Field-Portable Spectroscopy for Explosives Analysis: Techniques, Applications, and Future Directions

This article provides a comprehensive review of portable spectroscopy techniques for the on-scene analysis of explosive materials.

Field-Portable Spectroscopy for Explosives Analysis: Techniques, Applications, and Future Directions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive review of portable spectroscopy techniques for the on-scene analysis of explosive materials. Tailored for researchers and forensic professionals, it covers the foundational principles of techniques like Raman, IR, and NIR spectroscopy, detailing their specific applications in detecting military-grade and homemade explosives (HMEs). The scope extends to methodological workflows, troubleshooting common field challenges such as fluorescence and sample heating, and a critical comparison of instrument performance and validation protocols. By synthesizing the latest research, this review serves as a vital resource for informed technology selection and implementation in field-based security and forensic operations.

The Critical Role and Core Principles of Field-Portable Spectroscopy in Explosives Detection

The threat landscape for explosives has evolved significantly, with homemade explosives (HMEs) becoming increasingly prevalent in improvised explosive devices (IEDs). The past five years have seen almost four thousand explosion incidents in the United States alone, with bomb threats increasing by 230% in 2022 [1]. This escalating threat demands advanced analytical solutions, particularly portable spectroscopy techniques that enable rapid, on-site identification of explosive materials. The proliferation of HMEs presents unique forensic challenges due to their diverse chemical compositions, accessibility of precursor materials, and adaptability of formulations [2]. This application note provides a comprehensive framework for the field analysis of intact explosives and HME precursors using portable spectroscopic techniques, with detailed protocols for researchers and security professionals operating in field environments.

Current Threat Landscape and Analytical Challenges

HMEs have become attractive options for malicious actors due to the commercial availability of precursor materials. Ammonium nitrate (AN) can be readily mixed with various fuels to create ammonium nitrate fuel oil (ANFO), with optimized formulations typically containing 94% ammonium nitrate by weight in 6% fuel oil [1]. Similarly, smokeless powder—categorized as single-base (containing nitrocellulose) or double-base (containing both nitrocellulose and nitroglycerine)—is easily acquired from hardware and outdoor stores for repurposing as HMEs [1].

The detection and identification of explosive compounds require multiple instrumental techniques due to their varied chemical and physical properties. Traditional laboratory-based analysis creates operational delays, as evidence transport and processing can take weeks to months [1]. Field-portable instruments enable law enforcement personnel to collect measurements in real-time, providing immediate reaction capabilities for scene safety and investigation continuation [1]. While these field analyses cannot serve as confirmatory tests for United States courts, they provide critical intelligence for rapid threat assessment.

Portable Spectroscopy Techniques for Explosives Detection

Handheld Raman Spectrometers

Raman spectroscopy is particularly advantageous for explosives detection as a non-destructive technique that allows analysis through containers, greatly reducing interaction between operators and potential explosive compounds [1]. Recent evaluations of handheld Raman spectrometers have demonstrated their capabilities and limitations for detecting intact explosives and HME components.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Handheld Raman Spectrometers

| Spectrometer Model | Laser Wavelength | Key Advantages | Limitations | Detectable Explosives |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rigaku ResQ-CQL | 1064 nm | Higher laser power, better resolution, lower fluorescence, faster analysis | Higher cost | AN, TNT, nitromethane, DPA, EC, MC |

| HandyRam | 785 nm | Lower cost | Higher background fluorescence, lower signal intensity, requires baseline correction | AN, TNT, nitromethane (with reduced sensitivity) |

The 1064 nm laser wavelength in the Rigaku ResQ-CQL provides superior performance due to reduced fluorescence interference compared to 785 nm systems [1]. Sensitivity testing has established limits of detection (LOD) for common explosive materials, with the ResQ-CQL demonstrating enhanced performance across all tested compounds.

Table 2: Sensitivity Data for Explosive Compounds Using Handheld Raman

| Compound | Application | Approximate LOD (Rigaku ResQ-CQL) | Container Interference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diphenylamine (DPA) | Smokeless powder stabilizer | ~10.87 mM in acetone | Minimal from glass/plastic |

| Ethyl Centralite (EC) | Smokeless powder stabilizer | Comparable to DPA | Minimal from glass/plastic |

| Methyl Centralite (MC) | Smokeless powder stabilizer | Comparable to DPA | Minimal from glass/plastic |

| Ammonium Nitrate (AN) | HME precursor | Varies with concentration | Minimal from glass/plastic |

| Trinitrotoluene (TNT) | Military explosive | Varies with concentration | Minimal from glass/plastic |

Complementary Analytical Techniques

While Raman spectroscopy provides valuable capabilities, a multi-technique approach significantly enhances detection reliability. Current market analysis of approximately 80 commercially available mobile explosive detectors reveals wide technological diversity [3]:

Table 3: Portable Detection Technologies for Explosives

| Technique | Example Devices | Sensitivity Range | Key Advantages | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ion Mobility Spectrometry (IMS) | M-ION (Inward Detection) | ppt to ppb range | High sensitivity, fast analysis | Trace detection, checkpoint screening |

| Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) | Griffin G510 (Teledyne FLIR) | ppb range | Confirmatory analysis, high specificity | Forensic identification, evidence processing |

| Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy | Various portable systems | Varies with implementation | Molecular fingerprinting | Chemical identification |

| Laser-Induced Fluorescence (LIF) | Fido X4 (Teledyne FLIR) | Nanogram level | Ultra-trace detection | Vapor detection |

| Quartz Crystal Microbalance (QCM) | EXPLOSCAN (MS Technologies) | ppb range | Low power consumption | Vapor sensing |

Only a few commercially available devices employ two orthogonal analytical techniques, despite the demonstrated advantage of this approach in reducing false alarms and improving detection reliability [3].

Experimental Protocols for Field Analysis of Explosives

Handheld Raman Spectroscopy for Intact Explosives

Principle: Raman spectroscopy measures the inelastic scattering of monochromatic light, providing molecular fingerprint information through vibrational spectroscopy [1].

Materials and Equipment:

- Handheld Raman spectrometer (e.g., Rigaku ResQ-CQL or equivalent)

- Sealed containers with suspected explosive materials

- Personal protective equipment (PPE)

- Standard reference materials for validation (where available)

Procedure:

- Scene Safety Assessment: Establish safety perimeter and don appropriate PPE before approaching suspected materials.

- Instrument Preparation: Power on the handheld Raman spectrometer and allow it to complete self-diagnostic checks. Verify successful performance validation using integrated standards.

- Sample Positioning: Position the spectrometer probe head in direct contact with or close proximity to the container holding the suspected material. Maintain consistent pressure and distance.

- Spectral Acquisition:

- Select appropriate laser wavelength (1064 nm preferred for reduced fluorescence)

- Set integration time to 1-10 seconds based on signal intensity

- Acquire multiple spectra from different sample positions for heterogeneous materials

- For each measurement, collect both raw and processed spectra when available

- Data Analysis:

- Compare acquired spectra against embedded spectral libraries

- Note characteristic peaks for common explosives:

- AN: ~1043 cm⁻¹ (NO₃⁻ symmetric stretch)

- TNT: ~1360 cm⁻¹ (NO₂ symmetric stretch)

- DPA: ~1000 cm⁻¹, ~1300 cm⁻¹ (ring breathing modes)

- Apply baseline correction if significant fluorescence is observed

- Interpretation and Reporting: Document all spectral matches with confidence metrics. Note any container interference observed in the spectra.

Limitations: Raman spectroscopy may exhibit reduced sensitivity for highly fluorescent compounds or low-concentration analytes. Dark-colored materials may absorb laser energy, potentially causing heating effects [1].

Portable GC-MS for Explosive Residue Analysis

Principle: Gas chromatography separates complex mixtures, while mass spectrometry provides definitive identification through molecular fragmentation patterns [4].

Materials and Equipment:

- Portable GC-MS system (e.g., Smiths Detection Guardion or equivalent)

- Solid-phase microextraction (SPME) fibers (PDMS/DVB coating recommended)

- Helium carrier gas cartridge

- Headspace vials

- Microsyringe for direct deposition

- Solvents (acetonitrile, methanol)

Procedure:

- Sample Collection:

- Headspace Sampling: Transfer 100-500 mg of solid sample to headspace vial. Seal and incubate at 22°C for ≥2 hours. Expose SPME fiber to headspace for 10-40 minutes [4].

- Direct Deposition: Dissolve 100-500 mg sample in 10 mL acetone. Deposit 10 μL aliquot onto SPME fiber using microsyringe. Air dry for ≤5 minutes to evaporate solvent [4].

- Instrument Preparation:

- Power on portable GC-MS system and perform manufacturer-specified performance validation

- Verify GC column integrity and MS calibration using test mixture

- Confirm helium pressure and flow rates within specified ranges

- Sample Introduction: Inject SPME fiber into GC inlet for thermal desorption (typically 250-300°C).

- Chromatographic Separation:

- Use 5m MXT-5 capillary column or equivalent

- Program temperature ramp: 40°C (hold 0.5 min) to 300°C at 30°C/min

- Total run time: approximately 3 minutes

- Mass Spectrometric Detection:

- Set ion trap mass spectrometer to electron ionization mode

- Scan range: m/z 35-450

- Compare resulting spectra against NIST database and explosive-specific libraries

- Data Interpretation: Identify explosive compounds based on retention time and mass spectral matching. Common explosive indicators include:

- TNT: m/z 210, 180, 89

- RDX: m/z 128, 120, 103

- PETN: m/z 46, 30, 76

Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) with AI Integration

Principle: SERS enhances Raman signals through plasmonic amplification on nanostructured metallic surfaces, while artificial intelligence improves pattern recognition in complex mixtures [5].

Materials and Equipment:

- Portable Raman spectrometer with SERS capability

- SERS substrates (silver nanoparticles synthesized with sodium borohydride)

- Calcium ions for nanoparticle aggregation and "hotspot" formation

- Sample concentration and purification materials

Procedure:

- Substrate Preparation: Synthesize silver nanoparticles using sodium borohydride as both reducer and activator. Induce controlled aggregation with calcium ions to create signal-enhancing "hotspots" [5].

- Sample Preparation: Apply liquid samples directly to SERS substrate. For solid samples, perform solvent extraction followed by deposition.

- Spectral Acquisition: Collect multiple SERS spectra from different regions of the substrate to account for heterogeneity.

- AI-Enhanced Analysis:

- Process spectral data through deep learning algorithms (K-BPNN model recommended)

- Employ t-SNE for dimensionality reduction in complex spectral datasets

- Compare against established SERS spectral databases for explosive identification

- Validation: Confirm detection limits through calibration curves. Reported systems achieve detection as low as 100 femtograms per milliliter [5].

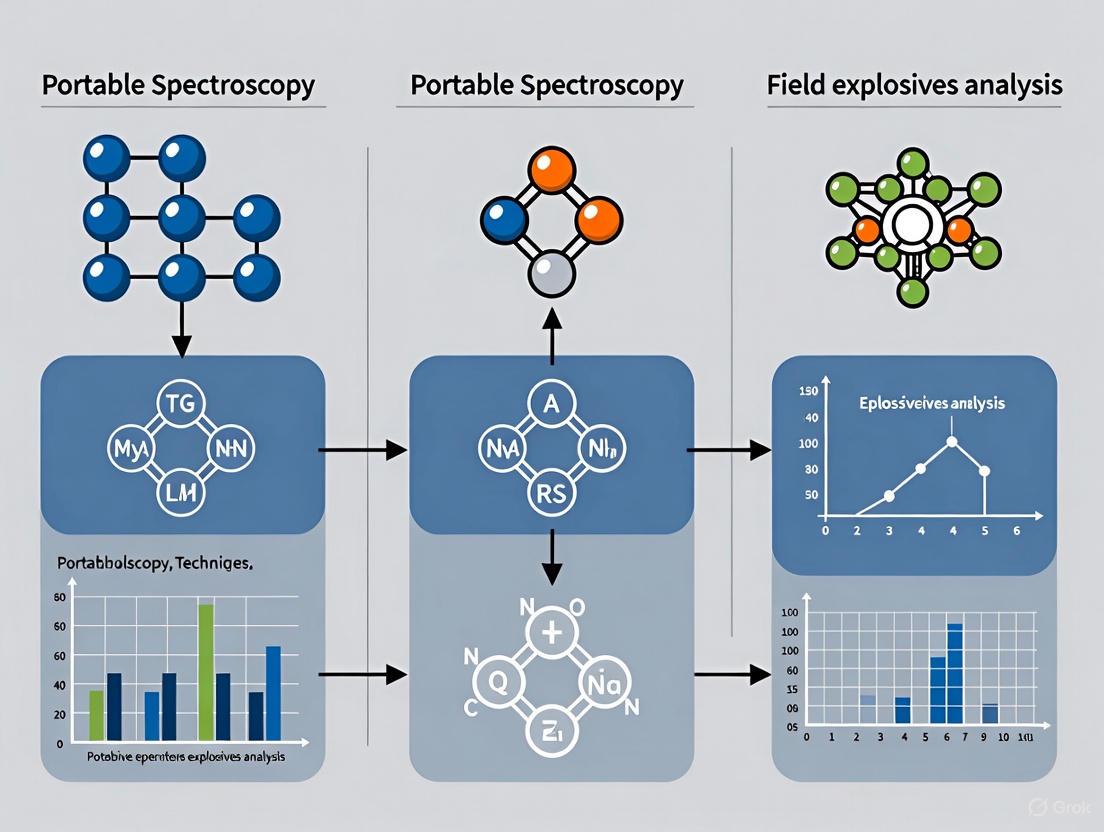

Visualization of Analytical Workflows

Field Deployment Workflow for Explosive Identification

SERS with AI Enhancement Methodology

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Explosives Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples | Handling Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Silver nanoparticles | SERS substrate | Signal enhancement for trace detection | Synthesized with NaBH₄, aggregate with Ca²⁺ [5] |

| PDMS/DVB SPME fibers | Sample preconcentration | Headspace sampling for GC-MS analysis | Thermal desorption at 250-300°C [4] |

| Acetone | Solvent for direct deposition | Dissolving explosive residues for SPME | Allow 5-minute evaporation after deposition [4] |

| Acetonitrile | HPLC/Spectroscopy solvent | Standard preparation for explosive compounds | Use in well-ventilated areas [1] |

| EuMOF/CDs nanocomposites | Ratiometric fluorescence sensing | DPA detection in microfluidic systems | Store in dark, stable at room temperature [6] |

| TMB/H₂O₂ | Chromogenic substrate | Colorimetric detection in microfluidics | Fresh preparation required for each use [6] |

| Ammonium nitrate | Standard for calibration | Reference material for HME detection | Hygroscopic, requires dry storage [1] |

| Diphenylamine (DPA) | Analytical standard | Smokeless powder marker compound | Light-sensitive, use amber vials [1] |

Operational Considerations and Future Directions

The evolving threat of HMEs demands continuous advancement in detection technologies. Future developments should focus on multi-technique integration to overcome the limitations of individual methods. Only a few current commercial devices employ orthogonal techniques, despite the demonstrated benefits for reducing false positives and enhancing detection reliability [3].

Emerging trends include the integration of artificial intelligence with spectroscopic methods, enabling rapid identification of complex mixtures with accuracy rates exceeding 98% [5]. Additionally, smartphone-based sensing platforms show promise for democratizing access to analytical capabilities, though these require further development for explosive detection applications [7].

Microfluidic systems integrated with portable detection technologies offer advantages in reagent consumption, analysis speed, and operational simplicity [6]. These systems are particularly valuable for field deployment where resources are limited and rapid results are essential.

As terrorist groups continue to innovate in bomb-making techniques and exploit security vulnerabilities globally [8], the development and deployment of advanced portable spectroscopy systems remains an operational imperative for public safety and national security.

Portable spectrometers are compact, field-deployable instruments that perform molecular analysis of samples outside traditional laboratory settings. These devices enable on-the-go analysis for field research, raw material identification, and forensic analysis, offering capabilities that were once restricted to benchtop models [9]. The core value of portable spectrometry lies in its ability to provide rapid, in-situ analysis, which is particularly critical in time-sensitive and high-stakes fields like explosives detection and security. By bringing the laboratory to the sample, these instruments eliminate the delays and potential sample degradation associated with transport to a fixed facility, enabling immediate reaction for scene safety and investigation continuity [1].

Within the specific context of explosives analysis, portable spectrometers address unique challenges posed by sensitive and hazardous samples. Their non-destructive nature allows analysis through containers, dramatically reducing investigator interaction with potentially unstable explosive compounds [1]. This technical note details the operational principles, capabilities, and standardized protocols for employing portable spectrometers in field-based explosives research.

Technical Specifications and Comparative Analysis

Commercially Available Portable Spectrometers

Portable spectrometers are characterized by their compact form factors, battery operation, and ruggedized designs capable of withstanding field conditions. The following table summarizes key specifications of selected handheld spectrometers relevant to analytical research.

Table 1: Specifications of Selected Handheld Raman Spectrometers

| Manufacturer | Model/Series | Spectral Range | Resolution | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agilent Technologies | Vaya Raman RM | 350 – 2000 cm⁻¹ | 12 – 20 cm⁻¹ | Biopharma raw materials, small molecule pharmaceuticals [9] |

| Bruker Optics | BRAVO | 300 – 3200 cm⁻¹ | Inquire | Pharma, narcotics, art & restoration, lab/R&D [9] |

| Metrohm USA | Mira | 400 – 2300 cm⁻¹ | 8 – 10 cm⁻¹ | Rapid onsite detection of contaminants in food matrices [9] |

| Rigaku Corporation | ResQ-CQL | 200 – 2500 cm⁻¹ | ~6 – 13 cm⁻¹ | Common threat identification, narcotics, explosives, chemical warfare agents [9] [1] |

Performance Characteristics for Explosives Detection

Evaluation studies provide quantitative performance data critical for method development. Research on detecting intact explosives has demonstrated that spectra for analytes like TNT, nitromethane (NM), and ammonium nitrate (AN) show good reproducibility in both peak location and intensity across instruments [1]. Key findings include:

- Sensitivity: A primary limitation noted is relatively high limits of detection (LOD) compared to some lab-based techniques [1]. For example, a fluorescence sensing method for TNT reports an LOD of 0.03 ng/μL with a response time of under 5 seconds [10].

- Container Interference: Studies confirm that analytes can be detected through both glass and plastic containers, a crucial feature for safe explosives handling [1].

- Data Quality: Instruments with wider spectral ranges, such as those extending below 400 cm⁻¹, allow for detection of more detailed peaks, improving identification confidence [1].

Experimental Protocols for Explosives Analysis

Protocol: Detection of Intact Explosives via Handheld Raman Spectroscopy

This protocol is adapted from peer-reviewed evaluation of handheld Raman spectrometers for detecting intact explosives like TNT, ammonium nitrate (AN), nitromethane (NM), and smokeless powder components [1].

3.1.1 Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials for Explosives Analysis by Raman Spectroscopy

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Handheld Raman Spectrometer | Molecular analysis of samples | E.g., Rigaku ResQ-CQL with 200-2500 cm⁻¹ range [1] |

| Explosives Analytical Standards | Provide known reference materials for identification and calibration | TNT, AN, NM, Diphenylamine (DPA), Ethyl Centralite (EC) [1] |

| Acetone (HPLC Grade) | Solvent for preparing standard solutions of solid analytes | Used for creating concentration gradients [1] |

| Glass and Plastic Vials | Containment for samples during analysis; used for interference study | Evaluate spectral contribution from container materials [1] |

| Authentic Explosive Samples | Validate method performance with real-world samples | TNT flakes, ANFO, smokeless powder [1] |

3.1.2 Procedure

- Instrument Preparation: Power on the handheld Raman spectrometer and allow it to initialize. Perform a calibration check according to the manufacturer's instructions to ensure spectral accuracy.

- Standard Preparation:

- For solid analytes (e.g., DPA, AN), prepare a serial dilution in acetone to create a concentration gradient for sensitivity assessment [1].

- For liquid analytes (e.g., nitromethane), dilutions can be made as needed.

- Transfer standards into glass and plastic vials for analysis.

- Spectral Acquisition:

- Place the spectrometer probe in direct contact with or at the specified distance from the sample vial.

- For each sample, acquire Raman spectra. Typical integration times range from a few seconds to minutes, depending on signal strength.

- For each analyte and concentration, collect multiple spectra (e.g., n=3-5) to assess repeatability.

- Library Matching: Compare the acquired spectra against the instrument's pre-loaded spectral library for preliminary identification.

- Data Analysis: Assess the spectra for reproducibility of peak location and intensity. Overlay spectra from different concentrations to visualize the relationship between peak intensity and analyte concentration [1].

Diagram 1: Raman Analysis Workflow

Protocol: Trace Explosive Detection Using Fluorescence Sensing

This protocol is based on a recent study utilizing a fluorescent sensor and time-series classification for detecting trace TNT [10].

3.2.1 Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

- Fluorescent Sensing Material: LPCMP3, a conjugated microporous polymer synthesized via palladium-catalyzed Buchwald-Hartwig cross-coupling [10].

- Quartz Wafer: Substrate for the fluorescent film.

- Tetrahydrofuran (THF): Solvent for preparing the fluorescent material solution.

- Spin Coater: Used to create a uniform fluorescent film on the quartz wafer (e.g., 5000 rpm for 1 minute) [10].

- Trace TNT Samples: TNT acetone solutions at varying concentrations (e.g., from stock to low concentrations like 0.03 ng/μL).

- UV Light Source: To excite the fluorescent film at its maximum absorption (e.g., 400 nm).

3.2.2 Procedure

- Fluorescent Film Fabrication:

- Dissolve 10 mg of LPCMP3 solid in 1 mL of THF. Protect from light and let stand for 30 minutes until fully dissolved.

- Pipette 20 μL of the 0.5 mg/mL solution onto a clean quartz wafer.

- Use a spin coater at 5000 rpm for 1 minute to create a uniform film. Dry naturally in a dust-free environment or bake at 60°C for 15 minutes [10].

- Sensor Integration and Testing:

- Integrate the prepared fluorescent film into a custom or commercial fluorescence detection system.

- Expose the sensor to TNT acetone solutions of different concentrations. The mechanism is Photoinduced Electron Transfer (PET), where electrons transfer from LPCMP3 to TNT, causing fluorescence quenching [10].

- Record the fluorescence response over time.

- Data Processing and Classification:

- Process the obtained time-series fluorescence data.

- Calculate similarity measures, such as the Spearman correlation coefficient and Derivative Dynamic Time Warping (DDTW) distance, to classify the detection results and differentiate TNT from other substances [10].

Diagram 2: Fluorescence Sensing Workflow

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Handling Portable Instrumentation Data

Data acquired from portable spectrometers is often noisier than data from laboratory instrumentation [11]. Therefore, appropriate mathematical handling and spectral processing are essential to extract meaningful information.

- Spectral Pre-processing: Techniques such as smoothing, baseline correction, and normalization are typically required to improve signal-to-noise ratio before further analysis.

- Multivariate Analysis: For complex samples like contaminated plants or explosive mixtures, Multivariate Statistical Process Control (MSPC) techniques can effectively identify spectral effects caused by pollutants or specific compounds [11].

- Similarity Measures for Classification: For fluorescence-based trace detection, time-series similarity measures like the Spearman correlation coefficient and Derivative Dynamic Time Warping (DDTW) distance have been shown to effectively classify results, distinguishing target explosives from interferents [10].

Practical Considerations for Field Deployment

- Limits of Detection (LOD): Researchers must be aware that portable instruments may have higher LODs than benchtop systems. This dictates the minimum detectable quantity of an explosive material in the field [1].

- Container Interference: While analysis through glass and plastic is feasible, the material of the container may contribute to the spectral background and should be accounted for during interpretation [1].

- Fluorescence: In Raman spectroscopy, some samples may fluoresce, overwhelming the weaker Raman signal. Instruments with longer wavelength lasers (e.g., 1064 nm) can mitigate this issue [1].

Portable spectrometers represent a transformative toolset for field-based analysis, particularly in the critical domain of explosives detection and identification. The transition from benchtop to handheld and wearable devices empowers researchers and first responders with immediate analytical capabilities directly at the point of need. While considerations around sensitivity and data noise exist, established experimental protocols and robust data analysis methods ensure reliable results. The continued advancement of these technologies, coupled with standardized application notes as outlined herein, will further enhance their role in ensuring safety and advancing scientific research in field settings.

The accurate and rapid identification of explosives and their precursors in field settings is a critical requirement for forensic science, homeland security, and counter-terrorism operations worldwide [12] [13]. The proliferation of improvised explosive devices (IEDs) has intensified the need for portable, reliable analytical tools that can provide immediate, actionable intelligence to first responders and investigators [12] [1]. Spectroscopic techniques have emerged as powerful solutions for this challenge, enabling non-destructive, rapid chemical identification of energetic materials with minimal sample preparation [13] [14]. This application note details the operational protocols, capabilities, and experimental methodologies for five core spectroscopic technologies—Raman, Infrared (IR), Near-Infrared (NIR), Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS), and X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF)—within the context of field-deployable explosives fingerprinting.

The detection of explosives requires techniques capable of identifying both organic and inorganic compounds, as well as complex mixtures. The table below summarizes the fundamental principles, key applications, and specific limitations of each technology for explosives analysis.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Spectroscopic Techniques for Explosives Detection

| Technique | Fundamental Principle | Key Explosives Applications | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Raman | Measures inelastically scattered light from molecular vibrations [12] [15]. | Identification of organic explosives (TNT, RDX, TATP, HMTD) through sealed containers; analysis of aqueous solutions and light-colored powders [12] [1] [15]. | Fluorescence interference; potential laser-induced heating of energetic materials; relatively high limits of detection for some handheld units [1] [13] [14]. |

| IR (FT-IR) | Measures absorption of infrared light by molecular bonds [12] [2]. | Identification of polar covalent bonds; effective for fluorescent samples; analysis of explosives like Semtex and Detasheet [12] [2]. | Requires sampling and contact; signal absorption by water; limited penetration through packaging [12] [14]. |

| NIR | Measures overtone and combination vibrations of C-H, O-H, and N-H bonds [14]. | Identification of intact organic and inorganic energetic materials and their mixtures; non-invasive screening of precursors [16] [14]. | Complex spectra requiring chemometrics; challenging for pyrotechnic mixtures and some inorganic materials [14]. |

| LIBS | Analyzes atomic emission from laser-generated plasma to determine elemental composition [13] [17] [18]. | Elemental analysis of post-blast residues; detection of inorganic components (e.g., in ANFO); geochemical fingerprinting of precursor sources [13] [17]. | Semi-destructive (micro-ablation); matrix effects; limited molecular information [17]. |

| XRF | Measures secondary X-ray emission from excited atoms to determine elemental composition [17]. | Elemental analysis of explosives containing specific elements (e.g., chlorates, perchlorates); often paired with molecular techniques [17]. | Limited to elemental analysis; poor sensitivity for light elements; radiation safety concerns [17]. |

Experimental Protocols for Explosives Fingerprinting

Protocol: Handheld Raman Spectroscopy for Intact Explosives

Objective: To reliably identify common intact explosives and their precursors using a handheld Raman spectrometer [1].

Materials and Reagents:

- Handheld Raman spectrometer (e.g., Rigaku ResQ-CQL or Field Forensics HandyRam) [1]

- Analytical standards of target explosives: TNT, Nitromethane (NM), Ammonium Nitrate (AN), Diphenylamine (DPA), Ethyl Centralite (EC), Methyl Centralite (MC) [1]

- Glass vials or plastic containers for containment studies

- Acetone or acetonitrile (for solvent studies) [1]

Procedure:

- Instrument Calibration: Perform wavelength and intensity calibration according to the manufacturer's specifications using the built-in standards [1].

- Sample Presentation:

- Spectral Acquisition:

- Position the spectrometer probe head flush with the container or sample surface.

- Acquire spectra with integration times typically between 1-10 seconds; multiple accumulations may be used to improve signal-to-noise ratio [1].

- Data Analysis:

Notes: The Rigaku ResQ-CQL has demonstrated better resolution and lower fluorescence across various analytes compared to other handheld units. A key limitation is the relatively high limit of detection, requiring sufficient sample quantity for positive identification [1].

Protocol: Portable NIR Spectroscopy with Multivariate Analysis

Objective: To perform rapid, on-scene identification of a broad range of intact energetic materials using portable NIR spectroscopy and chemometric models [16] [14].

Materials and Reagents:

- Portable FT-NIR analyzer (e.g., Si-Ware NeoSpectra scanner, 1350–2550 nm range) [14]

- Chemical standards: Nitro-aromatics (TNT), nitro-amines (RDX, HMX), nitrate esters (PETN, ETN), peroxides (TATP), and inorganic oxidizers [14]

- Multivariate data analysis software (e.g., in-house developed chemometric models)

Procedure:

- Model Development:

- Collect NIR reflectance spectra from a comprehensive library of known explosive compounds and precursors.

- Pre-process raw spectra using Standard Normal Variate (SNV) and Savitzky-Golay derivatives to minimize scattering effects and enhance spectral features [14].

- Develop a multi-stage classification model incorporating Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) and Net Analyte Signal (NAS) calculations to achieve high specificity [14].

- Field Deployment and Analysis:

- Position the portable NIR spectrometer in direct contact with the sample or at a close, fixed distance.

- Acquire reflectance spectrum with a single measurement taking seconds.

- The processed spectrum is automatically evaluated against the pre-trained chemometric model.

- The system provides identification results with a probabilistic confidence score [14].

Notes: This approach has demonstrated high predictive accuracy for precursor quantification (e.g., RMSEP of 0.96% for hydrogen peroxide) and can correctly distinguish between chemically similar compounds like ETN and PETN. However, it performs poorly with pyrotechnic mixtures like black powder [16] [14].

Figure 1: NIR Explosives Analysis Workflow

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table catalogues critical chemical standards and materials required for developing and validating spectroscopic methods for explosives detection.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Explosives Fingerprinting

| Reagent/Material | Chemical Class | Research Function | Relevant Techniques |

|---|---|---|---|

| TNT (Trinitrotoluene) [19] [1] | Nitro-aromatic | Standard for military-grade explosives; benchmark for SERS and Raman studies [19] [13]. | Raman, NIR, SERS [19] [1] [13] |

| RDX (Cyclotrimethylenetrinitramine) & PETN (Pentaerythritol Tetranitrate) [13] [14] | Nitro-amine & Nitrate Ester | Standards for plastic explosives (e.g., C4, Semtex); used in mixture analysis [13] [14]. | Raman, NIR, THz [13] [14] |

| TATP (Triacetone Triperoxide) & HMTD [19] [15] | Peroxide | Standards for home-made explosives (HMEs); key targets for non-invasive detection [19] [15]. | Raman, SERS [19] [15] |

| Ammonium Nitrate (AN) & Nitromethane (NM) [16] [1] | Inorganic Oxidizer & Organic Fuel | Precursors for ANFO and other HMEs; targets for regulatory detection [16] [1]. | NIR, Raman, LIBS [16] [1] |

| Diphenylamine (DPA), Ethyl Centralite (EC) [1] | Stabilizer | Markers for smokeless powder identification [1]. | Raman, LIBS [1] |

| Hydrogen Peroxide [16] | Oxidizer | Key precursor for peroxide-based HMEs; target for quantitative analysis [16]. | NIR [16] |

Advanced Data Analysis and Chemometrics

The complexity of spectroscopic data, particularly for mixtures and complex matrices, necessitates advanced chemometric processing for reliable identification [2] [14]. The workflow for data analysis involves multiple stages to ensure accuracy.

Figure 2: Chemometric Data Analysis Workflow

Key Algorithms and Their Functions:

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): Reduces spectral dimensionality and identifies key variance patterns, useful for clustering similar explosive types and detecting outliers [2] [14].

- Partial Least Squares - Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA): A supervised method used for classifying explosives into predefined categories (e.g., peroxide vs. nitro-aromatic) and quantifying component concentrations in mixtures [13] [2].

- Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA): Often applied after PCA to maximize separation between different classes of explosives, enhancing classification reliability in portable NIR instruments [14].

- Machine Learning (Random Forest, SVM): Non-linear algorithms that can handle complex, high-dimensional spectral data, improving model robustness for real-world samples with contamination or aging [16] [2].

The integration of portable spectroscopy with advanced chemometrics has significantly advanced the field of explosives fingerprinting, enabling rapid, on-scene identification that was previously confined to laboratory analysis. Each technique offers distinct advantages: Raman and NIR provide excellent molecular specificity with minimal sample preparation, while LIBS and XRF deliver crucial elemental information. The future of field explosives analysis lies in the strategic combination of these complementary technologies and the continued refinement of chemometric models through machine learning, providing first responders and forensic professionals with an increasingly powerful toolkit for combating explosive threats.

Portable spectroscopy has emerged as a transformative capability for field-based analysis of explosives, addressing critical needs in security, forensic investigations, and environmental monitoring. These techniques enable rapid, on-site identification of hazardous materials without the delays associated with laboratory transport and processing. For researchers and security professionals, three advantages stand out as particularly impactful: the non-destructive nature of analysis, exceptional speed of detection, and the unique capability for container interrogation. This application note details the experimental protocols and technical foundations underlying these advantages, providing a framework for their implementation in field operations and research settings. The integration of these capabilities allows for real-time decision making in scenarios ranging from security checkpoints to post-blast investigations, significantly enhancing operational effectiveness while maintaining analytical rigor.

Technical Advantages in Detail

Non-destructive Analysis

Non-destructive analysis preserves evidence integrity, maintains sample availability for subsequent tests, and enables repeated measurements on the same specimen. This is particularly crucial in forensic investigations where sample preservation for legal proceedings is paramount, and in security screening where the contents of suspicious packages must be identified without triggering detonation.

Mechanism: Techniques like Raman and Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy operate by measuring the interaction of electromagnetic radiation with molecular bonds. Raman spectroscopy detects inelastically scattered photons resulting from vibrational energy transitions, while FTIR measures absorption of infrared light at characteristic frequencies. Both methods probe molecular structure without consuming or permanently altering the sample. As demonstrated in cultural heritage conservation, these approaches can analyze precious artifacts without damage, a principle directly transferable to explosives investigation where evidence preservation is critical [20].

Experimental Consideration: The non-destructive capability depends on appropriate power settings, especially for potentially photosensitive materials. While the methods are inherently non-destructive, excessive laser power in Raman spectroscopy or intense IR sources in FTIR could potentially degrade sensitive explosive compounds if not properly calibrated.

Speed and Real-Time Detection

The rapid analysis capability of portable spectrometers provides critical time advantages in field operations, enabling near-instantaneous identification of potential threats with detection times ranging from seconds to minutes rather than hours or days required for laboratory analysis.

Quantitative Performance: Recent advancements demonstrate remarkable speed metrics across various spectroscopic techniques. Fluorescence sensing has achieved detection of TNT acetone solution with a response time of less than 5 seconds and recovery response under 1 minute [10]. Quantum Cascade Laser (QCL) based infrared microscopes can acquire chemical images at rates of 4.5 mm² per second, enabling rapid mapping of suspect surfaces [21]. Portable NIR systems provide real-time, non-invasive detection of intact energetic materials, significantly enhancing on-site forensic capabilities [2].

Operational Impact: This rapid analysis translates directly to operational efficiency. Field teams can conduct more comprehensive surveys in less time, while security checkpoints can maintain throughput without compromising detection capabilities. The immediacy of results enables iterative testing approaches, where initial findings can be immediately verified through complementary analyses.

Container Interrogation

Container interrogation represents one of the most significant operational advantages of spectroscopic methods, enabling detection of explosive materials through various barriers including plastic, glass, paper, and thin metals without physical breach.

Physical Basis: This capability leverages the transmission properties of specific electromagnetic wavelengths. Near-infrared (NIR) radiation penetrates many common container materials while still interacting with the contents sufficiently to generate identifiable spectral signatures. Raman spectroscopy can similarly probe contents through transparent or semi-transparent barriers, though signal attenuation must be considered.

Implementation Protocols: Successful container interrogation requires methodological adjustments compared to direct sampling. Signal intensity is necessarily reduced when measuring through barriers, necessitating potentially longer integration times or slightly increased power settings. The background signal from the container material itself must be characterized and subtracted for accurate identification. As noted in reviews of field-portable instrumentation, this capability is particularly valuable for emergency response and military operations where immediate chemical identification through packaging can determine safety protocols [22].

Table 1: Comparison of Key Spectroscopic Techniques for Explosives Detection

| Technique | Non-destructive | Typical Analysis Time | Container Interrogation Capability | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FTIR | Yes | 30-60 seconds | Limited to thin, IR-transparent materials | Interference from environmental contaminants [2] |

| ATR-FTIR | Yes | 10-30 seconds | Surface contact required | Limited penetration depth [2] |

| NIR Spectroscopy | Yes | 5-15 seconds | Excellent through various containers | Lower spectral resolution vs. FTIR [2] |

| Raman | Yes | 10-30 seconds | Good through transparent materials | Fluorescence interference possible [10] |

| Fluorescence Sensing | Yes | <5 seconds | Limited by optical access | Specific to fluorescent/quenching compounds [10] |

Experimental Protocols

General Field Deployment Workflow

The following workflow outlines the standard operating procedure for field deployment of portable spectrometers for explosives detection. This protocol integrates the key advantages of non-destructive analysis, speed, and container interrogation into a cohesive operational framework.

Protocol for Fluorescence-Based Trace Explosive Detection

This specific protocol details the experimental procedure for detecting trace explosives using fluorescence sensing, based on recent research demonstrating high sensitivity to TNT and related nitroaromatic compounds [10].

Principle: The method utilizes fluorescent sensing materials that undergo fluorescence quenching via photoinduced electron transfer when nitroaromatic explosives like TNT are present. The conjugated networks of the fluorescent material undergo π-π stacking interactions with nitroaromatics, leading to measurable decreases in fluorescence intensity.

Materials and Equipment:

- Portable fluorescence spectrometer with appropriate excitation/emission capabilities

- Fluorescent sensing material (e.g., LPCMP3 or similar conjugated polymer)

- Quartz substrates for film deposition

- Spin coater (e.g., TC-218 or equivalent)

- Micropipettes (1-20 μL range)

- Solvents: tetrahydrofuran (THF), acetone

- Standard solutions: TNT in acetone at various concentrations (e.g., 0.01-100 ng/μL)

- Negative controls: common chemical reagents without explosive content

Procedure:

- Fluorescent Film Preparation:

- Dissolve 10 mg of fluorescent sensing material in 1 mL THF

- Protect from light and allow complete dissolution (30 minutes standing)

- Prepare 0.5 mg/mL working solution by appropriate dilution

- Deposit 20 μL onto quartz wafer using micropipette

- Spin-coat at 5000 rpm for 1 minute using spin coater

- Cure film by either:

- Natural drying in dust-free environment (30 minutes), OR

- Oven baking at 60°C for 15 minutes

System Calibration:

- Mount fluorescent film in spectrometer sample holder

- Establish baseline fluorescence with pure solvent

- Measure response series with TNT standards (0.01, 0.03, 0.1, 0.3, 1.0, 3.0 ng/μL)

- Determine limit of detection (typically ~0.03 ng/μL for TNT acetone solution)

- Verify response time (<5 seconds) and recovery time (<1 minute)

Sample Analysis:

- Position unknown sample in proximity to fluorescent film

- Record fluorescence intensity over time (minimum 30-second acquisition)

- Compare temporal response pattern to calibrated standards

- Apply similarity measures (Spearman correlation + DDTW distance) for classification

Data Analysis:

- Calculate similarity measures between unknown and reference patterns

- Classify based on integrated Spearman correlation + DDTW distance

- Report identification confidence based on similarity thresholds

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Explosives Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| LPCMP3 Fluorescent Polymer | Fluorescence sensing element for nitroaromatics | Exhibits maximum absorption at 400 nm, emission at 537 nm; susceptible to photobleaching without proper stabilization [10] |

| ATR-FTIR Crystal | Internal reflection element for surface analysis | Enables minimal sample preparation; superior surface sensitivity for solid-phase analysis [2] |

| Quantum Cascade Laser (QCL) | IR source for high-sensitivity microscopy | Provides spectral range 1800-950 cm⁻¹; enables imaging rates of 4.5 mm² per second [21] |

| Portable NIR Spectrometer | Field-deployable instrument for molecular analysis | Effective for container interrogation; requires chemometric models for data interpretation [2] |

| Chemometric Software | Multivariate data analysis platform | Enables PCA, LDA, PLS-DA for classification; essential for complex mixture analysis [2] |

Protocol for IR Spectroscopy with Chemometric Analysis

This protocol outlines the procedure for utilizing portable IR spectroscopy combined with chemometric analysis for explosive identification and classification, particularly valuable for complex mixtures and contaminated samples.

Principle: IR spectroscopy probes molecular vibrations through infrared light absorption, generating unique spectral fingerprints for different explosive compounds. Chemometric analysis enhances discrimination capability through multivariate statistical methods.

Materials and Equipment:

- Portable FTIR or ATR-FTIR spectrometer

- Chemometric software package (PCA, LDA, PLS-DA capabilities)

- Reference spectral library of explosive compounds

- Sample preparation tools (where applicable)

- Personal protective equipment

Procedure:

- Instrument Preparation:

- Initialize portable IR spectrometer according to manufacturer specifications

- Perform background scan with clean ATR crystal or appropriate reference

- Verify instrument performance with standard reference material

Sample Collection and Preparation:

- For solid residues: transfer minimal material to ATR crystal using clean probe

- For liquid samples: apply directly to crystal or use appropriate liquid cell

- For surface analysis: ensure good contact between sample and crystal

- Minimize sample preparation to maintain field applicability

Spectral Acquisition:

- Acquire spectra in appropriate range (typically 4000-650 cm⁻¹)

- Use sufficient scans (typically 16-64) to ensure adequate signal-to-noise

- Maintain consistent pressure for ATR measurements

- Record environmental conditions (temperature, humidity)

Chemometric Analysis:

- Preprocess spectra (baseline correction, normalization, derivative processing)

- Perform Principal Component Analysis (PCA) for exploratory data analysis

- Apply Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) or Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA) for classification

- Validate model performance with test set or cross-validation

- Report classification confidence metrics

Data Interpretation:

- Compare unknown spectra to reference library

- Evaluate chemometric classification results

- Consider environmental contaminants and matrix effects in final assessment

Data Analysis and Interpretation

The analytical power of portable spectroscopy for explosives detection is substantially enhanced through advanced data processing techniques. Effective interpretation requires both spectral analysis and statistical validation to ensure reliable identification.

Similarity Measures for Time Series Classification: For fluorescence-based detection generating temporal response data, similarity measures provide robust classification capabilities. The integrated approach combining Spearman correlation coefficient and Derivative Dynamic Time Warping (DDTW) distance has demonstrated effective classification of explosive detection results [10]. This combined approach accommodates variations in response timing while maintaining sensitivity to characteristic response patterns.

Chemometric Integration: The fusion of spectroscopic techniques with chemometric methodologies has significantly enhanced forensic capabilities for homemade explosives (HMEs) classification [2]. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) enables visualization of spectral clustering, while Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) and Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA) provide supervised classification models. These approaches have achieved classification accuracies exceeding 92.5% for ammonium nitrate-based explosives when combining ATR-FTIR with trace elemental analysis [2].

Quantitative Performance Metrics: The analytical performance of these methods is demonstrated through specific quantitative metrics. Fluorescence sensing achieves detection limits of 0.03 ng/μL for TNT with response times under 5 seconds [10]. Portable NIR systems enable real-time, non-invasive detection of intact energetic materials [2]. These performance characteristics directly support the key advantages of speed and sensitivity in field deployment scenarios.

The integration of non-destructive analysis, rapid detection capabilities, and container interrogation positions portable spectroscopy as an indispensable methodology for field-based explosives analysis. The experimental protocols detailed in this application note provide researchers and security professionals with validated approaches for implementing these techniques in operational environments. As portable instrumentation continues to advance, with ongoing developments in miniaturization, sensitivity, and data analysis capabilities, the role of these techniques in security, forensic, and environmental applications will continue to expand. The combination of robust analytical methods with advanced data processing represents the future pathway for enhanced field-based explosives detection and identification.

The field of hazardous material analysis, particularly for explosives and security threats, is undergoing a significant transformation marked by a decisive shift from traditional laboratory-based analysis to on-site detection technologies. This transition is driven by the critical need for rapid decision-making in field settings including crime scenes, security checkpoints, and post-blast investigations, where time-sensitive results can profoundly impact public safety and investigative outcomes [23]. Portable spectroscopy techniques stand at the forefront of this shift, enabling researchers and first responders to obtain analytical results in real-time without the delays associated with transporting samples to fixed laboratories. The demand for these technologies is further amplified by evolving global security challenges, including the use of improvised explosives and the need to analyze complex post-blast residues in challenging environments [24]. This application note details the current market trends in portable spectroscopy and provides structured experimental protocols for their deployment in field-based explosives analysis.

Key Technologies Driving On-Site Analysis

The advancement of on-site analysis is powered by several portable spectroscopic techniques, each offering unique capabilities for the detection and identification of explosives and related hazardous materials. The table below summarizes the core technologies, their underlying principles, and application-specific advantages.

Table 1: Key Portable Spectroscopy Techniques for Explosives Analysis

| Technology | Principle of Operation | Key Advantages for Field Use | Example Explosives Analyzed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) | Enhances Raman signal of trace molecules adsorbed on nanostructured noble metal surfaces [25]. | Ultra-high sensitivity for trace explosives, rapid analysis (seconds to minutes), fingerprint identification [25]. | RDX, TNT, Nitroglycerin [25]. |

| Portable X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) | Measures secondary X-rays emitted from a sample to determine its elemental composition [26]. | Rapid, non-destructive elemental analysis; penetrates surface contaminants like blood [26]. | Identification of elemental components in precursors or post-blast residues [26]. |

| Gas Chromatography-Vacuum Ultraviolet Spectroscopy (GC-VUV) | Separates mixture components via GC followed by absorption detection in the VUV range (100-200 nm) [23]. | High selectivity in complex mixtures, specific identification of compounds, library matching [23]. | Intact smokeless powder particles, nitrated compounds [23]. |

These technologies are increasingly being integrated into user-friendly, portable equipment, moving from merely detecting the presence of explosives to providing confident identification of specific compounds directly at the point of need [25] [23].

Experimental Protocols for Field-Based Explosives Analysis

Protocol for SERS-Based Trace Explosives Detection

Principle: This protocol utilizes plasmonic nanostructures to significantly amplify the inherently weak Raman scattering signal from molecules of trace explosives adsorbed on the surface, enabling their identification at ultralow concentrations [25].

Workflow Diagram: SERS-Based Trace Explosives Detection

Materials and Reagents:

- Portable Raman Spectrometer: Integrated with a SERS substrate module.

- SERS-Active Substrits: Nobel metal nanoparticles (e.g., gold or silver) on solid supports [25].

- Sampling Kits: Include sterile swabs (e.g., nylon or cotton) and gloves to prevent contamination.

- Calibration Standards: Solutions of known explosives for instrument validation.

Procedure:

- Instrument Calibration: Turn on the portable SERS spectrometer and perform a daily calibration check using the provided internal standard or an external calibration standard as per the manufacturer's instructions.

- Sample Collection: Using a clean swab, firmly wipe the suspected contaminated surface (e.g., luggage handle, post-blast debris) using a predefined pattern and pressure. For porous or irregular surfaces, employ a multi-swab technique to maximize sample recovery.

- Sample Transfer: Gently roll the collected sample swab over the active area of the SERS substrate. Alternatively, if the substrate is a chip, place the swabbed material in contact with it. Ensure uniform contact for maximum signal enhancement.

- SERS Measurement: Place the prepared SERS substrate into the spectrometer's sample chamber. Initiate the measurement sequence. A typical measurement accumulates signal for 5-20 seconds to ensure adequate signal-to-noise ratio while maintaining speed [25].

- Data Analysis and Reporting: The instrument software automatically processes the raw spectrum (e.g., baseline correction, noise filtering). The resulting spectrum is compared against an integrated library of explosive reference materials. Report the match quality (e.g., hit quality index) and the identified compound.

Protocol for Elemental Contamination Assessment Using Portable XRF

Principle: This method uses a portable XRF device to irradiate a sample with primary X-rays, causing the ejection of inner-shell electrons. As outer-shell electrons fill the vacancies, element-specific fluorescent X-rays are emitted and detected, allowing for qualitative and quantitative analysis of heavy atoms [26].

Workflow Diagram: XRF Contamination Assessment

Materials and Reagents:

- Portable XRF Analyzer: Equipped with a silicon drift detector and a low-power X-ray tube.

- Test Stand (optional): For consistent sample positioning during method validation.

- Calibration Standards: Certified reference materials with known concentrations of target elements (e.g., Pb) for constructing calibration curves [26].

- Collimator: To define the analysis area and minimize background signal from the surrounding area.

Procedure:

- Site Preparation and Safety: Clearly demarcate the analysis area. Ensure the XRF beam is directed away from personnel. The operator must wear a dosimeter.

- Instrument Setup: Power on the XRF analyzer. Select the appropriate analytical mode (e.g., "Soil" or "Alloy") and ensure the instrument is calibrated. Attach the collimator if a small area is to be analyzed.

- Parameter Selection: Set the X-ray tube operating conditions (voltage and current) and select the appropriate filter to optimize excitation for the target elements (e.g., heavy atoms like Pb as a model for Pu) [26]. Set the counting time based on the desired detection limit and dose constraints (e.g., 5-20 seconds, corresponding to an equivalent dose of 16.5-66.0 mSv to the skin) [26].

- Measurement: Place the analyzer's measurement window in direct and firm contact with the sample surface (e.g., a wound phantom or contaminated material). Activate the measurement and hold the device steady until the analysis is complete.

- Data Interpretation: The instrument software will display a spectrum with peaks corresponding to elements present. Use the integrated software to quantify the concentration of the target element, typically based on fundamental parameter algorithms or pre-loaded calibration curves. For complex matrices like rust, the thickness of the material layer must be considered for accurate quantification [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful on-site analysis relies on a suite of specialized materials and reagents. The following table details key components of the field researcher's toolkit.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Field Explosives Analysis

| Item | Function/Description | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| SERS Substrates | Nanostructured surfaces (e.g., Au/Ag nanoparticles on solid supports) that provide massive signal enhancement for Raman spectroscopy [25]. | Critical for achieving the ultra-high sensitivity required for trace-level explosive vapor and particulate detection. Stability and shelf-life are key performance factors. |

| Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) Sorbents | Materials like Oasis HLB and Isolute ENV+ used to isolate and pre-concentrate explosive analytes from complex matrices (e.g., soil, wastewater) [24]. | Significantly improves recovery and limits of detection in complex post-blast samples; a dual-sorbent approach can minimize matrix effects [24]. |

| Calibration Standards & Color Targets | Solutions of certified explosive reference materials and physical color calibration targets (e.g., RAL Design System Plus) [28]. | Essential for instrument validation, quality control, and ensuring the colorimetric accuracy of portable spectrophotometers and other detection systems. |

| Sampling Swabs & Wipes | Sterile, low-background collection materials (e.g., nylon flocked swabs) for retrieving particulates from surfaces. | The choice of material can affect sample recovery efficiency and minimize background interference during instrumental analysis. |

The migration of analytical capabilities from the central laboratory to the field is a definitive trend in explosives and security science. Technologies like portable SERS, XRF, and GC-VUV are maturing to offer a powerful combination of sensitivity, selectivity, and speed, meeting the rigorous demands of on-site analysis [25] [26] [23]. The experimental protocols and toolkit detailed in this document provide a framework for researchers to implement these techniques effectively. As the security landscape continues to evolve with the proliferation of homemade explosives and complex post-blast scenarios [24], the further development and integration of these portable spectroscopic methods will be paramount. Future progress will likely focus on enhancing the ruggedness and connectivity of devices, expanding reference libraries, and developing even more sensitive and selective substrates and sampling protocols to stay ahead of emerging threats.

Methodologies and Real-World Applications for Intact Explosives and Residues

The rapid and reliable identification of intact explosives in the field is a critical challenge for forensic investigators, first responders, and security personnel. Portable Raman spectroscopy has emerged as a premier analytical technique for this purpose, offering a unique combination of non-destructive analysis, minimal sample preparation, and the ability to identify chemicals through sealed containers [1] [12]. This application note details the methodologies and capabilities of handheld Raman spectrometers for detecting key explosives including ammonium nitrate (AN), 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene (TNT), nitromethane (NM), and signature components of smokeless powder (diphenylamine/DPA, ethyl centralite/EC, and methyl centralite/MC). The content is framed within a broader research context advocating for orthogonal analytical techniques to enhance detection accuracy and reliability in field-based explosives analysis [3] [29].

Key Explosives and Their Raman Detection

Target Analytes and Spectral Features

The detection of homemade explosives (HMEs) presents a particular challenge due to the wide array of potential organic and inorganic components. Ammonium nitrate (AN) is a common oxidizer in HMEs like ANFO (Ammonium Nitrate/Fuel Oil). TNT is a traditional military explosive. Nitromethane is a liquid explosive often used in hobby fuels, and smokeless powder components (DPA, EC, MC) are stabilizers whose presence is indicative of this propellant, which can be misused as an HME [1] [29].

Table 1: Characteristic Raman Peaks of Target Explosives and Related Compounds

| Compound | Characteristic Raman Shifts (cm⁻¹) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Ammonium Nitrate (AN) | 1,040 (vs), 715 (m) [29] | Inorganic oxidizer |

| 2,4,6-Trinitrotoluene (TNT) | 1,366 (s), 1,536 (s) [29] | Nitroaromatic explosive |

| Nitromethane (NM) | 917 (s), 1,406 (s) [1] | Liquid organic explosive |

| Diphenylamine (DPA) | 1,002 (s), 1,300 (m) [1] | Smokeless powder stabilizer |

| Ethyl Centralite (EC) | 1,231 (s), 1,596 (m) [1] | Smokeless powder stabilizer |

| Methyl Centralite (MC) | 1,226 (s), 1,594 (m) [1] | Smokeless powder stabilizer |

| Pentaerythritol Tetranitrate (PETN) | 1,292 (s), 1,490 (m) [29] | High explosive |

Performance Comparison of Handheld Raman Systems

The core analytical performance of handheld Raman spectrometers can vary significantly based on the laser excitation wavelength and internal design. A comparative evaluation of two handheld instruments, the Rigaku ResQ-CQL (1064 nm) and the Field Forensics HandyRam (785 nm), provides critical insights for method selection [1] [30].

Table 2: Comparison of Handheld Raman Spectrometer Performance

| Parameter | Rigaku ResQ-CQL (1064 nm) | Field Forensics HandyRam (785 nm) |

|---|---|---|

| Laser Wavelength | 1064 nm | 785 nm |

| Key Advantage | Lower fluorescence, higher signal for most explosives [1] | Commonly available technology |

| Observed Signal | High intensity, low background [1] | Lower intensity, exhibited fluorescence requiring baseline correction [1] |

| Spectral Resolution | Better resolution, more detailed peaks below 400 cm⁻¹ [1] | Standard resolution |

| Overall Performance | Superior for the tested explosive compounds [1] | Acceptable, but with limitations for fluorescent samples |

The 1064 nm laser of the Rigaku system provided a better balance between low background fluorescence and a high analyte signal, producing spectra with superior resolution [1]. While 785 nm is a common excitation wavelength, 532 nm systems are also gaining traction due to a stronger inherent Raman signal, though this can sometimes come with an increased risk of fluorescence [31].

Experimental Protocols for Explosives Analysis

General Sample Analysis Workflow

The following protocol is adapted from peer-reviewed evaluations of handheld Raman spectrometers for intact explosives [1]. The entire procedure, from sample preparation to identification, is designed for field deployment and can be completed within minutes.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Sample Preparation (Safety First):

- Wear appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE).

- For sealed containers: Analyze the substance directly through the glass or plastic wall. Raman spectroscopy can typically analyze samples through transparent or translucent containers without opening them, a significant safety advantage for potential explosives [1] [12].

- For loose solids: Place a small amount (mg quantity) in a glass vial or on a non-fluorescent surface.

Instrument Preparation:

- Power on the handheld Raman spectrometer.

- Ensure the battery is sufficiently charged for field operation.

- Allow the instrument to initialize and perform its self-checks.

Performance Check (Quality Control):

- Prior to analysis, validate instrument performance using a built-in validation standard or a known reference material, following the manufacturer's procedure [32]. This verifies proper calibration of the spectrometer, mass analyzer, and library search function.

Spectral Acquisition:

- Position the instrument's probe head flush against the container wall or directly above the solid sample. For dark-colored or sensitive explosives (e.g., black powder), avoid keeping the laser on a single spot for an extended period to minimize heat buildup [33].

- Trigger the measurement. Typical acquisition times range from 1 to 30 seconds, depending on the instrument and sample [1] [12].

- The instrument projects a single-wavelength laser onto the sample, collects the inelastically scattered (Raman) light, and generates a spectral graph of intensity versus Raman shift (cm⁻¹).

Data Analysis and Identification:

- The instrument's onboard software automatically compares the acquired sample spectrum against a curated library of reference spectra for explosives and related compounds.

- The software returns a list of potential matches with a corresponding hit quality index (HQI) or similar metric.

- A successful identification is typically indicated by a high HQI and a visual confirmation that the major peaks in the sample spectrum align with the reference.

Advanced Safety Protocol for Sensitive Explosives

The analysis of sensitive primary explosives like triacetone triperoxide (TATP) and black powder carries a risk of ignition from continuous-wave (cw) laser heating, especially for dark-colored substances [33]. A pulsed Raman spectroscopy method has been demonstrated to mitigate this risk.

Pulsed Laser Raman Protocol [33]:

- Instrument Setup: Use a Raman system equipped with a pulsed nanosecond laser (e.g., 532 nm wavelength).

- Parameter Optimization: Set the laser to a low repetition rate (as low as 5 Hz has been shown to be effective) and a controlled pulse energy (~60 µJ).

- Measurement: Irradiate the sensitive explosive sample (TATP, black powder, or mixtures) with the pulsed laser. The short interaction time and lower average power significantly reduce heat accumulation.

- Detection: High-quality Raman spectra can be acquired in short measurement times (integration times of 200-500 ms) without observed ignition, even at a single measurement spot [33].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Successful field analysis requires not only the main instrument but also a suite of supporting materials and reagents.

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Handheld Raman Analysis of Explosives

| Item | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Handheld Raman Spectrometer | Primary tool for non-destructive, in-field chemical identification. | Identification of unknown powders and liquids. |

| Analytical Standards | High-purity reference materials for method validation and library building. | Creating instrument calibration curves; verifying detection limits for TNT, AN, etc. [1] |

| Solvents (Acetone, Acetonitrile) | For dissolving solid analytes to study limits of detection and prepare standard solutions. | Sensitivity studies of smokeless powder stabilizers (DPA, EC) [1] |

| Solid-Phase Microextraction (SPME) Fibers | Pre-concentration of trace-level volatile and semi-volatile analytes from headspace or solution. | Sampling explosive vapors for subsequent analysis by GC-MS or thermal desorption Raman [32]. |

| Glass and Plastic Vials | Standardized, non-fluorescent containers for holding samples during analysis. | Interference studies to confirm detection through container walls [1]. |

| Validation Mixture | A standard solution with known components and concentrations. | Daily performance verification of the portable spectrometer [32]. |

Complementary and Orthogonal Techniques

While powerful, Raman spectroscopy is most effective when used as part of a broader analytical strategy. No single technique can address all detection scenarios.

- Fourier-Transform Infrared (FT-IR) Spectroscopy: FT-IR is highly complementary to Raman. It is particularly effective for materials with polar covalent bonds and fluorescent samples [12]. Used together, Raman and FT-IR provide a wider range of identification.

- Direct Analysis in Real Time-Mass Spectrometry (DART-MS): DART-MS is an ambient ionization technique that requires minimal sample preparation and provides molecular weight and structural information. It is highly effective for organic explosives and can be used orthogonally with Raman to confirm identifications and analyze a broader range of compounds [29].

- Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS): Portable GC-MS provides confirmatory, high-sensitivity identification and is considered a "gold standard" for volatile and semi-volatile organic explosives analysis in the field. It is especially valuable for complex mixtures and trace-level detection [32].

- Ion Mobility Spectrometry (IMS): IMS is a widely deployed trace detection technique known for its high sensitivity (ppt-ppb levels) and rapid analysis, commonly used in airport security for vapor and particulate detection [3].

Handheld Raman spectrometry is a proven, effective technology for the rapid identification of intact explosives like AN, TNT, nitromethane, and smokeless powder components directly in the field. The Rigaku ResQ-CQL with a 1064 nm laser demonstrated superior performance in recent evaluations, offering high signal-to-noise ratios and minimal fluorescence for these target analytes [1]. The methodology is defined by a simple workflow that emphasizes operator safety through non-contact, through-container analysis.

For researchers and professionals, the key to maximizing the utility of handheld Raman lies in understanding its capabilities and limitations. Success depends on selecting the appropriate laser wavelength, being aware of the potential for fluorescence or laser-induced heating, and integrating Raman within a broader analytical framework that includes orthogonal techniques like FT-IR and MS. This multi-technique approach, supported by rigorous experimental protocols, provides the highest level of accuracy and reliability for explosives detection and identification in critical field situations.

Within the framework of research into portable spectroscopy for field-based explosives analysis, the rapid and reliable identification of Homemade Explosives (HMEs) presents a distinct challenge for forensic scientists and first responders. HMEs are often produced from readily available precursors, leading to mixtures with diverse organic and inorganic components that can be colored or impure, complicating their analysis [1] [34]. This application note details the use of Infrared (IR) and Near-Infrared (NIR) spectroscopy as key tools for the non-destructive, in-field identification of intact HMEs and their precursors. We provide validated protocols and data interpretation guides to enable researchers and professionals to quickly and safely characterize these hazardous materials.

Theoretical Principles

Vibrational spectroscopy techniques, including Mid-IR and NIR, are fundamental for identifying functional groups and molecular structures based on their interaction with infrared light.

Mid-Infrared (MIR) Spectroscopy probes the fundamental vibrational transitions of molecules within the range of 4000–400 cm⁻¹. Absorption bands in this region provide a "fingerprint" for specific functional groups, with two primary regions of interest [35] [36]:

- Functional Group Region (4000–1500 cm⁻¹): This area reveals stretches of key bonds, notably O-H and N-H around 3400-3200 cm⁻¹ (broad, "tongue"-like peaks), and C=O around 1750-1650 cm⁻¹ (sharp, "sword"-like peaks) [35].

- Fingerprint Region (1500–500 cm⁻¹): This region contains complex patterns from bending and skeletal vibrations, which are unique to entire molecules and are crucial for definitive identification [36].

Near-Infrared (NIR) Spectroscopy covers the range of 12,500–3800 cm⁻¹ (800–2500 nm). This region consists of overtones and combination bands of the fundamental vibrations seen in the MIR, primarily involving C-H, N-H, and O-H bonds [37]. While bands are broader and more overlapping, the technique is exceptionally suited for the rapid, non-destructive quantitative analysis of organic constituents through chemometric modeling [38] [37].

Experimental Protocols

Safety and Sample Handling Protocol

Disclaimer: The handling and analysis of explosives and precursors are extremely hazardous and must only be performed by trained personnel in appropriate secure and controlled environments, using all necessary personal protective equipment (PPE).

- Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Wear lab coat, safety glasses, face shield, and flame-retardant gloves.

- Sample Containment: Analyze samples through transparent containers (e.g., glass vials) whenever possible to minimize handling. Raman spectroscopy is particularly suited for this as it can analyze samples through containers [1].

- Sample Quantity: Use sub-milligram quantities for initial tests to mitigate risk.

- Laser Safety: When using Raman spectrometers, be aware that dark-colored or sensitive explosives (e.g., black powder, TATP) can absorb laser energy and ignite, especially with continuous-wave lasers [33]. A pulsed laser system can significantly reduce this risk [33].

Protocol 1: FT-IR Analysis of Solid HMEs and Precursors (ATR Method)

This protocol is ideal for identifying functional groups in solid materials, such as explosive precursors or post-blast residues [34].

- Objective: To identify characteristic functional groups in a solid unknown sample.

- Materials:

- FT-IR spectrometer with Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR) accessory.

- Solid unknown sample (e.g., powder, crystal).

- Fine-tipped spatula.

- Methanol for cleaning.

- Procedure:

- Clean the ATR crystal thoroughly with methanol and allow it to dry. Acquire a background spectrum with no sample present.

- Place a small amount of the solid sample onto the ATR crystal.

- Apply uniform pressure to the sample using the instrument's anvil to ensure good contact with the crystal.

- Acquire the IR spectrum (typically 16-32 scans at 4-8 cm⁻¹ resolution).

- Clean the crystal thoroughly after use.

- Data Interpretation: Compare the acquired spectrum to reference libraries. Key regions to inspect are summarized in Table 1.

Protocol 2: In-line NIR Monitoring for Process Analysis

This protocol demonstrates the application of NIR for quantitative monitoring, exemplified in a hot-melt extrusion (HME) process, which is analogous to continuous mixing processes that could be misused for HME production [38].

- Objective: To quantitatively monitor the concentration of an Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) and a surfactant in a hot-melt extrusion process in real-time.

- Materials:

- FT-NIR spectrometer (e.g., Thermo Antaris II) with transmission probes.

- In-line, temperature-controlled die adapter with a fixed optical pathlength.

- Twin-screw extruder.

- PAT software (e.g., Siemens SIPAT) for data management and modeling.

- Procedure:

- Integrate the NIR transmission probe into the process stream via the die adapter.

- Set spectral acquisition parameters: range of 4000–10,000 cm⁻¹, resolution of 16 cm⁻¹, 16 co-added scans.

- Manufacture calibration samples with varying levels of API (e.g., 0–30%) and surfactant (e.g., 5–27%).

- Use Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression to build a quantitative model correlating spectral data to reference HPLC measurements.

- Apply pre-processing techniques (e.g., Savitzky-Golay derivative, Standard Normal Variate (SNV) correction) to the spectral data to improve model performance [38] [37].

- Deploy the model for real-time prediction and release of the intermediate product.

- Data Interpretation: The PLS model provides real-time predictions of component concentrations, allowing for process control and fault detection.

Protocol 3: Detection of H₂O₂-Based HMEs with Grocery Powders

This protocol uses GC-MS as a confirmatory technique following a presumptive IR identification of H₂O₂-based mixtures, which are difficult to identify by IR alone [34].

- Objective: To identify molecular markers of H₂O₂ oxidation in powdered groceries (e.g., coffee, tea, spices) for forensic attribution.

- Materials:

- Powdered groceries (coffee, black tea, paprika, turmeric).

- Concentrated hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) solution.

- Gas Chromatograph-Mass Spectrometer (GC-MS).

- Methanol, for extraction.

- Procedure: