Logistic-Regression Calibration for Forensic Text Comparison: A Data-Driven Framework for Validating Likelihood Ratios

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and forensic professionals on the application of logistic-regression calibration in forensic text comparison (FTC).

Logistic-Regression Calibration for Forensic Text Comparison: A Data-Driven Framework for Validating Likelihood Ratios

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and forensic professionals on the application of logistic-regression calibration in forensic text comparison (FTC). It covers the foundational Likelihood Ratio (LR) framework essential for scientifically defensible evidence evaluation, details the step-by-step methodology for converting similarity scores to calibrated LRs, and addresses key challenges like data scarcity and topic mismatch. The content further explores advanced optimization techniques and underscores the critical importance of empirical validation under casework-relevant conditions, synthesizing these elements to present a robust, transparent, and legally sound approach for forensic authorship analysis.

The Likelihood Ratio Framework: A Logical Foundation for Forensic Text Comparison

Definition and Core Concept of the Likelihood Ratio

The Likelihood Ratio (LR) is a fundamental statistical measure for evaluating the strength of forensic evidence. It is defined as the ratio of two probabilities of observing the same evidence under two competing hypotheses. In the context of forensic science, these are typically the prosecution's hypothesis (Hp) and the defense's hypothesis (Hd) [1].

The formal expression of the LR is: LR = P(E|Hp) / P(E|Hd) Where:

- P(E|Hp) is the probability of observing the evidence (E) given that the prosecution's hypothesis is true

- P(E|Hd) is the probability of observing the evidence (E) given that the defense's hypothesis is true [1]

The LR provides a balanced framework for interpreting evidence, with values interpreted as follows:

- LR > 1: The evidence provides more support for Hp

- LR = 1: The evidence provides equal support for both hypotheses (neutral evidence)

- LR < 1: The evidence provides more support for Hd [1]

The LR in Forensic Text Comparison

In forensic text comparison (FTC), the LR framework is used to evaluate the strength of linguistic evidence. The application of LR in FTC requires empirical validation under conditions that replicate casework scenarios using relevant data [2]. Without proper validation that accounts for specific case conditions such as topic mismatches, the trier-of-fact may be misled in their final decision [2].

The Dirichlet-multinomial model, followed by logistic regression calibration, has been demonstrated as a viable method for calculating LRs in FTC research. This approach allows for the quantification of the strength of evidence while accounting for the complexities of textual data [2].

Quantitative Interpretation of Likelihood Ratios

The numerical value of the LR can be translated into verbal equivalents to facilitate interpretation. These verbal scales serve as guides for communicating the strength of evidence, though they should be applied with caution [1].

Table 1: Verbal Equivalents for Likelihood Ratio Values

| Strength of Evidence | Likelihood Ratio Range |

|---|---|

| Limited support | LR < 1 to 10 |

| Moderate evidence | LR 10 to 100 |

| Moderately strong evidence | LR 100 to 1000 |

| Strong evidence | LR 1000 to 10000 |

| Very strong evidence | LR > 10000 |

Calibration Protocols for Forensic Text Comparison

Experimental Setup for LR Validation

To ensure the validity of LR systems in FTC, research must replicate casework conditions using relevant data. The following protocol outlines key steps for empirical validation:

- Define Relevant Conditions: Identify textual features and conditions pertinent to the case under investigation (e.g., topic, register, style).

- Data Collection: Compile text samples that reflect these conditions, ensuring appropriate representation of both same-author and different-author scenarios.

- Model Training: Implement a Dirichlet-multinomial model to calculate initial LR values.

- Logistic Regression Calibration: Apply logistic regression to calibrate the raw LR outputs, improving their evidential reliability.

- Performance Assessment: Evaluate the calibrated LRs using the log-likelihood-ratio cost (Cllr) and visualize results with Tippett plots [2].

Critical Considerations for Meaningful LRs

For an LR to be meaningful in casework, the validation data must reflect:

- Individual Examiner Performance: Data should be representative of the particular examiner performing the analysis, as performance varies between practitioners [3].

- Case-Specific Conditions: Test materials must reflect the specific conditions of the case (e.g., text type, quality, linguistic features) [3].

- Adequate Sample Size: Sufficient same-source and different-source test trials are required for robust model training [3].

Uncertainty Assessment in Likelihood Ratios

The calculation of LRs involves subjective choices in model selection and assumptions. To address this, an uncertainty pyramid framework should be employed, exploring the range of LR values attainable under different reasonable models [4]. This is particularly critical in FTC, where methodological choices can significantly impact results.

The lattice of assumptions approach provides a structured method for assessing how different modeling decisions affect final LR values, offering transparency about the uncertainty inherent in any specific LR calculation [4].

Research Reagent Solutions for FTC Studies

Table 2: Essential Materials and Methodological Components for Forensic Text Comparison Research

| Research Component | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Dirichlet-Multinomial Model | Statistical model for calculating initial likelihood ratios from text data [2] |

| Logistic Regression Calibration | Method for calibrating raw LR outputs to improve reliability and interpretability [2] |

| Log-Likelihood-Ratio Cost (Cllr) | Performance metric for evaluating the accuracy and discrimination of a forensic evaluation system [2] [3] |

| Tippett Plots | Graphical method for visualizing the distribution of LRs for same-source and different-source comparisons [2] |

| Pool-Adjacent-Violators (PAV) Algorithm | Non-parametric algorithm used for calibrating likelihood-ratio values [5] |

| Black-Box Studies | Experimental designs where ground truth is known to researchers but not participants, used to estimate error rates [4] [3] |

Workflow Diagram for LR Calculation and Calibration

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for calculating and calibrating likelihood ratios in forensic text comparison research:

The Likelihood Ratio (LR) framework is increasingly established as the logically and legally correct method for the evaluation of forensic evidence, including that derived from text [6] [7]. An LR quantifies the strength of evidence by comparing the probability of observing the evidence under two competing hypotheses: the prosecution hypothesis (Hp) and the defense hypothesis (Hd) [6]. In the context of Forensic Text Comparison (FTC), P(E|Hp) represents the similarity component—the probability of the observed linguistic evidence if the suspect is the author. Conversely, P(E|Hd) represents the typicality component—the probability of that same evidence if some other person from a relevant population is the author [6]. The proper calibration of these LRs, often using logistic regression, is critical to ensuring that the reported strengths of evidence are reliable and meaningful for the trier-of-fact [2] [7]. This document outlines the application of these principles, with a focus on protocols for validation and calibration within FTC research.

Theoretical Foundation of Similarity and Typicality

The Likelihood Ratio Framework

The LR provides a coherent framework for updating beliefs about competing hypotheses in light of new evidence. It is formally expressed as:

In FTC, typical hypotheses are:

Hp: The suspect is the author of the questioned document.Hd: Some other person, not the suspect, is the author of the questioned document [6].

The prior odds (the fact-finder's belief before considering the linguistic evidence) is updated by the LR to yield the posterior odds, as per the odds form of Bayes' Theorem [6]. The forensic linguist's role is to calculate the LR; they are not in a position to know, and should not present, the posterior odds [6].

Operationalizing Similarity and Typicality

P(E|Hp)(Similarity): This component assesses how well the linguistic features of the questioned document align with the writing style of the suspect. A high probability indicates a high degree of similarity between the suspect's known writings and the questioned text.P(E|Hd)(Typicality): This component assesses how distinctive the observed similarity is. It evaluates how common or rare the linguistic features are in a broader, relevant population of writers. A low probability indicates that the features are unusual, thus strengthening the evidence if similarity is high [6].

The ultimate strength of the evidence depends on the combination of both components. Strong evidence is characterized by high similarity and low typicality (i.e., the features are consistent with the suspect but rare in the general population).

Experimental Protocols for LR-Based FTC

Core Protocol: System Validation with Topic Mismatch

Validation is a critical step to ensure that an FTC system provides scientifically defensible and reliable LRs. It has been argued that validation must replicate the conditions of the case under investigation using relevant data [2] [6]. The following protocol uses a mismatch in topics between known and questioned texts as a case study.

1. Objective: To empirically validate an FTC system's performance under forensically realistic conditions where the topic of the questioned document differs from the topics in the suspect's known writings.

2. Materials and Reagents:

- Text Corpora: A collection of texts from a large number of authors (e.g., 115 authors or more) [7].

- Software: Computational environment for text processing and statistical modeling (e.g., R, Python).

- Feature Extraction Tools: Scripts to extract linguistic features from raw text.

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Define Conditions. Create two experimental sets:

- Set A (Validation-focused): Designs validation experiments to reflect casework conditions. For a topic mismatch study, this involves ensuring that the known and questioned texts for a given author are on different topics [2] [6].

- Set B (Non-validation-focused): Does not control for topic mismatch, potentially using texts on the same topic for known and questioned documents [2] [6].

- Step 2: Feature Extraction. For each set of documents (known and questioned), extract quantitative linguistic features. Common features include [7]:

- N-grams: Sequences of

ncharacters or words. - Stylometric Features: Vocabulary richness, average sentence length, ratio of function words, etc.

- N-grams: Sequences of

- Step 3: Calculate Likelihood Ratios. Compute LRs using a statistical model. The Dirichlet-multinomial model is one suitable approach, followed by logistic regression calibration [2] [6].

- Step 4: Assess System Performance. Evaluate the quality of the derived LRs using:

- Log-Likelihood-Ratio Cost (

Cllr): A single metric that measures the average cost of the LRs, with lower values indicating better performance [7].Cllrcan be decomposed intoCllr_min(reflecting discriminability) andCllr_cal(reflecting calibration loss) [7]. - Tippett Plots: Visualizations that show the cumulative proportion of LRs for both same-author and different-author comparisons, allowing for an assessment of the strength and validity of the evidence across many tests [2] [7].

- Log-Likelihood-Ratio Cost (

- Step 5: Compare Results. Compare the

Cllrvalues and Tippett plots from Set A and Set B. The experiment demonstrates that Set B, which overlooks casework conditions, may yield overly optimistic or misleading performance, thus highlighting the necessity of proper validation [2] [6].

Protocol: Logistic Regression Fusion for Evidence Strength

To improve the robustness and performance of an FTC system, LRs from multiple, different procedures can be combined.

1. Objective: To fuse LRs estimated from different feature sets (e.g., multivariate features, token N-grams, character N-grams) into a single, more accurate and informative LR.

2. Procedure:

- Step 1: Generate Multiple LR Sets. Calculate LRs for the same set of comparisons using at least three different procedures (e.g., MVKD with stylometric features, token N-grams, character N-grams) [7].

- Step 2: Apply Logistic Regression Fusion. Use logistic regression to combine the LRs from the different procedures into a single, fused LR for each author comparison. This technique is robust and has been successfully applied in various forensic comparison systems [7].

- Step 3: Validate Performance. Assess the performance of the fused system using

Cllrand Tippett plots. The fused system has been demonstrated to outperform any of the single-procedure systems, particularly when the sample size of text is limited (e.g., 500-1500 tokens) [7].

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Materials and Tools for FTC Research

| Item | Function in FTC Research |

|---|---|

| Chatlog/Email Corpus | A database of authentic (e.g., predatory chatlogs) or simulated texts from multiple authors, used for developing and validating FTC systems [7]. |

| Feature Extraction Algorithms | Scripts (e.g., in Python/R) to convert raw text into quantitative features like N-grams and stylometric measurements, forming the basis for statistical modeling [7]. |

| Statistical Modeling Environment (e.g., R) | A software platform for implementing complex statistical procedures, including Dirichlet-multinomial models, logistic regression calibration, and fusion [2] [7]. |

| Validation Software/Code | Custom code or applications used to perform bootstrap validation and generate performance metrics like Cllr and calibration plots [8]. |

Data Presentation and Analysis

Quantitative Performance of FTC Systems

The following table summarizes hypothetical performance data (Cllr) for different system configurations, illustrating the impact of feature fusion and sample size, based on findings from the literature [7].

Table 2: Example Performance Metrics (Cllr) for Different FTC System Configurations Across Various Sample Sizes. Lower Cllr values indicate better performance.

| System Configuration | 500 Tokens | 1000 Tokens | 1500 Tokens | 2500 Tokens |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MVKD Procedure | 0.45 | 0.31 | 0.24 | 0.19 |

| Token N-grams Procedure | 0.52 | 0.41 | 0.35 | 0.29 |

| Character N-grams Procedure | 0.49 | 0.38 | 0.31 | 0.25 |

| Fused System | 0.35 | 0.22 | 0.15 | 0.12 |

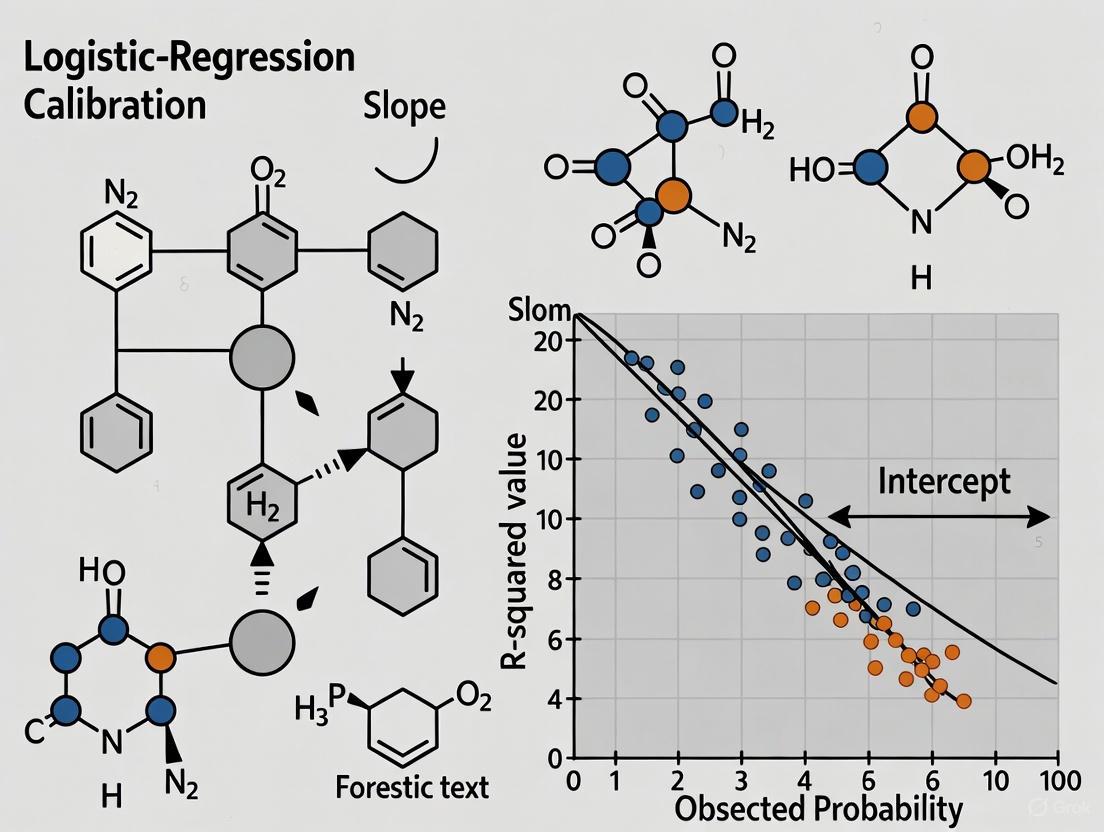

Calibration Assessment Metrics

Calibration refers to the agreement between estimated probabilities and observed outcomes. In clinical prediction models, it is vastly underreported but essential [9] [10]. The following table outlines key calibration metrics and their interpretation, which are directly applicable to assessing calibrated LRs in FTC.

Table 3: Metrics for Assessing the Calibration of a Predictive System

| Calibration Metric | Description | Target Value | Interpretation of Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calibration-in-the-large (Intercept) | Compares the average predicted risk to the overall event rate [10]. | 0 | Negative value: overestimation; Positive value: underestimation. |

| Calibration Slope | Evaluates the spread of the estimated risks [10]. | 1 | Slope < 1: predictions are too extreme; Slope > 1: predictions are too modest. |

| Flexible Calibration Curve | A graphical plot (non-linear) of predicted vs. observed event probabilities [10]. | Diagonal line | Curves below diagonal: overestimation; Curves above: underestimation. |

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

Forensic linguistics applies linguistic knowledge to legal and forensic contexts, often to determine the most likely author of a text in question. Traditional approaches have historically relied on expert subjective judgement, which can be susceptible to contextual biases and is difficult to validate objectively. This document outlines Application Notes and Protocols for implementing transparent, reproducible, and empirically validated methods, specifically through the framework of logistic-regression calibration for forensic text comparison. This shift towards a quantitative evidence evaluation framework is critical for improving the scientific rigor and admissibility of forensic text evidence in judicial processes.

Quantitative Comparison of Likelihood Ratio Estimation Methods

The core of a modern forensic text comparison involves calculating a Likelihood Ratio (LR), which quantifies the strength of the evidence under two competing propositions (e.g., the suspect is vs. is not the author of the questioned text) [11]. The following data, synthesized from empirical research, compares different methodological approaches for LR estimation.

Table 1: Empirical Comparison of Score-Based vs. Feature-Based LR Methods [12]

| Method Category | Specific Model/Function | Key Feature | Performance (Cllr) | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Score-Based | Cosine Distance | Treats entire text as a single vector; uses similarity score. | ~0.34 (Baseline) | Lower complexity analyses; initial exploratory work. |

| Feature-Based | One-Level Poisson Model | Models word counts; accounts for over-dispersion. | 0.14-0.20 improvement over baseline | General text evidence with common words. |

| One-Level Zero-Inflated Poisson Model | Accounts for frequent absence of many words in a text. | 0.14-0.20 improvement over baseline | Texts with a high number of rare or absent words. | |

| Two-Level Poisson-Gamma Model | Hierarchical model; captures variability between and within authors. | 0.14-0.20 improvement over baseline (Best overall) | Complex data; offers robust performance for formal casework. |

Table 2: Interpretation of Likelihood Ratio (LR) Values [11]

| LR Value Range | Verbal Equivalent (Support for H1 over H2) |

|---|---|

| 1 < LR ≤ 10 | Weak Support |

| 10 < LR ≤ 10² | Moderate Support |

| 10² < LR ≤ 10³ | Moderately Strong Support |

| 10³ < LR ≤ 10⁴ | Strong Support |

| 10⁴ < LR ≤ 10⁵ | Very Strong Support |

| LR > 10⁵ | Extremely Strong Support |

Experimental Protocols for Forensic Text Comparison

Protocol 1: Corpus Preparation and Feature Extraction

Objective: To construct a representative reference corpus and extract a standardized set of linguistic features for analysis.

Data Collection:

- Gather a large collection of known-author texts (e.g., from 2,157 authors, as in the cited study) [12].

- Ensure metadata (author, date, genre) is meticulously documented.

- Open Science Practice: Store all raw data in an open-access repository with a clear license to facilitate verification and replication [13].

Text Pre-processing:

- Convert all text to lowercase to ensure case-insensitive analysis.

- Remove punctuation, numbers, and other non-lexical characters.

- (Optional) Apply lemmatization or stemming to group different forms of the same word.

Feature Selection - Bag-of-Words Model:

- Create a document-term matrix that counts the occurrence of each word in each document.

- Select the n-most frequently occurring words across the entire corpus (e.g., the 400 most common words) [12]. These common words, often function words (e.g., "the," "and," "of"), are highly subconscious and thus stylistically revealing.

Protocol 2: Feature-Based LR Estimation using Poisson Models

Objective: To implement a feature-based likelihood ratio estimation system using a Two-Level Poisson-Gamma model.

Model Training:

- For each of the k selected features (e.g., 400 common words), fit a Poisson-based model to characterize an author's writing style.

- The Two-Level Poisson-Gamma model is hierarchical:

- Level 1 (Within-Author): Models the word counts for a given author as following a Poisson distribution.

- Level 2 (Between-Author): Models the variability of Poisson parameters across different authors using a Gamma distribution.

- Use the trained model to estimate the probability of observing the feature counts in the questioned text, given the author is a specific individual versus given the author is from a relevant population.

Logistic Regression Fusion and Calibration:

- The outputs (log-likelihoods) from the multiple Poisson models are used as input features for a logistic regression model [12] [11].

- This logistic regression model is trained to fuse the evidence from all features and output a well-calibrated Likelihood Ratio.

- Calibration is critical: It ensures that an LR of 100 truly represents 100 times more likely, not just a high score. Performance is evaluated using the log-likelihood ratio cost (Cllr), which separately assesses discrimination (Cllrmin) and calibration (Cllrcal) [12].

Protocol 3: Validation and Performance Evaluation

Objective: To rigorously validate the developed model and ensure its performance meets standards for forensic application.

Experimental Design:

- Use a balanced set of same-author and different-author text comparisons.

- Employ a k-fold cross-validation approach to ensure results are generalizable and not over-fitted to the training data.

Performance Metrics:

- Calculate the Cllr as the primary metric. A lower Cllr indicates a better-performing system [12].

- Analyze the Tippett plot to visualize the distribution of LRs for same-author and different-author cases.

- Report the Cllrmin (potential discrimination) and Cllrcal (calibration cost) to diagnose system performance [12].

Workflow Visualization: Transparent Forensic Text Comparison

The following diagram outlines the complete, reproducible workflow for a forensic text comparison, from data acquisition to reporting.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Computational Tools for Reproducible Forensic Linguistics

| Item Name | Type/Function | Application in Protocol | Notes for Reproducibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Text Corpus | Data | Protocol 1 | A large, relevant collection of known-author texts. Must be shared publicly or described with sufficient metadata [13]. |

| Bag-of-Words Feature Set | Data | Protocol 1, 2 | The specific list of n-most frequent words used. The value of n and the final word list must be documented. |

| Poisson-Gamma Model | Computational Algorithm | Protocol 2 | The core statistical model for capturing authorial style. Code implementation must be shared [12]. |

| Logistic Regression Calibrator | Computational Algorithm | Protocol 2 | Fuses feature outputs into a calibrated LR. Prevents "overstatement" of evidence [11]. |

| Cllr (and Cllrmin/Cllrcal) | Validation Metric | Protocol 3 | The standard for evaluating system performance. Must be reported for any developed system [12]. |

| R/Python Scripts | Software | All Protocols | Code for the entire workflow, from pre-processing to validation, must be open-source and version-controlled [13]. |

Forensic Text Comparison (FTC) involves the scientific analysis of textual evidence to address questions of authorship. A scientifically defensible approach requires a paradigm shift from subjective linguistic analysis to methods based on quantitative measurements, statistical models, and the likelihood-ratio (LR) framework, all empirically validated under casework conditions [6]. This application note details protocols for implementing such a methodology, with a specific focus on the use of logistic-regression calibration to compute LRs in the presence of complex influences from idiolect, topic, and genre. We demonstrate that rigorous validation using relevant data replicating case conditions is critical to avoid misleading the trier-of-fact [6].

The evaluation of forensic evidence comprises two core processes: analysis, the extraction of information from items of interest, and interpretation, drawing inferences about the meaning of the extracted information [14]. In FTC, traditional methods relying on human perception and subjective judgment are increasingly being replaced by a new paradigm known as Forensic Data Science. This paradigm is characterized by four key elements [6] [14]:

- The use of quantitative measurements from textual data.

- The use of statistical models for data interpretation.

- The use of the likelihood-ratio (LR) framework for evaluating the strength of evidence.

- Empirical validation of methods and systems under realistic casework conditions. This paradigm shift produces methods that are transparent, reproducible, and intrinsically resistant to cognitive bias [6]. The following sections provide detailed protocols for applying this paradigm, particularly using logistic regression, to the complex problem of textual evidence.

Core Concepts and the Likelihood-Ratio Framework

The Nature of Textual Evidence

A text is a complex datum encoding multiple layers of information, which must be disentangled in FTC [6]:

- Idiolect: An individuating way of speaking and writing, which is the target of authorship analysis [6].

- Group-Level Information: Includes author demographics (e.g., gender, age, socioeconomic background) [6].

- Communicative Situation: Encompasses genre, topic, formality, the author's emotional state, and the intended recipient, all of which can influence writing style [6].

The Likelihood Ratio Explained

The LR is a logical framework for evaluating the strength of evidence under two competing propositions [6] [15]. In the context of FTC, these are typically:

- Hp: The prosecution hypothesis (e.g., the suspect is the author of the questioned document).

- Hd: The defense hypothesis (e.g., someone other than the suspect is the author of the questioned document).

The LR is calculated as the ratio of two conditional probabilities: LR = p(E | Hp) / p(E | Hd) where E represents the quantified stylistic evidence extracted from the questioned and known documents [6] [15].

An LR > 1 supports Hp, while an LR < 1 supports Hd. The further the value is from 1, the stronger the evidence. The LR updates the prior beliefs of the trier-of-fact (judge or jury) via Bayes' Theorem [6]: Posterior Odds = Prior Odds × LR

Table 1: Interpretation of Likelihood Ratio Values

| LR Value | Verbal Equivalent (Support for Hp) |

|---|---|

| > 10⁵ | Extremely Strong |

| 10⁴ to 10⁵ | Very Strong |

| 10³ to 10⁴ | Strong |

| 10² to 10³ | Moderately Strong |

| 10¹ to 10² | Moderate |

| 1 to 10¹ | Weak |

| 1 | Inconclusive |

| Reciprocal values | Equivalent support for Hd |

Experimental Protocols for Forensic Text Comparison

Core Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the end-to-end workflow for a validated FTC study, from data collection to reporting.

Protocol 1: Data Collection and Curation for Validation

Objective: To construct a validation dataset that meets the two critical requirements of reflecting case conditions and being relevant to the case [6].

Procedure:

- Define Case Conditions: Identify the specific conditions of the case under investigation. As a case study, we focus on topic mismatch between known and questioned documents, a known challenging factor in authorship analysis [6].

- Source Relevant Data: Collect textual data from relevant populations and covering the topics of interest. For a case with topic mismatch, this requires:

- A set of known documents (K) from a candidate author on one or more specific topics.

- A questioned document (Q) on a different topic.

- A reference set of documents from a relevant population of potential authors, which includes texts on the same topic as Q and the same topic as K.

- Simulate Mismatch Conditions: For validation experiments, create two conditions:

- Matched-Topic Condition: Compare Q and K documents on the same topic.

- Mismatched-Topic Condition: Compare Q and K documents on different topics.

- Data Partitioning: Split the data into training sets (for model development) and test sets (for validation) to ensure unbiased performance evaluation.

Protocol 2: Feature Extraction and LR Calculation with a Dirichlet-Multinomial Model

Objective: To extract quantitative features from texts and compute uncalibrated likelihood ratios.

Procedure:

- Text Pre-processing:

- Clean the text (remove headers, footers, metadata).

- Apply tokenization, lowercasing, and lemmatization as required.

- Feature Selection: Extract a set of linguistic features. Common features in FTC include:

- Lexical: Character n-grams, word n-grams, function words, vocabulary richness.

- Syntactic: Punctuation marks, sentence length, part-of-speech tags.

- Structural: Paragraph length, text layout features.

- Model Training (Dirichlet-Multinomial):

- This model is a popular choice for text classification and authorship attribution as it accounts for the "burstiness" of words (the tendency for a word to appear repeatedly in a document).

- Train the model on the feature counts from the known documents of the candidate author and the reference corpus.

- Calculate Uncalibrated LR: The model outputs a score representing the probability of the evidence (the features in Q) given the author of K versus given an author from the reference population. This score is used as the uncalibrated LR.

Protocol 3: Logistic Regression Calibration

Objective: To transform the output of a statistical model (the uncalibrated LR) into a well-calibrated likelihood ratio, ensuring its validity as a measure of evidence strength [6] [14].

Rationale: Raw scores from models like the Dirichlet-multinomial are often not well-calibrated. Logistic regression is a powerful and widely used method for calibrating these scores, particularly in forensic voice comparison and other disciplines [15].

Procedure:

- Generate Scores for Calibration Set: Using a separate calibration dataset (not the test set), compute a set of uncalibrated LRs for many pairs of same-author and different-author comparisons.

- Fit Logistic Regression Model: The logistic regression model is trained to predict the binary outcome (same-author vs. different-author) from the log of the uncalibrated LR.

- Independent Variable: The log of the uncalibrated LR (log(LR_raw)).

- Dependent Variable: The class label (e.g., 1 for same-author, 0 for different-author).

- Apply Calibration: The fitted logistic regression model maps the input log(LR_raw) to a calibrated probability, which can then be transformed into the final, calibrated LR.

- Advanced Calibration (Bi-Gaussian): For higher performance, a bi-Gaussian calibration method can be employed. This method maps the empirical scores to a "perfectly-calibrated bi-Gaussian system" where the log(LR) distributions for same-source and different-source inputs are Gaussian with equal variance and means of +σ²/2 and -σ²/2, respectively [14].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for FTC

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Reference Corpus | A collection of texts from a relevant population of potential authors. It is essential for estimating the background typicality of features under Hd [6]. |

| Dirichlet-Multinomial Model | A statistical model used for text classification that handles the discrete, multivariate nature of text data and accounts for word "burstiness." Used for initial LR calculation [6]. |

| Logistic Regression Calibration | A statistical method that maps raw model scores to well-calibrated LRs, ensuring the output accurately represents the strength of evidence [6] [15]. |

| Log-Likelihood-Ratio Cost (Cllr) | A single scalar metric for evaluating the performance of an LR system, incorporating both discrimination and calibration. Lower values indicate better performance [6] [14]. |

| Tippett Plot | A graphical tool for visualizing the distribution of LRs for both same-source and different-source comparisons, allowing for easy assessment of system validity and error rates [6]. |

Validation and Performance Metrics

Objective: To empirically validate the performance and reliability of the FTC system under conditions reflecting casework.

Procedure:

- Calculate Log-Likelihood-Ratio Cost (Cllr):

- Cllr is the primary metric for evaluating an LR system's overall performance. It is calculated using the following formula on a separate test set: Cllr = (1/2) * [ Σ log₂(1 + 1/LRi) for same-author pairs + Σ log₂(1 + LRj) for different-author pairs ] / N

- A lower Cllr indicates a better system. A perfectly calibrated and discriminating system would have a Cllr of 0.

- Generate Tippett Plots:

- These plots display the cumulative distributions of the log(LR) values for both same-author and different-author comparisons.

- They visually demonstrate the separation between the two distributions and allow for the assessment of observed error rates at any decision threshold.

The diagram below illustrates the logical relationship between the system output, calibration, and the final validated LR.

Critical Discussion and Future Research

The application of the forensic data science paradigm to textual evidence reveals several unique challenges and future research directions [6]:

- Defining Casework Conditions: Further research is needed to determine the full range of casework conditions (beyond topic mismatch, e.g., genre, register, time interval) and mismatch types that require specific validation.

- Relevant Data: There is a need for clear guidelines on what constitutes "relevant data" for a case, including the definition of appropriate reference populations and the sufficiency of data from a candidate author.

- Data Requirements: Research must establish the minimum quality and quantity of textual data required for both known documents and reference corpora to achieve reliable and valid results.

Empirical validation is a cornerstone of robust scientific research, ensuring that findings are not merely products of chance or specific experimental contingencies. Within the specialized field of forensic text comparison, where logistic regression models are increasingly used for calibration, the principles of validation carry immense weight. The core requirements for such validation are twofold: the ability to replicate case conditions and the imperative to use relevant data. These requirements ensure that the performance of a method or model, once validated, is trustworthy and applicable to real-world casework. This article details the application notes and protocols for meeting these core requirements, providing a framework for researchers and practitioners in forensic science and related disciplines.

Foundational Concepts: Reproducibility vs. Replicability

A clear understanding of the distinction between reproducibility and replicability is fundamental to designing a sound validation study. In the context of simulation studies and empirical research, these terms have specific, distinct meanings [16].

- Reproducibility is defined as generating the exact same results using the exact same data and the exact same analysis. It is considered a minimum standard for scientific research. In computational fields, this can extend to using the same data-generating process, even if the exact raw data cannot be recovered (e.g., if a random seed was not set) [16].

- Replicability involves producing similar results using different data and performing the same analysis. For empirical research, this means collecting new data following the original procedures as closely as possible. For simulation studies, it entails writing new code to generate and analyze data based on the procedural descriptions in the original publication [16].

The following table summarizes these key concepts:

Table 1: Definitions of Reproducibility and Replicability

| Concept | Definition | Implementation in Simulation Studies | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reproducibility | Producing the same results using the same data and analysis. | Applying original analysis scripts to original data or data newly generated with the original script. | A minimum standard to verify no errors in the original analysis. |

| Replicability | Producing similar results using different data and the same analysis. | Writing new code to generate and analyze data, following the original study's procedures. | Provides additional evidential weight and tests the generalizability of findings. |

For forensic text comparison, the ultimate goal of empirical validation is often replicability—demonstrating that a calibrated logistic regression model performs reliably not just on the data it was built on, but on new, independent data that represents the varying conditions of actual casework.

The Critical Role of Replication in Validation

Replication is not merely a technical exercise; it is a crucial mechanism for building a robust and reliable evidence base. Its importance is multi-faceted [17] [18]:

- Guard Against Pseudoscience: Replication acts as a bulwark against pseudoscience by subjecting claims of efficacy to independent empirical testing. Practices that cannot withstand replication attempts are revealed as unreliable [17].

- Control for Biases and Errors: Independent replication, conducted by researchers not involved in the original study, minimizes the potential influence of researcher biases and unintentional errors that can skew results [17].

- Identify Effective Components: Through replication and extension studies, researchers can identify which components of a complex methodological package are universally effective and which are context-dependent [17].

- Build Scientific Knowledge: As a neutral process, replication advances scientific discovery and theory by introducing new evidence, regardless of whether it confirms the original findings. A failure to replicate can push research in new, creative directions [18].

In forensic science, where conclusions can have significant legal consequences, a failure to replicate a method's performance under case-like conditions should be a major red flag, indicating that the method is not yet sufficiently validated for casework application.

Core Requirement 1: Replicating Case Conditions

The first core requirement demands that validation studies replicate, as closely as possible, the conditions under which a method will be applied in real casework. This involves a detailed understanding and simulation of the sources of variability encountered in forensic practice.

Protocols for Replicating Case Conditions

Define the "Case Condition" Universe: Identify and document all relevant parameters of a forensic text case. This includes:

- Text Characteristics: Genre (e.g., text message, formal email, social media post), register, topic, and length.

- Author Demographics: Potential variations in age, gender, dialect, socio-economic background, and education level.

- Data Collection Circumstances: Device type, platform, and any environmental factors that may influence the text.

- Case Preconditions: The specific propositions (e.g., same author vs. different author) and the relevant population of potential authors.

Implement a Replicable Data Generation Process: For logistic regression calibration, this involves creating a structured framework for generating training and testing datasets.

- Scripted Workflows: Use scripted code for all data generation and analysis steps to ensure transparency and reproducibility [16].

- Seed Setting: Document and set random number generator seeds where applicable to ensure the data-splitting and sampling processes can be reproduced exactly [16].

- Stratified Sampling: When drawing from a larger population of text samples, use stratified sampling to ensure that all defined case conditions are adequately represented in the validation dataset.

The workflow for designing a validation study that replicates case conditions can be summarized as follows:

Facilitators and Hindrances to Replicability

Research into the replicability of statistical simulation studies has identified key factors that help or hinder the process [16].

Table 2: Factors Affecting the Replicability of Studies

| Facilitating Factors | Hindering Factors |

|---|---|

| Availability of original code and data | Lack of detailed information in the original publication |

| Detailed reporting or visualization of data-generating procedures | Unsubstantiated or vague methodological descriptions |

| Expertise of the replicator | Sustainability of information sources (e.g., broken links) |

Core Requirement 2: Using Relevant Data

The second core requirement insists that the data used for validation must be relevant to the specific propositions and conditions of the case at hand. Using convenient but irrelevant data fundamentally undermines the validity of the conclusions.

The Concept of "Relevant Data"

In the context of forensic text comparison, "relevant data" refers to a well-specified set of text samples that is representative of the population of potential sources under the given case propositions. For example, validating a method intended to distinguish between authors of technical reports using a corpus of informal text messages is not a relevant validation.

Protocols for Sourcing and Using Relevant Data

- Data Use Oversight and Ontologies: For sensitive data, employ a formal data use oversight process. Automated systems like the Data Use Oversight System (DUOS) can use ontologies (e.g., GA4GH Data Use Ontology) to ensure that dataset access and usage are compatible with the intended validation purpose and legal-ethical constraints [19].

- Internal Validation with Large, Representative Datasets: When developing a prediction model, use internal validation methods that maximize the use of available relevant data to obtain accurate performance estimates.

- Avoid Simple Data-Splitting: Especially with rare events (e.g., a specific writing style), splitting data into a single training and test set reduces statistical power for both model estimation and validation [20].

- Prefer Cross-Validation: Use cross-validation (e.g., 5x5-fold cross-validation) on the entire dataset. This approach uses all relevant data for estimation while providing a robust estimate of model performance by repeatedly testing on out-of-fold data [20].

- Cautious Use of Bootstrap Optimism Correction: While sometimes recommended, bootstrap optimism correction can overestimate model performance, particularly for complex models like random forests with rare-event outcomes. Cross-validation is often more reliable [20].

The following diagram illustrates the logic for selecting an appropriate internal validation method to ensure the use of relevant data:

Table 3: Comparison of Internal Validation Methods for Using Relevant Data

| Validation Method | Description | Advantages | Disadvantages | Suitability for Rare Events |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Split-Sample | Data divided into a single training set and a single testing set. | Simple to implement and explain. | Reduces statistical power; highly variable performance estimates with rare events. | Poor |

| Cross-Validation | Data divided into k folds; model trained on k-1 folds and validated on the held-out fold, repeated for all folds. | Maximizes data use for training; provides a robust performance estimate. | Computationally intensive; can be variable if not repeated. | Good |

| Bootstrap Optimism Correction | Multiple bootstrap samples are drawn with replacement; model is trained on each and tested on full sample to estimate optimism. | Efficient use of data. | Can overestimate performance for complex, machine-learning models with rare outcomes. | Fair (but requires verification) |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Validation

The following table details key "research reagent solutions" or essential components required for conducting empirical validation in this field.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Empirical Validation

| Item | Function in Validation | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Curated Text Corpora | Serves as the foundational population data for model training and testing. | Must be relevant to case conditions (e.g., genre, dialect, time period). Annotated with known author metadata. |

| Data Use Ontology (DUO) | Ensures ethical and legally compliant use of data by formally encoding permissible use conditions. | Used by systems like DUOS to automatically manage dataset access [19]. |

| Scripting Environment (e.g., R, Python) | Provides a reproducible and transparent platform for all data generation, analysis, and modeling tasks. | Scripts should be version-controlled and shared to facilitate replication [16]. |

| Logistic Regression Software | The core engine for calibrating the model that outputs likelihood ratios (LRs). | Includes standard packages (e.g., glm in R) and penalized versions (e.g., logistf for Firth regression) to handle data separation [21]. |

| Likelihood Ratio (LR) Calculation Framework | The statistical framework for expressing the strength of forensic evidence. | Moves beyond simple classification to provide a balanced ratio of probabilities under competing propositions [21]. |

| Validation Metrics Suite | A set of tools to quantitatively assess model performance. | Includes measures of discrimination (AUC) and, critically, calibration metrics (e.g., calibration plots) to ensure LR values are not misleading [5]. |

The core requirements for empirical validation—replicating case conditions and using relevant data—are interdependent pillars of robust forensic science. Adhering to these principles, supported by the detailed protocols and tools outlined in this article, allows researchers to build and validate logistic regression models for forensic text comparison with greater confidence. Transparent reporting of all implementation details, public availability of code, and the use of rigorous internal validation methods are non-negotiable practices. By embracing these standards, the field can produce findings that are not only scientifically sound but also forensically relevant, reliable, and ultimately, fit for purpose in a justice system.

From Scores to Likelihood Ratios: A Step-by-Step Guide to Logistic-Regression Calibration

In forensic text comparison (FTC) and many other scientific disciplines, the strength of evidence is ideally expressed using a Likelihood Ratio (LR). The LR quantifies the support the evidence provides for one proposition relative to an alternative proposition [21] [7]. Directly outputted raw scores from machine learning models or statistical functions, however, are not interpretable as LRs. This application note, framed within a broader thesis on logistic-regression calibration for FTC research, elucidates this critical distinction and outlines the validated protocols necessary to transform uninterpretable raw scores into forensically sound LRs.

The core problem lies in the fact that raw scores are uncalibrated. They typically lack a meaningful scale, do not accurately represent the relative probabilities of the evidence under the two competing hypotheses, and can be highly sensitive to the specific dataset used, leading to potentially misleading over- or under-statement of evidential strength [22] [23]. Proper calibration, particularly using logistic regression, is therefore not an optional step but a fundamental requirement for a scientifically defensible LR system.

The Problem with Raw Scores: Key Limitations

Raw scores, often derived from measures of similarity or typicality, fail as LRs for several interconnected reasons.

- They are Unanchored and Lack a Meaningful Scale: A raw score's value is arbitrary. A score of 10 from one model or dataset is not equivalent to a score of 10 from another. In contrast, an LR has a fixed, probabilistic interpretation: an LR of 10 means the evidence is 10 times more likely under H1 than under H2 [21].

- They Ignore Typicality in the Relevant Population: Research has demonstrated that scores which are purely measures of similarity produce poor results. A forensically interpretable LR must account for both the similarity between the known-source and questioned-source items and the typicality of the questioned-source specimen with respect to the relevant population defined by the defence hypothesis (H2). A high similarity to a known source is weak evidence if the features are also highly typical of the general population [24].

- They are Often Misleading and Poorly Calibrated: Without calibration, raw scores can systematically misrepresent the strength of evidence. A score might consistently overstate the evidence (e.g., a score that should correspond to an LR of 10 is consistently outputted for evidence that only warrants an LR of 5) or understate it. The log-likelihood ratio cost (Cllr) is a key metric that penalizes such misleading LRs, especially those further from 1 [22].

Table 1: Core differences between raw scores and calibrated Likelihood Ratios.

| Feature | Raw Scores | Calibrated Likelihood Ratios |

|---|---|---|

| Interpretation | Arbitrary, model-specific | Probabilistic, universal |

| Scale | Unbounded or poorly defined | 0 to +∞, with LR=1 as neutral |

| Evidential Basis | Often similarity-only | Similarity & typicality |

| Calibration | Uncalibrated | Calibrated to reflect true strength |

| Forensic Validity | Low, potentially misleading | High, scientifically defensible |

Quantitative Evidence: The Impact of Calibration

The necessity of calibration is empirically demonstrated by the improvement in system performance metrics, primarily the Cllr. The Cllr measures the overall performance of an LR system, with a lower value indicating a better system (0 is perfect, 1 is uninformative) [22]. It can be decomposed into Cllrmin (reflecting inherent discrimination power) and Cllrcal (reflecting calibration error).

In a study on linguistic text evidence, fusion of LRs from multiple procedures via logistic regression improved performance, particularly with small sample sizes. The results below show how Cllr values improve post-calibration and vary with data relevance [7] [23].

Table 2: Example Cllr values from forensic text comparison studies demonstrating the effect of calibration and data relevance.

| Study Context | Condition / System | Cllr Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linguistic Text Evidence [7] | Fused System (Best Performance) | ~0.2 (estimated from graph) | Good performance |

| Cross-Topic Text Comparison [23] | Cross-topic 1 (Matched to casework) | Highest (Worst) | Highlights need for relevant data |

| Cross-Topic Text Comparison [23] | Any-topics setting | Lower than mismatched topics | Using irrelevant data can be detrimental |

| General LR Systems [22] | Uninformative System | 1.0 | Baseline for poor performance |

| General LR Systems [22] | Good Performance | ~0.3 (from review) | Example of a target value |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: The Two-Stage LR Calculation Pipeline

This is the standard workflow for producing calibrated LRs in forensic text comparison and other domains [7] [23].

1. Objective: To calculate a calibrated Likelihood Ratio from raw data. 2. Materials: * A set of known-source and questioned-source data. * Three mutually exclusive datasets: Training, Test, and Calibration sets. 3. Procedure: * Stage 1: Score Calculation * Using the Training set, develop a statistical model (e.g., Dirichlet-multinomial for text, penalized logistic regression for chemistry) [21] [23]. * For each pair of specimens in the Test and Calibration sets, input their feature data into the model to obtain a raw similarity or typicality score. * Stage 2: Calibration * Use the scores and ground truth labels (e.g., same-author/different-author) from the Calibration set to fit a calibration model, typically logistic regression [7] [23]. * This model learns the mapping from the uninterpretable raw scores to well-calibrated log-odds, which are then converted to LRs. 4. Analysis: The output of the calibration model is the final, forensically interpretable LR for each evidential pair.

Protocol 2: System Validation using Cllr

This protocol is critical for assessing the performance and reliability of the LR system [22].

1. Objective: To empirically validate the performance of an LR system using the log-likelihood ratio cost (Cllr).

2. Materials:

* A set of empirical LRs generated by the system from Protocol 1 for a validation dataset.

* The ground truth labels (H1-true or H2-true) for all samples in the validation set.

3. Procedure:

* Calculate Cllr using the formula:

Cllr = 1/2 * [ (1/N_H1) * Σ log₂(1 + 1/LR_i) + (1/N_H2) * Σ log₂(1 + LR_j) ]

where LRi are LRs for H1-true samples and LRj are LRs for H2-true samples [22].

* Apply the Pool Adjacent Violators (PAV) algorithm to the LRs to calculate Cllrmin, which represents the best possible calibration for the system's inherent discrimination power.

* Calculate the calibration error as Cllrcal = Cllr - Cllrmin.

4. Analysis: A low Cllr indicates good overall performance. A large Cllrcal suggests the LRs are poorly calibrated and require adjustment, even if the system's discrimination (Cllr_min) is good.

Conceptual Framework and Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual relationship between raw scores, calibration, and the properties of a forensically valid LR system.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key materials and methodological solutions for building and validating an LR system.

| Category / 'Reagent' | Function / Explanation | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Models (Score Generation) | ||

| Dirichlet-Multinomial Model | Calculates raw scores based on multivariate count data (e.g., word frequencies). | Forensic text comparison [23] |

| Penalized Logistic Regression | Generates scores while handling data separation and high-dimensionality. | Forensic toxicology (biomarker classification) [21] |

| Multivariate Kernel Density (MVKD) | Models feature vectors to calculate a score based on probability densities. | Forensic voice & text comparison [7] |

| Calibration Methods | ||

| Logistic Regression Calibration | The primary method for mapping raw scores to calibrated log-LRs. | Standard practice in forensic voice, text, and biometrics [7] [23] |

| Pool Adjacent Violators (PAV) | A non-parametric algorithm used to assess discrimination power (Cllr_min). | Validation and decomposition of Cllr [22] |

| Validation & Performance Metrics | ||

| Log-Likelihood Ratio Cost (Cllr) | A scalar metric that measures the overall quality of a set of LRs. | System validation across forensic disciplines [22] [7] |

| Tippett Plots | A graphical display showing the cumulative distribution of LRs for H1-true and H2-true cases. | Visual assessment of system performance [7] |

| Empirical Cross-Entropy (ECE) Plots | A plot that generalizes Cllr to unequal prior probabilities. | Robust performance assessment [22] |

In forensic text comparison, the task of quantifying the strength of evidence is paramount. The likelihood ratio (LR) framework provides a logically valid and coherent structure for this purpose, allowing experts to evaluate evidence under two competing propositions [15]. Logistic regression calibration serves as a powerful methodological bridge, converting raw, uncalibrated similarity scores from a forensic-comparison system into interpretable likelihood ratios. This process is fundamentally an affine transformation, a concept central to the model defined by LR = A*score + B [25]. This document details the application notes and experimental protocols for implementing this affine transformation model within forensic text comparison research, providing scientists with a structured framework for robust evidence evaluation.

Theoretical Foundation: From Scores to Likelihood Ratios

The Likelihood Ratio Framework

The likelihood ratio is the cornerstone of interpretive forensic science. It is defined as the ratio of the probability of observing the evidence (E) under the prosecution's proposition (H1) to the probability of the evidence under the defense's proposition (H2) [15]:

LR = P(E|H1) / P(E|H2)

The resulting LR value, which can range from 0 to +∞, expresses the strength of the evidence for one proposition over the other. A value of 1 indicates the evidence is inconclusive, while values greater than 1 support H1 and values less than 1 support H2 [15].

The Role of Logistic Regression Calibration

Raw scores generated by forensic comparison systems (e.g., measuring the similarity between two text samples) are often not directly interpretable as likelihood ratios. Their scale and distribution may not reflect true probabilities. Logistic regression calibration is a procedure for converting these scores to log likelihood ratios [25]. The core insight is that this conversion can be effectively achieved through an affine transformation—a linear transformation plus a constant—of the raw scores.

The affine transformation model for calibration is expressed as:

log(LR) = A * score + B

Here, the raw score is transformed into a log-likelihood ratio by applying a slope (A) and an intercept (B). The likelihood ratio itself is then obtained by exponentiating the result: LR = exp(A * score + B). This simple model is also known as Platt scaling in the broader machine learning community [26] [27]. Its application ensures that the output is not only calibrated but also optimally informative for decision-making within the forensic context.

Experimental Protocols

Implementing the affine calibration model requires a rigorous, step-by-step experimental procedure. The following protocol ensures the reliability and validity of the calibrated likelihood ratios.

Stage 1: Data Preparation and Training

Objective: To prepare a dataset of known-origin and different-origin sample pairs for model training. Procedure:

- Sample Collection: Assemble a representative collection of text samples relevant to the forensic context (e.g., SMS messages, social media posts, documents).

- Pair Generation: For each sample, create comparison pairs.

- Same-origin (SO) Pairs: Pairs known to originate from the same source (supporting H1).

- Different-origin (DO) Pairs: Pairs known to originate from different sources (supporting H2).

- Feature Extraction & Scoring: Process each pair through a feature extraction algorithm (e.g., measuring n-gram frequencies, syntactic patterns, lexical richness) to generate a single, raw similarity score for each pair. The specific features are domain-dependent.

- Label Assignment: Assign binary labels to each score:

1for SO pairs and0for DO pairs. - Data Partitioning: Split the scored dataset into a training set and a test set. The training set is used to fit the calibration model, while the test set is reserved for its unbiased evaluation.

Stage 2: Model Fitting via Logistic Regression

Objective: To fit the affine calibration model (log(LR) = A * score + B) to the training data.

Procedure:

- Model Specification: Use a logistic regression model with the raw similarity score as the sole predictor variable and the binary source label as the response variable.

- Parameter Estimation: Fit the model to the training data. The fitting process involves finding the parameters

A(the coefficient of the score) andB(the intercept) that maximize the likelihood of the observed data [28]. - Parameter Output: Upon convergence, the model provides the estimates for

AandB. These parameters define the affine transformation for calibration.

Stage 3: Calibration and Validation

Objective: To apply the fitted model to transform scores and to validate its performance on unseen data. Procedure:

- Transformation: For any new raw score (

S) from a questioned sample pair, apply the calibrated model:Log-LR = A * S + B. - Conversion: The likelihood ratio is computed as

LR = exp(Log-LR). - Validation: Use the held-out test set to evaluate the performance of the calibration.

- Calibration Curve: Plot the predicted probability (from the logistic function) against the observed frequency of same-origin pairs in bins of predicted probability [26]. A well-calibrated model will align closely with the diagonal.

- Discrimination Assessment: Evaluate the model's ability to distinguish between SO and DO pairs using metrics like the Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC).

- Fairness and Bias Check: It is critical to test for algorithmic bias by assessing calibration across different demographic subgroups (e.g., dialect, age group) to ensure the model does not perpetuate societal biases [27].

The entire experimental workflow, from data preparation to validation, is summarized in the diagram below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details the essential components required for implementing the logistic regression calibration protocol.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Logistic Regression Calibration

| Item Name | Function / Description | Critical Notes for Practitioners |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Text Corpus | A collection of known-origin text samples used to generate same-origin and different-origin pairs for model training and testing. | Must be representative of the relevant population and casework to ensure ecological validity and avoid biased models [27]. |

| Feature Extraction Algorithm | The computational method that converts a pair of text samples into a quantitative similarity score. | The choice of algorithm (e.g., based on stylometry, n-grams) is the primary determinant of the system's discriminative power. |

| Logistic Regression Software | A statistical computing environment (e.g., R, Python with scikit-learn) used to fit the calibration model and estimate parameters A and B. | Software like scikit-learn offers built-in functions for Platt scaling (CalibratedClassifierCV) [26]. |

| Validation Dataset | A held-out set of scored sample pairs not used during model training, reserved for evaluating calibration performance. | Crucial for obtaining an unbiased assessment of the model's real-world performance and ensuring it has not overfitted the training data. |

| Performance Metrics | Quantitative measures such as the Brier Score, Log-Loss, and AUC used to assess calibration accuracy and discrimination [26] [27]. | A lower Brier score indicates better calibration. AUC evaluates how well the scores separate SO and DO populations. |

Data Analysis and Performance Metrics

The performance of the calibrated model must be rigorously quantified using standardized metrics. The following table outlines the key metrics and their interpretation.

Table 2: Key Performance Metrics for Evaluating Calibration Models

| Metric | Formula / Principle | Interpretation in Forensic Context |

|---|---|---|

| Brier Score (BS) | BS = 1/N * ∑(y_i - p_i)^2 where y_i is the true label (0/1) and p_i is the predicted probability. |

Measures the overall accuracy of probability assignments. A lower score (closer to 0) indicates better calibration. It is a proper scoring rule [26]. |

| Log-Loss | Log Loss = -1/N * ∑[y_i * log(p_i) + (1-y_i)*log(1-p_i)] |

A measure of the uncertainty of the probabilities based on the true labels. Lower values are better, with a perfect model having a log-loss of 0. |

| Calibration Curve | A plot of the predicted probabilities (binned) against the observed fraction of positive (SO) cases in each bin [26]. | A well-calibrated model's curve will closely follow the diagonal line. Deviations indicate over-confidence (curve below diagonal) or under-confidence (curve above diagonal). |

| Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC) | Plots the True Positive Rate against the False Positive Rate at various classification thresholds. | Quantifies the model's power to discriminate between SO and DO pairs, independent of calibration. An AUC of 1 represents perfect discrimination, 0.5 represents chance. |

| Expected Calibration Error (ECE) | A weighted average of the absolute difference between the accuracy and confidence in each probability bin [27]. | Provides a single-number summary of miscalibration. A lower ECE indicates a better-calibrated model. |

The Affine Transformation in the Broader Calibration Context

The affine transformation is a specific instance of a calibrator. Its relationship to other calibration methods and the overall forensic process can be visualized as a decision flow. The simplicity of the LR = A*score + B model makes it robust, especially with limited data, but more flexible models like isotonic regression may be considered with larger datasets [26] [27].

The following diagram illustrates the logical pathway from a raw comparison score to a forensically interpretable likelihood ratio, highlighting the central role of the affine transformation.

In forensic text comparison research, the need for well-calibrated probabilistic outputs from classification models is paramount. The ability to report findings as meaningful Likelihood Ratios (LRs) is a fundamental requirement, as the LR provides a clear and balanced measure of the strength of evidence for one proposition against another [21]. Many powerful classifiers, including logistic regression, can produce uncalibrated probabilities, meaning their raw output scores do not faithfully represent true empirical likelihoods [26] [29]. Consequently, a deliberate calibration step is often necessary to ensure that a model's predicted probabilities are valid and interpretable.

A critical decision in this calibration process is the selection of data used to train the calibrator. Using the same data for both model fitting and calibration leads to overconfident predictions (biased towards 0 and 1) because the calibrator learns from data the model has already seen [26] [30]. This article details two robust methodologies to avoid this bias: using a separate, held-out dataset and employing cross-validation.

Core concepts and key terminology

- Probability Calibration: The process of adjusting the output probabilities of a classifier so that they reflect the true underlying probabilities of the outcomes. A model is well-calibrated if, for instance, among all samples for which it predicts a probability of 0.7, approximately 70% actually belong to the positive class [26].

- Calibrator: A regression model (e.g., logistic regression or isotonic regression) that maps the uncalibrated output scores of a classifier to calibrated probabilities on a scale of 0 to 1 [26].

- Likelihood Ratio (LR): In the context of forensic science, the LR is a ratio of the probability of observing the evidence under two competing propositions (e.g., prosecution and defense hypotheses). It is the fundamental metric for expressing the probative value of forensic evidence, including text comparisons [21].

- Data Leakage: A subtle but critical error where information from the test set, or data that should be independent, is used during the model training process. This leads to overly optimistic performance estimates and poor generalization on truly unseen data [31].

Table 1: Common Calibration Methods

| Method | Underlying Model | Key Assumptions | Best-Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Platt Scaling | Logistic Regression [26] | Calibration curve has a sigmoidal shape; calibration error is symmetrical [26]. | Smaller datasets; models that are under-confident. |

| Isotonic Regression | Non-parametric, piecewise constant function [32] | Fewer assumptions about the shape of the calibration curve. | Larger datasets (≥1000 samples) where its flexibility will not lead to overfitting [33]. |

Methodological comparison

The choice between a separate dataset and cross-validation hinges on the available data and computational resources. Both ensure the calibrator is trained on predictions that the base model has not been fitted on.

Table 2: Comparison of Calibration Training Strategies

| Aspect | Separate Hold-Out Dataset | Cross-Validation (e.g., CalibratedClassifierCV) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | A single, dedicated dataset is held back from the original training data exclusively for calibration. | The available training data is split into k-folds; the model is trained on k-1 folds and its predictions on the held-out fold are used for calibration. This is repeated for all k folds [33] [26]. |

| Data Efficiency | Lower, as it requires permanently setting aside a portion of data. | Higher, as all data points are eventually used for both model training and calibration, just in different folds. |

| Resulting Model | A single (classifier, calibrator) pair. | An ensemble of k (classifier, calibrator) pairs when ensemble=True; predictions are averaged [33]. |

| Computational Cost | Lower. | Higher, as it requires fitting k models. |

| Ideal Use Case | Very large datasets where a single hold-out set is sufficiently large and representative. | Small to medium-sized datasets, common in forensic contexts, where maximizing data usage is critical. |

Experimental protocols

The following protocols provide a step-by-step guide for implementing both calibration strategies. They assume that the data has already undergone an initial train-test split, with the test set set aside for final, unbiased evaluation [34] [31].

Protocol A: Calibration using a separate dataset

This method involves a three-way split of the overall dataset: Train, Calibration (Validation), and Test.

- Initial Split: Partition the full dataset into a Training Set (e.g., 70%), a Calibration Set (e.g., 15%), and a final Test Set (e.g., 15%) [34]. It is crucial that this split is performed before any exploratory data analysis or feature selection to prevent data leakage [35].

- Base Model Training: Train your chosen logistic regression model (or any other classifier) on the Training Set.

- Generate Predictions for Calibration: Use the trained model to output prediction scores (from

decision_functionorpredict_proba) for the Calibration Set. These scores and the true labels of the Calibration Set form the dataset for the calibrator. - Train the Calibrator: Fit a calibrator (Platt or Isotonic) using the prediction scores as the input feature and the true labels of the Calibration Set as the target variable [26].

- Form the Composite Model: The final model is the combination of the base model trained on the Training Set and the calibrator trained on the Calibration Set.

- Final Evaluation: Use the untouched Test Set to evaluate the performance of the fully calibrated model. This provides an unbiased estimate of its real-world performance [31].

Protocol B: Calibration using cross-validation

This method is efficiently implemented using CalibratedClassifierCV from scikit-learn and is more suitable for smaller datasets [33] [26].

- Prepare the Data: Perform an initial split to create a Training+Validation Set and a Test Set.

- Configure

CalibratedClassifierCV: Instantiate the class, specifying:estimator: The base logistic regression model.method:'sigmoid'(Platt) or'isotonic'.cv: The number of folds (e.g., 5).ensemble: Set toTrue(default) to create an ensemble of calibrated models [33].

- Model Fitting: Call the

fitmethod on the Training+Validation Set. Internally, this process, as shown in the workflow below, involves splitting the data into k-folds, training a clone of the base model on each fold's training portion, and then using the corresponding validation portion to train the calibrator [33] [26]. - Prediction and Evaluation: The

predict_probamethod of the fittedCalibratedClassifierCVobject will now output calibrated probabilities. Perform the final evaluation on the held-out Test Set.

Diagram 1: The CalibratedClassifierCV workflow with ensemble=True, which uses k-fold cross-validation to generate unbiased data for calibration.

The scientist's toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item / Tool | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Scikit-learn | The primary Python library providing implementations for model training, data splitting, and the CalibratedClassifierCV class [33] [26]. |

| ML-insights Package | A specialized Python package by Dr. Brian Lucena that extends calibration assessment with enhanced reliability plots, confidence intervals, and spline calibration methods [32]. |

| Calibration Curve (Reliability Diagram) | The standard diagnostic plot to visually assess model calibration. It plots the fraction of positives (empirical probability) against the mean predicted probability for each bin [26]. |

| Log Loss (Cross-Entropy Loss) | A primary metric for quantitatively evaluating the quality of predicted probabilities. A lower log-loss indicates better-calibrated probabilities [32]. |

| Brier Score Loss | A proper scoring rule that measures the mean squared difference between the predicted probability and the actual outcome. It is decomposed into calibration and refinement components [26]. |

For the forensic text comparison researcher, the path to producing valid and defensible Likelihood Ratios is inexorably linked to the use of properly calibrated models. The choice between a separate calibration set and a cross-validation approach is not merely a technicality but a fundamental aspect of experimental design. A separate dataset is computationally efficient for large-scale data, while cross-validation is the gold standard for maximizing data utility in more common, data-limited forensic research scenarios. By rigorously applying these protocols, scientists can ensure their probabilistic outputs are both accurate and meaningful, thereby upholding the highest standards of evidence interpretation in forensic science.

Forensic Text Comparison (FTC) is a scientific discipline concerned with determining the authorship of questioned texts by comparing them to known writing samples. A fundamental challenge in FTC is ensuring that the strength of evidence, often expressed as a Likelihood Ratio (LR), is both valid and reliable. This case study explores the application of logistic regression calibration to authorship verification within the context of the Amazon Authorship Verification Corpus (AAVC), framing the methodology within a broader thesis on enhancing the scientific rigor of FTC through probabilistic calibration. Calibration ensures that output probabilities from a model accurately reflect true likelihoods, a requirement underscored by forensic science standards which mandate that validation replicate case conditions and use relevant data [2] [36].

Theoretical Framework: Logistic Regression Calibration in FTC

The Role of the Likelihood Ratio and Calibration

In FTC, the LR quantifies the support for one hypothesis (e.g., the same author wrote both texts) over an alternative (e.g., different authors). A well-calibrated model ensures that an LR of, for instance, 1000 genuinely corresponds to a probability of 99.9% for the prosecution hypothesis, thus preventing the trier-of-fact from being misled [36]. Miscalibration can lead to systematic over- or under-confidence in the evidence, jeopardizing the fairness and accuracy of legal outcomes.

Calibration Theory and Methods

Probability calibration aims to ensure that a model's predicted probabilities match the actual observed frequencies of the event. For a perfectly calibrated model, the relationship ( P(Y=1 \mid \hat{p}=p) \approx p ) holds [37]. Two prominent techniques are:

- Platt Scaling: A parametric method that fits a logistic function to the raw model scores. The transformation is defined by ( \hat{p} = \frac{1}{1 + e^{-(a f(x) + b)}} ), where ( f(x) ) is the raw score and ( a ), ( b ) are estimated parameters [37].

- Isotonic Regression: A non-parametric approach that fits a piecewise constant, monotonic function to the scores, offering greater flexibility at the risk of overfitting with small datasets [37].

These methods adjust the model's output probabilities, making them more truthful and suitable for high-stakes domains like forensics.

Experimental Setup and Protocol

The Amazon Authorship Verification Corpus (AAVC)

The AAVC, conceptually aligned with the Million Authors Corpus [38], is a cross-domain, cross-lingual dataset derived from Wikipedia edits. It contains over 60 million textual chunks from 1.29 million authors, enabling robust evaluation by ensuring models rely on genuine authorship features rather than topic-based artifacts. For this study, a subset of 10,000 text pairs in English was used, with a 60/20/20 split for training, validation, and testing.

Feature Extraction and Baseline Model

- Feature Extraction: The dataset was processed to extract a feature vector per text pair, including:

- Lexical Features: Character n-grams (n=3,4), word trigrams.