Feature Augmentation in Forensic Text Detection: Advanced Methods for AI-Generated Content and Authorship Analysis

This article provides a comprehensive examination of feature augmentation techniques for modern forensic text detection systems.

Feature Augmentation in Forensic Text Detection: Advanced Methods for AI-Generated Content and Authorship Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of feature augmentation techniques for modern forensic text detection systems. Aimed at researchers and forensic professionals, it explores the foundational principles of detecting AI-generated content, plagiarism, and authorship changes. The scope spans from methodological applications of natural language processing (NLP) and machine learning to optimization strategies for handling adversarial attacks and data limitations. Through validation frameworks and comparative analysis of detection tools, this work synthesizes current trends and future directions for developing robust, generalizable forensic text analysis systems capable of addressing evolving challenges in digital content authentication.

The Forensic Text Detection Landscape: Core Concepts and Emerging Challenges

Defining Feature Augmentation in Text Forensics

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is feature augmentation in the context of text forensics? Feature augmentation in text forensics involves generating new or enhanced linguistic features from existing text data to improve the performance of machine learning models. It aims to create a more robust feature set that helps in identifying deceptive patterns, emotional cues, and other forensic indicators by making models less sensitive to specific word choices and more focused on underlying psycholinguistic patterns [1] [2].

2. How does feature augmentation improve forensic text detection models? It acts as a regularization strategy, preventing overfitting by encouraging models to learn generalizable abstractions rather than memorizing high-frequency patterns or spurious correlations in the training data. This leads to better performance on unseen forensic text data [2].

3. My model is overfitting to the training data. Which augmentation strategy should I try first? Synonym replacement via word embeddings is a highly effective starting point. This method preserves the original meaning and context while varying the lexical surface structure. For instance, you can use contextual embeddings from models like BERT to replace words with their context-aware synonyms [1].

4. What is the most common mistake when applying data augmentation? The most common mistake is validating the model's performance using the augmented data, which leads to over-optimistic and inaccurate results. Always use a pristine, non-augmented validation set. Furthermore, when performing K-fold cross-validation, the original sample and its augmented counterparts must be kept in the same fold to prevent data leakage [1].

5. Can I combine multiple augmentation methods? Yes, a mix of methods such as combining synonym replacement with random deletion or insertion can be beneficial. However, it is crucial not to over-augment, as this can distort the original meaning and degrade model performance. Experimentation is needed to find the optimal combination [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Model Accuracy After Augmentation

Symptoms

- Decreased accuracy on the test set.

- Increased loss during validation.

Possible Causes and Solutions

- Cause 1: Excessive Augmentation Strength. The augmentation has altered the text to the point where the original semantic meaning is lost.

- Solution: Reduce the augmentation parameters. For example, in synonym replacement, lower the percentage

pof words replaced. In random deletion, decrease the probabilitypof word removal [1].

- Solution: Reduce the augmentation parameters. For example, in synonym replacement, lower the percentage

- Cause 2: Inappropriate Augmentation Method. The chosen method may not be label-preserving for your specific forensic task.

- Cause 3: Data Leakage. The model is being validated on augmented data, giving a false sense of performance.

- Solution: Re-split your dataset, ensuring the validation set contains only original, non-augmented text [1].

Problem: Limited Improvement in Model Generalization

Symptoms

- High performance on training data but poor performance on unseen test data, even after augmentation.

Possible Causes and Solutions

- Cause 1: Lack of Diversity in Augmented Samples. The generated data lacks sufficient linguistic variety.

- Cause 2: Class Imbalance. The original dataset may have a severe class imbalance that augmentation has not adequately addressed.

- Solution: Apply augmentation strategically to the minority class only. Generate a higher number of synthetic samples for the under-represented class to balance the dataset [1].

Quantitative Data on Augmentation Techniques

The table below summarizes the performance impact of different data augmentation techniques on an NLP model for tweet classification, demonstrating how augmentation can improve model generalization [1].

Table 1: Impact of Data Augmentation on Model Performance (Tweet Classification)

| Augmentation Technique | Description | ROC AUC Score (Baseline: 0.775) | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| None (Baseline) | Original training data without augmentation. | 0.775 | Benchmark for comparison. |

| Synonym Replacement | Replacing n words with their contextual synonyms using word embeddings. |

0.785 | Preserves context effectively; optimal n is a key parameter. |

| Theoretical: Back-translation | Translating text to another language and back to the original. | Not Reported | Good for paraphrasing; quality depends on the translation API. |

| Theoretical: Random Deletion | Randomly removing words with probability p. |

Not Reported | Introduces noise; can help model avoid relying on single words. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing Synonym Replacement for a Forensic Text Classifier

This protocol outlines the steps to augment a dataset of suspect statements or messages using contextual synonym replacement to improve a deception detection model [1].

1. Objective: To increase the size and diversity of a text corpus for training a robust forensic classification model.

2. Materials:

* A labeled dataset of text samples (e.g., transcribed interviews, messages).

* Python programming environment.

* The nlpaug library.

3. Methodology:

* Step 1 - Data Preparation: Split the original dataset into training and validation sets. Crucially, the validation set must remain non-augmented [1].

* Step 2 - Augmenter Initialization: Initialize a contextual word embeddings augmenter within nlpaug.

Protocol 2: A Psycholinguistic Feature Augmentation Framework for Suspect Identification

This protocol is based on research that uses advanced NLP techniques to augment analytical features for identifying persons of interest from their language use [4] [5].

1. Objective: To augment a suspect's text with derived psycholinguistic features (deception, emotion) to identify key investigative leads.

2. Materials:

* A corpus of text from multiple suspects (e.g., transcribed police interviews).

* NLP libraries (e.g., Empath for deception analysis, NLTK, Scikit-learn).

* Feature calculation and correlation analysis tools.

3. Methodology:

* Step 1 - Feature Extraction: For each suspect's text, extract and calculate time-series data for:

* Deception: Using a library like Empath to identify and count words related to deception [4] [5].

* Emotion: Quantify levels of anger, fear, and neutrality over the course of the narrative [4] [5].

* Subjectivity: Measure the degree of subjective versus objective language [4] [5].

* Step 2 - N-gram Correlation: Extract n-grams (e.g., "that night", "at the park") from the text and calculate their correlation with investigative keywords and phrases related to the crime [4].

* Step 3 - Feature Augmentation & Synthesis: The calculated time-series and correlation metrics serve as augmented features. These engineered features provide a multidimensional psycholinguistic profile beyond the raw text.

* Step 4 - Suspect Ranking: Analyze the augmented feature set to identify suspects with profiles highly correlated to the crime. This includes high deception scores, specific emotional patterns, and strong n-gram correlations with the event [4] [5].

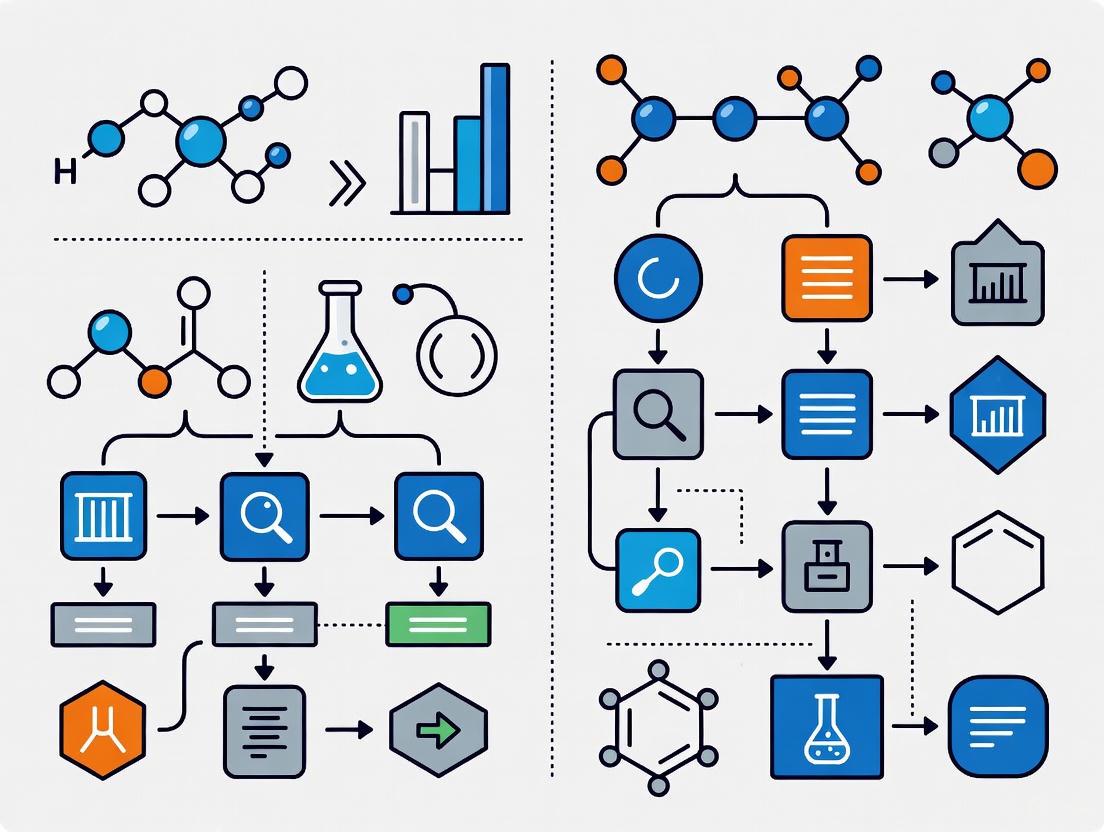

Workflow Visualization

Psycholinguistic Feature Augmentation Workflow

NLP Data Augmentation Decision Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools and Libraries for Feature Augmentation in Text Forensics

| Item Name | Function / Application | Relevant Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| NLPAug | A comprehensive Python library for augmenting NLP data at character, word, and sentence levels. Supports both contextual (BERT) and non-contextual (Word2Vec) embeddings. | Protocol 1 |

| Empath | A Python library used to analyze text against lexical categories, enabling the calculation of deception levels and other psychological cues over time. | Protocol 2 |

| Transformer Models (BERT, RoBERTa) | Provide state-of-the-art contextual embeddings for understanding and generating text. Used for high-quality synonym replacement and feature extraction. | Protocol 1, 2 |

| NLTK / SpaCy | Standard NLP libraries for essential preprocessing tasks (tokenization, lemmatization) and grammatical analysis. | Protocol 1, 2 |

| Scikit-learn | A machine learning library used for building the final classification or clustering models using the augmented features. | Protocol 1, 2 |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Our lab's AI-text detector shows a high false positive rate on scientific manuscripts. What could be the cause? A high false positive rate often stems from a concept known as "feature domain mismatch." Your detector was likely trained on general web text, not the specific linguistic and statistical features of scientific literature [6]. This mismatch causes it to flag formal, structured academic writing as AI-generated. To troubleshoot, retrain your classifier on a curated dataset of human-authored scientific papers from your field and their AI-generated counterparts. Furthermore, review the model's decision boundaries; it may be overly reliant on features like sentence length or paragraph structure, which are poor indicators in scientific writing [7].

Q2: Why does our forensic detection model fail to identify text from the latest LLMs like GPT-4? This is a problem of model generalization. Detection models often experience significant performance degradation when faced with text from a newer or more advanced generator than what was in their training data [7] [8]. This is because newer LLMs produce text with statistical signatures and perplexity profiles that are increasingly human-like. The solution involves implementing a continuous learning pipeline that regularly incorporates outputs from the latest LLMs into your training dataset. Augmenting your approach with model-based features, such as the probability curvature of the text, can also improve robustness against evolving generators [8].

Q3: How can we reliably detect AI-generated text that has been paraphrased to evade detection? Paraphrasing is a known adversarial attack that can degrade the performance of many detectors [8]. Relying on a single detection method is insufficient. You should adopt a multi-feature fusion strategy.

- Enhance your feature set: Move beyond simple statistical features. Integrate semantic embeddings from models like BERT to understand if the underlying ideas are coherent in a way characteristic of LLMs, even if the surface-level words have changed [7].

- Implement ensemble methods: Combine the outputs of multiple detectors, including those based on linguistic style, semantic coherence, and external LLM-based classifiers [8]. A consensus approach can be more resilient to manipulation.

- Explore watermarking: For internally generated text, advocate for the use of LLMs that incorporate robust, imperceptible watermarks, which can survive paraphrasing attacks [7] [8].

Q4: What is the most critical step in building an effective feature-augmented forensic text detector? The most critical step is the creation of a high-quality, balanced, and domain-relevant benchmark dataset [7] [9]. The performance of your entire detection framework is bounded by the data it learns from. This dataset must include:

- A substantial volume of human-authored text from your target domain (e.g., drug development research papers).

- A comparable volume of AI-generated text created from multiple LLMs (e.g., ChatGPT, Gemini, Copilot) and tailored to the same domain [9].

- Careful labeling and, if possible, augmentation to ensure the model learns robust features rather than dataset-specific artifacts [9].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Poor Generalizability to New Text Domains

Symptoms:

- The detector performs well on its original test set but poorly on text from new scientific disciplines.

- Accuracy drops significantly when processing text from non-English languages.

Diagnostic Steps:

- Perform Domain Shift Analysis: Compare the statistical characteristics (e.g., average word length, lexical diversity, sentence complexity) of your training data with the new domain. A significant divergence indicates a feature domain shift [6].

- Evaluate Feature Importance: Use model interpretation tools (e.g., SHAP) to identify which features are driving classifications. You may find the model is over-indexing on domain-specific jargon rather than general AI-generation cues.

Resolution Protocol:

- Apply Feature-Augmentation by Soft Domain Transfer: This technique harnesses intermediate layer representations from pre-trained neural models to create domain-invariant features. It allows knowledge from a resource-rich domain (e.g., general news) to improve performance in a resource-scarce domain (e.g., specialized medical literature) [6].

- Implement Multi-Domain Training: Actively expand your training corpus to include a diverse set of domains and languages. Data augmentation using Gen-AI tools can help generate synthetic training samples for underrepresented domains [9].

- Adopt a Hybrid CNN-BiLSTM Architecture: This architecture is particularly effective for generalization as it captures both local syntactic patterns (via CNN) and long-range semantic dependencies (via BiLSTM), making it less reliant on domain-specific stylistic rules [7].

Issue: Classifier Performance Degradation Over Time

Symptoms:

- Gradual decrease in detection accuracy and F1-score.

- Increase in false negatives as new, more capable LLMs are released.

Diagnostic Steps:

- Model Drift Detection: Continuously monitor the performance of your detector on a held-out validation set that is periodically updated with samples from the latest LLMs. A steady decline indicates model drift.

- Adversarial Robustness Testing: Systematically test your detector against paraphrased text, text with injected noise, and outputs from newly published model checkpoints [8].

Resolution Protocol:

- Establish a Continuous Learning Framework: Create an automated pipeline that periodically queries the latest LLMs using a fixed set of prompts, generates new training data, and fine-tunes your detection model. This is essential for keeping pace with the rapid evolution of generative AI [9] [8].

- Incorporate "Human-in-the-Loop" Verification: For borderline cases, integrate a manual review step. The decisions of human experts can be fed back into the system as new labeled data to reinforce correct learning [8].

- Shift to a Retrieval-Based Detection Paradigm: Instead of a pure classifier, consider a system that checks if a given text passage is too similar to content that could be generated by a known LLM. This method can be more adaptable to new models without requiring full retraining [8].

Experimental Data & Protocols

Table 1: Performance Comparison of AI-Text Detection Models

This table summarizes the quantitative performance of various detection approaches as reported in the literature, highlighting the effectiveness of hybrid and feature-augmented models. [7]

| Model / Framework | Accuracy (%) | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1-Score (%) | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proposed Hybrid CNN-BiLSTM | 95.4 | 94.8 | 94.1 | 96.7 | BERT embeddings, Text-CNN, Statistical features |

| RoBERTa Baseline | ~90* | ~89* | ~91* | ~90* | Transformer-based fine-tuning |

| DistilBERT Baseline | ~87* | ~85* | ~86* | ~85* | Lightweight transformer |

| Zero-Shot LLM Prompting | Moderate | Varies | Varies | Moderate | No training, prompt-based |

| Gen-AI Augmented Dataset | ~10% Increase | Improvement | Improvement | Improvement | Expands dataset from 1,079 to 7,982 texts [9] |

Note: Baseline values are approximated from the context of [7].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Forensic Text Detection

This table lists key digital "reagents" – software tools and datasets – essential for building and testing feature-augmentation forensic text detection systems. [7] [9] [8]

| Reagent Name | Type | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| BERT / sBERT | Model / Embedding | Generates deep contextual semantic embeddings for text, used as input features for classifiers [7] [9]. |

| Text-CNN | Feature Extractor | A convolutional neural network that extracts local, n-gram style syntactic patterns from text [7]. |

| BiLSTM Layer | Neural Network Component | Captures long-range dependencies and contextual flow in text, modeling sequential information [7]. |

| Turnitin / iThenticate | Software Service | Commercial plagiarism and AI-detection tool used for benchmarking and initial screening [10]. |

| CoAID / Custom Benchmarks | Dataset | Public and proprietary datasets used for training and evaluating the generalizability of detection models [7]. |

| OpenAI ChatGPT / Google Gemini | Generative AI | Used for data augmentation to create synthetic AI-generated text for training detectors [9]. |

Experimental Workflow Visualizations

Forensic Text Detection Workflow

Feature Augmentation by Domain Transfer

Continuous Learning for AI Detection

Forensic text detection systems have evolved into a multi-faceted scientific discipline focused on three core pillars: Detection (identifying AI-generated content), Attribution (determining the specific AI model involved), and Characterization (understanding the underlying intent of the text) [11]. This technical support center provides researchers and scientists with the experimental protocols and troubleshooting knowledge necessary to advance this critical field, with a specific focus on feature-augmented forensic systems.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental difference between plagiarism detection and AI-generated content detection?

Plagiarism detection identifies text copied from existing human-written sources, while AI-generated content detection distinguishes between human-authored and machine-generated text, even if the machine-generated text is entirely original [12]. The former looks for duplication, the latter for statistical and stylistic patterns indicative of AI models.

FAQ 2: How accurate are current AI detection tools, and what is the most critical metric for research settings?

Accuracy varies significantly between tools. However, for academic and research applications, the false positive rate (incorrectly flagging human-written text as AI-generated) is the most critical metric due to the severe consequences of false accusations [13]. While some mainstream tools can identify purely AI-generated text with high accuracy, their performance drops significantly when the text has been paraphrased or edited [13] [14].

FAQ 3: Can AI-generated content pass modern, "authentic" assessments?

Yes. Multiple studies have found that generative AI can produce content for "authentic assessments" that passes the scrutiny of experienced academics. AI tools are increasingly capable of long-form writing and complex tasks, with some models employing multi-step strategies that make their output highly convincing [13].

FAQ 4: What are the main technical approaches to AI-generated text detection?

The two primary approaches are watermarking (embedding a detectable pattern during text generation) and post-hoc detection (analyzing text after it is generated). Post-hoc detection can be further divided into supervised methods (trained on labeled datasets) and zero-shot methods [11]. Feature-augmented detectors often incorporate stylometric, structural, and sequence-based features to improve performance [11].

FAQ 5: Why might a detection tool misclassify human-written text?

Misclassification can occur with text written by non-native English speakers, highly formal prose, or technical scientific writing. This is often due to biases in the training data, which may over-represent certain writing styles [14]. Furthermore, edited or "humanized" AI content can significantly reduce detection performance [14].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Challenge 1: High False Positive Rates in Your Dataset

- Problem: Your detection model is flagging an unacceptable amount of human-written text as AI-generated.

- Solution:

- Re-evaluate Your Training Data: Ensure your human-text dataset is diverse and representative of the target domain (e.g., scientific manuscripts). Incorporate texts from non-native speakers and various stylistic formats [14].

- Prioritize Specificity: Adjust your classification threshold to favor specificity over sensitivity. A tool with a lower false positive rate is more suitable for high-stakes research environments [13].

- Benchmark Against Established Tools: Compare your model's outputs against mainstream tools known for low false positive rates, such as Turnitin, to identify potential biases in your system [13].

Challenge 2: Detecting Paraphrased or "AI-Humanized" Content

- Problem: Adversarial edits and paraphrasing tools are easily circumventing your detection system.

- Solution:

- Incorporate Robust Feature Sets: Move beyond basic classifiers. Augment your model with features that are harder to obscure through paraphrasing, such as:

- Stylometry: Analyze phraseology, punctuation, and linguistic diversity [11].

- Structural Features: Model the factual structure and contextual flow of the text [11].

- Sequence-based Features: Leverage information-theoretic principles like Uniform Information Density (UID) to quantify the smoothness of token distribution [11].

- Train on Hybrid Data: Include datasets that contain mixtures of AI-generated and human-edited text to make your model robust to these evasions [14].

- Incorporate Robust Feature Sets: Move beyond basic classifiers. Augment your model with features that are harder to obscure through paraphrasing, such as:

Challenge 3: Generalizing to New or Unseen AI Models

- Problem: Your detector performs well on text from known AI models (e.g., GPT-4) but fails on outputs from newer or open-source models.

- Solution: Focus on developing transferable detection methodologies. This involves using domain-invariant training strategies and feature sets that capture the fundamental differences between human and machine text, regardless of the specific model architecture [11].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol: Evaluating AI Detection Tool Performance

Aim: To quantitatively assess the performance of AI content detection tools on a specific corpus of scientific text.

Materials:

- Corpus of human-written scientific abstracts (e.g., from PubMed).

- Corpus of AI-generated scientific abstracts (created using prompts based on the human abstract topics).

- Access to selected AI detection tools (e.g., via API or web interface).

- Statistical analysis software (e.g., R, Python).

Methodology:

- Dataset Curation: Create a balanced, labeled dataset of human and AI-generated text samples. Ensure the AI-generated samples are produced with varying levels of prompting sophistication.

- Tool Selection: Select a range of detectors, including mainstream paid tools and newer entrants.

- Blinded Analysis: Submit each text sample to the detection tools in a blinded fashion, recording the score or classification provided.

- Data Collection: Record the following metrics for each tool:

- True Positives (TP), False Positives (FP), True Negatives (TN), False Negatives (FN).

- Statistical Analysis: Calculate key performance indicators:

- Accuracy: (TP+TN) / (TP+TN+FP+FN)

- Precision: TP / (TP+FP)

- Recall/Sensitivity: TP / (TP+FN)

- Specificity: TN / (TN+FP)

- F1-Score: 2 * (Precision * Recall) / (Precision + Recall)

Troubleshooting: If false positive rates are unacceptably high (>5%), re-run the experiment focusing on the tool's "human" score and adjust the classification threshold accordingly [13].

Protocol: Feature Augmentation for Improved Detection

Aim: To enhance a baseline detector by incorporating stylometric and structural features.

Materials:

- Baseline pre-trained language model (PLM) classifier (e.g., based on RoBERTa).

- Feature extraction libraries (e.g., for linguistic diversity, syntax trees).

- Labeled dataset of human and AI-generated text.

Methodology:

- Baseline Establishment: Run the baseline PLM classifier on your test dataset and record performance metrics.

- Feature Extraction: For each text sample, extract a set of augmenting features. Refer to the table below for key feature categories.

- Feature Fusion: Combine the feature vectors from the PLM with the newly extracted stylometric/structural features.

- Model Training & Evaluation: Train a new classifier (e.g., a neural network ensemble) on the fused feature set. Compare its performance against the baseline model using the same test dataset and metrics.

Feature Augmentation Workflow for Forensic Text Detection

Performance of Selected AI Detection Tools

Table 1: Accuracy of tools in identifying purely AI-generated text. Note: Performance is highly dependent on text origin and detector version, so these figures are indicative rather than absolute [13].

| Detection Tool | Kar et al. (2024) Accuracy | Lui et al. (2024) Accuracy | Perkins et al. (2024) Accuracy | Weber-Wulff (2023) Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Copyleaks | 100% | - | 64.8% | - |

| Turnitin | 94% | - | 61% | 76% |

| GPTZero | 97% | 70% | 26.3% | 54% |

| Originality.ai | 100% | - | - | - |

| Crossplag | - | - | 60.8% | 69% |

| ZeroGPT | 95.03% | 96% | 46.1% | 59% |

Table 2: Key performance metrics to calculate during tool evaluation, based on the experimental protocol in Section 4.1.

| Metric | Formula | Interpretation in Research Context |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | (TP+TN) / Total | Overall correctness, but can be misleading with imbalanced data. |

| Precision | TP / (TP+FP) | The proportion of flagged texts that are truly AI-generated. High precision is critical to avoid false accusations. |

| Recall | TP / (TP+FN) | The tool's ability to find all AI-generated texts. High recall is needed for comprehensive screening. |

| F1-Score | 2(PrecisionRecall)/(Precision+Recall) | The harmonic mean of precision and recall; a single balanced metric. |

| False Positive Rate | FP / (FP+TN) | The rate of misclassifying human text as AI. The most critical metric for academic integrity contexts [13]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Essential components for building and testing feature-augmented forensic text detection systems.

| Tool / Material | Function / Rationale | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-trained Language Models (PLMs) | Serve as powerful baseline classifiers for text sequence analysis. | RoBERTa, BERT, DeBERTa. Fine-tuned versions (e.g., GPT-2 detector) are common starting points [11]. |

| Stylometry Feature Extractors | Quantify nuances in writing style to distinguish between human and AI authors. | Libraries to analyze punctuation density, syntactic patterns, lexical diversity, and readability scores [11]. |

| Structural Analysis Libraries | Model the organization and factual flow of text, which can differ between humans and AI. | Tools for parsing syntax trees, analyzing discourse structure, and modeling entity coherence [11]. |

| Benchmark Datasets | Provide standardized, labeled data for training and fair comparison of detection models. | Include both public datasets (e.g., HC3) and custom, domain-specific corpora (e.g., scientific abstracts). |

| Adversarial Training Data | Improves model robustness against evasion techniques like paraphrasing and word substitution. | Datasets containing AI-text that has been processed by paraphrasing tools or manually edited [14]. |

| Sequence Analysis Tools | Implement information-theoretic measures to detect the "smoothness" characteristic of AI text. | Calculate metrics like perplexity, burstiness, and Uniform Information Density (UID) [11] [14]. |

Current Trends in Natural Language Processing for Forensic Analysis

FAQs: Feature Augmentation for Forensic Text Detection

1. What is feature augmentation, and why is it critical for forensic text detection?

Feature augmentation enhances forensic text detection systems by integrating multiple types of linguistic and statistical features beyond basic text classification. This approach improves the system's ability to distinguish between human-written and AI-generated text, especially as Large Language Models (LLMs) become more sophisticated. Augmenting standard models with stylometric, structural, and psycholinguistic features helps capture subtle nuances in writing style, making detectors more robust and transferable across different AI models [11].

2. My detection model performs well on training data but generalizes poorly to new LLMs. What feature augmentation strategies can improve transferability?

This is a common challenge due to the rapid evolution of LLMs. To enhance transferability:

- Integrate Stylometry Features: Augment your model with features that capture an author's unique stylistic choices, such as phraseology, punctuation patterns, and linguistic diversity. These features are often less model-specific and can improve detection of AI-generated tweets and other content [11].

- Use Domain-Invariant Training: Employ training strategies that force the model to learn features that are generalizable across different AI generators, rather than overfitting to the characteristics of a specific model in your training set [11].

3. How can psycholinguistic features be leveraged to identify deception or suspicious entities in forensic text analysis?

Psycholinguistic features help bridge the gap between language and psychological states, which is valuable for forensic analysis.

- Analyze Deception and Emotion Over Time: Use libraries like Empath to calculate deception levels in text. Track emotions like anger, fear, and neutrality over time, as shifts in these can be indicative of deceptive behavior or heightened stress [4] [5].

- Correlate with Investigative Keywords: Identify key entities or suspects by measuring the correlation of their language (e.g., in emails or transcribed interviews) with specific investigative keywords and phrases related to the case. This can help narrow down a pool of candidates [4] [5].

4. What are the primary limitations of current AI-generated text detectors, and how can feature augmentation mitigate them?

The main limitations include:

- Dependence on Training Data: Supervised detectors can struggle with new AI models not represented in their training data [11].

- Evolving AI Sophistication: As LLMs better mimic human writing, the distinguishing features become subtler [11].

- Bias and Incomplete Outputs: LLMs and detectors can inherit biases from their training data [15]. Feature augmentation mitigates these issues by providing a richer, multi-faceted feature set that is harder for new AI models to replicate perfectly. Combining stylistic, structural, and psycholinguistic signals creates a more robust profile of AI-generated content [11] [4].

5. In a forensic investigation, how can I process text from encrypted or privacy-focused platforms?

The shift to secure cloud services presents a challenge. Modern digital forensics tools can sometimes simulate app clients to download user data from servers of applications like Telegram or Facebook using their APIs. By providing valid user account credentials (e.g., through a legal process), investigators can access and decrypt this data, as the server perceives the activity as user-initiated [15].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Accuracy in Detecting AI-Generated News Articles

Possible Cause & Solution:

- Cause: The model may rely on basic text features that are insufficient for detecting high-quality, persuasive AI-generated news.

- Solution: Augment the feature set with journalism-standard features. Evaluate the text's compliance with standards like the Associated Press Stylebook. AI-generated news often deviates from these professional writing conventions, providing a strong signal for detection [11].

Problem: Model Fails to Differentiate Between Human and AI-Generated Social Media Posts

Possible Cause & Solution:

- Cause: The model may not be capturing the unique structural and contextual patterns of short-form social media content.

- Solution: Implement a multi-branch network architecture like TriFuseNet. This network explicitly models stylistic, contextual, and other features simultaneously, augmenting the model's capability to detect AI-generated tweets and posts by providing a more comprehensive view of the text [11].

Problem: Inability to Identify "Authorship" of AI-Generated Text (Model Attribution)

Possible Cause & Solution:

- Cause: Standard detection models are designed for a binary human/AI classification and lack the features to distinguish between different source LLMs (e.g., GPT-4 vs. Llama).

- Solution: Focus on attribution as a separate pillar of the forensic system. Develop features and models specifically designed to trace text back to a source model. This goes beyond detection and is crucial for understanding the origin of AI-generated misinformation or propaganda [11].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Augmenting a Detector with Stylometric and Structural Features

This protocol outlines the methodology for enhancing a base text classifier.

1. Hypothesis: Augmenting a pre-trained language model (PLM) with stylometric and structural features will improve its accuracy and robustness in detecting AI-generated text.

2. Materials/Reagents: Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item Name | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Pre-trained Language Model (e.g., RoBERTa, BERT) | Serves as the base feature extractor for deep contextual text understanding. |

| Labeled Dataset (Human & AI-generated texts) | Provides ground truth for training and evaluating the supervised detector. |

| Stylometry Feature Extractor | Calculates features like punctuation density, syntactic complexity, and lexical diversity. |

| Structural Analysis Module (e.g., Attentive-BiLSTM) | Models relationships between sentences and long-range text structure. |

3. Methodology:

- Step 1: Data Preparation. Compile a dataset with texts labeled as "Human" or "AI-generated." Ensure the AI texts are generated from a variety of LLMs to test generalizability.

- Step 2: Feature Extraction.

- Extract deep contextual features using the final hidden layers of the PLM.

- Run the text through a stylometry module to get statistical features (e.g., average sentence length, unique word ratio).

- Use a structural module (like replacing the classifier's feed-forward layer with an Attentive-BiLSTM) to learn robust, interpretable features from the text sequence [11].

- Step 3: Feature Fusion. Combine the PLM features, stylometry features, and structural features into a single, augmented feature vector.

- Step 4: Classification & Evaluation. Train a classifier (e.g., SVM, Multi-layer Perceptron) on the augmented features. Evaluate performance on a held-out test set using metrics like accuracy, F1-score, and area under the ROC curve (AUC). Compare against a baseline model that uses only PLM features.

The workflow for this experimental protocol is as follows:

Protocol 2: Psycholinguistic Analysis for Suspect Prioritization

This protocol uses NLP to analyze text for deception and emotional cues.

1. Hypothesis: Measuring deception, emotion, and subjectivity over time in suspect narratives can help identify and prioritize key persons of interest in an investigation.

2. Materials/Reagents: Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Psycholinguistic Analysis

| Item Name | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Text Corpus (e.g., interview transcripts, emails) | The primary data for analysis, containing text from multiple suspects. |

| NLP Library (e.g., SpaCy, NLTK) | Provides tools for tokenization, part-of-speech tagging, and dependency parsing. |

| Emotion/Deception Library (e.g., Empath, LIWC) | Quantifies emotional tone, subjectivity, and potential deceptive cues in text. |

| Topic Modeling Algorithm (e.g., LDA) | Identifies latent topics within the text corpus to find thematic correlations. |

3. Methodology:

- Step 1: Data Collection & Preprocessing. Gather text data from all subjects (e.g., transcribed police interviews). Clean and standardize the text.

- Step 2: Temporal Psycholinguistic Analysis.

- Segment each subject's text into temporal chunks (e.g., by question in an interview).

- For each segment, calculate metrics for deception (using a library like Empath), emotion (anger, fear, neutrality), and subjectivity [4] [5].

- Plot these metrics over time to identify subjects with anomalous patterns.

- Step 3: Keyword and Topic Correlation.

- Step 4: Entity Ranking. Rank the subjects (entities) based on a combined score of their psycholinguistic anomalies and their correlation to the investigative topics. This ranked list helps investigators prioritize resources.

The logical flow for this analysis is visualized below:

The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from the research literature on feature-enhanced forensic NLP systems.

Table: Performance of Feature-Augmented Forensic Text Detection Systems

| Feature Augmentation Type | Base Model/Context | Key Performance Finding | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stylometry & Journalism Features | PLM-based Classifier | Improved detection of AI-generated tweets and news articles by capturing nuanced stylistic variations. | [11] |

| Structural Features (Attentive-BiLSTM) | RoBERTa-based Classifier | Enhanced detection capabilities by learning interpretable and robust structural features from text. | [11] |

| Psycholinguistic Features (Deception, Emotion) | NLP Framework for Suspect Analysis | Successfully identified guilty parties in a fictional crime scenario by analyzing deception and emotion over time, creating a prioritized suspect list. | [4] [5] |

Performance and Adoption Context

The following tables summarize key quantitative data on AI model performance, global investment, and organizational adoption, providing essential context for the challenges in forensic detection.

Table 1: AI Model Performance on Demanding Benchmarks (2023-2024) [16]

| Benchmark | Description | Performance Increase (2023-2024) |

|---|---|---|

| MMMU | Tests massive multi-task understanding | 18.8 percentage points |

| GPQA | Challenging graduate-level Q&A | 48.9 percentage points |

| SWE-bench | Evaluates software engineering capabilities | 67.3 percentage points |

Table 2: Global AI Investment and Adoption (2023-2024) [16] [17]

| Metric | Figure | Context/Year |

|---|---|---|

| U.S. Private Investment | $109.1 Billion | 2024 |

| Generative AI Investment | $33.9 Billion | 2024 (18.7% increase from 2023) |

| Organizations Using AI | 78% | 2024 (up from 55% in 2023) |

| Organizations Scaling AI | ~33% | 2024 (Majority in piloting/experimentation) |

Troubleshooting Guide: Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: My detection model, trained on a specific generator, shows a significant performance drop when tested on a new model. What are the primary remediation strategies?

This is a classic case of model generalization failure, exacerbated by the rapid evolution of AI generators [11]. The performance drop occurs because your detector has overfitted to the specific artifacts of its training data.

- Recommended Protocol: Feature-Augmented Transferable Detection

- Objective: To build a detector that learns domain-invariant features, making it robust to new, unseen generators.

- Methodology:

- Feature Augmentation: Enhance your base classifier (e.g., a RoBERTa or BERT model) by incorporating stylometric features. These include [11]:

- Phraseology and Punctuation: Analyze writing style patterns.

- Linguistic Diversity: Measure vocabulary richness and sentence structure complexity.

- Journalism-Standard Features: Check compliance with style guides (e.g., Associated Press Stylebook).

- Information-Theoretic Features: Calculate metrics like Uniform Information Density (UID) to quantify the smoothness of token distribution, which often differs between human and AI text.

- Domain-Invariant Training: Train your augmented model on a diverse dataset containing outputs from multiple AI generators. The goal is to force the model to learn the core, abstract features of AI-generated text rather than memorizing artifacts from a single source.

- Feature Augmentation: Enhance your base classifier (e.g., a RoBERTa or BERT model) by incorporating stylometric features. These include [11]:

- Expected Outcome: A detector with higher robustness and improved cross-generator generalization, though it may trade off a small amount of peak accuracy on the original generator.

FAQ 2: I am dealing with a class-imbalanced dataset where human-written text samples far outnumber AI-generated ones. How can I improve my model's performance on the minority class?

Data imbalance is a common issue that biases models toward the majority class. The strategy is to artificially balance your training data.

- Recommended Protocol: Text Data Augmentation for Minority Class

- Objective: To increase the quantity and diversity of AI-generated training samples.

- Methodology: Apply one or both of the following techniques to your AI-generated text data [18]:

- Back Translation (BT):

- Translate the original AI-generated text (e.g., in Romanian) into an intermediate language (e.g., German).

- Translate the German text back into the original Romanian.

- Use this new, paraphrased text as an additional training sample. This preserves semantic meaning while altering syntactic structure.

- Easy Data Augmentation (EDA):

- Synonym Replacement: Replace n random non-stop words with their synonyms.

- Random Insertion: Insert a random synonym of a random word at a random position, repeated n times.

- Random Swap: Randomly swap the positions of two words in the sentence, repeated n times.

- Random Deletion: Randomly remove each word in the sentence with a probability p.

- Back Translation (BT):

- Expected Outcome: A more balanced dataset that reduces model bias, leading to improved recall for the AI-generated class and a higher overall F1 score.

FAQ 3: How can I move beyond simple binary detection to gain more forensic insights into the AI-generated text?

Advanced forensic analysis requires moving from detection to attribution and characterization [11].

- Recommended Protocol: Multi-Task Forensic Analysis

- Objective: To not only detect AI-generated text but also identify its source model (attribution) and its potential intent (characterization).

- Methodology:

- Attribution as Classification: Frame the attribution task as a multi-class classification problem. The labels are the set of known source models (e.g., GPT-4, Llama, Gemini). Train a model on a dataset where texts are labeled with their origin.

- Leverage Model Fingerprints: The hypothesis is that different LLMs leave distinct "fingerprints" in their outputs—structured patterns in their use of vocabulary, grammar, and style. Your feature-augmented detector should be trained to recognize these subtle, model-specific clues.

- Characterization via Intent Analysis: For intent characterization (e.g., detecting misinformation or propaganda), treat this as a separate classification or sequence-labeling task, potentially using the features extracted for detection and attribution as a starting point.

- Expected Outcome: A more comprehensive forensic system that can answer "Was this AI-generated?", "Which model generated it?", and "What was its likely purpose?".

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for AI-Generated Text Forensics Research

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Pre-trained Language Models (PLMs) | Base models (e.g., RoBERTa, DeBERTa) used as the foundation for building specialized detection classifiers [11]. |

| Benchmark Datasets (e.g., HFFD, FF++) | Large-scale, labeled collections of real and fake face images or text used for training and, more importantly, standardized evaluation and comparison of different detection methods [19]. |

| Stylometry Feature Extractors | Software tools or custom algorithms to quantify writing style, including readability scores, lexical diversity, n-gram stats, and punctuation density [11]. |

| Structured Feature Mining Framework (e.g., MSF) | A data augmentation framework designed to force CNN-based detectors to look at global, structured forgery clues in images (and conceptually adaptable to text) by dynamically erasing strong and weak correlation regions during training [19]. |

| AI Text Generators (for data synthesis) | A suite of various LLMs (e.g., GPT-4, Llama, Claude) used to create a diverse set of AI-generated text samples for training and adversarial testing of detectors [11]. |

Experimental Protocol: Feature-Augmented Detection

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for developing a robust, feature-augmented forensic text detection system.

Title: Developing a Transferable AI-Generated Text Detector via Stylometric Feature Augmentation.

Objective: To train a classifier that distinguishes human-written from AI-generated text with high accuracy and robust generalization across multiple AI text generators.

Materials & Datasets:

- Base Classifier: A pre-trained Transformer model like RoBERTa-base.

- Datasets: A mix of human-written texts (e.g., Wikipedia articles, news) and AI-generated texts from multiple models (e.g., GPT-3.5, GPT-4, Llama 2, Gemini). The dataset should be split into training, validation, and testing sets, with a portion of the AI-generated texts held back from training to test generalization.

- Feature Extraction Libraries: Libraries for calculating text statistics (e.g., textstat), NLP toolkits (e.g., spaCy, NLTK) for part-of-speech tagging and dependency parsing.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Data Collection and Preprocessing:

- Compile your dataset, ensuring it is balanced between human and AI-generated classes.

- Clean and tokenize all text samples.

- For the AI-generated portion, create a meta-dataset labeling which source model generated each text.

Feature Extraction:

- Deep Learning Features: Pass tokenized text through the RoBERTa model to obtain a [CLS] token embedding or mean pooling of the last hidden layer outputs. This will serve as your base feature vector.

- Stylometric Features: For each text sample, calculate a suite of hand-crafted features. This includes [11]:

- Lexical: Type-Token Ratio, average word length, sentence length variance.

- Syntactic: Frequency of certain part-of-speech tags, usage of passive voice.

- Readability: Flesch Reading Ease, Gunning Fog Index.

- Punctuation: Density of commas, semicolons, exclamation marks.

- Information-Theoretic Features: Calculate perplexity using a standard language model and derive Uniform Information Density (UID) measures [11].

Feature Fusion:

- Normalize all hand-crafted feature vectors to have zero mean and unit variance.

- Concatenate the normalized stylometric and information-theoretic feature vector with the deep learning feature vector from RoBERTa to create a fused, augmented feature representation.

Model Training and Validation:

- Add a classification head on top of the fused feature vector.

- Train the model on the training set, using the validation set for hyperparameter tuning and early stopping. Monitor for overfitting.

Evaluation and Generalization Testing:

- In-Distribution Test: Evaluate the final model on the standard test set containing texts from known generators.

- Out-of-Distribution (Generalization) Test: Evaluate the model on the held-back test set containing texts from unseen AI models. Compare the performance (Accuracy, F1-score) against a baseline model trained only on deep learning features.

System Visualization: Forensic Analysis Workflow

Advanced Protocol: Multi-Task Forensic System

This protocol expands on the previous one to include model attribution and intent characterization.

Title: Building a Multi-Task Forensic System for Detection, Attribution, and Characterization of AI-Generated Text.

Objective: To create a unified system that can detect AI-generated text, identify its source model, and classify its potential malicious intent (e.g., misinformation, propaganda).

Materials & Datasets:

- All materials from the previous protocol.

- Attribution Labels: Data must be labeled with the specific AI model that generated it (e.g., "GPT-4", "Llama 2 70B").

- Characterization Labels: A subset of the data (particularly AI-generated) must be labeled for intent (e.g., "Benign", "Misinformation", "Propaganda"). This may require expert annotation.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Follow Steps 1-3 from the "Feature-Augmented Detection" protocol to create a fused feature vector for each text sample.

Multi-Task Head Architecture:

- The fused feature vector is fed into three separate classification heads:

- Detection Head: A binary classifier (Human vs. AI).

- Attribution Head: A multi-class classifier (number of classes = number of known source models + 1 for "Human" or "Unknown").

- Characterization Head: A multi-class classifier for intent (number of classes = number of defined intent categories).

- The fused feature vector is fed into three separate classification heads:

Joint Training:

- The model is trained with a combined loss function, typically a weighted sum of the individual losses for each task (e.g., Cross-Entropy for detection, attribution, and characterization).

- This allows the shared feature extractor to learn representations that are useful for all three forensic tasks simultaneously.

Evaluation:

- Evaluate each task head independently on its respective metrics (e.g., F1 for detection, accuracy for attribution and characterization).

- Analyze the trade-offs between the tasks and how performance on one affects the others.

Implementing Feature Augmentation: Techniques and Workflows for Effective Detection

FAQ: Stylometric and Syntactic Analysis for Forensic Text Detection

Q1: What is the core difference between stylometric and syntactic analysis in forensic text detection?

Stylometric analysis is a quantitative methodology for authorship attribution that identifies unique, unconscious stylistic fingerprints in writing. It focuses on the statistical distribution of features like function words (the, and, of), punctuation patterns, and lexical diversity, which are largely independent of content [20] [21]. Syntactic analysis, a core component of Natural Language Processing (NLP), involves parsing text to understand its grammatical structure, conforming to formal grammar rules to draw out precise meaning and build data structures like parse trees [22] [23]. In forensic systems, stylometry helps answer "who wrote this?" by analyzing style, while syntactic analysis helps understand "how is this sentence constructed?" by analyzing grammar, with both serving as complementary features for detection models [11].

Q2: Why are function words so powerful for stylometric analysis in forensic detection?

Function words (e.g., articles, prepositions, conjunctions) are highly effective style markers because they are used in a largely unconscious manner by authors and are mostly independent of the topic of the text [24] [25]. This makes them a latent fingerprint that is difficult for a would-be forger to copy consistently. Stylometric methods like Burrows' Delta rely heavily on the frequencies of the most frequent words (MFW), which are predominantly function words, to measure stylistic similarity and attribute authorship [25] [21].

Q3: Our supervised detector for AI-generated text performs well on known LLMs but fails on new models. How can we improve its transferability?

This is a well-known challenge, as supervised detectors often overfit to the specific characteristics of the AI models in their training set [11]. To enhance transferability:

- Focus on Generalizable Features: Prioritize features that are fundamental to human language, such as those based on the Uniform Information Density (UID) hypothesis, which suggests humans distribute information more evenly than AI models [11]. Stylometric features like syntactic patterns and punctuation use have also shown good cross-model performance [26].

- Incorporate Domain-Invariant Training: Use machine learning strategies that explicitly train models to learn features invariant across different AI generators, preventing over-reliance on model-specific artifacts [11].

- Feature Augmentation: Augment your feature set with a wider array of stylometric and structural features to build a more robust model. Ensembles of stylometry features and pre-trained language model classifiers have been shown to bolster effectiveness [11].

Q4: What are the key limitations of using stylometry as evidence in forensic or legal contexts?

While powerful, stylometry currently faces hurdles for admissibility in legal proceedings. A primary limitation is the lack of a universally accepted, coherent probabilistic framework to assess the probative value of its results [27]. Conclusions are often presented as statistical probabilities rather than definitive proof. Furthermore, an author's style can vary over their career or be deliberately obfuscated through adversarial stylometry, potentially undermining the reliability of the analysis [21] [27]. Courts require validated methodologies with known error rates, a standard still being solidified for many stylometric techniques [27].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Low accuracy in distinguishing between human and advanced LLM (e.g., GPT-4) generated text.

- Potential Cause 1: Over-reliance on a single feature type (e.g., only using lexical diversity).

- Solution: Implement feature augmentation. Combine multiple feature types to create a more robust model. The table below summarizes key feature categories to consider [11] [26]:

- Potential Cause 2: The dataset is too small or lacks a balanced representation of human and AI-generated texts.

- Solution: Utilize existing benchmark datasets, such as the Beguš corpus of short stories, or create your own using a structured protocol with predefined prompts for both humans and LLMs [25]. Ensure your dataset is balanced and of sufficient size for statistical power.

Problem: Inconsistent results when performing syntactic analysis with a parser.

- Potential Cause: The grammar rules defined for the parser are not adequate for the complexity of the sentences in your corpus.

- Solution: Use a robust, pre-existing grammar framework like Context-Free Grammar (CFG) [22] [23]. For complex texts, leverage modern NLP libraries like NLTK in Python, which come with pre-trained parsers capable of handling a wide range of grammatical structures [23].

Problem: An author is deliberately trying to hide their writing style to fool the forensic system.

- Potential Cause: This is an instance of adversarial stylometry, where an individual alters their style to avoid detection [21].

- Solution: Research is ongoing, but potential solutions include developing detection methods that are sensitive to the practice of adversarial stylometry itself, as the obfuscation process may introduce new, detectable stylistic signals. Using a wider array of deeply ingrained, subconscious features (e.g., specific syntactic constructions) can also make style-masking more difficult [21].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol for Stylometric Analysis using Burrows' Delta

This protocol is adapted from studies comparing human and AI-generated creative writing [25].

Objective: To quantitatively measure stylistic differences between a set of texts and visualize their grouping.

Materials:

- A corpus of texts (e.g., the Beguš corpus, which contains human and LLM-generated short stories) [25].

- Natural Language Toolkit (NLTK) in Python.

- Scripts for calculating Burrows' Delta and performing clustering.

Methodology:

- Preprocessing: Clean the text data by converting to lowercase, removing non-alphanumeric characters, and optionally lemmatizing tokens.

- Feature Extraction: Identify the N Most Frequent Words (MFW) across the entire corpus. Typically, these will be function words.

- Frequency Normalization: Calculate the z-scores for the frequency of each MFW in each text. This standardizes the data.

- Calculate Delta: For each pair of texts, compute Burrows' Delta, which is the mean of the absolute differences between the z-scores of all MFW. A lower Delta indicates greater stylistic similarity.

- Clustering and Visualization: Apply hierarchical clustering with average linkage to the matrix of Delta values. Visualize the results using a dendrogram. Alternatively, use Multidimensional Scaling (MDS) to project the high-dimensional relationships into a 2D scatter plot.

The workflow for this analysis can be summarized as follows:

Protocol for Syntactic Analysis using Constituency Parsing

This protocol outlines the process of extracting a sentence's grammatical structure [23].

Objective: To generate a parse tree that represents the grammatical structure of a sentence.

Materials:

- A sample sentence (e.g., "This tree is illustrating the constituency relation").

- The NLTK Python module.

Methodology:

- Tokenization: Split the input sentence into individual words (tokens).

- Part-of-Speech (POS) Tagging: Assign a grammatical tag (e.g., Noun

NN, VerbVB, DeterminerDT) to each token. - Define a Grammar: Specify a set of phrase structure rules that define how words form phrases. Example:

NP: {<DT>?<JJ>*<NN>}# Noun Phrase: optional Determiner, any number of Adjectives, followed by a Noun.VP: {<VB.*> <NP|PP>*}# Verb Phrase: A verb followed by any number of Noun Phrases or Prepositional Phrases. - Parsing: Use a parser (e.g., NLTK's

RegexpParser) to apply the grammar rules to the POS-tagged sentence. - Output: Generate and visualize the constituency-based parse tree.

Table 1: Performance of Stylometric Classification (Human vs. AI-Generated Text)

| Model Type | Text Type | Classification Scenario | Performance Metric | Score | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tree-based (LightGBM) | Short Summaries | Binary (Wikipedia vs. GPT-4) | Accuracy | 0.98 | [26] |

| Tree-based (LightGBM) | Short Summaries | Multiclass (7 classes) | Matthews Correlation Coefficient | 0.87 | [26] |

Table 2: Key Stylometric Features for Discriminating Human and AI-Generated Text

| Feature Category | Example Features | Utility in Forensic Detection |

|---|---|---|

| Lexical | Word length, vocabulary richness, word frequency profiles (Zipf's Law) | Measures diversity and sophistication of vocabulary; AI text may be more uniform [25] [27]. |

| Syntactic | Sentence length, part-of-speech n-grams, grammar rules, phrase structure | Analyzes sentence complexity and structure; AI can show greater grammatical standardization [26]. |

| Structural | Punctuation frequency, paragraph length, presence of grammatical errors | Captures layout and formatting habits; humans may make more "casual" errors [11]. |

| Function Words | Frequency of "the", "and", "of", "in" (Burrows' Delta) | Acts as a latent, unconscious fingerprint of an author or AI model [25] [24]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software and Tools for Stylometric and Syntactic Analysis

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Language Toolkit (NLTK) | Python Library | Provides comprehensive modules for tokenization, POS tagging, parsing, and frequency distribution analysis. | [25] [24] [23] |

| Burrows' Delta | Algorithm/ Script | A foundational stylometric method for calculating stylistic distance between texts based on most frequent words. | [25] |

| Stylo (R package) | R Library | An open-source R package dedicated to a variety of stylometric analyses, including authorship attribution. | [21] |

| JGAAP | Software Platform | The Java Graphical Authorship Attribution Program provides a graphical interface for multiple stylometric algorithms. | [21] |

This technical support center assists researchers in implementing two advanced feature sets for forensic text detection: the NELA Toolkit, which provides hand-crafted content-based features, and RAIDAR, which utilizes rewriting-based features from Large Language Models (LLMs). These methodologies support feature augmentation approaches for detecting AI-generated text, a critical need in maintaining information integrity across scientific and public domains [11].

NELA Toolkit: Technical Support

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the main feature groups in the NELA toolkit and what do they measure? The NELA feature extractor computes six groups of text features normalized by article length [28]:

- Style: Captures writing style and structure via part-of-speech tags, quotes, punctuation, and capitalized words.

- Complexity: Measures writing complexity through lexical diversity, reading difficulty metrics, and word/sentence length.

- Bias: Identifies subjective language using counts of hedges, factives, assertives, implicatives, and opinion words.

- Affect: Quantifies sentiment and emotion using VADER sentiment analysis.

- Moral: Applies Moral Foundation Theory to assess moral reasoning in text.

- Event: Captures temporal and spatial context through counts of locations, dates, times, and time-related words.

Q2: How do I install the NELA features package and what are its dependencies?

Install using pip: pip install nela_features. The package automatically handles Python dependencies and required NLTK downloads. For research use only [28].

Q3: What is the proper way to extract features from a news article text string?

You can also extract feature groups independently: extract_style(), extract_complexity(), extract_bias(), extract_affect(), extract_moral(), and extract_event() [28].

Troubleshooting Guide

Problem: "LIWC dictionary not found" error

- Cause: Current NELA versions don't include LIWC features due to licensing.

- Solution: Contact Dr. James Pennebaker (pennebaker@utexas.edu) for LIWC dictionary access or purchase LIWC from official sources [28].

Problem: Inconsistent feature scaling across analyses

- Cause: NELA features are normalized by text length but aren't uniformly scaled.

- Solution: Apply standard scaling (Z-score normalization) to features before model training to ensure consistent performance [28].

Problem: Poor generalization to new domains

- Cause: Features were originally designed and validated on news content.

- Solution: For non-news domains (social media, academic text), perform domain adaptation with target-domain labeled data to recalibrate feature importance [29].

RAIDAR Rewriting Features: Technical Support

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the core principle behind RAIDAR's detection method? RAIDAR exploits the finding that LLMs tend to make fewer edits when rewriting AI-generated text compared to human-written text. This "invariance" property stems from LLMs perceiving their own output as high-quality, thus requiring minimal modification [30] [31].

Q2: What rewriting change measurements are most effective for detection?

- Bag-of-words edit score: Measures lexical changes while ignoring word order.

- Levenshtein distance: Quantifies character-level editing differences.

- Iterative rewriting distance: Computes edit distance between original and iteratively rewritten versions for enhanced signal [31].

Q3: How does prompt selection affect RAIDAR performance? Using multiple diverse prompts (typically 7) increases rewritten version diversity and detection robustness. Prompt variety should cover different rewriting styles (paraphrasing, formalization, simplification) to comprehensively capture invariance patterns [32].

Troubleshooting Guide

Problem: High computational cost and latency

- Cause: Multiple LLM rewriting calls required per text sample.

- Solution: Implement batch processing and consider smaller, distilled LLMs for rewriting. The L2R (Learn to Rewrite) fine-tuning framework can optimize smaller models specifically for this task [31].

Problem: Performance degradation against adversarial attacks

- Cause: Sophisticated paraphrasing attacks can reduce rewriting distance differences.

- Solution: Employ iterative rewriting and combine with NELA features for multi-perspective detection. The L2R training framework improves robustness through hard sample training [31].

Problem: Inconsistent results across domains

- Cause: Optimal edit distance thresholds vary by text type and domain.

- Solution: Implement domain-specific calibration or use machine learning classifiers (like XGBoost) instead of fixed thresholds to determine generation likelihood [29].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: NELA Feature Extraction and Classification

Purpose: Distinguish human-written from AI-generated text using content-based features [29].

Materials:

- Text corpus with human/AI labels

- nela_features Python package

- Classification library (XGBoost, Scikit-learn)

Methodology:

- Preprocessing: Clean text, remove extraneous formatting, handle encoding issues.

- Feature Extraction:

- Feature Scaling: Apply standard scaler to normalize all features.

- Model Training: Train XGBoost classifier with 70% data, using cross-validation for hyperparameter tuning.

- Evaluation: Test on held-out 30% dataset, reporting accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score.

Validation: Compare performance against baseline models using only lexicon-based features.

Protocol 2: RAIDAR Detection Implementation

Purpose: Leverage LLM rewriting invariance for AI-generated text detection [30] [32].

Materials:

- Access to LLM API (Llama-3.1-70B or equivalent)

- Text corpus with human/AI labels

- Edit distance calculation library

Methodology:

- Prompt Preparation: Prepare 7 diverse rewriting prompts (paraphrase, formalize, simplify, etc.).

- Rewriting Phase: For each text sample, generate 7 rewritten versions using the LLM with different prompts.

- Feature Calculation: For each rewritten version, compute:

- Bag-of-words edit score

- Normalized Levenshtein distance

- Sentence-level modification rate

- Classification: Use edit distance features to train classifier or apply threshold-based detection.

- Validation: Evaluate cross-domain performance and compare against commercial detectors.

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Solution | Function in Research | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| nela_features Python Package | Extracts 6 groups of linguistic features from text | Install via pip; requires NLTK; research use only [28] |

| LLM Rewriting Engine (e.g., Llama-3.1-70B) | Generates rewritten versions for RAIDAR analysis | API or local deployment; multiple prompts enhance diversity [32] |

| XGBoost Classifier | Integrates features for detection | Handles mixed feature types; provides feature importance scores [29] |

| LIWC Dictionary | Provides psycholinguistic features (separate from NELA) | Requires license purchase; contact Dr. Pennebaker [33] |

| Edit Distance Calculators | Quantifies text modifications in RAIDAR | Implement bag-of-words and Levenshtein distances for comprehensive analysis [31] |

Performance Data

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Feature Sets in AI-Generated Text Detection (F1 Scores)

| Domain | NELA Features Only | RAIDAR Features Only | Combined Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| News Articles | 0.89 | 0.82 | 0.90 |

| Academic Writing | 0.85 | 0.79 | 0.86 |

| Social Media | 0.81 | 0.76 | 0.83 |

| Creative Writing | 0.83 | 0.81 | 0.84 |

| Student Essays | 0.87 | 0.84 | 0.88 |

Table 2: NELA Feature Groups and Their Detection Effectiveness (Mean AUC Scores)

| Feature Group | Human vs. AI Detection | Model Attribution |

|---|---|---|

| Style | 0.81 | 0.75 |

| Complexity | 0.79 | 0.72 |

| Bias | 0.83 | 0.78 |

| Affect | 0.76 | 0.71 |

| Moral | 0.74 | 0.69 |

| Event | 0.72 | 0.68 |

| All Features | 0.89 | 0.82 |

Workflow Diagrams

NELA Feature Extraction Workflow

RAIDAR Detection Methodology

Integrated Feature Augmentation Framework

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My XGBoost model on forensic text data is running out of memory. What can I do?

XGBoost is designed to be memory efficient and can usually handle datasets containing millions of instances as long as they fit into memory. If you're encountering memory issues, consider these solutions:

- Use the

external memoryversion that processes data in chunks from disk - Implement distributed training frameworks mentioned in the XGBoost documentation

- For large text datasets in forensic applications, ensure you're using efficient feature representations like LFCCs which have demonstrated superior performance in forensic audio analysis [34] [35]

Q2: Why does my XGBoost model show slightly different results between runs on the same forensic text data?

This is expected behavior due to:

- Non-determinism in floating point summation order

- Multi-threading variations

- Potential data partitioning changes in distributed frameworks Though the exact numerical results may vary slightly, the general accuracy and performance on your forensic text detection task should remain consistent across runs [34].

Q3: Should I use BERT or XGBoost for CPT code prediction from pathology reports?

Research indicates the optimal choice depends on which text fields you utilize:

- When using only diagnostic text alone, BERT outperforms XGBoost

- When utilizing all report subfields, XGBoost significantly outperforms BERT

- Performance gains from using additional report subfields are particularly high for XGBoost models For forensic text classification tasks, consider experimenting with both architectures and different text sources to optimize performance [36].

Q4: How does XGBoost handle missing values in forensic text feature data?

XGBoost supports missing values by default in tree algorithms:

- Branch directions for missing values are learned during training

- The

missingparameter can specify what value represents missing data (default is NaN) - For linear boosters (gblinear), missing values are treated as zeros This automatic handling is particularly useful for forensic datasets where feature completeness can be variable [34].

Q5: What's the difference between using sparse vs. dense data with XGBoost for text features?

The treatment depends on your booster type:

- Tree booster treats "sparse" elements as missing values

- Linear booster treats sparse elements as zeros

- Conversion from sparse to dense matrix may fill missing entries with 0, which becomes a valid split value for decision trees For text-derived features, be consistent in your representation to ensure reproducible results [34].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Comparative Performance Analysis

Table 1: Performance Comparison of ML Classifiers on Pathology Report CPT Code Prediction

| Classifier | Text Features Used | Accuracy | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| BERT | Diagnostic text alone | Higher than XGBoost | Better with limited text sources |

| XGBoost | All report subfields | Significantly higher | Leverages diverse text features better |

| XGBoost | Diagnostic text alone | Lower than BERT | Less effective with limited context |

| SVM | Various text configurations | Moderate | Baseline performance |

Source: Adapted from comparative analysis of pathology report classification [36]

XGBoost Hyperparameter Tuning Protocol

Objective: Optimize XGBoost for forensic text classification tasks

Methodology:

- Initialize baseline model with default parameters

- Perform cross-validation using 10-fold validation on forensic text dataset

- Iteratively tune key parameters:

max_depth: Start with 3-10, typically begin at 6learning_rate: Test range 0.01-0.3, lower for more stable optimizationcolsample_bylevel: Experiment with 0.5-1.0 to prevent overfittingn_estimators: Increase until validation error plateaus (use early stopping)

- Apply regularization:

alpha(L1) andlambda(L2) for feature sparsity and overfitting reductiongammafor minimum loss reduction required for further partitioning

Expected Outcomes: Typical performance improvement of 15-20% in RMSE or comparable metric after tuning, as demonstrated in Boston housing price prediction studies [37].

BERT Fine-tuning Protocol for Forensic Text Detection

Objective: Adapt pre-trained BERT for specific forensic text classification tasks

Methodology:

- Data Preprocessing:

- Tokenize text using BERT tokenizer

- Segment text into sequences ≤512 tokens

- Add special tokens ([CLS], [SEP]) for classification tasks

Model Configuration:

- Use pre-trained BERT base (12-layer, 768-hidden) or large (24-layer, 1024-hidden)

- Add task-specific classification layer on [CLS] token representation

- Initialize with pre-trained weights except classification layer

Training Protocol:

- Lower learning rates (2e-5 to 5e-5) for fine-tuning

- Small batch sizes (16-32) due to memory constraints

- Progressive unfreezing of layers for stability

Application Note: In pathology report analysis, BERT demonstrated strong performance when using diagnostic text alone, suggesting its strength in capturing semantic nuances in specialized medical language [36].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Forensic Text Detection Experiments

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| LFCC (Linear Frequency Cepstral Coefficients) | Acoustic feature extraction capturing temporal and spectral properties | Superior performance in audio deepfake detection, outperforming MFCC and GFCC [35] |

| Gradient Boosting Framework | Ensemble learning with sequential error correction | XGBoost implementation for structured text-derived features [38] |

| Transformer Architecture | Contextual text representation using self-attention | BERT model for semantic understanding of medical texts [36] |

| Topic Modeling | Uncovering latent themes in text corpora | Identifying 20 topics in 93,039 pathology reports for feature augmentation [36] |

| SHAP/Grad-CAM | Model interpretability and feature importance | Explaining forensic model decisions for validation and trust [35] |

| Probability List Features | Capturing model family characteristics | PhantomHunter detection of privately-tuned LLM-generated text [39] |

| Cross-Validation | Robust performance estimation | 10-fold CV in XGBoost parameter tuning [37] |

| Contrastive Learning | Learning family relationships in feature space | PhantomHunter's approach to detecting text from unseen privately-tuned LLMs [39] |

Workflow Visualization

XGBoost for Forensic Text Classification

BERT vs XGBoost Comparative Workflow

Ensemble Method for Enhanced Forensic Detection

Writing Style Change Detection (SCD) for Multi-Author Document Analysis

Frequently Asked Questions