Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS): A Comprehensive Review of Principles, Biomedical Applications, and Analytical Advancements

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS), an emerging atomic emission technique renowned for its rapid, multi-elemental analysis capabilities with minimal sample preparation.

Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS): A Comprehensive Review of Principles, Biomedical Applications, and Analytical Advancements

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS), an emerging atomic emission technique renowned for its rapid, multi-elemental analysis capabilities with minimal sample preparation. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the fundamental principles of LIBS and its operational mechanics. The review systematically covers its diverse methodological applications—from pharmaceutical tablet analysis and quality control to biomedical diagnostics and elemental mapping in tissues. It further addresses key analytical challenges, including signal optimization and matrix effects, while evaluating the technique's performance against established methods like ICP-MS. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with cutting-edge applications and validation studies, this work serves as a critical resource for understanding LIBS's potential as a transformative tool in both industrial and clinical settings.

The Fundamentals of LIBS: From Laser-Plasma Interaction to Spectral Fingerprinting

Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS) is a rapid, versatile analytical technique used for the elemental analysis of materials. Its core principle involves using a laser pulse to generate a microplasma on a sample surface. As this plasma cools, it emits atomic and ionic radiation that is characteristic of the elements present, serving as a unique "fingerprint" for their identification and quantification [1]. This technique is valued for its minimal sample preparation, capability for in-situ analysis, and applicability across diverse fields such as biomedical research, environmental monitoring, industrial applications, and geological mining [1].

Core Physical Principles

Laser Ablation and Plasma Formation

The LIBS process is initiated when a high-powered, focused laser pulse is directed at the sample surface. This interaction ablates a minute volume of material (nanograms to picograms), creating a vapor plume. The leading part of the laser pulse further interacts with this vapor, exciting and ionizing its constituents to form a high-temperature plasma plume (often at temperatures of 10,000–20,000 K) [1]. The fundamentals of this laser-matter interaction, various forms of ablated material, and subsequent plasma interaction are governed by complex phenomena including laser parameters (wavelength, pulse duration, energy) and specimen properties [1].

Plasma Expansion and Cooling

Following the laser pulse, the plasma expands rapidly and begins to cool. The lifetime and evolution of this plasma depend significantly on the laser pulse duration. For nanosecond (ns) laser pulses, plasma formation occurs during the pulse, with the trailing part of the pulse reheating the plasma and leading to a longer lifetime (on the order of microseconds, µs). In contrast, for femtosecond (fs) laser pulses, plasma is formed after the laser pulse, evolves faster, and has a shorter lifetime (several hundred nanoseconds) [1]. The absence of laser-plasma interaction in fs-LIBS reduces the heat-affected zone, offering higher ablation efficiency and less dependence on the material matrix [1].

Atomic and Ionic Emission

As the plasma cools, the excited atoms and ions within the plasma decay to lower energy states, emitting photons at specific wavelengths. The emitted light is collected by a spectrometer, which separates it into its constituent wavelengths to produce a spectrum. Each element in the periodic table possesses a unique set of emission lines, determined by its electronic energy level structure. The analysis of these spectral lines, including their presence (for qualitative analysis) and intensity (for quantitative analysis), reveals the elemental composition of the sample [1]. The underlying mechanisms for understanding LIBS analytical outcomes are governed by theoretical models, with local thermodynamic equilibrium (LTE) being the most commonly used for plasma modeling [1].

Experimental Protocols

LIBS Setup and Workflow

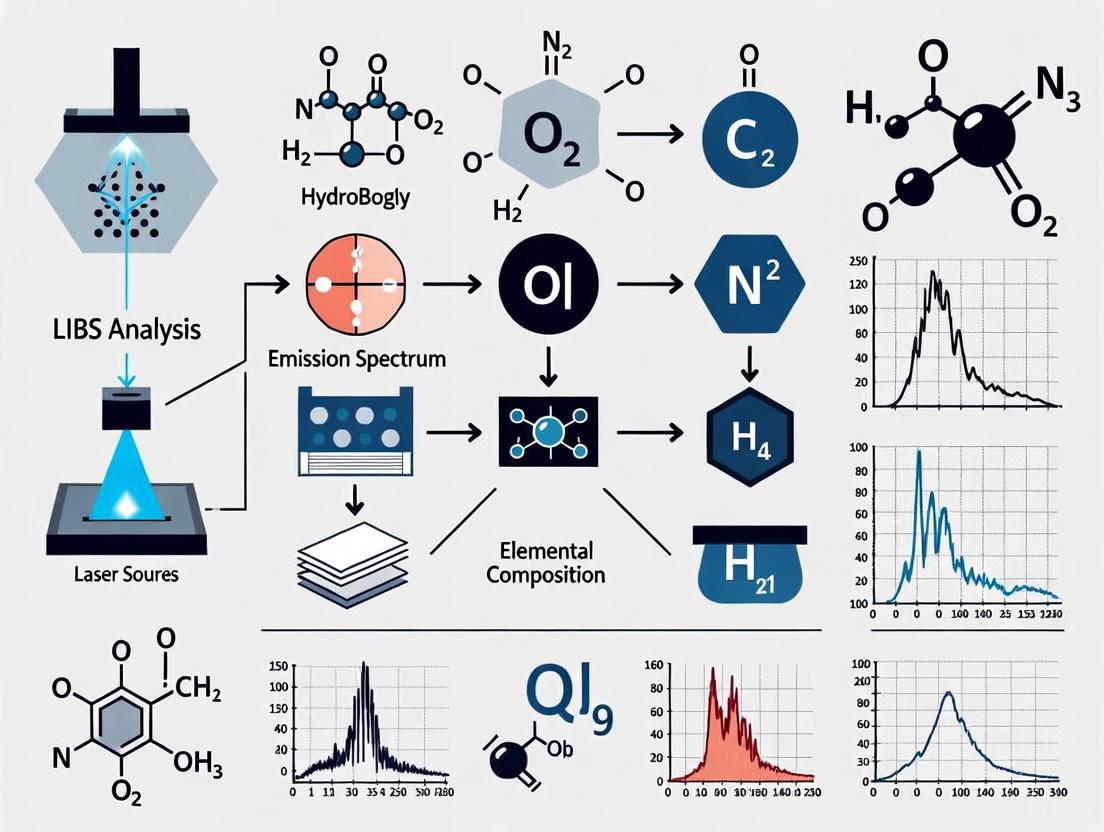

A standard LIBS apparatus consists of several key components: a pulsed laser source (commonly Nd:YAG), optics for focusing the laser beam, a sample stage, a system for collecting the plasma light (lens and optical fiber), a spectrometer, and a detector (such as an ICCD or CCD camera) [1]. The general workflow for a LIBS experiment is illustrated below.

Protocol for Custom Color Sample Analysis (Psychophysical Context)

This protocol is adapted for studies requiring highly controlled, closely related color pairs for visual discrimination experiments, such as those investigating low vision [2].

- Objective: To produce and analyze pairs of color patches with minimal, perceptually equidistant color differences using a calibrated inkjet printer and stabilized LED lighting.

Materials & Equipment:

- High-quality inkjet printer (e.g., Canon image PROGRAF PRO-300).

- Matte photo paper.

- Spectrophotometer for color measurement.

- Custom LED lighting system with spectral power distribution (SPD) stabilization.

- Software for color management and data analysis.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Color Space Sampling: Generate a set of reference color patches by sampling the CIELAB color space using a non-Euclidean color difference formula (CIEDE2000 or ΔE00). Utilize a pre-calculated, tabulated sampling grid (

CIELABTab00) where each color is equidistant (e.g., ΔE00 = 0.5) from its six neighbors [2]. - Printer Characterization and Calibration: Bypass the operating system's default color management. Use a color management process based on polyharmonic spline and tetrahedral interpolation to create a precise profile linking the printer's native RGB values to the target CIELAB coordinates. This ensures accurate color reproduction [2].

- Sample Printing: Print the generated color patches. For a discrimination experiment, select pairs of colors that are colorimetrically close and equidistant according to the ΔE00 metric [2].

- Lighting Stabilization: Implement a closed-loop feedback system to stabilize the Spectral Power Distributions (SPDs) of the LED lighting unit. This is critical to eliminate fluctuations caused by heat buildup or aging components, which could otherwise introduce unwanted variables in color perception [2].

- Data Collection and Analysis: Present the printed color pairs to study participants under the stabilized light. Use a paired comparison method to gather data on color discrimination thresholds. Analyze the results to determine the just-noticeable differences (JND) under the optimized lighting conditions [2].

- Color Space Sampling: Generate a set of reference color patches by sampling the CIELAB color space using a non-Euclidean color difference formula (CIEDE2000 or ΔE00). Utilize a pre-calculated, tabulated sampling grid (

Protocol for Cement Content Analysis in Concrete

This protocol demonstrates a specific materials science application of LIBS for non-destructive, in-situ analysis [3].

- Objective: To quantitatively estimate the cement content in concrete samples using spatially resolved LIBS.

Materials & Equipment:

- Pulsed laser source (e.g., Nd:YAG).

- Spectrometer with high resolution.

- Motorized sample stage for raster scanning.

- Concrete samples (prepared models and real-world samples).

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Sample Preparation and Modeling: Begin by creating mesoscale concrete models with known cement content. These models help identify key experimental parameters such as optimal spatial resolution, measurement area, and boundary effects [3].

- LIBS Raster Scanning: Focus the laser pulse on the concrete sample surface. Raster-scan the laser across a defined area to build a spatially resolved chemical map of the surface. The plasma emission at each point provides the local elemental composition, allowing differentiation between cement paste, aggregates, and voids [3].

- Spectral Clustering and Data Processing: Process the collected spectra using multivariate analysis. Combine Principal Component Analysis (PCA) with density-based spectral clustering to achieve clear separation between the different phases of the concrete (cement paste vs. aggregate) [3].

- Quantification: Correlate the classified spectral data with the known composition of the models to estimate the cement content in unknown samples. Under optimized conditions, this method has demonstrated an average relative error of approximately 8%, an improvement over traditional destructive methods [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 1: Key reagents, materials, and equipment for LIBS experiments.

| Item | Function/Description | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Pulsed Laser | Generates high-energy pulses for sample ablation and plasma initiation. Common types include Nd:YAG (Nanosecond) and Femtosecond lasers. | Core component in all LIBS setups [1]. |

| Spectrometer | Disperses the collected plasma light into its constituent wavelengths to form a spectrum. | Elemental identification and quantification [1]. |

| Calibrated Printer & Matte Paper | Produces custom, colorimetrically accurate sample patches for psychophysical experiments. | Generating color pairs for vision studies [2]. |

| Stabilized LED Light Source | Provides consistent, flicker-free illumination with controlled Spectral Power Distribution (SPD). | Essential for visual experiments where lighting variability must be minimized [2]. |

| Reference Materials | Samples with known elemental composition (e.g., standard reference materials for CC-LIBS). | Used for calibration and validation of quantitative results [1]. |

| Mesoscale Concrete Models | Laboratory-made concrete samples with precisely defined composition. | Method development and parameter optimization for cement analysis [3]. |

Data Analysis and Quantification Methods

Data Processing Workflow

The journey from raw plasma emission to quantitative results involves several critical steps, increasingly supported by artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) models to handle spectral complexity and improve classification accuracy [1]. The following diagram outlines this workflow.

Quantitative Formalism in LIBS

Two primary formalisms are used for elemental quantification, each with distinct advantages and requirements.

Table 2: Comparison of quantitative methods in LIBS.

| Method | Principle | Requirements | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calibration-Curve LIBS (CC-LIBS) | Plots a calibration curve of emission line intensity versus concentration using standard reference materials. | Matrix-matched standard reference materials. | High accuracy when standards are well-matched. | Requires a set of reliable standards; prone to matrix effects [1]. |

| Calibration-Free LIBS (CF-LIBS) | Determines elemental concentration from the plasma emission spectrum based on theoretical models of plasma physics (LTE assumption), without standard references. | No standard references needed; requires accurate plasma temperature measurement. | Eliminates need for calibration standards; useful for unknown samples. | Relies on the validity of the LTE assumption; computationally intensive [1]. |

Advanced Applications in Biomedical and Materials Science

The application of LIBS continues to expand into diverse and complex fields. In oncology, LIBS has been effectively used to differentiate between malignant and normal tissues and to classify cancer stages and types based on the detection of elemental imbalances and biomarkers [1]. For instance, fs-LIBS has enabled high-resolution elemental imaging of melanoma tumour tissue with a spatial resolution of 15 µm [1]. In the analysis of calcified tissues (e.g., teeth, bones), LIBS serves as a powerful tool for inspecting minerals, mapping metabolic markers, and studying disorders that alter the crystallography of hydroxyapatite [1]. In materials science, as demonstrated in the cement analysis protocol, LIBS provides a rapid, non-destructive alternative to traditional methods, enabling quality control and diagnostics in construction and industrial manufacturing [3].

Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS) is a rapid, versatile form of atomic emission spectroscopy used for elemental analysis. The fundamental principle involves using a highly energetic, focused laser pulse to ablate a micro-volume of material, creating a transient plasma. As this plasma cools, the excited atoms and ions within it emit characteristic wavelengths of light; collecting and analyzing this emitted light with a spectrometer and detector allows for the determination of the sample's elemental composition [4] [1]. LIBS stands out for its minimal-to-no sample preparation requirements, capability for simultaneous multi-element detection, and potential for portability and in-situ analysis, making it applicable across fields from industrial sorting to medical diagnostics [1].

The core components of any LIBS system work in a tightly synchronized sequence. The laser serves as the excitation source, generating the optical energy required for plasma formation. The spectrometer acts as the separation tool, dispersing the collected plasma light into its constituent wavelengths. Finally, the detector functions as the measurement device, converting the dispersed optical signals into quantifiable electrical data for analysis. The performance and selection of these three components directly dictate the system's analytical capabilities, including its spectral resolution, limit of detection, and overall sensitivity.

Core Component Analysis

The analytical performance of a LIBS system is fundamentally governed by the technical specifications and synergistic operation of its three key components. The following sections provide a detailed breakdown of each component, with quantitative data summarized for easy comparison.

Lasers

The laser is the primary excitation source in a LIBS system, and its parameters critically influence plasma formation and the resulting spectral emission.

Key Laser Parameters and Typical Specifications

| Laser Parameter | Common Types / Values | Impact on LIBS Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Pulse Duration | Nanosecond (ns), Femtosecond (fs) [1] | ns-pulses: Longer plasma lifetime (µs), plasma-laser interaction, more thermal effects [1].fs-pulses: Shorter plasma lifetime (hundreds of ns), minimal thermal damage, reduced matrix effects, higher spatial resolution [1]. |

| Wavelength | UV to IR (e.g., 1064 nm Nd:YAG) [5] | Shorter wavelengths often lead to better ablation efficiency and plasma coupling with solid surfaces. |

| Pulse Energy | Millijoule (mJ) to Joule (J) range | Higher energy typically increases plasma volume and signal intensity, but can lead to excessive sample damage. |

| Repetition Rate | Single pulse to kHz [1] | Higher rates enable faster analysis and signal averaging for improved precision. |

Nanosecond (ns) Q-switched Nd:YAG lasers are the most commonly used lasers in LIBS due to their maturity and reliability. As utilized in a typical experimental setup for studying aluminum plasma, a Nd:YAG laser operating at its fundamental wavelength of 1064 nm, with a pulse duration of 7 ns and pulse energy of 94 mJ, can produce a laser fluence of approximately 24 J/cm² when focused onto a target [5]. In such ns-laser ablation, the plasma is formed during the laser pulse, and the trailing part of the pulse interacts with and reheats the plasma, leading to a longer plasma lifetime on the order of microseconds [1].

Femtosecond (fs) lasers represent an advanced development, offering significant advantages. Fs laser ablation depth of 6 µm on a thin tissue section of liver metastases from a colorectal cancer patient has been reported, allowing for fast in-depth multi-elemental profiling at cellular spatial resolution [1]. The ultra-short pulse duration means plasma forms after the laser pulse, virtually eliminating plasma-laser interaction. This results in a plasma lifetime of several hundred nanoseconds, significantly reduced thermal effects on the sample, and less dependence on the material's matrix, which is particularly beneficial for analyzing heterogeneous biological tissues [1].

Spectrometers

The spectrometer resolves the broad-spectrum light emitted by the plasma into its constituent wavelengths, creating the unique elemental fingerprint for analysis.

Spectrometer Configurations and Capabilities

| Spectrometer Type | Spectral Resolution | Typical Application | Advantages / Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Czerny-Turner | Moderate to High | Broad elemental analysis, research applications [4] | Good flexibility and resolution; can be larger in size. |

| Echelle Spectrometer | High | Simultaneous broad-range analysis with high resolution | Compact design for wide spectral coverage; requires cross-dispersion. |

| Compact / Miniaturized | Moderate | Portable and handheld LIBS systems [6] | Enabled by advancements in miniaturization for field use. |

The choice of spectrometer is a critical trade-off between spectral resolution, wavelength coverage, and physical size. Broadband high-resolution spectrometers, developed and commercialized in the early 2000s, were a key innovation that allowed LIBS systems to maintain sensitivity to chemical elements even at low concentrations [4]. For handheld devices dominating the market, the challenge and achievement have been to miniaturize spectrometer components without completely sacrificing analytical performance, thus enabling real-time, on-site elemental analysis [6]. The spectral window covered (e.g., from deep UV to near-IR) determines which elemental emission lines can be observed.

Detectors

Detectors capture the dispersed light from the spectrometer and convert photons into an electrical signal that is digitized and processed.

Common Detector Types and Characteristics in LIBS

| Detector Type | Principle | Key Features | Suitability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intensified CCD (ICCD) | Gated intensifier + CCD | High sensitivity, ultrafast gating (ns), time-resolved analysis [1] | Essential for rejecting initial plasma continuum; useful for plasma diagnostics. |

| Non-Intensified CCD/CMOS | Semiconductor photodiodes | Lower cost, rugged, no gating required | Often used with fs-LIBS where plasma continuum is weak, or in portable systems. |

The Intensified CCD (ICCD) is a cornerstone of traditional ns-LIBS. Its ability to be electronically gated is crucial. By activating the detector with a precise time delay (from tens of nanoseconds to several microseconds) after the laser pulse, the initial intense continuum radiation from the hot plasma can be excluded. This allows the detector to collect only the sharper atomic and ionic line emissions that appear as the plasma cools, dramatically improving the signal-to-noise ratio [1]. The temporal resolution of LIBS plasma, which is on the order of a few nanoseconds for ns-laser pulses, makes this gating capability essential [1]. For fs-LIBS, where the plasma continuum is inherently weaker, non-intensified CCD or CMOS detectors can be sufficient, simplifying the system and reducing cost.

Advanced Methodologies and Protocols

Experimental Workflow for Material Analysis

The following diagram outlines the generalized experimental workflow for a LIBS analysis, from sample preparation to data interpretation.

Protocol: Analysis of a Metallic Alloy Using a Bench-Top LIBS System

1. Sample Preparation:

- Objective: Obtain a flat, clean surface for consistent laser ablation.

- Procedure: If the sample is a bulk metal, polish the surface with progressively finer grit sandpapers (e.g., from 400 to 1200 grit) to create a uniform surface. Clean the polished surface with a solvent like isopropanol and allow it to dry to remove any residues or particles [7].

2. Instrument Setup:

- Laser Alignment: Focus the laser pulse (e.g., from a Nd:YAG laser at 1064 nm) onto the sample surface using a plano-convex lens (e.g., 20 cm focal length). The focus should be slightly below the surface to maximize ablation efficiency and stabilize the plasma.

- Spectrometer & Detector Configuration:

- Set the spectrometer to cover a relevant wavelength range (e.g., 200 - 500 nm for most metals).

- For an ICCD detector, set the delay time (td) and gate width (tw). A typical starting point is a delay of 1 µs and a gate width of 5 µs to avoid the strong plasma continuum. Adjust based on the observed signal-to-noise ratio [5].

3. Data Acquisition:

- Set the laser pulse energy (e.g., 50 mJ). Use a laser fluence that is above the ablation threshold but avoids excessive sample damage or signal saturation.

- Position the sample on a motorized stage to allow for analysis at multiple fresh spots.

- Acquire spectra from multiple laser pulses (e.g., 10-50 pulses per spot) and average them to improve precision.

4. Data Analysis:

- Qualitative Analysis: Identify elemental emission lines in the spectrum by comparing their wavelengths to a database of known atomic lines (e.g., Al I at 396.15 nm, Cu I at 324.75 nm).

- Quantitative Analysis: Construct a calibration curve using certified reference materials with known compositions. Plot the intensity (or integrated area) of a characteristic emission line against the concentration of the corresponding element. Use this curve to determine the concentration of the element in the unknown sample.

Protocol for Nanoparticle-Enhanced LIBS (NELIBS)

NELIBS is a powerful signal enhancement technique where metallic nanoparticles (NPs) deposited on a sample surface significantly increase the emission intensity of the analyte.

1. Nanoparticle Preparation and Deposition:

- Materials: Colloidal suspension of nanoparticles (e.g., 40-50 nm Gold NPs in deionized water) [5].

- Procedure: Deposit a controlled volume (e.g., 5-10 µL) of the NP colloidal solution onto the polished sample surface. Allow the droplet to dry evenly at room temperature, forming a layer of NPs on the analysis area.

2. LIBS Analysis with NPs:

- Use the same laser parameters as for conventional LIBS analysis of the bare sample.

- Focus the laser pulse onto the NP-coated region.

- The localized surface plasmon resonance of the NPs enhances the local electromagnetic field, leading to more efficient ablation and atomization, and a subsequent increase in emission intensity. Studies have reported signal enhancement of a few folds to orders of magnitude for metallic samples in NELIBS compared to standard LIBS [5].

3. Data Comparison:

- Directly compare the spectra acquired from the NP-coated spot with those from the bare sample spot. The enhancement factor for a specific emission line (e.g., Al I) can be calculated as the ratio of the peak intensity with NPs to the peak intensity without NPs.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful execution of LIBS experiments, especially advanced protocols like NELIBS, requires specific reagents and materials.

Key Research Reagents and Materials for LIBS

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Specification / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles (Au NPs) | Signal enhancement in NELIBS [5] | Colloidal suspension, 40-50 nm diameter. Enhances emission via plasmonic effects. |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Calibration and quantitative analysis | Metal alloys, soil, or polymer standards with certified elemental concentrations. |

| Polishing Supplies | Sample preparation for solid targets | Silicon carbide sandpaper (400-1200 grit), polishing cloths, alumina suspension. |

| Calibration Sources | Wavelength calibration of spectrometer | Deuterium-Argon lamps, low-pressure mercury pen lamps. |

| High-Purity Gases | Controlled atmosphere for plasma | Argon purge to improve signal quality for certain elements like carbon [6]. |

Technological Advancements and Future Outlook

The field of LIBS is being rapidly advanced through technological innovation and the integration of sophisticated data processing techniques. A major trend is the miniaturization of LIBS components into portable and handheld devices, which now represent the largest product segment in the market. These devices empower users to perform real-time, on-site elemental analysis in diverse settings, from scrap yards for metal sorting to mining operations for geological surveying [6].

The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) is revolutionizing data analysis. AI algorithms can process vast and complex spectral datasets to identify patterns and correlations that are difficult to discern with traditional methods. For instance, new regression methods that integrate domain knowledge have been shown to outperform standard methods in LIBS quantification tasks, enhancing the accuracy and reliability of element detection and quantification [6]. This is particularly valuable for classifying complex samples like biological tissues or different rock types [8].

Furthermore, advancements in ultra-fast laser technology, particularly the use of femtosecond lasers, are pushing the boundaries of analytical precision. Techniques like plasma-grating induced breakdown spectroscopy (GIBS) have been developed to overcome traditional sensitivity limitations [6]. The use of fs-lasers minimizes thermal damage to the sample and reduces the matrix effect, enabling high-resolution elemental imaging in delicate materials such as pathological tissues with spatial resolution on the scale of micrometers [1]. These combined advancements in hardware and data science are solidifying LIBS's role as a powerful and adaptable analytical technique across an ever-widening range of scientific and industrial applications.

Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS) has emerged as a rapid chemical analysis technique that revolutionizes elemental composition assessment across diverse fields, including pharmaceutical research, material science, and geological exploration [9]. This analytical technique utilizes a highly focused, pulsed laser to instantaneously vaporize a microscopic portion of a sample, creating a high-temperature plasma whose emitted light provides a unique elemental fingerprint [10]. The core advantage of LIBS lies in its capability for virtually sample preparation-free analysis, delivering comprehensive elemental profiles within seconds, a significant improvement over traditional methods requiring hours of preparation [9] [11]. Furthermore, LIBS offers exceptional versatility, capable of analyzing solid, liquid, and gaseous samples across the entire periodic table, with particular excellence in detecting light elements like lithium, beryllium, and carbon that challenge other spectroscopic methods [9] [12]. This protocol provides a detailed, step-by-step guide to the fundamental LIBS process, from laser ablation to spectral interpretation, framed within the context of advanced research applications.

Fundamental Principles and Physics of LIBS

The LIBS process is governed by the fundamental principles of atomic emission spectroscopy. When a high-energy laser pulse is focused onto a sample surface, it delivers an energy density typically ranging from 10⁸ to 10¹¹ watts per square centimeter, sufficient to cause optical breakdown [9]. This process generates a transient plasma with initial temperatures that can exceed 15,000 Kelvin and may reach up to 30,000 K in the earliest stages of its lifetime [9] [11]. At these extreme temperatures, a small mass of the sample—typically on the order of 1-10 micrograms—is ablated and transformed into a plasma containing free electrons, excited atoms, and ions [9] [10].

As the plasma expands and cools over a period of 1-10 microseconds, the excited electrons within the atoms and ions begin to transition from higher energy states to lower, more stable ground states [9] [13]. During these electronic transitions, energy is released in the form of photons. Critically, the wavelength of each emitted photon is inversely proportional to the energy difference between the excited and ground states, following the relation ( E = hc/\lambda ), where ( E ) is the energy difference, ( h ) is Planck's constant, ( c ) is the speed of light, and ( \lambda ) is the wavelength of the emitted photon [12]. Since each element possesses a unique electronic structure with characteristic energy level differences, the emitted wavelengths serve as unique identifiers for the elements present in the sample [11]. The detection and analysis of these characteristic emissions form the basis for both qualitative identification and quantitative determination of elemental composition in LIBS.

Step-by-Step LIBS Process

Laser Ablation and Plasma Formation

The LIBS analytical sequence begins with laser ablation, a process where a focused, high-energy pulsed laser beam interacts with the sample surface. The most commonly employed lasers are Q-switched Nd:YAG lasers operating at their fundamental wavelength of 1064 nm or at harmonic wavelengths such as 532 nm, 355 nm, or 266 nm [10] [13] [12]. These lasers typically generate pulses with durations of 4-15 nanoseconds, pulse energies from 1 mJ to several hundred millijoules, and repetition rates ranging from single shot to over 20 Hz [9] [12]. When this short, intense laser pulse is focused onto a sample, the electric field in the focal region accelerates naturally present ions and those formed via multiphoton interactions, leading to rapid heating and an explosive boiling process that ejects material from the sample surface [13]. This ablation process creates a microscopic crater measuring only 50-500 micrometers in diameter, removing merely 1-10 micrograms of material per pulse, thus preserving sample integrity for subsequent analyses [9].

The ablated material, consisting of atoms, molecules, and particulates, then interacts with the trailing portion of the laser pulse, leading to the formation of a high-temperature plasma plume. The leading edge of the laser pulse creates the initial conditions for ablation, while the remainder of the pulse energy further heats the ejected material, forming a highly energetic plasma [13]. This plasma, initially in a state of severe disequilibrium with temperatures potentially exceeding 50,000 K, contains free electrons, excited atoms, and ions [11] [13]. The specific characteristics of the plasma, including its temperature, electron density, and lifetime, are influenced by multiple factors including the laser parameters (wavelength, pulse duration, energy) and the sample matrix itself [13]. For nanosecond-class lasers, the ablation process is predominantly thermal, involving melting and vaporization, whereas femtosecond lasers produce more mechanical ablation with minimal thermal effects, though their application remains primarily in research due to cost and complexity [13].

Plasma Cooling and Spectral Emission

Following the termination of the laser pulse, the plasma begins to expand and cool rapidly. The initial stage of plasma cooling (typically < 1 microsecond) is dominated by continuum radiation (Bremsstrahlung emission), where highly excited free electrons slow down and emit a broadband background spectrum [11] [13]. As the plasma continues to cool and approaches local thermodynamic equilibrium (LTE)—generally occurring 0.5-1.0 microseconds after plasma formation for a 100-400 mJ plasma—the continuum emission diminishes, and discrete atomic and ionic emission lines begin to dominate the spectral output [13]. During this phase, excited electrons within atoms and ions transition to lower energy states, emitting photons at specific wavelengths characteristic of each element present [9] [12].

The emission characteristics vary throughout the plasma lifetime. Different types of radiation can be observed, including continuum, atomic, ionic, and molecular emissions, each revealing different components of the plasma [10]. The atomic and ionic emissions containing the analytically useful information typically occur after the plasma has sufficiently cooled, usually in the 1-10 microsecond window following the laser pulse [9] [10]. The timing of emission collection is crucial; detectors are often gated to activate after this initial continuum radiation has subsided to improve the signal-to-noise ratio of the discrete elemental emissions [13]. At this stage, the average plasma temperature typically ranges between 7,500-10,000 K, ideal for generating strong elemental emission lines while minimizing background continuum radiation [13].

Light Collection and Dispersion

The emitted light from the plasma is collected through specialized optical systems. In most laboratory and portable LIBS systems, photons are collected by a lens or lens system positioned near the plasma and transmitted to a spectrometer via an optical fiber [9] [12]. An alternative approach, known as stand-off LIBS, is employed in applications such as planetary exploration, where the analyzed sample may be several meters from the instrument. In these configurations, photon emission is captured by a telescope and transmitted to the spectrometer by fiber optics [14] [12]. This stand-off capability has been successfully implemented in NASA's Mars rovers, including the Curiosity rover's ChemCam instrument [14] [12].

The collected light is then dispersed by a spectrometer to separate it into its constituent wavelengths. Various spectrometer types are employed in LIBS systems, with echelle spectrographs being particularly common due to their high resolution across broad wavelength ranges [13] [12]. The spectrometer distributes the light across different spatial locations according to wavelength, creating a detailed spectrum that is recorded using a detector array. Common detectors include charge-coupled devices (CCD), intensified CCD (ICCD) cameras, or photomultiplier tubes, which convert the photon signals into electrical signals for digital processing [9] [10] [13]. These detectors often feature precise timing capabilities (gating) to selectively collect light during the optimal emission window after the continuum background has diminished [13].

Spectral Analysis and Data Interpretation

The final stage of the LIBS process involves spectral analysis and data interpretation to extract meaningful chemical information. The raw spectral data undergoes preprocessing procedures including dark background subtraction, wavelength calibration, ineffective pixel masking, spectrometer channel splicing, and background baseline removal [14]. The resulting spectrum displays intensity as a function of wavelength, with characteristic peaks representing specific electronic transitions of elements present in the sample [11].

Qualitative analysis involves identifying elements by matching observed emission lines to known spectral fingerprints of elements from reference databases [9] [12]. For instance, lithium emits a characteristic line at 670.8 nm, cobalt at 345.4 nm, and nickel at 352.4 nm [9]. Quantitative analysis utilizes the relationship between spectral line intensity and elemental concentration, typically established through calibration with certified reference materials [11] [12]. Advanced chemometric methods are increasingly employed, including machine learning and deep learning algorithms such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs), which can process entire spectral profiles to classify materials or quantify compositions, even overcoming challenges like spectral variations due to changing measurement distances [14] [15]. These multivariate analysis techniques often provide superior accuracy and precision compared to univariate methods that rely on single emission lines [12].

Schematic Diagram of the LIBS Analytical Process

Key Experimental Parameters and Protocols

Critical LIBS Operational Parameters

Successful implementation of LIBS requires careful optimization of several critical operational parameters that significantly influence analytical performance. The table below summarizes these key parameters and their typical values or considerations for robust method development.

Table 1: Key Operational Parameters in LIBS Analysis

| Parameter Category | Specific Parameter | Typical Values / Considerations | Impact on Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Laser Properties | Wavelength | 1064 nm (fundamental), 532 nm, 355 nm, 266 nm (harmonics) | Shorter wavelengths often provide better ablation efficiency and smaller spot sizes [10] [13] |

| Pulse Duration | Nanosecond (most common), Picosecond, Femtosecond | ns-pulses: thermal ablation; fs-pulses: non-thermal, minimal heat-affected zone [13] | |

| Pulse Energy | 1 mJ to hundreds of mJ | Higher energy increases plasma temperature and emission intensity, but may increase fractionation [9] [13] | |

| Spot Size | 50-500 μm diameter | Smaller spots enable higher spatial resolution; larger spots provide better sampling volume [9] [12] | |

| Temporal Parameters | Gate Delay | 0.5-1.0 μs (for higher energy lasers) | Time between laser pulse and start of signal collection; optimizes signal-to-background ratio [13] |

| Gate Width | 1-10 μs | Duration of signal collection; affects signal intensity and spectral resolution [14] | |

| Sample Considerations | Surface Condition | Fresh, representative surface | LIBS analyzes only the surface; weathered or contaminated surfaces yield non-representative results [9] |

| Homogeneity | Homogeneous vs. heterogeneous | Heterogeneous samples require multiple analysis points for representative bulk composition [9] [12] | |

| Environmental Factors | Atmosphere | Air, Argon, Helium, or Vacuum | Ambient atmosphere affects plasma formation and emission characteristics [13] |

| Distance | Contact to several meters (stand-off) | Distance variations alter laser spot size, energy distribution, and collection efficiency [14] |

Standard LIBS Analysis Protocol

The following protocol outlines a standardized approach for LIBS analysis, adaptable to various sample types and instrument configurations.

Protocol: LIBS Elemental Analysis of Solid Samples

1. Sample Preparation

- For solid samples, ensure a fresh, representative surface is available for analysis. If necessary, clean the surface with solvent or gently abrade to remove oxidation or contamination layers [9] [12].

- For powdered materials, consider compression into pellets using a standardized compression molding process to enhance homogeneity and reproducibility [14].

- Mount the sample securely to minimize movement during analysis, particularly important for automated mapping or depth profiling studies.

2. Instrument Setup and Calibration

- Power up the LIBS instrument, laser system, and detector, allowing sufficient warm-up time for source stability (typically 15-30 minutes).

- If quantitative analysis is required, select appropriate certified reference materials (CRMs) that closely match the sample matrix to establish calibration curves [9] [12].

- Set the laser parameters based on sample properties and analysis requirements:

- Wavelength selection: UV wavelengths (266 nm, 355 nm) for improved spatial resolution and reduced thermal effects; IR wavelengths (1064 nm) for robust plasma formation [13].

- Pulse energy: Adjust to achieve sufficient signal without excessive sample damage (typical range: 1-100 mJ) [9].

- Spot size: Select based on spatial resolution requirements and heterogeneity (typical range: 50-500 μm) [9].

- Optimize temporal parameters:

3. Spectral Acquisition

- Position the sample at the focal point of the laser using the instrument's viewing system or range-finding capability.

- For heterogeneous materials, acquire multiple spectra from different locations (typically 10-100 spots) to obtain representative sampling [12].

- For each analysis point, acquire multiple laser pulses (typically 3-10 pulses) at the same location if depth profiling is desired, or use single pulses at different locations for bulk composition assessment.

- For each spectrum, record the complete emission wavelength range (typically 200-900 nm) with sufficient spectral resolution to resolve element-specific lines [14].

4. Data Processing and Analysis

- Apply preprocessing algorithms to raw spectra:

- Dark background subtraction to remove detector noise [14].

- Wavelength calibration using known emission lines from standard materials [14].

- Background baseline correction to remove continuum background contributions [14].

- Normalization to a reference line or total intensity to minimize pulse-to-pulse variations [12].

- For qualitative analysis: Identify elements by matching characteristic emission lines to reference spectral libraries [9] [11].

- For quantitative analysis: Apply univariate calibration (using intensity-concentration relationship of specific lines) or multivariate calibration (using full spectral information with methods like Partial Least Squares Regression) [12].

5. Quality Control and Validation

- Analyze quality control samples (CRMs not used in calibration) at regular intervals to verify analytical accuracy.

- Monitor key performance metrics including precision (typically ±2-5% RSD for major elements), detection limits (ppm to sub-ppm for many elements), and analytical accuracy [9].

- For research publications, include comprehensive method documentation detailing all instrument parameters, sample preparation procedures, and data processing methods.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential LIBS Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Materials for LIBS Analysis

| Category | Item | Specification / Purpose | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calibration Standards | Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Matrix-matched to samples with certified elemental concentrations | Essential for quantitative analysis; should cover expected concentration ranges of analytes [9] [12] |

| Standard Reference Materials | National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) or equivalent | Used for method validation and quality control procedures | |

| Sample Preparation | Pellet Press | Hydraulic or manual press with die sets | For compacting powdered samples into homogeneous pellets; typically applies 5-20 tons pressure [14] |

| Binding Agents | High-purity cellulose, polyvinyl alcohol, or wax powders | For enhancing cohesion of powdered samples during pelletization; should be spectroscopically pure | |

| Instrument Calibration | Wavelength Calibration Standards | Mercury/argon lamps or certified spectral calibration slides | For accurate wavelength assignment across the spectral range [14] |

| Response Calibration Standards | NIST-traceable intensity standards | For correcting instrument response function across wavelength range | |

| Quality Control | Quality Control Samples | Certified materials with known compositions, different from calibration set | For verifying analytical accuracy and precision during analysis sequences |

| Sample Mounting Materials | High-purity graphite holders, glass slides, or custom fixtures | For secure and reproducible sample positioning during analysis |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

LIBS technology has evolved beyond basic elemental analysis to enable sophisticated applications across diverse scientific disciplines. In planetary exploration, LIBS instruments onboard NASA's Curiosity and Perseverance rovers and China's Zhurong rover have demonstrated the capability for stand-off analysis of geological samples at distances of several meters, providing crucial geochemical data for understanding Martian geology [14] [15] [12]. For pharmaceutical analysis, LIBS offers rapid quality control of raw materials and finished products, with the ability to detect metallic impurities and verify composition without extensive sample preparation [16]. The mining and geology sectors utilize portable LIBS systems for real-time field analysis, enabling immediate decisions during exploration and grade control operations with analysis times of 30-60 seconds per measurement point [9].

The integration of artificial intelligence with LIBS represents the most significant advancement in the field. Deep learning algorithms, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs), have demonstrated remarkable capabilities in processing complex LIBS spectra, automatically identifying patterns, and overcoming traditional challenges such as the "distance effect" where spectral profiles change with varying measurement distances [14] [15]. Recent research has shown that CNN models with optimized spectral sample weighting can achieve classification accuracies exceeding 92% for geochemical samples analyzed at multiple distances, significantly improving upon traditional chemometric methods [14]. These AI-enhanced LIBS systems are increasingly incorporated into industrial automation and quality control processes, with cloud connectivity enabling real-time data sharing and predictive maintenance alerts [16]. As LIBS technology continues to mature, its combination with complementary analytical techniques such as Raman spectroscopy and the development of standardized calibration protocols across industries will further expand its applications in research and industrial settings [16].

Historical Development and Technological Evolution of LIBS

Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS) has emerged as a robust analytical technique for elemental analysis, experiencing significant technological evolution since its inception. This article traces the historical development of LIBS and details its technological advancements, focusing on its principles, instrumentation, applications, and experimental protocols. The technique's journey from a laboratory curiosity to a tool deployed on Mars exemplifies its growing importance in scientific research and industrial applications. LIBS is now recognized as a "future superstar" of chemical analysis due to its minimal sample preparation requirements and capability for real-time, multi-element analysis [17].

The core principle of LIBS involves using a high-energy laser pulse to generate a micro-plasma on the sample surface, with subsequent spectral analysis of the emitted light to determine elemental composition. This simple yet powerful concept has enabled LIBS to find applications across diverse fields including microbiology, environmental science, pharmaceutical analysis, and geology. The recent integration of machine learning with LIBS has further enhanced its analytical capabilities, addressing earlier limitations and opening new frontiers for quantitative analysis [17].

Historical Development

The foundation of LIBS was laid with the development of lasers in the 1960s, but the technique gained significant research momentum starting in the 1980s. Annual publications and patents containing "LIBS" or "laser-induced breakdown" in their titles have grown dramatically from near zero through the 1970s to approximately 300-400 per year currently [13]. This growth pattern follows a logistic function, suggesting the technology is reaching maturity while continuing to expand into new application areas.

The early 2000s marked a significant turning point for LIBS, with the technique transitioning from primarily academic research to commercial implementation. Major manufacturers began producing commercially available LIBS systems, indicating the technology's maturation and growing acceptance in analytical laboratories [13]. This period also saw LIBS being incorporated into undergraduate teaching and research programs, promoting awareness and familiarity with the technique among emerging scientists [18].

A landmark achievement in LIBS history was the deployment of a LIBS instrument on the Mars Science Laboratory rover, demonstrating the technique's capability for in-situ analysis in extreme environments [19]. This success highlighted LIBS's advantages for space exploration and other challenging applications where traditional analytical methods are impractical.

Fundamental Principles and Physics

Basic LIBS Process and Plasma Formation

The LIBS technique operates through a sequence of physical processes that convert laser energy into analytical information. When a high-energy pulsed laser is focused onto a sample surface, several interconnected events occur in rapid succession. The initial portion of the laser pulse penetrates the sample, causing ablation through thermal and non-thermal mechanisms that eject a small quantity of material [11] [13]. For nanosecond-class lasers, this process involves substantial heating and melting of the sample due to the laser pulse duration being significantly longer than characteristic lattice vibration times in solids [13].

The ejected material subsequently interacts with the trailing portion of the laser pulse, forming a highly energetic plasma with temperatures that can exceed 30,000K in its early stages [11]. This laser-induced plasma contains free electrons, excited atoms, and ions, creating the conditions for elemental emission. The plasma cools rapidly after the laser energy terminates, and during this cooling process, electrons in excited atoms and ions transition to lower energy states, emitting light at characteristic wavelengths [11]. The collected emission spectrum provides a unique fingerprint of the sample's elemental composition, with each element producing distinctive spectral peaks that enable both qualitative identification and quantitative analysis [11].

Figure 1: Fundamental LIBS Process Flow Diagram

Laser-Matter Interaction Mechanisms

The interaction between laser pulses and sample materials varies significantly based on laser parameters, particularly pulse duration. Nanosecond lasers (typically 4-8 ns pulse duration) produce thermally dominated ablation characterized by explosive boiling that ejects both liquid and solid-phase particles, creating crater-like structures on the sample surface [13]. The resulting plasma formation is influenced by laser wavelength, with infrared wavelengths generally producing more robust plasmas than ultraviolet wavelengths due to enhanced absorption in the forming plasma [13].

In contrast, femtosecond laser ablation operates through fundamentally different mechanisms. The extremely short pulse durations (on the order of 10⁻¹⁵ seconds) prevent significant heat transfer, minimizing sample melting and creating more precise ablation craters with minimal residual heat-affected zones [13]. This non-thermal ablation reduces problems of preferential desorption and non-stoichiometric ablation, though the higher cost and complexity of femtosecond lasers have limited their widespread adoption in commercial LIBS systems [13].

Technological Evolution and Instrumentation

LIBS System Components and Configurations

A typical LIBS system consists of several key components: a pulsed laser, beam delivery optics, sample stage, light collection optics, a wavelength-sensitive detector, and data processing electronics [13]. The laser source is most commonly an Nd:YAG laser operating at its fundamental wavelength of 1064 nm or harmonics (532, 355, or 266 nm), selected based on application requirements and cost considerations [20] [13].

Detection systems have evolved significantly, with modern LIBS instruments employing intensified CCD detectors, electron-multiplying CCDs, or photomultiplier tubes with integrating electronics [13]. These detectors often incorporate time-gating capabilities, allowing collection of emission signals after the initial continuum radiation has decayed, when the plasma approaches local thermodynamic equilibrium and characteristic atomic emissions dominate [13]. This temporal resolution is crucial for optimizing signal-to-noise ratios and improving detection limits.

Advancements in LIBS Performance

Recent technological advancements have addressed several traditional limitations of LIBS, particularly regarding quantification capabilities and measurement precision. The development of double-pulse LIBS techniques, where two sequential laser pulses interact with the sample, has demonstrated significant improvements in detection limits by enhancing ablation efficiency and plasma conditions [13]. Additionally, the combination of LIBS with other analytical techniques such as Raman spectroscopy or laser-induced fluorescence has expanded its analytical capabilities for specific applications [18].

The emergence of handheld LIBS instruments represents another significant advancement, enabling field-based analysis for applications including geochemical fingerprinting, forensic science, and industrial quality control [18]. These portable systems maintain analytical performance while offering the convenience of in-situ measurement, with potential impacts comparable to those achieved by handheld XRF instruments [18].

Table 1: Evolution of LIBS Technology and Performance Characteristics

| Time Period | Laser Technology | Detection Systems | Key Applications | Limits of Detection |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980s-1990s | Basic Nd:YAG lasers, primarily 1064 nm | Non-gated detectors, photomultiplier tubes | Laboratory-based elemental analysis | High ppm range for most elements |

| 2000-2010 | Harmonic generation (532, 355, 266 nm), improved stability | Intensified CCD cameras, initial portable systems | Environmental monitoring, industrial sorting | Mid to low ppm range |

| 2011-Present | Compact diode-pumped lasers, handheld systems | High-resolution spectrometers, advanced gating | Mars exploration (Curiosity rover), field analysis | Low ppm to ppb for some elements |

| Future Trends | Femtosecond lasers, hybrid systems | Hyperspectral imaging, AI-enhanced analysis | Medical diagnostics, pharmaceutical quality control | Improved precision and reliability |

Applications in Research and Industry

Biological and Medical Applications

LIBS has emerged as a valuable tool for detecting and identifying microorganisms, including bacteria, molds, yeasts, and spores [20]. The technique's ability to provide rapid, elemental-based identification of pathogens has significant implications for medical diagnostics, food safety, and environmental monitoring. LIBS has successfully detected foodborne pathogens such as Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium and Escherichia coli, enabling quicker response to contamination events compared to traditional microbiological methods [20].

In medical science, LIBS shows promise for rapid diagnosis of infectious diseases like tuberculosis, potentially reducing the time between sample collection and treatment initiation [20]. The technique's minimal sample preparation requirements and ability to analyze various sample types (blood, sputum, urine) make it suitable for clinical settings where speed and simplicity are essential.

Pharmaceutical and Material Science Applications

The pharmaceutical industry has adopted LIBS for various applications, including active ingredient distribution analysis, impurity detection, and quality control of raw materials and finished products [21]. When combined with artificial intelligence, particularly deep learning algorithms, LIBS can automatically identify complex patterns in spectral data, enhancing its capabilities for drug development and analysis [21]. The technique's sensitivity to light elements including carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, and oxygen makes it particularly valuable for organic compound analysis in pharmaceutical contexts.

LIBS has also proven valuable for geochemical fingerprinting and analysis of conflict minerals, where it can verify the geographic origin of materials based on their unique elemental signatures [18]. This application leverages the Earth's crustal heterogeneity, with mineral compositions reflecting their specific geographic origins, enabling discrimination between samples from different mining locations [18].

Table 2: LIBS Applications Across Different Fields

| Field | Specific Applications | Key Advantages | Representative Samples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microbiology | Pathogen detection, bacterial discrimination, microbial identification | Rapid analysis, minimal sample preparation, no culture required | Bacteria, molds, yeasts, spores |

| Pharmaceuticals | Drug composition analysis, impurity detection, quality control | Sensitivity to light elements, minimal sample preparation | Tablets, powders, raw materials |

| Environmental Science | Soil analysis, water quality monitoring, air particulate matter | Field deployable, real-time monitoring, multi-element capability | Soils, sediments, water, aerosols |

| Geology | Geochemical fingerprinting, conflict mineral identification, ore grading | Handheld operation, light element sensitivity, rapid analysis | Rocks, minerals, ores, soils |

| Forensic Science | Glass analysis, paint characterization, ink and paper analysis | Minimal destruction, spatial resolution, broad element coverage | Glass fragments, paint chips, documents |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard LIBS Analysis Protocol

Protocol Title: Standard Operating Procedure for LIBS Elemental Analysis

Principle: A high-energy pulsed laser is focused onto the sample surface to create a transient plasma. The collected light from this plasma is spectrally resolved to identify elemental composition based on characteristic emission lines [20] [11].

Materials and Equipment:

- Pulsed laser system (typically Nd:YAG, 1064 nm or harmonics)

- Spectrometer with broadband detection capability

- Timing electronics for laser and detector synchronization

- Sample presentation stage

- Optical components for laser focusing and light collection

- Computer with data acquisition and analysis software

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation:

- For solid samples: Present with flat, clean surface. Minimal preparation typically required.

- For powder samples: May be pressed into pellets or analyzed loose.

- For liquid samples: Typically analyzed by drying droplets on substrates or using liquid jets.

Instrument Setup:

- Align laser focusing optics to achieve required power density (typically 1-10 GW/cm²).

- Adjust light collection optics to maximize signal from plasma region.

- Set spectrometer parameters (wavelength range, resolution) appropriate for target elements.

- Configure timing parameters (laser pulse duration, detector delay time, gate width).

Data Acquisition:

- Position sample at laser focus point.

- Initiate laser firing sequence (single shots or bursts).

- Collect emission spectra from multiple locations for representative analysis.

- Record background spectra for subtraction if required.

Data Analysis:

- Identify elemental emission lines through spectral database matching.

- Apply calibration models for quantitative analysis.

- Utilize chemometric methods for complex sample discrimination.

Quality Control:

- Analyze certified reference materials with similar matrix to validate accuracy.

- Monitor signal stability through repeated analysis of control samples.

- Verify detector performance using standard light sources.

Microbial Sample Analysis Protocol

Protocol Title: LIBS Analysis for Bacterial Discrimination and Identification

Special Considerations: Microbial samples typically require deposition on specialized substrates and may need pretreatment for optimal analysis [20].

Sample Preparation Variations:

- Filter Deposition: Pass liquid suspensions through membrane filters, analyze filters directly.

- Agar Substrates: Transfer colonies directly from agar plates to suitable substrates.

- Direct Analysis: Analyze bacterial colonies or biofilms growing on surfaces without transfer.

Experimental Parameters:

- Laser wavelength: 266 nm often preferred for reduced background from organic matrix

- Laser energy: Typically 10-50 mJ/pulse

- Detector delay: 1-2 μs to reduce continuum background

- Number of spectra: 30-50 per sample for statistical significance

Data Analysis Approach:

- Utilize multivariate statistical methods (PCA, LDA, PLS-DA) for discrimination

- Employ machine learning algorithms for classification

- Develop spectral libraries for known organisms for future identification

Current Challenges and Future Perspectives

Analytical Challenges and Standardization

Despite significant advancements, LIBS still faces challenges that limit its widespread adoption for routine quantitative analysis. The technique has been traditionally considered only semi-quantitative due to issues with reproducibility, precision, and matrix effects [19] [17]. These limitations stem from the complex nature of laser-matter interactions and plasma formation processes, which are influenced by numerous experimental parameters [19].

A critical challenge for the LIBS community is the lack of standardization across different instruments and laboratories. Interlaboratory comparisons have demonstrated significant variations in results, even when analyzing identical samples, highlighting the influence of both experimental parameters and data processing methods [19]. This variability is reflected in reported limits of detection that can span several orders of magnitude for the same element [19]. Addressing these challenges requires developing standardized protocols, reference materials, and data processing approaches to improve reproducibility and comparability between different LIBS systems.

Machine Learning Integration

The integration of machine learning with LIBS represents one of the most promising avenues for addressing the technique's quantitative challenges [17]. Machine learning methods can automatically extract meaningful information from LIBS spectra, reducing the need for subjective interpretation and manual feature selection [17]. These approaches have demonstrated potential for mitigating matrix effects, self-absorption, signal uncertainty, and spectral line interference – all traditional limitations of LIBS analysis [17].

Initial applications employed linear methods such as multiple linear regression, principal component regression, and partial least squares, which provide good interpretability but may struggle with complex, nonlinear data [17]. More recent approaches have incorporated nonlinear methods including support vector regression, kernel extreme learning machines, and multilayer perceptrons to better capture data nonlinearity and improve quantitative accuracy [17]. The most advanced implementations utilize deep neural networks to extract high-level abstract features from LIBS data, potentially achieving predictive performance beyond traditional methods [17].

Figure 2: Machine Learning Integration in LIBS Analysis

Emerging Applications and Future Directions

Future developments in LIBS technology will likely focus on improving analytical performance while expanding application areas. The continued miniaturization of LIBS systems will enable new field applications in environmental monitoring, planetary exploration, and point-of-care medical diagnostics [18] [19]. Combining LIBS with complementary analytical techniques through data fusion strategies represents another promising direction, potentially providing more comprehensive material characterization than any single technique alone [17].

The development of laser ablation molecular isotopic spectrometry (LAMIS) extends LIBS capabilities to isotopic analysis by leveraging larger isotopic shifts in molecular spectra compared to atomic emissions [18]. This approach could enable LIBS-based measurement of isotope ratios in geomaterials without requiring ultrahigh-resolution spectrometers, with potential applications in geochronology and nuclear materials analysis [18].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for LIBS Applications

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials | Calibration and validation | Matrix-matched standards essential for quantitative analysis; available as powders, pellets, or solid disks |

| Sample Preparation Tools | Pellet presses, filters, substrates | Preparation of powders into pellets improves reproducibility; membrane filters used for liquid sample concentration |

| Laser Accessories | Harmonic generators, beam expanders, focusing lenses | Wavelength selection affects plasma characteristics; focusing conditions influence ablation efficiency |

| Spectrometer Calibration Sources | Wavelength calibration, intensity correction | Mercury-argon lamps common for wavelength calibration; standard light sources for intensity correction |

| Specialized Sampling Chambers | Controlled atmosphere analysis | Gas-tight chambers enable analysis under inert gases or reduced pressure to enhance signal for specific elements |

| Data Processing Software | Spectral analysis, chemometrics, machine learning | Commercial and custom software packages for data preprocessing, multivariate analysis, and machine learning implementation |

Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS) is an analytical technique that uses a high-powered laser pulse to create a microplasma on the sample surface. The light emitted from this plasma is then analyzed to determine the elemental composition of the sample [22] [23]. This technique has gained significant attention for its rapid analysis capabilities and minimal sample preparation requirements. LIBS is also known by the term Laser Optical Emission Spectrometry (Laser-OES), which positions it within the broader family of optical emission spectroscopy techniques that include Spark-OES, Arc-OES, and ICP-OES [24].

Traditional elemental analysis methods include Inductively Coupled Plasma Atomic Emission Spectroscopy (ICP-AES, also commonly referred to as ICP-OES), Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS), and X-ray Fluorescence (XRF). Each of these techniques has established itself in various analytical domains but comes with specific operational requirements and limitations. ICP-AES excels in sensitivity and multi-element detection but requires extensive sample preparation [22]. AAS is known for its precision in trace element analysis but typically handles only one element at a time. XRF provides non-destructive analysis but struggles with light elements and has limited sensitivity for trace-level detection [25] [26].

This application note provides a detailed comparison of these techniques, focusing on the operational advantages of LIBS, particularly in contexts where speed, portability, and minimal sample preparation are critical.

Technical Comparison of Analytical Methods

The following table summarizes the key technical characteristics of LIBS compared to ICP-AES, AAS, and XRF.

Table 1: Technical comparison of LIBS, ICP-AES, AAS, and XRF

| Parameter | LIBS | ICP-AES | AAS | XRF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation | Minimal or none [22] [23] | Extensive (typically digestion and dilution) [22] | Extensive (digestion needed for solids) | Minimal (non-destructive) [25] |

| Analysis Speed | Very fast (seconds) [27] | Moderate to fast (minutes including preparation) | Slow (single element at a time) | Fast (seconds to minutes) [25] |

| Detection Limits | ppm range [22] [26] | ppb to ppt range [22] | ppb range | ppm range [25] |

| Elemental Coverage | Wide range (including light elements Li, Be, B) [25] | Very wide range | Limited by light source | Limited for light elements (Z<11) [25] |

| Sample Throughput | High (rapid in-situ analysis) | High (after preparation) | Low | High [25] |

| Portability | Excellent (handheld systems available) [22] [27] | Poor (lab-bound) | Poor (lab-bound) | Good (handheld systems available) [25] |

| Sample State Compatibility | Solids, liquids, gases [22] | Primarily liquids | Primarily liquids | Primarily solids [25] |

| Sample Damage | Minimal (micro-ablation) [27] | Destructive | Destructive | Non-destructive [25] |

| Operational Costs | Low (no consumables) [27] | High (argon gas, tubes) | Moderate (lamp sources) | Low [25] |

Key Advantages of LIBS Over Traditional Techniques

Compared to ICP-AES: LIBS eliminates the need for sample digestion and the use of expensive argon gas, significantly reducing both preparation time and operational costs [22] [27]. This allows for direct analysis of solids in their native state, which is particularly advantageous for field applications and industrial process control.

Compared to AAS: Unlike AAS, which is limited to single-element analysis, LIBS provides simultaneous multi-element detection capabilities [23]. This dramatically improves analytical throughput when comprehensive elemental characterization is required.

Compared to XRF: LIBS demonstrates superior performance for light element detection (lithium, beryllium, boron, carbon) that are challenging for conventional XRF systems [25] [27]. This capability is particularly valuable in industries such as aerospace and battery manufacturing where these elements are critical.

Experimental Protocols

Generic LIBS Analytical Protocol

Scope: This protocol describes the standard procedure for elemental analysis of solid samples using a handheld or benchtop LIBS system.

Equipment and Reagents:

- LIBS analyzer (handheld or benchtop)

- Sample presentation stage (if using benchtop system)

- Compressed air source for lens cleaning

- Standard reference materials for calibration (when quantitative analysis is required)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: For solid samples, ensure the analysis surface is accessible. No cutting, polishing, or digestion is typically required. Remove gross contamination if present. For loose powders, consider pressing into pellets for improved reproducibility [26].

- Instrument Calibration: Verify instrument calibration using manufacturer-supplied standards. For quantitative analysis, establish a calibration curve using certified reference materials that match the sample matrix [26].

- Analysis: Position the analyzer probe perpendicular to and in direct contact with the sample surface. For handheld units, apply consistent pressure to maintain contact. Fire the laser for the predetermined number of pulses (typically 10-50 pulses per spot) [27].

- Data Collection: The system will automatically collect spectral emissions from the generated plasma. Multiple shots may be averaged to improve signal-to-noise ratio.

- Data Interpretation: Use built-in software algorithms to identify elements based on characteristic emission lines and calculate concentrations based on calibration curves.

- Quality Control: Analyze a known standard after every 10-20 samples to verify calibration stability. Clean the instrument window regularly with compressed air to prevent sample carryover.

Applications: This general protocol is applicable to various sample types including metals, soils, polymers, and biological materials with minimal modifications.

Specialized Protocol: LIBS Analysis of Gold in Ore Samples

Background: Traditional analysis of gold in ores requires fire assaying followed by AAS or ICP-AES analysis, which is time-consuming and laboratory-bound. LIBS offers rapid screening capability with minimal sample preparation [26].

Specific Equipment:

- LIBS system with enhanced sensitivity for gold (267.59 nm emission line)

- Pellet press for powder samples

- Synthetic standard samples with known gold concentrations (0.5-100 ppm) in relevant matrices

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Grind representative ore samples to fine powder (<100 μm). Mix thoroughly to ensure homogeneity. Press approximately 5g of powder into a pellet at 10-15 tons pressure.

- Matrix-Matched Calibration: Establish separate calibration curves for iron-rich (>15% Fe) and silicon-rich (<5% Fe) matrices, as the gold signal intensity varies with matrix composition [26].

- Analysis Parameters: Use 30-50 laser pulses per spot at 1064 nm wavelength. Analyze multiple spots (10-20) per pellet to account for potential heterogeneity of gold distribution.

- Signal Normalization: Normalize the gold line intensity (Au I 267.59 nm) to the integrated spectrum intensity or the spectral background close to the gold line to improve regression fit [26].

- Data Interpretation: Use the appropriate calibration curve (Fe-rich or Si-rich) based on the iron content determined from the continuum emission.

Performance Metrics: With this protocol, limits of detection of 0.8 ppm for Si-rich samples and 1.5 ppm for Fe-rich samples can be achieved, nearly meeting the needs of the mining industry for gold determination (~1 ppm) [26].

Specialized Protocol: LIBS for Bitumen Content in Oil Sands

Background: Traditional Dean-Stark extraction for bitumen content determination in oil sands takes several hours to complete. LIBS provides rapid alternative with minimal sample preparation [26].

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Collect representative oil sands samples. No additional preparation is required, though crushing oversized material improves reproducibility.

- Qualitative Screening: Perform initial LIBS analysis to identify spectral features correlated with bitumen content, particularly carbon and hydrogen lines.

- Multivariate Calibration: Use Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression or other multivariate algorithms to correlate spectral features with bitumen content determined by reference methods.

- Validation: Validate the model using independent sample sets not included in the calibration.

Performance: This approach has demonstrated prediction averaged absolute error of <1% for bitumen content, representing a viable alternative to traditional methods [26].

Visual Workflows and Technical Diagrams

LIBS Analytical Process Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental process of Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy analysis:

Technique Selection Decision Framework

This decision tree guides the selection of the most appropriate analytical technique based on application requirements:

Advanced Applications and Recent Developments

Machine Learning Enhancement of LIBS

Traditional LIBS quantification has been challenged by matrix effects and signal variability. Recent advances combine LIBS with machine learning to address these limitations [17]. The integration of algorithms such as Partial Least Squares Regression (PLSR), Support Vector Regression (SVR), and neural networks has significantly improved the accuracy and reliability of LIBS quantitative analysis [28] [17].

Table 2: Machine learning approaches for enhancing LIBS performance

| ML Method | Application | Benefit | Reference Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| PLSR | Quantitative analysis of heavy metals in aerosols | Improved calibration model accuracy | [28] |

| Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LGBM) | Spectral data screening | Superior performance compared to standard deviation method | [28] |

| Back Propagation Neural Network | Soil analysis and stream sediment analysis | Improved repeatability and accuracy | [17] |

| Transfer Learning | Analysis under extreme conditions | Adaptation to new tasks with limited data | [17] |

| Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) | Feature optimization in multivariate models | Enhanced model performance by selecting optimal variables | [28] |

Novel LIBS Configurations

Advanced LIBS configurations continue to emerge, addressing specific limitations of traditional LIBS:

Plasma-Grating-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (GIBS): This novel technique uses a plasma grating induced by nonlinear interaction of multiple femtosecond filaments to overcome the laser intensity clamping effect. GIBS enhances signal intensity by more than three times and extends plasma lifetime compared to conventional LIBS [23].

Femtosecond LIBS (fs-LIBS): Using femtosecond laser pulses instead of nanosecond pulses reduces the plasma shielding effect, leading to improved reproducibility and signal-to-noise ratio [23].

Spectral Screening-Assisted LIBS: Combining LIBS with effective spectral selection algorithms improves quantitative analysis of heavy metal elements in challenging matrices like liquid aerosols [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential components for LIBS research and application

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Portable LIBS Analyzer | Field-based elemental analysis | Handheld units available for in-situ measurements; no radiation concerns unlike XRF [27] |

| Benchtop LIBS System | Laboratory-based high-precision analysis | Typically offers higher spectral resolution and better precision than handheld units |

| Matrix-Matched Reference Materials | Calibration and validation | Critical for quantitative analysis; should match sample composition [26] |

| Pellet Press | Sample preparation for powders | Creates uniform surfaces for improved analytical reproducibility [26] |

| Machine Learning Software | Data analysis and modeling | Essential for advanced quantification; PLSR, neural networks, etc. [28] [17] |

| Custom Sampling Chambers | Analysis of specialized samples | Enable analysis of aerosols, liquids, and other challenging sample types [28] |