GC-MS in Forensic Science: Principles, Applications, and Advanced Methodologies for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive examination of Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) as a cornerstone analytical technique in forensic science.

GC-MS in Forensic Science: Principles, Applications, and Advanced Methodologies for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) as a cornerstone analytical technique in forensic science. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the fundamental principles of GC-MS operation, from sample separation to mass spectral detection. It details cutting-edge methodological applications in analyzing seized drugs, toxicological samples, and trace evidence like fibers. The content further offers practical guidance on troubleshooting common issues, optimizing performance, and validates the technique through comparisons with advanced methods like comprehensive two-dimensional GC (GC×GC-MS), all within the critical context of legal admissibility standards such as the Daubert and Frye criteria.

The GC-MS Foundation: Core Principles and Instrumentation for Forensic Analysis

Hyphenated techniques represent a paradigm shift in analytical science, born from the powerful synergy of combining separation methodologies with advanced spectroscopic detection technologies. The term "hyphenation" was formally introduced by Hirschfeld to describe the on-line coupling of a separation technique with one or more spectroscopic detection techniques [1] [2]. This integration creates an analytical system where the whole becomes significantly greater than the sum of its parts. By marrying the separation capabilities of chromatography with the identification power of spectroscopy, hyphenated techniques provide researchers with an unparalleled ability to characterize complex mixtures in a single, automated workflow [3].

In the specific context of forensic science, where samples are often complex mixtures and evidentiary value hinges on unambiguous identification, these techniques have become indispensable. They have evolved from novel approaches to fundamental tools that now form the analytical backbone of modern forensic laboratories, particularly in the realm of controlled substance analysis [4]. The core principle is elegant in its simplicity yet profound in its impact: a chromatograph (such as a Gas Chromatograph) separates the components of a mixture in time, and a spectrometer (such as a Mass Spectrometer) then provides definitive structural information for each separated component [1] [5]. This combination effectively addresses the key limitation of chromatography alone, which struggles to identify unknown compounds, and the key limitation of spectroscopy alone, which requires pure analytes for accurate analysis [5] [6].

The Fundamentals of GC-MS

Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) stands as one of the most established and reliable hyphenated techniques, often regarded as a "gold standard" in forensic and analytical chemistry for the definitive identification of substances [3] [4]. Its power derives from the seamless fusion of two powerful techniques: Gas Chromatography (GC), which excels at separating volatile components of a mixture, and Mass Spectrometry (MS), which provides a unique molecular fingerprint for each separated component.

Principles of Gas Chromatography

The gas chromatograph functions as the separation engine of the system. A sample is injected into a heated inlet, where it is instantly vaporized. A steady flow of inert carrier gas (such as helium or hydrogen) transports the vaporized sample through a long, narrow column [5] [4]. Inside this column, which is coated with a thin film of stationary phase, the different components in the sample interact with the coating to varying degrees. These differential interactions cause each compound to travel through the column at a distinct speed, leading to their separation in time [5]. The time taken for a compound to exit the column is its retention time, a characteristic parameter used in qualitative analysis [1].

Principles of Mass Spectrometry

As each separated component elutes from the GC column, it enters the mass spectrometer through a heated transfer line [5]. The core of the MS involves three fundamental processes:

- Ionization: The neutral molecules are ionized, most commonly by Electron Ionization (EI). In EI, a high-energy electron beam (typically 70 eV) bombards the molecules, causing them to lose an electron and form positively charged molecular ions [5] [4].

- Mass Analysis: These molecular ions are often unstable and fragment into smaller, characteristic ions. The resulting cocktail of ions is then separated based on their mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) by a mass analyzer [5]. Several types of analyzers exist, each with its own advantages, as detailed in Table 1.

- Detection: The separated ions are detected, and their abundances are measured. The result is a mass spectrum: a plot of ion abundance versus m/z that serves as a unique fingerprint for the compound [3] [5].

The combination of a compound's GC retention time and its MS fragmentation pattern provides a powerful, two-dimensional identifier that offers a very high level of confidence in confirming the identity of an unknown substance in forensic analysis [5] [4].

GC-MS Workflow

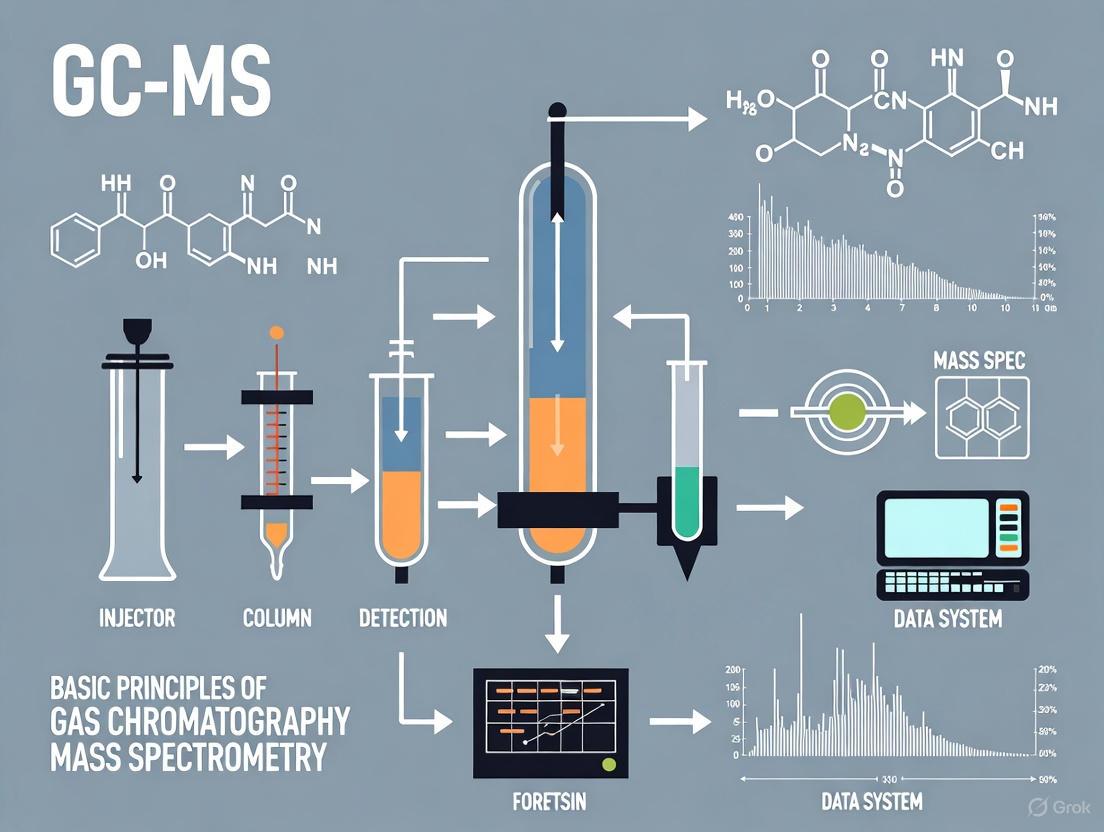

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow of a GC-MS system, from sample injection to data analysis:

GC-MS Instrumentation and Methodologies

A deep understanding of the components and operational parameters of a GC-MS system is crucial for developing robust forensic methods. The instrument is composed of two main building blocks: the gas chromatograph and the mass spectrometer, interfaced to maintain the integrity of the separation and the vacuum of the MS [4].

Key Instrumental Components

- Carrier Gas System: Requires a high-purity, chemically inert gas such as Helium, Hydrogen, or Nitrogen. The gas is regulated by a pressure controller to ensure a constant flow rate through the system, typically in the range of 1-3 mL/min for capillary columns [5] [4].

- Injection Port: The sample is introduced here, often via an auto-sampler. The port is heated to vaporize the liquid sample instantly. For capillary columns, a split/splitless injector is standard, allowing for the injection of very small volumes (e.g., 1 µL) in a split mode to prevent column overload, or in a splitless mode for trace analysis [4].

- GC Column: The heart of the separation. Modern forensic applications primarily use capillary columns (e.g., 10-30 m length, 0.1-0.25 mm internal diameter) which are coated with a thin film of stationary phase. Common stationary phases include 5% phenyl polysiloxane (e.g., HP-5) for a wide range of analytes, and polyethylene glycol (e.g., Carbowax) for more polar compounds [5] [4].

- Ion Source: This is where the neutral molecules are ionized after eluting from the GC column. Electron Ionization (EI) is the most prevalent method in forensic GC-MS because it produces extensive, reproducible fragmentation patterns that can be matched against standard reference libraries [5] [4].

- Mass Analyzer: This component separates the ions based on their m/z. The choice of analyzer depends on the application requirements, such as sensitivity, resolution, and acquisition speed, as detailed in Table 1.

- Detector and Data System: The separated ions are detected, typically by an electron multiplier, generating an electronic signal that is processed by specialized software to produce chromatograms and mass spectra [5].

Table 1: Common Mass Analyzers Used in GC-MS

| Analyzer Type | Mass Resolution | Key Principle | Common Use in Forensics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quadrupole | Unit Mass | Filters ions using DC/RF voltages [5] | Routine targeted screening and quantification; can operate in Full Scan or Selected Ion Monitoring (SIM) mode for higher sensitivity [5]. |

| Ion Trap | Unit Mass | Traps and ejects ions sequentially based on m/z [5] | Structural elucidation through MS/MS experiments, useful for confirming unknowns. |

| Time-of-Flight (ToF) | Unit to High | Measures the time ions take to travel a fixed distance [5] | Untargeted screening and identification of unknowns due to fast acquisition and high mass accuracy. |

Experimental Protocol for Forensic Drug Screening

The following is a detailed methodology for the analysis of a suspected drug sample using GC-MS, incorporating key steps from sample preparation to data interpretation.

Sample Preparation:

- Extraction: Accurately weigh ~10 mg of the homogenized solid sample. Add 10 mL of a suitable organic solvent (e.g., Methanol, Chloroform) and vortex mix for 2 minutes to extract the analytes. For biological fluids like urine or blood, a liquid-liquid or solid-phase extraction (SPE) is required to remove matrix interferences [4].

- Derivatization (if needed): For compounds with polar functional groups (e.g., alcohols, carboxylic acids) that are not amenable to GC, a derivatization step may be necessary. This involves reacting the analyte with a reagent like MSTFA (N-Methyl-N-trimethylsilyltrifluoroacetamide) to produce a more volatile and thermally stable derivative [1].

- Filtration and Dilution: Pass the extract through a 0.45 µm PTFE syringe filter. Dilute the filtrate appropriately with solvent to bring the analyte concentration within the linear dynamic range of the instrument.

Instrumental Conditions:

- GC Column: HP-5ms (30 m length × 0.25 mm ID × 0.25 µm film thickness) or equivalent [4].

- Carrier Gas: Helium, constant flow mode at 1.0 mL/min.

- Inlet Temperature: 250°C, splitless injection mode with a 1 µL injection volume.

- Oven Temperature Program: Initial temperature 70°C (hold 2 min), ramp at 20°C/min to 300°C (hold 5 min). Total run time: 16.5 min.

- MS Conditions: Ionization mode: EI, 70 eV. Ion source temperature: 230°C. Quadrupole temperature: 150°C. Solvent delay: 3 min. Data acquisition: Full scan mode, m/z range 40-550 [5] [4].

Data Analysis and Interpretation:

- Chromatogram Examination: Review the Total Ion Chromatogram (TIC) for the presence and retention times of all peaks.

- Library Searching: For each peak of interest, extract its mass spectrum and perform a library search against a commercial database (e.g., NIST/EPA/NIH Mass Spectral Library). A high similarity index (often >85%) provides preliminary identification [5].

- Confirmation: Confirm the identity by comparing the retention time and mass spectrum of the unknown with those of a certified reference standard analyzed under identical conditions [5] [4].

Applications in Forensic Research and Drug Development

GC-MS has cemented its role as a fundamental tool in forensic science and pharmaceutical research due to its specificity, sensitivity, and robustness. Its applications span from initial drug discovery to the final presentation of evidence in a court of law.

Core Forensic and Pharmaceutical Applications

Table 2: Key Applications of GC-MS in Forensics and Drug Development

| Application Area | Specific Use-Cases | Value Provided by GC-MS |

|---|---|---|

| Forensic Toxicology | Screening and confirmation of drugs of abuse (e.g., cannabinoids, opioids, amphetaines) and their metabolites in biological fluids [3] [4]. | Provides unambiguous identification required for legal proceedings; high sensitivity allows detection of trace levels. |

| Controlled Substance Analysis | Identification of unknown powders, pills, and plant materials; determination of purity and cutting agents [4]. | Considered a "gold standard"; the mass spectrum acts as a definitive fingerprint for the drug molecule itself. |

| Arson and Fire Investigation | Identification of ignitable liquid residues (e.g., gasoline, kerosene) in fire debris [3]. | Can separate and identify complex mixtures of hydrocarbons, providing evidence of accelerant use. |

| Pharmaceutical Development | Analysis of drug metabolism and pharmacokinetics (DMPK); identification of synthetic impurities and degradation products [3]. | Enables tracking of a drug and its metabolites in biological systems, crucial for safety and efficacy studies. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful GC-MS analysis relies on a suite of high-purity reagents and consumables. The following table details key items used in a typical forensic drug analysis protocol.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for GC-MS Analysis

| Item Name | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Solvents (e.g., Methanol, Chloroform) | To dissolve and extract the analyte from the sample matrix without introducing interfering contaminants [4]. |

| Certified Reference Standards | Pure compounds of known identity and concentration used for calibration, method validation, and confirmation of analyte identity via retention time matching [5]. |

| Derivatization Reagents (e.g., MSTFA, BSTFA) | To chemically modify polar, non-volatile analytes into volatile, thermally stable derivatives suitable for GC-MS analysis [1]. |

| Internal Standards (e.g., deuterated analogs of target analytes) | Added in a known amount to the sample; used to correct for variability in sample preparation and instrument response, improving quantitative accuracy [5]. |

| Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) Cartridges | Used for sample clean-up and pre-concentration of analytes from complex matrices like blood or urine, reducing ion suppression and extending column life [1] [2]. |

The advent of hyphenated techniques like GC-MS has fundamentally transformed the landscape of analytical chemistry, particularly in the demanding field of forensic science. By uniting the superior separation power of gas chromatography with the unequivocal identification capabilities of mass spectrometry, this technique provides a comprehensive solution for analyzing complex mixtures. It delivers the high specificity and sensitivity required to meet the rigorous standards of evidence in legal contexts and the stringent demands of drug development pipelines. As these technologies continue to evolve, with advancements in areas like fast GC, high-resolution mass spectrometry, and sophisticated data processing software, their power to separate, identify, and quantify will only grow. This ongoing innovation ensures that GC-MS will remain an indispensable cornerstone of analytical science, enabling researchers and forensic experts to uncover the truth hidden within even the most complex of samples.

Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) combines two powerful analytical techniques to separate, identify, and quantify complex mixtures of chemical compounds. This hyphenated system brings together the exceptional separation power of gas chromatography with the unparalleled identification capabilities of mass spectrometry. In forensic research, this makes GC-MS an indispensable tool for detecting and confirming the presence of specific substances, from drugs and toxins to trace evidence like fiber dyes or ignitable liquids [7]. The instrument works on the fundamental principle of first separating the volatile components of a sample in the GC, then ionizing and fragmenting these molecules in the MS to produce distinctive mass spectra that serve as chemical fingerprints for identification [8] [5]. The following diagram illustrates the complete pathway of an analyte through the GC-MS system, from injection to detection.

The Gas Chromatograph (GC): Separation Module

The gas chromatograph serves as the front-end of the system, responsible for the physical separation of a sample's individual components. This is critical because it ensures that compounds enter the mass spectrometer one at a time, allowing for clean and unambiguous identification [5].

Core Components & Function

- Carrier Gas: An inert gas, such as helium, hydrogen, or nitrogen, which transports the vaporized sample through the system. The carrier gas must be chemically inert to avoid reacting with the sample or the instrument components [9] [10]. The choice of gas involves a trade-off between efficiency, safety, and cost, as summarized in Table 1.

- Inlet / Vaporization Chamber: The sample introduction point. For liquid samples, the inlet is heated to instantly vaporize the sample and mix it with the carrier gas stream [5]. Common types include split/splitless injectors for capillary columns.

- Analytical Column: The heart of the separation. This is a long, thin fused-silica capillary tube (typically 10-30 meters long and 0.1-0.25 mm in internal diameter) coated on the inside with a thin layer of stationary phase [5]. As the vaporized compounds are carried through the column by the carrier gas, they interact with the stationary phase. Differences in these interactions—based on a compound's boiling point and polarity—cause each compound to spend a different amount of time in the column, leading to separation [8]. The time a compound takes to travel through the column to the detector is its retention time, a key identifying characteristic [10].

Table 1: Comparison of Common GC Carrier Gases

| Carrier Gas | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen (H₂) | High diffusivity for good separation efficiency; short analysis time [9] | Flammable; not completely inert and may react with some compounds [9] |

| Helium (He) | Inert, non-flammable, and safe; provides high resolution [9] | Expensive and not always readily available [9] |

| Nitrogen (N₂) | Cheap and easily available [9] | Lower separation resolution; longer analysis time; not ideal for temperature-programmed analysis [9] |

The Mass Spectrometer (MS): Detection and Identification Module

Once separated, the neutral molecules eluting from the GC column are analyzed by the mass spectrometer. The MS acts as a highly informative detector that identifies compounds based on their mass and structure [8].

The Ion Source: Creating Charged Particles

The first component the separated chemicals encounter in the MS is the ion source. Here, neutral molecules are converted into charged ions, making them susceptible to electric and magnetic fields. The most common method is Electron Ionization (EI) [8] [5]. In an EI source, a heated metal filament emits a beam of high-energy electrons (typically 70 eV). When a molecule passes through this beam, it is bombarded, causing it to lose an electron and form a positively charged molecular ion (M⁺•). This molecular ion is often unstable and possesses excess energy, leading it to break apart into smaller, characteristic fragment ions [8] [5]. The pattern of these fragments is highly reproducible and specific to the molecular structure of the compound.

The Mass Analyzer: Sorting Ions by Mass

The fragment and molecular ions are then accelerated into the mass analyzer, which separates them based on their mass-to-charge ratio (m/z). For most ions generated by EI, the charge is +1, so m/z effectively represents the mass of the ion [5]. The most common type of mass analyzer for benchtop GC-MS is the quadrupole [8] [11]. A quadrupole consists of four parallel rods to which a combination of DC and radio frequency (RF) voltages are applied. By rapidly varying these voltages, the quadrupole can act as a mass filter, allowing only ions of a specific m/z to pass through to the detector at any given moment. The instrument rapidly scans across a predetermined mass range, building a mass spectrum for each point in time during the chromatographic run [8].

The Ion Detector: From Ions to Signal

The ions that pass through the mass analyzer strike the detector, typically an electron multiplier. This device amplifies the minute current produced by the arriving ions into a measurable electrical signal [8] [11]. The signal is then sent to a computer system, which processes it to generate the chromatograms and mass spectra used for analysis [5].

Data Analysis: From Raw Signal to Forensic Evidence

GC-MS data is three-dimensional, comprising retention time, signal intensity (abundance), and mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) [5]. This rich dataset can be interrogated in several ways to perform both qualitative and quantitative analysis.

Primary Data Acquisition Modes

- Total Ion Chromatogram (TIC): The TIC is the most fundamental chromatogram. It is constructed by summing the intensities of all ions detected at each point in time during the GC run. It provides a universal detection view, where each peak represents a different compound (or co-eluting compounds) exiting the GC column [11] [5].

- Mass Spectrum: At every second along the TIC, a full mass spectrum can be obtained. This spectrum is a "fingerprint" that plots the intensity of ions versus their m/z. This fingerprint can be searched against extensive commercial spectral libraries for identification [11] [10]. Key features of a mass spectrum include the molecular ion (the heaviest ion, representing the intact molecule) and the base peak (the most intense fragment ion) [11].

Advanced Techniques for Targeted Analysis

For more sensitive or specific analysis, especially in complex matrices common in forensics, other data processing and acquisition modes are employed, as illustrated in the workflow below.

- Extracted Ion Chromatogram (EIC): After a full scan data file is acquired, the data system can extract the signal for a specific ion or set of ions. This is a powerful software-based filtering technique that simplifies the chromatogram, reduces background noise, and helps confirm the identity of a target compound by monitoring its characteristic ions [11].

- Selected Ion Monitoring (SIM): In this acquisition mode, the mass spectrometer is programmed before the analysis to monitor only a few specific ions characteristic of the target analytes. By ignoring all other ions, the instrument can spend more time measuring the signals of interest, resulting in significantly improved sensitivity and lower detection limits for quantitative analysis [11] [5]. This is distinct from EIC, as it is a separate experiment, not a data processing technique [11].

Experimental Protocol: Forensic Fiber Analysis by GC-MS

The following detailed methodology, adapted from a 2025 study, demonstrates the application of GC-MS/MS for the forensic discrimination of polyester fibers based on their dye content [12].

Application: Discrimination of single polyester fibers for forensic comparison. Objective: To identify aromatic amines derived from azo dyes within polyester fibers, providing a chemical signature for sample differentiation.

Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for GC-MS Forensic Fiber Analysis

| Reagent / Material | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Chlorobenzene | Solvent for extraction of disperse azo dyes from the polyester fiber matrix [12]. |

| Sodium Dithionite | Reducing agent that cleaves the azo bonds (-N=N-) in the dyes to yield aromatic amines [12]. |

| Citrate Buffer | Provides a stable pH environment for the controlled reductive cleavage reaction [12]. |

| Chloroform / 1,2-Dichloroethane | Extraction solvents used in Dispersive Liquid-Liquid Microextraction (DLLME) to concentrate the aromatic amines prior to analysis [12]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Sample Preparation: A single polyester fiber (~2 cm in length) is placed into a micro-vial.

- Dye Extraction: Add 100 µL of chlorobenzene to the vial and heat (e.g., 100°C for 10 minutes) to extract the disperse dyes from the fiber.

- Reductive Cleavage:

- Transfer the extract to a vial containing 1 mL of citrate buffer (pH ~6).

- Add 10 µL of a fresh sodium dithionite solution.

- Heat the mixture at 70°C for 30 minutes to reduce the azo dyes into their constituent aromatic amines.

- Analyte Concentration (DLLME):

- After reduction, cool the solution.

- Rapidly inject a mixture of 1 mL of acetonitrile (disperser solvent) and 100 µL of chloroform (extraction solvent) into the sample vial.

- Centrifuge to form a sedimented droplet of the chloroform phase, now enriched with the aromatic amines.

- Collect the droplet for analysis.

- GC-MS/MS Analysis:

- Instrument: GC system hyphenated to a triple quadrupole (tandem) mass spectrometer.

- GC Column: Standard non-polar or mid-polar capillary column (e.g., 5% diphenyl / 95% dimethyl polysiloxane).

- Ionization: Electron Ionization (EI) at 70 eV.

- Data Acquisition: Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM). First, analyze a reference sample in full scan mode to identify target amines and their characteristic precursor ions. Then, for high-sensitivity analysis of evidence samples, use an optimized MRM method that monitors specific precursor ion > product ion transitions for each amine.

- Data Interpretation and Discrimination: Compare the MRM chromatograms of the evidence and reference fibers. The presence or absence of specific aromatic amine signals, identified by their retention times and MRM transitions, is used to differentiate the fiber samples. The high selectivity of MRM minimizes interferences, allowing for robust discrimination even with trace-level analytes [12].

The GC-MS instrument, a synergistic combination of a separation module and an identification module, provides a powerful platform for forensic analysis. Deconstructing its components—from the GC inlet and column to the MS ion source, quadrupole analyzer, and electron multiplier—reveals the sophisticated engineering that enables the detection and definitive identification of chemical substances. The versatility in data acquisition modes, from full scan for unknown identification to SIM and MS/MS for targeted, high-sensitivity quantification, makes it adaptable to a wide range of forensic challenges. As demonstrated in the fiber analysis protocol, the sensitivity and selectivity of modern GC-MS/MS systems allow forensic scientists to extract meaningful chemical data from minute traces of evidence, solidifying its status as a cornerstone technique in forensic chemistry research and casework.

Gas chromatography (GC) is a cornerstone analytical technique in forensic science, providing the critical ability to separate, identify, and quantify volatile components within complex mixtures encountered as evidence [13]. When coupled with mass spectrometry (MS), it forms gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS), a powerful tool that is a primary pillar in analytical chemistry for characterizing chemical substances [14]. In forensic contexts, this capability is essential for analyzing diverse materials such as ignitable liquid residues in fire debris, controlled substances in seized drugs, and other trace evidence, providing scientific data that can determine whether a fire was intentionally set or identify the composition of an unknown powder [15] [13].

The fundamental principle of GC separation lies in the differential partitioning of analytes between a stationary phase and a mobile gas phase [16]. The sample is vaporized and transported by an inert carrier gas through a column containing the stationary phase. Separation occurs because each component interacts differently with the stationary phase; compounds with stronger affinities are retarded, while those with weaker interactions elute more rapidly [13]. This process results in the physical separation of mixture components over time, allowing for their individual detection and measurement [16]. The distribution constant (Kc), which is the ratio of a compound's concentration in the stationary phase to its concentration in the mobile phase, governs this movement and is the chemical parameter that enables chromatographic separation [16].

Core Principles of Chromatographic Separation

The Separation Mechanism

At its core, the gas chromatograph functions as a highly efficient distillation system. Separation hinges on two primary physicochemical properties of the analytes: their relative volatility and their affinity for the stationary phase [13]. As the vaporized sample is carried through the column by the mobile phase (carrier gas), each analyte continually partitions between the two phases. Analytes with higher volatility and lower affinity for the stationary phase spend more time in the mobile gas phase and move through the column more quickly, resulting in shorter retention times. Conversely, analytes with lower volatility and higher stationary phase affinity are delayed, exhibiting longer retention times [16] [13]. This differential migration is the fundamental mechanism that resolves a complex mixture into its individual components as they exit the column.

Key Instrumental Components

A gas chromatograph consists of several integrated subsystems, each critical to achieving a successful separation. The sequence of components and their functions are visualized in the following workflow:

The process begins at the injection port, where a precise amount of sample is introduced, typically via a syringe or autosampler, and instantly vaporized in a heated chamber [13]. The vaporized sample is then mixed with the carrier gas—an inert gas such as helium or nitrogen—which acts as the mobile phase to transport the sample through the system [16] [13]. The heart of the instrument is the column, a long, coiled tube housed within a temperature-controlled oven. The interior of the column is coated with the stationary phase, a material that selectively interacts with the analytes [16] [13]. Modern systems primarily use capillary columns with minimal inner diameters to achieve high separation efficiency. Finally, as separated components exit the column, they enter a detector. In GC-MS, this is a mass spectrometer, which ionizes the molecules, separates the ions by their mass-to-charge ratio, and provides data for both identifying and quantifying each compound [13] [15].

Forensic Applications and Experimental Protocols

Analysis of Ignitable Liquid Residues in Fire Debris

The identification of ignitable liquid residues (ILRs) in fire debris is one of the most prevalent applications of GC-MS in forensic laboratories [15]. Its objective is to determine whether materials recovered from a fire scene contain traces of accelerants like gasoline or diesel fuel, which can indicate arson. The analysis involves a multi-step protocol designed to extract and identify volatile organic compounds from complex, burned substrate matrices.

A detailed methodology for this analysis, adapted from forensic literature, is outlined below [15]:

- Sample Preparation: Simulated fire debris samples are created by spiking a substrate (e.g., wood, carpet) with a neat ignitable liquid (e.g., gasoline, diesel fuel). The substrate is then burned to simulate real fire conditions. For analysis, volatile compounds are extracted from the debris using techniques like passive-headspace extraction, often involving heating the sample in a sealed container to drive volatiles into the headspace, where they are adsorbed onto a carbonaceous strip [15].

- Sample Introduction: The extracted residues are desorbed from the collection strip using a small volume of solvent like dichloromethane. An aliquot of this solution is then introduced into the GC-MS system. Rapid screening methods may use a short (e.g., 2 m) GC column for fast analysis (≈1 minute) [15].

- Chromatographic Separation: The sample is vaporized in the injection port at high temperatures (e.g., 250°C). Separation is achieved using a non-polar or low-polarity column, such as a 100% polydimethylsiloxane (DB-1) column. A common temperature program involves a rapid ramp to separate volatile components efficiently. For rapid GC-MS, the oven may be held isothermal at a high temperature (e.g., 280°C) to prevent recondensation of analytes [15].

- Detection and Identification: Separated components eluting from the column are detected by the mass spectrometer. Data analysis involves examining the total ion chromatogram (TIC) and utilizing extracted ion profiles (EIPs). EIPs are crucial for isolating characteristic ions of target compounds (e.g., alkylbenzenes, polyaromatic hydrocarbons) from complex background interference generated by the burned substrate. Data deconvolution software is often employed to aid in identifying co-eluting peaks [15].

Advanced Visualization: Stained Chromatograms and Substance Maps

Emerging visualization techniques enhance the interpretability of complex forensic data. One advanced method involves "staining" or color-coding gas chromatograms based on mass spectral similarity [14]. In this technique:

- Recorded mass spectra are compared and sorted according to their similarity on a self-organizing map that was pre-trained on a large mass spectral database.

- The location of a mass spectrum on this map is then converted into a specific color using the hue, saturation, and lightness (HSL) color space.

- The resulting color-coded peaks in the chromatogram immediately convey the structural similarity and likely substance class of the detected analytes, facilitating rapid identification and inspection [14].

Furthermore, these data can be converted into substance maps, which are retention-time-independent summaries of the chromatogram. These maps provide an overview of the analytes present in a sample, independent of the specific analytical conditions used for separation. They are particularly useful for directly comparing samples analyzed with different GC setups and for quantifying structurally similar compounds that elute at different times [14].

Quantitative Data and Research Reagents

Performance Data for Forensic GC-MS Analysis

The efficacy of GC-MS methods is quantified through rigorous validation. The table below summarizes key performance characteristics for a rapid GC-MS method developed for ignitable liquid analysis, demonstrating the sensitivity achievable for target compounds [15].

Table: Limits of Detection (LOD) for Compounds in Ignitable Liquids via Rapid GC-MS

| Compound Name | Chemical Category | Limit of Detection (mg/mL) |

|---|---|---|

| p-Xylene | Aromatic | 0.012 |

| n-Nonane | Alkane | 0.018 |

| 1,2,4-Trimethylbenzene | Aromatic | 0.015 |

| n-Decane | Alkane | 0.016 |

| 1,2,4,5-Tetramethylbenzene | Aromatic | 0.014 |

| 2-Methylnaphthalene | Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon | 0.017 |

| n-Tridecane | Alkane | 0.013 |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of forensic GC-MS analysis relies on a suite of specialized reagents and consumables. The following table details key materials and their functions within the analytical workflow.

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for Forensic GC-MS

| Item Name | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| DB-1 / DB-5 MS GC Columns | Non-polar or low-polarity stationary phases (100% polydimethylsiloxane or 5% phenyl-equivalent) standard for separating a wide range of organic compounds encountered in forensic samples like ignitable liquids and drugs [15]. |

| Helium Carrier Gas | An inert, high-purity (99.999%) mobile phase that transports the vaporized sample through the column without reacting with analytes [15]. |

| C7-C30 n-Alkane Standard Solution | A calibrated mixture used for calculating Kovats Retention Indices, which helps identify unknown compounds by normalizing their retention times against a known scale, independent of minor instrumental fluctuations [16]. |

| Dichloromethane (DCM) | A high-purity organic solvent (≥99.9%) used to desorb volatile compounds from collection devices (e.g., carbon strips from passive-headspace extraction) and prepare standard solutions and sample extracts for injection [15]. |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Neat, high-purity analytical standards of specific compounds (e.g., p-xylene, 2-methylnaphthalene) used for method development, calibration, and determining limits of detection [15]. |

| Mass Spectral Libraries (NIST, Wiley) | Extensive databases of known compound mass spectra. Software compares the mass spectrum of an unknown analyte from the GC-MS against these libraries to propose identifications [14]. |

Data Presentation and Accessibility in Forensic Analysis

Graphical Representation of Chromatographic Data

The primary data output from a GC or GC-MS analysis is a chromatogram—a plot of the detector's response as a function of time [17]. Each peak represents a separate analyte, with the retention time serving as a characteristic identifier and the peak area being proportional to the analyte's concentration [13]. For complex forensic samples, additional data visualization tools are essential:

- Extracted Ion Profiles (EIPs): These are chromatograms reconstructed by plotting the abundance of only one or a few selected ions. EIPs are vital for forensic applications like fire debris analysis, as they can reveal the presence of a specific class of compounds (e.g., alkanes, aromatics) that might otherwise be obscured by the complex background in the total ion chromatogram [15].

- Bar Graphs and Pareto Charts: Used in forensic reporting to compare the relative abundance of specific compounds across different samples or to show the frequency of certain evidence types [18].

- Scatter Plots: Employed in chemometrics to visualize the clustering of samples based on their chemical composition, aiding in the classification of unknown liquids or the comparison of evidence samples [17].

Adherence to Accessibility and Contrast Standards

When generating diagrams, charts, and reports for scientific publication and legal proceedings, it is imperative to ensure that all graphical elements are accessible to individuals with color vision deficiencies. This aligns with WCAG (Web Content Accessibility Guidelines) standards, which stipulate minimum contrast ratios [19] [20].

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for analyzing a forensic sample, incorporating high-contrast colors from the specified palette to ensure accessibility:

Key contrast guidelines for scientific diagrams include [19] [20]:

- Normal Text: A minimum contrast ratio of 4.5:1 against the background.

- Large Text (18pt+): A minimum contrast ratio of 3:1 against the background.

- Graphical Objects & UI Components: Any non-text element (e.g., diagram nodes, lines, icons) required to understand the content must have a contrast ratio of at least 3:1 against adjacent colors.

By adhering to these principles, forensic scientists ensure their findings are presented clearly, accurately, and accessibly, which is paramount when presenting complex scientific evidence in a legal context.

Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) is universally recognized as the gold standard in forensic trace evidence analysis due to its unparalleled ability to separate components in complex mixtures and provide definitive identification [21]. This technique combines the superior separation power of gas chromatography (GC) with the identification capabilities of mass spectrometry (MS), creating a powerful tool for analyzing everything from ignitable liquids and drugs to sexual lubricants and automotive paint [21] [10]. In forensic contexts, the mass spectrometer functions as a sophisticated detector that generates unique chemical "fingerprints" from evidence, providing both qualitative identification (what a substance is) and quantitative measurement (how much is present) to support criminal investigations [22].

The fundamental principle of GC-MS analysis involves separating volatile components in a mixture through the gas chromatograph and then detecting them in the mass spectrometer, which identifies and measures the concentration of chemicals based on their mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) [23] [10]. This provides a three-dimensional data set: retention time from the GC, signal intensity, and mass spectral information from the MS, creating a comprehensive profile of the sample's composition [5].

Core Technology: How the Mass Spectrometer Works

The mass spectrometer comprises three essential components that work in sequence to generate forensic fingerprints: the ion source, the mass analyzer, and the detector [24]. These components operate under high vacuum (approximately 10⁻⁵ to 10⁻⁸ torr) to allow ions to travel without interference from air molecules [24].

Ionization: Creating Charged Particles

The first critical step in mass spectrometry is ionization, where neutral molecules eluting from the GC column are converted into ions. The most common ionization technique in GC-MS is electron ionization (EI), where molecules are bombarded with a high-energy stream of electrons (typically 70 electron volts) emitted from a heated filament [23] [5]. This high-energy collision knocks an electron out of the molecule, creating a positively charged molecular ion (M⁺∙), which is a radical cation [25] [24]. The substantial energy transferred during this process often causes the molecular ion to become unstable and fragment into smaller ions and neutral species [5]. This fragmentation follows predictable patterns based on the molecular structure and bond energies, creating a reproducible fingerprint that can be compared across laboratories [11].

Mass Analysis: Separating Ions by m/z

After ionization, the resulting ions are accelerated and directed into the mass analyzer, which separates them based on their mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) [26]. Most ions produced in EI carry a single charge (z=1), so the m/z value is effectively equivalent to the ion's mass [24]. Several types of mass analyzers are used in forensic applications, each with different performance characteristics [26]:

- Quadrupole Analyzers: Utilize four parallel metal rods with variable electromagnetic fields to filter ions; robust and cost-effective with unit mass resolution [26] [5].

- Ion Traps: Capture and store ions in 3D space using electromagnetic fields before sequentially ejecting them to the detector; capable of multiple stages of fragmentation (MSⁿ) for structural elucidation [26].

- Time-of-Flight (ToF) Analyzers: Separate ions by measuring the time they take to travel down a flight tube; higher mass range and faster acquisition rates, suitable for comprehensive two-dimensional GC (GC×GC) applications [5].

- High-Resolution Accurate Mass (HRAM) Analyzers (Orbitrap, Magnetic Sector): Provide exceptional mass accuracy (<5 ppm) and resolution (>100,000), enabling precise determination of elemental composition [26] [5].

Detection and Data Generation

Separated ions strike the detector, typically an electron multiplier, which amplifies the signal and records the intensity for each m/z value [23] [5]. The recorded data forms a mass spectrum—a histogram plotting m/z against relative abundance [27] [24]. The most intense peak in the spectrum is designated the base peak and assigned a relative abundance of 100%, with all other peaks scaled relative to it [25] [24]. Each data point collected across the chromatographic run contains a full mass spectrum, creating a rich, three-dimensional data set (retention time, intensity, and m/z) for forensic interpretation [5].

Forensic Applications: Chemical Fingerprints in Evidence

GC-MS analysis generates distinctive chemical fingerprints from various types of forensic evidence, providing crucial links between crime scenes, victims, and suspects.

Sexual Assault Investigations: Lubricant Analysis

In sexual assault cases where perpetrators use condoms to avoid DNA transfer, the analysis of sexual lubricants becomes critical [21]. A National Institute of Justice study revealed that approximately 30% of sexual assault kits lack probative DNA profiles, making lubricant analysis an essential alternative investigative tool [21]. Natural oil-based lubricants containing ingredients like cocoa butter, shea butter, and vitamin E present highly complex mixtures that challenge conventional GC-MS due to coelution [21]. Comprehensive two-dimensional GC-MS (GC×GC–MS) has demonstrated superior capability in these analyses, resolving over 25 different components in lubricants where traditional GC-MS showed substantial coelution between 7-20 minute retention times [21]. The resulting two-dimensional chromatographic fingerprint reveals both major and minor components, including isoparaffinic compounds and aldehydes that characterize specific lubricant formulations [21].

Automotive Evidence: Paint and Tire Rubber Analysis

Automotive paint represents chemically complex evidence frequently encountered in hit-and-run accidents and vehicle-related crimes [21]. The analysis typically focuses on the clear coat layer, which contains hindered amine light stabilizers and UV absorbers to protect underlying layers [21]. While pyrolysis-GC-MS (py-GC-MS) currently offers the highest discrimination power for automotive paints, coelution of compounds like toluene and 1,2-propandial limits differentiation of similar clear coats [21]. Py-GC×GC–MS successfully overcomes these limitations by separating coeluting compounds such as α-methylstyrene and n-butyl methacrylate, which would be unresolved in traditional GC-MS [21]. Similarly, tire rubber analysis—valuable for reconstructing vehicle trajectories in hit-and-run incidents—benefits from the enhanced separation of GC×GC–MS when analyzing complex mixtures containing over 200 components, including natural/synthetic rubber, oils, plasticizers, antioxidants, and vulcanizing agents [21].

Toxicology and Controlled Substances

Mass spectrometry applications have permeated all fields of toxicology—environmental, clinical, and forensic—for the analysis of drugs, poisons, and their metabolites [26]. GC-MS and LC-MS (liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry) provide the selectivity and sensitivity required to identify and quantify toxic substances in complex biological matrices [26]. In forensic toxicology, these techniques enable the confirmation of suspected poisons and provide prognostic information to guide patient management and legal proceedings [26]. The identification relies on both the retention time matching and the unique mass spectral fingerprint of each compound, with modern instruments capable of detecting compounds at trace levels (parts-per-billion or even parts-per-trillion) in blood, urine, and tissue samples [26].

Experimental Protocols: Forensic Methodologies

Sample Preparation for Forensic Lubricant Analysis

- Sample Collection: Swabs from evidence are collected using clean cotton swabs moistened with hexane.

- Solvent Extraction: Place swabs in glass vials with 2 mL hexane and agitate via vortex mixing for 60 seconds.

- Concentration: Transfer extract to concentrator tube and evaporate under gentle nitrogen stream to approximately 100 µL.

- Instrumental Analysis: Inject 1 µL of concentrated extract into GC-MS system using splitless injection mode at 250°C.

- Chromatographic Conditions:

- Column: 30 m × 0.25 mm ID, 0.25 µm film thickness 5% phenyl polysilphenylene-siloxane

- Oven Program: 50°C (hold 2 min), ramp to 300°C at 10°C/min (hold 10 min)

- Carrier Gas: Helium, constant flow 1.2 mL/min

- Mass Spectrometric Conditions:

- Ionization: Electron Ionization (70 eV)

- Ion Source Temperature: 230°C

- Transfer Line: 280°C

- Data Acquisition: Full scan mode (m/z 40-550) [21]

Pyrolysis-GC×GC–MS for Automotive Paint Clear Coats

- Sample Preparation: Remove ~50 µg sample from clear coat layer using sterile scalpel.

- Pyrolysis Conditions:

- Pyroprobe: CDS Analytical Pyroprobe 4000

- Temperature Program: 50°C for 2 s, ramp to 750°C at 50°C/s, hold for 2 s

- GC×GC Conditions:

- Primary Column: 30 m × 0.25 mm ID, 0.25 µm film thickness non-polar phase

- Secondary Column: 2 m × 0.15 mm ID, 0.25 µm film thickness mid-polarity phase

- Modulator: Differential flow modulation (DFM) with 2.5 s modulation period

- Oven Program: 40°C (hold 2 min), ramp to 300°C at 3°C/min

- Mass Spectrometric Conditions:

- Ionization: Electron Ionization (70 eV)

- Mass Analyzer: Quadrupole or Time-of-Flight

- Acquisition Rate: 100-200 Hz for ToF (essential for GC×GC peak capture)

- Mass Range: m/z 45-600 [21]

Data Interpretation: Reading Chemical Fingerprints

Mass Spectral Interpretation Fundamentals

A mass spectrum presents as a vertical bar graph with m/z on the x-axis and relative abundance on the y-axis [24]. Key features for interpretation include:

- Molecular Ion (M⁺∙): The heaviest ion (under normal conditions) representing the intact molecule with one electron removed; provides molecular weight information [25] [24].

- Base Peak: The most intense peak in the spectrum, assigned 100% relative abundance [25] [24].

- Fragment Ions: Lower mass ions formed by decomposition of the molecular ion; reveal structural information about the original molecule [25] [5].

- Isotope Patterns: Characteristic clusters of peaks caused by naturally occurring heavy isotopes (e.g., ¹³C, ³⁷Cl, ⁸¹Br); provide information about elemental composition [24].

The "nitrogen rule" states that organic compounds containing only carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen have an even-numbered molecular weight, while those with an odd number of nitrogen atoms have an odd-numbered molecular weight [11]. This provides valuable structural information during interpretation.

Data Acquisition Modes in Forensic Analysis

Table 1: GC-MS Data Acquisition Modes for Forensic Analysis

| Acquisition Mode | Principle | Advantages | Forensic Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full Scan | Continuously records all ions across a specified mass range [10] [11] | Identification of unknowns; Library search capability; Wide analytical scope [5] [11] | Drug screening; Arson analysis (ignitable liquids); Explosives residue; Untargeted metabolomics [10] [26] |

| Selected Ion Monitoring (SIM) | Monitors only pre-selected ions characteristic of target compounds [10] [5] | Increased sensitivity (5-10x over full scan); Reduced chemical noise; Improved detection limits [5] [11] | Targeted drug confirmation; Pesticide analysis in food; Trace environmental contaminants; Quantitative analysis [10] [11] |

| Tandem Mass Spectrometry (MS/MS) | Selects precursor ion, fragments it, and monitors product ions [10] [26] | Enhanced selectivity; Reduced matrix interference; Structural elucidation [10] [26] | Complex matrix analysis; Confirmatory testing; Isotope ratio analysis [10] [5] |

Advanced GC×GC–MS Data Analysis

Comprehensive two-dimensional GC (GC×GC–MS) generates structured chromatographic fingerprints where chemically related compounds form ordered patterns in the 2D separation space [21]. For example, in lubricant analysis, isoparaffinic compounds occupy specific regions (lower arc of the chromatographic plane) while aldehydes appear in distinct locations (circled regions), creating characteristic patterns that differentiate similar formulations [21]. This structured separation allows forensic scientists to quickly identify chemical classes and recognize minor components that would be obscured by coelution in conventional GC-MS [21].

Technical Specifications and Performance Metrics

Table 2: Mass Analyzer Performance Characteristics in Forensic Applications

| Mass Analyzer Type | Mass Resolution | Mass Accuracy (ppm) | Forensic Strengths | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quadrupole | Unit mass (~1000) [26] | 100-500 ppm [26] | Robust; Cost-effective; Good sensitivity in SIM mode [26] [5] | Routine drug analysis; Environmental contaminants; Targeted quantitation [10] [26] |

| Ion Trap (QIT) | 1,000-10,000 [26] | >50 ppm [26] | MSⁿ capability; Good full-scan sensitivity; Compact design [26] | Structural elucidation; Fragmentation studies; Volatile organic compounds [26] |

| Time-of-Flight (ToF) | 1,000-40,000 [26] | <5 ppm [26] | Fast acquisition; High mass range; Untargeted analysis capability [5] | Comprehensive screening; GC×GC applications; Metabolomics; Unknown identification [21] [5] |

| Orbitrap | Up to 150,000 [26] | 2-5 ppm [26] | Ultra-high resolution; Accurate mass measurement; Multi-analyte capability [26] | Elemental composition determination; Complex matrix analysis; Research applications [26] |

| Magnetic Sector | Up to 100,000 [26] | <1 ppm [26] | Highest precision; Isotope ratio measurements [5] | Forensic isotope ratio mass spectrometry; Doping control; Regulatory analysis [5] |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Forensic GC-MS Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Chromatographic Solvents (Hexane, Methanol, Dichloromethane) | Sample extraction and preparation [21] | High purity "GC-MS grade" to reduce background interference; Hexane used for lubricant extraction [21] |

| Derivatization Reagents (MSTFA, BSTFA, PFBHA) | Enhance volatility and stability of polar compounds | Used for drugs, metabolites, and explosives residues; Reduces polarity and improves chromatographic behavior |

| Internal Standards (Deuterated analogs: THC-D₃, Cocaine-D₃, PAH-D₁₂) | Quantitation reference and quality control [22] | Correct for variability in extraction and ionization; Must be added before sample preparation [22] |

| Calibration Standards (Certified reference materials) | Instrument calibration and method validation | Traceable to national standards; Multiple concentration levels for calibration curves [22] |

| GC Columns (5% phenyl polysilphenylene-siloxane, polyethylene glycol) | Compound separation [21] [10] | Low-bleed columns recommended; Dimensions: 10-30 m × 0.1-0.25 mm ID × 0.1-0.25 µm film [21] [10] |

| Quality Control Materials (Certified quality control samples) | Method performance verification | Monitor accuracy, precision, and recovery; Essential for forensic defensibility |

Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) combines two powerful analytical techniques to separate, identify, and quantify volatile chemical compounds within a complex mixture. This instrumentation is a cornerstone of modern analytical laboratories, with GC-MS widely regarded as the "gold standard" for confirmatory testing in fields such as forensic toxicology and pharmaceutical quality control due to its high specificity and sensitivity [28]. The technique is particularly valued for its ability to provide both qualitative (identity) and quantitative (amount) information about sample components, even when they are present at trace levels [10].

The process begins with the gas chromatograph (GC), which separates the volatile components of a mixture based on their physicochemical properties. The separated compounds are then introduced into the mass spectrometer (MS), which acts as a detector that identifies and measures them by creating and sorting ions by their mass-to-charge ratios [29]. The data generated from this process provides a multi-dimensional profile of a sample, with retention time from the GC and mass spectral data from the MS serving as the two primary axes for compound identification and characterization. This guide will detail the interpretation of the three fundamental data components: the retention time, the mass spectrum, and the total ion chromatogram.

The Total Ion Chromatogram (TIC) is one of the most fundamental and primary data outputs from a GC-MS analysis in full scan mode. It represents the summed intensity of all mass spectral peaks belonging to the same mass scan, plotted over the entire duration of the analytical run [30] [11]. In essence, the data system constructs the TIC by adding up the signals for all ions reaching the detector at every point in time [11].

The TIC provides a universal detection profile, as every vapor-phase molecule that elutes from the GC column and reaches the mass spectrometer detector contributes to the signal [11]. This makes it an powerful tool for initial sample assessment. However, this universality also presents a challenge: the TIC includes signals from all sources, including background noise, air, water, column bleed, and other contaminants present in the carrier gas or sample matrix [11]. This can sometimes lead to an elevated baseline in the chromatogram.

Key Characteristics of a TIC

- X-Axis (Retention Time): Shows the time (in minutes) from when the sample was injected to when a compound is detected. Each peak corresponds to a separated component (or co-eluting components) reaching the detector [31].

- Y-Axis (Intensity): Represents the total abundance of all ions detected at that point in time. The area under a peak is generally proportional to the quantity of the compound present, though the response can vary between different compound types [31].

- Peak Shape and Quality: A well-functioning GC-MS system will produce sharp, symmetrical peaks. A limited scan rate in full-scan mode can sometimes result in peaks that are not perfectly Gaussian [11]. Peak width is typically very narrow, often around 0.1 minutes in temperature-programmed capillary GC [11].

Table 1: Comparison of Common GC-MS Chromatogram Types

| Chromatogram Type | Description | Primary Use | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Ion Chromatogram (TIC) | Sum of intensities of all ions in each mass scan [30] [11]. | General, untargeted analysis; initial sample overview. | Universal detection; good for discovering unknown components. | Can be noisy; lower sensitivity for specific targets. |

| Extracted Ion Chromatogram (EIC/XIC) | A chromatogram plotted using the signal of only a single, user-specified ion mass (m/z) extracted from the full TIC data [11]. | Confirmatory analysis; reducing background interference for a known compound. | Reduces chemical noise; improves selectivity and confidence in peak identity. | Requires prior knowledge of the target ion; not all compounds are detected. |

| Selected Ion Monitoring (SIM) | A separate experiment where the MS is programmed to detect only a pre-selected set of ions, rather than scanning a full mass range [11]. | Highly sensitive targeted quantitative analysis. | Significantly reduces noise, increasing signal-to-noise ratio and sensitivity. | Not suitable for untargeted discovery; requires precise method development. |

Retention Time: The First Dimension of Separation

Retention time (RT) is a critical parameter in GC-MS, defined as the time taken for a specific analyte to pass from the injector through the column and to reach the detector [31] [32]. It is the primary metric provided by the gas chromatography step and serves as the first key to unlocking a compound's identity.

The fundamental principle governing retention time is the distribution coefficient (K), which is the ratio of a compound's concentration in the stationary phase (the column coating) to its concentration in the mobile phase (the carrier gas) [32]. A compound with a larger distribution coefficient is retained more strongly by the stationary phase and will, therefore, have a longer retention time [32]. While a rough rule of thumb is that compounds with lower boiling points elute faster, the polarity and chemical interactions with the stationary phase are equally, if not more, important.

Factors Influencing Retention Time

Retention time is not an absolute physical constant and depends on many operational and instrumental factors [32]. When comparing data, it is critical that the analyses are performed under identical conditions.

Table 2: Key Factors Affecting GC-MS Retention Time

| Factor Category | Specific Examples | Impact on Retention Time |

|---|---|---|

| Analysis Conditions | Carrier gas flow rate, oven temperature program (rate, hold times), injection port temperature [31]. | Higher flows and temperatures generally decrease retention times. |

| Column Parameters | Column type (stationary phase chemistry), column dimensions (length, diameter, film thickness), column degradation over time [32]. | A longer column or a thicker film increases retention times. Cutting a column shortens RT [32]. |

| System Condition | Presence of active sites due to contamination, degradation of the column stationary phase (column bleed) [32]. | Can cause peak tailing, adsorption, or shifts in retention time. |

Qualitative Analysis Using Retention Parameters

For qualitative identification, the retention time of an unknown compound's peak is compared to the retention time of a known standard analyzed under the exact same GC-MS conditions [32]. A match in retention time provides supporting evidence for the compound's identity.

Because absolute retention times can be unstable, analysts often use more robust relative parameters:

- Relative Retention: The ratio of the adjusted retention time of the target compound to the adjusted retention time of a reference standard. This cancels out some effects of parameters like column length and carrier gas flow [32].

- Retention Index (RI) / Linear Retention Index (LRI): A system where the retention of an unknown compound is expressed relative to a homologous series of n-alkanes analyzed under the same conditions. LRI is particularly useful because it is simple to calculate from a temperature-programmed analysis and does not require estimating the gas hold-up time [32]. Using LRI improves the accuracy of library searches and facilitates method transfer.

The Mass Spectrum: The Second Dimension of Identification

While the GC provides retention time, the mass spectrometer adds the powerful second dimension of mass information [29]. A mass spectrum is a plot of the intensity of ion signals (relative abundance) versus their mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) [11]. It acts as a unique molecular "fingerprint" that is used for definitive identification.

The process of creating a mass spectrum begins in the ion source. A common method is electron ionization (EI), where vaporized molecules eluting from the GC column are bombarded with a stream of electrons. This high-energy collision causes the neutral molecules to lose an electron and form positively charged molecular ions, which often have excess energy and fragment into smaller, characteristic ions [29]. The resulting pattern of fragments is highly specific to the structure of the original molecule.

Key Features of a Mass Spectrum

- Molecular Ion (M⁺⁺): The ion representing the intact molecule after the loss of a single electron (M⁺⁺). It typically appears at the highest m/z value in the spectrum and its mass indicates the molecular weight of the compound [11] [33]. The "nitrogen rule" states that organic compounds with an even-numbered molecular mass contain zero or an even number of nitrogen atoms, while those with an odd-numbered mass contain an odd number of nitrogen atoms [11].

- Base Peak: The most intense peak in the mass spectrum. Its abundance is set to 100% relative abundance, and all other peaks are scaled relative to it. The base peak represents the most stable or readily formed fragment ion [11] [33].

- Fragment Ions: Peaks resulting from the breakage of chemical bonds in the molecular ion. The pattern of these fragments reveals structural information about the molecule, such as the presence of specific functional groups or side chains [29] [33].

- Isotope Peaks: Most elements have naturally occurring isotopes (e.g., ¹³C, ²H). This results in small M+1, M+2, etc., peaks accompanying the main fragment peaks. The pattern and abundance of these isotope clusters can be used to deduce the elemental composition of the fragment [11].

Diagram 1: The journey of a molecule through the mass spectrometer to generate a mass spectrum.

Integrated Data Interpretation in a Forensic Context

In forensic research, the conclusive identification of a substance is paramount. GC-MS achieves this by combining the evidence from retention time and the mass spectrum. A compound is positively identified when its identity is confirmed by both retention time matching with a known standard and mass spectral matching via library search and interpretation [11].

Experimental Protocol for Confirmatory Drug Analysis

The following detailed methodology outlines a standard protocol for the confirmatory identification of an unknown compound in a forensic drug sample.

1. Sample Preparation:

- The suspected drug sample (e.g., a powder, pill, or biological extract) is dissolved in a suitable volatile solvent such as methanol or acetonitrile.

- For complex matrices like urine or blood, additional steps like liquid-liquid extraction or solid-phase extraction are required to isolate the target analytes and remove interfering compounds [28] [10].

- A known concentration of an internal standard (a compound not expected to be in the sample) is often added to correct for variations in injection volume and instrument response.

2. Instrumental Analysis:

- GC Conditions: A small volume (e.g., 1 µL) of the prepared sample is injected into the GC inlet, which is heated (200-300°C) to instantly vaporize the sample [32]. The vapor is carried by an inert gas (e.g., Helium or Hydrogen) through a capillary column. A standard initial oven temperature program might be: hold at 60°C for 1 minute, ramp at 20°C/min to 300°C, then hold for 5 minutes. The specific column (e.g., 30m x 0.25mm, 0.25µm film, 5% phenyl polysiloxane stationary phase) is selected for its ability to separate compounds of interest.

- MS Conditions: The MS is operated in full scan mode (e.g., m/z 40-500) to collect a complete mass spectrum for every eluting compound. The ion source (EI) is typically set to 70 eV, a standard energy that produces reproducible fragmentation patterns [29]. The transfer line temperature is maintained to prevent condensation of the analytes.

3. Data Analysis and Interpretation:

- The TIC is first examined to locate all eluting peaks.

- The retention time of the unknown peak of interest is compared to the retention time of a certified reference standard of the suspected drug (e.g., cocaine), analyzed using the identical method.

- The mass spectrum at the apex of the unknown peak is extracted. This spectrum is then searched against a commercial mass spectral library (e.g., NIST/EPA/NIH Mass Spectral Library). A high similarity match (e.g., >90% with a clean background) provides strong evidence for the identity of the unknown.

- For absolute confirmation, the sample is re-analyzed using a targeted method like Selected Ion Monitoring (SIM). The MS is programmed to monitor 3-4 characteristic ions (e.g., the base peak and two other significant fragments) from the known mass spectrum of the target drug at its specific retention time. The presence of all diagnostic ions with the correct abundance ratios confirms the identity [11].

Diagram 2: A forensic workflow for the confirmatory identification of an unknown compound using GC-MS.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key consumables and reagents essential for conducting reliable GC-MS analysis in a research or forensic setting.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for GC-MS Analysis

| Item | Function / Purpose | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Standards | Pure compounds of known identity and concentration used for calibration, retention time matching, and mass spectral verification. | Essential for positive identification and accurate quantification. Must be traceable to a certified source. |

| Internal Standards (IS) | A compound(s) added to all samples, calibrators, and quality controls in a known amount. | Corrects for instrument variability and sample preparation losses. Should be structurally similar but chromatographically distinct from the analytes. |

| GC-MS Grade Solvents | High-purity solvents (e.g., methanol, acetonitrile, hexane) for sample preparation and dilution. | Minimal background interference (low MS signal) prevents contamination and artifact peaks. |

| Derivatization Reagents | Chemicals (e.g., MSTFA, BSTFA) that modify polar functional groups (-OH, -NH₂, -COOH) in a sample. | Increases volatility and thermal stability of analytes, improving chromatography and detection sensitivity. |

| Inert Carrier Gases | High-purity gases (e.g., Helium, Hydrogen) used as the mobile phase to carry the sample through the GC column. | Purity (≥99.999%) is critical to prevent oxygen and moisture from degrading the column and causing baseline noise. |

| Capillary GC Columns | Fused silica tubes coated with a thin layer of stationary phase where chemical separation occurs. | Selection (phase chemistry, dimensions) is critical for resolving the target analytes from each other and from matrix interferences. |

The power of GC-MS in forensic research lies in its orthogonal approach to identification. Retention time offers a physicochemical identifier based on a compound's interaction with the chromatographic system, while the mass spectrum provides a structural fingerprint based on its fragmentation pattern. The Total Ion Chromatogram serves as the comprehensive map from which this information is extracted. By rigorously applying the principles of interpreting these three data dimensions—ensuring retention time matches with certified standards, confirming mass spectral fits with library databases, and utilizing diagnostic ion ratios—researchers and forensic scientists can achieve the high level of certainty required for definitive reporting. This multi-parameter confirmation is precisely why GC-MS remains the undisputed gold standard for confirmatory analysis in laboratories worldwide.

Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) combines the separation power of gas chromatography with the identification capabilities of mass spectrometry, creating one of the most powerful analytical tools in forensic science. This technique provides a definitive method for separating complex mixtures and positively identifying individual components through their unique mass fragmentation patterns. Since its commercialization in the late 1960s, GC-MS has become established as a gold standard in forensic laboratories worldwide, providing exceptionally reliable evidence for court proceedings [34] [35]. The technique's unparalleled specificity comes from its dual separation and identification mechanism—compounds are first separated by their physicochemical interactions in the GC column, then ionized and fragmented in the mass spectrometer, generating characteristic spectra that serve as molecular fingerprints [36] [34].

The fundamental strength of GC-MS lies in its ability to provide a 100% specific test that can positively confirm the presence of a particular substance, unlike nonspecific tests that merely indicate the presence of any of several substances in a category [34]. This specificity is crucial in forensic contexts where evidentiary reliability can determine legal outcomes. As Glen P. Jackson, a Distinguished Professor of Forensic and Investigative Science, notes, GC-MS remains "by far the most trusted and commonly used instrumental method of analysis for seized drugs and ignitable liquid residues" in forensic laboratories today [35]. The technique's applications span an enormous range of evidence types, from drugs and toxicological specimens to trace evidence from crime scenes and arson investigations.

Key Evidence Types Analyzed by GC-MS

Forensic laboratories routinely employ GC-MS to analyze diverse evidence types, each presenting unique analytical challenges and requirements. The following table summarizes the primary categories of evidence examined using this technique:

Table 1: Key Evidence Types Analyzed by GC-MS in Forensic Investigations

| Evidence Category | Specific Types of Evidence | Common Analytes Detected | Forensic Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drugs & Toxicology | Seized drugs, blood, urine, oral fluid, hair, tissues | Opioids, stimulants, cannabinoids, benzodiazepines, novel psychoactive substances | Determines intoxication, cause of death, drug possession, compliance monitoring |

| Arson & Fire Debris | Fire debris, accelerant residues, burned materials | Gasoline, kerosene, diesel, turpentine, other ignitable liquids | Establishes arson through accelerant identification, determines fire cause |

| Trace & Biological Evidence | Fibers, paints, polymers, fingerprints, adhesives | Synthetic polymers, dyes, plasticizers, lipid fractions, additives | Links suspects to crime scenes, authenticates materials, provides investigative leads |

| Explosives & Firearms | Explosive residues, propellants, post-blast debris | Nitroglycerin, TNT, RDX, PETN, organic gunshot residues | Identifies explosive materials, links suspects to bomb-making or shooting incidents |

| Environmental & Miscellaneous | Soil, water, air samples, food contaminants, unknown substances | Pesticides, PCBs, volatile organic compounds (VOCs), persistent organic pollutants | Identifies environmental pollutants, determines contamination sources |

Drugs and Toxicological Substances

Drug analysis represents the most frequent application of GC-MS in forensic laboratories [37]. The technique provides unambiguous identification of controlled substances in both seized drug materials and biological specimens. Recent research demonstrates its continued evolution, with methods becoming faster and more sensitive. For instance, a 2025 study developed a rapid GC-MS method that reduced analysis time from 30 to 10 minutes while maintaining excellent sensitivity for substances including cocaine, heroin, synthetic cannabinoids, and pharmaceuticals [38]. This acceleration addresses critical backlog issues in forensic laboratories while delivering reproducible results with relative standard deviations (RSDs) less than 0.25% for stable compounds [38].

In toxicological analysis, GC-MS enables the detection and quantification of drugs and their metabolites in biological matrices at trace concentrations. A novel GC-MS/MS method published in 2025 achieved remarkable sensitivity for opioids and fentanyl analogues in oral fluid, with limits of detection (LODs) ranging from 0.10 to 0.20 ng/mL [39]. This exceptional sensitivity allows forensic toxicologists to identify recent drug use from minimal sample volumes, making the technique invaluable for driving under the influence investigations and postmortem toxicology.

Arson and Fire Debris Evidence

GC-MS plays a critical role in arson investigations by identifying ignitable liquid residues (ILRs) in fire debris. The technique can detect characteristic patterns of hydrocarbons and other compounds that indicate the presence of accelerants such as gasoline, kerosene, or diesel fuel, even after extensive burning [40] [35]. The analysis involves careful sample collection from fire scenes, followed by extraction of volatile compounds using techniques like headspace concentration or purge-and-trap methods, which introduce samples into the GC-MS system [34].

The evidentiary value lies in distinguishing petroleum-based accelerants from pyrolysis products generated by burning building materials, furnishings, and other substrates. GC-MS can separate and identify complex mixtures of aromatic compounds, alkanes, and other markers specific to different classes of ignitable liquids, providing scientific evidence of arson that is routinely admitted in court proceedings [35].

Trace and Biological Evidence

The application of GC-MS to trace evidence has expanded significantly with technological advancements. Comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography coupled with time-of-flight mass spectrometry (GC×GC–TOF-MS) provides unprecedented resolution for complex mixtures encountered in trace evidence [41]. For example, research by Vozka and colleagues employs this approach to analyze the chemical aging of latent fingerprints, monitoring time-dependent changes in lipid composition and oxidative degradation products that can help estimate when fingerprints were deposited [41].

Similarly, GC×GC–TOF-MS is being used to profile volatile organic compounds (VOCs) released during human decomposition, creating a chemical timeline that can assist in determining time since death and improving the effectiveness of human remains detection canines [41]. In polymer analysis, GC-MS identifies specific additives, plasticizers, and stabilizers that can link materials recovered from suspects to those at crime scenes [35].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard Workflow for GC-MS Analysis

The forensic application of GC-MS follows a systematic workflow encompassing sample collection, preparation, instrumental analysis, and data interpretation. The fundamental steps are visualized in the following diagram:

Diagram 1: GC-MS Forensic Analysis Workflow

Sample Preparation Techniques

Proper sample preparation is critical for successful GC-MS analysis in forensic applications. The choice of technique depends on the sample matrix and target analytes:

Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE): Widely used for biological fluids like urine, blood, and oral fluid. SPE cartridges with various stationary phases (C18, mixed-mode, ion-exchange) selectively retain analytes of interest while removing interfering matrix components [39] [42]. For example, a 2025 method for opioids and fentanoids in oral fluid employed SPE with recovery rates consistently exceeding 57% [39].

Liquid-Liquid Extraction (LLE): Commonly applied to seized drugs and solid samples. In the rapid GC-MS method for seized drugs, solid samples were ground and extracted with methanol using sonication, while trace samples were collected with methanol-moistened swabs followed by vortexing [38].

Headspace Sampling: Particularly valuable for volatile compounds in arson evidence and toxicological alcohols. The sample is heated in a sealed vial, and the vapor phase is injected into the GC-MS [42].

Solid-Phase Microextraction (SPME): A solvent-free technique where a coated fiber absorbs analytes from the sample headspace or liquid, then desorbs them directly in the GC injector [42].