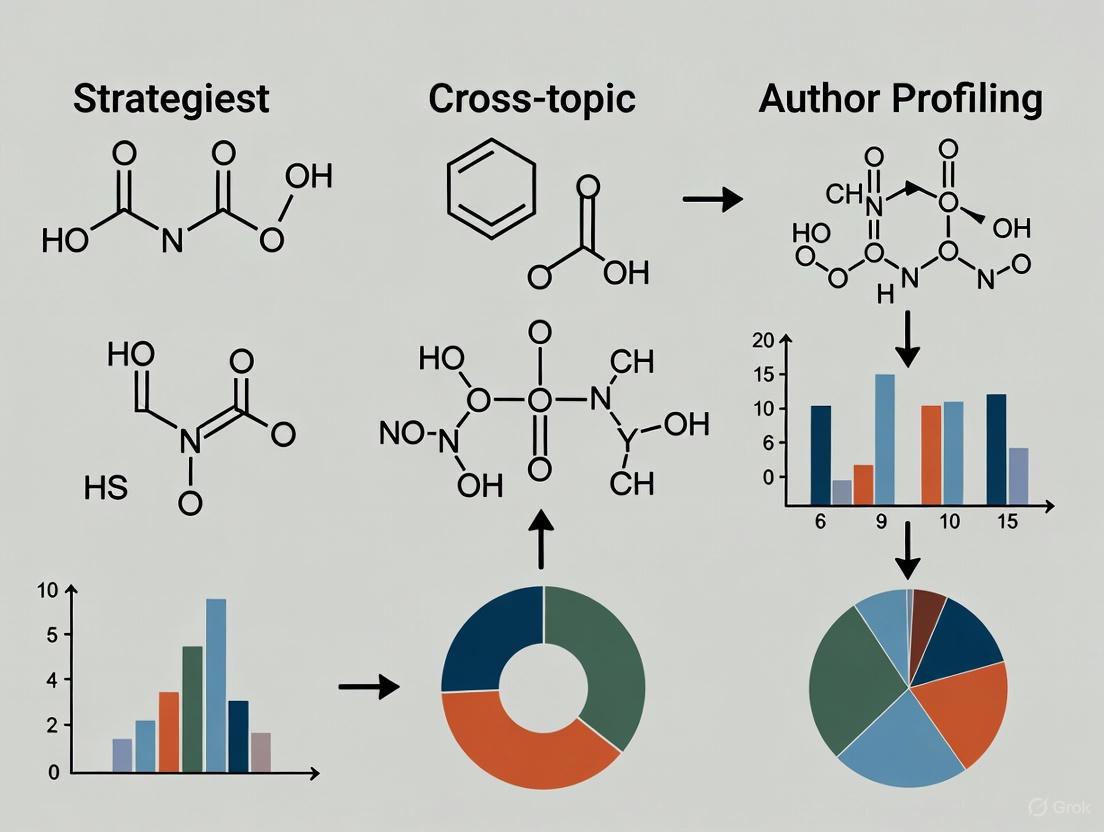

Cross-Topic Author Profiling: Advanced Strategies for Biomedical Research and Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive guide to cross-topic author profiling, a critical methodology for analyzing scientific text to infer researcher demographics and expertise without topical bias.

Cross-Topic Author Profiling: Advanced Strategies for Biomedical Research and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to cross-topic author profiling, a critical methodology for analyzing scientific text to infer researcher demographics and expertise without topical bias. Tailored for drug development professionals and computational biologists, we explore the foundational principles, from defining the task and its core challenges in biomedical contexts to advanced methodological approaches leveraging feature engineering and neural networks. The scope extends to troubleshooting common pitfalls like topic leakage and data bias, and concludes with robust validation frameworks and comparative analyses of modern techniques. This resource is designed to equip scientists with the strategies needed to build reliable, generalizable profiling models that can enhance literature-based discovery, collaboration mapping, and trend analysis in life sciences.

What is Cross-Topic Author Profiling? Core Concepts and Biomedical Relevance

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is author profiling, and why is it relevant to my research in scientific writing?

A: Author profiling is the computational analysis of textual data to uncover various characteristics of an author. In scientific contexts, this has two primary meanings:

- Computational Analysis: The analysis of writing style and content to predict author demographics like age, gender, or personality traits [1] [2]. This is crucial for applications in forensics, marketing, and security.

- Academic Identity: The process of establishing and maintaining a unique scholarly identity by linking your research outputs to your name [3] [4]. This ensures your work is properly attributed and discoverable, which is key for funding and collaboration.

For research on cross-topic author profiling, the focus is typically on the first definition, aiming to build models that can identify an author's traits regardless of the subject they are writing about [5].

Q2: What are the most critical linguistic features for profiling authors across different topics?

A: Effective cross-topic author profiling relies on stylistic features rather than content-specific words. This is because content words are topic-dependent, while stylistic features reflect the author's consistent writing habits. Key features include [1] [6] [2]:

- Stylistic Features: Character n-grams, function words, punctuation mark counts, average sentence length, and vocabulary richness.

- Syntactic Features: Part-of-Speech (POS) tags and their frequency.

- Structural Features: Discourse-based features and the overall structure of the text.

The table below summarizes feature types and their robustness for cross-topic analysis.

| Feature Category | Example Features | Usefulness in Cross-Topic Profiling |

|---|---|---|

| Stylistic & Syntactic | Function words, POS tags, punctuation, sentence length | High (Topic-invariant) |

| Content-Based | Topic-specific keywords, bag-of-words | Low (Topic-dependent) |

| Character-Based | Character n-grams, vowel/consonant ratios | High (Captures sub-word style) |

| Structural | Paragraph length, discourse markers | Moderate |

Q3: I'm working with code-switched text (like English-RomanUrdu). What specific challenges does this present?

A: Profiling authors of code-switched text presents unique challenges that require specialized approaches [5]:

- Lack of Standardization: No standardized spelling for transliterated words (e.g., RomanUrdu).

- Grammar Mixing: Interchangeable use of grammatical structures from different languages.

- Language Ambiguity: Words with identical spellings but different meanings across languages.

Recommended Solution: The Trans-Switch approach uses transfer learning. It involves:

- Splitting text into language-specific sentences (e.g., English vs. mixed).

- Applying specialized pre-trained language models to each sentence type.

- Fine-tuning models on unlabeled source text to improve language understanding.

- Aggregating sentence-level predictions for a final author profile [5].

Q4: What machine learning algorithms are most effective for author profiling tasks?

A: The field has evolved from traditional classifiers to deep learning and transfer learning models. The choice often depends on the data type and task.

| Algorithm Type | Example Algorithms | Common Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Traditional Machine Learning | Support Vector Machines (SVM), Naive Bayes, Logistic Regression [1] [2] | Smaller datasets, structured feature sets. |

| Deep Learning | Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN), Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN), Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) [1] [2] | Larger datasets, raw text input, capturing complex patterns. |

| Transfer Learning | BERT, XLMRoBERTa, ULMFiT [5] | State-of-the-art for many tasks, especially with limited labeled data or cross-genre/cross-lingual settings. |

Q5: How do I manage my academic author profile to ensure my expertise is correctly represented?

A: Proactively managing your academic profile is essential for career advancement. Key steps include [3] [4] [7]:

- Get an ORCID ID: Register for a free Open Researcher and Contributor ID. This is a persistent digital identifier that distinguishes you from other researchers and is a universal standard [4] [8].

- Claim Other Profiles: Regularly check and update your profile in key databases like Scopus Author Identifier and Web of Science ResearcherID (integrated with Publons) [4].

- Be Consistent: Use the same name version throughout your career to enhance discoverability. Consider using a full middle name or initial to distinguish yourself from researchers with similar names [4].

- Link and Sync: Link your ORCID iD with your other profiles (e.g., Scopus, ResearcherID) to automate updates and ensure consistency across platforms [4].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Standard Workflow for Author Profiling Experiments

The general process for building an author profiling system, as derived from research, involves several key stages [1] [2]. The following diagram illustrates this workflow.

Methodology for Cross-Genre Author Profiling

A primary challenge in real-world author profiling is the "cross-genre" problem, where a model trained on one type of text (e.g., tweets) must perform well on another (e.g., blog posts or reviews) [5]. The following workflow outlines a transfer learning approach designed to address this.

Detailed Protocol (Inspired by Trans-Switch [5]):

- Data Preparation: Secure datasets from at least two different genres (e.g., tweets and blog posts) where author demographics are known.

- Model Selection: Choose a pre-trained multilingual model like mBERT or XLM-RoBERTa, which are robust to informal and mixed-language text.

- Fine-Tuning: Fine-tune the selected model on the labeled source genre data (e.g., tweets). This teaches the model about author profiling for a specific genre.

- Language-Adaptive Retraining: To improve performance on the target genre, further retrain the model on the unlabeled text from the target genre (e.g., blogs). This step helps the model adapt to the new writing style and vocabulary without needing more labeled data.

- Evaluation: Finally, test the adapted model on the held-out, labeled portion of the target genre data to measure its cross-genre profiling accuracy.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

This table lists essential "research reagents"—datasets, tools, and resources—for conducting author profiling experiments.

| Tool/Resource Name | Type | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| PAN-CLEF Datasets [2] | Dataset | Standardized, multi-lingual benchmark datasets for author profiling and digital text forensics, used in international competitions. |

| Blog Authorship Corpus [2] | Dataset | A collection of blog posts with author demographics, commonly used for age and gender classification tasks. |

| BRNCI (British National Corpus) [2] | Dataset | A large and diverse corpus of modern English, containing both fiction and non-fiction texts for stylistic analysis. |

| mBERT (Multilingual BERT) [5] | Algorithm | A pre-trained transfer learning model designed to understand text in over 100 languages, ideal for cross-lingual or code-switched tasks. |

| XLM-RoBERTa [5] | Algorithm | A scaled-up, improved version of cross-lingual language models, offering high performance on a variety of NLP tasks across languages. |

| Support Vector Machines (SVM) [1] [2] | Algorithm | A classic, powerful classifier effective in high-dimensional spaces, often used with stylistic features in author profiling. |

| ORCID [3] [4] [7] | Profile System | A persistent digital identifier to ensure your scholarly work is correctly attributed and discoverable. |

| Scopus Author Identifier [4] | Profile System | Automatically groups an author's publications in the Scopus database, providing citation metrics and tracking output. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Cross-Topic Author Profiling

This guide addresses common issues researchers encounter when developing author profiling models that generalize across topics.

Q1: Why does my model's performance drop significantly when applied to a new topic domain?

A: This is a classic symptom of topic overfitting, where your model has learned topic-specific cues instead of genuine authorial style. To diagnose and address this:

- Diagnosis: Compare your model's in-topic and cross-topic performance metrics. A large performance gap indicates overfitting.

- Solution: Topic-Agnostic Feature Engineering. Prioritize features less dependent on topic semantics.

- Lexical: Use character n-grams, function word frequencies, and punctuation patterns [9].

- Syntactic: Focus on part-of-speech (POS) tag ratios, treebank structure, and sentence complexity scores.

- Structural: Analyze paragraph length, line breaks, and capitalisation consistency.

Q2: How can I create a training corpus that effectively reduces topic bias?

A: Curate your dataset with explicit control for topic distribution.

- Methodology: Implement a Multi-Topic, Multi-Author design. Ensure each author has written texts on multiple, distinct topics within your corpus. This forces the model to disentangle authorship from content.

- Data Collection Table: The following table summarizes the quantitative design for a robust corpus:

| Corpus Dimension | Target Minimum Quantity | Rationale for Generalizability |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Unique Authors | 500 | Provides sufficient stylistic diversity and reduces chance correlations. |

| Topics per Author | 3 | Compels the model to identify invariant features across an author's different works. |

| Documents per Author/Topic | 5 | Ensures enough data to model an author's style on a single topic. |

| Total Distinct Topics | 50 | Prevents the model from performing well by simply learning a limited set of topics. |

Q3: What validation strategy should I use to get a realistic estimate of cross-topic performance?

A: Standard train-test splits are insufficient. You must use a Topic-Holdout Validation strategy.*

- Protocol:

- Split by Topic: Partition all unique topics in your dataset into

kdistinct folds. - Iterate Training: For each iteration, train your model on data from

k-1topic folds. - Test on Unseen Topics: Evaluate the trained model on the one held-out topic fold, ensuring all authors and documents in the test set are from topics completely unseen during training.

- Aggregate Results: The final performance is the average across all

kfolds. This metric truly reflects cross-topic generalizability.

- Split by Topic: Partition all unique topics in your dataset into

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Essential computational materials and their functions for cross-topic author profiling experiments.

| Reagent / Solution | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Stylometric Feature Extractor | Software library (e.g., SciKit-learn) to generate topic-agnostic features like character n-grams and syntactic markers. |

| Pre-processed Multi-Topic Corpus | A foundational dataset adhering to the "Multi-Topic, Multi-Author" design, serving as the input substrate for all experiments. |

| Topic-Holdout Cross-Validation Script | A custom script that partitions data by topic folds to simulate real-world cross-topic application and evaluate model robustness. |

| Contrastive Loss Function | An advanced training objective that directly teaches the model to minimize intra-author variance while maximizing inter-author variance, regardless of topic. |

Experimental Protocol: Cross-Topic Generalizability Assessment

Objective: To quantitatively evaluate an author profiling model's ability to generalize to previously unseen topics.

Methodology:

- Dataset Preparation: Utilize a corpus structured as defined in the "Data Collection Table" above.

- Feature Extraction: For all documents, extract a feature vector comprising primarily topic-agnostic features (e.g., character 3-grams, POS tag trigrams, punctuation counts).

- Model Training & Validation:

- Implement the Topic-Holdout Validation protocol with

k=5folds. - For each fold, train a classification model (e.g., SVM, Random Forest) on the training topic folds.

- Apply the model to the held-out test topic fold.

- Implement the Topic-Holdout Validation protocol with

- Data Recording: For each fold, record standard performance metrics (Accuracy, F1-Macro) on the test set.

- Analysis: Calculate the mean and standard deviation of the performance metrics across all folds. This is the model's cross-topic performance. Compare it against a baseline in-topic performance (using standard random train-test splits) to quantify the performance drop.

Workflow Visualization: Cross-Topic Validation Logic

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow and iterative nature of the Topic-Holdout Validation protocol, which is critical for assessing model generalizability.

Troubleshooting Guide: AI-Powered Literature Mining

Problem: Overwhelming Volume and Complexity of Scientific Literature Researchers need to efficiently mine vast amounts of textual data from publications and patents to identify novel drug targets and understand disease mechanisms.

FAQ: How can AI language models accelerate drug target identification from literature?

Answer: AI large language models (LLMs) systematically analyze biomedical literature to uncover disease-associated biological pathways and potential therapeutic targets. These models overcome human reading limitations by processing millions of documents rapidly [10].

Experimental Protocol: Biomedical Relationship Extraction Using Domain-Specific LLMs

- Objective: Identify novel drug target-disease associations from biomedical literature.

- Materials:

- Hardware: Workstation with GPU (≥8GB VRAM)

- Software: Python 3.8+, Hugging Face Transformers library

- Models: BioBERT or PubMedBERT (pre-trained on PubMed/PMC)

- Data: PubMed/MEDLINE abstracts in XML or JSON format

- Methodology:

- Data Collection: Download relevant biomedical literature corpus using PubMed API or FTP.

- Pre-processing: Clean text, remove stop words, perform tokenization.

- Named Entity Recognition (NER): Use BioBERT to identify and extract biomedical entities (genes, proteins, diseases, compounds).

- Relationship Extraction: Apply relation classification models to establish "drug-target" or "target-disease" relationships.

- Knowledge Graph Construction: Integrate extracted entities and relationships into a structured knowledge graph for hypothesis generation.

- Troubleshooting Tips:

- For poor entity recognition, fine-tune BioBERT on domain-specific dictionaries.

- To reduce false-positive relationships, implement ensemble methods with multiple models.

- For handling contradictory findings, incorporate evidence-based scoring mechanisms.

AI-Powered Literature Mining Workflow for Target Identification

Research Reagent Solutions: Literature Mining

Table 1: Key AI Platforms and Tools for Drug Discovery Literature Mining

| Tool/Platform | Type | Primary Function | Application in Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| BioBERT [10] | Domain-specific LLM | Biomedical text mining | Named entity recognition, relation extraction from scientific literature |

| PubMedBERT [10] | Domain-specific LLM | Biomedical language understanding | Semantic analysis of PubMed content, concept normalization |

| BioGPT [10] | Generative LLM | Biomedical text generation | Literature-based hypothesis generation, summarizing research findings |

| ChatPandaGPT [10] | AI Assistant | Natural language queries | Target discovery through conversational interaction with PandaOmics platform |

| Galactica [10] | Specialized LLM | Scientific knowledge management | Extracting molecular interactions and pathway information from literature |

Troubleshooting Guide: Strategic Collaboration Finding

Problem: Identifying Optimal Partners for AI-Driven Drug Discovery Organizations struggle to identify complementary expertise and technologies in the rapidly evolving AI drug discovery landscape.

FAQ: What strategies effectively identify collaboration opportunities in AI drug discovery?

Answer: Successful collaborations combine complementary strengths—generative chemistry platforms with phenotypic screening capabilities, or AI design with experimental validation [11] [12]. The 2024-2025 period saw significant consolidation, such as Recursion's acquisition of Exscientia, creating integrated "AI drug discovery superpowers" [11].

Experimental Protocol: Systematic Partner Identification and Evaluation Framework

- Objective: Identify and evaluate potential collaborators with complementary AI drug discovery capabilities.

- Materials:

- Business intelligence tools (Crunchbase, LinkedIn)

- Scientific publication databases (PubMed, Google Scholar)

- Patent databases (USPTO, WIPO)

- Conference proceedings from major meetings (BIO, AACR)

- Methodology:

- Landscape Mapping: Identify companies, academic institutes, and platforms based on technological capabilities (e.g., generative chemistry, phenotypic screening, target discovery).

- Capability Assessment: Evaluate technological differentiators, clinical pipeline, platform validation, and data assets.

- Complementarity Analysis: Identify gaps in your platform that potential partners could fill.

- Success Probability Evaluation: Assess cultural alignment, IP positioning, and resource commitment.

- Partnership Structuring: Define collaboration models (licensing, co-development, equity investment).

- Troubleshooting Tips:

- For IP conflicts, establish clear ownership terms in initial agreements.

- To address data compatibility issues, implement standardized data formats early.

- For interdisciplinary communication barriers, create cross-functional teams with shared terminology.

Strategic Collaboration Identification Framework

Quantitative Analysis of AI Drug Discovery Landscape

Table 2: Leading AI-Driven Drug Discovery Companies and Their Clinical Stage Candidates (2025)

| Company | Core AI Technology | Key Clinical Candidates | Development Stage | Notable Achievements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exscientia [11] | Generative AI, Centaur Chemist | DSP-1181, EXS-21546, GTAEXS-617 | Phase I/II trials | First AI-designed drug (DSP-1181) to enter clinical trials (2020) |

| Insilico Medicine [11] [10] | Generative AI (PandaOmics, Chemistry42) | Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis drug, ISM042-2-048 | Phase II trials | Target to Phase I in 18 months for IPF; novel HCC target (CDK20) |

| Recursion [11] | Phenomics, ML | Multiple oncology programs | Phase I/II trials | Merger with Exscientia (2024) to create integrated platform |

| BenevolentAI [11] [13] | Knowledge Graphs, ML | Baricitinib (repurposed for COVID-19) | Approved (repurposed) | Identified baricitinib as COVID-19 treatment via AI knowledge mining |

| Schrödinger [11] | Physics-based Simulations, ML | Multiple small molecule programs | Preclinical/Phase I | Physics-based ML platform for molecular modeling |

Troubleshooting Guide: Drug Discovery Trend Analysis

Problem: Identifying Meaningful Trends Beyond Hype Researchers need to distinguish genuine technological breakthroughs from inflated claims in the rapidly evolving drug discovery field.

FAQ: What are the most significant validated trends in AI drug discovery for 2025?

Answer: The most significant trends include AI-platform maturation with clinical validation, integrated cross-disciplinary workflows, and the rise of specific modalities like targeted protein degradation and precision immunomodulation [11] [14] [15]. Success is now measured by concrete outputs: over 75 AI-derived molecules had reached clinical stages by end of 2024 [11].

Experimental Protocol: Systematic Trend Analysis and Validation Framework

- Objective: Identify, validate, and prioritize drug discovery trends for strategic planning.

- Materials:

- Bibliometric analysis tools (CiteSpace, VOSviewer)

- Clinical trial databases (ClinicalTrials.gov)

- Investment and partnership databases

- Scientific publication repositories

- Methodology:

- Data Collection: Aggregate data from publications, patents, clinical trials, and investments (2015-2025).

- Trend Identification: Use quantitative metrics (publication growth, clinical pipeline expansion, investment patterns).

- Validation Assessment: Evaluate clinical progress (candidates in Phase I, II, III), technological maturity, and industry adoption.

- Impact Projection: Analyze potential for paradigm shift versus incremental improvement.

- Strategic Prioritization: Rank trends based on organizational capabilities and strategic alignment.

- Troubleshooting Tips:

- To avoid hype, focus on clinical-stage validation rather than pre-clinical announcements.

- For data overload, implement AI-powered bibliometric analysis tools.

- To address confirmation bias, include contradictory evidence in analysis.

Systematic Trend Analysis and Validation Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions: Trend Validation

Table 3: Key Technological Enablers for 2025 Drug Discovery Trends

| Technology/Platform | Function | Trend Association | Validation Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| CETSA (Cellular Thermal Shift Assay) [15] | Target engagement validation in intact cells | Functional validation trend | Industry adoption for mechanistic confirmation |

| PandaOmics + Chemistry42 [10] | End-to-end AI target identification and compound design | AI-platform integration trend | Clinical validation (Phase II trials) |

| AlphaFold/ESMFold [10] [13] | Protein structure prediction | AI-driven structural biology trend | Widespread adoption, accuracy validated |

| PROTAC Technology [14] | Targeted protein degradation | Novel modality trend | >80 candidates in development |

| Digital Twin Platforms [14] | Virtual patient simulation for clinical trials | AI clinical trial optimization trend | Reduced placebo group sizes in Alzheimer's trials |

FAQ: How can researchers distinguish between AI hype and genuine capability in drug discovery?

Answer: Focus on platforms with clinical-stage validation, transparent performance metrics, and integrated wet-lab/dry-lab workflows. Genuine AI capabilities demonstrate measurable efficiency gains: Exscientia achieved clinical candidates with 70% faster design cycles and 10x fewer synthesized compounds [11]. Success requires interdisciplinary collaboration where "chemists, biologists, and data scientists work through early inefficiencies until they share a common technical language" [12].

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ 1: Topic Leakage in Cross-Topic Evaluation

Q: Our authorship verification models perform well in validation but fail on truly unseen topics. What is causing this, and how can we diagnose it?

A: This is a classic symptom of topic leakage, where models exploit topic-specific words and content features as a shortcut, rather than learning genuine stylistic patterns. This leads to misleading performance and unstable model rankings [16].

- Diagnosis: Implement the Topic Shortcut Test as part of your evaluation benchmark (e.g., the RAVEN benchmark) to explicitly quantify your model's reliance on topic-specific features [16].

- Solution: Utilize Heterogeneity-Informed Topic Sampling (HITS). This method constructs evaluation datasets with a controlled, heterogeneous distribution of topics, which reduces the impact of topic leakage and yields more stable and reliable model assessments [16].

Experimental Protocol: Implementing HITS for Robust Evaluation

- Topic Identification: Use an NLP taxonomy or topic modeling (e.g., LDA) to assign a topic label to each document in your corpus.

- Stratified Sampling: Instead of random sampling, strategically sample document pairs to ensure the test set contains a diverse and balanced mix of topics, minimizing the chance of any single topic dominating the signal.

- Cross-Topic Splitting: Guarantee that all documents in any training-validation-test split come from distinct, non-overlapping topics to simulate a true cross-topic scenario.

- Evaluation: Measure model performance on the HITS-sampled test set. A significant performance drop compared to a topic-biased set indicates previous topic leakage.

FAQ 2: Disentangling Stylistic and Content Features

Q: How can we ensure our model focuses on an author's unique writing style instead of being biased by the content of the document?

A: The core challenge is to isolate stylistic features (how something is written) from content features (what is written about). The solution involves careful feature engineering and model design [1].

- Diagnosis: Conduct an ablation study. Train and test your model using only content words (nouns, main verbs) versus only stylistic features (function words, syntax). A large performance drop with the latter suggests content bias.

- Solution: Prioritize style-markers that are largely independent of topic.

Quantitative Comparison of Feature Types

| Feature Category | Examples | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lexico-Syntactic (Style) | Function words (the, and, of), POS tag n-grams, sentence length [17] | Topic-agnostic, generalizable across genres [1] | Can be subtle and require large data to learn effectively [1] |

| Content-Based | Content words (nouns, specialized verbs), topic models, named entities [1] | Highly discriminative for within-topic tasks | Causes topic leakage, fails on cross-topic evaluation [16] |

| Structural | Paragraph length, punctuation usage, emoticons/kaomoji [1] | Easy to extract, robust across domains | Can be genre-specific (e.g., email vs. novel) |

Experimental Protocol: Feature Extraction for Stylistic Analysis

- Preprocessing: Tokenize text, remove stop words (with caution), and perform part-of-speech (POS) tagging.

- Feature Extraction:

- Function Words: Extract a predefined list of high-frequency function words (e.g., "the," "and," "of," "in").

- Character N-grams: Extract sequences of 'n' consecutive characters. This captures morphological patterns and spelling habits that are style-specific [17].

- Syntactic Features: Generate features from parse trees, such as production rule frequencies or dependency relations.

- Model Training: Use classifiers like Support Vector Machines (SVM) or Deep Averaging Networks (DAN) on the extracted stylistic features to build a topic-robust author profile [1].

FAQ 3: Mitigating Data Scarcity in Author Profiling

Q: For many authorship problems, we have very few texts per author. What strategies can we use to build reliable models with limited data?

A: Data scarcity is a fundamental challenge. The following strategies, adapted from low-data drug discovery, leverage transfer learning and data augmentation to overcome this [18].

- Diagnosis: Your model fails to converge or severely overfits, showing high performance on the training set but near-random accuracy on the test set.

- Solution: Implement a framework combining semi-supervised and multi-task learning.

Experimental Protocol: Semi-Supervised Multi-Task Training for Authorship

- Pre-training (Semi-Supervised): Take a large, unlabeled corpus (e.g., Wikipedia, news articles) and pre-train a transformer-based language model (e.g., BERT) using a Masked Language Modeling (MLM) objective. This teaches the model general language structure [19].

- Multi-Task Fine-Tuning:

- Primary Task: Authorship Verification. The model learns to predict if two texts are from the same author.

- Auxiliary Task: Continue using MLM on the (small) paired authorship dataset. This prevents catastrophic forgetting of linguistic knowledge and acts as a regularizer [19].

- Lightweight Interaction: Add a small cross-attention module on top of the base model to better fuse the representations of the two text pairs being compared for authorship [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Heterogeneity-Informed Topic Sampling (HITS) | An evaluation method that creates datasets with a heterogeneously distributed topic set to mitigate topic leakage and enable robust model ranking [16]. |

| Function Word Lexicon | A predefined list of words (e.g., "the," "and," "of") used as features to represent stylistic patterns that are largely independent of document topic [17]. |

| Character N-gram Extractor | A tool to generate sequences of 'n' characters from text, capturing sub-word stylistic markers like spelling, morphology, and idiomatic expressions [17]. |

| Pre-trained Language Model (e.g., BERT) | A model trained on a large, general corpus via self-supervision. It provides robust, contextualized word embeddings and can be fine-tuned for specific tasks with limited data [19] [18]. |

| Masked Language Modeling (MLM) Head | An auxiliary training task where the model learns to predict randomly masked words in a sentence. It is used during pre-training and multi-task fine-tuning to strengthen linguistic understanding [19]. |

| Cross-Attention Module | A lightweight neural network component that enables the model to focus on and interact with specific, relevant parts of two input texts, improving the comparison for verification [19]. |

| RAVEN Benchmark | The Robust Authorship Verification bENchmark, which includes a topic shortcut test specifically designed to uncover models' over-reliance on topic-specific features [16]. |

Building Robust Profiling Models: Techniques and Workflows for Scientific Text

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is Personal Expression Intensity (PEI), and why is it crucial for cross-topic author profiling?

Personal Expression Intensity (PEI) is a quantitative measure that scores the amount of personal information a term reveals based on its co-occurrence with first-person pronouns (e.g., "I", "me", "mine") [20]. It is calculated from two underlying metrics: personal precision (ρ) and personal coverage (τ) [20].

In cross-topic author profiling, where a model trained on one text genre (e.g., tweets) must perform on another (e.g., blogs or reviews), generalizable features are essential. PEI helps by emphasizing terms that reflect an author's consistent stylistic and thematic preferences—such as interests, opinions, and habits—which are more likely to remain stable across different topics or genres than content-specific words. This leads to more robust and transferable author profiles [20] [5].

FAQ 2: My model performs well on the training genre but fails on a new, unseen genre. What feature engineering strategies can improve cross-genre robustness?

This is a classic challenge in cross-genre author profiling, often caused by models overfitting to the specific vocabulary of the training genre. The following strategies can enhance generalization:

- Emphasize Personal Phrases: Use the PEI measure to create feature selection and weighting schemes that boost terms frequently used in personal contexts. This leverages psychologically stable writing patterns [20].

- Leverage Semantic Bigrams: Instead of relying solely on single words (unigrams), use bigram semantic distance. This measures the conceptual cohesion or "jump" between consecutive words, capturing stylistic flow that is less dependent on topic-specific vocabulary [21].

- Employ Transfer Learning: Utilize pre-trained language models (like BERT or ULMFiT) and fine-tune them on your source genre. For code-switched text (e.g., English mixed with another language), specialized approaches like the Tran-Switch model, which processes language segments separately, can be highly effective [5].

FAQ 3: How do I handle code-switched text (like English-RomanUrdu) in author profiling experiments?

Code-switched text presents challenges like non-standard spelling and mixed grammar. A proven methodology is the Tran-Switch approach [5]:

- Sentence Splitting by Language: Use a word-level language detection algorithm to split a writer's sample into monolingual (e.g., English) and mixed-language sentences.

- Specialized Model Application: Feed the monolingual sentences to a pre-trained model for that language (e.g., an English BERT). For mixed-language sentences, first "induce language-adaptiveness" by further pre-training the model on unlabeled source text, then use this adapted model for training.

- Aggregate Predictions: Make sentence-level predictions and use a consensus mechanism (e.g., the most prevalent class) to determine the final author attribute.

FAQ 4: What are the most common pitfalls when implementing a bigram-based semantic distance model?

- Incorrect Semantic Space: The choice of semantic space (e.g., GloVe, BERT, experiential models) fundamentally changes the distance meaning. Ensure the space is psychologically plausible for your task [21].

- Ignoring Sentence Boundaries: Semantic distance often spikes at sentence boundaries. Failing to account for this can confound measurements of conceptual flow within a narrative [21].

- Data Sparsity with Rare Bigrams: In smaller datasets, many possible word pairs may not appear, making frequency-based estimates unreliable. Smoothing techniques or the use of pre-trained word embeddings can mitigate this.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low PEI scores for all terms in a corpus, providing no discriminative power.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Genre lacks personal expression. | Calculate the frequency of first-person pronouns in the corpus. If it is very low, the genre (e.g., formal reports) may be inherently impersonal. | Consider a different profiling strategy that relies on syntactic features or topic models instead of personal expression [20]. |

| Incorrect pronoun list. | Verify the list of first-person pronouns used to define "personal phrases." Ensure it is comprehensive for the language (e.g., includes "I", "my", "mine", "me") [20]. | Expand the list of pronouns used to identify personal phrases. |

| Data preprocessing errors. | Check for tokenization errors. For example, if periods are not properly split, "I." might not be recognized as a pronoun. | Review and correct the text preprocessing pipeline, including sentence segmentation and tokenization. |

Problem: Model leveraging semantic bigrams shows poor cross-topic performance.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Semantic space mismatch. | Check if the word embedding model was trained on a corpus dissimilar to your text (e.g., using formal news articles to model social media). | Use a semantic space trained on a corpus that is domain- or genre-appropriate for your data [21]. |

| Feature explosion / high dimensionality. | Examine the number of bigram features. If it is very large relative to your sample size, overfitting is likely. | Apply dimensionality reduction (e.g., PCA) or feature selection (e.g., based on mutual information) to the bigram features [22] [23]. |

| Insufficient data for reliable distance calculation. | Calculate the frequency of your top bigrams. If most are rare, the distance measures will be noisy. | Increase training data volume or use a pre-trained model to get the initial vector representations, avoiding training from scratch [24]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Calculating Personal Expression Intensity (PEI)

This protocol outlines the steps to compute the PEI score for terms in a corpus, enabling the identification of words that carry significant personal information [20].

- Identify Personal Phrases: Scan the corpus to identify all sentences that contain at least one first-person singular pronoun (e.g., I, me, my, mine).

- Term Co-occurrence Counting:

- Let ( f{t}^{p} ) be the frequency of term ( t ) within all personal phrases.

- Let ( f{t}^{np} ) be the frequency of term ( t ) within all non-personal phrases.

- Let ( f_{t} ) be the total frequency of term ( t ) in the entire corpus.

- Calculate Core Metrics:

- Personal Precision (ρ): The proportion of a term's appearances that occur in a personal context. ( ρt = \frac{f{t}^{p}}{ f_{t} } )

- Personal Coverage (τ): The proportion of a term's appearances in personal phrases relative to all term appearances in personal phrases. This measures the term's prevalence in the personal landscape. ( τt = \frac{f{t}^{p}}{ \sum{t'} f{t'}^{p} } )

- Compute PEI Score: The Personal Expression Intensity is the product of personal precision and the logarithm of personal coverage. The log is used to smooth the impact of very high-coverage terms. ( PEIt = ρt \cdot \log(τ_t) )

Summary of Quantitative Data (Hypothetical Example):

The following table illustrates PEI calculation for sample terms, demonstrating how it prioritizes frequent, personally expressive words.

| Term (t) | Total Freq (f_t) | Freq in Personal Phrases (f_t^p) | Personal Precision (ρ_t) | Personal Coverage (τ_t) | PEI_t |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| think | 150 | 120 | 0.80 | 0.05 | -0.24 |

| data | 300 | 60 | 0.20 | 0.025 | -0.08 |

| python | 200 | 10 | 0.05 | 0.004 | -0.02 |

Protocol 2: Implementing a Bigram Semantic Distance Analysis

This protocol describes how to compute semantic distance between consecutive words (bigrams) to analyze conceptual flow in text, a useful feature for capturing writing style [21].

- Text Preprocessing: Tokenize the text into words. Apply cleaning steps like lowercasing and removal of punctuation. Optionally, add sentence boundary tokens (e.g.,

<S>and</S>). - Bigram Extraction: Create an ordered list of all consecutive word pairs (bigrams) from the processed text. For example, from "Cats drink milk," you get:

(Cats, drink),(drink, milk). - Vector Representation: For each word in a bigram, obtain its vector representation from a pre-trained word embedding model (e.g., Word2Vec, GloVe, BERT).

- Distance Calculation: For each bigram ( (wi, wj) ), calculate the semantic distance between the two word vectors. A common metric is cosine distance: ( \text{Distance} = 1 - \cos(\theta) = 1 - \frac{\vec{wi} \cdot \vec{wj}}{ \|\vec{wi}\| \|\vec{wj}\| } ), where ( \cos(\theta) ) is the cosine similarity.

- Analysis: Analyze the resulting vector of distances. For instance, average distance can measure overall conceptual cohesion, and distance peaks can indicate topic shifts or the end of sentences [21].

Bigram Semantic Distance Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| First-Person Pronoun Lexicon | A comprehensive, language-specific list of words (I, me, my, mine) used to identify "personal phrases" in the text corpus [20]. |

| Pre-trained Word Embeddings | A model (e.g., Word2Vec, GloVe) that provides the vector representations of words necessary for calculating semantic distance between bigram components [21]. |

| Pre-trained Language Model (PLM) | A base model (e.g., mBERT, XLNet) that can be fine-tuned for specific author profiling tasks, crucial for transfer learning in cross-genre or code-switching scenarios [5]. |

| Language Detection Tool | An algorithm for identifying the language of words or sentences, which is a critical first step for processing code-switched text in approaches like Tran-Switch [5]. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My model performs well on texts from one topic but fails on others. How can I improve cross-topic generalization?

A: This is a classic case of topic bias, where your model is learning topic-specific words instead of genuine stylistic patterns. The solution is to implement topic-debiasing. The TDRLM model addresses this by using a topic score dictionary and a multi-head attention mechanism to remove topical bias from stylometric representations. This allows the model to focus on topic-agnostic features like function words and personal stylistic markers [25].

Q2: What is the optimal text chunk size for intrinsic analysis when the authors are unknown?

A: Chunk size is a critical parameter. If it's too large, you may miss fine-grained style variations; if too small, the feature extraction may be unreliable. A common starting point is 10 sentences per chunk [26]. However, you should validate this for your specific corpus. Use the Elbow Method with K-Means to test different chunk sizes and observe which produces the most stable and interpretable clusters [26].

Q3: Which features are most important for distinguishing AI-generated text from human-authored content?

A: Based on the StyloAI model, key discriminative features include [27]:

- Lexical Diversity: Type-Token Ratio (TTR) and Hapax Legomenon Rate.

- Syntactic Complexity: Counts of complex verbs, contractions, and sophisticated adjectives.

- Emotional Depth: Emotion Word Count and sentiment polarity scores. AI-generated texts often show less lexical variety, simpler syntactic structures, and different emotional word usage patterns compared to human writers [27].

Q4: How can I determine the number of different writing styles or authors in a document without prior knowledge?

A: This is an unsupervised learning problem. The standard approach is [26]:

- Extract stylometric feature vectors from text chunks.

- Apply K-Means clustering.

- Use the Elbow Method to find the optimal number of clusters (K) by plotting the Sum of Squared Errors (SSE) against different K values. The "elbow" point—where the rate of SSE decrease sharply slows—indicates the most suitable number of distinct styles [26].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Building a Cross-Topic Stylometric Model

This protocol is based on the TDRLM methodology for robust, topic-invariant author verification [25].

- Data Preprocessing: Tokenize texts and perform standard NLP cleaning (lowercasing, removing special characters).

- Topic Modeling: Apply Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) to your training corpus to discover underlying topics.

- Create Topic Score Dictionary: Build a dictionary that records the prior probability of each word (or sub-word token) being associated with a specific topic.

- Model Training: Train the TDRLM model, which integrates the topic score dictionary into a neural network. The model uses a topical multi-head attention mechanism to down-weight topic-biased words during stylometric representation learning.

- Similarity Learning: The model learns to compute a similarity score between two text samples. A threshold is applied to this score to verify if they are from the same author.

- Validation: Test the model on datasets with high topical variance (e.g., social media posts from ICWSM and Twitter-Foursquare) to evaluate cross-topic performance [25].

Protocol 2: Intrinsic Writing Style Separation in a Single Document

This protocol is designed for identifying multiple writing styles within a single document, useful for plagiarism detection or collaboration identification [26].

- Text Chunking: Divide the document into consecutive chunks of a fixed size (e.g., 10 sentences per chunk).

- Feature Extraction: For each chunk, calculate a comprehensive vector of stylometric features. This should include:

- Lexical Features: Average word length, average sentence length, punctuation count.

- Vocabulary Richness: Hapax Legomenon, Yule's Characteristic K, Shannon Entropy.

- Readability Scores: Flesch Reading Ease, Gunning Fog Index [26].

- Dimensionality Reduction: Apply Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to reduce the feature vectors to two dimensions for visualization.

- Clustering: Apply the K-Means algorithm to the feature vectors. Use the Elbow Method to determine the optimal number of clusters (K).

- Visualization and Analysis: Plot the 2D clusters. Chunks grouped in the same cluster are inferred to share the same writing style [26].

Stylometric Feature Tables

Table 1: Core Stylometric Features for Authorship Analysis

Table summarizing key feature categories, specific metrics, and their applications in cross-topic research.

| Category | Key Metrics | Description & Application in Cross-Topic Profiling |

|---|---|---|

| Lexical Diversity [27] [26] | Type-Token Ratio (TTR), Hapax Legomenon Rate, Brunet's W Measure | Measures vocabulary richness and variety. Topic-independent: High-value for cross-topic analysis as they reflect an author's habitual vocabulary range regardless of subject. |

| Syntactic Complexity [27] | Avg. Sentence Length, Complex Verb Count, Contraction Count, Question Count | Captures sentence structure habits. Highly discriminative: Function words and syntactic choices are often unconscious and resilient to topic changes [28]. |

| Readability [27] [26] | Flesch Reading Ease, Gunning Fog Index, Dale-Chall Readability Formula | Quantifies text complexity and required education level. Author Fingerprinting: Can reflect an author's consistent stylistic preference for simplicity or complexity. |

| Vocabulary Richness [26] | Yule's Characteristic K, Simpson's Index, Shannon Entropy | Measures the distribution and diversity of word usage. Robust Signal: Based on statistical word distributions, making them less sensitive to specific topics. |

| Sentiment & Subjectivity [27] | Polarity, Subjectivity, Emotion Word Count, VADER Compound Score | Assesses emotional tone and opinion. Stylistic Marker: The propensity to express emotion or opinion can be a consistent trait of an author. |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of Stylometric Models

Table comparing the performance of different models and feature sets on authorship-related tasks.

| Model / Feature Set | Task | Accuracy / Performance | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| StyloAI (Random Forest) [27] | AI-Generated Text Detection | 81% (AuTextification), 98% (Education) | High interpretability, uses 31 handcrafted stylometric features, effective across domains. |

| TDRLM [25] | Authorship Verification (Cross-Topic) | 92.56% AUC (ICWSM/Twitter-Foursquare) | Superior topical debiasing, excellent for social media with high topical variance. |

| K-Means Clustering [26] | Intrinsic Style Separation | Successful identification of 2 writing styles in a merged document | Unsupervised, requires no pre-labeled training data, effective for single-document analysis. |

| N-gram Models (Baseline) [25] | Authorship Verification | Lower than TDRLM | Simple to implement, but performance suffers from topical bias without debiasing techniques. |

Workflow Diagrams

Diagram 1: Cross-Topic Author Verification Workflow

Diagram 2: Feature Extraction & Style Clustering Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Stylometric Experiments

Key software, libraries, and datasets for conducting cross-topic author profiling research.

| Tool / Resource | Type | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Python NLTK [28] | Software Library | Provides fundamental NLP tools for tokenization, stop-word removal, and basic feature extraction (e.g., sentence/word count). Essential for preprocessing. |

| Scikit-learn [26] | Software Library | Offers implementations of standard machine learning algorithms (e.g., K-Means, Random Forest, PCA) and utilities for model evaluation. |

| Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) [25] | Algorithm | A topic modeling technique used to identify latent topics in a text corpus. Critical for building topic-debiasing models like TDRLM. |

| Federalist Papers [28] | Benchmark Dataset | A classic, publicly available dataset with known and disputed authorship. Ideal for initial testing and validation of authorship attribution models. |

| ICWSM & Twitter-Foursquare [25] | Benchmark Dataset | Social media datasets characterized by high topical variance. Used for stress-testing models on cross-topic authorship verification tasks. |

| StyloAI Feature Set [27] | Feature Template | A curated set of 31 stylometric features, including 12 novel ones for AI-detection. A ready-made checklist for feature engineering. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the key advantages of using a hybrid BERT-LSTM model over a BERT-only model for text classification?

A hybrid BERT-LSTM architecture leverages the strengths of both component technologies. BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) provides deep, contextualized understanding of language semantics [29]. However, incorporating a Bidirectional LSTM (BiLSTM) layer after BERT embeddings allows the model to better capture sequential dependencies and long-range relationships within the text [30]. Research on Twitter sentiment analysis has demonstrated that this combination improves the model's sensitivity to sequence dependencies, leading to superior classification performance compared to BERT-only baselines [30].

FAQ 2: How can we address the "black box" problem and improve model interpretability?

Model interpretability, especially for complex deep learning models, is a significant challenge, often referred to as the "black box" problem [31]. A highly effective solution is the integration of an attention mechanism. By adding a custom attention layer to a BERT-BiLSTM architecture, the model can learn to assign importance weights to different tokens in the input text. Visualizing these attention weights as heatmaps allows researchers to see which words the model "focuses on" when making a decision, such as classifying sentiment. This provides a window into the model's decision-making process and enhances transparency [30].

FAQ 3: Our text data from social media is very noisy. What preprocessing and augmentation strategies are most effective?

Noisy, real-world text data requires robust preprocessing and augmentation. A proven pipeline includes several steps. For preprocessing, handle multilingual content, emojis, hashtags, and user mentions. For data augmentation, particularly to combat class imbalance, techniques like back-translation (translating text to another language and back) and synonym replacement are highly effective [30]. Furthermore, comprehensive text cleaning to remove URLs and standardize informal grammar is crucial for preparing social media data for model training [30].

FAQ 4: What are the common technical challenges when training such deep neural networks, and how can we mitigate them?

Training deep neural networks like BERT-LSTM hybrids presents challenges such as vanishing or exploding gradients, where the learning signal becomes too small or too large as it propagates backward through the network [32]. Modern frameworks and best practices help mitigate these issues. Using well-supported deep learning libraries (e.g., PyTorch, TensorFlow) that employ stable optimization algorithms is key. Furthermore, the widespread availability of pre-trained models like BERT provides a powerful and stable starting point, reducing the need to train models from scratch and lowering the risk of such training instabilities [29].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Model Performance on Specific Text Categories (e.g., Neutral/Irrelevant Tweets)

- Problem: The model achieves high accuracy on "Positive" and "Negative" classes but performs poorly on "Neutral" or "Irrelevant" categories.

- Diagnosis: This is typically caused by class imbalance in the training dataset, where some classes have significantly fewer examples than others.

- Solution:

- Data Analysis: Perform an Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA) to quantify the class distribution.

- Data Augmentation: Apply techniques like back-translation and synonym replacement specifically to the under-represented classes to increase their sample size [30].

- Evaluation: Use metrics like per-class Precision, Recall, and F1-score instead of overall accuracy to get a true picture of model performance across all categories [30].

Issue 2: Model Fails to Generalize to New, Unseen Data

- Problem: The model works well on the validation set but fails in production or on a new batch of data.

- Diagnosis: The model may have overfitted to the training data or the data preprocessing is inconsistent.

- Solution:

- Consistent Preprocessing: Ensure the same text cleaning pipeline (e.g., for URLs, emojis, user mentions) is applied identically to all data, during both training and inference [30].

- Regularization: Employ regularization techniques (e.g., dropout, weight decay) during training to prevent over-reliance on specific features.

- Data Diversity: Verify that the training data is representative of the real-world data the model will encounter, including its multilingual and noisy nature.

Issue 3: High Computational Resource Demands and Long Training Times

- Problem: Training the model is too slow or requires excessive GPU memory.

- Diagnosis: Transformer models like BERT are computationally intensive [29].

- Solution:

- Leverage Pre-trained Models: Start with publicly available pre-trained BERT models and perform only fine-tuning on your specific dataset, rather than training from scratch.

- Transfer Learning: This is the standard practice for using models like BERT. It significantly reduces the data and computational resources required [29] [30].

- Hardware: Utilize GPUs with sufficient VRAM and consider distributed training if necessary.

Experimental Protocols & Data

Quantitative Performance of a BERT-LSTM-Attention Model

The following table summarizes the performance metrics achieved by a hybrid BERT-BiLSTM-Attention model on a multi-class Twitter sentiment analysis task, as documented in recent research [30].

Table 1: Model Performance on Multi-Class Sentiment Analysis [30]

| Sentiment Class | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | > 0.94 | > 0.94 | > 0.94 |

| Negative | > 0.94 | > 0.94 | > 0.94 |

| Neutral | > 0.94 | > 0.94 | > 0.94 |

| Irrelevant | > 0.94 | > 0.94 | > 0.94 |

Detailed Methodology for a Hybrid Model Experiment

Protocol: Implementing a BERT-BiLSTM-Attention Framework for Text Classification

1. Objective: To build a robust and interpretable model for multi-class text classification, suitable for noisy text data like social media posts.

2. Data Preprocessing Pipeline [30]:

* Text Cleaning: Remove or standardize URLs, user mentions, and redundant characters.

* Emoji & Hashtag Handling: Convert emojis to textual descriptions and segment hashtags (e.g., #HelloWorld to "Hello World").

* Multilingual Processing: Ensure the tokenizer supports the languages present in the corpus.

* Data Augmentation:

* Back-translation: Translate sentences to a pivot language (e.g., French) and back to English to generate paraphrases.

* Synonym Replacement: Use a lexical database to replace words with their synonyms for under-represented classes.

3. Model Architecture & Training [30]: * Embedding Layer: Use a pre-trained BERT model to convert input tokens into contextualized embeddings. * Sequence Encoding: Pass the BERT embeddings into a Bidirectional LSTM (BiLSTM) layer to capture sequential dependencies. * Attention Layer: Apply a custom attention mechanism over the BiLSTM outputs to weight the importance of each token. * Output Layer: The attention-weighted representation is fed into a fully connected layer with a softmax activation for final classification. * Training Loop: Fine-tune the model using a cross-entropy loss function and an Adam optimizer.

4. Evaluation: * Use a held-out test set for final evaluation. * Report Precision, Recall, and F1-score for each class to thoroughly assess performance, especially with imbalanced data [30]. * Generate attention weight visualizations (heatmaps) to interpret model decisions.

Model Architecture and Text Preprocessing Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools and Datasets for Cross-Topic Author Profiling

| Research "Reagent" | Type | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-trained BERT Model | Software Model | Provides foundational, contextual understanding of language; serves as a powerful feature extractor [30]. |

| BiLSTM Layer | Model Architecture | Captures sequential dependencies and long-range relationships in text, enhancing semantic modeling [30]. |

| Attention Mechanism | Model Component | Provides interpretability by highlighting sentiment-bearing words and improving classification accuracy [30]. |

| Twitter Entity Sentiment Analysis Dataset | Dataset | A benchmark dataset for training and evaluating model performance on real-world, noisy text [30]. |

| Back-translation Library | Software Tool | A data augmentation technique to increase dataset size and diversity, improving model robustness [30]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is dynamic author profiling, and why is it important for my research?

- A: Dynamic author profiling is the process of automatically characterizing authors (e.g., by demographic, professional role, or psychological traits) from their written texts, particularly in dynamic environments like social media [1] [33]. Unlike static methods, it allows profiles to be updated and new profile dimensions to be defined on-demand without requiring new, manually labeled training data for each new task [33]. This is crucial for cross-topic research and Social Business Intelligence (SBI), where analysis perspectives need to evolve rapidly [33].

Q2: My labeled training data for a new profile category is limited. What are my options?

- A: You can employ an unsupervised, knowledge-based method. This involves using a formal description of the desired user profile and automatically generating a labeled dataset by leveraging word embeddings and ontologies to extract semantic key bigrams from unlabeled text data [33]. This generated dataset can then train your profile classifiers, bypassing the need for manual labeling [33].

Q3: How can I handle polysemy (words with multiple meanings) in author-generated texts?

- A: Consider using adaptive word embedding models like ACWE (Adaptive Cross-contextual Word Embedding). These models generate a global word embedding and then adapt it to create context-specific local embeddings for polysemous words. This improves performance on tasks like word similarity and text classification by better capturing a word's specific meaning in different contexts [34].

Q4: What features are most effective for profiling informal texts from social media?

- A: While simple lexical features (like Bag-of-Words) are common, research shows that emphasizing personal information is highly effective. You can use measures like Personal Expression Intensity (PEI) to select and weight terms that frequently co-occur with first-person pronouns (e.g., "I", "me", "mine"). This has been shown to significantly improve accuracy in age and gender prediction tasks [20]. For bot detection, a set of statistical stylometry features (APSF) used with a Random Forest classifier has proven very successful [35].

Q5: My author profiling model performs well in one domain but poorly in another. How can I improve cross-genre performance?

- A: Cross-genre evaluation is a known challenge [1]. Ensure your training and testing data, while from different genres, are relatively similar for the best results. Focus on robust, domain-agnostic features. The unsupervised method using word embeddings and ontologies is particularly suited for this, as it can generate relevant training data from any text corpus aligned with the target profile dimensions [33].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Classifier Performance on New, User-Defined Profiles

Description: When creating a classifier for a new author profile (e.g., "healthcare influencer"), performance is low due to a lack of labeled training data.

Solution: Implement an unsupervised dataset generation and classification workflow.

Experimental Protocol:

- Multidimensional Model Definition: The analyst first formally defines the new profile classes and their associated semantic concepts using an ontology. For example, the class "Healthcare Professional" could be linked to concepts like

Medicine,Patient Care, andClinical Researchin a domain ontology [33]. - Semantic Key Bigram Extraction: The system processes user descriptions (e.g., Twitter bios) from an unlabeled corpus. It uses the ontology and word embeddings to identify and score key bigrams (two-word sequences) based on their semantic similarity to the predefined profile concepts [33].

- Dataset Generation: User descriptions containing the highest-scoring bigrams are automatically labeled and used to create a silver-standard training dataset. For instance, descriptions containing "pulmonologist" or "clinical trial" would be labeled as "Healthcare Professional" [33].

- Classifier Training: A standard text classifier (e.g., SVM, Random Forest, or a neural network) is trained on this automatically generated dataset [33].

Table: Comparison of Author Profiling Methods

| Method Type | Requires Labeled Data? | Adaptability to New Profiles | Key Strengths | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supervised | Yes, large amounts | Low | High performance on fixed, well-defined tasks | Demographic prediction (age, gender) [1] [20] |

| Unsupervised & Knowledge-Based | No | High | Rapid adaptation, no manual labeling needed | Dynamic SBI, multi-dimensional profiling [33] |

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for this solution:

Problem: Low Accuracy Due to Polysemy in Text

Description: The model misinterprets words with multiple meanings, reducing profiling accuracy.

Solution: Integrate an adaptive word embedding model like ACWE to capture context-specific word senses [34].

Experimental Protocol:

- Global Embedding Training: First, train an unsupervised cross-contextual probabilistic model on a large corpus (e.g., Wikipedia) to obtain a global, unified word embedding for each word [34].

- Local Embedding Adaptation: For a given text, adapt the global embeddings of polysemous words with respect to their local context. This generates different vector representations for the same word tailored to its different meanings [34].

- Feature Integration: Use these context-aware local embeddings as features in your downstream author profiling task, such as text classification [34].

Problem: Ineffective Feature Representation in Social Media Texts

Description: Standard features (e.g., simple word counts) fail to capture the stylistic and personal nuances indicative of an author's profile in informal texts.

Solution: Implement a feature selection and weighting scheme that emphasizes personal expression [20].

Experimental Protocol:

- Identify Personal Phrases: Isolate all sentences in the corpus that contain first-person singular pronouns (I, me, my, mine) [20].

- Calculate Personal Expression Intensity (PEI): For each term in the vocabulary, compute its PEI score. This score combines:

- Personal Precision (ρ): How frequently the term appears in personal phrases versus all phrases.

- Personal Coverage (τ): How often the term appears in personal phrases across different documents [20].

- Feature Engineering:

- Selection: Use the PEI score as a filter to select the most personally expressive terms for your model.

- Weighting: In your document representation (e.g., TF-IDF), boost the weight of terms with a high PEI score [20].

The diagram below shows the logic of emphasizing personal information:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Components for Unsupervised, Knowledge-Based Author Profiling

| Component / Reagent | Function & Explanation | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Domain Ontology | A structured vocabulary of concepts and their relationships. Provides the formal, machine-readable definitions of the target author profiles. | Used to define the "Healthcare Professional" class by linking it to relevant concepts [33]. |

| Pre-trained Word Embeddings | Dense vector representations of words capturing semantic meaning. Used to compute the similarity between user text and ontology concepts. | Models like Word2Vec, FastText, or BERT can be used to score key bigrams [33]. |

| Unlabeled User Corpus | The raw textual data from which profiles will be inferred. Serves as the source for automatic dataset generation. | A collection of user descriptions from Twitter (X) bios or Facebook profiles [1] [33]. |

| Semantic Key Bigram Extractor | The algorithm that identifies and scores relevant two-word phrases based on ontology and embeddings. | This is the core "reagent" that transforms raw text into a labeled dataset [33]. |

| Classification Algorithm | The machine learning model that learns to predict author profiles from the generated features. | Support Vector Machines (SVM) and Random Forests are established, effective choices [1] [35] [33]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core objective of cross-topic author profiling in a research context? The core objective is to build models that can classify authors into predefined profile categories—such as demographics, professional roles, or domains of interest—based on their writing, and to ensure these models can generalize effectively across different topics or domains not seen during training [33].

Q2: Why is data preprocessing so critical for author profiling and similar NLP tasks? Data preprocessing is critical because of the "garbage in, garbage out" principle [36]. Social media and other web-sourced texts are noisy, unstructured, and dynamic [33]. Proper preprocessing, including quality filtering and de-duplication, removes noise and redundancy, which stabilizes training and significantly improves the model's performance and generalization capacity [37].

Q3: We have limited labeled data for our specific author profiles. What are our options? You can employ an unsupervised or minimally supervised method. One approach involves automatically generating high-quality labeled datasets from unlabeled data using knowledge-based techniques like word embeddings and ontologies, based on formal descriptions of the desired user profiles [33]. This can create the necessary training data without extensive manual labeling.

Q4: What are some common feature extraction techniques for representing text? Common techniques include:

- Bag of Words (BoW): Represents text as a matrix of word counts. It is simple but ignores word order and context [38].

- TF-IDF (Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency): Weighs the importance of words by how often they appear in a document versus how common they are across all documents, helping to highlight distinctive terms [38] [39].

- Word/Document Embeddings: Methods like word2vec or BERT create dense vector representations that capture semantic meaning, which can be used for classification or to create document-level embeddings [33].

Q5: How do I choose between a traditional machine learning model and a deep learning model for author profiling? The choice often depends on your data size and task complexity. Traditional models like Naive Bayes, SVMs, or Decision Trees combined with features like TF-IDF are computationally efficient, interpretable, and can be highly effective, especially on smaller datasets [38] [39] [36]. Deep learning models may perform better with very large datasets and can capture complex patterns but require more computational resources [33].

Q6: What does the "double descent" phenomenon refer to in model training? "Double descent" is a phenomenon where a model's generalization error initially decreases, then increases near the interpolation threshold (a point associated with overfitting), but then decreases again as model complexity continues to increase. This challenges the traditional view that error constantly rises with overfitting and highlights the importance of understanding model scaling [37].

Q7: What evaluation metrics should I use for author profiling? While accuracy can be used, it can be misleading for imbalanced datasets. The F1-score, which combines precision and recall, is often a more reliable metric, especially for tasks like sentiment analysis or named entity recognition [38]. For multidimensional profiling, you may need to evaluate performance for each profile class separately.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Model Performance is Poor or Inconsistent

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause 1: Low-Quality or Noisy Training Data

- Solution: Implement a rigorous data preprocessing pipeline.

- Quality Filtering: Use classifier-based or heuristic-based rules to remove low-quality texts. Heuristics can include language-based filtering or removing texts with excessive HTML tags or offensive words [37].

- De-duplication: Perform de-duplication at the sentence, document, and dataset levels to reduce data redundancy, which can harm model generalization and training stability [37].

- Privacy Redaction: Use rule-based methods (e.g., keyword spotting) to remove Personally Identifiable Information (PII) like names and phone numbers to protect privacy and reduce noise [37].

- Solution: Implement a rigorous data preprocessing pipeline.

Cause 2: Ineffective Text Representation

- Solution: Re-evaluate your feature extraction strategy.

- For smaller datasets, try TF-IDF as it is lightweight and interpretable [36].

- If using BoW or TF-IDF, consider applying N-grams (e.g., bigrams or trigrams) to capture local word order and context, which can improve accuracy [38].

- For better semantic understanding, use pre-trained word embeddings (e.g., from Word2Vec, BERT) and fine-tune them on your specific corpus [33].

- Solution: Re-evaluate your feature extraction strategy.

Cause 3: Data Mismatch Between Training and Application Domains

- Solution: Ensure your pre-training data is a balanced mixture of sources. A corpus that is too narrow will not generalize well. Carefully determine the proportion of data from different domains (e.g., web pages, books, scientific texts) in your pre-training corpus to build a robust model [37].

Issue: Handling Class Imbalance in Author Profiles

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: The number of authors in each profile category (e.g., "professional" vs. "individual") is highly unequal.

- Solution:

- Data-Level Methods: Use techniques like oversampling the minority class or undersampling the majority class.

- Algorithm-Level Methods: Use models that can incorporate class weights, which penalize misclassifications of the minority class more heavily.

- Metric Selection: Stop relying on accuracy. Instead, use metrics like F1-score, precision, and recall, which give a better picture of performance on imbalanced data [38]. The following table summarizes these key metrics:

- Solution:

Table 1: Key Evaluation Metrics for Imbalanced Classification

| Metric | Description | Focus | Best for When... |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Percentage of correct predictions overall. | Overall performance | Classes are perfectly balanced. |

| Precision | Proportion of correctly identified positives among all predicted positives. | False Positives | The cost of false alarms is high. |

| Recall | Proportion of actual positives that were correctly identified. | False Negatives | It is critical to find all positive instances. |

| F1-Score | Harmonic mean of precision and recall. | Balance of Precision & Recall | You need a single balanced metric for imbalanced data [38]. |

The relationship between data, model complexity, and this issue can be visualized as follows:

Issue: Implementing a New Author Profile Classifier from Scratch

Solution: Follow this structured workflow for building and validating a model. This integrates the "fit-for-purpose" principle from drug development, ensuring tools are aligned with the specific Question of Interest (QOI) and Context of Use (COU) [40].

Detailed Protocols:

- Define the Multidimensional Model: Formally specify the user profile classes of interest (e.g., "healthcare professional," "academic researcher," "patient advocate") for your analysis [33].

- Data Collection: Gather a substantial amount of natural language corpus from public sources like web pages and conversations. The data should be diverse to improve generalization [37] [33].

- Preprocess Data:

- Quality Filtering: Apply heuristic rules to eliminate low-quality texts based on language, perplexity, or the presence of specific keywords/HTML tags [37].

- De-duplication: Remove duplicate content at sentence, document, and dataset levels to increase data diversity [37].

- Tokenization: Segment raw text into individual tokens. Use a tokenizer like SentencePiece with the BPE algorithm tailored to your corpus for optimal results [37].

- Generate Labeled Dataset (if labeled data is scarce): Use an unsupervised method. Extract semantic key bigrams from analyst specifications and use word embeddings and ontologies to automatically label a dataset of user profiles based on the formal model defined in Step 1 [33].

- Feature Engineering: Transform the cleaned text into numerical features. For a start, use TF-IDF or N-grams [38] [39]. For more advanced applications, use document embeddings generated by methods like weighted averaging of word vectors or fine-tuned transformer models [33].

- Model Training & Validation: Train different classifiers (e.g., Naive Bayes, SVM, Random Forests) and evaluate them using appropriate metrics and validation techniques like cross-validation [38]. The model must be validated against a held-out test set that represents the target domain.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools and Materials for Author Profiling Research

| Item / Solution | Type | Primary Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| spaCy Library | Software Library | Provides industrial-strength NLP for tokenization, lemmatization, POS tagging, and NER [38] [36]. | Preprocessing text descriptions; extracting entities from user bios. |

| NLTK Library | Software Library | A comprehensive platform for symbolic and statistical NLP tasks [39]. | Implementing stemming; using its built-in stopword lists. |

| Scikit-learn | Software Library | Provides efficient tools for machine learning, including TF-IDF vectorization and traditional classifiers [38] [36]. | Building a baseline SVM or Naive Bayes model for profile classification. |

| Word Embeddings (Word2Vec, fastText) | Algorithm/Model | Creates dense vector representations of words that capture semantic meaning [33]. | Generating features that understand that "doctor" and "physician" are similar. |

| BERT & Sentence Transformers | Model/Architecture | Provides deep, contextualized embeddings for words and sentences, achieving state-of-the-art results [33]. | Creating highly accurate document embeddings from user descriptions for classification. |

| Heuristic Filtering Rules | Methodological Protocol | Defines rules to programmatically clean and filter raw text data [37]. | Removing posts with excessive hashtags or boilerplate text during data preprocessing. |

| Genetic Programming | Methodological Framework | Evolves mathematical equations to optimally weight and combine different word embeddings [33]. | Creating a highly tuned document embedding vector for a specific author profiling task. |

Overcoming Pitfalls: Mitigating Bias, Topic Leakage, and Data Imbalance

Identifying and Quantifying Topic Leakage in Test Data

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)