Validity

Protocol for Blind Proficiency Testing

Objective: To integrate blind testing into a laboratory's quality assurance program to generate empirical data on error rates and validate forensic disciplines [12].

Methodology:

- Program Design: A dedicated quality team, separate from the analysts, designs the program. For a large laboratory, a case management system where case managers act as a buffer between requestors and analysts is a necessary predicate [12].

- Sample Creation: The team creates mock evidence samples that reflect a range of complexities and scenarios encountered in casework.

- Blind Introduction: These mock samples are submitted to the laboratory through standard channels and enter the normal workflow. Analysts have no knowledge they are being tested.

- Processing & Analysis: Analysts process the samples according to the laboratory's established protocols and issue reports.

- Data Collection: The quality team collects the results and compares them to the known "ground truth" of the mock samples.

- Data Analysis: Calculate error rates (both false positives and false negatives) and other performance metrics. The data allows for refined assessments for evidence of various difficulty levels [12].

Challenges and Solutions:

- Cost: The Houston Forensic Science Center established its program without a substantial budget increase by leveraging existing resources [12].

- Implementation: Smaller labs may struggle without a dedicated quality division. A potential solution is regional collaboration or making blind testing a feature of accreditation programs [12].

The Admissibility Pathway for Novel Scientific Evidence

The following diagram visualizes the judicial gatekeeping process a trial judge employs when determining the admissibility of expert testimony under the Daubert standard and Federal Rule of Evidence 702.

Research Reagent Solutions: A Toolkit for Daubert Compliance

| Essential Material/Data | Function in Validating Novel Methods |

|---|---|

| Blind Proficiency Test Samples | Generates empirical data on error rates under real-world laboratory conditions; essential for demonstrating foundational validity [12]. |

| Validation Study Literature | Peer-reviewed publications demonstrating the scientific validity and reliability of the underlying principles and methods [9] [14]. |

| Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) | Documents the existence and maintenance of standards and controls governing the method's operation [9] [14]. |

| Proficiency Test Results | Provides evidence of the laboratory's and individual analyst's competency in applying the method correctly ("validity as applied") [12]. |

| Data on Known/Potential Error Rate | Quantifies the uncertainty of the method's results; a key Daubert factor that courts must consider [9] [12]. |

| Documented Licenses & Agreements | Provides an objective, sufficient factual basis for an expert's opinions, particularly in damages calculations, preventing exclusion for speculation [13]. |

For researchers and scientists developing novel forensic methods, the admissibility of expert testimony in court is a critical final step in the translational research pathway. The Daubert standard, established by the Supreme Court in 1993, requires trial judges to act as "gatekeepers" to ensure that all expert testimony is not only relevant but also reliable [14] [8]. This standard applies to scientific, technical, and other specialized knowledge, encompassing the very types of novel forensic methods developed in research settings [2].

The recent December 1, 2023, amendment to Federal Rule of Evidence 702 clarifies and emphasizes two foundational requirements for proponents of expert testimony [16] [17]:

- The proponent must demonstrate to the court that it is more likely than not (the preponderance of the evidence standard) that the admissibility requirements are met.

- The expert's opinion must reflect a reliable application of principles and methods to the facts of the case [16].

For the scientific community, this amendment reinforces the necessity of building a robust, well-documented foundation for any novel method long before it reaches the courtroom. This guide provides a technical framework to troubleshoot your research and validation processes against these legal requirements.

FAQs: Addressing Core Methodological Requirements

What is the practical significance of the "preponderance of the evidence" burden clarification?

The amendment explicitly places the burden of proof on the proponent of the expert testimony (typically the party offering the expert) to demonstrate admissibility by a preponderance of the evidence [16] [17]. This is not a new standard, but a clarification aimed at correcting misapplication by some courts that had treated insufficient factual bases or unreliable applications of methodology as "weight" issues for the jury, rather than admissibility issues for the judge [17].

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Problem: A judge excludes your expert testimony because your validation study had a small sample size, and you argued this was a question of "weight" for the jury to consider.

- Solution: The court must now find it more likely than not that your testimony is "based on sufficient facts or data" before it reaches the jury. Ensure your research design and validation studies are statistically powered to meet this threshold of sufficiency at the admissibility stage.

How does the change from "the expert has reliably applied" to "the expert’s opinion reflects a reliable application" affect my research?

This wording change emphasizes objective reliability over subjective assurance [16] [17]. It is no longer sufficient for an expert to state that they reliably applied a method. The final opinion itself must be shown to be the product of that reliable application. This targets the problem of an expert using a reliable method but then offering an conclusion that extrapolates beyond what the data and method can objectively support [17].

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Problem: Your novel chemical analysis technique is reliable for identifying the presence of Substance A, but your expert's opinion states with certainty the exact time of exposure based on that presence.

- Solution: Scrutinize the chain of reasoning from your data, through your method, to your final opinion. Ensure there is a direct and validated connection at each step. Avoid overstating conclusions beyond what your methodology can support.

What are the key Daubert factors I must design my research to address?

The Daubert standard provides a non-exclusive checklist of factors for courts to consider. Your experimental design should proactively address these five core areas [14] [8] [2]:

- Empirical Testability: Whether the theory or technique can be (and has been) tested.

- Peer Review: Whether the method has been subjected to peer review and publication.

- Error Rate: The known or potential error rate of the technique.

- Standards: The existence and maintenance of standards controlling the technique's operation.

- General Acceptance: The degree to which the technique is accepted within the relevant scientific community.

Experimental Protocols for Validating Novel Forensic Methods

To withstand a Daubert challenge under the amended rule, your research and validation protocols must be meticulously documented. The following workflows provide a roadmap.

Protocol: Foundational Validation Study

This protocol outlines the core workflow for establishing the basic validity and reliability of a novel forensic method, directly addressing Daubert factors of testability, error rate, and standards.

Table: Foundational Validation Study - Key Reagents & Materials

| Research Reagent Solution | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|

| Reference Standard Materials | Provides a ground truth baseline for testing method accuracy and precision. |

| Blinded Sample Sets | Used to test the method objectively and calculate error rates without examiner bias. |

| Positive & Negative Controls | Ensures the method functions correctly in each run and can detect true negatives. |

| Calibration Instruments | Maintains measurement traceability to international standards, ensuring data integrity. |

| Statistical Analysis Software | Calculates key metrics such as false positive/negative rates, confidence intervals, and reproducibility statistics. |

Protocol: Independent Proficiency Testing

This protocol is critical for demonstrating that the method can be reliably operated by other trained examiners, strengthening claims of objectivity and general acceptance.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials for Daubert Compliance

Table: Key Reagent Solutions for Forensic Method Development & Validation

| Essential Material | Critical Function for Daubert Compliance |

|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials | Provides an objective, traceable baseline for validating the accuracy of a method, addressing "testability" and "standards." |

| Blinded Proficiency Test Kits | Allows for the objective calculation of a known error rate and assessment of examiner competence, a core Daubert factor. |

| Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) Documentation | Details the "maintenance of standards and controls" for the method, ensuring consistency and repeatability across users and labs. |

| Raw, Machine-Generated Data | Serves as the foundational "sufficient facts or data" required by Rule 702(b), allowing for independent verification of conclusions. |

| Peer-Reviewed Publication | Subjects the method to scrutiny by the broader scientific community, fulfilling the "peer review" factor and building toward "general acceptance." |

Troubleshooting Common Daubert Challenges

Even with a scientifically sound method, presentation and application issues can lead to exclusion. The following table summarizes common pitfalls and solutions in the context of the 2023 amendment.

Table: Troubleshooting Common Daubert Challenges

| Challenge Scenario | Legal & Scientific Principle | Proactive Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Stating a conclusion (e.g., "a match") with 100% certainty. | The amendment requires the opinion to reflect a reliable application. Courts view categorical claims for pattern-matching disciplines with skepticism as they may overstate what the methodology can support [15] [7]. | Use likelihood ratios or other statistical frameworks to express the strength of the evidence objectively. Train experts to communicate conclusions within the limits of the underlying data. |

| No documented, known error rate for the method. | A known or potential error rate is a key Daubert factor. Its absence makes it difficult for a court to assess reliability [2] [4]. | Conduct validation studies using blinded samples to quantify false positive and false negative rates. Publish these findings. |

| The expert's report is vague on how the method was applied to the case facts. | The proponent must show the reliable application to the case facts [16]. Vague descriptions invite challenges that the opinion is subjective. | Maintain detailed, case-specific documentation in the expert's report, explicitly linking data, the steps of the SOP, and the final opinion. |

| The method is novel and not yet "generally accepted." | "General acceptance" is only one factor and is not dispositive under Daubert. A well-validated but novel method can still be admissible [14] [8]. | Build a strong record on the other Daubert factors: testing, peer review, and error rates. Demonstrate that the method is based on sound scientific principles. |

Building a Daubert-Resilient Methodology: From Lab Bench to Courtroom

Designing Testable Hypotheses and Falsifiable Scientific Techniques

Frequently Asked Questions: Daubert & Scientific Rigor

What is the Daubert Standard, and why is it important for my research? The Daubert Standard is a rule of evidence used in U.S. federal courts to assess the admissibility of expert witness testimony. It requires that the trial judge act as a "gatekeeper" to ensure that any proffered expert testimony is both relevant and reliable [18] [8]. For researchers, especially those developing novel forensic or diagnostic methods, designing studies with Daubert in mind is crucial for ensuring that your work can withstand legal scrutiny and be utilized in court. The court looks at whether the theory or technique can be and has been tested, its error rate, and whether it has been subjected to peer review [8].

What does it mean for a hypothesis to be "falsifiable"? A hypothesis is falsifiable if it is possible to conceive of an experimental observation that could disprove it [19]. In other words, a well-designed experiment must have a possible outcome that would show the idea to be false. A hypothesis that is structured so that no experiment can ever contradict it lies outside the realm of science [20] [19].

My experiment failed. How can I systematically troubleshoot it? A structured approach to troubleshooting is key. Start by simply repeating the experiment to rule out simple human error [21]. Then, consider whether a negative result is a true failure or a valid, unexpected finding by checking the scientific literature [21]. Ensure you have the appropriate positive and negative controls to validate your experimental setup [21]. Finally, methodically change one variable at a time (e.g., antibody concentration, incubation time) to isolate the root cause, and document every change meticulously [21].

What are the different types of experimental outcomes? Experiments can be categorized based on the power of their potential outcomes [19]:

| Type | Description | Power |

|---|---|---|

| Type 1 | The experiment is designed so that a negative outcome would falsify the working hypothesis. | Most powerful |

| Type 2 | A positive result is consistent with the hypothesis, but a negative result does not invalidate it. | Less powerful / Inconclusive |

| Type 3 | The findings are consistent with your hypothesis but also with other models, providing no useful information. | Useless |

Troubleshooting Guide: Weak Signal in Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Problem: The fluorescence signal in your IHC experiment is much dimmer than expected.

Expected Workflow: The diagram below outlines the standard IHC protocol, which serves as a reference for identifying where issues may arise.

Solution: A Step-by-Step Diagnostic Path Follow this logical troubleshooting path to efficiently identify and resolve the issue.

Specific Variables to Test: If you reach Step 4, here are key variables to investigate, one by one [21]:

- Concentration of primary and secondary antibodies: The concentration may be too low.

- Fixation time: The tissue may not have been fixed long enough.

- Number of washing steps: Excess washing may have rinsed away the signal.

- Microscope light settings: The settings on the microscope may be incorrect.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials used in biochemical assays, such as the cytochrome c release assay, which is crucial for studying mitochondrial pathways in apoptosis and drug mechanisms [22].

| Reagent / Assay | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Caspase Activity Assays | Measure the activity of caspase enzymes, which are key executioners of apoptosis. Used to determine if an experimental treatment induces programmed cell death [22]. |

| Cytochrome c Release Assays | Assess the integrity of the mitochondrial membrane. Release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria into the cytoplasm is a pivotal event in the intrinsic apoptosis pathway [22]. |

| Recombinant Proteins (e.g., Bcl-2, BID) | Purified versions of pro- and anti-apoptotic proteins. Used to manipulate apoptotic pathways in vitro to establish mechanism of action [22]. |

| ELISA Kits | Used for the sensitive and quantitative detection of specific proteins (e.g., cytochrome c) in cell lysates or culture supernatants [22]. |

| Flow Cytometry Antibodies | Antibodies conjugated to fluorescent dyes enable the detection of cell surface and intracellular markers, allowing for the analysis of heterogeneous cell populations [22]. |

Core Daubert Factors for Experimental Design

To ensure your research meets the reliability criteria of the Daubert Standard, design your studies to address the following factors [18] [8]. These should be considered when drafting the methods and discussion sections of your publications.

| Daubert Factor | Application in Research Design | Quantifiable Metric (Example) |

|---|---|---|

| Testing & Falsifiability | Formulate a hypothesis that can be proven false by a conceivable experiment. | Use of positive and negative controls in every experiment. |

| Peer Review | Disseminate findings through publication in reputable scientific journals. | Number of peer-reviewed publications citing the method. |

| Error Rate | Establish the known or potential rate of error for the technique. | Statistical measures (e.g., p-values, confidence intervals, false positive/negative rates). |

| Standards & Controls | Implement and document standard operating procedures (SOPs) for the technique. | Adherence to established industry or internal SOPs; results from control experiments. |

| General Acceptance | Demonstrate that the technique is widely accepted in the relevant scientific field. | Citations by independent research groups; adoption in clinical or industry guidelines. |

Experimental Protocol: Cytochrome c Release Assay

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for a Recombinant Human Bcl-2 Cytochrome c Release Assay, a key experiment for studying the regulation of apoptosis, a critical process in drug development [22].

Objective: To test the hypothesis that recombinant human Bcl-2 protein inhibits the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria, thereby suppressing apoptosis. This hypothesis is falsifiable because the experiment can be designed to show that Bcl-2 has no significant inhibitory effect.

Materials:

- Isolation Kit for Mitochondria

- Recombinant Human Bcl-2 Protein

- Buffer for Assay

- Anti-cytochrome c Antibodies

- ELISA Kit for Cytochrome c

Methodology:

- Mitochondria Isolation: Isolate intact mitochondria from human cell lines using a standardized centrifugation protocol.

- Experimental Setup:

- Test Group: Incubate isolated mitochondria with recombinant human Bcl-2 protein.

- Positive Control: Incubate mitochondria with a known inducer of cytochrome c release (e.g., recombinant BID protein) [22].

- Negative Control: Incubate mitochondria with assay buffer only.

- Incubation: Allow the reactions to proceed for a defined period at 37°C.

- Separation: Centrifuge the samples to pellet the mitochondria.

- Quantification: Transfer the supernatant to a new tube and use a cytochrome c-specific ELISA to quantify the amount of cytochrome c released into the supernatant [22].

Interpretation & Falsifiability: The hypothesis that "Bcl-2 inhibits cytochrome c release" would be falsified if the concentration of cytochrome c in the supernatant of the Test Group is statistically indistinguishable from the Positive Control. A result supporting the hypothesis would show cytochrome c levels in the Test Group are significantly lower than the Positive Control and similar to the Negative Control.

Integrating Peer-Review and Publication into Your Development Workflow

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This technical support center provides targeted guidance for researchers integrating robust peer-review and publication strategies into their development workflows, with a specific focus on meeting the Daubert Standard for novel forensic methods. The following FAQs and troubleshooting guides address common experimental and procedural challenges.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why is peer-review integration critical for novel forensic method development? A rigorous peer-review process is a core component of the Daubert guidelines, which courts use to assess the admissibility of scientific evidence [2]. It demonstrates that your methodology has been subjected to scrutiny by the scientific community, which is one of the five Daubert factors for establishing reliability [4]. Integrating peer-review throughout development, rather than just at the end, creates a documented record of validation and refinement.

2. What are the most common Daubert challenges to novel forensic techniques? Challenges often focus on a method's scientific foundation. Common issues include [2] [4]:

- Unknown or potential error rate: The method has not undergone testing to establish its reliability and error boundaries.

- Lack of standards and controls: No standard operating procedures or controls exist to ensure the method is consistently applied.

- Insufficient peer-review: The underlying theory or technique has not been published in peer-reviewed literature.

3. How can I proactively design experiments to withstand a Daubert challenge? Design your experimental plan with the five Daubert factors in mind from the outset [2] [4]. Ensure your work includes:

- Testable Hypotheses: Frame your research around hypotheses that can be and have been tested.

- Appropriate Controls: Include positive and negative controls in your experimental design to validate results.

- Error Analysis: Quantify the error rate of your technique through repeated testing and validation studies.

- Detailed Documentation: Meticulously record all protocols, results, and deviations.

4. Our team struggles with reviewer diversity, leading to narrow feedback. How can AI assist? AI tools can systematically process large databases to identify qualified reviewers based on expertise, thereby expanding beyond familiar networks [23]. These systems can enhance reviewer diversity by identifying experts across different demographics, geographic locations, and career stages, which helps to reduce unconscious bias and provides a broader range of scientific perspectives [23].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Scenarios

Scenario 1: Unexpected Experimental Results During Validation You are developing a new assay and initial results are inconsistent or do not match expected outcomes.

| Troubleshooting Step | Actions & Considerations | Daubert Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Repeat the Experiment | Repeat unless cost/time prohibitive; check for simple human error in protocol execution [21]. | Establishes reliability and helps determine the potential error rate [2]. |

| Validate Controls | Run a positive control to confirm the experimental system is functioning correctly [21]. | Demonstrates use of standards and controls, a key Daubert factor [2]. |

| Check Reagents & Equipment | Verify storage conditions and expiration dates; inspect for contamination or degradation [21]. | Ensures the methodology is applied reliably, supporting the maintenance of standards [2]. |

| Systematically Change Variables | Alter one variable at a time (e.g., concentration, incubation time) to isolate the issue [24] [21]. | The systematic approach is a hallmark of the scientific method, showing the technique can be tested [4]. |

Scenario 2: Peer-Review Feedback Identifies a Methodological Flaw A reviewer of your submitted manuscript points out a critical flaw in your experimental design or data interpretation.

| Troubleshooting Step | Actions & Considerations | Daubert Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Objectively Evaluate the Critique | Do not become defensive. Assess whether the flaw invalidates the conclusions or can be addressed with new experiments. | Engaging with peer-review directly satisfies a primary Daubert factor [2] [4]. |

| Design a New Experiment | Develop a new experimental plan to specifically address the flaw identified by the reviewer. | This process strengthens the validity of your methodology and its error rate assessment [2]. |

| Document the Entire Process | Keep detailed records of the original critique, your planned response, and all new results [21]. | Creates a transparent audit trail showing how criticism was incorporated, bolstering methodological rigor [4]. |

| Publish the Corrected Study | Submit a revised manuscript, which may include the new data and an explanation of how the flaw was corrected. | The final published paper serves as documented evidence of peer-review and general acceptance [4]. |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following materials are critical for developing and validating robust methods.

| Reagent / Material | Function in Development & Validation |

|---|---|

| Positive Control Samples | Provides a known reference signal to verify the experimental protocol is functioning correctly on each run [21]. |

| Negative Control Samples | Identifies background signal or contamination, ensuring specific detection of the target analyte [21]. |

| Reference Standard Materials | Allows for calibration of instruments and methods, ensuring consistency and accuracy across experiments. |

| Blinded Validation Samples | Used during final validation to objectively assess the method's accuracy and error rate without experimenter bias. |

Experimental Workflow for Daubert-Compliant Method Development

The diagram below outlines a development workflow that incorporates peer-review and validation checkpoints designed to satisfy Daubert criteria.

Peer-Review Integration and Daubert Factor Mapping

The following workflow specifically illustrates how to integrate peer-review at multiple stages to directly address the five Daubert factors.

Establishing Known or Potential Error Rates and Statistical Confidence

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Error Rates and Confidence

Q1: Why are error rates and statistical confidence critical for novel forensic methods? A1: Legal standards for admitting scientific evidence, such as the Daubert Standard, require courts to consider the known or potential error rate of a technique and its application [25] [26]. Establishing these metrics is fundamental to demonstrating that a method is scientifically valid and reliable, thereby ensuring its admissibility in court [15]. Without a known error rate and a measure of statistical confidence, the reliability of a forensic method can be successfully challenged.

Q2: What is the difference between a confidence interval and a confidence level? A2: A confidence interval is the range of values within which you expect your estimate (e.g., a mean measurement) to fall if you repeat your experiment. The confidence level is the percentage of times you expect the true value to lie within that confidence interval if you were to repeat the sampling process multiple times [27]. For example, a 95% confidence level means that if you were to take 100 random samples, the true population parameter would fall within the calculated confidence interval in 95 of those samples [28].

Q3: How can I estimate an error rate for a novel method that has no historical data? A3: For novel methods, you must conduct developmental validation studies [29]. This involves designing experiments that robustly stress-test the method using representative data that challenges its limits [29]. The observed error rate from these controlled studies provides the initial, potential error rate. This process must be thoroughly documented, including the study design, data used, and the resulting error rate calculations, to satisfy legal and accreditation requirements [29] [25].

Q4: A common misinterpretation is that a 95% confidence interval means there's a 95% chance the true value is in the interval. Is this correct? A4: No, this is a common misunderstanding. The correct interpretation is that 95% of the confidence intervals calculated from many repeated random samples will contain the true population parameter [28] [27]. For any single, specific calculated interval, the true value is either in it or not; there is no probability attached to a single, realized interval [28].

Q5: What are the key legal benchmarks for scientific evidence in the United States? A5: The primary benchmarks are the Daubert Standard and Federal Rule of Evidence 702 [25] [5]. As clarified in a 2023 amendment to Rule 702, the proponent of the expert testimony must demonstrate by a preponderance of the evidence that the testimony is based on sufficient facts or data, is the product of reliable principles and methods, and that the expert has reliably applied those principles and methods to the case [5] [30]. Known or potential error rates are a key factor under Daubert [25].

Table 1: Common Critical Values for Confidence Intervals

| Confidence Level | Alpha (α) for two-tailed CI | Z Statistic (Normal Distribution) | T Statistic (approx., for n=20) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 90% | 0.10 | 1.64 | 1.73 |

| 95% | 0.05 | 1.96 | 2.09 |

| 99% | 0.01 | 2.57 | 2.86 |

Data adapted from statistical resources [27].

Table 2: Forensic Analyst Perceptions of Error Rates (Survey Data)

| Error Type | Perceived Rarity | Analyst Preference for Minimization |

|---|---|---|

| False Positive (e.g., incorrect match) | Perceived as "even more rare" than false negatives | Most analysts prefer to minimize false positive risk |

| False Negative (e.g., missing a match) | Perceived as "rare" | Less of a priority compared to false positives |

Summary of survey results from practicing forensic analysts [26].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Method Validation for a Novel Digital Forensic Technique

This protocol is aligned with the guidance from the Forensic Science Regulator [29].

1. Determination of End-User Requirements:

- Define the specific purpose of the method. What question is it meant to answer?

- Document the inputs, constraints, and desired outputs from the perspective of the investigator and the court.

2. Risk Assessment & Acceptance Criteria:

- Identify potential points of failure or error in the proposed method.

- Set quantitative acceptance criteria for the method's performance (e.g., "must correctly extract data with ≥99% accuracy on a standardized test set").

3. Validation Plan & Testing:

- Create a detailed plan for testing the method against the acceptance criteria.

- Select or create test data that is representative of real-case scenarios and includes challenges to stress-test the method [29].

- Execute the plan, running the method multiple times under varying conditions to gather performance data.

4. Data Analysis and Reporting:

- Calculate the observed error rates (false positives, false negatives) and establish statistical confidence intervals for key measurements.

- Compile a validation report that documents the entire process, the data collected, and the degree to which the method met the acceptance criteria. This report is the objective evidence of fitness for purpose [29].

Protocol 2: Calculating a Confidence Interval for a Population Mean

This protocol uses the common formula for data that is approximately normally distributed [28] [27].

1. Calculate the Point Estimate:

- Compute the sample mean (x̄). For example, the mean measurement result from 25 experimental runs.

2. Find the Critical Value:

- Choose your confidence level (e.g., 95%) and determine the corresponding alpha (α = 0.05 for two-tailed).

- Based on your sample size and distribution, find the correct critical value (e.g., z* = 1.96 for a z-distribution at 95% confidence, or a t* value from the t-distribution table for small samples).

3. Calculate the Standard Error:

- Compute the sample standard deviation (s).

- Calculate the standard error as: SE = s / √n, where n is the sample size.

4. Compute the Confidence Interval:

- Use the formula: CI = x̄ ± (z* × SE) or CI = x̄ ± (t* × SE).

- The result is the lower and upper bound of your confidence interval.

Method Validation and Statistical Workflows

Diagram 1: Method validation workflow for novel techniques.

Diagram 2: Confidence interval calculation process.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Forensic Method Validation

| Item Name | Category | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Representative Test Datasets | Data | Authentic or simulated data that mirrors real-case evidence; used to stress-test methods and establish baseline error rates [29]. |

| Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) Template | Documentation | A pre-defined framework for documenting the logical sequence of procedures, ensuring consistency and reliability during validation [29]. |

| Statistical Analysis Software (e.g., R, Python with SciPy) | Software | Used to calculate descriptive statistics, confidence intervals, and error rates from experimental validation data. |

| Accredited Reference Materials | Standards | Certified materials with known properties used to calibrate instruments and verify the accuracy of measurements within a method. |

| Validation Report Template | Documentation | A standardized format for reporting the objective evidence that a method is fit for its intended purpose, as required by accrediting bodies [29]. |

Implementing Rigorous Standards, Controls, and Operational Protocols

Troubleshooting Common Experimental & Technical Issues

Q1: Our novel assay is producing inconsistent results between different operators. What steps should we take to isolate the cause?

A: Inconsistent results often stem from procedural variations or environmental factors. Follow this structured approach to isolate the cause [31] [32]:

- Understand the Problem Fully: Have each operator document their exact protocol, including specific equipment used, reagent lot numbers, incubation timings, and environmental conditions (e.g., room temperature) [31].

- Remove Complexity and Isolate Variables: Simplify the experiment to its core components. Then, change only one variable at a time to pinpoint the source of discrepancy [31]. Key areas to test:

- Reagent Consistency: Use a single, common batch of reagents and consumables across all operators [31].

- Instrument Calibration: Verify that all instruments (pipettes, centrifuges, scanners) are properly calibrated and maintained.

- Protocol Adherence: Observe operators to ensure no unintended deviations from the written method exist.

- Sample Quality: Use a common, well-characterized sample or control material for all tests [12].

- Compare to a Baseline: If possible, compare results against a known validated method or a certified reference material to establish a baseline for expected performance [31].

Q2: How can we systematically document our troubleshooting process to satisfy rigorous scientific and legal scrutiny?

A: Meticulous documentation is critical for demonstrating the reliability of your method under standards like Daubert [15] [13]. Your records must prove that any issues were investigated and resolved using a scientifically sound approach.

- Create a Standardized Log: Document every action taken during troubleshooting, including the hypothesis, the test performed, all results (positive and negative), and the final conclusion [33].

- Record All Data: Preserve raw data, instrument printouts, and detailed observations. This provides the "sufficient facts or data" required for expert testimony [13] [5].

- Version Control Protocols: Any change to the experimental protocol must be documented in a revised, version-controlled Standard Operating Procedure (SOP). The rationale for the change must be explicitly stated, linking it to the troubleshooting investigation [34] [33].

Q3: What foundational validity measures must we establish for a novel forensic method before it can be considered for use in court?

A: Courts assess the reliability of scientific evidence by examining its foundational validity. For a novel method, you must proactively generate and document evidence addressing these core areas [15] [12]:

- Error Rate Estimation: Conduct blind proficiency testing to empirically measure the method's rate of false positives and false negatives [12]. This is a cornerstone of the Daubert standard.

- Scientific Validation: The method must be grounded in established scientific principles and tested using the scientific method. This involves publishing results in peer-reviewed literature [15] [12].

- Standardized Protocols & Controls: The method must be governed by clear, written procedures and include appropriate positive and negative controls to ensure results are reproducible and specific [34].

- Operator Proficiency: Demonstrate that trained analysts can consistently and reliably execute the method through rigorous training records and ongoing proficiency testing [33].

Foundational Validity & Error Rate Requirements for Novel Methods

The table below summarizes key quantitative and procedural benchmarks necessary to establish the foundational validity of a novel forensic method, directly addressing criteria from the Daubert standard and the PCAST report [15] [12].

| Requirement | Description | Target Benchmark / Data to Record |

|---|---|---|

| Empirical Error Rate | The rate of false positives and false negatives, determined through blind testing [12]. | Conduct studies to establish a statistically valid point estimate and confidence interval for each error type. The acceptable benchmark is discipline-specific. |

| Protocol Standardization | The existence and quality of detailed, step-by-step documented procedures [34]. | A version-controlled SOP that has been validated. All deviations must be documented and justified. |

| Within-Lab Repeatability | The precision of results when the method is repeated within the same laboratory under identical conditions. | Calculate the standard deviation or coefficient of variation for repeated measurements of a reference material. |

| Between-Lab Reproducibility | The precision of results when the method is reproduced across different laboratories. | Data from a collaborative trial or inter-laboratory study, showing consistent results across multiple sites. |

| Proficiency Testing | Ongoing, blind tests to monitor analyst and laboratory performance [12]. | A documented program with a >95% pass rate for analysts. Tests should be integrated into the normal workflow. |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) / Quantification (LOQ) | The lowest amount of analyte that can be reliably detected or quantified. | Empirically determined values specific to your assay, documented with the methodology used for determination. |

Experimental Protocol: Blind Proficiency Testing for Error Rate Estimation

This protocol is designed to integrate blind proficiency testing into your laboratory's workflow, providing the empirical data on error rates required by the Daubert standard [12].

1.0 Objective: To determine the false positive and false negative rates of a novel analytical method by introducing mock evidence samples into the routine casework flow without analysts' knowledge.

2.0 Scope: Applicable to any forensic discipline where samples can be prepared and introduced without distinguishing them from real casework (e.g., toxicology, latent prints, firearms comparison) [12].

3.0 Materials:

- Characterized reference materials or mock samples

- Standard laboratory equipment and reagents

- Case Management System (CMS)

4.0 Procedure: 4.1 Sample Preparation & Introduction:

- The quality assurance unit prepares mock samples that are forensically realistic.

- These samples are assigned a fictitious case number and submitted to the laboratory through the standard intake process by a dedicated case manager, ensuring the analysts are blinded [12]. 4.2 Analysis:

- Analysts process the blind proficiency test samples alongside genuine casework, following all standard operating procedures.

- No special handling or heightened scrutiny is applied to these samples. 4.3 Data Collection & Analysis:

- The results from the blind test are recorded in the CMS.

- The results are compared against the known ground truth.

- The number of correct results, false positives, and false negatives are tallied to calculate the observed error rates [12]. 4.4 Documentation:

- The entire process, from sample preparation to final result comparison, is documented in a final report. This report serves as direct evidence of the method's reliability and the laboratory's competency [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Provides a known, standardized material with a certified value for a specific property. Used for method validation, calibration, and quality control to ensure accuracy and traceability. |

| Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) | Mandatory, documented procedures that ensure consistency, reproducibility, and compliance with regulatory standards. They are the foundation of reliable and defensible scientific work [34]. |

| Positive & Negative Controls | Essential for verifying that an assay is functioning correctly. Positive controls confirm a positive result is detectable, while negative controls rule out contamination or non-specific signals. |

| Blind Proficiency Test Samples | Mock samples of known composition introduced into the testing workflow to objectively assess analyst and method performance without their knowledge, crucial for error rate estimation [12]. |

| Electronic Lab Notebook (ELN) | A system for recording research data and procedures digitally. Enhances data integrity, security, and traceability compared to paper notebooks, supporting robust documentation practices. |

| Quality Management System (QMS) | A formalized system that documents processes, procedures, and responsibilities for achieving quality policies and objectives. It is the overarching framework for laboratory accreditation [33]. |

Technical Support Workflow for Daubert-Compliant Methods

Path to Foundational Validity for Novel Methods

Demonstrating Reliable Application to the Specific Facts of the Case

This technical support center provides resources for researchers and scientists to ensure novel forensic methods meet the rigorous admissibility standards of the Daubert Standard. The framework established by Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc. requires that expert testimony be based on reliable methodology that is reliably applied to the facts of the case [2]. The following guides and FAQs are designed to help you document and implement your protocols in a manner that withstands this legal scrutiny.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Challenges to the Testability of Your Method

Problem: A peer review or legal challenge claims your novel forensic technique is not empirically testable or falsifiable.

Symptoms:

- The underlying principle of your method cannot be independently verified by other researchers.

- Your study design lacks controlled experiments to validate the method's core assertions.

- The methodology is described in vague terms that prevent replication.

Root Cause: The foundational theory or technique has not been, or cannot be, subjected to objective validation through testing, a key factor in the Daubert standard [2] [35].

Step-by-Step Solution:

- Formulate a Falsifiable Hypothesis: Clearly state what your method aims to prove and, crucially, what observable result would prove it false.

- Design a Controlled Experiment: Create a protocol that isolates the variable being measured. Use appropriate positive and negative controls.

- Document the Protocol for Replication: Record every detail—equipment settings, reagent lot numbers, environmental conditions, and data processing algorithms—so an independent lab can reproduce your work.

- Pre-register Your Study: Submit your hypothesis and experimental design to a repository before conducting the experiment to demonstrate commitment to scientific rigor.

- Share Raw Data and Code: Where possible, make de-identified raw data and analytical code available to allow for independent re-analysis.

Guide 2: Establishing a Known or Potential Error Rate

Problem: Your novel method lacks a defined error rate, making its reliability difficult to assess for the court.

Symptoms:

- Inability to quantify the method's accuracy or precision.

- No data exists on how the method performs with ambiguous or borderline samples.

- Challenges from opposing counsel regarding the method's potential for false positives or false negatives.

Root Cause: The methodology's performance characteristics have not been systematically evaluated against a known ground truth.

Step-by-Step Solution:

- Identify a Ground Truth Dataset: Obtain or create a set of samples where the outcome is definitively known (e.g., samples of verified origin or composition).

- Conduct a Blind Validation Study: Have analysts apply your method to the ground truth dataset without knowing the expected outcomes to prevent bias.

- Calculate Performance Metrics: Quantify the results to establish:

- False Positive Rate: The proportion of true negatives incorrectly identified as positives.

- False Negative Rate: The proportion of true positives incorrectly identified as negatives.

- Overall Accuracy: The proportion of true results (both true positive and true negative) in the population.

- Document and Report Confidence Intervals: Present error rates with their statistical confidence intervals to provide a range of reliability.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: How does the Daubert Standard differ from the older Frye Standard? A: The Frye Standard relies solely on whether a method is "generally accepted" by the relevant scientific community [35]. The Daubert Standard is broader and more flexible, making the judge a "gatekeeper" who considers testing, peer review, error rates, and standards, in addition to general acceptance [2] [35].

Q: What specific information should I include when documenting a novel method to satisfy Daubert's "reliability" factors? A: Your documentation should be comprehensive and include:

- For Testability: The initial hypothesis and all experimental protocols [2].

- For Peer Review: Copies of submitted manuscripts, reviewer comments, and publication details [2].

- For Error Rate: The full dataset and statistical analysis from your validation studies [2].

- For Standards & Controls: The standard operating procedures (SOPs) and quality control measures used in every experiment [2].

- For General Acceptance: Citations of independent studies that have used or validated your method.

Q: Our research involves proprietary algorithms. How can we demonstrate reliability without revealing intellectual property? A: While full transparency is ideal, you can:

- Use a trusted third-party auditor to validate the code and methodology without public disclosure.

- Publish detailed results from "black-box" testing, where independent researchers can input data and verify outputs without seeing the underlying algorithm.

- Disclose the algorithm's validation performance (e.g., error rates) on standard benchmark datasets.

Experimental Protocols for Key Daubert-Centric Experiments

Protocol: Blind Validation Study for Error Rate Determination

Objective: To empirically determine the false positive and false negative rates of a novel forensic identification method.

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Curate a set of at least 200 samples with a confirmed ground truth. Ensure a mix of positive and negative samples relevant to the method's application.

- Blinding: Assign a random, non-identifying code to each sample. Do not provide the ground truth information to the analysts performing the test.

- Analysis: Analysts apply the novel method according to the established SOP and record the result for each sample.

- Unblinding and Analysis: Compare the method's results against the ground truth. Calculate the performance metrics listed in the troubleshooting guide above.

Quantitative Data Summary:

| Performance Metric | Result (Example) | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|

| False Positive Rate | 2.1% | (1.0% - 3.9%) |

| False Negative Rate | 1.5% | (0.6% - 3.1%) |

| Overall Accuracy | 98.2% | (96.5% - 99.2%) |

| Number of Samples (n) | 200 | - |

Diagram: Experimental Workflow for Method Validation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Novel Method Development |

|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Provides a ground truth with known properties for calibrating instruments and validating method accuracy and precision. |

| Synthetic Controls (Positive/Negative) | Essential for establishing the method's specificity and sensitivity, and for calculating false positive/negative rates during validation. |

| High-Fidelity Enzymes/Polymerases | Critical for DNA-based methods to ensure minimal introduction of errors during amplification, supporting the reliability of the results. |

| Blocking Agents (e.g., BSA, Non-Fat Milk) | Reduces non-specific binding in assay-based methods, lowering background noise and improving the signal-to-noise ratio. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Analytes | Serves as internal standards in mass spectrometry to correct for sample loss and matrix effects, ensuring quantitative accuracy. |

Diagram: Daubert Standard Admissibility Pathway

Anticipating the Daubert Challenge: Strategies to Overcome Common Objections

A technical support center for researchers and scientists

For researchers and scientists developing novel forensic methods, the scientific soundness of your work is paramount. In the legal landscape, this soundness is formally tested by the Daubert Standard, which governs the admissibility of expert testimony in federal courts and many state jurisdictions. A core requirement of Daubert and Federal Rule of Evidence 702 is that an expert’s opinion must be the product of reliable principles and methods that have been reliably applied to the facts of the case [1].

A critical failure point in this process is the "analytical gap"—a disconnect between the data an expert relies on and the final conclusions they draw. This gap can render otherwise valid research and testimony inadmissible in court. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help you design, execute, and document your research to avoid this pitfall, ensuring your scientific work meets the rigorous demands of the legal system.

Understanding the Legal Framework: Daubert and Rule 702

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the "analytical gap"?

An "analytical gap" is a flaw in reasoning where an expert's conclusion does not logically follow from the data and methodology used. It occurs when there is an unjustified leap from the evidence to the opinion. Courts have excluded expert testimony where the expert failed to "account for . . . reasonable alternative explanations," leaving an unacceptable analytical gap between their basis and their opinions [30].

What are the key legal standards my research must satisfy?

Your work must be designed to satisfy Federal Rule of 702, which was amended in 2023 to clarify the court's gatekeeping role [5]. The rule states that expert testimony is admissible only if the proponent demonstrates to the court that it is more likely than not that [30]:

- The testimony is based on sufficient facts or data.

- The testimony is the product of reliable principles and methods.

- The expert’s opinion reflects a reliable application of those principles and methods to the case's facts.

The 2023 amendment emphasizes that the proponent of the testimony bears the burden of proving admissibility by a preponderance of the evidence and that these are threshold issues of admissibility for the judge, not just weight for the jury [5] [30].

My method is novel and not yet "generally accepted." Is it automatically inadmissible?

No. While the Frye standard relies on "general acceptance" in the relevant scientific community, the Daubert standard used in federal courts is more flexible [1]. It considers factors like:

- Whether the theory or technique can be (and has been) tested.

- Whether it has been subjected to peer review and publication.

- The known or potential error rate.

- The existence and maintenance of standards controlling the technique's operation.

- "General acceptance" is still a factor, but it is not the sole determinant [1].

Troubleshooting Guide: Bridging the Analytical Gap

This guide addresses common scenarios where analytical gaps can form and provides protocols to mitigate them.

Problem Statement: An expert draws a broad conclusion about, for instance, an industry-wide royalty rate, but relies on a small number of license agreements whose plain language contradicts the expert's interpretation [13].

Case Example: In EcoFactor, Inc. v. Google LLC, the Federal Circuit ordered a new trial on damages because an expert's testimony about a per-unit royalty rate was not based on sufficient facts or data. The court found the expert's opinion was "undoubtedly contrary to a critical fact upon which the expert relie[d]"—specifically, the language of the license agreements themselves [13].

Experimental Protocol to Avoid This Issue:

- Data Triangulation: Do not rely on a single data source. Actively seek out multiple, independent data streams that can corroborate your hypothesis.

- Documentary Audit: When relying on documents (e.g., contracts, study results, lab notes), conduct a thorough review to ensure their explicit content supports your premise. Do not rely on assumptions about what the documents say.

- Source Verification: For any factual claim that forms a basis of your opinion, verify the primary source. Avoid building conclusions on unsupported assertions or hearsay [13].

Issue 2: Failure to "Rule In" and "Rule Out" Causes

Problem Statement: In causation analysis, an expert identifies a potential cause but fails to systematically evaluate and eliminate other plausible explanations, leading to a speculative conclusion.