Empirical Validation in Forensic Linguistics: Protocols, Challenges, and Future Directions

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of empirical validation protocols in forensic linguistics, a field at the critical intersection of language, law, and data science.

Empirical Validation in Forensic Linguistics: Protocols, Challenges, and Future Directions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of empirical validation protocols in forensic linguistics, a field at the critical intersection of language, law, and data science. It explores the foundational necessity of validation for scientific defensibility, detailing specific methodological frameworks like the Likelihood Ratio and computational approaches. The content addresses significant challenges such as topic mismatch and data relevance, while offering optimization strategies for robust practice. Through a comparative examination of validation standards, this resource equips researchers, legal professionals, and forensic scientists with the knowledge to assess, implement, and advance reliable linguistic analysis in high-stakes legal and investigative contexts.

The Imperative for Empirical Validation in Forensic Linguistics

Empirical validation is a cornerstone of scientific reliability, providing the essential evidence that a method, technique, or instrument performs as intended. In forensic science, this process moves beyond theoretical appeal to rigorously demonstrate via observable data that a procedure is fit for its intended purpose within the justice system. The 2009 National Research Council (NRC) report starkly highlighted the consequences of its absence, finding that with the exception of nuclear DNA analysis, no forensic method had been "rigorously shown to have the capacity to consistently, and with a high degree of certainty, demonstrate a connection between evidence and a specific individual or source" [1]. This revelation underscored that techniques admitted in courts for decades, including fingerprints, firearms analysis, and bitemarks, lacked the scientific foundation traditionally required of applied sciences.

The call for robust empirical validation has only intensified. The 2016 President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST) report reinforced these concerns, concluding that most forensic feature-comparison methods still lacked sufficient empirical evidence of validity and emphasizing that "well-designed empirical studies" are especially crucial for methods relying on subjective examiner judgments [2]. This article delineates the core principles of empirical validation as defined by leading scientific bodies, providing a framework for researchers and practitioners to evaluate and enhance the reliability of forensic methodologies.

Core Principles and Guidelines for Empirical Validation

Inspired by the influential "Bradford Hill Guidelines" for causal inference in epidemiology, leading scholars have proposed a parallel framework for evaluating forensic feature-comparison methods [1]. This guidelines approach offers a structured yet flexible means to assess the scientific validity of forensic techniques. The framework consists of four central pillars, which together provide a comprehensive foundation for establishing empirical validation.

Table 1: Core Guidelines for Evaluating Forensic Feature-Comparison Methods

| Guideline | Core Question | Key Components |

|---|---|---|

| Plausibility | Is the method based on a sound, scientifically reasonable theory? | Underlying principles must be scientifically credible and generate testable predictions. |

| Research Design & Methods | Was the validation study well-designed and properly executed? | Encompasses construct validity (does it measure what it claims?) and external validity (are results generalizable?). |

| Intersubjective Testability | Can the results be independently verified? | Requires that methods and findings be replicable and reproducible by different researchers. |

| Inference Methodology | Is there a valid way to reason from group data to individual cases? | Provides a logical, statistically sound framework for moving from population-level data to source-level conclusions. |

The Plausibility Principle

The first guideline, plausibility, demands that the fundamental theory underlying a forensic method must be scientifically sound and reasonable [1]. For instance, the theory that every individual possesses unique fingerprints—and that these unique features can be reliably transferred and captured at crime scenes—forms the plausible foundation for latent print analysis. Without such a plausible starting point, even extensive empirical testing may be built upon an unsound premise. This principle requires that the underlying principles generate testable predictions about what the evidence should show if the method is valid.

Research Design and Methodological Soundness

The second guideline addresses the soundness of research design and methods, encompassing both construct validity (does the test actually measure what it claims to measure?) and external validity (can the results be generalized to real-world conditions?) [1]. Well-designed empirical studies must replicate, as closely as possible, the conditions of actual casework, including the quality and nature of the evidence, to demonstrate foundational validity. The 2016 PCAST report specifically emphasized the importance of "well-designed" empirical studies, particularly for methods relying on human judgment, to establish both the validity of the underlying principles and the reliability of the method as applied in practice [2].

Intersubjective Testability and Replication

The principle of intersubjective testability requires that methods and findings be replicable and reproducible by different researchers in different laboratories [1]. This guards against findings that are merely artifacts of a specific laboratory setup, researcher bias, or chance. Replication is a cornerstone of the scientific method, and its absence in many forensic disciplines has been a significant criticism. For example, early claims of zero error rates in firearms identification [2] failed this fundamental test, as independent researchers could not replicate such perfection under controlled conditions.

From Group Data to Individual Cases

The final guideline requires a valid methodology to reason from group data to statements about individual cases [1]. This is particularly challenging in forensic science, where practitioners often need to move from population-level data (e.g., the general distinctiveness of fingerprints) to specific source attributions (e.g., this latent print originated from this particular person). The scientific framework for this inference is often probabilistic, with the Likelihood Ratio (LR) being widely endorsed as a logically and legally correct approach for evaluating forensic evidence [3]. The LR quantitatively expresses the strength of evidence by comparing the probability of the evidence under two competing hypotheses (typically the prosecution and defense hypotheses), providing a transparent and balanced assessment.

Empirical Validation in Practice: Forensic Linguistics Case Study

The field of forensic linguistics exemplifies both the challenges and progress in implementing rigorous empirical validation. This discipline has evolved from manual textual analysis to incorporate machine learning (ML)-driven methodologies, fundamentally transforming its role in criminal investigations [4].

Traditional vs. Modern Computational Approaches

Table 2: Comparison of Manual and Machine Learning Approaches in Forensic Linguistics

| Aspect | Traditional Manual Analysis | Machine Learning Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Strength | Interpreting cultural nuances and contextual subtleties [4]. | Processing large datasets rapidly and identifying subtle linguistic patterns [4]. |

| Accuracy | Variable, dependent on examiner expertise and experience. | Authorship attribution accuracy increased by 34% in ML models over manual methods [4]. |

| Efficiency | Time-consuming for large volumes of text. | High-speed analysis capable of processing massive datasets. |

| Reliability Concerns | Susceptible to contextual bias and subjective judgment. | Algorithmic bias from training data and opaque "black box" decision-making [4]. |

| Validation Status | Limited empirical validation historically [3]. | Growing but challenged by legal admissibility standards [4]. |

Implementing Validation Requirements in Forensic Text Comparison

For forensic text comparison (FTC), empirical validation must fulfill two critical requirements: (1) reflecting the conditions of the case under investigation, and (2) using data relevant to the case [3]. The complexity of textual evidence—influenced by authorship, social context, communicative situation, and topic—makes this particularly challenging. A key demonstration showed that validation experiments must account for mismatched topics between questioned and known documents, as this significantly impacts the reliability of authorship analyses [3].

The experimental protocol for proper validation in FTC involves:

- Defining Case Conditions: Identifying specific variables that may differ between documents (e.g., topic, genre, formality).

- Sourcing Relevant Data: Using textual databases that appropriately represent the linguistic variation under investigation.

- Statistical Modeling: Calculating Likelihood Ratios (LRs) using appropriate models (e.g., Dirichlet-multinomial model).

- Calibration and Assessment: Refining outputs via logistic-regression calibration and evaluating performance using metrics like log-likelihood-ratio cost and Tippett plots [3].

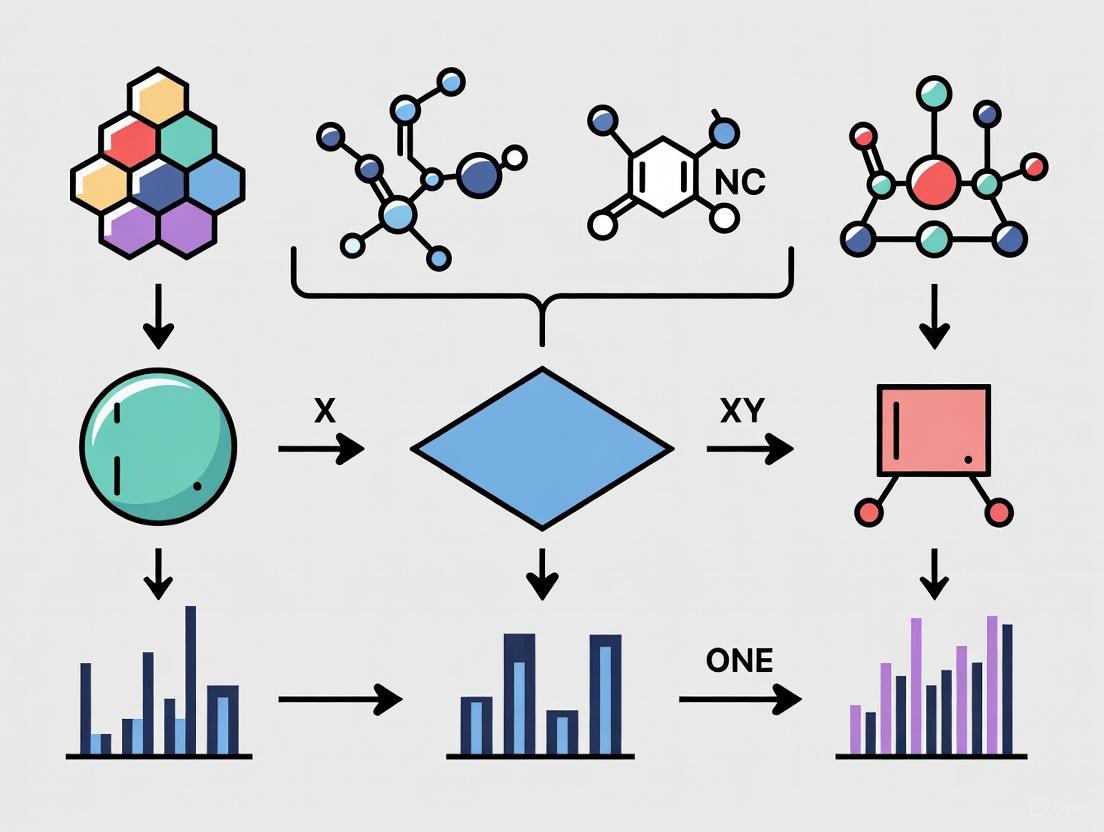

Diagram 1: Forensic Text Comparison Validation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents for Validation

Implementing robust empirical validation requires specific methodological tools and approaches. The following table details key "research reagents" - conceptual tools and frameworks - essential for conducting validation studies in forensic science.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Empirical Validation

| Research Reagent | Function in Validation | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Likelihood Ratio (LR) Framework | Quantitatively states the strength of evidence by comparing probability of evidence under competing hypotheses [3]. | Calculating whether writing style evidence is more likely under same-author or different-author hypotheses. |

| Blind Testing Procedures | Controls for contextual bias by preventing examiners from accessing extraneous case information [2]. | Submitting test samples to firearms examiners without revealing they are proficiency tests. |

| "Well-Designed" Empirical Studies | Establishes foundational validity under Rule 702(c) by testing methods under controlled conditions mirroring casework [2]. | Studies measuring accuracy of fingerprint examiners using realistic latent prints from crime scenes. |

| Error Rate Studies | Determines reliability of methods as applied in practice under Rule 702(d) by measuring how often methods produce incorrect results [2]. | Large-scale studies of forensic hair comparison revealing significant error rates. |

| Validation Databases | Provides relevant data that reflects the conditions of casework for testing method performance [3]. | Text corpora with matched topic variations for testing authorship attribution methods. |

Diagram 2: Likelihood Ratio Framework for Evidence Evaluation

Empirical validation remains the bedrock of scientific credibility in forensic science. The four guidelines—plausibility, sound research design, intersubjective testability, and valid inference from group to individual—provide a robust framework for evaluating forensic methodologies. As the field progresses, the tension between traditional practitioner experience and rigorous scientific standards continues to evolve, with courts increasingly demanding empirical foundations for expert testimony. For forensic linguistics specifically, the integration of computational methods with traditional analysis in hybrid frameworks offers promising pathways toward more validated, transparent, and reliable practice. Ultimately, the continued refinement and application of these core principles will determine whether forensic science fulfills its critical role as a scientifically grounded contributor to justice.

Forensic linguistics, the application of linguistic knowledge to legal and criminal matters, is undergoing a profound transformation driven by demands for greater scientific rigor and empirical validation [5] [6]. This field has evolved from relying primarily on expert opinion to increasingly adopting validated, quantitative methods supported by statistical frameworks [3] [7]. This shift mirrors developments in other forensic science disciplines where the traditional assumption of unique, identifiable patterns in evidence has been replaced by a probabilistic approach that requires empirical testing and validation [7]. The emergence of artificial intelligence (AI) and computational linguistics has further accelerated this transformation, enabling large-scale, nuanced analyses that extend beyond traditional applications like authorship attribution and deception detection [6].

This evolution addresses significant criticisms regarding the scientific foundation of forensic analyses. As noted in forensic science broadly, testimony about forensic comparisons has recently become controversial, with questions emerging about the scientific foundation of pattern-matching disciplines and the logic underlying forensic scientists' conclusions [7]. In response, forensic linguistics is increasingly embracing empirical validation protocols that require reflecting the conditions of the case under investigation and using data relevant to the case [3]. This article examines this methodological evolution through a comparative analysis of different approaches, their experimental validation, and their application in legal contexts.

Methodological Comparison: Three Paradigms in Forensic Linguistics

Table 1: Comparison of Forensic Linguistics Methodologies

| Methodological Approach | Validation Status | Quantitative Foundation | Key Strengths | Documented Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Expert Analysis | Limited validation; subjective assessment [3] | Qualitative | Holistic language assessment; contextual interpretation [5] | Susceptible to cognitive bias; lack of error rates [3] |

| Likelihood Ratio Framework | Empirically validated with relevant data [3] | Statistical probability | Transparent, reproducible, logically defensible [3] | Requires relevant population data; complex implementation [3] |

| Computational/AI-Driven Methods | Ongoing validation; performance metrics [6] [8] | Machine learning algorithms | Scalability; handles large data volumes; pattern detection [6] [8] | Algorithmic bias; "black box" problem; data requirements [6] [8] |

Experimental Protocols and Validation Standards

The Likelihood Ratio Framework for Authorship Analysis

The Likelihood-Ratio (LR) framework has emerged as a methodologically sound approach for evaluating forensic evidence, including textual evidence [3]. This framework provides a quantitative statement of the strength of evidence expressed as:

LR = p(E|Hp) / p(E|Hd)

Where p(E|Hp) represents the probability of the evidence assuming the prosecution hypothesis (typically that the suspect authored the questioned text) is true, and p(E|Hd) represents the probability of the evidence assuming the defense hypothesis (typically that someone else authored the text) is true [3].

Experimental Protocol: Validation of LR systems in forensic text comparison must fulfill two critical requirements: (1) reflecting the conditions of the case under investigation, and (2) using data relevant to the case [3]. For instance, when addressing topic mismatch between questioned and known documents, validation experiments should replicate this specific condition rather than using same-topic comparisons. The typical workflow involves:

- Feature Extraction: Measuring quantitative linguistic properties from source-questioned and source-known documents

- Statistical Modeling: Calculating likelihood ratios using appropriate models (e.g., Dirichlet-multinomial model)

- Calibration: Applying logistic-regression calibration to improve performance

- Validation Assessment: Evaluating derived LRs using the log-likelihood-ratio cost and visualizing with Tippett plots [3]

Diagram 1: LR Framework Validation Workflow

Computational Linguistics and AI-Driven Protocols

Computational approaches leverage natural language processing (NLP) and machine learning for forensic text analysis. The experimental protocol typically involves:

Data Collection and Preprocessing: Sourcing relevant textual data, which may include social media posts, formal documents, or malicious communications [8]. For malware analysis, this might involve execution reports from sandbox environments [9].

Model Selection and Training: Implementing appropriate algorithms based on the forensic task:

- BERT models for contextual understanding in cyberbullying and misinformation detection [8]

- Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) for image analysis and tamper detection in multimedia evidence [8]

- Transformer-based models for authorship attribution and stylistic analysis [6]

Validation Methodology: Employing a multi-layered validation framework that may include:

- Format validation and semantic deduplication

- Similarity filtering

- LLM-as-Judge evaluation for quality assessment [9]

- Performance metrics including accuracy, false positive rates, and fairness assessments

Diagram 2: Computational Forensic Analysis Process

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Forensic Linguistics Methodologies

| Methodology | Accuracy/Performance Data | Error Rates | Validation Scale | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Expert Analysis | Not empirically established [3] | Unknown error rates [3] [7] | Case studies and precedent | Subjective; vulnerable to contextual bias [3] |

| LR Framework | Log-likelihood-ratio cost assessment [3] | Quantifiable through Tippett plots [3] | Controlled experiments with relevant data [3] | Requires relevant population data; may not capture all linguistic features [3] |

| Computational Authorship | High accuracy in controlled conditions [6] | Varies by model and data quality [6] | Large-scale datasets (e.g., 5,000+ samples) [9] | Algorithmic bias; limited generalizability [6] [8] |

| Social Media Forensic Analysis | Effective in cyberbullying, fraud detection [8] | Impacted by data quality and platform changes [8] | Empirical studies with real-case validation [8] | Privacy constraints; API limitations [8] |

The performance data reveals significant differences in empirical validation across methodologies. For the LR framework, studies have demonstrated that proper validation requires replicating casework conditions, such as topic mismatch between compared documents [3]. Computational methods show promising results in specific applications: AI-driven social media analysis has proven effective for detecting cyberbullying, fraud, and misinformation campaigns, while NLP techniques enable analysis at unprecedented scales [8].

However, significant challenges remain across all approaches. Studies of fingerprint analysis (as a comparison point) have revealed false-positive rates that could be as high as 1 error in 18 cases based on certain studies, challenging claims of infallibility [7]. Similar empirical testing is needed across linguistic domains.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Forensic Linguistics

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| ForensicsData Dataset | Structured Question-Context-Answer resource for digital forensics [9] | Malware behavior analysis; training forensic analysis tools [9] |

| Dirichlet-Multinomial Model | Statistical model for calculating likelihood ratios [3] | Authorship attribution; forensic text comparison [3] |

| BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) | Contextual NLP for linguistic nuance detection [8] | Cyberbullying detection; misinformation analysis; semantic analysis [8] |

| Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) | Image analysis and pattern recognition [8] | Multimedia evidence verification; facial recognition; tamper detection [8] |

| Tippett Plots | Visualization method for assessing LR performance [3] | Validation of forensic inference systems; error rate representation [3] |

| Log-likelihood-ratio Cost (Cllr) | Performance metric for LR-based systems [3] | System validation and calibration assessment [3] |

Discussion: Implications for Research and Practice

The evolution of forensic linguistics from expert opinion to validated methods represents a significant advancement in the field's scientific rigor. The adoption of the Likelihood Ratio framework provides a logically defensible approach for evaluating evidence, while computational methods offer unprecedented scalability and analytical power [3] [6]. However, important challenges remain, including addressing algorithmic bias, ensuring linguistic inclusivity beyond high-resource languages, and developing robust validation protocols for diverse forensic contexts [6].

Future research should focus on expanding empirical validation across different linguistic features and casework conditions, developing standards for computational forensic tools, and addressing ethical implications of AI-driven analysis [3] [6]. As forensic linguistics continues to evolve, the integration of technological sophistication with methodological rigor will be essential for maintaining the field's scientific credibility and utility in legal proceedings.

Empirical validation is fundamental for establishing the scientific credibility of forensic linguistics methodologies, ensuring that analyses presented as evidence in legal proceedings are transparent, reproducible, and reliable. Within this framework, two requirements are paramount: the replication of case conditions and the use of relevant data [3]. These principles ensure that the validation of a method or system is performed under conditions that genuinely reflect the specific challenges of the case under investigation.

The analysis of textual evidence is complicated by the complex nature of language. A text encodes not just information about its author, but also about the author's social background and the specific communicative situation in which the text was produced, including factors like genre, topic, and formality [3]. Failure to account for these variables during validation, particularly by using non-relevant data, can lead to misleading results and potentially misinform the trier-of-fact [3]. This guide objectively compares the performance of different forensic linguistics approaches against these core validation requirements, providing researchers with the experimental data and protocols necessary for robust method evaluation.

Comparative Analysis of Methodological Approaches

The field of forensic linguistics has evolved from traditional manual analysis to computational and hybrid methods. The table below compares the key methodologies based on their adherence to empirical validation principles and their performance characteristics.

Table 1: Comparison of Forensic Linguistics Methodologies

| Methodology | Core Principle | Handling of Case Conditions | Data Relevance Requirements | Reported Performance/Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manual Linguistic Analysis [4] | Expert-based qualitative analysis of textual features. | Relies on expert to subjectively account for context. | High theoretical relevance, but dependent on expert's knowledge and available data. | Superior at interpreting cultural nuances and contextual subtleties [4]. | Lacks validation and quantitative rigor; susceptible to cognitive bias [3]. |

| Machine Learning (ML) & Deep Learning [4] | Automated identification of linguistic patterns from large datasets. | Must be explicitly designed into model training and testing protocols. | Critical; model performance can degrade significantly with irrelevant training data [3]. | Outperforms manual methods in processing speed and identifying subtle patterns (e.g., 34% increase in authorship attribution accuracy) [4]. | Opaque "black-box" decisions; can perpetuate algorithmic bias from poor training data; legal admissibility challenges [4] [3]. |

| Computational Stylometry (LambdaG) [10] | Models author's unique grammar ("idiolect") based on cognitive linguistics principles like entrenchment. | Grammar models are built from functional items, potentially making them more robust to topic changes. | Requires relevant population data to calculate typicality of an author's grammatical constructions [10]. | High verification accuracy; score is fully interpretable, allowing analysts to identify author-specific constructions [10]. | Relatively new method; requires further validation across diverse case types and populations. |

| Likelihood-Ratio (LR) Framework [3] | Quantifies evidence strength by comparing probability under competing hypotheses. | Validation must test the system under conditions that reflect the case (e.g., topic mismatch) [3]. | Data must be relevant to the hypotheses (e.g., correct population, topic, genre) to estimate reliable LRs [3]. | Provides a transparent, logically sound, and quantifiable measure of evidence strength for the court [3]. | Complex to implement; requires extensive, well-designed validation databases. |

Experimental Protocols for Empirical Validation

Adhering to standardized experimental protocols is essential for generating defensible validation data. The following section outlines a general workflow and specific methodologies for validating forensic text comparison systems.

General Workflow for Empirical Validation

The following diagram illustrates a high-level workflow for the empirical validation of a forensic linguistics method, incorporating the key requirements of replicating case conditions and using relevant data.

Detailed Methodological Protocols

1. Likelihood-Ratio (LR) with Dirichlet-Multinomial Model

- Objective: To empirically validate an authorship attribution method under specific case conditions like topic mismatch.

- Workflow:

- Case Condition Definition: Identify the specific condition to test (e.g., the known and questioned documents are on different topics) [3].

- Data Curation: Gather a validation corpus where document pairs are known to be from the same author or different authors, explicitly controlling for the defined condition (e.g., creating same-topic and cross-topic comparison sets) [3].

- Feature Extraction: Quantitatively measure linguistic features (e.g., character n-grams, function words) from the texts.

- LR Calculation: Compute Likelihood Ratios (LRs) using a statistical model, such as a Dirichlet-multinomial model, which handles count data well [3]. The LR is given by

LR = p(E|H_p) / p(E|H_d), whereEis the evidence,H_pis the prosecution hypothesis (same author), andH_dis the defense hypothesis (different authors) [3]. - Calibration & Evaluation: Apply logistic regression calibration to the output LRs. Assess performance using metrics like the log-likelihood-ratio cost (C_llr) and visualize results with Tippett plots [3].

2. LambdaG for Authorship Verification

- Objective: To verify whether a questioned text was written by a specific author by analyzing their idiolect, based on cognitive grammar.

- Workflow:

- Grammar Model Creation: For the suspected author, fit a grammar model (a type of language model) on a text representation containing only functional items (e.g., part-of-speech sequences like "NOUN VERB on the NOUN") from known writings [10].

- Population Model Creation: Create a similar grammar model from a relevant population of authors [10].

- Entrenchment Calculation: Process the questioned text to the same functional representation. Calculate the LambdaG score, which is the ratio of the probability assigned to the text by the author's model versus the population model. This ratio mathematically models the entrenchment of grammatical constructions for the author [10].

- Interpretation: A high LambdaG score supports the hypothesis that the author produced the text. The score is interpretable, allowing analysts to generate heatmaps to identify which specific constructions are most characteristic of the author [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

In forensic linguistics, "research reagents" refer to the core data, software, and analytical frameworks required to conduct empirical studies. The table below details key components for a research toolkit.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Forensic Linguistics Validation

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function in Validation | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relevant Text Corpora [3] | Data | Serves as the ground-truth dataset for testing method performance under specific case conditions. | Must be relevant to the case (author demographics, topic, genre, time period). Quality and quantity are critical. |

| Likelihood-Ratio (LR) Framework [3] | Analytical Framework | Provides the logical and mathematical structure for quantifying the strength of textual evidence. | Requires careful implementation and calibration. Output must be presented transparently. |

| Computational Stylometry Tool (e.g., LambdaG) [10] | Software/Method | Verifies authorship by modeling an author's unique grammar (idiolect) based on cognitive principles. | Offers interpretable results; requires fitting grammar models to relevant author and population data. |

| Machine Learning Libraries (e.g., for Deep Learning) [4] | Software/Method | Enables high-speed, automated analysis of large text datasets to identify subtle authorship patterns. | Risk of "black-box" decisions; requires vigilance for algorithmic bias; training data is critical. |

| Validation Metrics (C_llr, Tippett Plots) [3] | Analytical Tool | Measures the validity, reliability, and efficiency of a forensic inference system. | C_llr summarizes overall system performance. Tippett plots visually show the distribution of LRs for true and false hypotheses. |

| Functional Word Lists & Grammar Models [10] | Linguistic Resource | Provides the foundational features for stylistic analysis, crucial for methods like LambdaG. | Focus on high-frequency, context-independent items (e.g., function words, POS tags) can improve robustness. |

The rigorous empirical validation of forensic linguistics methodologies is non-negotiable for their acceptance as reliable scientific evidence in legal contexts. As the comparative data and protocols in this guide demonstrate, replicating case conditions and using relevant data are not merely best practices but foundational requirements that directly impact the accuracy and admissibility of an analysis.

While machine learning approaches offer unprecedented scalability and power, they introduce challenges related to interpretability and bias [4]. Conversely, novel methods like LambdaG show promise in bridging the gap between computational rigor and linguistic theory by providing interpretable results [10]. The prevailing evidence points to the superiority of hybrid frameworks that leverage the scalability of computational methods while retaining human expertise for contextual interpretation and oversight [4]. The future of defensible forensic linguistics research lies in the development and adherence to standardized validation protocols that are grounded in these core principles.

The evaluation of forensic evidence is undergoing a significant paradigm shift, moving from methods based on human perception and subjective judgment toward approaches grounded in relevant data, quantitative measurements, and statistical models [11]. This shift is particularly crucial in forensic linguistics, where the analysis of textual evidence can determine legal outcomes. Non-validated methods in forensic text comparison (FTC) pose substantial risks to the integrity of legal proceedings, as they lack transparency, reproducibility, and demonstrated reliability [3] [11]. The stakes are exceptionally high—unvalidated linguistic analysis can lead to wrongful convictions, the acquittal of the guilty, or the miscarriage of justice through the presentation of potentially misleading evidence to triers-of-fact.

Across most branches of forensic science, widespread practice has historically relied on analytical methods based on human perception and interpretive methods based on subjective judgement [11]. These approaches are inherently non-transparent, susceptible to cognitive bias, and often lack empirical validation of their reliability and error rates [11]. In forensic linguistics specifically, analyses based primarily on an expert linguist's opinion have been criticized for this lack of validation, even when the textual evidence is measured quantitatively and analyzed statistically [3]. This article examines the critical consequences of using non-validated methods in legal proceedings and compares the performance of traditional versus computationally-driven approaches through the lens of empirical validation protocols.

Performance Comparison: Validated vs. Non-Validated Methods

The table below summarizes key performance characteristics between traditional and modern computational approaches to forensic text comparison, highlighting the impact of empirical validation.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Forensic Text Comparison Methodologies

| Feature | Traditional Non-Validated Methods | Validated Computational Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Foundation | Subjective expert judgment based on linguistic features [12] | Quantitative measurements & statistical models (e.g., Likelihood Ratios) [3] [11] |

| Transparency & Reproducibility | Low; methods are often non-transparent and not reproducible [11] | High; methods, data, and software can be described in detail and shared [11] |

| Susceptibility to Cognitive Bias | High; susceptible to contextual bias and subjective interpretation [11] | Intrinsically resistant; automated evaluation processes minimize bias [11] |

| Empirical Validation & Error Rates | Often lacking or inadequate; difficulty establishing foundational validity [11] [12] | Measured accuracy and error rates established through controlled experiments [12] |

| Interpretative Framework | Logically flawed conclusions (e.g., categorical statements) [11] | Logically correct Likelihood-Ratio framework [3] [11] |

| Casework Application | Potentially misleading without known performance under case conditions [3] | Performance assessed under conditions reflecting casework realities [3] |

Experimental Evidence: Quantifying Method Performance

Controlled experiments provide crucial data on the actual performance of forensic text comparison methods. The table below summarizes findings from key validation studies that quantify accuracy under specific conditions.

Table 2: Experimental Validation Data from Forensic Text Comparison Studies

| Study Focus | Experimental Methodology | Key Performance Metrics | Implications for Legal Proceedings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Authorship Verification | Large-scale controlled experiments involving >32,000 English blog document pairs analyzed by a computational system [12] | 77% accuracy achieved across all document pairs [12] | Provides a measurable, transparent accuracy benchmark absent from non-validated methods |

| Machine Learning vs. Manual Analysis | Synthesis of 77 studies comparing manual and ML-driven forensic linguistics methods [4] | ML algorithms increased authorship attribution accuracy by 34% versus manual methods [4] | Highlights a significant performance gap favoring validated, computational approaches |

| Impact of Topic Mismatch | Simulated experiments using a Dirichlet-multinomial model and LR calibration, comparing matched and mismatched conditions [3] | Performance degradation when validation overlooks topical mismatch between compared documents [3] | Underscores that validation must replicate case-specific conditions (e.g., topic) to be meaningful |

Essential Protocols for Empirical Validation

Core Requirements for Validated Forensic Text Comparison

For a forensic evaluation system to be considered empirically validated, it must fulfill two primary requirements derived from broader forensic science principles [3]:

- Reflecting Case Conditions: The validation must replicate the conditions of the case under investigation. In textual evidence, this includes accounting for variables such as topic mismatch, genre, formality, and communication context that can influence writing style [3].

- Using Relevant Data: The data used for validation must be relevant to the specific case, representing the appropriate population and stylistic variations [3].

Failure to meet these requirements, such as by validating a method on topically similar texts when the case involves texts on different subjects, may provide misleading performance estimates and consequently mislead the trier-of-fact [3].

The Likelihood-Ratio Framework for Evidence Interpretation

The Likelihood-Ratio (LR) framework is widely advocated as the logically correct approach for evaluating forensic evidence, including textual evidence [3] [11]. The LR quantitatively expresses the strength of evidence by comparing two probabilities [3]:

Where:

Erepresents the observed evidence (e.g., the linguistic features in the questioned document)Hprepresents the prosecution hypothesis (e.g., the defendant wrote the questioned document)Hdrepresents the defense hypothesis (e.g., someone other than the defendant wrote the questioned document)

This framework forces transparent consideration of both the similarity between texts and their typicality within the relevant population, providing a more balanced and logical interpretation of evidence than categorical statements of identification [3] [11].

Diagram: The Likelihood Ratio Framework for evidence evaluation compares the probability of the evidence under two competing hypotheses.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents for Forensic Text Comparison

The experimental methodologies cited in performance comparisons rely on specific computational and statistical components. The table below details these essential "research reagents" and their functions in validated forensic text comparison.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Forensic Text Comparison

| Reagent Solution | Function in Experimental Protocol | Application in Forensic Linguistics |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Stylometry | Extracts and analyzes writing style patterns from digital texts [4] [12] | Identifies author-specific linguistic fingerprints for comparison |

| Machine Learning Algorithms (e.g., Deep Learning) | Classifies authorship based on learned patterns from training data [4] | Processes large datasets to identify subtle linguistic patterns beyond human perception |

| Likelihood-Ratio Statistical Models (e.g., Dirichlet-Multinomial) | Quantifies strength of evidence under competing hypotheses [3] | Provides logically correct framework for evaluating and presenting textual evidence |

| Validation Corpora (e.g., Blog Collections) | Provides ground-truthed data for controlled performance testing [12] | Enables empirical measurement of system accuracy and error rates |

| Feature Sets (e.g., Function Words, Character N-Grams) | Serves as measurable linguistic variables for analysis [12] | Provides quantitative measurements of writing style for statistical comparison |

| Calibration Techniques (e.g., Logistic Regression) | Adjusts raw model outputs to improve reliability [3] | Ensures Likelihood Ratio values accurately represent true strength of evidence |

Consequences of Non-Validated Methods in Legal Proceedings

Legal and Scientific Implications

The use of non-validated methods in legal proceedings carries significant consequences that undermine the pursuit of justice:

Questionable Foundational Validity: Without empirical evidence demonstrating accuracy and reliability, the scientific basis of the method remains unproven [11] [12]. As noted by the President's Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST), "neither experience, nor judgment, nor good professional practice … can substitute for actual evidence of foundational validity and reliability" [11].

Vulnerability to Cognitive Bias: Methods dependent on human perception and subjective judgment are intrinsically susceptible to cognitive bias, potentially influenced by task-irrelevant information [11]. This bias can affect both the analysis of evidence and its interpretation.

Inability to Meaningfully Assess Error Rates: Without controlled validation studies, there is no strong evidence suggesting any particular level of accuracy or reliability for human-based analysis [12]. This makes it difficult for legal decision-makers to assess the credibility of forensic evidence.

Logically Flawed Interpretation: Non-validated methods often employ logically flawed conclusions, such as categorical statements of identification ("this document was written by the suspect") based on the fallacious assumption of uniqueness [11].

Diagram: Non-validated methods in forensic linguistics introduce multiple concerns that can compromise legal decision-making.

The evolution of forensic linguistics from manual analysis to computationally-driven methodologies represents a critical advancement toward scientifically defensible evidence evaluation [4]. The experimental data clearly demonstrates that validated computational approaches provide measurable accuracy, transparency, and logical rigor absent from non-validated methods. The integration of machine learning with the Likelihood-Ratio framework offers a promising path forward, combining computational power with statistically sound evidence interpretation [3] [4].

For researchers and practitioners, this underscores the ethical and scientific imperative to demand empirical validation of any methodology presented in legal proceedings. Future work must focus on developing standardized validation protocols specific to textual evidence, addressing challenges such as cross-topic comparison, idiolect variation, and determining sufficient data quality and quantity for validation [3]. Only through such rigorous, empirically grounded approaches can forensic linguistics fulfill its potential as a reliable, transparent, and scientifically valid tool in the pursuit of justice.

The field of forensic linguistics is undergoing a profound transformation, shifting from traditional manual analysis to increasingly sophisticated digital and computational methodologies [4]. This evolution is fundamentally reshaping its role in criminal investigations and legal proceedings. The integration of machine learning (ML), particularly deep learning and computational stylometry, has enabled the processing of large datasets at unprecedented speeds and the identification of subtle linguistic patterns often imperceptible to human analysts [4]. This review objectively compares the performance of traditional manual techniques against emerging computational approaches, framing the analysis within the critical context of evaluating empirical validation protocols essential for the field's scientific rigor and legal admissibility.

Performance Comparison: Manual Analysis vs. Machine Learning

The quantitative comparison of manual and machine learning methods reveals distinct performance trade-offs. The table below summarizes key experimental data from synthesized studies [4] [13].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Manual and Machine Learning Approaches in Forensic Linguistics

| Performance Metric | Manual Analysis | Machine Learning Approaches | Key Supporting Experimental Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Authorship Attribution Accuracy | Baseline | Outperforms manual by ~34% [13] | ML algorithms, notably deep learning and computational stylometry, show a demonstrated 34% increase in authorship attribution accuracy compared to manual methods [4] [13]. |

| Data Processing Efficiency | Limited, labor-intensive for large datasets | High; rapid processing of massive datasets [4] | ML-driven Natural Language Processing (NLP) can process years' worth of communication data (emails, chats, logs) far more rapidly than manual review [14]. |

| Contextual & Nuanced Interpretation | Superior in interpreting cultural nuances and contextual subtleties [4] | Limited, depends on model training and design | Manual analysis retains superiority in areas requiring deep contextual understanding, such as interpreting cultural nuances and contextual subtleties that algorithms may miss [4]. |

| Bias and Interpretability | Subject to human analyst bias, but reasoning is transparent | Subject to algorithmic bias; decision-making can be opaque [4] | Key challenges include biased training data and opaque algorithmic decision-making ("black box" problem), which pose barriers to courtroom admissibility [4] [15]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Computational Authorship Attribution

Computational authorship attribution represents a significant area of performance improvement. The following protocol outlines a standard methodology for applying machine learning to this task, which has demonstrated a 34% increase in accuracy over manual methods in controlled studies [4] [13].

- Data Collection and Corpus Compilation: Researchers gather a closed set of text documents, including known documents from candidate authors and one or more documents of unknown authorship [10] [16]. This forms the experimental corpus, which may be drawn from publicly available repositories like the Threatening English Language (TEL) corpus or other forensic linguistic data collections [16].

- Feature Extraction: The text is converted into quantitative features for model consumption. Common features include:

- Stylometric Features: Frequency of function words (e.g., "the," "and," "of"), character n-grams, and syntactic patterns [10].

- Lexical Features: Vocabulary richness, word length distribution, and keyword usage.

- Syntax and Grammar Models: Modeling of grammatical constructions to represent an author's unique "entrenchment" of linguistic patterns, as seen in the LambdaG algorithm [10].

- Model Training and Validation: A machine learning model (e.g., a transformer-based deep learning model or a method like LambdaG) is trained on the feature sets extracted from the documents of known authorship. The model learns to distinguish between the stylistic fingerprints of the candidate authors. Performance is validated using techniques like k-fold cross-validation to ensure generalizability [4].

- Authorship Prediction and Analysis: The trained model analyzes the features of the unknown document(s) and computes a probability or likelihood score for each candidate author. In interpretable models like LambdaG, analysts can generate text heatmaps to identify which specific constructions were most influential in the attribution decision [10].

Protocol for Hybrid Analysis Framework

Given the complementary strengths of manual and computational approaches, a hybrid framework is often advocated for robust forensic analysis [4]. The workflow below integrates both methodologies.

Figure 1: Workflow of a hybrid forensic linguistics analysis framework integrating computational power with human expertise.

- Computational Triage and Pattern Identification: The process begins with digital text evidence being processed by ML algorithms (e.g., NLP for topic detection, sentiment analysis, or anomaly detection) [14]. This step rapidly identifies potential patterns of interest, such as specific keywords, stylistic consistencies, or deceptive cues, from large volumes of data.

- Human Expert Review and Interpretation: The outputs, anomalies, and patterns flagged by the computational tools are then reviewed by a human forensic linguist [4]. The expert applies qualitative analysis to interpret the results within their broader context, assessing cultural nuances, pragmatic implications, and the potential for algorithmic bias that the model may not account for [15].

- Synthesis and Reporting: The findings from both the computational and manual analyses are synthesized into a comprehensive report. This report should transparently detail the methodologies used, the role of automated tools, and the interpretive judgment of the human expert, which is crucial for the evidence's admissibility in legal proceedings [4] [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Forensic linguistics research relies on a suite of specialized data resources and computational tools. The table below details key "research reagents" essential for conducting empirical research in this field.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources in Computational Forensic Linguistics

| Research Reagent | Function and Application | Example Sources / Instances |

|---|---|---|

| Specialized Linguistic Corpora | Provides foundational data for quantitative analysis, model training, and validation. Essential for ensuring research reproducibility. | Threatening English Language (TEL) corpus; school shooter database; police transcript collections [16]. |

| Computational Algorithms & Models | Core engines for automated analysis; perform tasks like authorship attribution, deception detection, and topic modeling. | LambdaG (for authorship verification based on cognitive entrenchment); Transformer-based models (e.g., BERT) for deep learning analysis [4] [10]. |

| Natural Language Processing (NLP) Tools | Enable machines to parse, understand, and generate human language. Used to extract features like syntax, semantics, and sentiment from raw text. | BelkaGPT (offline AI assistant for analyzing texts in a secure forensic environment); Other NLP pipelines for processing emails, chats, and logs [14]. |

| Digital Forensics Software Platforms | Integrated environments that facilitate evidence acquisition, data carving, and the application of multiple analysis techniques (including AI) from diverse digital sources. | Belkasoft X (for acquisition from mobile devices, cloud, and computers); Platforms with automation for hash calculation and file carving [14]. |

| Statistical Analysis Software | Used to quantify linguistic features, test hypotheses, and validate the statistical significance of findings from both manual and computational analyses. | R programming language (e.g., via the "idiolect" package for implementing LambdaG); Python with scikit-learn for building ML models [10]. |

Implementing Robust Validation Frameworks and Methods

The Likelihood Ratio (LR) framework provides a logically sound and scientifically rigorous methodology for the evaluation of evidence across various forensic disciplines. This guide objectively compares the LR framework with alternative evidence evaluation methods, with a specific focus on its application and empirical validation within forensic linguistics research. By synthesizing current research on LR comprehension, methodological implementations, and validation protocols, this article provides researchers and practitioners with a critical analysis of the framework's performance metrics, strengths, and limitations. Supporting data are presented in structured tables, and key experimental workflows are visualized to enhance understanding of this quantitatively-driven approach to forensic evidence evaluation.

The Likelihood Ratio (LR) framework represents a fundamental shift from categorical to continuous evaluation of forensic evidence, rooted in Bayesian probability theory. The core logic of the LR quantifies the strength of evidence by comparing the probability of observing the evidence under two competing propositions: the prosecution's hypothesis (Hp) and the defense's hypothesis (Hd) [18]. This produces a ratio expressed as LR = P(E|Hp) / P(E|Hd), which theoretically provides a transparent and balanced measure of evidentiary strength without directly assigning prior probabilities, a task reserved for judicial decision-makers.

Forensic science communities, particularly in Europe, have increasingly advocated for the LR as the standard method for conveying evidential meaning, as it aligns with calls for more quantitative and transparent forensic practices [19] [18]. Proponents argue that the LR framework offers a logically coherent structure that forces explicit consideration of alternatives and mitigates against common reasoning fallacies. However, the implementation of this framework faces practical challenges, including questions about its understandability for legal decision-makers and the complexities of its empirical validation [20].

Within forensic linguistics specifically, the LR framework provides a structured approach for evaluating authorship, voice, or language analysis evidence. The framework's flexibility allows it to be adapted to various types of linguistic data while maintaining a consistent statistical foundation for expressing evidential strength.

Comparative Analysis of Evidence Evaluation Frameworks

Key Methodological Approaches

Forensic evidence evaluation employs several distinct methodological frameworks, each with characteristic approaches to interpreting and presenting evidentiary significance.

Likelihood Ratio Framework: The LR represents a Bayesian approach that quantifies evidence strength numerically or verbally. It requires experts to consider the probability of evidence under at least two competing propositions, promoting balanced evaluation. The framework explicitly acknowledges the role of prior probabilities while separating the expert's statistical assessment from the fact-finder's domain. Implementation requires appropriate data resources and statistical models, with complexity varying by discipline [21] [18].

Identity-by-Descent (IBD) Segment Analysis: Commonly used in forensic genetic genealogy, IBD methods identify shared chromosomal segments between individuals to infer familial relationships. This approach leverages dense single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) data and segment matching algorithms to establish kinship connections, often for investigative lead generation rather than formal statistical evidence presentation [21].

Identity-by-State (IBS) Methods: IBS approaches assess similarity based on matching alleles without distinguishing whether they were inherited from a common ancestor. While computationally simpler, IBS methods may be less powerful for distant relationship inference compared to IBD approaches, particularly in complex pedigree analyses [21].

Categorical Conclusion Frameworks: Traditional forensic reporting often uses categorical conclusions with fixed classifications. These methods provide seemingly definitive answers but may oversimplify complex evidence and obscure uncertainty, potentially leading to cognitive biases in interpretation.

Performance Metrics and Experimental Data

The following tables summarize quantitative performance data from empirical studies comparing different evidence evaluation approaches, with particular focus on kinship analysis and comprehension studies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Kinship Analysis Methods Using SNP Data

| Method | Relationship Types Tested | Accuracy | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LR-based (KinSNP-LR) | Up to second-degree relatives | 96.8% (126 SNPs, MAF >0.4) [21] | Provides statistical support aligned with traditional forensic standards; Dynamic SNP selection | Requires appropriate reference data; Computational complexity |

| IBD Segment Analysis | Near and distant kinship | High for close relatives [21] | Powerful for investigative lead generation; Comprehensive with WGS | Less formal statistical framework for evidence presentation |

| IBS Approaches | Primarily close relationships | Varies with marker informativeness [21] | Computational efficiency; No pedigree requirement | Less discrimination for distant relationships |

Table 2: Comprehension Studies of LR Presentation Formats

| Presentation Format | Sensitivity to LR Differences | Prosecutor's Fallacy Rate | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Numerical LR Values | Moderate to High [20] | Not significantly reduced with explanation [20] | Effective LRs were sensitive to relative differences in presented LRs |

| Verbal Equivalents | Not directly tested [19] | Not assessed | Conversion from numerical scales varies; Loses multiplicative property |

| With Explanation | Slight improvement [20] | No significant reduction [20] | Small increase in participants whose effective LR equaled presented LR |

Empirical validation of the LR framework in forensic genetics demonstrates its robust performance for relationship inference. In one implementation, a dynamically selected panel of 126 highly informative SNPs achieved 96.8% accuracy in distinguishing relationships up to the second degree across 2,244 tested pairs, with a weighted F1 score of 0.975 [21]. This highlights the potential for carefully calibrated LR approaches to deliver high discriminatory power even with modest marker sets when selected according to rigorous criteria.

Comprehension research presents a more nuanced picture. Studies evaluating lay understanding of LRs found that while participants' effective likelihood ratios (calculated from their posterior and prior odds) were generally sensitive to relative differences in presented LRs, providing explanations of LR meaning yielded only modest improvements in comprehension [20]. Notably, explanation of LRs did not significantly reduce occurrence of the prosecutor's fallacy, a fundamental reasoning error where the likelihood of evidence given guilt is misinterpreted as the likelihood of guilt given evidence [20].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Dynamic SNP Selection for Kinship Analysis

The KinSNP-LR methodology implements a sophisticated protocol for relationship inference that dynamically selects informative SNPs rather than relying on fixed panels [21]. This approach maximizes independence between markers and enhances discrimination power for specific case contexts.

The experimental workflow begins with a large, curated SNP panel from genomic databases such as gnomAD v4, which undergoes rigorous quality control and filtering for minor allele frequency (MAF > 0.4) and exclusion from difficult genomic regions [21]. The selection algorithm then traverses chromosomes, selecting the first SNP meeting MAF thresholds at chromosome ends, then subsequent SNPs at specified genetic distances (e.g., 30-50 centimorgans) that also satisfy MAF criteria. This ensures minimal linkage disequilibrium between selected markers.

LR calculations employ methods described in Thompson (1975), Ge et al. (2010), and Ge et al. (2011), computing the ratio of probabilities for the observed genotype data under alternative relationship hypotheses [21]. The cumulative LR is obtained by multiplying individual SNP LRs, assuming independence. Validation utilizes both simulated pedigrees (generated with tools like Ped-sim) and empirical data from sources such as the 1,000 Genomes Project, with performance assessed through accuracy metrics across known relationship categories.

LR Comprehension Experimental Design

Research on LR understanding employs carefully controlled experimental protocols to assess how different presentation formats and explanations influence lay comprehension. Typical studies present participants with realistic case scenarios through videoed expert testimony, systematically varying whether LRs are presented numerically, verbally, or with explanatory information [20].

The experimental protocol involves several key phases: first, participants provide their prior odds regarding case propositions before encountering the forensic evidence. They then view expert testimony presenting LR values, with experimental groups receiving different presentation formats or explanatory context. Finally, participants provide their posterior odds based on the evidence presented [20].

The critical dependent measure is the effective LR (ELR), calculated as the ratio of posterior odds to prior odds for each participant (ELR = Posterior Odds / Prior Odds) [20]. Researchers then compare ELRs to the presented LRs (PLRs) to assess comprehension accuracy. Additional analyses examine the prevalence of reasoning fallacies, particularly the prosecutor's fallacy, across experimental conditions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for LR Implementation

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| gnomAD v4 SNP Panel | Reference Data | Provides curated SNP frequencies across diverse populations [21] | Kinship analysis; Population genetics |

| 1,000 Genomes Project Data | Empirical Data | Offers whole genome sequences for method validation [21] | Relationship inference testing |

| Ped-sim | Simulation Software | Simulates pedigrees and phased genotypes with recombination [21] | Experimental design; Power analysis |

| KinSNP-LR | Analytical Algorithm | Dynamically selects SNPs and computes likelihood ratios [21] | Kinship analysis; Forensic genealogy |

| IBIS | Bioinformatics Tool | Identifies IBD segments and confirms unrelated individuals [21] | Quality control; Relationship screening |

| Color Contrast Analyzers | Accessibility Tools | Ensures visualizations meet WCAG contrast standards [22] [23] | Data visualization; Research dissemination |

The implementation of robust LR frameworks requires both specialized data resources and analytical tools. Curated SNP panels, such as the gnomAD v4 dataset of 222,366 SNPs, provide the allele frequency foundations necessary for calculating likelihoods across diverse populations [21]. Empirical data from projects like the 1,000 Genomes Project offer essential validation benchmarks with known relationship structures.

Computational tools including Ped-sim for pedigree simulation and KinSNP-LR for dynamic SNP selection and LR calculation enable the sophisticated analyses required for modern forensic genetics [21]. Additionally, accessibility tools such as color contrast analyzers ensure research visualizations comply with WCAG guidelines, with minimum contrast ratios of 4.5:1 for standard text and 7:1 for enhanced contrast requirements [22] [23].

Conceptual Foundations of the LR Framework

The theoretical underpinnings of the LR framework rest on Bayesian decision theory, which provides a normative approach for updating beliefs in the presence of uncertainty [18]. The fundamental Bayes' rule equation in odds form is: Posterior Odds = Prior Odds × Likelihood Ratio. This formulation cleanly separates the fact-finder's initial beliefs (prior odds) from the strength of the forensic evidence (LR).

A critical debate within the forensic science community concerns whether the LR value itself should be accompanied by uncertainty measures. Some proponents argue that the LR already incorporates all relevant uncertainties through its probability assessments, while others contend that additional uncertainty characterization is essential for assessing fitness for purpose [18]. This has led to proposals for frameworks such as the "lattice of assumptions" and "uncertainty pyramid" to systematically explore how LR values vary under different reasonable modeling choices [18].

The framework's theoretical soundness must also be evaluated against practical implementation challenges, particularly regarding its presentation to legal decision-makers. Research indicates that while the LR framework is mathematically rigorous, its effectiveness in legal contexts depends significantly on how it is communicated and understood by laypersons [19] [20].

The Likelihood Ratio framework represents a fundamentally sound approach to evidence evaluation that offers significant advantages in logical coherence and transparency over alternative methods. Empirical validation across forensic disciplines demonstrates its capacity for robust performance when implemented with appropriate methodological rigor, as evidenced by high accuracy rates in kinship analysis applications [21].

However, the framework's theoretical superiority does not automatically translate to practical effectiveness in legal contexts. Comprehension research indicates persistent challenges in communicating LR meaning to lay decision-makers, with limited improvement from explanatory interventions [20]. This suggests that optimal implementation requires attention not only to statistical rigor but also to presentation formats and contextual education.

For forensic linguistics research, the LR framework provides a structured pathway for empirical validation protocols, offering a consistent metric for evaluating methodological innovations across different linguistic domains. Future research directions should focus on developing discipline-specific LR models tailored to linguistic evidence, while simultaneously investigating more effective communication strategies for presenting statistical conclusions in legal settings.

Quantitative and Statistical Models for Forensic Text Comparison (FTC)

Forensic Text Comparison (FTC) has undergone a fundamental transformation, evolving from manual textual analysis to statistically driven methodologies. This shift is characterized by the adoption of quantitative measurements, statistical models, and the Likelihood Ratio (LR) framework, all underpinned by the critical requirement for empirical validation [3]. This evolution mirrors advancements in other forensic disciplines and aims to develop approaches that are transparent, reproducible, and resistant to cognitive bias [4] [3]. The core of this modern paradigm is the use of the Likelihood Ratio, which provides a logically and legally sound method for evaluating the strength of textual evidence. This guide objectively compares the performance of leading probabilistic genotyping software used in FTC, detailing their methodologies, experimental data, and the essential protocols for their validation.

Comparative Analysis of Forensic Genotyping Software

The analysis of complex forensic mixture samples, including those derived from text-based data, relies on specialized software. These tools are broadly categorized into qualitative and quantitative models. Qualitative software considers only the presence or absence of features (e.g., alleles in DNA or specific stylometric features in text), while quantitative software also incorporates the relative abundance or intensity of these features [24]. The following section provides a detailed comparison of three prominent tools.

LRmix Studio (v.2.1.3): A qualitative software that focuses on the discrete, qualitative information from forensic samples. It computes Likelihood Ratios based on the detected features (e.g., alleles) without utilizing quantitative data such as peak heights or feature intensities. Its model is inherently more conservative as it does not leverage the rich information provided by quantitative metrics [24].

STRmix (v.2.7): A quantitative software that employs a continuous model. It incorporates both the qualitative (what features are present) and quantitative (the intensity or weight of those features) information from the electropherogram or textual data output. This allows for a more nuanced and efficient interpretation of complex mixtures by modeling peak heights and other continuous metrics, generally leading to stronger support for the correct hypothesis when the model assumptions are met [24].

EuroForMix (v.3.4.0): An open-source quantitative software that, like STRmix, uses a continuous model to evaluate both qualitative and quantitative aspects of the data. It is based on a probabilistic framework that can handle complex mixture profiles. While its overall approach is similar to STRmix, differences in its underlying mathematical and statistical models can lead to variations in the computed LR values compared to other quantitative tools [24].

Performance Comparison Based on Experimental Data

A comprehensive study analyzed 156 pairs of anonymized real casework samples to compare the performance of these software tools. The sample pairs consisted of a mixture profile (with two or three contributors) and a single-source profile for comparison [24]. The table below summarizes the key quantitative findings.

Table 1: Software Performance on Real Casework Samples [24]

| Software | Model Type | Typical LR Trend (2 Contributors) | Typical LR Trend (3 Contributors) | Reported Discrepancies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LRmix Studio | Qualitative | Generally lower LRs | Generally lower LRs | Greater discrepancies observed vs. quantitative tools |

| STRmix | Quantitative | Generally higher LRs | Lower than 2-contributor LRs | LRs generally higher than EuroForMix |

| EuroForMix | Quantitative | Generally higher LRs | Lower than 2-contributor LRs | LRs generally lower than STRmix |

The experimental data revealed several key findings:

- Qualitative vs. Quantitative: The most significant differences were found between the qualitative tool (LRmix Studio) and the quantitative tools. Quantitative software consistently generated higher LR values, providing stronger support for the correct hypothesis in most cases [24].

- Quantitative vs. Quantitative: While the results from STRmix and EuroForMix were closer, observable differences still existed. The study found that STRmix generally produced higher LRs than EuroForMix, underscoring that different mathematical implementations within the quantitative paradigm can impact the final output [24].

- Effect of Complexity: As expected, mixtures with three estimated contributors resulted in lower LR values across all software platforms compared to two-contributor mixtures, reflecting the increased interpretive challenge [24].

Experimental Protocols for Empirical Validation

The empirical validation of any FTC system is paramount. Validation must be performed by replicating the conditions of the case under investigation and using data relevant to the case [3]. Overlooking this requirement can mislead the trier-of-fact. The following workflow and methodology detail a robust validation protocol.

Figure 1: Workflow for the empirical validation of an FTC methodology.

Detailed Validation Methodology

The methodology illustrated in Figure 1 can be broken down into the following steps, using the topic mismatch study as a specific case [3]:

Define Casework Conditions and Select Relevant Data: The first step is to identify the specific conditions of the case under investigation. In the referenced study, the condition was a mismatch in topics between the source-questioned and source-known documents. The experimental data must be selected to reflect this condition, ensuring it contains texts with known authorship but varying topics to simulate the real-world challenge [3].

Quantitative Measurement of Textual Features: The properties of the documents are measured quantitatively. This involves converting texts into numerical data. The specific features measured can vary but often include lexical, syntactic, or character-level features that are indicative of authorship style.

Likelihood Ratio Calculation via Statistical Model: The quantitatively measured features are analyzed using a statistical model to compute a Likelihood Ratio. The cited study employed a Dirichlet-multinomial model for this purpose [3]. The LR formula is: LR = p(E|Hp) / p(E|Hd) where:

- E represents the quantitative evidence from the texts.

- Hp is the prosecution hypothesis (the same author produced both documents).

- Hd is the defense hypothesis (different authors produced the documents) [3].

Logistic Regression Calibration: The raw LRs generated by the statistical model often undergo calibration to improve their reliability and interpretability. The study used logistic regression calibration to achieve this, ensuring that the LRs are well-calibrated and not misleadingly over- or under-confident [3].

Performance Evaluation: The calibrated LRs are rigorously assessed using objective metrics. The primary metric used in the study was the log-likelihood-ratio cost (Cllr). This metric evaluates the discriminative power and calibration of the LR system, with a lower Cllr indicating better performance [3]. Additionally, Tippett plots are used to visualize the distribution of LRs for both same-author and different-author comparisons, providing a clear graphical representation of the system's efficacy [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents for FTC

Successful implementation of quantitative FTC requires a suite of methodological "reagents." The following table details key components and their functions in a typical research or casework pipeline.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Forensic Text Comparison

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function & Purpose in FTC |

|---|---|

| Probabilistic Genotyping Software (e.g., STRmix, EuroForMix) | Interprets complex mixture data by computing a Likelihood Ratio (LR) using continuous probabilistic models that integrate both qualitative and quantitative information [24]. |

| Likelihood Ratio (LR) Framework | Provides the logical and legal structure for evaluating evidence, quantifying the strength of evidence for one hypothesis over another (e.g., same author vs. different author) [3]. |

| Validation Database with Relevant Data | A collection of textual data used for empirical validation; its relevance to casework conditions (e.g., topic, genre) is critical for demonstrating method reliability [3]. |

| Dirichlet-Multinomial Model | A specific statistical model used for calculating LRs from count-based textual data (e.g., word or character n-grams), modeling the variability in author style [3]. |

| Logistic Regression Calibration | A post-processing technique applied to raw LRs to improve their discriminative performance and ensure they are correctly scaled, enhancing reliability [3]. |

| Log-Likelihood-Ratio Cost (Cllr) | A primary metric for evaluating the performance of an LR-based system, measuring both its discrimination and calibration quality [3]. |

| Tippett Plots | A graphical tool for visualizing system performance, showing the cumulative proportion of LRs for both same-source and different-source conditions [3]. |

Forensic linguistics has undergone a profound transformation, evolving from traditional manual textual analysis to advanced machine learning (ML)-driven methodologies [4]. This paradigm shift is fundamentally reshaping the field's role in criminal investigations, offering unprecedented capabilities for processing large datasets and identifying subtle linguistic patterns. The integration of computational linguistics and artificial intelligence (AI) has enabled forensic researchers to move beyond qualitative assessment toward empirically validated, quantitative analysis of language evidence.

Within this context, the evaluation of empirical validation protocols becomes paramount. As computational approaches demonstrate remarkable capabilities—such as a documented 34% increase in authorship attribution accuracy with ML models compared to manual methods—the forensic linguistics community must establish rigorous validation frameworks to ensure these tools meet the exacting standards required for legal evidence [4]. This article examines the current state of NLP and machine learning applications in forensic linguistics, with particular emphasis on performance comparison, experimental methodologies, and the critical need for explainability in legally admissible analyses.

Performance Comparison: Computational vs Traditional Methods

The quantitative comparison between computational approaches and traditional manual analysis reveals distinct strengths and limitations for each methodology. The table below summarizes key performance metrics based on current research findings:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Manual vs. Computational Forensic Linguistics Methods

| Analysis Method | Authorship Attribution Accuracy | Processing Speed | Contextual Nuance Interpretation | Scalability to Large Datasets |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manual Analysis | Variable, dependent on expert skill | Slow, labor-intensive | Superior for cultural and contextual subtleties | Limited by human resources |

| Machine Learning Approaches | Up to 34% higher than manual methods [4] | Rapid, automated processing | Limited without specialized model architectures | Highly scalable with computational resources |

| Hybrid Frameworks | Combines strengths of both approaches | Moderate, with automated screening and manual verification | Excellent through human oversight of algorithmic output | Good, with computational pre-screening |

The data reveals that ML algorithms—particularly deep learning and computational stylometry—significantly outperform manual methods in processing velocity and identifying subtle linguistic patterns across large text corpora [4]. However, manual analysis retains distinct advantages in interpreting cultural nuances and contextual subtleties, underscoring the necessity for hybrid frameworks that merge human expertise with computational scalability.