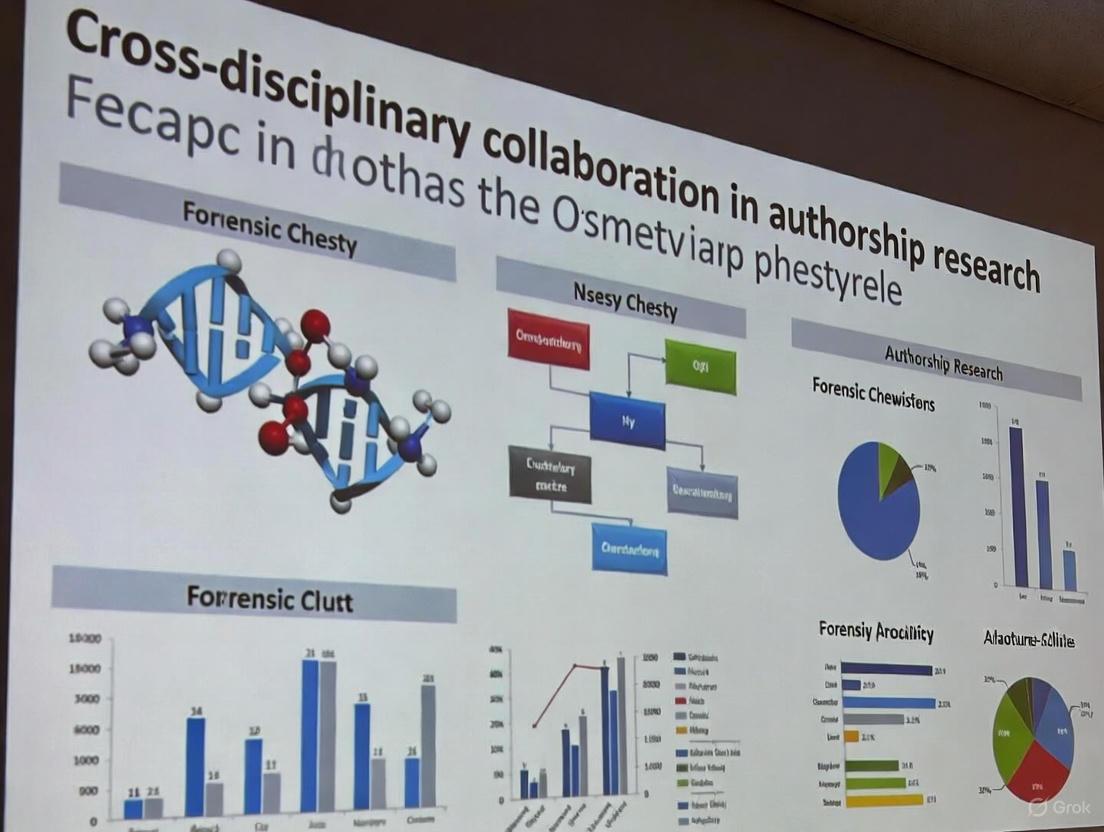

Cross-Disciplinary Collaboration in Research: Strategies, Challenges, and Future Directions

This article explores the critical role of cross-disciplinary collaboration in modern research, particularly within biomedical and drug development contexts.

Cross-Disciplinary Collaboration in Research: Strategies, Challenges, and Future Directions

Abstract

This article explores the critical role of cross-disciplinary collaboration in modern research, particularly within biomedical and drug development contexts. It examines the foundational drivers behind collaborative trends, presents practical methodological frameworks for establishing successful partnerships, addresses common challenges and optimization strategies, and validates effectiveness through case studies and metrics. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this comprehensive review synthesizes current evidence to provide actionable insights for enhancing collaborative research practices and outcomes.

The Rising Tide of Team Science: Understanding Collaborative Research Drivers

The landscape of scientific research is undergoing a profound transformation, characterized by a marked increase in the scale and complexity of collaboration. Cross-disciplinary collaborations have become a central pillar of modern science, essential for tackling pressing global challenges from sustainable food production to drug development [1]. This shift is fundamentally altering the structure of scientific authorship, moving the model away from solitary researchers toward larger, multi-author teams. This paper quantifies this statistical surge in multi-author studies, framing it within the broader context of authorship research and the unique dynamics of cross-disciplinary work. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding the scale, drivers, and implications of this trend is critical for navigating the future of scientific discovery and innovation.

Quantitative Analysis of Multi-Author Trends

Empirical data from a large-scale, international survey provides clear evidence of the rising prevalence of multi-author collaborations and the challenges they bring. A 2023 survey of 752 academics from 41 research fields and 93 countries, which well-represented the overall academic workforce, yielded concerning statistics about the frequency of authorship conflicts [2].

Table 1: Survey Findings on Authorship Conflicts in Academia [2]

| Aspect of Authorship | Statistical Finding | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Prevalence of Conflicts | Conflicts over authorship credit are very common. | Highlights a widespread issue in modern collaborative science. |

| Career Stage of Onset | Conflicts arise very early, at the Master and Ph.D. level. | Indicates that researchers face collaborative challenges from the outset of their careers. |

| Frequency Over Time | Conflicts become increasingly common over time. | Suggests that the challenge grows with career progression and collaboration complexity. |

The survey attributed these conflicts directly to the increasing number of authors listed in publications, a trend that continues to rise steadily [2]. As the number of contributors grows, so does the difficulty in determining both the list of authors to be included in the byline and their respective order, creating multiple potential sources of disagreement.

Experimental Protocols for Analyzing Research Domains and Authorship

To systematically study trends in authorship and collaboration, bibliometric researchers employ rigorous quantitative methodologies. The following protocol outlines a standardized approach for analyzing an individual author's research domain and collaborative output using publication data.

Data Collection and Processing Protocol

- Data Retrieval: Download all available abstracts and metadata for the target author(s) from a comprehensive database such as PubMed. The study by Sung-Ho Jang, Chia-Hung Kao, and Chin-Hsiao Tseng, for example, analyzed 1,388 abstracts from PubMed [3].

- Field Normalization: To define research fields objectively, move beyond journal-based classifications. Instead, use document-level descriptors such as Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms, which provide a rich set of features for clustering research themes [3].

- Matrix Construction: For the article list of each author, develop a two-mode matrix. The rows should represent individual articles, and the columns should represent the MeSH terms associated with those articles. This matrix is the foundation for subsequent network analysis [3].

Social Network Analysis (SNA) and Metric Calculation

- Network Mapping: Use the matrices to perform Social Network Analysis (SNA) with software tools like Pajek. The analysis should be conducted on three distinct sets of data for a comprehensive view [3]:

- Author Articles: The papers published by the author.

- Cited References: The references those author articles cite.

- Citing Articles: The later articles that cite the original author articles.

- Similarity Measurement: Apply bibliographic coupling, a similarity metric based on shared cited references, to determine the similarity in research domain between different pieces of research. Normalize the number of shared references using an index like Salton’s Cosine Index [3].

- Centrality Analysis: Calculate betweenness centrality for nodes within the network. This metric helps identify which MeSH terms or concepts act as the most crucial bridges within the research network, thus defining the core research domain [3].

Achievement and Impact Measurement

- Calculate Bibliometric Indices: Compute indices like the h-index and the adjusted L-index (La-index). The La-index, defined as ( \text{La-index} = \text{round}(ln(\sum{i=1}^{N} \frac{ci}{ai yi} + 1), 0) ) (where (ci) is citations, (ai) is the number of authors, and (y_i) is article age), incorporates the number of co-authors, document age, and citations to classify research achievements [3].

- Visualize Impact: Generate impact beam plots for each author using Relative Citation Ratios (RCRs) over time to visually represent the scientific influence of their body of work [3].

Table 2: Key Reagents and Tools for Bibliometric Analysis

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|

| PubMed / MEDLINE Database | Primary source for retrieving biomedical publication metadata and abstracts. |

| Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) | Standardized vocabulary used to tag and cluster articles by research topic and methodology. |

| Pajek Software | A tool for analyzing and visualizing large networks, used for social network analysis in bibliometrics. |

| Salton's Cosine Index | An algorithm for normalizing and measuring the similarity between two articles based on shared references. |

| Betweenness Centrality Algorithm | A network analysis metric that identifies the most influential nodes (e.g., MeSH terms) in a research network. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow of this experimental protocol, from data collection to final visualization.

Challenges and Best Practices in Cross-Disciplinary Collaboration

The surge in multi-author, cross-disciplinary studies, while beneficial, introduces significant challenges that require proactive management. A primary source of tension is the differing reward models across fields [1]. The culture of publication varies dramatically: the speed from submission to publication can take years in experimental biology versus a much shorter time in theoretical fields; the perceived prestige of journal impact factors is field-dependent; and conventions for author order (e.g., first author as largest contributor, last author as principal investigator) are not universal [1]. These discrepancies can lead to frustration and conflict among collaborators from different disciplines if not discussed and agreed upon early in the project.

Furthermore, terminology and jargon create significant barriers to effective collaboration [1]. Words like "model" can have vastly different meanings to a statistician, a molecular biologist, and a clinician. Success depends on investing time to learn the language of the partner field, asking clarifying questions, and agreeing on a joint nomenclature for the project [1]. Finally, collaborators must practice patience and acknowledge that different fields move at different speeds; the long, arduous timeline of wet-lab experiments cannot be rushed by a computational scientist whose analysis may be completed more quickly [1]. A well-planned publication strategy that accommodates these mismatched timescales is fundamental to a successful collaboration [1].

In an era of increasingly hyperuncertainty, characterized by the rapid onset of multiple, interrelated systemic challenges, societies face a growing category of challenges known as "wicked problems." First coined by planning theorists Horst Rittel and Melvin Webber in the 1970s, this term perfectly captures multi-faceted social problems that are difficult to define, where possible policy solutions have unpredictable and potentially negative repercussions, and about which exist conflicting values [4]. Unlike "tame" problems that may be complicated but have known solutions and processes, wicked problems seem intractable, with no agreed-upon solution or clear cause [5].

The opioid addiction crisis represents a quintessential wicked problem, embodying all these challenging characteristics [4]. Similarly, the obesity epidemic exemplifies a wicked public health challenge that no country has solved despite having evidence-based solutions, with multifaceted causes spanning economic interests, healthcare access, food culture, climate, transportation, ideological differences, and increasing hyperuncertainty from emerging crises [5]. These problems resist traditional linear problem-solving approaches and demand fundamentally different strategies centered on cross-disciplinary collaboration.

Table: Comparing Tame and Wicked Problems

| Characteristic | Tame Problems | Wicked Problems |

|---|---|---|

| Problem Definition | Clear, agreed-upon | Contested, multiple perspectives |

| Solution Path | Known processes and experts | No agreed-upon solution or process |

| Cause-Effect Relationships | Clear and traceable | Unclear, multifaceted causes |

| Stakeholder Alignment | Shared goals and values | Conflicting values and beliefs |

| Examples | Building a hospital | Obesity epidemic, opioid crisis |

The Collaborative Imperative: Beyond Conventional Group Work

Distinguishing Collaboration from Other Approaches

Broad agreement exists that wicked problems require genuine collaboration, yet scholars lament the lack of broad consensus on what specifically distinguishes collaboration from other forms of group work such as coordination or cooperation [5]. Without this common understanding, public health remains limited in its ability to effectively address wicked problems. After synthesizing four decades of scholarship, researchers have identified where consensus is growing around the unique elements required for collaboration [5].

True collaboration differs significantly from other group work approaches in its non-hierarchical structure, member interdependency, and co-ownership of decisions [5]. Where coordination might involve independent entities working in parallel with limited interaction, collaboration requires deep integration of perspectives, resources, and decision-making. This distinction is crucial because using coordination or cooperation when collaboration is needed creates a costly mismatch between the selected approach and the problem at hand [5].

The Framework of Collaborative Advantage

The concept of "collaborative advantage" provides a valuable framework for understanding collaboration's transformative potential. This approach refers to the ability of partners to produce results that are remarkably better than what any single organization could accomplish individually [6]. It recognizes that value is created best through a constellation of organizations and stakeholders working together toward a common purpose.

Collaborative advantage generates three critical outcomes that are essential for addressing wicked problems. First, it improves creativity by bringing together new knowledge, data, and ideas. Second, it realizes innovation by enabling partners to share resources and recombine how they are used to address problems in novel ways. Third, it fosters transformative change by helping organizations reframe their identity and expand their capabilities [6]. These outcomes are supported by three key processes: aligning on a shared purpose, strategically sharing resources, and systematically building trust between partners [6].

Methodological Approaches: Convergence Research and Team Science

Convergence Research in Practice

Convergence research offers an effective approach to tackle wicked problems by integrating diverse epistemologies, methodologies, and expertise [7]. This approach is characterized by its intentional integration of historically distinct disciplines, technologies, and sectors to address particularly challenging problems. Research on drug trafficking activities and counternarcotics efforts demonstrates how convergence research can catalyze catastrophic changes in landscapes and communities through epistemological convergence of diverse data [7].

The process involves three critical integrations. First, epistemological convergence brings together diverse ways of knowing and understanding problems. Second, methodological convergence integrates different research approaches and techniques. Third, political engagement ensures the research remains accountable to multiple affected communities [7]. This approach requires research teams to pursue epistemological and methodological convergence while consciously attending to the inherent politics of producing knowledge about wicked problems.

Experimental Protocols for Cross-Disciplinary Collaboration

Implementing effective convergence research requires structured methodologies. Based on case studies of successful cross-disciplinary teams addressing wicked problems, the following protocols emerge as essential:

Stakeholder Integration Protocol:

- Problem Framing Workshops: Facilitate sessions with all stakeholders to co-define the problem scope

- Epistemological Mapping: Document and visualize different knowledge traditions and their contributions

- Boundary Object Development: Create shared artifacts (models, maps, frameworks) that maintain meaning across disciplines

- Iterative Feedback Loops: Establish regular checkpoints for cross-disciplinary validation

Data Integration Methodology:

- Interoperability Standards: Develop common data standards that respect disciplinary differences

- Translational Interfaces: Create bridging tools that make disciplinary-specific data accessible to all team members

- Collaborative Analysis Sessions: Conduct joint interpretation of integrated datasets

- Validation Across Perspectives: Test findings against multiple disciplinary standards

These protocols help overcome the significant challenges of integrating diverse epistemologies and methodologies, which research teams have identified as major barriers to effective convergence science [7].

Table: Essential Methodologies for Convergence Research

| Methodology | Primary Function | Key Outputs |

|---|---|---|

| Deliberative Public Forums | Engage community and professional stakeholders | Co-created problem definitions, trust building |

| World Café Format | Structured cross-stakeholder dialogue | Identification of shared priorities, community needs |

| Data Interoperability Framework | Integrate diverse data types and sources | Unified datasets for analysis, shared understanding |

| Team Science Protocols | Manage cross-disciplinary collaboration | Effective communication, integrated findings |

Case Study: The Opioid Crisis as a Wicked Problem

From Collaboration to Coproduction

The opioid epidemic exemplifies the wicked problem paradigm, requiring nested collaborative professionals in healthcare, law enforcement, and government working with highly engaged citizens [4]. However, research reveals a critical distinction between collaboration with fellow professionals and collaboration with citizens—a process termed "coproduction" or "doing with" [4]. This distinction highlights how traditional professional collaboration often contains three problematic assumptions: that the wicked problem exists "out there" detached from professional conceptualizations; that institutional flexibility and innovation can solve problems without major institutional changes; and that professionals should lead with citizens invited as helpers [4].

Evidence from public forums on the opioid crisis demonstrates how these assumptions can frustrate citizens who feel sidelined. In Buford Mills (a pseudonym for an Ohio town), forums revealed that citizens wanted more than just supporting roles in professionals' solutions—they desired meaningful voice in problem framing and solving [4]. Comments from professionals often positioned citizens in familiar private-sphere roles (e.g., "value spending time with your children," "lead by example"), while citizens pushed for more substantive involvement like delivering Narcan, forming peer-led anti-drug groups, and participating in community needs assessments [4].

Visualization of Coproduction Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions for Cross-Disciplinary Research

Addressing wicked problems requires both conceptual frameworks and practical tools. The following table details essential "research reagents" – methodological tools and approaches – that facilitate effective cross-disciplinary collaboration.

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Cross-Disciplinary Collaboration

| Research Reagent | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Stakeholder Mapping Tools | Identify and categorize all relevant stakeholders | Initial project scoping, ongoing engagement planning |

| Epistemological Bridge Frameworks | Translate concepts across disciplinary boundaries | Cross-disciplinary team meetings, integrated analysis |

| Deliberative Dialogue Protocols | Structured communication across diverse perspectives | Public forums, stakeholder workshops, team deliberations |

| Data Interoperability Standards | Enable integration of diverse data types | Multi-method research, convergent data analysis |

| Collaborative Governance Structures | Formalize shared decision-making processes | Project management, resource allocation, direction setting |

| Trust-Building Mechanisms | Establish and maintain trust between partners | Partnership initiation, conflict resolution, ongoing collaboration |

| Rapid Feedback Systems | Provide timely input on collaborative processes | Continuous improvement, adaptive management |

Implementation Framework: Navigating Complex Socio-Technical Systems

Adopting a Complexity-Aware Mindset

Complex socio-technical systems present particular challenges for addressing wicked problems. As Don Norman notes, these systems are difficult to define, complex, difficult to know how to approach, and difficult to know whether a solution has worked [8]. The human brain, evolutionarily designed for simple cause-effect chains, struggles with the multiple feedback loops and long delays between actions and results that characterize these systems [8].

This complexity demands humanity-centered design approaches that differ from traditional problem-solving methods. Effective strategies include using people-centered design to tap a population's insights, solving the right problem through in-depth consideration, seeing everything as a system using systems thinking, and taking small, simple steps toward sustainable solutions through incremental modular design [8]. Big problems may seem to demand big solutions, but large interventions are often too expensive, disruptive, and prone to failure—making pragmatic, small-scale approaches more effective [8].

Simulation and Adaptive Learning Frameworks

In healthcare contexts, which exemplify complex socio-technical systems, simulation-based interventions provide valuable frameworks for addressing wicked problems. A three-component conceptual framework has proven effective for navigating this complexity: (1) thorough problem identification, (2) contextually appropriate simulation design, and (3) multifaceted evaluation strategies [9]. These components function across organizational levels, supporting a dynamic and adaptive approach to addressing system challenges.

Healthcare simulation exemplifies how to integrate Complex Adaptive Systems and Resilient Healthcare principles into practical interventions. This approach fosters a complexity-aware mindset, enabling healthcare professionals and organizations to anticipate, respond to, and recover from challenges more effectively [9]. Rather than isolated training events, simulation becomes a complex intervention that operates across levels and responds to dynamic system needs, bridging theory and practice while fostering more adaptive and resilient systems [9].

Wicked problems such as the opioid crisis, obesity epidemics, and climate change resist traditional siloed approaches precisely because they are embedded in complex systems with multiple interacting elements. Solving these challenges requires genuine collaboration that goes beyond mere coordination or cooperation to create new, integrated approaches that leverage diverse expertise.

The path forward requires institutional commitment to building collaborative capacity through developing shared languages across disciplines, creating structures that support convergence research, and adopting complexity-aware approaches that acknowledge the limitations of traditional linear problem-solving. By embracing collaborative advantage, coproduction with affected communities, and adaptive learning frameworks, researchers and practitioners can develop more effective responses to the wicked problems that define our era of hyperuncertainty.

True progress will come not from seeking definitive solutions to these inherently wicked problems, but from building resilient, adaptive systems of collaboration that can continuously learn and respond to evolving challenges across disciplinary, professional, and community boundaries.

The prevailing trend in scientific discovery is characterized by a profound paradox: as individual researchers delve deeper into specialized domains, the solutions to complex, frontier-pushing problems increasingly demand the integration of knowledge from across disciplinary boundaries. This paradigm shift from solitary investigation to collaborative synthesis is not merely a logistical convenience but a fundamental requirement for generating transformative insights. Research in the "science of team science" has begun to identify specific practices that underpin effective and productive collaborative teams, moving beyond anecdotal evidence to provide a empirical foundation for building successful interdisciplinary groups [10]. This guide provides a technical and methodological framework for constructing and managing these broader teams, ensuring that deep specialization becomes a catalyst for synthesis rather than an obstacle to innovation.

The necessity for this approach is particularly acute in fields like drug development, where challenges span from target identification and preclinical research to clinical trials and market implementation. No single specialist can possess the depth of knowledge required across biochemistry, pharmacology, computational modeling, regulatory science, and clinical medicine to shepherd a compound from concept to clinic. Success depends on creating a whole that is greater than the sum of its expertly specialized parts.

Quantitative Foundations: Measuring the Impact of Synthesis

The efficacy of cross-disciplinary collaboration is supported by quantitative metrics across multiple dimensions. The following tables synthesize key findings from team science research, providing a structured overview of the measurable benefits and operational requirements for successful synthesis teams.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Cross-Disciplinary Research Teams

| Metric Category | Specific Measure | Impact of Effective Collaboration | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Publication Output | Number of publications | Increased output in high-impact journals [10] | Longitudinal team tracking |

| Citation count | Higher average citations per publication [10] | Citation index analysis | |

| Research Quality | Novelty of concepts | Higher integration of disparate knowledge domains [10] | Concept linkage analysis |

| Methodological rigor | Enhanced through complementary expert review [10] | Protocol assessment | |

| Career Development | Early career inclusion | Accelerated professional development and network expansion [10] | Career trajectory surveys |

| Co-authorship patterns | More equitable distribution of authorship roles [10] | Authorship contribution analysis |

Table 2: Operational Requirements for Synthesis Teams

| Team Characteristic | Optimal Configuration | Quantitative Benchmark | Measurement Tool |

|---|---|---|---|

| Team Composition | Disciplinary diversity | 3-5 distinct technical fields represented [10] | Skills matrix inventory |

| Data Management | Data set harmonization | 15-20 hours/week during initial phase [10] | Project time tracking |

| Meeting Frequency | Full team engagement | Bi-weekly for core members [10] | Momentum metrics |

| Communication | Tool utilization | ≥3 complementary platforms (e.g., Slack, GitHub) [10] | Usage analytics |

| Authorship Clarity | Contribution definition | 100% alignment on CRediT taxonomy [10] | Pre-publication agreement |

Experimental Protocols for Cross-Disciplinary Synthesis

Protocol 1: Team Formation and Composition

Objective: To construct a cross-functional research team with optimal diversity of expertise while maintaining effective communication dynamics.

Methodology:

- Needs Assessment: Map the core research question against required knowledge domains. Prioritize fields that provide complementary, not redundant, methodologies (e.g., pair a community ecologist with a biostatistician rather than another community ecologist) [10].

- Recruitment: Extend recruitment beyond immediate professional networks. Proactively engage researchers from undergraduate or minority-serving institutions to access diverse perspectives and talent pools [10].

- Skills Matrix Development: Create a visual mapping of team competencies versus project requirements. Identify critical gaps that require additional recruitment or training.

- Social Contract Establishment: Facilitate a team-wide discussion to establish explicit norms for communication, decision-making, and conflict resolution prior to initiating research activities.

Protocol 2: Data Sourcing and Harmonization

Objective: To identify, acquire, and standardize disparate data sets for integrated analysis.

Methodology:

- Requirements Scoping: Prior to data search, explicitly define the variables, spatial/temporal scales, and metadata completeness required to address the research question [10].

- Systematic Discovery: Implement a structured data search protocol across repositories (e.g., EDIA, GenBank, clinical trial registries) using standardized query terminology [10].

- Provenance Documentation: Maintain a dynamic inventory of all data sources, including access dates, versioning, and constraints on use. This is critical for reproducibility and ethical compliance [10].

- Harmonization Pipeline: Develop scripted workflows (e.g., in R or Python) to normalize variables, resolve unit conflicts, and align data structures. Version-control all harmonization scripts using platforms like GitHub [10].

Protocol 3: Facilitation Through the "Groan Zone"

Objective: To navigate the inevitable period of conceptual dissonance in interdisciplinary work where team members struggle to integrate disparate frameworks.

Methodology:

- Anticipatory Guidance: Educate team members that the "groan zone"—a period of confusion and stalled progress—is a normal, productive phase of synthesis rather than a sign of failure [10].

- Structured Dialogue: Employ facilitation techniques such as "brainwriting" or round-robin sharing to ensure equitable airtime and prevent dominant personalities from controlling the discourse.

- Conceptual Translation: Create visual concept maps that explicitly link terminology and frameworks from different disciplines, highlighting areas of overlap and dissonance.

- Progress Validation: Acknowledge and celebrate small conceptual breakthroughs to maintain morale and momentum through challenging integration phases [10].

Visualization Frameworks for Collaborative Synthesis

Effective visualization is critical for making the structure and dynamics of collaborative research tangible. The following diagrams, generated using Graphviz DOT language, provide conceptual maps for understanding and planning synthesis teams.

Diagram 1: Knowledge Integration in Cross-Disciplinary Synthesis

Diagram 2: Synthesis Research Data Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful collaboration requires both conceptual frameworks and practical tools. The following table details essential "research reagents" for cross-disciplinary synthesis, spanning technical platforms and methodological approaches.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Collaborative Synthesis

| Tool Category | Specific Solution | Function in Synthesis Research | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Communication Platforms | LTER Slack [10] | Enables real-time discussion of conceptual challenges and quick questions outside formal meetings. | Dedicated channels for specific sub-teams (e.g., #datawrangling, #manuscriptdraft). |

| Shared email lists [10] | Ensures critical updates reach all members; digest options prevent inbox overload. | Automated meeting summaries and decision points distributed via list. | |

| Project Management Systems | GitHub Projects [10] | Version-controlled task management with assignable duties and progress tracking. | Scripted analysis workflows with issue tracking for bug reports and enhancements. |

| Trello [10] | Visual task boards suitable for teams less familiar with programming environments. | Mapping the manuscript writing process from outline to submission. | |

| Reproducible Workflow Tools | R/Python Scripting [10] | Creates documented, repeatable analyses that can be audited and extended by team members. | Data harmonization pipeline that transforms raw datasets into analysis-ready formats. |

| GitHub Versioning [10] | Tracks evolution of code and documents; enables parallel workstreams without conflict. | Branching structure for developing multiple analysis approaches simultaneously. | |

| Collaborative Writing Aids | CRediT Taxonomy [10] | Standardized framework for defining and acknowledging authorship contributions transparently. | Pre-publication checklist completed by all authors to determine author order. |

| Simplified Authorship Template [10] | Structured document for early discussion of authorship expectations and roles. | Draft template completed during project kickoff to prevent future conflicts. | |

| Computing Infrastructure | High-performance analytical servers [10] | Provides computational power for large-scale data synthesis and modeling. | Running complex ecological simulations that integrate climate, soil, and species data. |

| Shared document wikis [10] | Centralized knowledge repository for meeting notes, protocols, and conceptual frameworks. | Living document that captures evolving understanding of integrated concepts. |

Discussion: Navigating the Synthesis Lifecycle

The journey from deep specialization to transformative synthesis follows a predictable yet challenging lifecycle. Teams must initially invest significant time in establishing shared mental models and a common lexicon, deliberately navigating the conceptual dissonance that arises when disciplines with different paradigms converge. This initial investment pays substantial dividends during the analysis and interpretation phase, where diverse perspectives enable the team to identify patterns and connections that would remain invisible within a single disciplinary lens.

Critical to sustaining momentum through this lifecycle is the proactive management of authorship expectations. The CRediT framework provides a valuable standardized taxonomy for discussing and documenting contributions, helping to preempt conflicts that can derail collaborative projects [10]. Furthermore, teams should establish clear protocols for data management and archiving early in the process, as derived data products from synthesis research must often be made publicly available to fulfill funding requirements and ethical imperatives [10].

The most successful synthesis teams embrace both the technical and social dimensions of collaboration. They recognize that specialized knowledge represents not just technical facility but also distinct ways of thinking, and they create environments where these cognitive differences can interact productively. By implementing the structured protocols, visualization frameworks, and toolkits outlined in this guide, research teams can transform the paradox of specialization into the engine of innovation.

In a world defined by complex global challenges, cross-border partnerships have emerged as a critical mechanism for advancing human knowledge and developing innovative solutions. The ability to collaborate beyond national boundaries is no longer a luxury but a necessity, particularly in fields such as biomedical research and drug development where the scale of problems often exceeds the capacity of any single nation or institution. The production of knowledge increasingly transcends national borders, thriving in an interconnected global scientific ecosystem where effective collaboration is key to pushing the frontiers of innovation and maximizing economic and societal impact [11].

The digital transformation of recent years has fundamentally reshaped the possibilities for international scientific cooperation, introducing a suite of technological enablers that overcome traditional barriers of distance, jurisdiction, and resource distribution. This whitepaper examines the core digital enablers facilitating these partnerships, focusing specifically on their application within cross-disciplinary authorship research and drug development contexts. Through quantitative analysis, methodological frameworks, and visual mapping of collaborative workflows, we provide researchers and scientific professionals with a comprehensive understanding of how technology is redefining the boundaries of scientific cooperation.

Quantitative Landscape of Cross-Border Research

Understanding the current state of cross-border research collaboration requires examining quantitative evidence across multiple domains. The data reveals both significant progress and notable disparities in how different regions and fields engage in international scientific partnerships.

Bibliometric Analysis of Collaborative Research

A systematic review of PubMed-indexed studies from 2018-2022 provides compelling evidence of growing research collaboration, though with distinct geographical patterns. The analysis of 1,084 studies utilizing anonymized biomedical data revealed a statistically significant yearly increase of 2.16 articles per 100,000 when normalized against total PubMed-indexed articles (p = 0.021) [12]. This trend persisted even when excluding COVID-19 related research, indicating a fundamental shift toward data-intensive international collaboration.

Table 1: Geographical Distribution of Studies Using Anonymized Biomedical Data (2018-2022)

| Region/Country | Percentage of Studies | Normalized Ratio (per 1000 citable documents) | Cross-Border Sharing Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States (US) | 53.1% | 0.545 | 10.5% |

| United Kingdom (UK) | 18.2% | 0.387 | 10.5% |

| Australia | 5.3% | 0.254 | 10.5% |

| Continental Europe | 8.7% | 0.061 | 10.5% |

| Asia | Not specified | 0.044 | 10.5% |

| Global Average | 100% | 0.157 | 10.5% |

The data reveals striking geographical disparities, with Core Anglosphere countries (US, UK, Canada, Australia) demonstrating the highest rates of anonymized data sharing for research, with an average of 0.345 articles per 1000 citable documents compared to just 0.061 in Continental Europe and 0.044 in Asia [12]. This suggests that regulatory frameworks, cultural attitudes toward data sharing, and research infrastructure significantly influence participation in data-driven cross-border research.

Structural and Economic Dimensions

Beyond biomedical research, cross-border collaboration manifests in economic and structural forms with distinct growth patterns. The North American cross-border e-commerce market, representing one facet of digital economic integration, demonstrates remarkable expansion with a projected compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 28.7% from 2024 to 2031, rising from USD 316,616.88 million in 2024 [13]. This commercial digital integration creates underlying infrastructure that supports research collaborations through streamlined procurement, knowledge exchange, and resource sharing.

The scientific impact of these collaborations is substantiated by citation analysis, with Elsevier reporting that internationally co-authored articles demonstrate 52% higher scientific impact than the global average [14]. At leading institutions like Tecnológico de Monterrey, international co-authorship rates reach 50%, significantly exceeding the OECD average of nearly 20% for research articles worldwide [14].

Digital Enablers: Technical Frameworks and Implementation

Cross-border research partnerships rely on a sophisticated ecosystem of digital technologies that enable secure collaboration, data sharing, and joint analysis. This section details the core technological frameworks and their implementation protocols.

Cross-Border Data Sharing Architectures

The foundation of modern cross-border research is secure data exchange that balances accessibility with appropriate privacy protections. Several architectural approaches have emerged as standards for international research collaborations.

Anonymization Technical Protocols The traditional approach to privacy-preserving data sharing involves technical anonymization processes that alter data to significantly reduce the risk of it being traced back to individuals [12]. The implementation follows specific technical protocols:

- De-identification Framework: Implementation of the Safe Harbor method as defined by the HIPAA Privacy Rule, requiring removal of 18 specified identifiers including names, geographic subdivisions smaller than a state, and dates directly related to an individual [12].

- Statistical Anonymization: Application of statistical methods including k-anonymity (ensuring each individual is indistinguishable from at least k-1 others), l-diversity (ensuring sensitive attributes have at least l well-represented values), and differential privacy (adding calculated noise to query responses) [12].

- Federated Learning Systems: Implementation of distributed machine learning approaches where model training occurs across multiple decentralized edge devices or servers holding local data samples without exchanging them [12].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Digital Collaboration

| Solution Category | Specific Technologies | Research Application | Technical Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Privacy-Enhancing Technologies | Differential Privacy, Federated Learning, Synthetic Data Generation | Biomedical data analysis, Clinical trial collaboration | Enables data analysis without raw data exchange, preserves statistical utility while protecting privacy |

| Cross-Border Data Platforms | E-Government Knowledgebase & Analytics Platform (EKAP), European Health Data Space (EHDS) | Policy research, Public health studies, Multi-center trials | Provides multilingual digital platforms for knowledge sharing, standardizes data access protocols |

| Collaborative Research Networks | Universitas 21, Association of Pacific Rim Universities (APRU) | Multi-disciplinary research, Global health initiatives | Creates trusted environments for resource sharing, joint funding proposals, institutional bonding |

| Regulatory Sandboxes | Digital Regulatory Sandbox (UN-UAE Initiative) | Emerging technology policy, Regulatory science | Provides controlled testing environments for innovative technologies across jurisdictional boundaries |

Implementation Challenges and Solutions Despite technological advances, significant barriers impede cross-border data sharing. The analysis reveals cross-border sharing occurs in only 10.5% of studies using anonymized data [12]. This limitation stems from regulatory fragmentation, with differing legal frameworks such as HIPAA in the US, NHS guidance in the UK, and the ambiguous definition of anonymization in the EU creating compliance complexities [12]. The emerging European Health Data Space (EHDS) regulation aims to address these obstacles by providing additional legal bases for sharing biomedical data on an opt-out basis [12].

Digital Governance and Measurement Frameworks

Effective cross-border partnerships require robust governance structures and measurement approaches that can operate across jurisdictional boundaries. The United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA), in partnership with the United Arab Emirates, has developed a comprehensive digital cooperation framework spanning 2025-2029 with three strategic work streams [15].

Digital Regulatory Sandbox Implementation The regulatory sandbox component provides a controlled environment for testing innovative technologies and approaches across participating countries (United Arab Emirates, Jordan, Lebanon, Tunisia) [15]. The implementation protocol includes:

- Identification Phase: Multi-stakeholder workshops at regional and national levels to identify policy gaps and opportunities

- Conceptualization Phase: Country-specific studies and strategy notes for operationalizing sandboxes

- Implementation Phase: Study visits and policy guidance toolkits for practical deployment

- Scale-up Phase: Global and regional dialogue for replication across additional countries

E-Government Measurement Model The project includes development of a next-generation E-Government Measuring Model (EMM) that aligns with cutting-edge digital governance trends [15]. This model provides actionable insights for policymakers through:

- Updates to EGDI-related indicators including the Online Service Index (OSI) and Local Online Service Index (LOSI)

- Regional and global consultations to ensure scalability and relevance

- Advanced analytics capabilities for comprehensive assessment of digital governance readiness

Payment and Resource Flow Systems

Cross-border research collaborations require efficient mechanisms for financial transactions and resource allocation across jurisdictions. Research on Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) countries has identified distinct archetypes for payment system adoption that influence research collaboration efficiency [16]:

- Digital Pioneers: Characterized by high technological infrastructure and cultural acceptance of digital solutions

- Regulatory Harmonizers: Driven primarily by policy alignment rather than technological advancement

- Institutional Trust Builders: Focused on governance improvements to facilitate transactions

- Hybrid Adopters: Employing selective integration based on specific use cases and partnerships

The Cross-Border Payment Adoption Index (CPAI) developed in this research measures payment system maturity across technological, regulatory, institutional, and cultural dimensions, providing a framework for predicting integration paths [16]. This is particularly relevant as digital currencies begin to reshape the international research funding environment.

Technological Workflows for Cross-Border Collaboration

The integration of digital enablers follows defined workflows that facilitate cross-border research partnerships from initiation through to implementation and impact assessment.

Diagram 1: Cross-Border Research Partnership Workflow. This diagram illustrates the phased approach to establishing and maintaining international research collaborations, highlighting critical decision points and feedback mechanisms.

The workflow emphasizes the iterative nature of cross-border partnerships, with continuous feedback informing subsequent collaborative cycles. This approach aligns with initiatives like Science Europe's Weave framework, which supports excellent international research projects through streamlined administrative processes and funding alignment [11].

Case Studies in Cross-Border Partnership Implementation

UN-UAE Digital Cooperation Initiative (2025-2029)

This five-year initiative represents a comprehensive approach to digital cross-border cooperation, targeting Arabic-speaking countries in Western Asia and North Africa through three strategic work streams [15]:

Digital Regulatory Sandbox: Enhancing institutional capacity for policy experimentation and regulatory innovation in new technologies through practical solution implementation.

E-Government Knowledgebase & Analytics Platform (EKAP): Developing a multilingual digital knowledge sharing platform with integrated self-assessment capabilities for member states.

E-Government Measuring Model (EMM): Creating a next-generation assessment model tailored to current e-government trends for accurate measurement of digital governance dimensions.

The project directly addresses capacity building for policymakers and civil servants while creating infrastructure for ongoing regional cooperation in digital governance [15].

Global North-South Research Bridge

Tecnológico de Monterrey has established a collaborative model that connects Global North research excellence with Global South regional expertise and implementation capacity. The partnership with the Ragon Institute of Boston's Mass General Brigham health system, MIT, and Harvard demonstrates how strategic alliances can accelerate discovery and deployment of innovative solutions [14]. This model integrates top-tier research capabilities with regional know-how, creating a template for connecting Latin America to global research centers of excellence.

The collaboration moves beyond traditional mobility-based internationalization toward deeper institutional integration, leveraging collective strengths through shared resources, knowledge exchange, and impact amplification [14]. This approach addresses the UN Pact for the Future's call for enhanced support from the Global North to assist the Global South in climate action, technology transfer, and capacity-building [14].

Future Directions and Implementation Recommendations

Based on analysis of current digital enablers and their applications in cross-border partnerships, several key recommendations emerge for researchers, scientific institutions, and policymakers:

Develop Adaptive Regulatory Frameworks: Regulatory approaches must balance privacy protection with research accessibility. The success of anonymized data sharing in Core Anglosphere countries suggests that clear, practical guidelines like HIPAA's Safe Harbor method facilitate cross-border research more effectively than ambiguous standards [12].

Invest in Interoperable Digital Infrastructure: The limited cross-border data sharing (10.5% of studies) despite increasing research collaboration highlights the need for technically compatible systems across jurisdictions [12]. Initiatives like the European Health Data Space represent important steps toward interoperable frameworks [12].

Align Financial Systems with Research Needs: As digital currencies and payment systems evolve, research collaborations require efficient cross-border transaction mechanisms. The Cross-Border Payment Adoption Index provides a valuable tool for assessing and improving financial infrastructure to support international research [16].

Strengthen Institutional Partnership Models: Successful collaborations like the UN-UAE initiative and Tec-Ragon Institute partnership demonstrate that moving beyond simple MOUs to deeply integrated strategic alliances generates significantly greater impact [15] [14]. These require alignment of expectations, complementary value propositions, and committed resources.

Address Geographical Imbalances: The significant disparities in research participation between Core Anglosphere countries and other regions highlight the need for targeted capacity-building initiatives, particularly in Continental Europe, Asia, and the Global South [12] [14].

Digital technologies have fundamentally transformed the possibilities for cross-border research partnerships, providing the technical infrastructure necessary to overcome traditional barriers of distance, jurisdiction, and resource distribution. From privacy-enhancing technologies that enable secure data sharing to collaborative platforms that facilitate joint analysis and discovery, these digital enablers are expanding the frontiers of scientific cooperation.

The quantitative evidence demonstrates both significant progress and persistent challenges. While international co-authorship produces research with 52% higher impact than the global average [14], substantial geographical disparities in participation remain [12]. Addressing these imbalances requires concerted effort to develop interoperable systems, harmonized regulations, and equitable partnerships.

For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding and leveraging these digital enablers is no longer optional but essential for participating at the cutting edge of scientific discovery. The frameworks, workflows, and case studies presented in this whitepaper provide a roadmap for building effective, sustainable cross-border partnerships that can address the complex challenges facing our interconnected world.

Building Bridges: Practical Frameworks for Successful Cross-Disciplinary Partnerships

The complexity of contemporary scientific challenges, from cancer research to public health crises, necessitates a fundamental shift from traditional, siloed approaches toward integrative, problem-based frameworks. Organ-system thinking, while valuable for deepening knowledge within specialized domains, often proves insufficient for addressing multifaceted problems that span biological scales and scientific disciplines. Cross-disciplinary research explores uncharted territories at the boundaries of established scientific fields, where the most important scientific progress occurs [17]. This paradigm does not merely sum up contributions from different fields but integrates them to create novel solutions and insights that are impossible to achieve within a single discipline [17]. Problem-based approaches provide the essential structure to focus this cross-disciplinary integration on pressing real-world challenges, fostering an environment where computational biologists, clinicians, physicists, and engineers can collaborate to generate transformative knowledge. The restructuring of research toward such models is recognized as key to finding solutions to pressing, global-scale societal challenges, including drug development [1].

Defining the Paradigm: From Multidisciplinary to Cross-Disciplinary Research

A critical distinction exists between multidisciplinary and cross-disciplinary research. In a multidisciplinary setting, specialists from different fields work on their respective parts of a problem independently, with limited interaction—akin to a multicultural environment where different cultures coexist [17]. In contrast, cross-disciplinary research is a melting pot where new cultures emerge, enriched by various contributions [17]. It involves exploring uncharted territories at the boundaries of established scientific fields, often leading to the creation of entirely new fields such as Bioinformatics, Environmental Sciences, and Computational Social Sciences [17].

This cross-disciplinary approach is fundamental to problem-based research. It focuses on the problem itself, rather than the confines of any single discipline, requiring the development of a shared language and the breaking down of disciplinary silos [1] [17]. For instance, a physicist might seek universal mechanisms, while a biologist focuses on the diversity of living organisms, and even a basic term like "model" can have vastly different meanings across fields [1] [17]. Successfully navigating these differences demands creativity, negotiation, compromise, and open-mindedness from all collaborators [17].

Implementing Problem-Based Cross-Disciplinary Frameworks

Institutional and Collaborative Structures

Effective cross-disciplinary research requires innovative organizational models that replace traditional pyramidal structures with more fluid and integrative frameworks. A decentralized institutional structure, without fixed, separate research groups, fosters the necessary environment for collaboration [17]. Leadership should be collaborative, with decision-making processes that emphasize consensus and inclusivity [17]. The research environment itself should function as a self-organized complex system composed of nodes (researchers) that interact through scientific dialogue and transversal structures [17].

Key practical rules for successful cross-disciplinary collaboration include:

- Learning the Language: Different fields have distinct terminologies. Forming a successful relationship requires learning the other field's jargon early on and agreeing on a joint nomenclature for the project [1].

- Understanding Different Paces: Research in fields like experimental biology can involve long, arduous experiments, while computational aspects might proceed more quickly. Patience and clear communication about timelines are vital [1].

- Aligning Reward Models: Publication culture, including publication speed, journal impact factors, and author ordering conventions, varies significantly between fields. Discussing and planning a publication strategy early is crucial to avoid frustration [1].

Educational Underpinnings: Cultivating the Next Generation of Researchers

The successful implementation of problem-based, cross-disciplinary research depends on cultivating a new generation of scientists equipped with the necessary skills and mindset. Hybrid Problem-Based Learning (hPBL) models, which blend traditional Lecture-Based Learning (LBL) with Problem-Based Learning (PBL), have proven effective in this regard [18].

Table 1: Assessment Outcomes for Hybrid Problem-Based Learning (hPBL) in Molecular Biology Education

| Assessment Domain | hPBL Group Performance | LBL (Control) Group Performance | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Final Assessment Score | Significantly Superior | Lower | P < 0.05 |

| Theoretical Knowledge | 91.82 ± 2.25 | 87.69 ± 3.99 | P < 0.001 |

| Clinical Practice Assessment | 92.25 ± 2.04 | 88.19 ± 2.23 | P < 0.001 |

| Self-learning Capability | Effectively Amplified | Less Amplified | Not Reported |

| Practical Application Skills | Effectively Amplified | Less Amplified | Not Reported |

| Student Satisfaction | High Degree | Lower | Not Reported |

As shown in Table 1, the hPBL model demonstrates significant benefits. In a study on medical molecular biology experimental courses, the hPBL group outperformed the LBL control group across multiple domains, including theoretical knowledge, clinical practice, and the development of self-learning and practical application skills [18]. This model follows a three-stage learning approach (pre-class pre-study, in-class discussion, post-class review) that integrates PBL discussion into classroom lectures guided by a teacher [18]. Furthermore, the integration of computational thinking into PBL frameworks further enhances creative problem-solving skills, encouraging students to decompose complex problems, recognize patterns, and design algorithmic solutions [19].

A Framework for Cross-Disciplinary Research in Drug Development

Applying a problem-based, cross-disciplinary framework to drug development requires a systematic methodology that integrates diverse expertise from the outset. The following workflow and toolkit outline a structured approach.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Technologies

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Cross-Disciplinary Drug Development

| Reagent / Technology | Core Function | Application in Problem-Based Context |

|---|---|---|

| 3D Organoid Cultures | Physiologically relevant in vitro models that recapitulate key aspects of human tissue and disease. | Provides a more predictive platform for evaluating drug efficacy and toxicity beyond 2D cell lines, bridging molecular biology and clinical pharmacology. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing Systems | Precision tools for targeted genome modification. | Enables functional validation of drug targets and the creation of disease models for complex pathologies, integrating molecular biology with computational genomics. |

| High-Throughput Screening (HTS) Assays | Automated technologies for rapidly testing thousands of compounds against a biological target. | Generates large-scale data for hypothesis generation and lead compound identification, requiring close collaboration between biologists, chemists, and data scientists. |

| AI-Powered Drug Design Platforms | Computational systems using machine learning to predict compound properties and optimize lead molecules. | Accelerates the drug discovery process by integrating chemical data with biological activity readouts, a core collaboration between computational and medicinal chemistry. |

| Multi-Omics Profiling Technologies | Integrated analysis of genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics data. | Provides a systems-level view of disease mechanisms and drug responses, demanding expertise from biology, bioinformatics, and biostatistics. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: An Integrated Workflow for Target Validation

This protocol exemplifies a cross-disciplinary, problem-based approach to validating a novel therapeutic target identified through genomic studies.

I. Problem Decomposition and Team Assembly

- Objective: To validate the functional role of "Gene X" in a specific disease pathway and assess its druggability.

- Team: Assemble a core team comprising a clinical researcher (provides patient insights and samples), a molecular biologist (designs wet-lab experiments), a computational biologist (analyzes omics data and models pathways), and a medicinal chemist (assesses target druggability).

II. Integrated Experimental and Computational Workflow

- Clinical Data Analysis & Target Identification:

- Method: Analyze patient genomic and transcriptomic datasets to identify "Gene X" as a potential driver of disease pathology.

- Output: A prioritized list of candidate genes and associated biological pathways.

- In Vitro Functional Validation:

- Method: Utilize CRISPR-Cas9 in relevant cell lines (e.g., primary cells or organoids) to knock out (KO) or knock down (KD) "Gene X".

- Assays: Measure phenotypic consequences using:

- Viability Assays (ATP-based luminescence).

- Migration/Invasion Assays (Boyden chamber).

- Transcriptomic Profiling (RNA-seq) of KO vs. control cells.

- Output: Functional data linking "Gene X" to disease-relevant phenotypes.

- Computational Modeling & Druggability Assessment:

- Method: Perform structural modeling of the protein product of "Gene X" to identify potential binding pockets.

- Method: Conduct virtual screening of compound libraries against the modeled structure.

- Output: A shortlist of predicted small-molecule binders and an assessment of the protein's "druggability".

- Iterative Refinement and Data Integration:

- Method: Test the computationally prioritized compounds in the phenotypic assays from Step 2.

- Feedback Loop: Use the experimental results from compound testing to refine the computational model for subsequent rounds of virtual screening.

III. Data Integration and Analysis

- Objective: Correlate findings from all workflows to build a cohesive evidence package for target validation.

- Action: The computational biologist integrates the RNA-seq data, phenotypic data, and compound activity data to build a network model of "Gene X" function and its perturbation by lead compounds. This integrated model forms the basis for deciding whether to progress the target to further development.

The movement beyond organ-system thinking toward problem-based, cross-disciplinary approaches is not merely an academic exercise but a fundamental necessity for advancing modern drug development and biomedical research. This paradigm shift leverages integrative frameworks to tackle complex biological problems that defy traditional siloed approaches. Success hinges on both innovative institutional structures that foster collaboration and educational models that equip scientists with the necessary integrative skills. By embracing these frameworks, the research community can accelerate the translation of scientific discovery into transformative therapies for patients. The future of biomedical innovation lies in our ability to connect disciplines, share languages, and focus collectively on the problem at hand.

In cross-disciplinary authorship research, particularly within drug development, the complexity of challenges demands structured collaborative frameworks. These frameworks are essential for integrating diverse expertise from biology, chemistry, computational science, and clinical research to accelerate innovation and navigate the intricate path from discovery to market. This whitepaper examines three pivotal collaborative design models—Common Base, Common Destination, and Sequential Link—detailing their operational paradigms, experimental protocols, and applications in scientific research. The analysis is framed within a broader thesis on cross-disciplinary collaboration, highlighting how these models facilitate the breaking down of disciplinary silos, a challenge prominently noted in large-scale research initiatives [1]. By providing a structured comparison and methodological toolkit, this guide aims to equip researchers and drug development professionals with the knowledge to select and implement the most appropriate collaborative framework for their specific research challenges.

The three models facilitate cross-disciplinary integration through distinct mechanisms and structural relationships. The table below provides a comparative summary of their core characteristics.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Collaborative Design Models

| Feature | Common Base Model | Common Destination Model | Sequential Link Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Multiple disciplines work from a shared foundational resource or knowledge pool [20]. | Diverse teams align efforts toward a unified, overarching goal [21]. | Outputs from one disciplinary group become inputs for the next in a defined sequence [20]. |

| Structural Analogy | Hub-and-Spoke | Converging Pathways | Assembly Line or Relay Race |

| Primary Coordination Mechanism | Centralized resource management and continuous negotiation [20]. | Goal-oriented planning and mediated alignment [21]. | Pre-defined hand-off protocols and interface specifications [20]. |

| Ideal Application Context in Research | Early-stage discovery, data-heavy fields requiring a "single source of truth" [22]. | Large, mission-oriented projects like drug development for a specific disease [21]. | Projects with clear, stage-gated workflows and well-defined disciplinary inputs [23]. |

The theoretical underpinnings of these models are rooted in inter-organisational collaboration theory, which examines the antecedents, processes, and barriers to joint work [21]. The Common Base Model leverages the concept of boundary objects—shared artifacts like standardized data formats or a central model-based definition (MBD) that are robust enough to maintain common identity across disciplines but flexible enough to adapt to local needs [24] [22]. The Common Destination Model is often explained through stakeholder theory, where a Destination Collaborator (e.g., a project lead or organization) works to align the interests, goals, and expectations of all parties toward a shared outcome, managing power imbalances and resource competition [21]. The Sequential Link Model aligns with network theory, focusing on the strength and configuration of ties between sequential nodes (teams) and the criticality of clear hand-off protocols to prevent errors and delays [20] [23].

The Common Base Model

Core Principles and Workflow

The Common Base Model operates on the principle that a centrally maintained, authoritative resource serves as the foundation for all collaborative work. In drug development, this could be a unified biological model, a central data repository for omics data, or a shared pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic (PK-PD) model. This model effectively breaks down barriers by creating a "single source of truth," which is crucial for ensuring consistency and accuracy across multidisciplinary teams [22]. A key enabler is the individual capacity to switch between solving tasks within one's own discipline and jointly solving tasks with other professionals, fostering a shared understanding [24].

The diagram below illustrates the flow of information and collaboration in this model.

Experimental Protocol: Establishing a Common Base for Target Identification

This protocol outlines the methodology for creating a shared knowledge base for early-stage drug target identification.

- Objective: To integrate heterogeneous data sources into a unified, accessible knowledge base to enable cross-disciplinary hypothesis generation for novel drug targets.

- Materials and Methods:

- Data Curation: Assemble data from public repositories (e.g., GenBank, Protein Data Bank, GEO) and internal experiments (e.g., genomics, proteomics, high-throughput screening). Standardize all data into a common format (e.g., using ISA-TAB standards) to ensure interoperability [1].

- Base Platform Setup: Implement a centralized database or knowledge graph platform (e.g., based on PostgreSQL or a graph database like Neo4j). The schema should be co-designed by bioinformaticians, biologists, and chemists to capture relevant entities and relationships.

- Model Integration: Embed established computational models (e.g., protein-ligand docking scores, pathway models) into the platform as accessible services, allowing for dynamic querying and simulation.

- Access and Interaction: Provide a web-based interface or API for researchers to query, visualize, and annotate the common base. Usage should be tracked to understand collaboration patterns.

- Expected Outputs: A live, queryable knowledge base; a set of newly generated, data-driven target hypotheses; a log of cross-disciplinary queries and annotations.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for the Common Base Model

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|

| Standardized Data Format (e.g., ISA-TAB) | Provides a unified framework for describing experimental data, enabling integration from diverse sources and ensuring consistency [1]. |

| Centralized Database (e.g., PostgreSQL, Neo4j) | Serves as the physical instantiation of the Common Base, allowing for secure storage, complex queries, and management of large-scale biological data. |

| Model-Based Definition (MBD) Platform | Acts as a "single source of truth" for integrated models and data, fostering clarity and precision among all stakeholders [22]. |

| API (Application Programming Interface) | Allows different software tools and disciplines to programmatically interact with the Common Base, enabling automation and custom analysis. |

The Common Destination Model

Core Principles and Workflow

This model is defined by a shared, overarching goal that orchestrates the activities of multiple, often parallel, disciplinary tracks. In drug development, the "common destination" is typically a clearly defined clinical or regulatory milestone, such as the demonstration of efficacy in a Phase II trial or New Drug Application (NDA) approval. Collaboration is facilitated by a mediating entity, such as a project leadership team or a Destination Management Organization (DMO) in other fields, which aligns efforts and manages resources [21]. Success relies on individual enablers like curiosity about other professions and motivation to engage in cross-disciplinary processes [24].

The following diagram visualizes the convergence of parallel efforts toward a shared goal.

Experimental Protocol: Coordinating a Preclinical to Clinical Transition

This protocol describes a coordinated, cross-functional effort to achieve the destination of Investigational New Drug (IND) application submission.

- Objective: To successfully integrate data from chemistry, manufacturing, controls (CMC), pharmacology, and toxicology studies to compile and submit a complete IND package to a regulatory agency.

- Materials and Methods:

- Destination Scoping: The project leadership team clearly defines the IND submission requirements, timeline, and quality criteria. This plan is communicated to all functional teams.

- Parallel Track Execution:

- CMC Team: Works on synthetic route scaling, formulation development, and analytical method validation.

- Pharmacology/Toxicology Team: Conducts GLP studies to establish a safety profile and mechanism of action.

- Clinical Team: Designs the Phase I clinical trial protocol.

- Mediated Synchronization: Hold regular cross-functional team meetings chaired by project leadership. The agenda focuses on progress against milestones, interdependencies, and problem-solving (e.g., a stability issue impacting the toxicology study supply).

- Integrated Document Assembly: A regulatory writing team collaborates with all functional leads to draft the IND modules, ensuring a cohesive narrative that seamlessly integrates data from all parallel tracks.

- Expected Outputs: A submitted IND application; a documented history of cross-functional issue resolution; a refined protocol for future destination-oriented projects.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for the Common Destination Model

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|

| Project Charter & Goal Document | Formally defines the "Common Destination" (e.g., IND submission), its scope, and success criteria, ensuring all teams are aligned from the outset. |

| Shared Timeline & Milestone Map | A visual tool (e.g., a Gantt chart) that displays the parallel tracks of work and their critical interdependencies toward the common goal. |

| Cross-Functional Meeting Framework | A structured protocol for regular meetings (e.g., agile sprints, stand-ups) that facilitates mediated synchronization and issue escalation [23]. |

| Integrated Document Management Platform | A central repository (e.g., a SharePoint site or regulatory submission platform) for assembling, reviewing, and version-controlling the final deliverable. |

The Sequential Link Model

Core Principles and Workflow

The Sequential Link Model organizes collaboration as a linear or stage-gated process, where the output of one specialized team becomes the direct input for the next. This model is prevalent in established workflows where deep, specialized work is required at each stage. The primary challenge is managing the "hand-off" between sequences, which requires clear deliverables and communication to avoid the propagation of errors, as famously seen in the Airbus A380 wiring incident due to incompatible software versions [23]. Collaboration is facilitated by project management that coordinates meetings and activities for hand-offs [24].

The workflow of this model is depicted in the diagram below.

Experimental Protocol: A Stage-Gated Lead Optimization Cascade

This protocol outlines a sequential process for optimizing a initial "hit" compound into a development candidate.

- Objective: To systematically progress a hit compound through a series of defined, specialized evaluations to select a preclinical candidate with desired potency, selectivity, and pharmacokinetic properties.

- Materials and Methods:

- Stage 1 - In Vitro Potency & Selectivity (Biochemistry Team):

- Input: A collection of hit compounds from a screen.

- Process: Determine IC50 against the primary target and counter-screens against related targets to assess selectivity.

- Deliverable: A prioritized list of compounds with >100x selectivity.

- Stage 2 - Cellular Efficacy (Cell Biology Team):

- Input: The prioritized compound list from Stage 1.

- Process: Test compounds in cell-based assays to confirm target engagement and functional activity (e.g., inhibition of pathway phosphorylation).

- Deliverable: Compounds with demonstrated cellular efficacy (EC50 < 1 µM).

- Stage 3 - In Vitro ADME (DMPK Team):

- Input: Compounds from Stage 2.

- Process: Assess metabolic stability in liver microsomes, permeability (Caco-2), and cytochrome P450 inhibition.

- Deliverable: Compounds with favorable in vitro ADME properties.

- Stage 4 - Preliminary In Vivo PK (In Vivo Pharmacology Team):

- Input: The top 2-3 compounds from Stage 3.

- Process: Conduct a single-dose pharmacokinetic study in rodents to estimate exposure and half-life.

- Deliverable: A final candidate molecule with acceptable projected human pharmacokinetics.

- Stage 1 - In Vitro Potency & Selectivity (Biochemistry Team):

- Expected Outputs: A nominated preclinical development candidate; a comprehensive data package for the candidate; a documented decision trail for each stage-gate.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents for the Sequential Link Model

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|

| Standardized Hand-off Protocol | A formal template specifying the required data format, quality controls, and acceptance criteria for deliverables passed from one stage to the next, preventing miscommunication [1]. |

| Stage-Gate Decision Document | A formal checklist used by project leadership to review deliverables from one stage and grant approval to proceed and allocate resources to the next. |

| Compatible Software Suites | Ensures data and model compatibility across sequences (e.g., using the same version of CAD/CATIA software or data analysis platforms) to avoid integration failures [23]. |

| Automated Data Pipeline | Scripts or software that automatically transfer and reformat output data from one stage to the input requirements of the next, reducing manual errors and speeding up the cycle. |

In modern drug development and authorship research, breakthrough innovations increasingly occur at the intersection of specialized disciplines. This cross-disciplinary collaboration presents a fundamental challenge: specialists with deeply embedded thought worlds, scientific practices, and communication patterns must find common ground to advance shared objectives [25]. The terminology and conceptual frameworks that provide precision within a discipline can become significant barriers when collaborating across domains. Effective translation—the accurate and context-aware interpretation of concepts, methods, and findings—becomes the critical enabler for successful collaboration.

The consequences of translation failures are not merely theoretical. In drug discovery, for instance, teams consistently in flux must navigate unpredictable findings and emerging obstacles that require continuous modification of team composition and communication strategies [25]. Without effective translation mechanisms, domain-specific successes fail to advance collective goals. This technical guide provides frameworks, methodologies, and evidence-based practices for establishing the shared terminology essential for cross-disciplinary success in research collaboration.

The Conceptual Framework: Understanding Cross-Disciplinary Translation

Defining the Translation Spectrum

In collaborative research, "translation" extends beyond linguistic conversion to encompass conceptual alignment across disciplinary boundaries. This spectrum includes:

- Linguistic Translation: Converting written or spoken content between languages while preserving scientific meaning, as required when research involves multiple language contexts [26].

- Conceptual Translation: Interpreting discipline-specific terminology, models, and methodologies for specialists from other fields while maintaining scientific integrity [25].

- Knowledge Translation: Transforming research findings across the continuum from basic discovery to practical application, exemplified by the "bench-to-bedside" paradigm in translational medicine [27].

Interdisciplinarity Versus Transdisciplinarity

Understanding the nature of collaboration is essential for effective translation:

- Multidisciplinary Approaches involve multiple disciplines working side-by-side in a parallel but separate manner, with translation occurring primarily at interfaces [28].