Essential Operational Requirements for Digital Evidence Acquisition Tools in Pharmaceutical Research

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on the operational requirements for digital evidence acquisition tools.

Essential Operational Requirements for Digital Evidence Acquisition Tools in Pharmaceutical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on the operational requirements for digital evidence acquisition tools. It covers foundational principles, practical methodologies, optimization strategies for complex data, and validation frameworks to ensure data integrity and legal admissibility. The guidance addresses the unique challenges of handling sensitive research data in compliance with stringent regulatory standards, leveraging the latest 2025 insights on digital forensics.

Core Principles: Building a Forensically Sound Foundation for Data Acquisition

Forensic soundness is a foundational concept in digital forensics, referring to the application of methods that ensure digital evidence is collected, preserved, and analyzed without alteration or corruption, thereby maintaining its legal admissibility [1]. In the context of research on digital evidence acquisition tools, upholding forensic soundness is not merely a best practice but an operational prerequisite. The core of forensic soundness rests upon several interdependent pillars: the use of reliable and repeatable methodologies, the maintenance of evidence integrity, and the preservation of a verifiable chain of custody [1].

This document outlines the application notes and experimental protocols essential for researchers and scientists developing the next generation of digital evidence acquisition tools. The requirements detailed herein are designed to ensure that novel tools and methods meet the stringent demands of the forensic science community and the judicial system.

Core Principles and Quantitative Metrics

The principles of forensic soundness can be operationalized into measurable metrics. The following table summarizes the core pillars and their corresponding operational requirements and validation metrics, crucial for tool design and testing.

Table 1: Core Pillars of Forensic Soundness and Associated Metrics for Tool Research

| Pillar | Operational Requirement | Key Validation Metric | Target Threshold for Tool Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reliability | Tools must produce consistent, accurate results across multiple trials and in various environments [2]. | Percentage of successful, error-free acquisitions per 1,000 operations. | >99.5% success rate [2]. |

| Repeatability | Methods must be documented to a degree that allows different operators to achieve the same results using the same tool and evidence source [1]. | Standard deviation of hash values across 100 repeated acquisitions of a standardized test dataset. | Zero standard deviation (identical hash values every time). |

| Evidence Integrity | The original evidence must remain completely unaltered, verified through cryptographic hashing [1]. | Successful verification of pre- and post-acquisition hash values (e.g., SHA-256, MD5) [1] [3]. | 100% hash match for every acquisition. |

| Minimal Handling | The acquisition process must interact with the original evidence source in a read-only manner [1]. | Number of write commands sent to the source device during acquisition, measured via hardware write-blocker logs. | Zero write commands. |

| Documented Chain of Custody | The tool must automatically generate a secure, tamper-evident log of all actions and handlers from the point of collection [1]. | Completeness and integrity of automated audit trails for 100% of operations. | 100% of actions logged with timestamps and user IDs; log integrity verifiable. |

Experimental Protocol for Validating Acquisition Tool Soundness

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for assessing the forensic soundness of a digital evidence acquisition tool under development.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Forensic Tool Validation Experiments

| Item | Function / Rationale |

|---|---|

| Write Blocker (Hardware) | Physically prevents data modification on the source evidence during acquisition, enforcing the principle of minimal handling [1]. |

| Forensic Imaging Tool (Reference) | A previously validated tool (e.g., FTK Imager) used as a control to verify the results of the tool under test [3]. |

| Standardized Test Drives | Storage devices (HDD, SSD) pre-populated with a known set of files, including deleted and hidden data, to provide a consistent baseline for testing. |

| Cryptographic Hashing Utility | Software (e.g., integrated into FTK Imager) to generate SHA-256 or MD5 hashes, which are the primary measure of evidence integrity [1] [3]. |

| Forensic Workstation | A dedicated, isolated computer system running a clean, documented operating environment to prevent external contamination of testing. |

Methodology

Preparation and Baseline Establishment

- Connect the standardized test drive to the forensic workstation via a hardware write blocker.

- Using the reference forensic imaging tool, create a forensic image (e.g.,

.ddor.E01format) of the test drive. This serves as the ground truth control. - Record the SHA-256 hash value of the control image.

- Document all hardware and software configurations in the audit log.

Tool Under Test - Acquisition Phase

- Without altering the setup, use the tool under test to acquire a forensic image of the same standardized test drive.

- The tool must be configured to generate its own SHA-256 hash of the acquired image.

- The tool must automatically log all operations, including timestamps, operator name, and any commands executed.

Integrity and Repeatability Analysis

- Integrity Verification: Compare the SHA-256 hash of the image generated by the tool under test against the hash of the control image from Step 1. The hashes must match exactly [1].

- Repeatability Testing: Repeat the acquisition process with the tool under test a minimum of 100 times. Calculate the success rate and confirm that every acquired image produces an identical hash, demonstrating repeatability.

- Reliability Testing: Execute the acquisition process on different forensic workstations and with different standardized test drives (e.g., featuring different filesystems like NTFS, FAT, ext4) to assess reliability across environments [3].

Minimal Handling Verification

- Analyze the hardware write blocker's internal log to confirm that zero write commands were transmitted to the source test drive during all acquisition phases.

Reporting

- Compile a report detailing the conformance of the tool under test with each metric outlined in Table 1. The report must include the complete chain of custody logs generated by the tool.

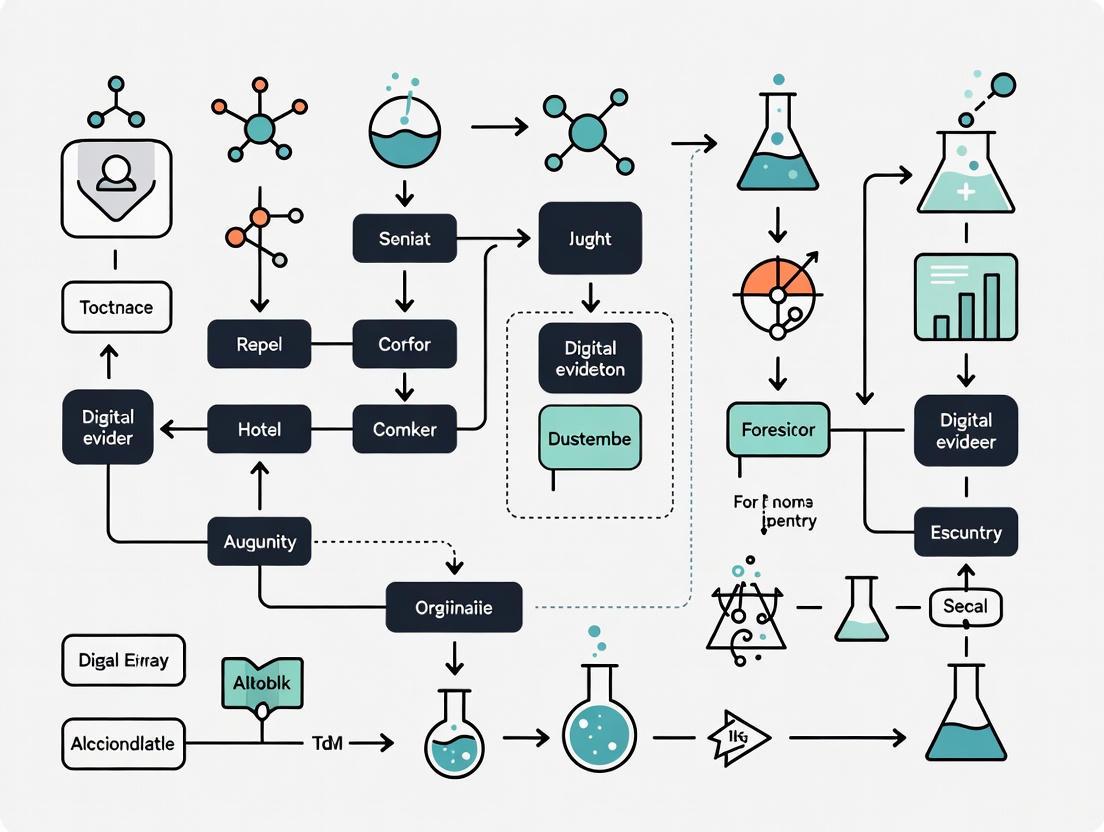

Workflow and Logical Relationships

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence and decision points in the experimental validation protocol for a forensic acquisition tool.

Validation Workflow for Forensic Acquisition Tools

Strategic Research Priorities

Aligning with the National Institute of Justice (NIJ) Forensic Science Strategic Research Plan, research into acquisition tools should focus on Strategic Priority I: "Advance Applied Research and Development in Forensic Science" [2]. Key objectives for tool developers include:

- I.5. Automated Tools To Support Examiners’ Conclusions: Developing systems that provide objective, quantitative support for examiner conclusions and assist with complex data analysis [2].

- I.6. Standard Criteria for Analysis and Interpretation: Research focused on establishing standard methods for qualitative and quantitative analysis and evaluating methods for expressing the weight of evidence [2].

- I.4. Technologies That Expedite Delivery of Actionable Information: Creating expanded triaging tools and techniques that yield actionable intelligence quickly while maintaining forensic soundness [2].

Furthermore, under Strategic Priority II, "Support Foundational Research in Forensic Science", it is critical to conduct foundational studies (e.g., black-box and white-box studies) to measure the accuracy, reliability, and sources of error in new acquisition tools [2]. This aligns directly with the experimental protocol outlined in Section 3.

The digital evidence lifecycle is a structured, methodical process essential for investigating cybercrime, corporate digital incidents, and fraud cases. For researchers focusing on the operational requirements of digital evidence acquisition tools, understanding this lifecycle is foundational. It ensures that digital evidence—from sources such as mobile devices, cloud servers, emails, and log files—is collected, preserved, and analyzed in a manner that maintains its forensic soundness, integrity, and legal admissibility [1]. The fragility of digital evidence, which can be easily altered, deleted, or corrupted, necessitates a rigorous, protocol-driven approach from the moment of identification to its final presentation in legal proceedings [1]. This document delineates the stages of this lifecycle, provides detailed experimental protocols for evidence acquisition, and catalogues the essential tools, thereby framing the operational parameters for future tool research and development.

The Stages of the Digital Evidence Lifecycle

The digital evidence lifecycle is a continuous process comprising several distinct but interconnected stages. Adherence to this lifecycle is critical for ensuring the reliability and defensibility of evidence in a court of law.

Stage 1: Identification

The initial phase involves recognizing and determining potential sources of digital evidence relevant to an investigation [4]. This requires a systematic survey of the digital environment to locate devices and data that may contain pertinent information.

Key Activities and Research Considerations:

- Device Identification: Locating physical devices such as computers, smartphones, tablets, servers, and emerging IoT devices like drones and smart vehicles [4] [5].

- Data Source Mapping: Identifying potential data repositories, including cloud storage accounts, network logs, social media sites, and encrypted volumes [4] [1].

- Research Imperative: Acquisition tools must evolve to maintain a comprehensive catalog of recognizable devices and data sources, especially with the proliferation of new technologies.

Stage 2: Preservation

Following identification, the immediate priority is to secure and preserve the integrity of the digital evidence to prevent any tampering, alteration, or destruction [4] [1]. This stage is where the chain of custody is initiated.

Key Activities and Research Considerations:

- Evidence Isolation: Securing the physical device and, where applicable, isolating it from networks to prevent remote wiping or data corruption [6].

- Forensic Imaging: Creating a bit-for-bit forensic copy (an "image") of the original storage media using write-blockers to ensure the original data is not modified [1].

- Integrity Verification: Applying hash algorithms (e.g., SHA-256) to generate a unique digital fingerprint of the evidence, which can be verified at any point to confirm it remains unaltered [7] [1].

- Research Imperative: Research into faster, more reliable imaging for high-capacity storage and robust methods for capturing volatile data (e.g., from RAM) is crucial [1].

Stage 3: Collection

This phase involves the systematic, forensically sound gathering of the identified digital evidence [4]. Collection must be performed using validated tools and techniques to ensure the data is legally collected and its provenance is documented.

Key Activities and Research Considerations:

- Data Acquisition: Using specialized tools to extract data from the identified sources. This can range from logical extraction (accessible files) to physical extraction (a full bit-by-bit copy of the storage) [5].

- Chain of Custody Documentation: Meticulously logging every individual who handles the evidence, along with the time, date, and purpose for access [4] [1].

- Research Imperative: Acquisition tools must support a wide array of file systems and device protocols and provide built-in, tamper-evident audit trails for chain of custody.

Stage 4: Examination

In the examination phase, forensic experts scrutinize the collected evidence using specialized tools to identify and recover relevant information [4]. This often involves processing large datasets to uncover hidden or deleted data.

Key Activities and Research Considerations:

- Data Recovery: Attempting to recover deleted files and fragments from unallocated disk space [8] [3].

- Metadata Analysis: Examining file metadata, such as creation and modification timestamps, to build a timeline of events [5].

- Data Carving: Searching raw data streams for file signatures to reconstruct files without relying on file system structures [3].

- Research Imperative: Tool research should focus on enhancing the speed and accuracy of data carving and recovery algorithms to handle increasingly large and complex storage media.

Stage 5: Analysis

The analysis phase is the interpretation of the examined data to draw meaningful conclusions that are relevant to the investigation [4]. This involves correlating data points, identifying patterns, and reconstructing events.

Key Activities and Research Considerations:

- Data Correlation: Linking information from multiple sources (e.g., linking a user's chat logs to their cloud storage activity) to build a comprehensive narrative [4].

- Timeline Reconstruction: Creating a chronological sequence of events based on file activity, registry entries, and log files [3].

- Application of AI: Using artificial intelligence and machine learning for pattern recognition, anomaly detection, and to analyze large volumes of unstructured data like texts and images [7] [5].

- Research Imperative: There is a significant need for developing and integrating transparent, reliable AI models that can assist in analysis while providing explanations for their findings to withstand legal scrutiny.

Stage 6: Presentation

The presentation phase involves compiling the findings into a clear, concise, and understandable format for stakeholders such as legal teams, corporate management, or court officials [4].

Key Activities and Research Considerations:

- Report Generation: Creating detailed reports that summarize the methodology, findings, and conclusions in a manner accessible to non-technical audiences [4].

- Expert Testimony: Providing witness testimony in legal proceedings to explain the forensic process and validate the evidence [4] [1].

- Research Imperative: Acquisition and analysis tools must feature robust, customizable reporting modules that can automatically generate legally sound and easily digestible reports.

Stage 7: Documentation and Reporting

While documentation occurs throughout the lifecycle, this final phase involves the consolidation of all records, logs, and findings into a comprehensive package that supports the investigation's integrity and allows for future peer review [4].

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow and key activities of this digital evidence lifecycle:

Digital Evidence Lifecycle Workflow: A sequential process from evidence identification through to comprehensive documentation, with color-coding for phases (green: pre-analysis, blue: analysis, red: post-analysis).

Experimental Protocols for Digital Evidence Acquisition

For research and development purposes, standardized protocols are necessary to validate and compare the performance of digital evidence acquisition tools. The following protocols provide a framework for rigorous testing.

Protocol: Forensic Disk Imaging and Integrity Verification

This protocol outlines the methodology for creating a forensically sound copy of a storage device, a fundamental process in digital evidence collection.

1. Objective: To create a verifiable, bit-for-bit duplicate of a source storage device without altering the original data, and to confirm the integrity of the duplicate throughout the investigation lifecycle.

2. Materials:

- Source storage device (e.g., SATA/NVMe SSD, HDD)

- Forensic workstation with adequate storage capacity

- Write-blocker hardware device

- Digital forensics software (e.g., FTK Imager, EnCase, X-Ways Forensics)

- Hashing utility (integrated into forensics software or standalone)

3. Methodology: 1. Preparation: Document the make, model, and serial number of the source device. Connect the write-blocker to the forensic workstation. Connect the source storage device to the input port of the write-blocker. 2. Verification of Write-Block: Power on the write-blocker and verify its status indicates that write-protection is active. The forensic workstation should not automatically mount the source device's file system. 3. Acquisition: Launch the digital forensics software. Select the option to create a disk image. Choose the source device (via the write-blocker) as the source. Select a destination path on the forensic workstation's storage with sufficient free space. Choose a forensic image format (e.g., .E01, .AFF). Configure the software to compute a hash value (SHA-256 is recommended) during the acquisition process. Initiate the imaging process. 4. Integrity Check: Upon completion, record the hash value generated by the software. Verify this hash value each time the image file is accessed or moved. Any discrepancy indicates data corruption and renders the evidence unreliable.

4. Data Analysis: The primary quantitative data is the hash value. A matching hash at the start and end of any handling period confirms integrity. The success of the protocol is binary: either the hashes match and the image is valid, or they do not.

Protocol: On-Site Mobile Device Acquisition for Volatile Data

This protocol addresses the growing challenge of preserving data on modern mobile devices, where evidence can degrade rapidly after seizure [6].

1. Objective: To perform a rapid, on-site acquisition of a mobile device to capture volatile and ephemeral data that may be lost if the device is powered down or transported to a lab.

2. Materials:

- Mobile device (smartphone/tablet)

- Trusted forensic acquisition tool (e.g., Cellebrite UFED, Magnet AXIOM, Oxygen Forensics)

- Forensic workstation or laptop with acquisition software

- Faraday bag or box to isolate the device from networks (if deemed necessary without triggering security locks)

3. Methodology: 1. Risk Assessment: Upon seizure, assess the device's state (locked/unlocked, battery level). Determine if on-site acquisition is feasible and legally authorized. 2. Device Isolation: If the device is unlocked, place it in a Faraday bag to prevent network connectivity that could trigger remote wipe, while considering that some security features may be activated by loss of signal [6]. 3. Rapid Acquisition: Connect the device to the acquisition laptop using an appropriate cable. Use the forensic tool to perform the most extensive extraction possible given the device's state (e.g., logical, file system, or physical extraction). Prioritize extraction methods that capture the unified logs and other ephemeral artifacts first, as these are most susceptible to loss [6]. 4. Documentation: Document the exact time of acquisition, the device state, and the extraction method used. Any device reboots induced by the tool should be noted, as this can affect data integrity [6].

4. Data Analysis: The outcome is the extracted data package. The protocol's success can be measured by the completeness of the extraction (e.g., successfully obtaining a full file system extraction versus a limited logical extraction) and the subsequent ability to analyze key artifacts like application data and system logs.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

For researchers developing and testing digital evidence acquisition tools, the "reagents" are the software and hardware tools that form the experimental environment. The table below catalogs essential solutions, their functions, and relevance to operational research.

Table 1: Essential Digital Forensics Tools for Research and Operations

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function in Lifecycle | Research Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| FTK Imager [3] [1] | Software | Preservation, Collection: Creates forensic images of drives and verifies integrity via hashing. | Foundational tool for testing and validating the core acquisition process; baseline for integrity checks. |

| Cellebrite UFED [8] [5] | Hardware/Software Suite | Collection, Examination: Extracts data from mobile devices, including physical and cloud acquisitions. | Critical for researching mobile forensics challenges, including encryption and rapid data extraction. |

| Autopsy / The Sleuth Kit [8] [3] | Open-Source Software | Examination, Analysis: Performs file system analysis, data carving, and timeline reconstruction. | Accessible platform for developing and testing new analysis modules and algorithms. |

| Magnet AXIOM [8] [3] | Commercial Software | Collection, Examination, Analysis: Acquires and analyzes evidence from computers, mobile devices, and cloud sources. | Represents integrated suite capabilities; useful for studying workflow efficiency and AI integration. |

| X-Ways Forensics [8] [3] | Commercial Software | Examination, Analysis: Analyzes disk images, recovers data, and supports deep file system inspection. | Known for efficiency with large datasets; relevant for research on processing speed and memory management. |

| Volatility [8] | Open-Source Software | Examination, Analysis: Analyzes RAM dumps to uncover running processes, network connections, and ephemeral data. | Essential for research on volatile memory forensics and combating anti-forensic techniques [5]. |

| Belkasoft X [3] [5] | Commercial Software | Collection, Examination, Analysis: Gathers and analyzes evidence from multiple sources (PC, mobile, cloud) in a single platform. | Ideal for studying centralized forensics workflows and the application of AI (e.g., BelkaGPT) in analysis. |

| Write Blocker [1] | Hardware | Preservation: Physically prevents data writes to a storage device during the imaging process. | A mandatory control tool in any acquisition experiment to ensure the forensic soundness of the process. |

The digital evidence lifecycle provides the essential framework within which all digital forensic tools must operate. For researchers, a deep understanding of the challenges at each stage—from the volatility of mobile data [6] to the complexities of AI-assisted analysis [5]—defines the operational requirements for the next generation of acquisition and analysis tools. The protocols and tool catalog presented herein offer a foundation for systematic research and development. Future work must focus on standardizing methods, enhancing automation to manage data volume [7] [5], and ensuring that new tools are not only technically proficient but also legally defensible and accessible to the professionals who safeguard digital truth.

The reliability of digital evidence in legal proceedings is contingent upon the rigorous application of legal standards and technical protocols. For researchers developing and evaluating digital evidence acquisition tools, understanding the intersection of the Daubert standard for expert testimony admissibility and the ISO/IEC 27037 guidelines for digital evidence handling is fundamental. These frameworks collectively establish operational requirements that tools must satisfy to produce forensically sound and legally admissible results. Recent amendments to Federal Rule of Evidence 702 have further clarified that the proponent must demonstrate the admissibility of expert testimony "more likely than not," reinforcing the judiciary's gatekeeping role [9]. This document outlines application notes and experimental protocols to guide tool research and development within this legally complex landscape.

Conceptual Foundations and Comparative Analysis

The Daubert Standard: Legal Admissibility Framework

The Daubert standard, originating from Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (1993), provides the federal court system with criteria for assessing the admissibility of expert witness testimony [10]. The standard establishes the trial judge as a gatekeeper and outlines five factors for evaluating scientific validity:

- Testability: Whether the expert's technique or theory can be (and has been) tested.

- Peer Review: Whether the technique or theory has been subjected to peer review and publication.

- Error Rate: The known or potential rate of error of the technique.

- Standards: The existence and maintenance of standards controlling the technique's operation.

- General Acceptance: The degree to which the technique is generally accepted in the relevant scientific community [10] [11].

This standard was subsequently expanded in Kumho Tire Co. v. Carmichael (1999) to apply to all expert testimony, not just "scientific" knowledge [10]. The 2023 amendment to Federal Rule of Evidence 702 explicitly places the burden on the proponent to demonstrate by a preponderance of the evidence that all admissibility requirements are met [9].

ISO/IEC 27037: Technical Guidelines for Digital Evidence

ISO/IEC 27037 provides international guidelines for handling digital evidence, specifically addressing the identification, collection, acquisition, and preservation of digital evidence [12] [13]. Its primary objective is to ensure evidence is handled in a legally sound and forensically reliable manner. The standard provides guidance on preserving the integrity of evidence and defining roles for personnel involved in the process [13]. It is particularly valuable for establishing practices that support the authenticity and reliability of digital evidence in legal contexts.

Comparative Analysis of Admissibility Frameworks

The table below synthesizes the key components of the Daubert Standard and ISO/IEC 27037, highlighting their complementary roles in ensuring the legal admissibility of digital evidence.

Table 1: Comparison of Daubert Standard and ISO/IEC 27037 Guidelines

| Aspect | Daubert Standard (Legal) | ISO/IEC 27037 (Technical) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Admissibility of expert testimony in court [10]. | Handling of digital evidence from identification to preservation [13]. |

| Core Principles | Reliability, Relevance, Scientific Validity [10]. | Integrity, Authenticity, Reliability, Chain of Custody [13]. |

| Key Requirements | Testing, Peer review, Error rates, Standards, General acceptance [10]. | Proper identification, collection, acquisition, and preservation procedures [13]. |

| Role in Evidence Admissibility | Directly determines if expert testimony about evidence is admissible [9]. | Establishes a foundation for evidence integrity, supporting its admissibility [12]. |

| Application in Tool Research | Provides legal criteria for validating tool reliability and methodology [11]. | Offers a procedural framework for testing tool performance in evidence handling [14]. |

Integrated Framework for Digital Evidence Tool Research

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for developing and validating digital evidence acquisition tools, synthesing requirements from both the Daubert Standard and ISO/IEC 27037.

Digital Evidence Tool R&D Workflow

Experimental Protocols for Tool Validation

Protocol 1: Comparative Tool Performance and Error Rate Analysis

This protocol is designed to generate quantifiable performance metrics and error rates, which are critical factors under the Daubert standard [11].

Objective: To quantitatively compare the performance of a tool under evaluation against established commercial and open-source digital forensic tools in a controlled environment.

Methodology:

- Control Environment Setup: Create a standardized testing environment using forensically wiped and prepared storage media. The test dataset should include a pre-determined mix of active and deleted files of various formats, along with specific application artifacts (e.g., from messaging apps or browsers) [11].

- Tool Selection: Include a representative mix of tools:

- Test Scenarios: Execute three core forensic tasks across all tools [11]:

- Data Preservation & Collection: Create a forensic image and verify integrity via hash values (e.g., SHA-256).

- File Recovery: Recover deleted files using data carving techniques.

- Artifact Searching: Execute targeted searches for specific data artifacts.

- Replication: Perform each experiment in triplicate to establish repeatability and consistency of results [11].

Data Collection and Analysis:

- Primary Metrics: Measure the percentage of artifacts successfully recovered/identified in each scenario. Calculate the tool's error rate by comparing acquired artifacts against the known control reference [11].

- Supplementary Metrics: Record processing speed, system resource utilization, and accuracy of generated metadata.

Table 2: Sample Results Table for Comparative Tool Performance

| Tool Category | Tool Name | Data Preservation\nHash Integrity Verified | File Recovery Rate (%) | Artifact Search\nAccuracy (%) | Measured Error Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commercial | FTK | 100% | 95.2 | 98.5 | 0.8 |

| Commercial | Forensic MagiCube | 100% | 93.8 | 97.2 | 1.1 |

| Open-Source | Autopsy | 100% | 92.1 | 95.7 | 1.5 |

| Open-Source | ProDiscover Basic | 100% | 90.5 | 94.3 | 2.0 |

| Tool Under Eval | TUE v1.0 | 100% | 94.5 | 96.8 | 1.2 |

Protocol 2: Integrity Verification Under ISO/IEC 27037

This protocol directly addresses the integrity and authenticity requirements of ISO/IEC 27037, which form the bedrock for evidence admissibility.

Objective: To validate that a tool maintains the integrity of original evidence throughout the acquisition process, establishing a reliable chain of custody.

Methodology:

- Baseline Establishment: Before acquisition, calculate and record the original hash value (SHA-256 or MD5) of the source evidence media [13].

- Evidence Acquisition: Use the tool to create a forensic image. The process must be performed on a write-blocked interface to prevent modification of the original source.

- Integrity Verification: Upon completion, calculate the hash value of the acquired forensic image. The hash of the image must exactly match the hash of the original source to prove integrity was maintained [12] [13].

- Chain of Custody Logging: The tool must generate a detailed, tamper-evident log file documenting all actions, timestamps, and the operator involved in the acquisition process.

Protocol 3: Validation of Advanced Forensic Techniques

This protocol assesses a tool's ability to handle complex scenarios, such as dealing with application-induced data compression or encryption, which tests the limits of its reliability.

Objective: To evaluate a tool's capability to acquire and validate evidence that has been altered by application-level processes (e.g., image compression on social media platforms).

Methodology:

- Scenario Simulation: Generate data using target applications (e.g., TikTok Shop) known to apply compression or transformation to user-uploaded content [12].

- Data Acquisition: Use the tool to acquire the transformed data from the device or network stream.

- Content-Level Validation: When cryptographic hashes fail due to content transformation, employ supplementary validation techniques [12]:

- Optical Character Recognition (OCR): Extract textual content from images for comparison.

- Levenshtein Distance Algorithm: Quantify the textual similarity between the original text and the OCR-extracted text [12].

- Image Forensic Analysis (e.g., using Forensically platform): Analyze for consistency in compression artifacts, noise levels, and other metadata to detect potential tampering and assess authenticity [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Digital Forensic Research Materials and Tools

| Item / Solution | Function / Purpose in Research |

|---|---|

| Write-Blockers | Hardware or software interfaces that prevent any data from being written to the source evidence media during acquisition, preserving integrity [13]. |

| Forensic Imaging Tools | Software (e.g., FTK Imager, dc3dd) and hardware designed to create a bit-for-bit copy (forensic image) of digital storage media. |

| Validated Hash Algorithms | Cryptographic functions (e.g., SHA-256, MD5) used to generate a unique digital fingerprint of evidence, crucial for verifying integrity [12] [13]. |

| Open-Source Forensic Suites | Tools like Autopsy and The Sleuth Kit provide a transparent, peer-reviewable platform for developing and testing new forensic methods [11]. |

| Controlled Test Data Sets | Curated collections of digital files and artifacts with known properties, used as a ground truth for validating tool performance [11]. |

| Evidence Bagging Systems | Physical and digital systems for securely storing evidence and maintaining a documented chain of custody [13]. |

Workflow for Evidence Authentication and Admissibility

The following diagram details the sequential workflow for authenticating digital evidence and preparing for its admissibility in court, integrating both technical and legal steps.

Digital Evidence Authentication Workflow

Application Note: Quantifying the Operational Challenges

For research into next-generation digital evidence acquisition tools, understanding the scale and technical nature of operational challenges is a prerequisite. The following data, synthesized from current market analyses and threat landscapes, provides a quantitative foundation for defining tool requirements and benchmarking performance.

Table 1: Quantitative Analysis of Core Operational Challenges in Digital Evidence Acquisition

| Challenge Dimension | Key Metric | 2025 Projection / Observed Value | Research Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Volume & Variety | Global Digital Evidence Management Market Size [15] | USD 9.1 Billion (2025) | Justifies investment in scalable, high-throughput acquisition toolkits. |

| Projected Market Value by 2034 [15] | USD 28.5 Billion | Indicates long-term, sustained growth in data volume, necessitating future-proof tools. | |

| Data Residing in Cloud Environments [16] | >60% | Mandates native cloud acquisition capabilities, moving beyond physical device imaging. | |

| Anti-Forensics Proliferation | Ransomware Attacks (Q1 2025) [17] | 46% Surge | Highlights need for tools resilient to data destruction and encryption techniques. |

| Deepfake Fraud Attempts (3-year period) [18] | 2137% Increase | Drives requirement for integrated media authenticity verification in acquisition phases. | |

| Cloud Storage Complexity | Leading Deployment Model [15] | Cloud & Hybrid | Requires acquisition tools to interface with cloud APIs and maintain chain of custody remotely. |

Experimental Protocols for Challenge Mitigation

This section outlines detailed, actionable methodologies for researching and validating evidence acquisition techniques against the defined challenges. These protocols are designed for use in controlled laboratory environments to ensure reproducible results.

Protocol: Acquisition and Integrity Verification from Volatile Mobile Data

Objective: To establish a reliable methodology for the immediate acquisition of data from modern mobile devices, countering data degradation and anti-forensic features [6].

Research Reagent Solutions:

| Item | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|

| Mobile Device Security Profiler | Software to identify and log device-specific security settings (e.g., USB restrictions, location-based locks) that may trigger data wiping. |

| Faraday Enclosure / Signal Blocker | Prevents the device from receiving remote wipe commands or updating its location context upon seizure. |

| Write-Blocking Hardware Bridge | Ensures a forensically sound physical connection between the device and the acquisition workstation. |

| Volatile Memory Acquisition Tool | Software designed to perform a live RAM extraction via established techniques (e.g., JTAG, Chip-off may be considered for non-volatile storage). |

| Cryptographic Hash Algorithm Library | (e.g., SHA-256, SHA-3) to generate unique digital fingerprints for all acquired data images. |

Methodology:

- Immediate Isolation: Upon seizure in the test environment, immediately place the device into a Faraday enclosure to isolate it from all networks [6].

- Rapid Profiling: Using the Mobile Device Security Profiler, document the device's state, focusing on identifying threats to data persistence, such as auto-reboot triggers or anti-forensic applications.

- Stabilized Connection: Connect the device to the acquisition workstation using the Write-Blocking Hardware Bridge.

- Prioritized Acquisition: a. Unified Logs Capture: First, extract the unified logs or any other ephemeral system artifacts before any other extensive interaction, as these can be lost during a full file system extraction [6]. b. File System Acquisition: Proceed with a full file system extraction using appropriate tools.

- Integrity Verification: Calculate the cryptographic hash (e.g., SHA-256) of the acquired evidence image using the Hash Algorithm Library. This hash must be documented and used for verification in all future analysis to prove data integrity [7].

Diagram: Mobile Evidence Acquisition Workflow. This protocol prioritizes volatile data to counter anti-forensics [6].

Protocol: Forensic Acquisition via Cloud Service APIs

Objective: To acquire digital evidence from cloud platforms in a manner that preserves legal admissibility, overcoming challenges of data fragmentation and jurisdictional inaccessibility [7] [5].

Research Reagent Solutions:

| Item | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|

| Cloud API Client Simulator | A tool that mimics an official application client to interact with cloud service APIs (e.g., for social media or storage platforms) and download user data [5]. |

| Valid User Account Credentials | Legally obtained credentials for a test account, necessary for the API client to authenticate and access data as the user would [5]. |

| Chain of Custody Logger | Software that automatically logs all steps of the API interaction, including timestamps, commands sent, and data received. |

| Evidence Encryption Module | Software to encrypt the acquired evidence dataset immediately after download for secure storage. |

Methodology:

- Legal Authority Verification: Confirm that the acquisition is authorized by a legal warrant or appropriate legal instrument for the test.

- API Client Configuration: Configure the Cloud API Client Simulator with the Valid User Account Credentials. The server will perceive this as legitimate user activity [5].

- Auditable Data Request: Execute the data request through the simulator. The Chain of Custody Logger must run concurrently, recording every API call and response metadata.

- Secure Data Ingestion: Download the evidence data from the cloud API. Upon completion, use the Evidence Encryption Module to encrypt the entire dataset.

- Integrity & Custody Sealing: Generate a cryptographic hash of the encrypted evidence file. The audit log from the Chain of Custody Logger, the evidence hash, and details of the encryption key are then packaged as a single, sealed record.

Diagram: Cloud Evidence Acquisition via API. This method legally bypasses some jurisdictional issues [5].

Protocol: Detection of Anti-Forensic "Timestomping"

Objective: To validate a multi-faceted methodology for detecting the manipulation of file system timestamps (timestomping), a common anti-forensic technique used to disrupt timeline analysis [19].

Research Reagent Solutions:

| Item | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|

| $MFT Parsing Tool | Software (e.g., istat from Sleuth Kit, MFTEcmd) capable of extracting and displaying both $STANDARD_INFO ($SI) and $FILE_NAME ($FN) attributes from the NTFS Master File Table. |

| $UsnJrnl ($J) Parser | A tool to parse the NTFS Update Sequence Number Journal, which logs file system operations. |

| File System Image | A forensic image (e.g., .E01, .aff) of an NTFS volume for analysis. |

Methodology:

- $MFT Record Analysis:

a. Using the $MFT Parsing Tool, extract the MACB timestamps for a file from both the

$SIand$FNattributes. b. Compare Creation Times: A strong indicator of timestomping is present if the$SIcreation time is earlier than the$FNcreation time, as user-level tools can typically only manipulate$SI[19]. c. Check Timestamp Resolution: Inspect the sub-second precision of the timestamps. A value ending in seven zeros (e.g.,.0000000) is highly unusual in a genuine timestamp and suggests tool-based manipulation [19]. - UsnJrnl Log Correlation: a. Using the $UsnJrnl ($J) Parser, review the log entries for the file in question. b. Search for log entries with the "BasicInfoChange" update reason, which is recorded when a file's metadata (like timestamps) is altered. A sequence of "BasicInfoChange" followed by "BasicInfoChange | Close" is indicative of timestomping activity [19].

- Correlation: Correlate findings from both methods to build a robust evidence profile confirming the act of timestomping.

Diagram: Timestomping Detection Logic. The protocol uses multiple artifacts to reveal timestamp manipulation [19].

From Theory to Practice: Implementing Effective Acquisition Workflows

Digital forensics tools are specialized software applications designed to identify, preserve, extract, analyze, and present digital evidence from devices such as computers, smartphones, networks, and cloud platforms [20]. In 2025, these tools have become indispensable for investigators across law enforcement, corporate security, and incident response teams tackling increasingly complex digital environments [8] [20]. The core challenge for forensic professionals lies in selecting appropriate tools that balance technical capability, legal admissibility, operational efficiency, and budgetary constraints [21]. This selection process requires careful consideration of organizational needs, investigator expertise, and the specific demands of modern digital evidence acquisition.

The fundamental divide in the digital forensics tool landscape exists between open-source and commercial solutions, each with distinct advantages and limitations. Open-source tools like Autopsy and The Sleuth Kit offer cost-effective, transparent, and customizable platforms supported by developer communities [8] [21]. Conversely, commercial tools such as Cellebrite UFED and Magnet AXIOM provide dedicated support, user-friendly interfaces, and advanced features but often at substantial licensing costs [8] [20]. Recent research indicates that properly validated open-source tools can produce forensically sound results comparable to commercial alternatives, though they often face greater scrutiny regarding legal admissibility due to the absence of standardized validation frameworks [11].

Comparative Analysis: Open-Source vs. Commercial Digital Forensics Tools

Quantitative Comparison of Tool Attributes

Table 1: Core Functional Comparison of Digital Forensics Tool Types

| Evaluation Criteria | Open-Source Tools | Commercial Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Acquisition Cost | Free [21] | High licensing fees ($3,995-$11,500+) [20] |

| Customization Potential | High (modifiable source code) [21] | Limited (vendor-controlled development) [21] |

| Technical Support Structure | Community forums and documentation [8] | Dedicated vendor support with service agreements [21] |

| Transparency & Verification | High (visible source code) [21] | Limited (proprietary black-box systems) [11] |

| Legal Admissibility Track Record | Requires additional validation [11] | Established court acceptance [11] |

| User Interface Complexity | Often technical with command-line emphasis [8] | Typically graphical and workflow-oriented [21] |

| Training Requirements | Significant for non-technical users [8] | Structured training programs available [20] |

| Update Frequency & Mechanism | Community-driven, irregular releases [21] | Scheduled, vendor-managed updates [8] |

Table 2: Technical Capability Assessment by Digital Evidence Source

| Evidence Source | Leading Open-Source Tools | Leading Commercial Tools | Key Capability Differences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computer Systems | Autopsy, The Sleuth Kit, PALADIN [8] [20] | EnCase Forensic, FTK, X-Ways Forensics [8] [20] | Commercial tools offer better processing speed for large datasets and more advanced reporting features [8] |

| Mobile Devices | ALEX (emerging) [22] | Cellebrite UFED, Oxygen Forensic Detective [8] [20] | Commercial tools dominate with extensive device support and encrypted app decoding [20] |

| Network Traffic | Wireshark [20] | Various specialized commercial solutions | Open-source options provide robust capabilities for protocol analysis [20] |

| Memory Forensics | Volatility [8] | Magnet AXIOM, FTK [8] [20] | Open-source tools offer strong capabilities but require greater technical expertise [8] |

| Cloud Data | Limited specialized options | Magnet AXIOM, Cellebrite UFED [8] [20] | Commercial tools have more developed cloud API integrations [8] |

Qualitative Assessment of Implementation Considerations

Beyond technical capabilities, organizations must consider implementation factors when selecting digital forensics tools. Open-source solutions present lower financial barriers but often require significant investments in specialized personnel and training to achieve proficiency [21]. The transparency of open-source code allows for peer review and customization, potentially enhancing trust in tool methodologies, though this same flexibility can introduce variability in implementation [11]. Commercial tools typically offer more streamlined implementation paths with vendor support, standardized training programs, and established operational workflows, though often at the cost of vendor lock-in and limited customization options [21].

Legal admissibility remains a significant differentiator, with commercial tools generally having more established judicial acceptance based on historical usage, certification programs, and vendor testimony [11]. However, recent research demonstrates that open-source tools can produce equally reliable results when proper validation frameworks are implemented, suggesting that methodological rigor may ultimately outweigh commercial validation in evidentiary proceedings [11].

Experimental Protocol: Validation Framework for Tool Selection

Controlled Testing Methodology for Digital Forensics Tools

A rigorous experimental protocol is essential for validating both open-source and commercial digital forensics tools to ensure they meet operational requirements. The following methodology, adapted from controlled testing approaches used in recent studies, provides a structured framework for tool evaluation [11]:

Phase 1: Test Environment Preparation

- Establish two identical forensic workstations with standardized hardware specifications (minimum 32GB RAM, 2TB SSD storage, multi-core processors)

- Implement a controlled data set containing known artifacts across three categories: preserved active files, recoverable deleted files, and specific search targets

- Create cryptographic hash inventories (MD5, SHA-256) of all test data for verification purposes

- Document baseline system state before tool installation to detect any environmental modifications

Phase 2: Tool Implementation and Configuration

- Install candidate tools following vendor recommendations for commercial products and established best practices for open-source solutions

- Configure uniform processing parameters across all tools: hash verification, indexing options, and output formats

- Document all configuration changes and customizations, particularly for open-source tools requiring compilation or dependency resolution

- Validate tool functionality through preliminary tests with standardized data sets

Phase 3: Experimental Test Scenarios

- Conduct triplicate testing for each tool across three evidence scenarios:

- Preservation and Collection: Verify ability to create forensically sound images without altering original data

- Data Recovery: Assess file carving capabilities and deleted file recovery through controlled data sets

- Targeted Search: Evaluate keyword searching, regex capabilities, and artifact-specific filtering

- Calculate error rates by comparing acquired artifacts against control references

- Measure processing times and resource utilization (CPU, memory, storage I/O) for performance benchmarking

Phase 4: Results Validation and Documentation

- Verify extracted evidence against known control hashes and contents

- Document all procedural steps, unexpected behaviors, and tool limitations observed during testing

- Generate comprehensive reports suitable for inclusion in legal proceedings if required

- Assess each tool against the Daubert Standard criteria: testability, peer review, error rates, and general acceptance [11]

Tool Selection Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Tool selection and validation workflow for digital forensics tools.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Digital Forensics Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Digital Forensics Tool Validation

| Research Reagent | Function in Experimental Protocol | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Data Sets | Controlled collections of known digital artifacts for tool capability verification | Created mixes of file types (documents, images, databases), deleted content, and system artifacts |

| Forensic Workstations | Standardized hardware platforms for consistent tool performance testing | Configured systems with write-blockers, adequate storage, and processing power for large data sets |

| Hash Verification Tools | Integrity checking for evidence preservation and tool output validation | MD5, SHA-1, and SHA-256 algorithms implemented through built-in tool features or external utilities |

| Legal Standards Framework | Criteria for evaluating evidentiary admissibility potential | Daubert Standard factors: testability, peer review, error rates, and general acceptance [11] |

| Performance Metrics System | Quantitative measurement of tool efficiency and resource utilization | Processing time benchmarks, memory consumption logs, and computational resource monitoring |

| Documentation Templates | Standardized reporting for experimental results and procedure documentation | Chain of custody forms, tool configuration logs, and validation certificate templates |

Operational Implementation Framework

Integrated Tool Deployment Strategy

Successful implementation of digital forensics tools requires a strategic approach that leverages the complementary strengths of both open-source and commercial solutions. Organizations should consider a hybrid model that utilizes commercial tools for core investigative workflows where their reliability, support, and court acceptance are most valuable, while deploying open-source tools for specialized tasks, verification of commercial tool results, and situations requiring customization [21]. This approach provides both the operational efficiency of commercial solutions and the flexibility, transparency, and cost-control of open-source alternatives.

Implementation planning must address several critical factors: data volume handling capabilities, integration with existing security infrastructure, compliance with relevant legal standards, and long-term maintenance requirements [23]. For organizations with limited resources, a phased implementation approach may be appropriate, beginning with open-source tools for basic capabilities while gradually introducing commercial solutions as needs evolve and budgets allow [21]. Regardless of the specific tools selected, maintaining comprehensive documentation of all procedures, tool configurations, and validation results is essential for ensuring repeatability and defending methodological choices in legal proceedings [11] [23].

Tool Selection Decision Framework Visualization

Diagram 2: Decision framework for selecting between open-source and commercial digital forensics tools.

The selection between open-source and commercial digital forensics tools represents a critical decision point that significantly impacts investigative capabilities, operational efficiency, and evidentiary integrity. Rather than a binary choice, modern digital forensics operations benefit most from a strategic integration of both tool types, leveraging the respective strengths of each approach. Commercial tools provide validated, supported solutions for core investigative workflows where reliability and legal admissibility are paramount, while open-source solutions offer flexibility, transparency, and cost-effectiveness for specialized tasks and methodological verification.

The evolving landscape of digital evidence, characterized by increasing data volume, device diversity, and encryption adoption, necessitates rigorous tool validation frameworks regardless of solution type. By implementing structured testing protocols and maintaining comprehensive documentation of tool capabilities and limitations, organizations can ensure their digital forensics tools meet both operational requirements and legal standards. As the field continues to advance, the distinction between open-source and commercial solutions may increasingly focus on implementation and support models rather than fundamental capabilities, with both approaches playing essential roles in comprehensive digital investigations.

Digital evidence acquisition forms the foundational first step in any forensic investigation, directly determining the scope, integrity, and ultimate admissibility of any evidence recovered. Within the context of researching and developing digital evidence acquisition tools, understanding these core techniques is paramount for establishing operational requirements. This document details the essential protocols for three critical acquisition domains: disk imaging, RAM capture, and mobile device extraction. Each technique addresses unique evidence volatility and complexity challenges, necessitating specialized tools and methodologies to meet the rigorous standards of scientific and legal scrutiny. The following sections provide detailed application notes and experimental protocols to guide tool selection, implementation, and validation for researchers and development professionals.

Disk Imaging

Disk imaging is the process of creating a complete, bit-for-bit copy of a storage device, preserving not only active files but also deleted data, slack space, and file system metadata. This forensic soundness is crucial for ensuring the original evidence is never altered during analysis.

Operational Requirements for Imaging Tools

Research and development of disk imaging tools must prioritize the following operational capabilities to ensure evidence integrity:

- Write-Blocking: Tools must integrate hardware or software write-blockers to prevent any data modification on the source device during acquisition [24].

- Integrity Verification: Tools must generate cryptographic hash values (e.g., MD5, SHA-1, SHA-256) pre- and post-acquisition to verify the evidence has not been altered [24].

- Forensic Image Formats: Support for standard and proprietary formats (e.g., DD/RAW, E01, AFF) is essential, allowing for data compression, authentication, and metadata embedding [25].

- Logging and Documentation: Comprehensive audit trails documenting the entire acquisition process, including tools used, technicians involved, and timestamps, are mandatory for chain of custody [24].

Protocol: Creating a Forensic Disk Image using FTK Imager

Objective: To create a forensically sound image of a storage device while preserving data integrity and establishing a verifiable chain of custody.

Materials:

- Source storage device (e.g., HDD, SSD)

- Write-blocker (hardware or software)

- Forensic workstation with sufficient storage capacity

- FTK Imager or equivalent tool [25]

- Destination storage media (e.g., external forensic drive)

Methodology:

- Preparation: Connect the source storage device to the forensic workstation via a write-blocking unit. Ensure the destination storage media has adequate free space for the image file [24].

- Launch and Source Selection: Open FTK Imager. Select

File>Create Disk Image. Choose the source drive detected via the write-blocker [25]. - Image Destination and Format: Select the destination folder and name for the image file. Choose a forensic image format (e.g., E01). Provide evidence item details (e.g., case number, examiner) [25].

- Acquisition and Hashing: Initiate the imaging process. FTK Imager will create the image and automatically generate MD5 and SHA1 hash values upon completion [25].

- Verification: Verify that the hash values generated at the conclusion of the process match those displayed before acquisition began. Document this verification [24].

- Chain of Custody: Complete evidence documentation forms, logging the date, time, technician, source device, destination media, and hash values [24].

Research Reagent Solutions: Disk Imaging

Table 1: Essential Tools and Materials for Forensic Disk Imaging

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Hardware Write-Blocker | A hardware device that physically prevents write commands from being sent to the source storage device, protecting evidence integrity [24]. |

| FTK Imager | A software tool for creating forensic images of hard drives and other storage media, supporting multiple output formats [25]. |

| Forensic Workstation | A dedicated computer with multiple interfaces (SATA, USB 3.0) and ample storage for handling large evidence images. |

| Cryptographic Hashing Tool | Software or integrated tool functionality (e.g., within FTK Imager) to generate unique hash values for verifying image authenticity [25]. |

Disk Imaging Workflow

RAM Capture

Live Random Access Memory (RAM) capture is a volatile memory acquisition technique critical for recovering ephemeral data such as running processes, unencrypted passwords, network connections, and memory-resident malware that would be permanently lost upon power loss [25] [26].

Operational Requirements for RAM Capture Tools

Tools designed for RAM capture must fulfill specific operational demands due to the volatile nature of the evidence:

- Minimal Footprint: The acquisition tool must have a minimal memory and processing footprint to avoid altering the very memory space it is attempting to capture [26].

- Speed: Acquisition must be rapid to minimize the risk of data decay and changes in the system's state [26].

- Compatibility: Tools must support a wide range of operating systems and versions to be effective across diverse environments [27].

- Robust Output: The tool must generate a raw memory dump or a compatible format for analysis with frameworks like Volatility [25].

Protocol: Capturing Volatile Memory with FTK Imager

Objective: To acquire a complete dump of the system's volatile memory (RAM) while the system is live, preserving data for subsequent forensic analysis.

Materials:

- A live, powered-on target computer (e.g., Windows 10/11 system)

- FTK Imager installed on the target system (portable version recommended) [25]

- External storage media with sufficient free space (minimum equal to system RAM + page file)

Methodology:

- Preparation: Attach the external storage media to the target system. If possible, run FTK Imager from the external media to minimize contamination of the evidence.

- Initiate Capture: In FTK Imager, navigate to

File>Capture Memory. This opens the memory capture dialog box [25]. - Configure Output: In the capture dialog:

- Select the destination folder on the external storage media.

- Provide a filename for the memory dump (e.g.,

Case001_MemoryDump.mem). - Check the option to

Include pagefile[25].

- Execute Acquisition: Click the

Capture Memorybutton. A progress window will track the acquisition. The time required is proportional to the amount of installed RAM [25]. - Verification and Documentation: Upon completion, FTK Imager generates a log and a .mem file. Note the file size and location. Document the date, time, and system state at the time of capture.

Analysis Protocol: Profiling a Memory Image with Volatility

Objective: To analyze a captured memory image to identify the operating system profile, active processes, and potential malware.

Materials:

Methodology:

- Determine Image Profile: Use Volatility's

imageinfoplugin to identify the correct OS profile for subsequent analysis.- Command:

vol.py -f /path/to/memory.image imageinfo[25]

- Command:

- List Running Processes: Use the

pslistplugin with the identified profile to enumerate active processes at capture time.- Command:

vol.py --profile=[ProfileName] -f /path/to/memory.image pslist[25]

- Command:

- Scan for Malware: Use the

malfindplugin to identify hidden or injected processes and malware.- Command:

vol.py --profile=[ProfileName] -f /path/to/memory.image malfind[25]

- Command:

- Extract Network Information: Use plugins like

netscanto recover network connections and sockets [27].

Research Reagent Solutions: RAM Capture & Analysis

Table 2: Essential Tools and Materials for RAM Capture and Analysis

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| FTK Imager | A widely used tool for capturing live memory (RAM) from a system, creating a .mem file for analysis [25]. |

| Volatility Framework | The premier open-source memory analysis framework, used for in-depth forensic analysis of memory dumps [25] [27]. |

| WinPmem | A specialized, efficient memory acquisition tool for Windows systems, known for its minimal footprint [27]. |

| Redline | A comprehensive memory and file analysis tool from FireEye that allows for in-depth analysis and creation of Indicators of Compromise (IOCs) [27]. |

RAM Capture and Analysis Workflow

Mobile Device Extraction

Mobile device extraction involves acquiring data from smartphones and tablets, a complex domain due to device diversity, proprietary operating systems, and robust hardware encryption [28] [29].

Operational Requirements for Mobile Extraction Tools

The research and development of mobile forensic tools must account for an ecosystem defined by rapid change and high security:

- Methodological Flexibility: Tools must support multiple extraction methods (Logical, File System, Physical) to handle varying device states and security levels [30] [28].

- Cloud and App Data Focus: With the increasing use of encrypted storage and cloud-synchronized applications, tools must evolve to extract and decode data from a vast array of apps and cloud backups [8] [29].

- Remote Acquisition Capability: To address logistical challenges, tools should support secure remote collection from devices across multiple geographic locations [30].

- AI-Powered Analysis: Given the data volume, tools must incorporate AI and automation to efficiently parse and analyze extracted data [29].

Protocol: Logical and File System Extraction of a Mobile Device

Objective: To extract active data and, where possible, file system data from a mobile device using forensic tools.

Materials:

- Mobile device (smartphone/tablet)

- Forensic workstation with mobile extraction software (e.g., Cellebrite UFED, Oxygen Forensics, Magnet AXIOM) [8] [28]

- Appropriate USB cables

- Faraday bag or box to isolate the device from networks (optional, to prevent remote wipe) [28]

Methodology:

- Device Isolation and Documentation: Place the device in a Faraday bag to block cellular and Wi-Fi signals. Photograph the device's physical state and note its make, model, and IMEI number [28].

- Connection and Tool Selection: Connect the device to the forensic workstation. Launch the extraction tool and select the appropriate extraction type based on device compatibility and investigative needs [30]:

- Logical Extraction: Extracts active data accessible through the device's API (e.g., contacts, messages, call logs). This is the fastest and most widely supported method [30].

- File System Extraction: Gains deeper access to the device's internal memory, including some system files and potentially deleted data. This requires root (Android) or jailbreak (iOS) access on many devices [30] [28].

- Execution and Data Parsing: Initiate the extraction. The tool will communicate with the device and extract the selected data, often parsing it into a human-readable format (e.g., reports, timelines).

- Verification and Reporting: The tool typically generates a hash of the extracted data. Review the extracted data and generate a report for analysis [30].

Research Reagent Solutions: Mobile Device Extraction

Table 3: Essential Tools and Methods for Mobile Device Extraction

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Cellebrite UFED | A leading mobile forensic tool capable of logical, file system, and physical extraction from a wide range of mobile devices, including cloud data extraction [8]. |

| Oxygen Forensics Detective | Advanced mobile forensics software specializing in extracting and decoding data from smartphones, IoT devices, and cloud services [29]. |

| Magnet AXIOM | A digital forensics platform with strong capabilities in mobile and cloud evidence acquisition and analysis [8]. |

| Faraday Bag/Box | A shielded container that blocks radio signals (cellular, Wi-Fi, Bluetooth), preventing remote data alteration or wipe during seizure and acquisition [28]. |

Mobile Device Extraction Workflow

Digital evidence forms the backbone of modern criminal and corporate investigations, yet its fragile nature necessitates rigorous preservation techniques to maintain legal admissibility [1]. Unlike physical evidence, digital data can be easily altered, deleted, or corrupted through normal system processes or inadvertent handling [1]. Within this framework, two technologies serve as fundamental pillars for ensuring evidence integrity: write blockers, which prevent modification of original evidence during acquisition, and cryptographic hashing, which provides verifiable proof of integrity throughout the evidence lifecycle [31] [32]. This document outlines the operational protocols and technical standards for implementing these critical tools within digital evidence acquisition workflows, providing researchers and forensic practitioners with validated methodologies for maintaining chain-of-custody integrity.

Technical Foundation

Write Blockers: Hardware and Software Implementations

Write blockers are specialized tools that create a read-only interface between a forensic workstation and digital storage media, intercepting and blocking any commands that would modify the original evidence [31] [33].

Core Principles of Operation:

- Intercept all write commands at the interface level before they reach the storage media

- Allow uninterrupted read commands for data acquisition

- Maintain a complete audit trail of access operations

- Provide physical or logical indicators of write-blocking status [31] [34]

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Write Blocker Types

| Characteristic | Hardware Write Blocker | Software Write Blocker |

|---|---|---|

| Implementation | Physical device between computer and storage media [31] | Software application installed on forensic computer [31] |

| Reliability | Higher reliability, less prone to OS/software conflicts [31] | Dependent on host OS stability and configuration [31] |

| Cost Factor | Higher initial investment [31] [35] | More budget-friendly [31] |

| Deployment Flexibility | Limited to physical connectivity [31] | Highly flexible, quickly deployed across systems [31] |

| Preferred Use Cases | High-stakes investigations requiring absolute data integrity [31] | Scenarios where hardware is impractical; virtual environments [31] |

Cryptographic Hashing: Algorithms and Applications

Cryptographic hashing generates a unique digital fingerprint of data through mathematical algorithms that produce a fixed-length string of characters representing the contents of a file or storage medium [32] [36].

Fundamental Characteristics of Hash Values:

- Deterministic: A specific input always produces the same hash value [32]

- Avalanche Effect: Minimal changes to input create dramatically different hashes [32]

- Unidirectional: Computationally infeasible to reverse the process [32] [36]

- Collision Resistant: Extremely low probability of two different inputs producing identical hashes [32]

Table 2: Evolution of Hashing Algorithms in Digital Forensics

| Algorithm | Hash Length | Security Status | Recommended Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| MD5 | 128 bits | Vulnerable to collision attacks; considered obsolete for security [37] | Legacy verification only [37] |

| SHA-1 | 160 bits | Cryptographically broken; susceptible to deliberate attacks [32] [37] | Legacy systems where risk is acceptable [37] |

| SHA-256 | 256 bits | Secure; current standard for forensic applications [32] [35] | All new forensic investigations [32] [35] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Write Blocker Validation Protocol

Objective: Verify that write blocking hardware/software effectively prevents all write commands from reaching protected storage media while maintaining complete data accessibility.

Materials:

- Device Under Test (DUT): Hardware write blocker or software write blocking application

- Forensic workstation with approved forensic software (FTK Imager, EnCase, X-Ways)

- Test storage media (HDD, SSD, flash media)

- Write detection software or hardware analyzers

Procedure:

- Pre-Test Configuration

- Connect DUT between forensic workstation and test media

- Document initial state of test media, including directory structure and timestamps

- Generate baseline hash values for all test media sectors

Write Command Testing

- Attempt direct write operations to protected media via operating system

- Use forensic tools to attempt modification of metadata structures

- Test file creation, deletion, and modification commands

- Verify that all write attempts are blocked and generate error logs

Read Accessibility Verification

- Conduct complete sector-by-sector read of protected media

- Verify file system accessibility and directory navigation

- Confirm that all data remains accessible through forensic tools

Validation Reporting

- Document all test procedures and results

- Compare post-test hash values with baseline measurements

- Certify device for forensic use only if zero write operations are detected

Forensic Imaging with Hash Verification Protocol

Objective: Create a forensically sound duplicate of original evidence media while generating cryptographic verification of integrity.

Materials:

- Validated write blocking solution (hardware preferred)

- Forensic imaging equipment (Tableau TX/TD series, Logicube, etc.)

- Target storage media with sufficient capacity

- Hash calculation software (integrated or standalone)

Procedure:

- Evidence Preparation

- Document original evidence condition and identifiers

- Connect evidence media to write blocker, then to imaging system

- Verify write blocker status indicators show active protection

Forensic Image Creation

- Configure imaging software for sector-by-sector acquisition

- Select destination media with sufficient storage capacity

- Enable integrated hashing during acquisition process

- Monitor imaging process for errors or read failures

Hash Verification Process

- Generate hash of original media post-imaging (if possible)

- Calculate hash of forensic image using multiple algorithms (SHA-256 mandatory)

- Compare hash values from source and image

- Document verification in evidence log

Quality Assurance

- Verify forensic image mounts correctly in analysis tools

- Confirm file system integrity and accessibility

- Generate final certification of forensic soundness

Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Digital Forensics Laboratory Equipment

| Equipment Category | Example Products | Primary Function | Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hardware Write Blockers | Tableau Forensic Bridges, WiebeTech WriteBlocker, SalvationDATA DK2 [31] [35] [33] | Physical prevention of write commands to evidence media [31] | Multi-interface support (SATA, IDE, SAS, PCIe, USB); LED status indicators; read-only mode enforcement [34] |

| Forensic Imagers/Duplicators | OpenText TX2/TD4 Series, Logicube Falcon [34] [38] | Create forensically sound copies of evidence media [34] [38] | High-speed imaging; integrated hashing; touch-screen interfaces; portable form factors [34] |

| Software Write Blockers | SAFE Block, Forensic Software Utilities [35] | Logical write protection through OS-level controls [31] | Operating system integration; configuration flexibility; audit logging |

| Hash Verification Tools | FTK Imager, Toolsley Online Hash Generator [32] [35] | Generate and compare cryptographic hash values [32] [35] | Support for multiple algorithms (MD5, SHA-1, SHA-256); batch processing; integration with forensic workflows |

Data Integrity Verification Framework

Hash Value Implementation in Evidence Management

Cryptographic hashing provides a mathematical foundation for demonstrating evidence integrity from acquisition through courtroom presentation [32] [35].

Legal Recognition: Federal Rules of Evidence 902(13) and (14) establish that electronic evidence authenticated through hash verification can be admitted without requiring sponsoring witness testimony, provided proper certification is presented [32]. Judicial systems internationally have recognized hash values as scientifically valid methods for authenticating digital evidence, with courts in the United States, United Kingdom, and India consistently accepting hash-verified evidence [35].

Integration with Chain of Custody Protocols

Hash verification must be integrated with comprehensive chain of custody documentation to create a legally defensible evidence management system [35] [39].

Documentation Requirements:

- Record all hash values generated during evidence lifecycle

- Document specific algorithms used for hash generation

- Log all personnel handling evidence and verification timestamps

- Maintain audit trail of all integrity verification checks

Write blockers and cryptographic hashing represent non-negotiable technical requirements for digital evidence acquisition in forensic investigations. The protocols outlined in this document provide researchers and practitioners with standardized methodologies for implementing these critical integrity preservation tools. As digital evidence continues to evolve in complexity and volume, maintaining rigorous adherence to these fundamental principles ensures the continued legal admissibility and scientific validity of digital forensic investigations. Future research directions should focus on automated integrity verification systems, blockchain-based chain of custody applications, and enhanced write blocking technologies for emerging storage media formats.

Maintaining a Defensible Chain of Custody with Automated Audit Logging

For researchers and scientists, particularly in regulated fields like drug development, the integrity of digital data generated by analytical instruments and software is paramount. The chain of custody—the chronological, tamper-evident documentation of every action performed on a piece of digital evidence—is a foundational component of data integrity. In a regulatory context, a defensible chain of custody is non-negotiable for proving due diligence and the authenticity of scientific data during audits or legal proceedings [40] [41].

Traditional, manual methods of evidence logging, such as paper trails or spreadsheets, are inherently fragile. They are vulnerable to human error, inadvertent modifications, and gaps in documentation that can compromise an entire dataset's admissibility [40]. Automated audit logging represents the modern standard, creating an immutable, system-generated record of every interaction with digital evidence. This protocol outlines the operational requirements and implementation frameworks for integrating automated audit logging into digital evidence acquisition tools, ensuring generated data meets the rigorous standards of scientific and legal scrutiny.

Core Principles of a Defensible Digital Chain of Custody

An automated system must be architected upon three bedrock principles to ensure the defensibility of the digital chain of custody.