Comparative Investigation of Spectroscopic Behavior in Different Atmospheres: From Fundamental Principles to Biomedical Applications

This comprehensive review explores the critical influence of atmospheric conditions on spectroscopic measurements across chemical, environmental, and biomedical domains.

Comparative Investigation of Spectroscopic Behavior in Different Atmospheres: From Fundamental Principles to Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores the critical influence of atmospheric conditions on spectroscopic measurements across chemical, environmental, and biomedical domains. By synthesizing recent research advances, we examine fundamental light-matter interactions in various environments, methodological innovations in atmospheric-controlled spectroscopy, strategies for troubleshooting measurement inaccuracies, and rigorous validation approaches. The article highlights how controlled atmospheric environments significantly enhance detection accuracy, particularly for UV-active species and high-concentration solutions, while addressing challenges in spatially resolved measurements and aerosol characterization. For researchers and drug development professionals, these insights provide essential guidance for optimizing spectroscopic protocols, improving measurement reliability in process monitoring, and advancing biomedical imaging techniques including metabolic tracking and tissue analysis.

Fundamental Principles: How Atmospheric Conditions Alter Light-Matter Interactions

Theoretical Framework of Atmospheric Effects on Spectral Measurements

Atmospheric spectroscopy utilizes the interaction between light and atmospheric constituents to remotely sense and quantify environmental properties. This comparative guide examines how different atmospheric conditions—from pristine polar regions to dust-laden air masses—affect spectral measurements across various spectroscopic techniques. The fundamental principle involves analyzing how gases, aerosols, and other atmospheric components absorb, scatter, and fluoresce when exposed to specific wavelengths of light. These interactions create distinctive spectral signatures that can be decoded to determine atmospheric composition [1] [2].

Understanding atmospheric effects on spectral measurements is crucial for multiple applications: climate modeling, air quality monitoring, satellite validation, and source attribution of pollution events. Different atmospheric conditions introduce distinct challenges and considerations for spectroscopic measurements, requiring specialized approaches for data collection, processing, and interpretation. This guide systematically compares these atmospheric effects across key spectroscopic methodologies, providing researchers with a framework for selecting appropriate techniques based on their specific atmospheric measurement challenges.

Fundamental Atmospheric Processes Affecting Spectral Measurements

Key Interaction Mechanisms

Atmospheric spectral measurements are influenced by several fundamental physical processes that modify light transmission. Absorption occurs when specific atmospheric gases (e.g., CO₂, O₂, O₃, H₂O) absorb photons at characteristic wavelengths, creating identifiable absorption lines in spectra [3] [1]. Elastic scattering (Rayleigh and Mie) redirects light without altering its wavelength, affecting signal intensity but not spectral distribution. Fluorescence represents a particularly informative process where certain atmospheric particles absorb light at one wavelength and re-emit it at longer wavelengths, providing valuable information about biological components and certain types of pollution [4] [2].

The interplay of these processes creates the complex spectral signatures detected by ground-based, airborne, and satellite instruments. The relative dominance of each mechanism depends on multiple factors including wavelength region, atmospheric composition, viewing geometry, and instrument characteristics. Understanding these fundamental interactions provides the foundation for interpreting spectral data across different atmospheric conditions.

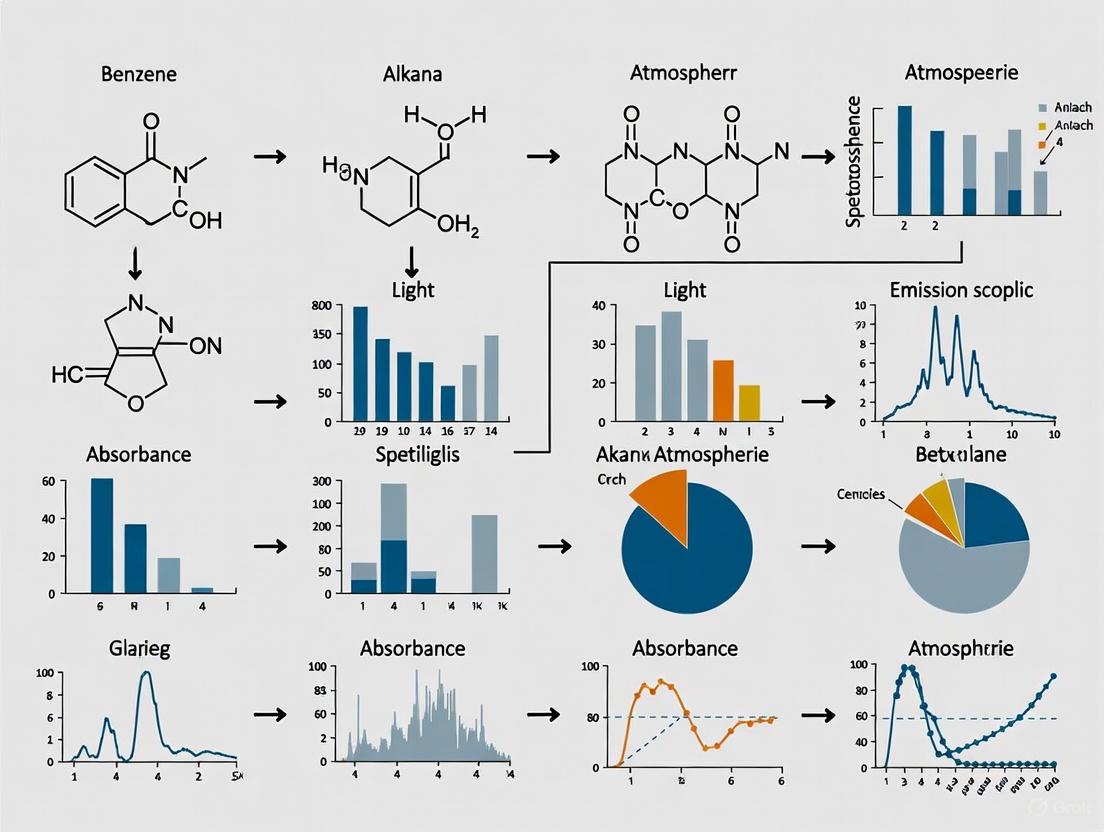

Diagram: Atmospheric Effects on Spectral Measurements

The diagram below illustrates how light interacts with various atmospheric components during spectroscopic measurements, showing the different physical processes that modify the original signal.

Comparative Analysis of Measurement Techniques

Instrumentation and Methodologies

Different spectroscopic techniques have been developed to address specific atmospheric measurement challenges, each with distinct advantages and limitations depending on atmospheric conditions. This comparison covers the primary approaches used in contemporary atmospheric research.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Atmospheric Spectroscopy Techniques

| Technique | Primary Applications | Atmospheric Targets | Key Advantages | Typical Precision/Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Differential Optical Absorption Spectroscopy (DOAS) | Trace gas monitoring, aerosol characterization | O₄, NO₂, SO₂, H₂O, aerosols | Well-defined light path, temperature-resistant measurements | O₄ cross-section accuracy: <2% [1] |

| Lidar with Fluorescence Detection | Bioaerosol detection, aerosol-cloud interactions | Fluorescing aerosols, biomass burning particles, dust | Spectral discrimination of aerosol types, vertical profiling | Fluorescence capacity: 10⁻⁶–10⁻⁵ nm⁻¹ [2] |

| Satellite-Based Retrieval (Full-Physics) | Greenhouse gas monitoring, global scale observations | CO₂, CH₄, aerosol optical depth | Global coverage, long-term data records | XCO₂ accuracy: 0.5–4 ppm [3] |

| Machine Learning Retrieval | Efficient processing of large spectral datasets | CO₂ from satellite spectra | Computational efficiency, rapid processing | XCO₂ accuracy: ~3 ppm [3] |

| Multi-Axis DOAS (MAX-DOAS) | Aerosol property retrieval, vertical distribution | Aerosol extinction, cloud properties | Multiple scattering information, vertical profiling | Aerosol optical depth uncertainty: ~10% [1] |

Atmospheric Condition-Specific Considerations

Different atmospheric conditions present unique challenges for spectral measurements, requiring specialized approaches for accurate data interpretation across varied environments.

Dust-Laden Atmospheres: Mineral dust, particularly from Saharan sources, exhibits distinctive fluorescence signatures characterized by spectra skewed toward shorter wavelengths with maxima below 500 nm and a linear decrease in spectral backscatter at longer wavelengths. The fluorescence capacity remains low (<1×10⁻⁶ nm⁻¹), providing a clear differentiation from other aerosol types. African dust transport events show unmistakable bioaerosol-like fluorescing particles that can be associated with dust episodes based on their spectral signatures [4] [2].

Biomass Burning Aerosols (BBA): BBA displays rounded fluorescence spectra with maxima between 500-550 nm when excited at 355 nm, with high spectral fluorescence capacity (up to >9×10⁻⁶ nm⁻¹). Spectral changes with height include increasing Gaussian shape and general red-shift toward longer wavelengths, though opposite dependencies (blue-shift) occur in specific cases, indicating chemical aging or different source characteristics [2].

Urban/Polluted Atmospheres: Urban environments feature complex spectral interference from multiple gases (NOx, O₃, NMHC) exhibiting periodic variations driven by both terrestrial and extraterrestrial factors. Studies in Riyadh revealed 10-584 day cycles in atmospheric gases, with solar activity (F10.7 flux) driving NOx and NMHC photochemistry (r=0.50, p<0.01), while cosmic rays showed correlation with O₃ (r=0.30, p<0.01) and negative correlation with NOx/NMHC [5].

Pristine Environments: Measurements in Antarctica demonstrate the advantage of minimal aerosol interference for fundamental cross-section validation. LP-DOAS measurements at Neumayer Station confirmed laboratory O₄ absorption cross-sections at 360 nm under temperatures ranging from -45°C to +5°C, with best agreement for Finkenzeller and Volkamer (2022) cross-sections [1].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Measurement Approaches

Consistent experimental protocols are essential for comparative atmospheric spectroscopy across different conditions and locations. The following methodologies represent current best practices in the field.

Long-Path DOAS Measurements: The LP-DOAS technique employs an artificial light source (xenon arc lamp or laser-driven light source) and a well-defined light path ranging from 1-5 km. The instrument at Neumayer Station, Antarctica, utilized a 1.55 km or 2.95 km light path with retro-reflectors, spectral resolution of approximately 0.54 nm covering a 65 nm window, and temporal resolution of 2-30 minutes. Analysis focused on the 352-387 nm window for O₄ absorption at 360 nm, with temperature and pressure recorded continuously [1].

Fluorescence Lidar Protocols: The RAMSES instrument at Lindenberg, Germany, employs a frequency-tripled Nd:YAG laser (354.7 nm, 30 Hz, 15 W average power) with careful suppression of fundamental and second-harmonic generation light. The receiver system combines Newtonian (300 mm) and Nasmyth-Cassegrain (790 mm) telescopes with three spectrometers covering 378-458 nm (UVA), 385-410 nm (water), and 440-750 nm (VIS). Fluorescence spectra are obtained by merging data from UVA and VIS spectrometers, with absolute calibration following Reichardt (2012) methodology [2].

Satellite Retrieval Algorithms: Full-physics retrieval for greenhouse gases employs iterative optimization where atmospheric radiative transfer is modeled to simulate observed spectra, with inverse methods optimizing input parameters to minimize differences between modeled and observed spectra. The two-step machine learning approach offers computational advantages by first retrieving atmospheric spectral optical thickness, then deriving CO₂ column density from the optical thickness spectrum [3].

Diagram: Atmospheric Spectral Measurement Workflow

The diagram below outlines the generalized workflow for conducting and analyzing atmospheric spectral measurements, from experimental design through data interpretation.

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Successful atmospheric spectral measurements require specialized instrumentation, calibration standards, and analysis tools. This section details the essential components for establishing capable atmospheric spectroscopy capabilities.

Table 2: Essential Research Tools for Atmospheric Spectroscopy

| Category | Specific Tools/Standards | Function/Purpose | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Field Instruments | Wideband Integrated Bioaerosol Spectrometer (WIBS) | Individual particle sizing (0.5-30 µm), shape factor, fluorescence typing | African dust bioaerosol transport studies [4] |

| Spectrometric Fluorescence Lidar (RAMSES) | Vertical profiling of aerosol fluorescence spectra (378-750 nm) | Biomass burning aerosol characterization [2] | |

| Long-Path DOAS System | Accurate path-averaged trace gas measurements with defined light path | O₄ absorption cross-section validation [1] | |

| Reference Data | Laboratory O₄ Absorption Cross-Sections | Reference spectra for atmospheric radiative transfer modeling | Aerosol and cloud property retrievals [1] |

| HITRAN Database | Line parameters for atmospheric gas absorption | Forward model calculations for greenhouse gas retrievals [3] | |

| Analysis Tools | Back-trajectory Models (HYSPLIT) | Air mass history determination for source attribution | Connecting aerosol properties to source regions [4] |

| Radiative Transfer Models (VLIDORT) | Simulation of light propagation in atmosphere | Satellite retrieval algorithm development [3] | |

| Calibration Standards | Absolute Calibration Methods | Spectrometric lidar calibration without external references | Fluorescence spectrum quantification [2] |

| TCCON Station Data | Ground-truth validation for satellite CO₂ retrievals | XCO₂ algorithm validation [3] |

Data Interpretation and Analytical Framework

Quantitative Spectral Analysis Parameters

The interpretation of atmospheric spectral data relies on specific quantitative parameters that enable comparison across different conditions and instruments. For fluorescence measurements, the spectral fluorescence capacity has emerged as a key intensive parameter, similar to the lidar fluorescence ratio, which enables aerosol typing by normalizing fluorescence intensity to particle concentration [2]. For absorption spectroscopy, the differential slant column density represents the integrated concentration of absorbers along the light path, derived through spectral fitting procedures that remove broadband contributions [1].

Statistical analyses of atmospheric spectral data often reveal complex relationships. For BBA fluorescence, correlations with atmospheric state variables are relatively weak, with ambient temperature showing the best correlation among state variables, and particle depolarization ratio correlating best among elastic-optical properties [2]. Periodic behavior in urban atmospheric gases demonstrates the influence of both terrestrial and extraterrestrial factors, with Lomb periodogram analysis revealing significant cycles ranging from 10 days to 1.6 years driven by meteorological patterns, solar rotation (27-day cycle), and semi-annual oscillations [5].

Comparative Performance Across Atmospheric Conditions

The performance of spectroscopic techniques varies significantly across different atmospheric conditions, requiring careful consideration of these factors in experimental design and data interpretation. Satellite-based aerosol optical depth (AOD) retrievals from the ATSR-SLSTR instrument series demonstrate better performance over dark surfaces and oceans compared to bright land surfaces, with ongoing algorithm improvements to address these limitations [6]. Fluorescence lidar measurements show distinctive spectral characteristics for different aerosol types: BBA exhibits rounded fluorescence spectra with maxima at 500-550 nm and high fluorescence capacity, while Saharan dust shows spectra skewed to shorter wavelengths with maxima below 500 nm and low fluorescence capacity [2].

Atmospheric temperature and pressure effects significantly impact spectral measurements, particularly for absorption cross-sections that display temperature dependence. O₄ absorption cross-sections at 360 nm show increased peak cross-section and decreased band width at colder temperatures, with the integral cross-section increasing with temperature based on the most recent laboratory measurements [1]. These temperature dependencies must be incorporated into radiative transfer models for accurate atmospheric retrievals across different altitude ranges and seasonal conditions.

This guide provides an objective comparison of spectroscopic performance in air versus nitrogen atmospheres, supporting a broader thesis on spectroscopic behavior. It is designed for researchers and drug development professionals requiring accurate analytical data.

Experimental Protocols for Spectroscopic Analysis in Different Atmospheres

The following section details the core methodologies used to generate the comparative data in this guide, based on a foundational study investigating atmospheric effects.

1.1 Core Experimental Setup The comparative investigation was conducted using a UV-visible spectrophotometer. The key experimental modification involved installing a gas-tight assembly that allowed the instrument's optical path to be purged with either a nitrogen atmosphere or an air atmosphere for direct comparison. All measurements were performed at a constant optical path length of 5 mm to ensure consistency across all samples [7].

1.2 Sample Preparation and Analysis The study selected four target substances with characteristic absorption across different electromagnetic regions:

- Deep Ultraviolet (180-200 nm): SO₄²⁻ (sulfate) solutions.

- Ultraviolet (200-300 nm): S²⁻ (sulfide) solutions.

- Visible (300-500 nm): Ni²⁺ (nickel ion) solutions.

- Near-Infrared (600-900 nm): Cu²⁺ (copper ion) solutions. Solutions were prepared across a range of concentrations, and their absorption intensities were measured in both atmospheric conditions. The relationship between concentration and absorption intensity (C-A curve) was established for each substance under both air and nitrogen [7].

Comparative Performance Data: Air vs. Nitrogen Atmosphere

The data below summarizes the quantitative impact of atmospheric conditions on spectroscopic detection accuracy and sensitivity.

Table 1: Impact of Atmosphere on Spectroscopic Detection Accuracy

| Target Substance | Characteristic Wavelength Region | Key Observed Effect of Nitrogen vs. Air Atmosphere | Quantitative Improvement (Relative Error, RE) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SO₄²⁻ (Sulfate) | Deep Ultraviolet (180-200 nm) | Effective improvement in accuracy; suppression of red shift; increased sensitivity [7]. | RE < 5% within standard range [7]. |

| S²⁻ (Sulfide) | Ultraviolet (200-300 nm) | Improved accuracy by isolating oxygen, which absorbs UV light [7]. | Not explicitly quantified, but significant [7]. |

| Ni²⁺ (Nickel Ion) | Visible (300-500 nm) | No significant change in the slope of the C-A curve [7]. | Negligible [7]. |

| Cu²⁺ (Copper Ion) | Near-Infrared (600-900 nm) | No significant change in the slope of the C-A curve [7]. | Negligible [7]. |

Table 2: Summary of Atmospheric Interference Mechanisms

| Atmosphere | Impact on UV Region (<240 nm) | Impact on Visible/NIR Region | Overall Effect on Detection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Air | Significant interference due to oxygen absorption, causing additional light attenuation [7]. | Negligible interference [7]. | Reduced accuracy and sensitivity for substances absorbing in the UV region [7]. |

| Nitrogen | Isolates oxygen, suppressing additional UV attenuation [7]. | Negligible interference [7]. | Improved accuracy and sensitivity for UV-absorbing substances; baseline flatness is improved [7]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key materials and their functions for conducting controlled atmosphere spectroscopy.

Table 3: Essential Materials for Spectroscopic Analysis in Controlled Atmospheres

| Item / Reagent | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| UV-Visible Spectrophotometer | Core instrument for measuring the absorption of light by samples across ultraviolet and visible wavelengths [7]. |

| Nitrogen Gas Supply | Provides an inert, oxygen-free atmosphere to purge the spectrophotometer's optical path, eliminating UV absorption by oxygen [7]. |

| Gas-Tight Sample Assembly | Customizable chamber or enclosure that allows for purging with protective gases like nitrogen without leaking [7]. |

| SO₄²⁻, S²⁻, Ni²⁺, Cu²⁺ Standards | High-purity solutions used to establish calibration curves and validate method performance under different atmospheres [7]. |

| PTFE Filter Media | Used in offline aerosol sampling (e.g., via UAS) to collect particles for subsequent chemical analysis [8]. |

Workflow and Scientific Rationale

The following diagrams illustrate the experimental process and the underlying scientific principles of atmospheric interference.

Experimental Workflow for Atmospheric Comparison

Mechanism of Atmospheric Interference in Spectroscopy

Discussion of Findings

The experimental data reveals a clear distinction: the benefit of a nitrogen atmosphere is highly specific to the ultraviolet region. For substances like Ni²⁺ and Cu²⁺ in the visible and near-infrared spectra, no significant improvement was observed, as oxygen absorption is not a confounding factor in these regions [7].

For UV-absorbing substances, particularly SO₄²⁻, the nitrogen environment provided a dual benefit. Primarily, it suppressed the additional light attenuation caused by oxygen, leading to more accurate absorption measurements and improved sensitivity, as evidenced by the steeper slope of the C-A curve [7]. A secondary observation was the suppression of the red shift in the characteristic wavelength of SO₄²⁻ at high concentrations [7].

The research indicates that for high-concentration solutions, the intermolecular forces between analyte groups become a significant factor affecting detection accuracy, with an influence potentially greater than that of oxygen absorption. The interaction between SO₄²⁻ groups reduces the energy required for electron excitation per unit, leading to non-linearity in the C-A curve at high concentrations [7]. This insight is critical for the direct detection of high-concentration solutions in process industries, enabling more sustainable industrial development and cleaner production practices [7].

Ultraviolet (UV) spectroscopy is a fundamental analytical tool across scientific disciplines, from environmental monitoring to pharmaceutical development. Its principle relies on measuring the absorption of UV light by molecules as they undergo electronic transitions. However, the accuracy of this technique, particularly in the short-wave ultraviolet region, is significantly compromised by a often-overlooked factor: the presence of molecular oxygen (O₂) in the optical path [9]. This guide provides a comparative investigation of spectroscopic behavior in air versus inert nitrogen (N₂) atmospheres, detailing the molecular mechanisms of oxygen interference, its quantifiable impact on analytical performance, and practical methodologies for its mitigation.

The core issue stems from the inherent electronic structure of molecular oxygen. O₂ possesses characteristic absorption bands within the UV spectrum, notably in the 180–240 nm and 250–280 nm ranges [9] [10]. When light traverses the spectrometer's optical path filled with air, atmospheric oxygen absorbs a portion of the UV radiation, causing an apparent increase in the sample's absorbance that is not attributable to the analyte itself. This interference is particularly acute for analytes with characteristic absorption peaks in the deep-UV region, such as sulfate (SO₄²⁻) and sulfide (S²⁻) ions [9]. Furthermore, oxygen can participate in photochemical reactions with analytes under UV illumination, leading to the generation of radical species and unintended degradation of the sample being measured [11].

Molecular Mechanisms of Oxygen Interference

The interference of oxygen in UV spectroscopy operates through two primary mechanisms: direct absorption and photochemical reactivity.

Direct Absorption of UV Light by O₂

Molecular oxygen absorbs UV light strongly in specific spectral windows. The absorption cross-section, a measure of the probability of light absorption, reaches a maximum of approximately 7.84 × 10⁻²⁰ cm²/molecule at around 180.5 nm [10]. This absorption corresponds to electronic transitions to excited states. In high-density phases, studies have shown that this absorption can be enhanced by three orders of magnitude due to the formation of antiferromagnetic O₂ pairs, indicating that intermolecular interactions between oxygen molecules play a critical role in the intensity of this phenomenon [12].

This additional absorption by O₂ introduces a significant background signal, leading to a non-linear deviation from the Beer-Lambert law at high analyte concentrations. The low detection accuracy for high-concentration SO₄²⁻ is not only due to oxygen absorption but is also attributed to a reduction in the energy required for electronic excitation per unit group caused by interactions between SO₄²⁻ groups themselves [9].

Photochemical Reactivity

Beyond simple absorption, oxygen acts as a potent reactant under UV light. In solutions, dissolved oxygen can be involved in the formation of various reactive oxygen species (ROS). For instance, in plasma-activated water, reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (RONS) such as NO₂⁻, NO₃⁻, and H₂O₂ are formed, which have their own distinct UV absorption profiles, complicating the spectrum [13].

A clear example is found in the behavior of organic semiconductors like TCNQ (7,7,8,8-tetracyanoquinodimethane). In air-equilibrated ethanol, UV illumination efficiently generates anion radicals and by-products like DCTC⁻, evidenced by a new absorption peak near 480 nm. This reaction is shut off by removing O₂, thereby stabilizing the neutral TCNQ form [11]. This underscores that for some systems, the stability of the analyte itself is dependent on the absence of oxygen during UV analysis.

The following diagram illustrates the core mechanisms through which molecular oxygen interferes with UV spectroscopic measurements.

Comparative Analysis: Air vs. Inert Atmosphere

The most effective way to isolate and quantify the impact of oxygen interference is through comparative experiments conducted in air and inert (e.g., nitrogen) atmospheres. The following table summarizes key experimental data from such investigations.

Table 1: Comparative Spectroscopic Performance in Air vs. Nitrogen Atmosphere

| Analyte | Characteristic Wavelength Range | Key Performance Metric | Performance in Air | Performance in N₂ | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SO₄²⁻ (Sulfate) | 180–200 nm | Relative Error (RE) | 5–10% | < 5% | [9] |

| SO₄²⁻ (Sulfate) | 180–200 nm | Spiked Recovery (P) | Exceeded acceptable range at some points | Within acceptable range (90–110%) | [9] |

| S²⁻ (Sulfide) | 200–300 nm | Slope of C-A Curve | Lower slope | Increased slope | [9] |

| Ni²⁺ / Cu²⁺ | 300–500 nm / 600–900 nm | Slope of C-A Curve | No significant change | No significant change | [9] |

| Dissolved Oxygen | 190–250 nm | Regression Model R² (Ultrapure Water) | Not applicable (Directly measured) | 0.99 – 0.97 | [14] |

The data reveals a clear pattern: the beneficial effect of a nitrogen atmosphere is spectral-region dependent. Analytes like Ni²⁺ and Cu²⁺, with absorption in the visible to near-infrared regions, show no significant improvement in a N₂ atmosphere because oxygen does not absorb light in these regions [9]. In contrast, for analytes in the UV region, the improvement is substantial.

For SO₄²⁻, the use of nitrogen not only brought the relative error within the acceptable sub-5% threshold but also corrected the spiked recovery percentage to within the standard 90–110% range, which was not consistently achieved in air [9]. The increase in the slope of the Concentration-Absorbance (C-A) curve for S²⁻ under N₂ indicates a direct improvement in analytical sensitivity [9]. The success of using UV spectroscopy to model dissolved oxygen saturation itself further underscores the strong and quantifiable absorption signature of oxygen in the UV region [14].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure the reproducibility of comparative atmospheric studies, the following detailed methodologies are provided.

Protocol for Nitrogen-Purged UV Spectroscopy of SO₄²⁻

This protocol is adapted from the research that demonstrated significant improvement in sulfate detection accuracy [9].

- Apparatus: Standard UV-Vis spectrophotometer (e.g., Agilent Cary Series), sealed quartz cuvettes with gas-inlet/outlet ports, a source of high-purity (≥99.99%) nitrogen gas, gas regulator, and flexible tubing.

- Reagents: High-purity water (e.g., 18.2 MΩ·cm resistivity), sodium sulfate (Na₂SO₄) for preparation of standard solutions, and other relevant ionic solutions for matrix-matching if needed.

- Procedure:

- System Purge: Place the cuvette in the spectrophotometer and connect the inlet port to the nitrogen source. Maintain a continuous, gentle flow of N₂ through the sealed cuvette for at least 15–20 minutes prior to measurement to fully displace oxygen from the optical path and the sample chamber environment.

- Baseline Correction: Fill the cuvette with the high-purity water blank. Under continuous N₂ flow, record the baseline spectrum over the desired range (e.g., 180–220 nm for sulfate).

- Sample Measurement: Replace the blank with the analyte solution. Ensure the cuvette remains sealed and under N₂ flow. Measure the absorption spectrum of the sample.

- Data Analysis: Construct the Concentration-Absorbance (C-A) calibration curve using data acquired under the N₂ atmosphere. The linearity (R²) and slope of the curve are expected to be higher compared to an air atmosphere.

Protocol for Investigating O₂-Dependent Photoreactions

This protocol outlines the method for studying the synergistic effect of oxygen and UV light on analyte stability, as demonstrated with TCNQ derivatives [11].

- Apparatus: UV-Vis spectrophotometer, standard quartz cuvettes, a continuous-wave (CW) UV lamp (e.g., 365 nm, 4 W), and facilities for creating an air-equilibrated versus a deaerated environment (e.g., via N₂ purging).

- Reagents: Target analyte (e.g., TCNQ, F₂TCNQ), and solvents of varying polarity (e.g., Toluene, Acetonitrile, Ethanol).

- Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare identical solutions of the analyte in different solvents.

- Atmosphere Control: For a given solvent, create two conditions:

- Air-equilibrated: The solution is open to air.

- Deaerated: Sparge the solution with N₂ for 10–15 minutes in the cuvette, then seal it.

- UV Illumination & Measurement: Place the cuvette in the spectrophotometer. Acquire an initial absorption spectrum. Then, expose the cuvette to the UV lamp for controlled intervals (e.g., 0, 3, 6, 9, 12, 15 minutes), acquiring a full spectrum after each interval.

- Data Analysis: Monitor the decay of the primary analyte peaks and the emergence of new peaks corresponding to photoproducts (e.g., the peak near 480 nm for DCTC⁻). Compare the reaction kinetics and product formation between the air-equilibrated and deaerated samples.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Successful research into atmospheric effects on spectroscopy requires specific materials and reagents. The following table lists key items and their functions.

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Comparative Atmospheric Studies

| Item | Specification / Example | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Nitrogen Gas | ≥99.99% purity, with regulator | Creates an inert atmosphere by displacing O₂ from the optical path and sample environment. |

| Sealed Spectroscopic Cuvettes | Quartz (for UV), with gas inlet/outlet ports | Allows for controlled atmosphere within the sample chamber during measurement. |

| Deuterium Lamp | MILAS A410JU or equivalent | Provides stable and intense UV light source for spectrophotometer. |

| High-Purity Solvents | HPLC/Spectrophotometric grade ethanol, acetonitrile, water | Minimizes background absorption and unintended photochemical reactions from solvent impurities. |

| Standard Reference Materials | e.g., Sodium Sulfate (Na₂SO₄), TCNQ | Used for preparing calibration standards and validating method performance. |

| UV Light Source | Continuous-wave UV lamp (e.g., 365 nm) | Used in photostability studies to induce O₂-dependent photoreactions. |

Visualization of the Experimental Workflow

The complete experimental workflow for conducting a comparative investigation and validating the impact of atmosphere is summarized below.

The evidence unequivocally demonstrates that molecular oxygen is a significant interfering agent in UV spectroscopy, with its impact governed by both direct absorption and photochemical pathways. The comparative data between air and nitrogen atmospheres reveals that employing an inert atmosphere is not merely a refinement but a critical necessity for achieving accurate and reliable results when working with UV-absorbing analytes, particularly in the deep-UV region below 240 nm.

For researchers in drug development and analytical science, where precision is paramount, integrating nitrogen-purged spectroscopy for relevant assays should be considered a best practice. It mitigates a key source of error, improves detection limits, and ensures the integrity of samples susceptible to photo-oxidation. This guide provides the foundational data, experimental protocols, and technical rationale to support the adoption of this improved methodology, ultimately contributing to more robust and reproducible scientific outcomes.

Characterizing Aerosol Fluorescence Spectra in Urban vs. Rural Environments

Aerosol fluorescence spectroscopy has emerged as a powerful tool for probing the composition and sources of atmospheric particles. This technique leverages the principle that certain atmospheric aerosols, when excited by ultraviolet (UV) light, emit fluorescent radiation at longer wavelengths. The resulting spectral signatures act as unique fingerprints, providing researchers with a non-destructive method to identify particle types, such as those from biological sources, combustion processes, or mineral dust. Within the broader context of comparative spectroscopic behavior in different atmospheres, understanding the distinctions between urban and rural aerosol fluorescence is crucial. Urban environments are typically dominated by anthropogenic emissions, including black carbon from traffic and brown carbon from residential heating, whereas rural areas often exhibit stronger influences from biogenic emissions, pollen, fungal spores, and mineral dust. This guide provides an objective comparison of aerosol fluorescence properties across these distinct environments, supported by recent experimental data and detailed methodologies.

Comparative Analysis of Spectral Signatures

Spectral Characteristics and Intensive Parameters

Aerosol fluorescence spectra provide distinctive features that enable the differentiation of particle types commonly found in urban and rural settings. Key parameters for this analysis include the spectral fluorescence capacity (an intensive parameter similar to a lidar fluorescence ratio) and the wavelength of maximum fluorescence (λ_max). These metrics help normalize signals against particle concentration, allowing for direct comparison of aerosol composition across different environments and source regions [2].

Table 1: Comparative Spectral Properties of Major Aerosol Types

| Aerosol Type | Typical Environment | Fluorescence Maximum (λ_max) | Spectral Fluorescence Capacity | Spectral Shape Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biomass Burning Aerosol (BBA) | Urban & Rural (transported) | 500 - 550 nm (when excited at 355 nm) [2] | High (up to >9×10⁻⁶ nm⁻¹) [2] | Rounded shape; can become Gaussian with altitude; often shows red shift (longer wavelengths) with height [2] |

| Saharan Dust | Rural/Background (long-range transport) | < 500 nm [2] | Low (<1×10⁻⁶ nm⁻¹) [2] | Skewed to short wavelengths; linear decrease in spectral backscatter at longer wavelengths [2] |

| Primary Biological Aerosol Particles (PBAP) | Predominantly Rural/Forested | Multiple peaks (e.g., 300-400 nm, 400-600 nm) [15] | Variable (instrument-dependent) | Fluorescence across multiple channels (F1, F2, F3) depending on specific bio-fluorophores [15] |

| Urban Anthropogenic Aerosol | Urban | Not distinctly reported | Not distinctly reported | Often serves as fluorescent background against which PBAP is identified [16] |

Concentration and Size Distribution Variations

The concentration and size distribution of fluorescent aerosols exhibit significant spatial and temporal variability, driven by differences in source strength and atmospheric processing.

Table 2: Concentration and Size Characteristics Across Environments

| Location & Environment | Key Fluorescent Particle Types | Predominant Size Modes | Comparative Concentration Insights |

|---|---|---|---|

| Urban (Manchester, UK) [16] | Fluorescent background aerosol (non-biological) | Fine mode: 0.8-1.2 μm; Secondary fluorescent mode: 2-4 μm [16] | F3 channel particles outnumbered F1 by 2-3 times [16] |

| Tropical Rainforest (Borneo, Malaysia) [16] | Primary Biological Aerosol (PBA) | Non-fluorescent: 0.8-1.2 μm; Fluorescent: 3-4 μm [16] | Similar concentrations in F1 and F3 channels [16] |

| Mediterranean Background (Lecce, Italy) [15] | Winter: Soot, bacteria; Spring: Fungal spores, pollen, dust | Winter: Fine-mode; Spring: Larger particles [15] | Fluorescent intensity higher in spring, indicating more biological/organic material [15] |

| Urban (Athens, Greece) [17] | Black Carbon, Brown Carbon from residential wood burning (RWB) and traffic | Fine mode (PM₂.₅) [17] | BC and BrC absorption up to 3x higher at residential sites during festive nights [17] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Spectrometric Fluorescence Lidar

The Raman lidar for moisture sensing (RAMSES) exemplifies a high-performance spectrometric fluorescence lidar used for atmospheric aerosol characterization. Its experimental protocol involves several critical stages [2]:

- Laser Excitation: The system transmits UV light pulses at 354.7 nm from a frequency-tripled Nd:YAG laser operating at 30 Hz. Effective suppression of fundamental and second-harmonic generation light is crucial for accurate fluorescence measurements [2].

- Signal Reception: The receiver system employs two separate branches. A near-range receiver uses a Newtonian telescope connected via fiber to a polychromator and a UVA spectrometer (378-458 nm). A far-range receiver uses a Nasmyth-Cassegrain telescope directly coupled to a polychromator, featuring discrete channels and two spectrometers: a "water spectrometer" (385-410 nm) and a VIS spectrometer (440-750 nm) [2].

- Data Processing: Fluorescence spectra are obtained by merging data from the UVA and VIS spectrometers. The primary measured parameter is the spectral fluorescence backscatter coefficient (β_FL). The spectral fluorescence capacity is then calculated as an intensive parameter to facilitate aerosol typing and comparison [2].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the general process of acquiring and processing lidar-based aerosol fluorescence data:

UV-LIF Spectroscopy with WIBS

Wideband Integrated Bioaerosol Sensors (WIBS) represent a widely used class of instruments for real-time, in-situ characterization of fluorescent aerosols. The standard measurement protocol involves [15]:

- Particle Sizing and Detection: The WIBS optically sizes particles ranging from 0.5 to 30 μm using a light scattering source.

- Fluorescence Excitation and Detection: Particles are exposed to UV light pulses at specific wavelengths (typically 280 nm and 370 nm). The resulting fluorescence is detected across multiple channels:

- FLF280: Emission between 300-400 nm following 280 nm excitation (sensitive to Tryptophan).

- FBF280: Emission between 400-600 nm following 280 nm excitation.

- FBF_370: Emission between 400-600 nm following 370 nm excitation (sensitive to NADH and Riboflavin) [15].

- Particle Classification: Based on the fluorescence response across these channels, particles are categorized into seven types (A, B, C, AB, AC, BC, ABC) to aid in source identification and particle typing [15].

Offline Molecular Characterization

Offline techniques provide complementary, highly detailed chemical information but lack real-time capability. A typical protocol involves [18]:

- Sample Collection: PM₁ or PM₂.₅ samples are collected on filters over specified periods (e.g., 12-24 hours) at urban and forested sites simultaneously.

- Chemical Analysis: Filters are analyzed using High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry (HRMS) to determine molecular formulas and identify specific organic compounds. Thermo-optical methods are used to quantify Organic Carbon (OC) and Elemental Carbon (EC) concentrations [18].

- Data Interpretation: Statistical analysis of the molecular data helps identify source-specific markers (e.g., organosulfates, nitroaromatics) and quantify the influence of anthropogenic versus biogenic sources on aerosol composition [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Instrumentation and Reagents for Aerosol Fluorescence Research

| Instrument/Reagent | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Spectrometric Lidar (e.g., RAMSES) | Remote sensing of atmospheric fluorescence spectra using laser excitation [2]. | Large-scale vertical profiling of aerosol layers (e.g., biomass burning plumes, dust) from ground-based platforms [2]. |

| UV-LIF Spectrometer (e.g., WIBS) | In-situ, real-time detection and classification of single fluorescent aerosol particles [15]. | Monitoring bioaerosol concentrations and sources at field sites; studying particle fluorescence in controlled laboratory experiments [15]. |

| High-Resolution Mass Spectrometer (HRMS) | Molecular characterization of aerosol filter samples with high mass accuracy [18]. | Offline, detailed analysis of organic aerosol composition; identification of specific molecular markers for source apportionment [18]. |

| Thermo-optical Carbon Analyzer | Quantitative determination of Organic Carbon (OC) and Elemental Carbon (EC) in aerosol samples [18]. | Standard quantification of carbonaceous aerosol components; validation of optical fluorescence measurements [18]. |

| Calibration Standards (e.g., Polystyrene Latex Spheres) | Instrument calibration for particle sizing and fluorescence intensity reference [15]. | Quality assurance and intercomparison of measurements across different instruments and research groups [15]. |

The comparative analysis of aerosol fluorescence spectra in urban versus rural environments reveals systematic differences in spectral characteristics, particle types, and concentration patterns. Urban environments typically show fluorescence signatures influenced by combustion-derived aerosols, with a predominance of fine-mode particles and specific spectral profiles for biomass burning aerosol. In contrast, rural areas exhibit stronger influences from primary biological aerosol particles and mineral dust, characterized by different fluorescence wavelengths and size distributions. These distinctions highlight the value of fluorescence spectroscopy as a tool for aerosol source apportionment and environmental monitoring. The choice of experimental methodology—whether remote sensing with lidar, in-situ detection with WIBS, or offline molecular analysis—depends on the specific research objectives, required temporal resolution, and level of chemical detail needed. Future advancements in standardized calibration and multi-technique integration will further enhance our ability to characterize and quantify aerosol fluorescence across diverse atmospheric environments.

Exploring the 'Golden Window' for Deep-Tissue Imaging in Biomedical Applications

Optical imaging represents a powerful tool for biomedical research, offering high resolution and rich molecular information. However, its utility for deep-tissue applications has been historically constrained by light attenuation from absorption and scattering by biological components such as hemoglobin, water, and lipids [19] [20]. This limitation has driven the investigation of specific spectral regions, or "optical windows," where light penetration is maximized. Within the near-infrared (NIR) spectrum, research has evolved from the first optical window (NIR-I, 700-900 nm) to the second window (NIR-II, 1000-1700 nm), which offers significantly reduced scattering and autofluorescence [19] [21] [22]. The term "Golden Window" was notably identified and characterized by Professor Lingyan Shi and colleagues as a specific band within the shortwave infrared (SWIR) region that is particularly favorable for deep-tissue imaging [23]. This comparative guide explores the technical specifications, performance metrics, and experimental methodologies associated with the Golden Window, providing researchers with a framework for selecting appropriate imaging strategies based on specific application requirements.

Defining the Golden Window: Spectral and Physical Foundations

The "Golden Window" is precisely defined as the spectral band from approximately 1300 nm to 1375 nm [20]. In heavily pigmented tissues like the liver, an additional prominent window exists between 1550 nm and 1600 nm [20]. The enhanced performance within this window arises from a confluence of reduced light-tissue interactions:

- Reduced Scattering: Light scattering in tissue decreases proportionally with longer wavelengths, following a λ^-α relationship (where α is the scattering exponent). Consequently, NIR-II light (1000-1700 nm) experiences significantly less scattering than both visible and NIR-I light, leading to better preservation of ballistic photons that carry direct spatial information [19] [21].

- Minimized Absorption: The Golden Window strategically resides between major absorption peaks of water and lipids, two primary tissue chromophores [20]. This local minimum in the absorption spectrum allows photons to travel greater distances before being extinguished.

The combination of these factors results in a higher Michelson spatial contrast, a key metric for quantifying the clarity and effective resolution of images obtained at depth [20]. Experimental measurements using hyperspectral imaging and Monte-Carlo simulations have consistently confirmed that the highest spatial contrast for deep tissue imaging lies within this 1300-1375 nm band [20].

Comparative Performance of Optical Windows

The following tables summarize the key characteristics and quantitative performance data for different optical windows, highlighting the advantages of the Golden Window.

Table 1: Characteristics of Major Optical Windows for Biomedical Imaging

| Parameter | NIR-I Window | Broad NIR-II Window | The Golden Window |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spectral Range | 700 - 900 nm [21] [24] | 1000 - 1700 nm [21] [25] [22] | 1300 - 1375 nm [20] |

| Primary Probes | ICG, Cyanine Dyes [24] | Organic Semiconducting Fluorophores (OSFs), Quantum Dots, Carbon Nanotubes, Rare-Earth Dots [19] [21] [22] | Probes with absorption/emission in the 1300-1375 nm band |

| Tissue Penetration | < 1 cm [19] [21] | Up to 3-4 cm [21] [24] | Highest penetration within NIR-II; demonstrated up to 8 cm in phantoms [21] |

| Spatial Resolution | Limited by scattering [21] | Superior to NIR-I [21] | Highest reported spatial contrast in the NIR-II range [20] |

| Autofluorescence | Moderate to High [22] | Low [21] [22] | Very Low [20] |

| Key Advantage | Clinically available dyes (e.g., ICG) [24] | Deeper penetration than NIR-I | Optimal balance of penetration and contrast |

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Deep-Tissue Imaging Modalities and Techniques

| Technique/System | Key Principle | Demonstrated Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| DOLPHIN Imaging | NIR-II hyperspectral & diffuse imaging with computational decomposition | Resolved 0.1 mm probes in live mice; tracked probes through 8 cm tissue phantom | [21] |

| LiL-SIM | Two-photon excitation with line-scanning and lightsheet shutter mode | ~150 nm resolution at depths > 50 μm in scattering tissue | [26] |

| PRM-SRS | Hyperspectral penalized reference matching for stimulated Raman scattering | Distinguishes multiple molecular species simultaneously in multiplex imaging | [23] |

| DO-SRS | Deuterium oxide probing with SRS to track metabolic activity | Detected newly synthesized lipids, proteins, and DNA in aging studies | [23] |

| AuPANI Nanodiscs | Janus nanoparticles with NIR-II plasmon resonance | Achieved photoacoustic imaging at 15 mm depth | [25] |

Essential Toolkit for Golden Window Research

Leveraging the Golden Window requires a specific set of reagents, instruments, and computational tools.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Golden Window Imaging

| Item | Function/Description | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| NIR-II Fluorophores | Probes that absorb and/or emit within the Golden Window. Includes organic semiconducting fluorophores (OSFs), quantum dots, and single-walled carbon nanotubes. | High-resolution vascular imaging and tumor delineation [21] [22]. |

| Deuterium-Labeled Compounds | Metabolic precursors (e.g., D₂O) that incorporate into macromolecules, creating detectable C-D bonds via SRS microscopy. | Tracking de novo synthesis of lipids, proteins, and DNA in situ [23]. |

| InGaAs Cameras | Detectors with high quantum efficiency in the 900-1700 nm range, essential for capturing NIR-II and Golden Window signals. | Core component of the DOLPHIN and other custom NIR-II imaging systems [21] [20]. |

| Adam optimization-based Pointillism Deconvolution (A-PoD) | Computational image reconstruction algorithm that enhances spatial resolution and enables super-resolution SRS microscopy. | Non-invasive nanoscale imaging in live cells and tissues [23]. |

| Penalized Reference Matching (PRM) | Data processing method for spectral unmixing in SRS microscopy, allowing identification of multiple chemical species. | Multiplexed imaging of distinct molecular targets in complex biological samples [23]. |

Experimental Workflow for Golden Window Imaging

The diagram below outlines a generalized protocol for conducting a deep-tissue imaging experiment utilizing the Golden Window, integrating elements from probe preparation to data reconstruction.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

1. Probe Selection and Preparation:

- NIR-II Fluorophores: Select probes with absorption and/or emission peaks within the 1300-1375 nm Golden Window for optimal performance [20] [22]. For example, certain organic semiconducting fluorophores (OSFs) can be engineered for this range through molecular design strategies like intramolecular charge transfer regulation and J-aggregation [22]. Prepare stock solutions according to established protocols, ensuring proper solubility and sterility for biological applications.

- Deuterated Compounds: For metabolic imaging using SRS, use deuterium oxide (D₂O) as a tracer. Administer D₂O to living systems via drinking water or injection. Newly synthesized macromolecules will incorporate deuterium, creating a strong carbon-deuterium (C-D) bond that can be detected against the natural carbon-hydrogen (C-H) background via SRS microscopy [23].

2. Sample Preparation and Mounting:

- Tissue Phantoms: Create tissue-mimicking phantoms using intralipid (for scattering) and India ink (for absorption) to calibrate the imaging system and quantify penetration depth. The optical properties should be matched to those of typical biological tissues (e.g., μₐ ≈ 0.15-0.17 cm⁻¹ at 1100 nm) [20].

- Biological Samples: For ex vivo studies, use freshly excised tissues to minimize drying artifacts. Mount the sample on a quartz platform, as quartz has high transmission in the SWIR range. For in vivo studies, anesthetize the animal (e.g., mouse) and position it stably on the translation stage, ensuring the region of interest is accessible for trans- or epi-illumination [21].

3. System Configuration and Data Acquisition (e.g., DOLPHIN System):

- Excitation: Use a laser source tuned to a wavelength within the Golden Window (e.g., 1300-1375 nm) for optimal penetration [21] [20]. For SRS microscopy, two synchronized lasers (pump and Stokes) are required to target specific vibrational bonds.

- Detection: Employ a liquid nitrogen-cooled InGaAs camera with high sensitivity in the SWIR region. Configure the system for either trans-illumination (for maximum depth assessment) or epi-illumination (reflection geometry, more common for in vivo applications) [21] [20].

- Data Acquisition: Acquire hyperspectral image cubes by scanning across wavelengths within the NIR-II region. For the DOLPHIN system, this involves collecting both spectral information (HSI mode) and the diffuse profile of transmitted photons (HDI mode) to later correct for scattering [21].

4. Data Processing and Image Reconstruction:

- Pre-processing: Perform background subtraction and normalize signal intensities to correct for non-uniform illumination.

- Spectral Unmixing: Apply algorithms like Penalized Reference Matching (PRM-SRS) to decompose the hyperspectral data and distinguish the signal of interest from background autofluorescence and other chromophores [23].

- Image Enhancement: Use deconvolution algorithms such as Adam optimization-based Pointillism Deconvolution (A-PoD) to enhance spatial resolution and achieve super-resolution capabilities from the acquired data [23].

- 3D Reconstruction: For whole-animal or thick tissue imaging, computational models can be applied to the diffuse light profiles to reconstruct the three-dimensional location of the probe within the tissue [21].

The Golden Window (1300-1375 nm) represents a significant advancement in deep-tissue optical imaging, offering a quantifiable improvement in spatial contrast and penetration depth over broader NIR-I and NIR-II bands. Its effectiveness is not merely a function of moving to longer wavelengths but of strategically operating in a region of maximal tissue transparency. The continued development of compatible contrast agents—such as advanced OSFs and metabolic probes—coupled with sophisticated computational methods like A-PoD and PRM-SRS, is crucial for fully exploiting its potential. For researchers in drug development and physiology, the Golden Window provides a powerful tool for non-invasively visualizing cellular and metabolic processes in vivo, enabling insights into disease mechanisms and therapeutic efficacy at unprecedented depths and resolutions. Future progress will depend on the synergistic optimization of molecular probes, imaging hardware, and reconstruction software tailored to this specific, advantageous optical band.

Advanced Techniques and Real-World Applications Across Disciplines

Optical biomedical imaging has been pivotal in advancing the understanding of biological structure and function. While conventional approaches often focused on a single imaging modality, recent research demonstrates that diverse techniques provide complementary insights [27] [28]. Their combined output offers a more comprehensive understanding of molecular changes in aging processes, disease development, and fundamental cell biology [27] [28]. This comparative guide examines the integration of four powerful modalities: Stimulated Raman Scattering (SRS), Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging (FLIM), Multiphoton Fluorescence (MPF), and Second Harmonic Generation (SHG) microscopy.

The multi-modality approach is increasingly favored because it provides a broader range of measurements while mitigating the limitations associated with individual techniques [27] [28]. As discussed in the search results, MPF measures endogenous fluorescence to reflect metabolic changes, SHG images non-centrosymmetric structures such as collagen, SRS detects proteins and lipids based on their vibrational signatures, and FLIM provides additional metabolic information by quantifying fluorescence decay rates [23] [29]. Given their coherent properties and shared principle of nonlinear optical properties, these imaging modalities can be integrated into a single microscope setup utilizing ultrashort pulsed lasers, allowing for the acquisition of various biomarkers at localized regions to provide a more complete view of biological processes [27] [28].

Comparative Performance Analysis of Imaging Modalities

Technical Specifications and Performance Metrics

Table 1: Comparative analysis of integrated microscopy modalities

| Modality | Primary Contrast Mechanism | Spatial Resolution | Penetration Depth | Key Measured Parameters | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SRS | Vibrational spectroscopy of chemical bonds [27] | Subcellular [27] | Several hundred microns [27] | Lipid-to-protein ratio, metabolic activity via C-D bonds [27] [23] | Brain tumor margin delineation [27], metabolic tracking [23] |

| FLIM | Fluorescence decay kinetics [23] [29] | Subcellular [29] | ~250-500 μm [29] | NADH binding status [29], metabolic states | Distinguishing NADH from NADPH [29], metabolic imaging [23] |

| MPF | Autofluorescence of endogenous coenzymes [27] [28] | Subcellular [29] | ~250-500 μm [29] | Optical redox ratios (NADH/FAD) [27] [28] | Differentiating cancer vs. normal cells [27] [28] |

| SHG | Non-centrosymmetric structures [27] [28] | Subcellular [27] | ~250-500 μm [29] | Collagen abundance, alignment, structure [27] [28] | Oncology research (breast, ovarian, skin cancers) [27] [28] |

Quantitative Performance Data in Integrated Systems

Table 2: Representative experimental data from multimodal imaging studies

| Application Context | SRS Findings | MPF/FLIM Findings | SHG Findings | Integrated Platform Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tauopathy brain model | Revealed neuronal AMPK influence on microglial lipid droplet accumulation [23] | Detected metabolic shifts through NAD(P)H imaging [23] | Visualized structural changes in extracellular matrix [23] | Uncovered reversible tau-induced lipid metabolism disruption [23] |

| Diabetic kidney tissue | Mapped biochemical composition changes [23] | Captured cellular metabolic activity [23] | Revealed collagen restructuring in 2D/3D [23] | Showcased diagnostic potential of multimodal vibrational imaging [23] |

| Cancer research | Delineated tumor margins via lipid-to-protein ratio [27] | Distinguished cancer cells via altered redox ratios [27] [28] | Detected abnormal collagen in tumor microenvironment [27] [28] | Provided comprehensive tumor microenvironment profiling [27] |

Experimental Protocols for Multimodal Integration

System Configuration and Calibration

The integration of SRS, MPF, and SHG modalities into a single platform enables the acquisition of multifaceted information from the same localization within cells, tissues, or organs [27] [28]. A typical protocol involves:

- Laser Setup: Warm up the laser and wait approximately 15-20 minutes. Power on control units and monitors in the following sequence: Control box → Touch panel controller → AC adapter for main laser remote → AC adapter for sub laser remote [28].

- Detector Initialization: Power on the Si photodiode detector and lock-in amplifier for SRS detection [28].

- Beam Configuration: Configure the pump laser beams and Stokes beam. Set up the laser system with a pump beam tunable from 780 nm to 990 nm, 5-6 ps pulse width, and 80 MHz repetition rate. The Stokes laser beam typically has a fixed wavelength of 1,031 nm with a 6 ps pulse and 80 MHz repetition rate [28].

- Alignment Procedure: Ensure both pump and Stokes beams are at low power (at least 20 mW) to be visible on the alignment plate. Place one alignment plate in the optical path and adjust until beams are co-aligned [28].

For FLIM integration, additional components include time-correlated single photon counting (TCSPC) modules and specialized detectors capable of resolving fluorescence decay kinetics [29]. This integration allows quantification of the proportion of NADH that is free or protein-bound, providing deeper metabolic insights beyond intensity-based MPF measurements [29].

Data Acquisition and Image Co-Registration

A significant advantage of integrated platforms is instantaneous coregistration without the need for position adjustments, device switching, or post-analysis alignment [27] [28]. The protocol typically involves:

- Sequential Scanning: Acquire signals from each modality sequentially by adjusting laser wavelengths and detection filters while maintaining the same sample position.

- Simultaneous Detection: For compatible modalities like MPF and SHG, signals can be detected simultaneously using appropriately positioned dichroic mirrors and spectral filters [29].

- SRS Specifics: For SRS imaging, stimulated Raman loss is demodulated via a commercial lock-in amplifier, with all emission filters and excitation wavelengths carefully selected to avoid crosstalk [28].

- Thermal Considerations: When integrating thermal imaging with nonlinear microscopy, monitor sample temperature to prevent artifacts, particularly for live-cell applications [30].

Research Reagent Solutions for Multimodal Experiments

Table 3: Essential research reagents and materials for multimodal microscopy

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experiments | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Heavy water (D₂O) | Enables detection of newly synthesized macromolecules via carbon-deuterium bonds in SRS [27] [23] | Metabolic tracking of protein synthesis, lipogenesis [27] [23] |

| NADH/FAD | Endogenous metabolic coenzymes for MPF imaging of cellular redox state [27] [28] | Quantifying optical redox ratios for metabolic analysis [27] [28] |

| Deuterium-labeled compounds | Metabolic probes for SRS imaging of biosynthesis pathways [23] | Tracing newly synthesized lipids, proteins, DNA [23] |

| Ultrafast pulsed lasers | Excitation source for nonlinear optical processes [27] [28] | Enabling MPF, SHG, and SRS through multiphoton processes [27] [28] |

| Specific vibrational probes | Bioorthogonal labels for SRS microscopy [23] | Imaging drug delivery in cells, tissues, organoids [31] |

System Architecture and Experimental Workflow

Integrated Platform Architecture

Multimodal Experimental Workflow

Comparative Advantages and Limitations in Atmosphere Research

The integrated platform offers distinct advantages for comparative investigation of spectroscopic behavior in different atmospheric conditions:

- Minimal Sample Perturbation: Label-free imaging capabilities preserve sample integrity during prolonged observation under controlled atmospheres [27] [28].

- Simultaneous Structural and Metabolic Profiling: Combined SHG (structural) with MPF/FLIM (metabolic) enables correlation of tissue organization with functional states under varying oxygen conditions [27] [29].

- Chemical Specificity: SRS provides molecular identification through vibrational fingerprints, allowing precise mapping of metabolic adaptations to atmospheric changes [27] [23].

- Live-Cell Compatibility: The deep penetration and reduced phototoxicity enable real-time observation of cellular responses to atmospheric modifications [27] [28].

Current limitations include system complexity, high instrumentation costs, and the need for specialized expertise for operation and data interpretation. Additionally, while individual modalities offer high resolution, computational approaches like Adam optimization-based Pointillism Deconvolution (A-PoD) have been developed to further enhance spatial resolution and chemical specificity [23].

Future Directions and Clinical Translation

Emerging innovations in multimodal imaging platforms continue to enhance their capabilities for spectroscopic research. Notable advancements include:

- Super-Resolution Metabolic Imaging: Recent developments have achieved approximately 59 nm resolution multimolecular SRS metabolic imaging integrated with FLIM, MPF, and SHG [31].

- Deep-Tissue Imaging: Discovery of the "Golden Window" for optical penetration depth has enabled improved deep-tissue imaging capabilities [23].

- Computational Enhancements: Algorithms like hyperspectral penalized reference matching SRS (PRM-SRS) microscopy enable simultaneous distinction of multiple molecular species [23].

- Clinical Applications: These platforms show increasing promise for clinical diagnostics, particularly in intraoperative tumor margin assessment and monitoring therapeutic responses [27] [23].

For researchers and drug development professionals, these integrated platforms offer powerful tools for unraveling complex biological processes, identifying novel biomarkers, and advancing therapeutic research across a spectrum of diseases from neurodegeneration to cancer [23] [31].

Precision spectroscopy, which measures the interaction of light with matter to determine molecular structures and energy levels, is profoundly sensitive to its environmental conditions [32]. The atmospheric composition along the optical path can introduce significant interference, altering absorption intensities, shifting characteristic wavelengths, and ultimately compromising the accuracy of quantitative measurements. This comparative guide objectively evaluates different atmospheric control strategies for spectroscopic applications, with particular focus on eliminating oxygen interference in ultraviolet (UV) measurements, maintaining controlled cleanroom environments for pharmaceutical applications, and implementing advanced computational corrections.

The fundamental challenge stems from the fact that many target substances, including sulfate (SO₄²⁻) and sulfide (S²⁻), have characteristic absorption wavelengths within the ultraviolet region where oxygen molecules readily absorb light [9]. This phenomenon of additional light attenuation not attributable to sample absorption creates a fundamental limitation for direct spectral detection of high-concentration solutions in process industries. Research demonstrates that even standard air atmospheres introduce measurable errors that nitrogen purging can effectively mitigate [9]. Beyond gas composition, comprehensive atmospheric control extends to managing particulate contamination through cleanroom ventilation systems essential for pharmaceutical quality control [33].

Comparative Analysis of Atmospheric Control Methodologies

Performance Comparison of Atmospheric Control Techniques

Table 1: Comparative analysis of atmospheric control methodologies for precision spectroscopy

| Control Methodology | Operating Principle | Optimal Spectral Range | Quantitative Improvement | Implementation Complexity | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrogen Purging | Physical displacement of oxygen from optical path | UV region (180-240 nm) | Reduces relative error from 5-10% to <5% for SO₄²⁻ [9] | Medium | Ongoing cost of nitrogen supply; requires sealed instrumentation |

| Computational Correction (LUT) | Algorithmic compensation for aerosol interference | Visible to near-IR | 10% average reduction in relative difference vs. simplified models [34] | High | Requires sophisticated inversion algorithms and processing capability |

| High-Efficiency Ventilation (ACE) | Enhanced air mixing for particle control | Broad spectrum | Enables ISO-class cleanrooms (5-8); achieves cleanup in 15-20 min [33] | Very High | Significant energy consumption; specialized infrastructure needed |

| Geometric Method | Mathematical approximation ignoring aerosol effects | Limited visible applications | Generally overestimates VCDtrop except for NO₂ [34] | Low | Fails to account for critical aerosol interference |

Quantitative Impact of Atmospheric Control on Measurement Accuracy

Table 2: Quantitative improvement in detection accuracy with atmospheric control

| Target Analyte | Characteristic Wavelength Range | Atmosphere Condition | Relative Error (RE) | Spiked Recovery Percentage (P) | Key Observation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SO₄²⁻ | 180-200 nm (Deep UV) | Air | 5-10% | Sometimes exceeded acceptable limits [9] | Dense emission spectrum creates complexity |

| SO₄²⁻ | 180-200 nm (Deep UV) | Nitrogen | <5% | Returned to within standard limits [9] | Isolation of oxygen improves detection accuracy |

| S²⁻ | 200-300 nm (UV) | Air | Variable, higher baseline | Fluctuated beyond standard range | High molar absorption coefficient |

| S²⁻ | 200-300 nm (UV) | Nitrogen | Significant reduction | Stabilized within acceptable parameters | Nitrogen suppression of oxygen absorption |

| NO₂ | 300-500 nm (Visible) | Air/Nitrogen | Minimal difference | Consistently within standards [9] | Outside oxygen absorption range |

| Cu²⁺ | 600-900 nm (NIR) | Air/Nitrogen | Minimal difference | Consistently within standards [9] | Outside oxygen absorption range |

Experimental Protocols for Atmospheric Assessment in Spectroscopy

Protocol 1: Nitrogen Purging for UV Region Enhancement

Objective: To quantify the improvement in detection accuracy for ultraviolet-absorbing analytes when replacing air with nitrogen atmosphere.

Materials and Equipment:

- UV-visible spectrophotometer with nitrogen purging capability

- High-purity nitrogen gas supply with regulator

- Gas-impermeable sample cuvettes

- Standard solutions of target analytes (SO₄²⁻, S²⁻, etc.)

- Temperature control apparatus (±0.02°C capability) [35]

Methodology:

- Configure spectrophotometer with a fixed optical path (typically 5mm)

- For air atmosphere measurements: Record absorption spectra of standard solutions across concentration series

- For nitrogen atmosphere: Purge the optical chamber with nitrogen for 10 minutes prior to measurements

- Maintain constant temperature (±0.5°C) throughout both measurement sets

- Record absorption intensity at characteristic wavelengths for each concentration

- Construct concentration-absorption intensity (C-A) curves for both atmospheric conditions

- Calculate relative error (RE) and spiked recovery percentage (P) for back-calculated concentrations

Data Analysis:

- Compare slopes of C-A curves between atmospheric conditions

- Quantify reduction in relative error using the formula: RE(%) = |Measured - Actual|/Actual × 100%

- Evaluate spiked recovery percentage against standard limits (90-110%)

Protocol 2: MAX-DOAS Vertical Column Concentration Inversion

Objective: To compare different algorithmic approaches for retrieving trace gas vertical column concentrations (VCDtrop) under varying aerosol conditions.

Materials and Equipment:

- MAX-DOAS instrument capable of multi-angle observations (2°, 3°, 5°, 7°, 10°, 15°, 20°, 30°, 90°)

- QDOAS spectroscopy software (version 3.2 or higher)

- Reference spectra collected at zenith (90° elevation)

- Calibrated wavelength sources with 0.5 nm FWHM resolution [34]

Methodology:

- Collect clear sky spectral data across specified elevation angles

- Perform differential slant column density (DSCD) retrieval using QDOAS software

- Apply three distinct inversion algorithms to the same dataset:

- Geometric Method (Geometry): Assumes 1/sin(α) approximation for air mass factor

- Simplified Model Method (Model): Incorporates typical aerosol profiles

- Look-up Table Method (Table): Uses real-time aerosol profile retrieval

- Calculate tropospheric vertical column concentrations (VCDtrop) for each method using the fundamental relationship: VCDtrop = dSCDtrop / dAMFα,trop

- Compare results with satellite validation data where available

Data Analysis:

- Quantify relative differences between algorithmic approaches

- Assess correlation coefficients between methods

- Evaluate impact of aerosol optical thickness on divergence between methods

Figure 1: MAX-DOAS inversion algorithm workflow for atmospheric trace gas quantification, comparing three methodological approaches for vertical column concentration retrieval.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials for Atmospheric Spectroscopy

Table 3: Essential research reagents and materials for controlled atmospheric spectroscopy

| Item | Specification | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Nitrogen | 99.999% purity, with pressure regulator | Displacement of oxygen from UV optical path | Elimination of oxygen absorption interference below 240nm [9] |

| Calibration Gas Standards | Certified reference materials for target analytes | Instrument calibration and method validation | Quantifying detection limits and analytical accuracy [34] |

| UV-Transparent Cuvettes | Gas-impermeable, spectral range 180-900nm | Sample containment without atmospheric interference | Maintaining controlled atmosphere during measurement [9] |

| QDOAS Software | Version 3.2 or higher with appropriate fitting algorithms | Differential slant column density retrieval | MAX-DOAS spectral processing and trace gas quantification [34] |

| HEPA Filtration Systems | ISO 14644-1 compliant, with appropriate diffusers | Particulate control in cleanroom environments | Pharmaceutical spectroscopy with USP 797/800 compliance [33] |

| Temperature/Humidity Controllers | ±0.02°C temperature, ±0.5% RH humidity stability | Environmental parameter maintenance | Preventing spectroscopic drift in sensitive measurements [35] |

Advanced Implementation Considerations

Cleanroom Ventilation Efficiency Metrics

For pharmaceutical applications requiring strict particulate control, cleanroom ventilation systems must be designed with precise attention to air change effectiveness. Two key metrics defined in ISO 14644-16 include:

Air Change Effectiveness (ACE): This metric quantifies how efficiently supply air reaches specific locations in the room. It is calculated as:

Where Tₙ is the nominal time constant (equal to 1/N, where N is room air changes) and Aᵢ is the age of air at the measuring point [33].

Contamination Removal Effectiveness (CRE): This index measures the ventilation system's ability to remove contaminants from specific sources:

Proper selection of air diffusers is critical, with HEPA filters without diffusers creating unidirectional flow suitable for localized protection, while high-induction diffusers provide better mixing for uniform cleanliness throughout the room [33].

Aerosol Interference in Trace Gas Retrieval

Beyond laboratory spectroscopy, atmospheric researchers face significant challenges from aerosol interference when measuring trace gases in field settings. The look-up table (LUT) method for MAX-DOAS measurements demonstrates superior performance compared to geometric and simplified model approaches by incorporating real-time aerosol profiling [34].

Research shows that the relative difference in vertical column concentration (VCDtrop) retrieval between the LUT method and simplified model method is approximately 10% smaller on average, with improvements of up to 25% for specific aerosol optical thickness quantiles [34]. This highlights the critical importance of accounting for aerosol interference in atmospheric spectroscopy applications.

Figure 2: Interrelationship between atmospheric factors affecting spectroscopic measurements and corresponding control strategies for precision enhancement.

The comparative analysis presented in this guide demonstrates that optimal atmospheric control strategy depends heavily on specific spectroscopic application requirements. For UV spectroscopy involving analytes like SO₄²⁻ and S²⁻, nitrogen purging provides the most direct solution to oxygen interference, reducing relative errors from 5-10% to under 5% [9]. For trace gas monitoring in field applications, advanced algorithmic approaches like the look-up table method yield significant improvements over simpler geometric approximations, particularly in environments with variable aerosol loading [34].

Pharmaceutical applications requiring strict particulate control necessitate sophisticated cleanroom ventilation systems designed with careful attention to air change effectiveness metrics [33]. As precision requirements continue to increase across research and industrial applications, the integration of multiple control strategies—combining physical atmospheric manipulation with computational correction—will become increasingly essential for achieving accurate, reliable spectroscopic measurements.

Metabolic imaging is a class of non-invasive techniques that enable the in vivo visualization and quantification of metabolic processes, playing an indispensable role in revealing the metabolic status of cells and tissues during both physiological and pathological processes [36] [37]. For researchers and drug development professionals, the ability to track metabolic fluxes in real-time provides invaluable insights into disease mechanisms and treatment efficacy. Among the various techniques available, Deuterium Oxide (D₂O) labeling combined with Stimulated Raman Scattering (SRS) microscopy, termed DO-SRS, has emerged as a powerful platform for studying complex protein metabolism and other metabolic functions in live systems [36] [38]. This technique leverages the unique properties of deuterium, a stable, non-radioactive isotope of hydrogen, to act as a biological tracer. When incorporated into biomolecules, the carbon-deuterium (C-D) bond produces a strong vibrational signature in the cell-silent region of the Raman spectrum, allowing for specific detection against the complex background of native cellular components [36]. This review provides a comparative investigation of DO-SRS against other prominent metabolic imaging techniques, focusing on its spectroscopic behavior, experimental requirements, and applicability in biomedical research.

Comparative Analysis of Metabolic Imaging Techniques

The selection of an appropriate metabolic imaging technique depends on multiple factors, including the required sensitivity, spatial and temporal resolution, biocompatibility, and cost. The following table provides a structured comparison of DO-SRS with other established methods.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Metabolic Imaging Technologies

| Imaging Technique | Underlying Principle | Spatial Resolution | Key Applications | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DO-SRS | SRS detection of C-D bonds after metabolic incorporation of D₂O or D-AAs [36] | ~300 nm (xy), ~1000 nm (z) [36] | Protein synthesis/degradation, lipid metabolism, pulse-chase analysis [36] [38] | High spatial resolution, live-cell and in vivo compatibility, non-toxic, provides spatial information | Limited penetration depth in tissues, requires optimized deuterium labeling efficiency [36] |