Empirical Validation in Forensic Text Comparison: Requirements, Methods, and Future Directions

This article provides a comprehensive examination of the empirical validation requirements for forensic text comparison (FTC), a discipline increasingly critical for authorship analysis in legal contexts.

Empirical Validation in Forensic Text Comparison: Requirements, Methods, and Future Directions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of the empirical validation requirements for forensic text comparison (FTC), a discipline increasingly critical for authorship analysis in legal contexts. It explores the foundational shift towards a scientific framework based on quantitative measurements, statistical models, and the likelihood-ratio framework. The content details methodological pipelines for calculating and calibrating likelihood ratios, addresses key challenges such as topic mismatch and data relevance, and establishes validation criteria and performance metrics essential for demonstrating reliability. Aimed at forensic scientists, linguists, and legal professionals, this guide synthesizes current research to outline a path toward scientifically defensible and legally admissible forensic text analysis.

The Scientific Foundation for Valid Forensic Text Comparison

Forensic science stands at a crossroads. For decades, widespread practice across most forensic disciplines has relied on analytical methods based on human perception and interpretive methods based on subjective judgement [1]. These approaches are inherently non-transparent, susceptible to cognitive bias, often logically flawed, and frequently lack empirical validation [1]. This status quo has contributed to documented errors, with the misapplication of forensic science being a contributing factor in 45% of wrongful convictions later overturned by DNA evidence [2]. In response, a profound paradigm shift is underway, moving forensic science toward methods grounded in relevant data, quantitative measurements, and statistical models that are transparent, reproducible, and intrinsically resistant to cognitive bias [1].

This transformation is particularly crucial for forensic text comparison research, where the limitations of subjective assessment can directly impact legal outcomes. The new paradigm emphasizes the likelihood-ratio framework as the logically correct method for interpreting evidence and requires empirical validation under casework conditions [1]. This shift represents nothing less than a fundamental reimagining of forensic practice, replacing "untested assumptions and semi-informed guesswork with a sound scientific foundation and justifiable protocols" [1].

The Current Paradigm: Limitations and Criticisms

The Status Quo in Forensic Practice

The current state of forensic science, particularly in pattern evidence disciplines such as fingerprints, toolmarks, and handwriting analysis, has been described by the UK House of Lords Science and Technology Select Committee as employing "spot-the-difference" techniques with "little, if any, robust science involved in the analytical or comparative processes" [1]. These methods raise significant concerns about reproducibility, repeatability, accuracy, and error rates [1]. The fundamental process involves two stages: analysis (extracting information from evidence) and interpretation (drawing inferences about that information) [1]. In the traditional model, both stages depend heavily on human expertise rather than objective measurement.

Specific Vulnerabilities of Traditional Methods

- Susceptibility to Cognitive Bias: Forensic practitioners are vulnerable to subconscious cognitive biases when making perceptual observations and subjective judgements [1]. This bias can occur when examiners are exposed to contextual information that influences their degree of belief in a hypothesis without logically affecting the probability of the evidence [1].

- Logical Fallacies in Interpretation: Traditional interpretation often relies on logically flawed reasoning, including the "uniqueness or individualization fallacy," where examiners may overstate the significance of similar features [1]. Conclusions are often expressed categorically (e.g., "identification," "exclusion") or using uncalibrated verbal scales that lack empirical foundation [1].

- Non-Transparent Processes: Methods dependent on human perception and subjective judgement are intrinsically non-transparent and not reproducible by others [1]. Human introspection is often mistaken, meaning a practitioner's explanation of their reasoning may not accurately reflect how they reached their conclusion [1].

Table 1: Limitations of Traditional Forensic Science Approaches

| Aspect | Current Practice | Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Method | Human perception | Non-transparent, variable between examiners |

| Interpretive Framework | Subjective judgement | Susceptible to cognitive bias |

| Logical Foundation | Individualization fallacy | Logically flawed conclusions |

| Validation | Often lacking | Unestablished error rates |

The Emerging Paradigm: Principles and Framework

Core Components of the New Approach

The paradigm shift in forensic evidence evaluation replaces subjective methods with approaches based on relevant data, quantitative measurements, and statistical models or machine-learning algorithms [1]. These methods share several critical characteristics that address the shortcomings of traditional practice:

- Transparency and Reproducibility: Unlike human-dependent methods, approaches based on quantitative measurement and statistical modeling can be described in detail, with data and software tools potentially shared for verification and replication [1].

- Resistance to Cognitive Bias: While subjective decisions remain in system design and validation, these occur before analyzing specific case evidence, and the subsequent automated evaluation process is not susceptible to the cognitive biases that affect human examiners [1].

- Empirical Validation: The new paradigm requires that forensic evaluation systems be empirically validated under casework conditions, providing measurable performance metrics and error rates rather than relying on practitioner experience alone [1].

The Likelihood-Ratio Framework

The likelihood-ratio framework is advocated as the logically correct framework for evidence evaluation by the vast majority of experts in forensic inference and statistics, and by key organizations including the Royal Statistical Society, European Network of Forensic Science Institutes, and the American Statistical Association [1]. This framework requires assessing:

The probability of obtaining the evidence if one hypothesis were true versus the probability of obtaining the evidence if an alternative hypothesis were true [1].

This approach quantifies the strength of evidence rather than making categorical claims about source, properly accounting for both the similarity between samples and their rarity in the relevant population.

Diagram 1: Likelihood Ratio Framework

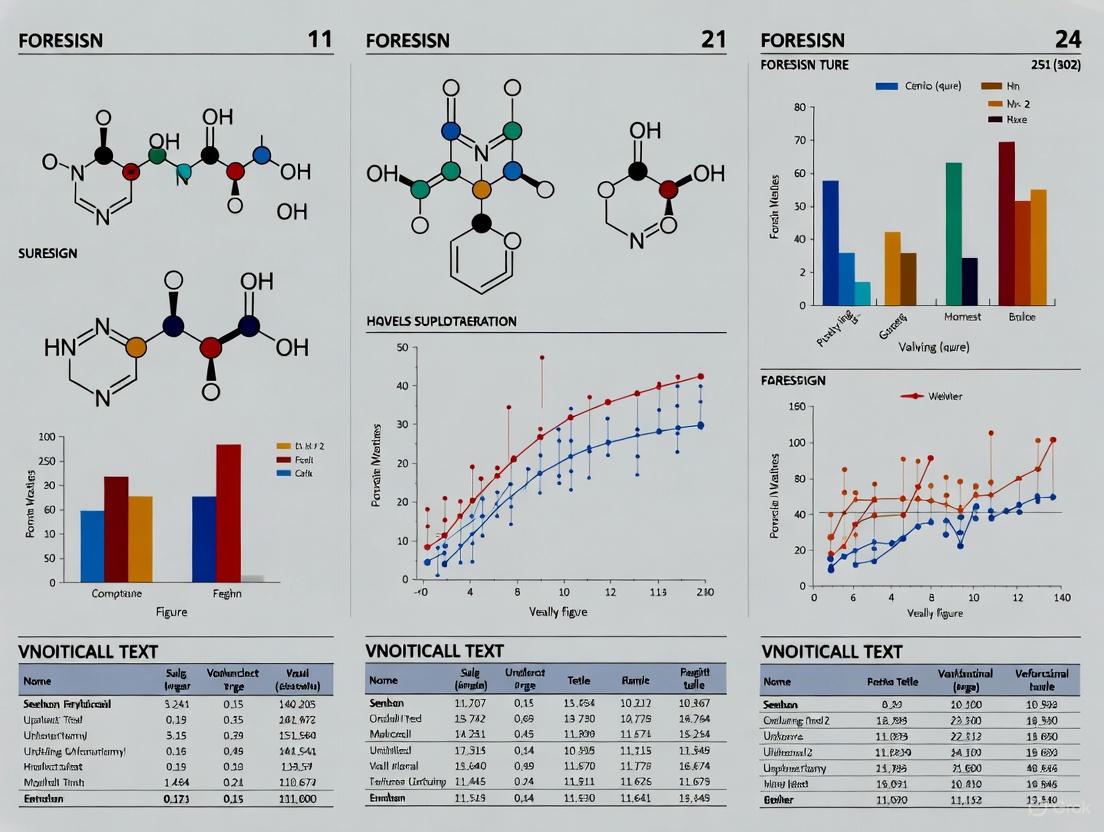

Empirical Comparison: Score-Based vs. Feature-Based Methods

Experimental Design and Methodology

A comprehensive empirical study comparing score-based and feature-based methods for estimating forensic likelihood ratios for text evidence provides valuable insights into the practical implementation of the new paradigm [3]. The research utilized:

- Data Source: Documents attributable to 2,157 authors [3]

- Feature Set: A bag-of-words model using the 400 most frequently occurring words [3]

- Compared Methods:

- Score-based method: Employed cosine distance as a score-generating function

- Feature-based methods: Three Poisson-based models with logistic regression fusion:

- One-level Poisson model

- One-level zero-inflated Poisson model

- Two-level Poisson-gamma model

- Evaluation Metrics: Log-likelihood ratio cost (Cllr) and its components for discrimination (Cllrmin) and calibration (Cllrcal) [3]

Quantitative Results and Performance Comparison

The experimental results demonstrated clear performance differences between the methodological approaches:

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Forensic Text Comparison Methods

| Method Type | Specific Model | Performance (Cllr) | Relative Advantage | Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Score-Based | Cosine distance | Baseline | - | Simple implementation |

| Feature-Based | One-level Poisson | 0.14-0.20 improvement | Better calibration | Handles count data |

| Feature-Based | Zero-inflated Poisson | 0.14-0.20 improvement | Superior with sparse data | Accounts for excess zeros |

| Feature-Based | Poisson-gamma | 0.14-0.20 improvement | Best overall performance | Captures overdispersion |

The findings revealed that feature-based methods outperformed the score-based method by a Cllr value of 0.14-0.20 when comparing their best results [3]. Additionally, the study demonstrated that a feature selection procedure could further enhance performance for feature-based methods [3]. These results have significant implications for real forensic casework, suggesting that feature-based approaches provide more statistically sound foundations for evaluating text evidence.

Implementation Framework: Transitioning to the New Paradigm

Experimental Protocols for Forensic Text Comparison

Implementing the new paradigm requires rigorous experimental protocols. For forensic text comparison, this involves:

- Data Collection and Curation: Assembling representative text corpora with known authorship, sufficient in size (thousands of authors) to support robust model development and validation [3].

- Feature Engineering: Selecting and extracting relevant linguistic features, such as the 400 most frequently occurring words in bag-of-words models, with procedures for feature selection to optimize performance [3].

- Model Development and Training: Constructing statistical models (e.g., Poisson-based models for text data) that can quantify the strength of evidence using the likelihood-ratio framework [3].

- Validation and Performance Assessment: Rigorously evaluating systems using appropriate metrics like log-likelihood ratio cost (Cllr) and its components to assess both discrimination and calibration under casework-like conditions [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Methodological Components for Empirical Forensic Validation

| Component | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software Platforms | Provide computational environment for quantitative analysis | R, Python with specialized forensic packages |

| Likelihood Ratio Framework | Logically correct structure for evidence evaluation | Calculating probability ratios under competing hypotheses [1] |

| Validation Metrics | Quantify system performance and reliability | Cllr, Cllrmin, Cllrcal for discrimination and calibration [3] |

| Reference Data Corpora | Enable empirical measurement of feature distributions | Collection of 2,157 authors' documents for text analysis [3] |

| Feature Extraction Algorithms | Convert raw evidence into quantifiable features | Bag-of-words model with 400 most frequent words [3] |

| JK184 | JK184, CAS:315703-52-7, MF:C19H18N4OS, MW:350.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| JS-K | JS-K|NO Donor Prodrug|For Research | JS-K is a GST-activated nitric oxide donor prodrug used in cancer research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. |

Diagram 2: Empirical Validation Workflow

The paradigm shift from subjective judgment to empirical validation represents forensic science's maturation as a rigorously scientific discipline. This transition addresses fundamental limitations of traditional practice by implementing transparent, quantitative methods based on statistical principles rather than human intuition alone. The empirical comparison of forensic text evaluation methods demonstrates that feature-based approaches outperform score-based methods, providing a more statistically sound foundation for evidence evaluation [3].

As the field continues this transformation, implementation of the likelihood-ratio framework and rigorous empirical validation will be critical [1]. This shift requires building statistically sound and scientifically solid foundations for forensic evidence analysis—a challenging but essential endeavor for ensuring the reliability and validity of forensic science in the justice system [2]. The pathway forward is clear: replacing antiquated assumptions of uniqueness and perfection with defensible empirical and probabilistic foundations [1].

The analysis and interpretation of forensic textual evidence have entered a new era of scientific scrutiny. There is increasing consensus that a scientifically defensible approach to Forensic Text Comparison (FTC) must be built upon a core set of empirical elements to ensure transparency, reproducibility, and resistance to cognitive bias [4]. This shift is driven by the understanding that textual evidence is complex, encoding not only information about authorship but also about the author's social background and the specific communicative situation, including genre, topic, and level of formality [4]. This guide objectively compares the core methodologies—quantitative measurements, statistical models, and the Likelihood-Ratio (LR) framework—that constitute a modern scientific FTC framework, situating the comparison within the critical context of empirical validation requirements for forensic text comparison research.

Core Framework Elements: A Comparative Analysis

The following section provides a detailed, side-by-side comparison of the three foundational elements that constitute a scientific FTC framework. The table below summarizes their defining characteristics, primary functions, and their role in ensuring empirical validation.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Core Elements in a Scientific FTC Framework

| Framework Element | Core Definition & Function | Role in Empirical Validation | Key Considerations for Researchers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative Measurements | The process of converting textual characteristics into numerical data [4]. It provides an objective basis for analysis, moving beyond subjective opinion. | Enables the transparent and reproducible collection of data. Forms the empirical basis for all subsequent statistical testing and validation studies [4]. | Selection of features (e.g., lexical, syntactic, character-based) must be justified and relevant to case conditions. Measurements must be consistent across compared documents. |

| Statistical Models | Mathematical structures that use quantitative data to calculate the probability of observing the evidence under different assumptions [4]. | Provides a structured and testable method for evidence interpretation. Models themselves must be validated on relevant data to demonstrate reliability [4]. | The choice of model (e.g., Dirichlet-multinomial) impacts performance. Models must be robust to real-world challenges like topic mismatch between documents. |

| Likelihood-Ratio (LR) Framework | A logical framework for evaluating the strength of evidence by comparing the probability of the evidence under two competing hypotheses [4]. | Offers a coherent and logically sound method for expressing conclusions. It separates the evaluation of evidence from the prior beliefs of the trier-of-fact, upholding legal boundaries [4]. | Proper implementation requires relevant background data to estimate the probability of the evidence under the defense hypothesis (p(E|H_d)). |

Experimental Protocols for Validated FTC Research

For research and development in forensic text comparison to be scientifically defensible, experimental protocols must be designed to meet two key requirements for empirical validation: 1) reflecting the conditions of the case under investigation, and 2) using data relevant to the case [4]. The following workflow details a robust methodology for conducting validated experiments, using the common challenge of topic mismatch as a case study.

Defining Casework Conditions and Data Collection

The first step is to define the specific condition for which the methodology requires validation. In our example, this is a mismatch in topics between the questioned and known documents, a known challenging factor in authorship analysis [4].

- Define the Mismatch Type: Researchers must explicitly define the nature of the topic mismatch (e.g., sports journalism vs. technical manuals, or informal blogs vs. formal reports).

- Source Relevant Data: The experimental database must be constructed from text sources that accurately reflect this defined mismatch. Using data with a uniform topic invalidates the experiment's purpose. Data should be sourced from genuine text corpora that mirror the anticipated real-world conditions [4].

Quantitative Feature Extraction and Statistical Modeling

This phase transforms raw text into analyzable data and applies a statistical model.

- Feature Extraction: Convert the collected texts into quantitative measurements. The specific features (e.g., vocabulary richness, character n-grams, function word frequencies, syntactic markers) should be selected and extracted consistently across all documents [4].

- Model Calculation: Employ a statistical model to compute the probability of the evidence. For instance, a Dirichlet-multinomial model can be used to calculate the likelihood of the quantitative measurements from the questioned document, given the known author's writing style, and the likelihood given the writing style of other authors in a relevant population [4].

- The output is a Likelihood Ratio (LR), expressed as: ( LR = \frac{p(E|Hp)}{p(E|Hd)} ) where (Hp) is the prosecution hypothesis (same author) and (Hd) is the defense hypothesis (different authors) [4].

Calibration, Assessment, and Reporting

The final phase involves validating the system's performance.

- Logistic Regression Calibration: The raw LRs generated by the model often require calibration to improve their accuracy and interpretability. Logistic regression is a standard technique for this post-processing step [4].

- Performance Assessment: The calibrated LRs are assessed using objective metrics. A key metric is the log-likelihood-ratio cost (Cllr), which measures the overall performance of the system, penalizing both misleading and misleading LRs [4].

- Visualization with Tippett Plots: Results are often visualized using Tippett plots, which graphically display the cumulative distribution of LRs for both same-author and different-author comparisons, providing an intuitive view of the method's discrimination and calibration [4].

- Report Validation Metrics: The final step is to report the Cllr and other relevant metrics, providing a quantitative summary of the empirical validation for the specific casework condition tested.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents for FTC

Implementing a robust FTC framework requires a suite of methodological "reagents." The following table details key components, their functions, and their role in ensuring validated outcomes.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Forensic Text Comparison

| Tool / Reagent | Function in the FTC Workflow | Critical Role in Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Relevant Text Corpora | Serves as the source of known and population data for modeling and testing. | Fundamental. Using irrelevant data (e.g., uniform topics) fails Requirement 2 of validation and misleads on real-world performance [4]. |

| Dirichlet-Multinomial Model | A specific statistical model used for calculating likelihood ratios based on discrete textual features [4]. | Provides a testable and reproducible method for evidence evaluation. Its performance must be empirically assessed under case-specific conditions. |

| Logistic Regression Calibration | A post-processing technique that adjusts the output of the statistical model to produce better calibrated LRs [4]. | Directly addresses empirical performance. It corrects for over/under-confidence in the raw model outputs, leading to more accurate LRs. |

| Log-Likelihood-Ratio Cost (Cllr) | A single numerical metric that summarizes the overall performance of a LR-based system [4]. | Provides an objective measure of validity. A lower Cllr indicates better system performance, allowing for comparison between different methodologies. |

| Tippett Plot | A graphical tool showing the cumulative proportion of LRs for both same-source and different-source propositions [4]. | Enables visual validation of system discrimination and calibration, showing how well the method separates true from non-true hypotheses. |

| (Iso)-Z-VAD(OMe)-FMK | (Iso)-Z-VAD(OMe)-FMK, CAS:821794-92-7, MF:C18H19FN4O2, MW:342.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| KFM19 | KFM19 Adenosine A1 Receptor Antagonist | KFM19 is a selective adenosine A1 receptor antagonist for neuroscience research. It is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

The movement towards a fully empirical foundation for forensic text comparison is unequivocal. As this guide has demonstrated, the triad of quantitative measurements, statistical models, and the likelihood-ratio framework provides the necessary structure for developing scientifically defensible methods. However, the mere use of these tools is insufficient. Their power is unlocked only through rigorous empirical validation that replicates real-world case conditions, such as topic mismatch, and utilizes relevant data [4]. For researchers and scientists in this field, the ongoing challenge and opportunity lie in defining the specific casework conditions that require validation, determining what constitutes truly relevant data, and establishing the necessary quality and quantity of that data to underpin demonstrably reliable forensic text comparison.

The Likelihood Ratio (LR) has emerged as a cornerstone of modern forensic science, providing a robust statistical framework for evaluating evidence that is both logically sound and legally defensible. Rooted in Bayesian statistics, the LR transforms forensic interpretation from a qualitative assessment to a quantitative science by measuring the strength of evidence under two competing propositions. This framework is particularly crucial in fields such as DNA analysis, fingerprint comparison, and forensic text analysis, where empirical validation is essential for maintaining scientific rigor and judicial integrity.

At its core, the LR framework forces forensic scientists to remain within their proper role: evaluating the evidence itself rather than pronouncing on ultimate issues like guilt or innocence. By comparing the probability of observing the evidence under the prosecution's hypothesis versus the defense's hypothesis, the LR provides a balanced, transparent, and scientifically defensible measure of evidential weight. This approach has become increasingly important as courts demand more rigorous statistical validation of forensic methods and as evidence types become more complex, requiring sophisticated interpretation methods beyond simple "match/no-match" declarations.

Theoretical Foundations and Bayesian Framework

The Mathematical Formulation of the Likelihood Ratio

The Likelihood Ratio operates through a deceptively simple yet profoundly powerful mathematical formula that compares two mutually exclusive hypotheses:

LR = P(E|Hp) / P(E|Hd)

Where:

- E represents the observed evidence (e.g., a DNA profile, fingerprint, or text sample)

- P(E|Hp) is the probability of observing the evidence given that the prosecution's hypothesis (Hp) is true

- P(E|Hd) is the probability of observing the evidence given that the defense's hypothesis (Hd) is true [5]

This formula serves as the critical link in Bayes' Theorem, which provides the mathematical foundation for updating beliefs in light of new evidence. The theorem can be expressed as:

Posterior Odds = Likelihood Ratio × Prior Odds

In this equation, the Prior Odds represent the odds of a proposition before considering the forensic evidence, while the Posterior Odds represent the updated odds after considering the evidence. The Likelihood Ratio acts as the multiplier that tells us how much the new evidence should shift our belief from the prior to the posterior state [5]. This relationship underscores why the LR is so valuable: it quantitatively expresses the strength of evidence without requiring forensic scientists to make judgments about prior probabilities, which properly belong to the trier of fact.

Interpreting Likelihood Ratio Values

The numerical value of the LR provides a clear, quantitative measure of evidential strength:

- LR > 1: Supports the prosecution's hypothesis (Hp)

- LR < 1: Supports the defense's hypothesis (Hd)

- LR = 1: The evidence is uninformative; it does not support either hypothesis over the other [5]

The magnitude of the LR indicates the degree of support. For example, an LR of 10,000 means the evidence is 10,000 times more likely to be observed if the prosecution's hypothesis is true than if the defense's hypothesis is true. This scale provides fact-finders with a transparent, numerical basis for assessing forensic evidence rather than relying on potentially misleading verbal descriptions.

Table 1: Interpretation of Likelihood Ratio Values

| LR Value | Strength of Evidence | Direction of Support |

|---|---|---|

| >10,000 | Very Strong | Supports Hp |

| 1,000-10,000 | Strong | Supports Hp |

| 100-1,000 | Moderately Strong | Supports Hp |

| 10-100 | Moderate | Supports Hp |

| 1-10 | Limited | Supports Hp |

| 1 | No support | Neither hypothesis |

| 0.1-1.0 | Limited | Supports Hd |

| 0.01-0.1 | Moderate | Supports Hd |

| 0.0001-0.01 | Strong | Supports Hd |

| <0.0001 | Very Strong | Supports Hd |

LR Validation Protocol and Performance Metrics

A Guideline for Validating LR Methods

The validation of Likelihood Ratio methods used for forensic evidence evaluation requires a systematic protocol to ensure reliability and reproducibility. A comprehensive guideline proposes validation criteria specifically designed for forensic evaluation methods operating within the LR framework [6]. This protocol addresses critical questions including "which aspects of a forensic evaluation scenario need to be validated?", "what is the role of the LR as part of a decision process?", and "how to deal with uncertainty in the LR calculation?" [6].

The validation strategy adapts concepts typical for validation standards—such as performance characteristics, performance metrics, and validation criteria—to the LR framework. This adaptation is essential for accreditation purposes and for ensuring that LR methods meet the rigorous standards required in forensic science and legal proceedings. The guideline further describes specific validation methods and proposes a structured validation protocol complete with an example validation report that can be applied across various forensic fields developing and validating LR methods [6].

Performance Metrics for LR Systems

The performance of LR-based forensic systems is typically evaluated using specific metrics derived from statistical learning theory. Two key metrics borrowed from binary classification are:

- Detection Rate (True Positive Rate): The probability that the system correctly identifies a true match

- False Alarm Rate (False Positive Rate): The probability that the system incorrectly declares a match when no true match exists [7]

These metrics are visualized through the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve, which plots the detection rate against the false alarm rate as the decision threshold varies. The Area Under the ROC (AUROC) quantifies the overall performance of the system, with values closer to 1 indicating excellent discrimination ability and values near 0.5 indicating performance no better than chance [7].

Table 2: Performance Metrics for LR System Validation

| Metric | Definition | Interpretation | Ideal Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Detection Rate | Probability of correct identification when Hp is true | Higher values indicate better sensitivity | 1.0 |

| False Alarm Rate | Probability of incorrect identification when Hd is true | Lower values indicate better specificity | 0.0 |

| AUROC | Area Under Receiver Operating Characteristic curve | Overall measure of discrimination ability | 1.0 |

| Precision | Conditional probability of Hp given a positive declaration | Depends on prior probabilities | Context-dependent |

| Misclassification Rate | Overall probability of incorrect decisions | Weighted average of error types | 0.0 |

Applied Methodologies: Experimental Protocols

DNA Analysis Workflow Using LR Framework

The application of the LR framework to forensic DNA analysis follows a rigorous multi-stage process that combines laboratory techniques with statistical modeling:

Evidence Collection and DNA Profiling: Biological material collected from crime scenes undergoes DNA extraction, quantification, and amplification using Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR). The analysis focuses on Short Tandem Repeats (STRs)—highly variable DNA regions that differ substantially between individuals. The resulting DNA profile is visualized as an electropherogram showing alleles at each STR locus [5].

Hypothesis Formulation: The analyst defines two competing hypotheses:

- Prosecution Hypothesis (Hp): The DNA evidence came from the suspect

- Defense Hypothesis (Hd): The DNA evidence came from an unknown, unrelated individual [5]

Probability Calculation:

- P(E|Hp): Typically close to 1 for single-source samples, assuming the suspect is truly the source and accounting for minor technical variations

- P(E|Hd): Calculated using population genetic databases and the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium principle, resulting in the Random Match Probability (RMP) [5]

LR Determination and Interpretation: The ratio of these probabilities produces the LR, which is then reported with a clear statement such as: "The DNA evidence is X times more likely to be observed if the suspect is the source than if an unknown, unrelated individual is the source." [5]

Figure 1: DNA Analysis Workflow Using LR Framework

Likelihood Ratio Test for Signal Detection in Pharmacovigilance

The LR framework extends beyond traditional forensic domains into pharmaceutical research, where the Likelihood Ratio Test (LRT)-based method serves as a powerful tool for signal detection in drug safety monitoring. This methodology addresses limitations of traditional approaches in analyzing the FDA's Adverse Event Reporting System (AERS) database [8].

The LRT-based method enables researchers to:

- Identify drug-event combinations with disproportionately high frequencies

- Detect signals involving entire drug classes or groups of adverse events simultaneously

- Control Type I error and minimize false discovery rates

- Analyze signal patterns across different time periods [8]

This application demonstrates the versatility of the LR framework across different domains requiring rigorous evidence evaluation, from forensic science to pharmacovigilance. The method's ability to control error rates while detecting complex patterns makes it particularly valuable for monitoring drug safety in large-scale databases where traditional methods might produce excessive false positives.

Advanced Applications: Probabilistic Genotyping

Addressing Complex DNA Evidence

While the basic LR framework works well for single-source DNA samples, modern forensic evidence often presents greater challenges, including:

- Complex DNA mixtures from multiple contributors

- Low-template or degraded DNA samples

- Overlapping alleles that cannot be cleanly separated

For such challenging evidence, probabilistic genotyping software (PGS) becomes essential. PGS uses sophisticated computer algorithms and statistical models (such as Markov Chain Monte Carlo) to evaluate thousands or millions of possible genotype combinations that could explain the observed mixture [5].

Instead of a simple binary comparison, PGS calculates an LR by comparing the probability of observing the mixed DNA evidence if the suspect is a contributor versus if they are not. This approach has revolutionized forensic DNA analysis by providing robust statistical weight to evidence that would have been deemed inconclusive using traditional methods.

Case Study: Sexual Assault Evidence

Consider a sexual assault case where a swab contains a mixture of DNA from the victim and an unknown male contributor:

- Hp: The DNA mixture is from the victim and the suspect

- Hd: The DNA mixture is from the victim and an unknown, unrelated male [5]

Probabilistic genotyping software analyzes how well the suspect's DNA profile fits the mixture compared to random profiles from the population. If the software generates an LR of 500,000, the expert testimony would state: "The mixed DNA profile is 500,000 times more likely if the sample originated from the victim and the suspect than if it originated from the victim and an unknown, unrelated male." [5]

This powerful, quantitative statement provides juries with a clear measure of evidential strength even in complex mixture cases, demonstrating how advanced LR methods extend the reach of forensic science.

Figure 2: Logical Relationships in the LR Framework

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for LR-Based Forensic Research

| Research Reagent | Function | Application Context | |

|---|---|---|---|

| STR Multiplex Kits | Simultaneous amplification of multiple Short Tandem Repeat loci | DNA profiling for human identification | |

| Population Genetic Databases | Provide allele frequency estimates for RMP calculation | Calculating P(E | Hd) for DNA evidence |

| Probabilistic Genotyping Software | Statistical analysis of complex DNA mixtures | Interpreting multi-contributor samples | |

| Quality Control Standards | Ensure reproducibility and accuracy of laboratory results | Validation of forensic methods | |

| Color Contrast Analyzers | Ensure accessibility of data visualizations | Creating compliant diagrams and charts [9] | |

| Statistical Reference Materials | Provide foundation for probability calculations | Training and method validation | |

| Liral | Liral, CAS:31906-04-4, MF:C13H22O2, MW:210.31 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | |

| FSB | FSB, CAS:760988-03-2, MF:C24H17FO6, MW:420.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Comparative Analysis of LR Applications

Table 4: LR Framework Applications Across Domains

| Domain | Evidence Type | Competing Hypotheses | Calculation Method | Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forensic DNA | STR profiles, mixtures | Common vs different source | Population genetics, probabilistic genotyping | High discriminative power, well-established databases |

| Forensic Text | Writing style, linguistic features | Common vs different author | Machine learning, feature comparison | Applicable to digital evidence, continuous evolution |

| Pharmacovigilance | Drug-event combinations | Causal vs non-causal relationship | Likelihood Ratio Test (LRT) | Controls false discovery rates, detects class effects |

| Biometric Authentication | Fingerprints, facial features | Genuine vs imposter | Pattern recognition, statistical models | Automated processing, real-time applications |

The Likelihood Ratio framework represents a fundamental shift in forensic science toward more transparent, quantitative, and logically sound evidence evaluation. As forensic disciplines continue to evolve, the LR approach provides a common statistical language that bridges different evidence types, from DNA and fingerprints to digital text and beyond. The ongoing development of probabilistic genotyping methods, validation protocols, and error rate quantification will further strengthen the foundation of forensic practice.

For researchers and drug development professionals, the LR framework offers a rigorous methodology for evaluating evidence across multiple domains. Its ability to control error rates, provide quantitative measures of evidence strength, and adapt to complex data scenarios makes it an indispensable tool in both forensic science and pharmaceutical research. As the demand for empirical validation increases across scientific disciplines, the LR framework stands as a model for logically and legally correct evidence evaluation.

Forensic linguistics, the application of linguistic analysis to legal and investigative contexts, has historically operated with a significant scientific deficit: a pervasive lack of empirical validation for its methods and conclusions. For much of its history, the discipline has relied on subjective manual analysis and untested assumptions, leading to courtroom testimony that lacked a rigorous scientific foundation. This gap mirrors a broader crisis in forensic science, where methods developed within police laboratories were routinely admitted in court based on practitioner assurance rather than scientific proof [10]. This admission-by-precedent occurred despite the absence of the large, robust literature needed to support the strong claims of individualization often made by experts [10].

The U.S. Supreme Court's 1993 decision in Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals tasked judges with acting as gatekeepers to ensure the scientific validity of expert testimony. However, courts often struggled to apply these standards to forensic linguistics and other feature-comparison disciplines [10]. A pivotal 2009 National Research Council (NRC) report delivered a stark verdict, finding that "with the exception of nuclear DNA analysis… no forensic method has been rigorously shown to have the capacity to consistently, and with a high degree of certainty, demonstrate a connection between evidence and a specific individual or source" [10]. This conclusion highlighted the critical validation gap that had long existed in forensic linguistics and related fields.

Comparative Analysis: Manual, Score-Based, and Feature-Based Methods

The evolution of forensic text comparison methodologies reveals a trajectory from subjective assessment toward increasingly quantitative and empirically testable approaches. The table below systematically compares the three primary paradigms that have dominated the field.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Forensic Text Comparison Methodologies

| Methodology | Core Approach | Key Features/Measures | Reported Performance | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manual Analysis | Subjective expert assessment of textual features [11] | Interpretation of cultural nuances and contextual subtleties [11] | Superior for nuanced interpretation; accuracy not quantitatively established [11] | Lacks standardization and statistical foundation; vulnerable to cognitive biases [10] |

| Score-Based Methods | Quantifies similarity using distance metrics [12] | Cosine distance, Burrows's Delta [12] | Serves as a foundational step for Likelihood Ratio (LR) estimation [12] | Assesses only similarity, not typicality; violates statistical assumptions of textual data [12] |

| Feature-Based Methods | Uses statistical models on linguistic features [12] | Poisson model for Likelihood Ratio (LR) estimation [12] | Outperforms score-based method (Cllr improvement of ~0.09); improved further with feature selection [12] | Theoretically more appropriate but requires complex implementation and validation [12] |

The transition to computational methods represents a significant step toward empirical validation. Machine learning (ML) algorithms, particularly deep learning and computational stylometry, have been shown to outperform manual methods in processing large datasets rapidly and identifying subtle linguistic patterns, with one review of 77 studies noting a 34% increase in authorship attribution accuracy in ML models [11]. However, this review also cautioned that manual analysis retains superiority in interpreting cultural nuances and contextual subtleties, suggesting the need for hybrid frameworks [11].

Experimental Protocols and Validation Frameworks

The Likelihood Ratio Framework and Poisson Model Implementation

Modern forensic text comparison research has increasingly adopted the Likelihood Ratio (LR) framework as a validation tool. This framework quantifies the strength of evidence by comparing the probability of the evidence under two competing hypotheses: the same author wrote both documents (prosecution hypothesis) versus different authors wrote the documents (defense hypothesis) [12].

A 2020 study by Carne and Ishihara implemented a feature-based method using a Poisson model for LR estimation, comparing it against a traditional score-based method using Cosine distance. The experimental protocol involved:

- Data Collection: Textual data was collected from 2,157 authors to ensure statistical power and representativeness [12].

- Feature Engineering: The researchers extracted and selected linguistic features from the texts, with performance improving through strategic feature selection [12].

- Model Validation: The log-LR cost (Cllr) was used as the primary performance metric to assess the validity and reliability of the computed LRs [12].

This study demonstrated that the feature-based Poisson model outperformed the score-based method, achieving a Cllr improvement of approximately 0.09 under optimal settings [12]. This provides empirical evidence supporting the transition toward more statistically sound methodologies.

A Guidelines Approach to Validation

Inspired by the Bradford Hill Guidelines for causal inference in epidemiology, researchers have proposed a guidelines approach to establish the validity of forensic feature-comparison methods [10]. This framework addresses the unique challenges courts have faced in applying Daubert factors to forensic disciplines.

Table 2: Scientific Guidelines for Validating Forensic Comparison Methods

| Guideline | Core Question | Application to Forensic Linguistics |

|---|---|---|

| Plausibility | Is there a sound theoretical basis for the method? [10] | Requires establishing that writing style contains sufficiently unique and consistent features for discrimination. |

| Research Design Validity | Are the research methods and constructs sound? [10] | Demands rigorous experimental designs with appropriate controls, validated feature sets, and representative data. |

| Intersubjective Testability | Can results be replicated and reproduced? [10] | Necessitates open scientific discourse, independent verification of findings, and transparent methodologies. |

| Individualization Framework | Can group data support individual conclusions? [10] | Requires a valid statistical framework (e.g., LRs) to bridge population-level research and case-specific inferences. |

These guidelines emphasize that scientific validation must address both group-level patterns and the more ambitious claim of individualization that is central to much forensic testimony [10]. The framework helps differentiate between scientifically grounded methods and those that rely primarily on untested expert assertion.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Contemporary forensic linguistics research requires specialized analytical tools and frameworks. The table below details key "research reagents" essential for conducting empirically valid forensic text comparison.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Forensic Text Comparison

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Role in Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Likelihood Ratio Framework | Quantifies the strength of textual evidence [12] | Provides a statistically sound framework for evaluating evidence, moving beyond categorical claims |

| Poisson Model | Feature-based statistical model for authorship attribution [12] | Offers theoretically appropriate method for handling count-based linguistic data |

| Cosine Distance | Score-based measure of textual similarity [12] | Provides baseline comparison for more advanced feature-based methods |

| Cllr (log-LR cost) | Performance metric for LR systems [12] | Validates the reliability and discriminative power of the forensic system |

| Machine Learning Algorithms | Identifies complex patterns in large text datasets [11] | Enables analysis of large datasets and subtle linguistic features beyond human capability |

| Feature Selection Algorithms | Identifies most discriminative linguistic features [12] | Improves model performance and helps establish plausible linguistic features |

| Annotated Text Corpora | Provides ground-truthed data for training and testing [12] | Enables empirical testing and validation of methods under controlled conditions |

| FSCPX | FSCPX | FSCPX is an irreversible A1 adenosine receptor antagonist for research. Recent studies indicate potential ectonucleotidase inhibition. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnosis or treatment. |

| FT011 | FT011, CAS:1001288-58-9, MF:C20H17NO5, MW:351.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The integration of machine learning, particularly deep learning and computational stylometry, has brought transformative potential to the field, enabling the processing of large datasets and identification of subtle linguistic patterns that elude manual analysis [11]. However, this technological advancement brings new validation challenges, including algorithmic bias, opaque decision-making, and legal admissibility concerns [11].

Visualization of Methodological Evolution and Validation Workflow

Diagram 1: Methodological Evolution in Forensic Linguistics

Diagram 1 illustrates the trajectory of forensic linguistics methodology from its origins in subjective manual analysis toward increasingly quantitative and computationally-driven approaches. This evolution represents a critical response to the historical validation gap, as each successive methodology has brought more testable, measurable, and empirically valid frameworks for analyzing linguistic evidence.

Diagram 2: Contemporary Validation Workflow for Forensic Text Comparison

Diagram 2 outlines the standardized experimental workflow for contemporary forensic text comparison research. This process emphasizes systematic data collection, transparent feature extraction, model development, and rigorous validation through the Likelihood Ratio framework and Cllr metric. The dashed line represents the application of the validation guidelines throughout this process, ensuring scientific rigor at each stage.

The historical lack of validation in forensic linguistics represents not merely an academic shortcoming but a fundamental challenge to the reliability of evidence presented in criminal justice systems. The field is currently undergoing a methodological transformation from its origins in subjective manual analysis toward computationally-driven, statistically-grounded approaches that prioritize empirical validation [11]. This transition is marked by the adoption of the Likelihood Ratio framework, the development of feature-based models like the Poisson model, and the implementation of rigorous validation metrics such as Cllr [12].

The future of empirically valid forensic linguistics likely lies in hybrid frameworks that merge the scalability and pattern-recognition capabilities of machine learning with human expertise in interpreting cultural and contextual nuances [11]. Addressing persistent challenges such as algorithmic bias, opaque decision-making, and the development of standardized validation protocols will be essential for achieving courtroom admissibility and scientific credibility [11]. As the field continues to develop, the guidelines approach to validation—emphasizing plausibility, research design validity, intersubjective testability, and a proper individualization framework—provides a critical roadmap for ensuring that forensic linguistics meets the demanding standards of both science and justice [10].

Forensic science is "science applied to matters of the law," an applied discipline where scientific principles are employed to obtain results that the courts can be shown to rely upon [13]. Within this framework, method validation—"the process of providing objective evidence that a method, process or device is fit for the specific purpose intended"—forms the cornerstone of reliable forensic practice [13] [14]. For forensic text comparison research, and indeed all forensic feature comparison methods, establishing foundational validity through empirical studies is not merely best practice but a fundamental expectation of the criminal justice system [15].

The central challenge in validation lies in demonstrating that a method works reliably under conditions that closely mirror real-world forensic casework. As noted in UK forensic guidance, "The extent and quality of the data on which the expert's opinion is based, and the validity of the methods by which they were obtained" are key factors courts consider when determining the reliability of expert evidence [13]. This article examines the core requirements for validating forensic text comparison methods, focusing specifically on the critical principles of replicating casework conditions and using relevant data, with comparative performance data from different methodological approaches.

Theoretical Framework: Validation Requirements for Forensic Methods

The Regulatory and Scientific Landscape

Recent decades have seen increased scrutiny of forensic methods through landmark reports from scientific bodies including the National Research Council (2009), the President's Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (2016), and the American Association for the Advancement of Science (2017) [15]. These reports consistently emphasize that empirical evidence is the essential foundation for establishing the scientific validity of forensic methods, particularly for those relying on subjective examiner judgments [15].

Judicial systems globally have incorporated these principles. The UK Forensic Science Regulator's Codes of Practice require that all methods routinely employed within the Criminal Justice System be validated prior to their use on live casework material [13]. Similarly, the U.S. Federal Rules of Evidence, particularly Rule 702, place emphasis on the validity of an expert's methods and the application of those methods to the facts of the case [15].

The Critical Role of Replicating Casework Conditions

A method considered reliable in one setting may not meet the more stringent requirements of a criminal trial. As observed in Lundy v The Queen: "It is important not to assume that well established techniques which are traditionally deployed for one purpose can be transported, without modification or further verification, to the forensic arena where the use is quite different" [13]. This underscores why replicating casework conditions during validation is indispensable.

Validation must demonstrate that a method is "fit for purpose," which requires that "data for all validation studies have to be representative of the real life use the method will be put to" [14]. If a method has not been tested previously, the validation must include "data challenges that can stress test the method" to evaluate its performance boundaries and failure modes [14].

Table 1: Key Elements for Replicating Casework Conditions in Validation Studies

| Element | Description | Validation Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Data Characteristics | Source, quality, and quantity of data | Must represent the range and types of evidence encountered in actual casework [14] |

| Contextual Pressures | Case context, time constraints, evidence volume | Testing should account for operational realities without introducing biasing information [15] |

| Tool Implementation | Specific software versions, hardware configurations | Method validation includes the interaction of the operator and may include multiple tools [14] |

| Administrative Controls | Documentation requirements, review processes | Quality assurance stages, checks, and reality checks by an expert should be included [14] |

Experimental Design: Implementing Validation Principles

Validation Workflow for Forensic Methods

The validation process follows a structured framework to ensure all critical aspects are addressed. The diagram below illustrates the key stages in developing and validating a forensic method, emphasizing the cyclical nature of refinement based on performance assessment.

This workflow demonstrates that validation is an iterative process. When acceptance criteria are not met, the method must be refined and re-tested, emphasizing that "the design of the validation study used to create the validation data must also be critically assessed" [14].

Experimental Protocol for Forensic Text Comparison

A recent empirical study compared likelihood ratio estimation methods for authorship text evidence, providing a exemplary model for validation study design [3]. The methodology included:

- Data Collection: Utilizing documents attributable to 2,157 authors to ensure statistical power and representativeness.

- Feature Selection: Employing a bag-of-words model with the 400 most frequently occurring words.

- Method Comparison: Comparing three feature-based methods (one-level Poisson model, one-level zero-inflated Poisson model, and two-level Poisson-gamma model) against a score-based method using cosine distance as a score-generating function.

- Performance Metrics: Evaluating via log-likelihood ratio cost (Cllr) and its components: discrimination (Cllrmin) and calibration (Cllrcal) cost.

This experimental design exemplifies proper validation through its use of forensically relevant data quantities, multiple methodological approaches, and comprehensive performance metrics that address both discrimination and calibration.

Comparative Performance Data

Method Performance in Text Comparison

The empirical comparison of score-based versus feature-based methods for forensic text evidence provides quantifiable performance data essential for validation assessment [3].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Text Comparison Methods

| Method Type | Specific Model | Cllr Value | Relative Performance | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Score-Based | Cosine distance | 0.14-0.2 higher | Baseline | Single similarity metric |

| Feature-Based | One-level Poisson | 0.14-0.2 lower | Superior | Models word count distributions |

| Feature-Based | Zero-inflated Poisson | 0.14-0.2 lower | Superior | Accounts for excess zeros in sparse data |

| Feature-Based | Poisson-gamma | 0.14-0.2 lower | Superior | Handles overdispersion in text data |

The results demonstrate that feature-based methods outperformed the score-based approach, with the Cllr values for feature-based methods being 0.14-0.2 lower than the score-based method in their best comparative results [3]. This performance gap underscores the importance of method selection in validation, particularly noting that "a feature selection procedure can further improve performance for the feature-based methods" [3].

Validation Metrics for Likelihood Ratio Methods

For likelihood ratio methods specifically, validation requires assessment across multiple performance characteristics, as illustrated in fingerprint evaluation research [16].

Table 3: Validation Matrix for Likelihood Ratio Methods

| Performance Characteristic | Performance Metrics | Graphical Representations | Validation Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Cllr | ECE Plot | According to definition and laboratory policy |

| Discriminating Power | EER, Cllrmin | ECEmin Plot, DET Plot | According to definition and laboratory policy |

| Calibration | Cllrcal | ECE Plot, Tippett Plot | According to definition and laboratory policy |

| Robustness | Cllr, EER | ECE Plot, DET Plot, Tippett Plot | According to definition and laboratory policy |

| Coherence | Cllr, EER | ECE Plot, DET Plot, Tippett Plot | According to definition and laboratory policy |

| Generalization | Cllr, EER | ECE Plot, DET Plot, Tippett Plot | According to definition and laboratory policy |

This comprehensive approach to validation ensures that methods are evaluated not just on a single metric but across the range of characteristics necessary for reliable forensic application. The specific "validation criteria" are often established by individual forensic laboratories and "should be transparent and not easily modified during the validation process" [16].

Implementing robust validation protocols requires specific tools and resources. The following table details key components necessary for conducting validation studies that replicate casework conditions and use relevant data.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Forensic Text Comparison Validation

| Tool Category | Specific Solution | Function in Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Data Resources | Authentic text corpora | Provides forensically relevant data representing real-world language use |

| Statistical Software | R, Python with specialized packages | Implements statistical models for likelihood ratio calculation |

| Validation Metrics | Cllr, EER, Cllrmin, Cllrcal | Quantifies method performance across multiple characteristics |

| Reference Methods | Baseline algorithms (e.g., cosine similarity) | Provides benchmark for comparative performance assessment |

| Visualization Tools | Tippett plots, DET plots, ECE plots | Enables visual assessment of method performance characteristics |

The validation of forensic text comparison methods demands rigorous adherence to the principles of replicating casework conditions and using relevant data. As the comparative data demonstrates, methodological choices significantly impact performance, with feature-based approaches showing measurable advantages over score-based methods in empirical testing [3]. The framework for validation—encompassing defined performance characteristics, appropriate metrics, and transparent criteria—provides the structure necessary to ensure forensic methods meet the exacting standards required for criminal justice applications [16].

Successful validation requires more than technical compliance; it demands a commitment to scientific rigor throughout the process, from initial requirement definition through final implementation. By embracing these principles, forensic researchers and practitioners can develop and implement text comparison methods that truly withstand judicial scrutiny and contribute to the fair administration of justice.

Forensic authorship attribution is a subfield of linguistics concerned with identifying the authors of disputed or anonymous documents that may serve as evidence in legal proceedings [17]. This discipline operates on the foundational theoretical principle that every native speaker possesses their own distinct and individual version of the language—their idiolect [18]. In modern contexts, where crimes increasingly occur online through digital communication, the linguistic clues left by perpetrators often constitute the primary evidence available to investigators [17]. The central challenge in this field lies in empirically validating methods that can reliably quantify individuality in language and distinguish it from variation introduced by situational factors, register, or deliberate disguise.

The growing volume of digital textual evidence from mobile communication devices and social networking services has intensified both the need for and complexity of forensic text comparison [19]. Among the various malicious methods employed, impersonation represents a particularly common technique that relies on manipulating linguistic identity [19]. Meanwhile, the rapid development of generative AI presents emerging challenges regarding the authentication of textual evidence and the potential for synthetic impersonation [19]. This article examines the current state of forensic text comparison methodologies within the broader thesis that the field requires more rigorous empirical validation protocols to establish scientific credibility and reliability in legal contexts.

Theoretical Foundations: The Idiolect Debate

The concept of idiolect—an individual's unique linguistic system—has long served as the theoretical cornerstone of forensic authorship analysis. The fundamental premise suggests that every native speaker exhibits distinctive patterns in their language use that function as identifying markers [18]. However, this theoretical construct faces significant challenges in empirical substantiation, with growing concern in the field that idiolect remains too abstract for practical application without operationalization through measurable units [18].

The theoretical underpinnings of idiolect face three primary challenges in forensic application:

- Abstract Nature: Idiolect exists as a theoretical construct that requires decomposition into analyzable components for forensic application

- Multidimensional Variation: An author's language varies register, genre, topic, and situational context, potentially obscuring identifying features

- Dynamic Evolution: Individual language patterns evolve, requiring temporal considerations in analysis

Despite these challenges, research has demonstrated that certain lexicogrammatical patterns exhibit sufficient individuality to serve as identifying markers [17]. The key theoretical advancement has been the conceptualization of idiolect not as a monolithic entity but as a constellation of linguistic habits, particularly evident in frequently used multi-word sequences that an author produces somewhat automatically [18].

Methodological Approaches: From Stylistics to Computational Linguistics

Traditional Stylistic Analysis

Traditional stylistic analysis in forensic linguistics involves the qualitative examination of authorial patterns, focusing on consistently used syntactic structures, lexical choices, and discourse features. Case study research using Enron email corpora has demonstrated that individual employees often exhibit habitual stylistic patterns, such as repeatedly producing politely encoded directives, which may characterize their professional communication [18]. This approach provides rich, contextual understanding of authorial style but faces challenges regarding subjectivity and limited scalability, particularly with large volumes of digital evidence.

Statistical and Computational Methods

Statistical approaches have emerged to address the limitations of purely qualitative analysis, with n-gram textbite analysis representing a particularly promising methodology. This approach identifies recurrent multi-word sequences (typically 2-6 words) that function as distinctive "textbites"—analogous to journalistic soundbites—that characterize an author's writing [18]. Experimental research using the Enron corpus of 63,000 emails (approximately 2.5 million words) from 176 authors has demonstrated remarkable success rates, with n-gram methods achieving up to 100% accuracy in assigning anonymized email samples to correct authors under controlled conditions [18].

Table 1: Success Rates of Authorship Attribution Methods

| Methodology | Data Volume | Success Rate | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| N-gram Textbite Analysis | 63,000 emails (2.5M words) | Up to 100% [18] | Identifies habitual multi-word patterns |

| Likelihood Ratio Framework | Variable casework | High discriminability [17] | Provides statistical probability statements |

| Sociolinguistic Profiling | Disputed statements | Investigative leads [17] | Estimates author demographics |

The likelihood ratio framework has emerged as a particularly robust methodological approach, providing a statistical measure of the strength of evidence rather than categorical authorship claims [17]. This framework evaluates the probability of the observed linguistic features under two competing hypotheses: that the questioned text was written by a specific suspect versus that it was written by someone else from a relevant population [17]. This approach aligns more closely with forensic science standards and has gained traction in both research and casework applications.

Experimental Protocols in Authorship Research

N-gram Textbite Methodology

The n-gram textbite approach follows a systematic protocol designed to identify and validate characteristic multi-word sequences:

- Corpus Compilation: Assemble a substantial collection of known-author texts (e.g., the Enron corpus containing 63,000 emails from 176 authors) [18]

- N-gram Extraction: Generate contiguous word sequences of specified lengths (typically 2-6 words) from the reference corpus

- Frequency Analysis: Identify n-grams that occur with significantly higher frequency in the target author's writing compared to a reference population

- Discriminative Power Assessment: Evaluate the candidate textbites' ability to distinguish the target author from others using statistical measures like Jaccard similarity

- Validation Testing: Apply the identified textbites to anonymized samples to measure attribution accuracy

This methodology effectively reduces a mass of textual data to key identifying segments that approximate the theoretical concept of idiolect in operationalizable terms [18].

Likelihood Ratio Framework Protocol

The likelihood ratio approach follows a distinct quantitative protocol:

- Feature Selection: Identify and quantify distinctive linguistic features in the questioned document

- Reference Population Definition: Establish appropriate comparison populations based on genre, register, and demographic factors

- Probability Calculation: Compute the probability of observing the linguistic features under both the prosecution and defense hypotheses

- Likelihood Ratio Computation: Calculate the ratio of these probabilities to quantify the strength of the evidence

- Validation: Test the method's discriminative power on known-author samples to establish error rates

This protocol emphasizes transparent statistical reasoning and acknowledges the probabilistic nature of authorship evidence [17].

Diagram 1: Likelihood Ratio Methodology Workflow

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Forensic Text Comparison

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Corpora | Provides baseline linguistic data for comparison | Essential for establishing population norms [18] |

| N-gram Extractors | Identifies recurrent multi-word sequences | Operationalizes idiolect through textbites [18] |

| Likelihood Ratio Software | Computes probability ratios for evidence | Implements statistical framework for authorship [17] |

| Stylometric Feature Sets | Quantifies stylistic patterns | Captures authorial fingerprints beyond content [17] |

| Validation Datasets | Tests method accuracy | Measures performance under controlled conditions [18] [17] |

The Enron email corpus represents a particularly valuable research reagent, comprising 63,000 emails and approximately 2.5 million words written by 176 employees of the former American energy corporation [18]. This dataset provides unprecedented scale and authenticity for developing and validating authorship attribution methods, as it represents genuine professional communication rather than artificially constructed texts. The availability of multiple messages per author enables within-author consistency analysis while the diversity of authors supports between-author discrimination testing.

Specialized software tools have been developed to implement these methodologies, including the Idiolect R package specifically designed for forensic authorship analysis [17]. These computational tools enable the processing of large text collections, extraction of linguistic features, statistical comparison, and validation of method performance—functions essential for empirical validation in forensic text comparison research.

Empirical Validation Requirements

The move toward empirically validated methods represents a paradigm shift in forensic linguistics. Traditional approaches often relied on expert qualitative judgment, but the field increasingly demands quantifiable error rates, validation studies, and clearly defined protocols that can withstand scientific and legal scrutiny [17]. This empirical validation requires:

- Standardized Testing Protocols: Methodologies must be tested on known-author datasets to establish baseline performance metrics [18]

- Error Rate Documentation: Techniques must provide transparent information about potential misattribution risks [17]

- Population-specific Validation: Methods should be validated against appropriate reference populations relevant to specific case contexts [17]

- Black-box Testing: Independent validation of methods without developer involvement to prevent confirmation bias

Research demonstrates that different methodological approaches yield varying success rates under different conditions. For instance, n-gram methods have shown remarkable effectiveness in email attribution but may require adjustment for other genres [18]. The likelihood ratio framework provides a mathematically robust approach but depends heavily on appropriate population modeling [17].

Diagram 2: Empirical Validation Cycle in Authorship Analysis

Emerging Challenges and Research Opportunities

The forensic analysis of linguistic evidence faces significant emerging challenges that create new research imperatives. The rapid development of generative AI coupled with growing internationalization and multilingualism in digital communications has profound implications for the field [19]. Specific challenges include:

- AI-generated Text Detection: Developing methods to distinguish between human-authored and synthetically generated text

- Multilingual Attribution: Adapting methodologies developed primarily for English to diverse linguistic contexts

- Cross-genre Reliability: Ensuring method performance generalizes across different communication genres

- Adversarial Countermeasures: Addressing deliberate attempts to disguise authorship or mimic others' styles

These challenges also present opportunities for methodological innovation. Research into detecting AI impersonation of individual language patterns represents an emerging frontier [17]. Additionally, the integration of sociolinguistic profiling with computational authorship methods offers promise for developing more robust author characterization frameworks [17].

Future research directions include developing more sophisticated population models, validating methods across diverse linguistic contexts, establishing standardized validation protocols, and creating adaptive frameworks that can address evolving communication technologies [19] [17]. The empirical validation framework provides the necessary foundation for addressing these emerging challenges while maintaining scientific rigor in forensic text comparison.

The complexity of textual evidence in authorship analysis requires sophisticated methodologies that can navigate the intricacies of idiolect, account for situational variables, and provide empirically validated results. The progression from theoretical constructs of idiolect to operationalized methodologies like n-gram textbite analysis and likelihood ratio frameworks represents significant advancement in the field's scientific maturity. However, continued empirical validation through standardized testing, error rate documentation, and independent verification remains essential for enhancing the reliability and legal admissibility of forensic text comparison evidence. As digital communication evolves and new challenges like generative AI emerge, the empirical validation framework provides the necessary foundation for maintaining scientific rigor while adapting to new forms of textual evidence.

Implementing the LR Framework: A Methodological Pipeline for FTC

Within forensic science, including the specific domain of Forensic Text Comparison (FTC), the Likelihood Ratio (LR) has been advocated as the logically correct framework for evaluating the strength of evidence [4]. An LR quantifies the support the evidence provides for one of two competing propositions: typically, the prosecution hypothesis ( Hp ) and the defense hypothesis ( Hd ) [4]. The two-stage process—an initial score calculation stage followed by a calibration stage—is critical for producing reliable and interpretable LRs. Empirical validation of this process is paramount, requiring that validation experiments replicate casework conditions and use relevant data [4]. Without proper calibration, the resulting LR values can be misleading, potentially overstating or understating the true strength of the evidence presented to the trier-of-fact [20].

This guide objectively compares the performance of different methodologies and calibration metrics used in this two-stage process, providing experimental data and protocols to inform researchers and forensic practitioners.

The Two-Stage Workflow: From Raw Evidence to Calibrated LR

The transformation of raw forensic data into a calibrated Likelihood Ratio follows a structured pipeline. The workflow diagram below illustrates the key stages and their relationships.

Stage 1: Score Calculation

The first stage involves reducing the complex, high-dimensional raw evidence into a single, informative score.

- Objective: To generate a scalar value that captures the degree of similarity between the trace (e.g., a questioned document) and a known source, and its typicality relative to a relevant population [4] [21].

- Process: Quantitative features are extracted from the evidence. For text, this might involve authorship attribution features (e.g., lexical, syntactic) or N-gram models (sequences of characters or words) [22]. For facial images, this is typically a similarity score from a deep learning model [23]. This feature vector is then processed by a statistical model (e.g., a Dirichlet-multinomial model for text) to produce a raw score [4] [22].

- Output: A raw, uncalibrated score that reflects the model's internal measure of match strength but is not yet a probabilistically interpretable LR.

Stage 2: Calibration

The second stage transforms the raw score into a valid Likelihood Ratio, ensuring its values are empirically trustworthy.

- Objective: To ensure that an LR of a given value (e.g., 100) genuinely corresponds to evidence that is 100 times more likely under Hp than under Hd [20]. A well-calibrated system satisfies the principle that "the LR of the LR is the LR" [20].

- Process: Calibration uses a separate training set of scores from known same-source (SS) and different-source (DS) comparisons to fit a model that maps raw scores to LRs [23] [21]. Common techniques include Platt Scaling (a logistic regression-based method) and Isotonic Regression (a non-parametric, monotonic method) [24].

- Output: A calibrated LR that can be meaningfully interpreted and used in Bayes' Theorem to update prior odds [4].

Experimental Comparison of System Performance

The performance of the two-stage LR process can be evaluated using various systems and calibration approaches. The following tables summarize quantitative results from published studies in forensic text and face comparison.

Table 1: Performance of Fused Forensic Text Comparison Systems (115 Authors) [22]

| Token Length | Model | Cllr | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 500 | MVKD (Authorship Features) | 0.29 | Good performance |

| Word N-gram | 0.54 | Moderate performance | |

| Character N-gram | 0.51 | Moderate performance | |

| Fused System | 0.21 | Best performance | |

| 1500 | MVKD (Authorship Features) | 0.19 | Very good performance |

| Word N-gram | 0.43 | Moderate performance | |

| Character N-gram | 0.41 | Moderate performance | |

| Fused System | 0.15 | Best performance | |

| 2500 | MVKD (Authorship Features) | 0.17 | Very good performance |

| Word N-gram | 0.38 | Moderate performance | |

| Character N-gram | 0.36 | Moderate performance | |

| Fused System | 0.13 | Best performance |

Table 2: Performance of Automated Facial Image Comparison Systems [23]

| System / Condition | Cllr | ECE (Expected Calibration Error) |

|---|---|---|

| Forensic Experts (ENFSI Test) | 0.21 | 0.04 |

| Open Software (Naive Calibration) | 0.55 | 0.12 |

| Open Software (Quality Score Calibration) | 0.45 | 0.09 |

| Open Software (Same-Features Calibration) | 0.38 | 0.07 |

| Commercial Software (FaceVACs) | 0.07 | 0.02 |

Table 3: Comparison of Calibration Metrics for LR Systems [20]

| Metric | Measures | Key Finding from Simulation Study |

|---|---|---|

| Cllr (Log-Likelihood-Ratio Cost) | Overall quality of LR values, combining discrimination and calibration. | A primary metric for overall system validity and reliability. |

| devPAV (Newly Proposed Metric) | Deviation from perfect calibration after PAV transformation. | Showed excellent differentiation between well- and ill-calibrated systems and high stability. |

| mislHp / mislHd | Proportion of misleading evidence (LR<1 when Hp true, or LR>1 when Hd true). | Effective at detecting datasets with a small number of highly misleading LRs. |

| ICI (Integrated Calibration Index) | Weighted average difference between observed and predicted probabilities. | Useful for quantifying calibration in logistic regression models [25]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols