Beyond Traditional Methods: How Likelihood Ratios Are Transforming Forensic Analysis and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive examination of the Likelihood Ratio (LR) framework and its growing influence in forensic science and drug development.

Beyond Traditional Methods: How Likelihood Ratios Are Transforming Forensic Analysis and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of the Likelihood Ratio (LR) framework and its growing influence in forensic science and drug development. It explores the foundational shift from traditional, often subjective, interpretation methods toward a quantitative, evidence-based LR paradigm. The scope includes methodological applications from diagnostic medicine to drug safety signal detection, discusses critical challenges in implementation and uncertainty quantification, and offers a comparative analysis of performance validation. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes how LRs provide a logically robust, transparent, and statistically sound framework for evaluating evidence and assessing risk.

The Paradigm Shift: From Subjective Judgment to Quantitative Evidence

In the evolving landscape of forensic science, the Likelihood Ratio (LR) has emerged as a powerful statistical framework for interpreting evidence, positioning itself as a modern alternative to more traditional methods. This guide provides an objective comparison between the LR approach and traditional forensic interpretation, detailing its core principles, calculation, and application for researchers and scientists.

Understanding the Likelihood Ratio

A Likelihood Ratio (LR) is a statistical measure that quantifies how strongly forensic evidence supports one proposition over another. It evaluates the probability of observing the evidence under two competing hypotheses, typically the prosecution's proposition (e.g., the evidence originated from the person of interest) and the defense's proposition (e.g., the evidence originated from someone else) [1] [2].

The core question an LR answers is: "How many times more likely is it to observe this evidence if the first hypothesis is true, compared to if the second hypothesis is true?" [3] [4]. In forensic science, this provides a transparent and logical method for conveying the weight of evidence, moving away from categorical statements and towards a more nuanced interpretation [1] [2].

The Mathematical Foundation

The LR is calculated using a fundamental formula based on conditional probabilities:

LR = Pr(E | Hp) / Pr(E | Hd)

Where:

- Pr(E | Hp): The probability of observing the evidence (E) given that the prosecution's hypothesis (Hp) is true.

- Pr(E | Hd): The probability of observing the evidence (E) given that the defense's hypothesis (Hd) is true. [1] [4]

An LR greater than 1 supports the prosecution's proposition (Hp). The higher the value, the stronger the support. Conversely, an LR less than 1 supports the defense's proposition (Hd). The closer the value is to zero, the stronger the support for Hd. An LR equal to 1 indicates that the evidence is equally likely under both hypotheses and therefore offers no support to either side [3] [4].

Likelihood Ratio vs. Traditional Forensic Interpretation

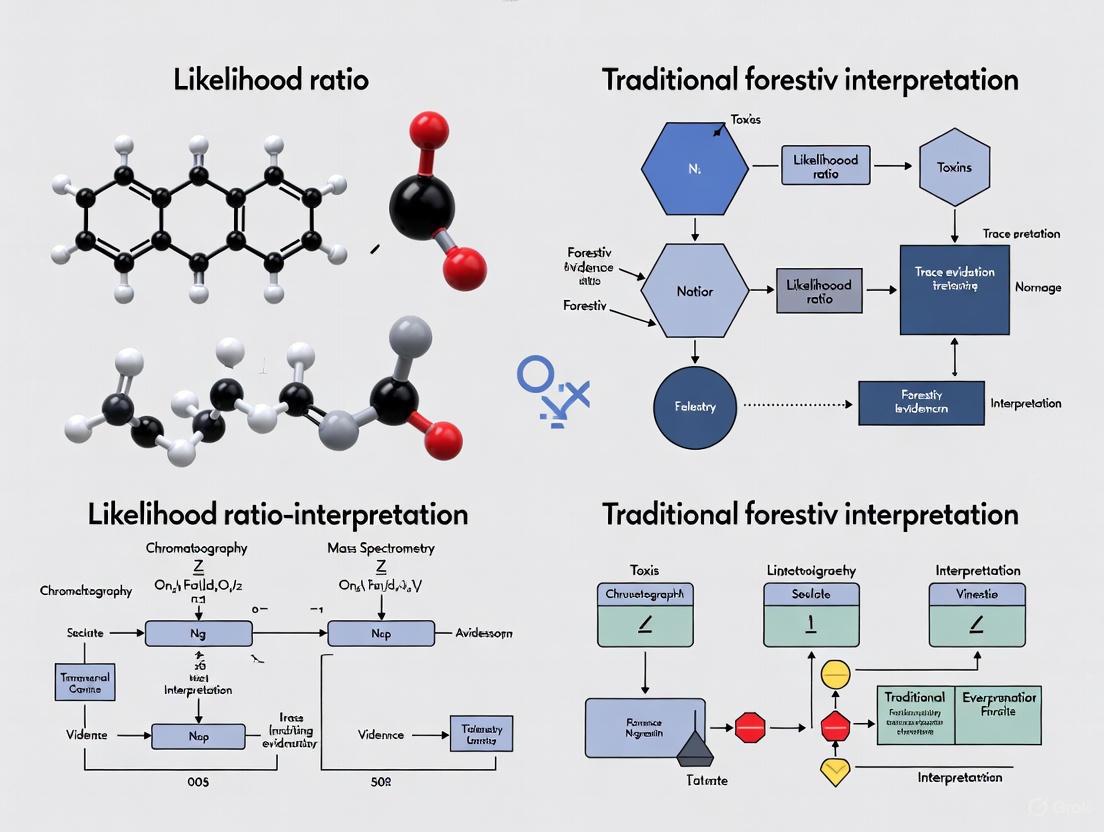

The adoption of the LR framework represents a paradigm shift from traditional forensic interpretation. The table below outlines the core differences.

| Feature | Likelihood Ratio (LR) Framework | Traditional Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Core Approach | Quantitative and statistical; expresses the weight of evidence on a continuous scale [1] [2]. | Often qualitative and categorical; may rely on definitive statements or match conclusions [2]. |

| Interpretation | Relative support for two competing propositions [1] [2]. | Often focuses on inclusion or exclusion without quantifying the strength of evidence. |

| Transparency | High; requires explicit statement of hypotheses and statistical models, making assumptions clearer [1]. | Can be lower; conclusions may be presented as subjective expert opinion. |

| Handling of Uncertainty | Inherently accounts for uncertainty through probability distributions and models [1]. | May not formally quantify uncertainty, potentially leading to overstatement of evidence [5]. |

| Role of the Expert | Provides the fact-finder with a measure of evidential strength; separates the expert's role from the fact-finder's role [1] [6]. | May encroach on the ultimate issue (e.g., stating the source is identified) [6]. |

| Foundation | Rooted in Bayesian logic and the laws of probability [1] [3]. | Rooted in practitioner experience and heuristic methods. |

Experimental Protocols for LR Calculation

Implementing the LR framework requires a structured methodology. The following workflow and detailed protocols illustrate how LRs are derived in practice, using a DNA evidence example.

Detailed Methodological Steps

1. Hypothesis Formulation The first critical step is to define two mutually exclusive and exhaustive hypotheses within the context of the case. For a DNA evidence example:

- Hp (Prosecution's Proposition): "The DNA profile originates from the Person of Interest (POI)."

- Hd (Defense's Proposition): "The DNA profile originates from an unknown individual unrelated to the POI in the population." [1] [6]

2. Data Collection & Modeling This involves gathering the data necessary to compute the probabilities in the LR formula.

- Case Evidence: The DNA profile from the crime scene evidence.

- Reference Data: The DNA profile from the Person of Interest (POI).

- Background Data: A relevant population database of DNA profiles to estimate how common or rare the observed features are, which is essential for calculating Pr(E | Hd) [5].

3. Probability Calculation using a Statistical Model This is the computational core where Pr(E|Hp) and Pr(E|Hd) are estimated. For complex evidence like DNA mixtures, probabilistic genotyping (PG) software is used.

- Pr(E | Hp): The probability of the evidence is calculated assuming the POI is a contributor. With a single-source DNA sample, this probability is typically high (close to 1).

- Pr(E | Hd): The probability of the evidence is calculated assuming the DNA came from an unknown random individual from the population. The model uses the population database to assess the typicality of the evidence profile—that is, how likely it is to appear by chance. A very common profile leads to a higher probability, while a rare profile leads to a lower probability [5] [6].

4. LR Computation and Interpretation The final LR is calculated, and its meaning is interpreted according to established scales.

- Calculation Example: If the statistical model outputs Pr(E|Hp) = 0.95 and Pr(E|Hd) = 0.0001, then LR = 0.95 / 0.0001 = 9,500.

- Interpretation: An LR of 9,500 can be verbally expressed as "The evidence provides very strong support for the prosecution's proposition (Hp) over the defense's proposition (Hd)." [3] [4]

Quantitative Data in Diagnostic Testing vs. Forensic Science

While our focus is on forensics, the LR is also a cornerstone in diagnostic medicine. The concepts are directly transferable, offering a valuable perspective. The table below summarizes how LRs are used to evaluate medical tests, based on their sensitivity and specificity.

Table: Likelihood Ratios in Diagnostic Test Interpretation [7] [3] [4]

| Positive LR (LR+) | Negative LR (LR-) | Interpretation of Diagnostic Test Strength | Approximate Change in Post-Test Probability* |

|---|---|---|---|

| > 10 | < 0.1 | Large / Conclusive shift in likelihood | +45% (LR+) / -45% (LR-) |

| 5 - 10 | 0.1 - 0.2 | Moderate shift in likelihood | +30% to +45% (LR+) / -30% to -45% (LR-) |

| 2 - 5 | 0.2 - 0.5 | Slight but sometimes important shift | +15% to +30% (LR+) / -15% to -30% (LR-) |

| 1 - 2 | 0.5 - 1 | Minimal shift; rarely important | 0% to +15% (LR+) / 0% to -15% (LR-) |

Note: Applied when pre-test probability is between 30% and 70%.

Formulas:

- Positive Likelihood Ratio (LR+) = Sensitivity / (1 - Specificity) [7] [3] [4]

- Negative Likelihood Ratio (LR-) = (1 - Sensitivity) / Specificity [7] [3] [4]

Calculation Example: Consider a test with 90% sensitivity and 85% specificity:

- LR+ = 0.90 / (1 - 0.85) = 0.90 / 0.15 = 6. This means a positive test result is 6 times more likely in a patient with the disease than in one without it [3].

- LR- = (1 - 0.90) / 0.85 = 0.10 / 0.85 ≈ 0.12. This means a negative test result is about 0.12 times as likely (or about 1/8th as likely) in a patient with the disease [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Components for LR Implementation

Successfully applying the LR framework in research or casework relies on several key components. The table below details these essential "research reagents" and their functions.

| Tool / Component | Function in LR Calculation |

|---|---|

| Relevant Population Database | Provides background data to estimate the rarity of observed features (e.g., DNA alleles, fingerprint patterns) and calculate Pr(E|Hd) [5]. |

| Statistical Model / Software | The computational engine (e.g., probabilistic genotyping software for DNA) that calculates the probabilities of the evidence under both Hp and Hd [6]. |

| Explicit Propositions | Clearly defined, mutually exclusive hypotheses (Hp and Hd) that frame the question the LR will address. This is the foundational logic of the analysis [1] [6]. |

| Uncertainty Assessment Framework | Methods (e.g., sensitivity analysis, the "uncertainty pyramid") to evaluate how different modeling choices affect the final LR, ensuring robustness and transparency [1] [8]. |

| Validated Experimental Protocols | Standardized procedures for evidence analysis to ensure that the data fed into the statistical model is reliable, reproducible, and forensically sound [2]. |

| NSC799462 | NSC799462, CAS:305834-79-1, MF:C17H17ClN2O5, MW:364.8 g/mol |

| SI-2 | SI-2, CAS:223788-33-8, MF:C15H15N5, MW:265.31 g/mol |

In conclusion, the Likelihood Ratio framework offers a scientifically rigorous, transparent, and logically sound method for interpreting forensic evidence. By directly comparing it to traditional approaches and detailing its calculation and requirements, this guide provides researchers and professionals with a clear understanding of its core principles and practical implementation.

Forensic science has long relied on traditional methods involving subjective similarity measures for evidence interpretation. Techniques such as fingerprint analysis, bite mark comparison, and handwriting examination fundamentally depend on an examiner's visual assessment and experiential judgment to determine a "match" [9] [10]. This article examines the critical limitations of these approaches, contrasting them with emerging quantitative frameworks, particularly the likelihood ratio paradigm, which offers a more statistically rigorous alternative for forensic decision-making [11] [1]. Within the broader thesis of likelihood ratio versus traditional forensic interpretation research, we explore how subjective similarity assessments introduce cognitive biases, vary between examiners, and ultimately threaten the scientific validity of forensic conclusions [12] [13]. This analysis is particularly relevant for researchers and professionals seeking to implement more objective, transparent, and statistically sound practices in forensic investigations and beyond.

Core Limitations of Traditional Similarity Measures

Traditional forensic methods employing subjective similarity measures face several fundamental challenges that undermine their reliability and scientific validity.

Dependence on Subjective Human Interpretation

The core limitation of traditional forensic methods lies in their inherent subjectivity. Unlike quantitative scientific measurements, techniques such as fingerprint analysis, handwriting examination, and bite mark comparison rely heavily on the individual examiner's expertise, experience, and judgment [9] [10]. This interpretative process is inherently personal, with conclusions varying significantly between different examiners presented with the same evidence [10]. The myth of pure scientific objectivity persists in forensic science despite clear evidence that examiners cannot completely separate their analyses from their backgrounds, experiences, and beliefs [12]. Forensic science data are inherently "theory-laden," meaning that an examiner's theoretical framework, training, and prior case exposure inevitably shape how they perceive and interpret evidence [12].

Vulnerability to Cognitive Biases

Human reasoning in forensic science is profoundly susceptible to systematic cognitive biases that can distort evidence interpretation. Forensic analysts automatically integrate information from multiple sources—both from the evidence itself (bottom-up processing) and from their pre-existing knowledge and expectations (top-down processing) [13]. This natural cognitive function, while often useful, becomes problematic in forensic contexts where independent evaluation is crucial.

Key biasing influences include [12]:

- Confirmation Bias: The tendency to seek, interpret, and recall information that confirms pre-existing expectations or case theories [10].

- Contextual Bias: Being influenced by extraneous case information, such as knowing a suspect has confessed or that other evidence strongly points to guilt.

- Base-Rate Bias: Expectations formed through past experiences, such as associating certain crime scene characteristics with particular offender profiles.

These biasing effects are heightened when evidence quality is poor—when samples are fragmented, degraded, or ambiguous—making subjective interpretation even more variable [12].

Lack of Empirical Foundations and Standardization

Many traditional forensic disciplines have developed and been used in casework without robust empirical validation of their fundamental assumptions and reliability [10]. The lack of scientific validity has plagued numerous forensic methods, with techniques like comparative bullet lead analysis and certain arson investigation methods being discredited after years of use [10]. This problem is compounded by insufficient standards and oversight across forensic laboratories, where varying levels of accreditation, training, and quality control contribute to inconsistent results and conclusions [10]. Without standardized protocols and empirical measures of reliability, it is difficult to establish uniform best practices or assess the true evidentiary value of forensic findings.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Traditional Forensic Method Limitations

| Forensic Discipline | Type of Similarity Measure | Primary Subjectivity Concerns | Documented Error Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fingerprint Analysis [9] [10] | Visual pattern matching (minutiae) | Contextual bias; confirmation bias; inter-examiner variation | Cognitive studies show contextual information can alter conclusions [12] |

| Handwriting Analysis [9] [10] | Comparison of letter forms, slant, pressure | High subjectivity; heavy reliance on examiner experience | Experts often differ in conclusions on same evidence [10] |

| Bite Mark Analysis [10] | Physical pattern matching to dentition | Lack of scientific validation; high risk of misidentification | Significant potential for erroneous results [10] |

| Bloodstain Pattern Analysis [9] | Interpretation of size, shape, distribution | Experience-based conclusions; subjective interpretation | Depends heavily on individual investigator experience [9] |

| Ballistics/Firearms [9] | Visual comparison of striations | Subjective visual assessment; potential for bias | Manual comparison introduces subjectivity [9] |

Experimental Evidence Demonstrating Methodological Flaws

Rigorous experimental studies have systematically documented the limitations of traditional similarity-based forensic methods, providing crucial empirical evidence of their vulnerabilities.

Cognitive Bias Experiments in Pattern Matching

A substantial body of experimental research has demonstrated how cognitive biases influence forensic examiners' judgments, particularly in pattern-matching disciplines like fingerprint analysis.

Experimental Protocol: Typical studies in this area present the same physical evidence to different groups of examiners under varying conditions [12] [13]. One group receives the evidence with no contextual information, while another receives biasing information, such as knowing the suspect has confessed or that other evidence strongly indicates guilt. The examiners are then asked to determine whether the evidence matches a known sample.

Key Findings: Multiple studies have revealed that forensic examiners' conclusions can be significantly influenced by contextual information. For example, fingerprint analysts who received biasing contextual information were more likely to declare a match between prints than those who did not receive such information, even when examining the same evidence [12]. This effect demonstrates the cognitive impenetrability of certain perceptual processes—even when examiners are aware of potential bias, they cannot always "unsee" their initial interpretations once contextual information has influenced their perception [13].

Inter-Laboratory and Intra-Examiner Reliability Studies

Experiments assessing the consistency of forensic conclusions across different laboratories and examiners have revealed alarming variations in results and interpretations.

Experimental Protocol: These studies typically involve sending the same evidence samples to multiple forensic laboratories or multiple examiners within the same laboratory. The researchers then analyze the degree of consensus in the results and conclusions returned.

Key Findings: Research has demonstrated that differing conclusions occur regularly, particularly with challenging evidence samples [10]. This inconsistency stems from several factors, including:

- Varying Methodologies: Different examiners may employ different comparison techniques or weight features differently based on their training and experiences [12].

- Laboratory Protocols: Laboratories operate with different standards, accreditation levels, and quality control measures, contributing to inconsistent results [10].

- Evidence Quality: With fragmented, degraded, or ambiguous evidence, subjective interpretation becomes increasingly variable [12].

These findings challenge the foundational premise of reliability in traditional forensic methods and highlight the need for more standardized, quantitative approaches.

Diagram 1: Cognitive Bias in Traditional Forensic Analysis

The Likelihood Ratio Framework: A Quantitative Alternative

The likelihood ratio (LR) framework represents a fundamentally different approach to forensic evidence evaluation that addresses many limitations of traditional similarity measures.

Conceptual Foundation and Implementation

The likelihood ratio provides a statistical measure of evidentiary strength by comparing the probability of the evidence under two competing hypotheses [11] [1]. The formula is expressed as:

LR = Pr(E|Hp) / Pr(E|Hd)

Where E represents the observed evidence, Hp is the prosecution's hypothesis (typically that the suspect is the source), and Hd is the defense hypothesis (typically that someone else is the source) [11]. This approach forces explicit consideration of alternative explanations and prevents the false dichotomy of "match" or "non-match" that characterizes traditional methods [11].

Core Principles: Proper implementation of the LR framework requires adherence to three fundamental principles [11]:

- Always consider at least one alternative hypothesis, preventing single-hypothesis testing.

- Always consider the probability of the evidence given the proposition, not the probability of the proposition given the evidence (avoiding the prosecutor's fallacy).

- Always consider the framework of circumstance, ensuring evidence is evaluated in case context.

Advantages Over Traditional Similarity Measures

The LR framework offers several significant advantages that address the specific limitations of traditional methods:

- Transparency and Reproducibility: The LR makes reasoning explicit and quantifiable, allowing other experts to review, challenge, and replicate the analysis [1].

- Explicit Uncertainty Characterization: Unlike categorical statements of identification, the LR explicitly communicates the strength of evidence, not its ultimate probative value [1].

- Reduced Cognitive Bias: By requiring simultaneous evaluation of competing hypotheses, the LR framework mitigates confirmation bias and contextual influences [11].

Table 2: Likelihood Ratio vs. Traditional Similarity Assessment

| Evaluation Aspect | Traditional Similarity Measures | Likelihood Ratio Framework |

|---|---|---|

| Foundation | Experiential, subjective judgment [9] [10] | Statistical, quantitative reasoning [11] [1] |

| Output | Categorical (match/no match/inconclusive) [9] | Continuous measure of evidentiary strength [11] |

| Uncertainty Handling | Often unstated or implicit [10] | Explicitly quantified and communicated [1] |

| Bias Mitigation | Vulnerable to cognitive biases [12] [13] | Structured to minimize contextual influences [11] |

| Transparency | Opaque decision process [10] | Explicit, documented reasoning chain [1] |

| Scientific Foundation | Variable, often lacking empirical validation [10] | Based on probability theory and statistics [11] [1] |

Research Toolkit: Essential Methodological Components

Implementing rigorous forensic evaluation methods requires specific analytical tools and approaches. The following research toolkit details essential components for robust evidence analysis.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Forensic Evaluation

| Tool/Technique | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Likelihood Ratio Framework [11] [1] | Quantifies evidentiary strength by comparing probability of evidence under competing hypotheses | Statistical evaluation of forensic evidence; DNA interpretation; pattern evidence |

| Cognitive Bias Testing [12] [13] | Identifies and measures contextual influences on decision-making | Experimental validation of forensic methods; proficiency testing; procedure development |

| "Black-Box" Studies [1] | Evaluates method performance using control cases with known ground truth | Empirical measurement of error rates; validation of forensic disciplines |

| Assumptions Lattice & Uncertainty Pyramid [1] | Structures evaluation of how assumptions affect conclusions | Uncertainty analysis in statistical evaluations; sensitivity analysis |

| Bayesian Statistical Software | Computes complex probability calculations | Implementation of likelihood ratios; statistical modeling of evidence |

| N-((1-(N-(2-((2-((2-Amino-1-hydroxy-4-(methylsulfanyl)butylidene)amino)-4-carboxy-1-hydroxybutylidene)amino)-1-hydroxy-3-(1H-imidazol-5-yl)propylidene)phenylalanyl)pyrrolidin-2-yl)(hydroxy)methylidene)glycylproline | Semax Peptide for Research|RUO|High-Purity | |

| ATN-161 | ATN-161, CAS:33016-12-5, MF:C19H18N2O2, MW:306.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Diagram 2: Likelihood Ratio Evaluation Workflow

Traditional forensic methods relying on subjective similarity measures face fundamental limitations that threaten the validity and reliability of their conclusions. The dependence on human interpretation, vulnerability to cognitive biases, and lack of empirical foundations present significant challenges for both research and practice [9] [12] [10]. The likelihood ratio framework offers a promising alternative, providing statistical rigor, transparency, and explicit uncertainty characterization [11] [1]. For researchers and forensic professionals, embracing this quantitative paradigm represents a crucial step toward evidence-based practice. Future progress requires continued development of validated statistical methods, implementation of bias mitigation procedures, and rigorous empirical testing of all forensic evaluation techniques [1] [13]. This evolution from subjective judgment to quantitative reasoning is essential for forensic science to meet scientific standards and fulfill its role in the justice system.

The interpretation of forensic evidence has undergone a fundamental paradigm shift, moving from subjective expert opinion to a structured, logical framework based on probability theory. This transition centers on the adoption of the Bayesian framework and the use of the likelihood ratio (LR) as a standardized approach for evaluating and communicating the strength of forensic evidence [11] [14]. Where traditional methods often relied on categorical statements or implicit reasoning, the Bayesian framework provides a transparent, quantitative structure for weighing evidence under competing propositions, typically the prosecution's hypothesis (H1) and the defense hypothesis (H2) [15] [16].

This shift addresses growing concerns about forensic science reliability, highlighted by studies of wrongful convictions where false or misleading forensic evidence was a contributing factor in numerous cases [17]. The Bayesian framework establishes a logical foundation that forces explicit consideration of uncertainties and alternative explanations, thereby minimizing cognitive biases and improving the scientific rigor of forensic testimony [11].

Core Principles: Likelihood Ratio vs. Traditional Methods

The Likelihood Ratio Framework

The likelihood ratio represents the core of the Bayesian approach to forensic evidence interpretation. Formally, it is defined as the ratio of two probabilities under competing hypotheses [15]:

LR = P(E|H1) / P(E|H2)

Where:

- P(E|H1) is the probability of observing the evidence (E) if the prosecution's hypothesis (H1) is true

- P(E|H2) is the probability of observing the evidence (E) if the defense hypothesis (H2) is true [15]

The resulting value indicates the direction and strength of the evidence [15]:

- LR > 1: Evidence supports H1 over H2

- LR = 1: Evidence equally supports both hypotheses (neutral)

- LR < 1: Evidence supports H2 over H1

The forensic science community has developed verbal equivalents to help communicate the meaning of different LR ranges, though these are intended as guides rather than strict classifications [15]:

Table 1: Likelihood Ratio Verbal Equivalents

| Likelihood Ratio Range | Verbal Equivalent |

|---|---|

| 1-10 | Limited evidence to support |

| 10-100 | Moderate evidence to support |

| 100-1000 | Moderately strong evidence to support |

| 1000-10000 | Strong evidence to support |

| >10000 | Very strong evidence to support |

Traditional Forensic Interpretation Methods

Traditional forensic methods have varied by discipline but share common characteristics that differentiate them from the Bayesian approach [9] [17]:

- Categorical conclusions: Many traditional methods resulted in definitive statements about source attribution without quantitative expression of uncertainty [17].

- Implicit reasoning: The logical pathway from evidence to conclusion was often not transparently documented [14].

- Subjectivity: Techniques such as hair comparison, bitemark analysis, and fingerprint examination relied heavily on examiner experience and judgment, introducing potential for cognitive bias [9] [17].

- Non-numeric reporting: Conclusions were typically expressed verbally (e.g., "consistent with," "could have originated from") without quantitative measures of evidentiary strength [17].

Comparative Analysis: Quantitative Framework vs. Traditional Practice

Philosophical and Methodological Differences

The Bayesian framework and traditional methods differ fundamentally in their philosophical approaches to evidence interpretation:

Table 2: Framework Comparison: Bayesian vs. Traditional Methods

| Aspect | Bayesian Framework | Traditional Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Foundation | Probability theory and logical reasoning | Expert experience and precedent |

| Uncertainty Handling | Explicitly quantified through probabilities | Often implicit or unquantified |

| Transparency | High - reasoning pathway is documented | Variable - dependent on examiner documentation |

| Standardization | Consistent mathematical structure | Discipline-specific practices |

| Bias Mitigation | Built-in through alternative hypothesis requirement | Relies on examiner training and protocols |

| Communication | Quantitative (LR) with optional verbal equivalents | Primarily verbal conclusions |

Performance in Wrongful Conviction Analyses

Research on wrongful convictions reveals stark differences in error rates between methodologies. A comprehensive analysis of 732 exoneration cases identified 1,391 forensic examinations where errors contributed to miscarriages of justice [17]. The distribution of errors across forensic disciplines shows particular patterns:

Table 3: Forensic Discipline Error Rates in Wrongful Convictions

| Discipline | Percentage of Examinations Containing Case Error | Percentage with Individualization/Classification Errors |

|---|---|---|

| Seized drug analysis | 100% | 100% |

| Bitemark | 77% | 73% |

| Shoe/foot impression | 66% | 41% |

| Fire debris investigation | 78% | 38% |

| Forensic medicine (pediatric sexual abuse) | 72% | 34% |

| Serology | 68% | 26% |

| Firearms identification | 39% | 26% |

| Hair comparison | 59% | 20% |

| Latent fingerprint | 46% | 18% |

| DNA | 64% | 14% |

| Forensic pathology | 46% | 13% |

The data reveals that disciplines slower to adopt Bayesian methods and quantitative approaches generally demonstrated higher rates of individualization and classification errors [17].

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Case Assessment and Interpretation (CAI) Framework

The Case Assessment and Interpretation (CAI) framework represents a practical implementation of Bayesian principles in forensic casework [14]. This methodology provides a structured approach for applying likelihood ratios throughout the investigative process:

- Case Formulation: Define competing propositions (prosecution and defense hypotheses) based on the framework of circumstances [11].

- Evidence Evaluation: Assess which items of evidence can potentially distinguish between the competing propositions.

- Likelihood Ratio Calculation: Compute LRs for each relevant piece of evidence using appropriate statistical models.

- Case Synthesis: Combine LRs (where independent) to assess the combined strength of evidence.

- Communication: Present findings with clear explanation of limitations and uncertainties.

The CAI framework emphasizes three fundamental principles for proper forensic interpretation [11]:

- Principle #1: Always consider at least one alternative hypothesis

- Principle #2: Always consider the probability of the evidence given the proposition, not the probability of the proposition given the evidence

- Principle #3: Always consider the framework of circumstance

DNA Interpretation Protocols

DNA analysis represents the most standardized implementation of Bayesian methods in forensic science. The ANSI/ASB Standard 040 provides requirements for laboratory DNA interpretation and comparison protocols [18]. The standard encompasses:

- Probabilistic genotyping: Using statistical models to compute LRs for complex DNA mixtures

- Validation requirements: Establishing scientific validity and reliability of interpretation methods

- Uncertainty characterization: Accounting for biological and technical variations in evidence

The Bayesian framework for DNA evidence interpretation follows this logical pathway, which can be visualized as:

Postmortem Interval Estimation Protocol

The application of Bayesian methods to postmortem interval (PMI) estimation demonstrates how this framework handles highly uncertain temporal evidence [16]. The experimental protocol involves:

- Training Data Collection: Compile decomposition data from known PMI cases with body scoring under standardized taphonomic conditions.

- Multivariate Model Development: Create statistical models linking decomposition metrics to time since death using the expectation-maximization (EM) algorithm.

- Likelihood Function Calculation: Compute probability of observed decomposition state given different hypothetical PMIs.

- LR Computation: Evaluate competing PMI hypotheses using likelihood ratios based on the multivariate model.

- Uncertainty Communication: Present results with clear characterization of precision limitations and underlying assumptions.

This approach acknowledges that PMI estimates come with significant uncertainty—a PMI might reasonably be twice or half the point estimate—and provides a structured way to communicate this uncertainty to investigators and courts [16].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Methodological Components

Successful implementation of the Bayesian framework requires specific methodological components and statistical tools:

Table 4: Essential Research Components for Bayesian Forensic Implementation

| Component | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Probabilistic Genotyping Software | Computes LRs for complex DNA mixtures | STRmix, TrueAllele |

| Statistical Modeling Platforms | Develops predictive models for evidence interpretation | R, Python with Bayesian libraries |

| Validation Databases | Provides population data for probability calculations | Population-specific allele frequency databases |

| Uncertainty Quantification Tools | Characterizes range of possible LR values | Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods |

| Decision Framework Guides | Translates LRs into verbal equivalents for communication | ENFSI Guideline Scale, SWGDAM Interpretation Guidelines |

| Atpenin A5 | TPEN|Zinc Chelator|For Research Use Only | |

| TPI-1 | TPI-1, CAS:79756-69-7, MF:C12H6Cl2O2, MW:253.08 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Uncertainty Characterization: The Assumptions Lattice

A critical advancement in modern Bayesian forensic science is the formal characterization of uncertainty through an assumptions lattice and uncertainty pyramid [1]. This approach acknowledges that likelihood ratios depend on modeling choices and data limitations that must be transparently communicated.

The assumptions lattice explores the range of LR values attainable by models satisfying different reasonableness criteria, allowing forensic researchers to understand how interpretation varies with different assumptions [1]. This represents a significant improvement over traditional methods where uncertainty was often unquantified or subjectively assessed.

The relationship between evidence, hypotheses, and conclusions in the Bayesian framework can be visualized as a structured decision pathway:

The Bayesian framework represents a fundamental advancement in forensic science, providing a logical foundation for evidence interpretation that is transparent, measurable, and scientifically rigorous. The likelihood ratio approach offers distinct advantages over traditional methods through its explicit quantification of evidentiary strength, mandatory consideration of alternative hypotheses, and structured uncertainty characterization.

While implementation challenges remain—particularly regarding cognitive bias mitigation, computational complexity, and interdisciplinary communication—the Bayesian framework establishes a standardized methodology for evaluating forensic evidence that aligns with scientific principles and legal standards of proof [11] [1]. As forensic science continues to evolve, this logical foundation provides the necessary structure for developing more robust, reliable, and valid forensic practices across disciplines.

The transition from traditional methods to the Bayesian framework reflects a maturation of forensic science as a discipline, moving from experience-based conclusions to mathematically structured reasoning that properly accounts for the inherent uncertainties in forensic evidence evaluation.

The interpretation of forensic evidence is undergoing a fundamental paradigm shift, moving from traditional categorical conclusions towards a more rigorous statistical framework based on the Likelihood Ratio (LR). This shift is central to modernizing forensic practice, as highlighted by key research agendas like the National Institute of Justice's Forensic Science Strategic Research Plan, which prioritizes the "evaluation of the use of methods to express the weight of evidence (e.g., likelihood ratios, verbal scales)" [19]. The LR provides a logically coherent method for updating beliefs about competing propositions based on scientific evidence. Unlike traditional approaches that might offer an "identification" or "exclusion" without explicit statistical foundation, the LR quantitatively compares the probability of the evidence under two opposing hypotheses—typically, the same-source proposition (the evidence came from the known source) and the different-source proposition (the evidence came from a random source from a relevant population).

This guide objectively compares the performance of the LR framework against traditional forensic interpretation methods. We focus on its core advantages—transparency, robustness, and logical coherence—by examining experimental data and protocols from recent research across diverse forensic disciplines, including digital forensics, firearms and toolmarks, kinship analysis, and handwriting comparison. The analysis demonstrates that while the LR framework presents implementation challenges, its methodological strengths offer a path toward more standardized, reliable, and interpretable forensic science.

Experimental Comparisons: LR vs. Traditional Methods

The table below summarizes key experimental findings from recent studies that compare LR-based methods with traditional forensic approaches.

Table 1: Experimental Performance Comparison of LR Methods vs. Traditional Approaches

| Forensic Discipline | LR Method / Model | Traditional Method | Key Performance Metric | Result / Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digital Forensics (Categorical Count Data) [20] | Closed-form LR model for user-generated event data | Non-probabilistic source assessment | Theoretical analysis & real-world dataset evaluation | LR provides a quantifiable measure of evidence strength for event data, a domain with few statistical methods. |

| Kinship Analysis (SNP Data) [21] | KinSNP-LR (Dynamic SNP selection) | Identity by State (IBS) / Identity by Descent (IBD) segment methods | Accuracy in resolving second-degree relationships | 96.8% accuracy with a weighted F1 score of 0.975 across 2,244 tested pairs. |

| Firearms & Toolmarks (Categorical Conclusions) [22] | LR conversion of AFTE conclusions (e.g., "Identification", "Inconclusive") | Subjective categorical reporting (AFTE scale) | Calibration and meaningful weight of evidence | Direct LR calculation provides a transparent and continuous scale, overcoming the subjective and opaque nature of traditional conclusions. |

| Handwriting & Glass Analysis (Specific Source) [23] | Machine Learning Score-based LR with resampling | Non-probabilistic comparison | System performance with limited data | The proposed LR method outperforms current alternatives and approaches ideal-scenario performance. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and critical evaluation, this section details the methodologies from two key experiments cited in the performance overview.

Protocol 1: KinSNP-LR for Kinship Inference

This protocol validates a Likelihood Ratio approach for inferring close kinship from dynamically selected SNPs, aligning with traditional forensic standards [21].

- Objective: To enable forensic laboratories to integrate whole genome sequencing (WGS) data into existing accredited relationship testing frameworks using an LR-based methodology for comparisons up to second-degree relatives.

- Data Curation:

- A preselected panel of 222,366 SNPs from the gnomAD v4 database was used as the foundation.

- Empirical validation was performed using the 1,000 Genomes Project data (3,202 samples), including 1,200 parent-child, 12 full-sibling, and 32 second-degree pairs.

- Supplementary simulations were conducted using Ped-sim software with unrelated founders from diverse populations to generate families with known relationships.

- Dynamic SNP Selection:

- Unlike fixed panels, SNPs are selected dynamically per case.

- The first SNP on a chromosome end that meets a configurable Minor Allele Frequency (MAF) threshold (e.g., >0.4) is selected.

- Subsequent SNPs are selected at a specified minimum genetic distance (e.g., 30-50 centimorgans) and must also meet the MAF criterion, ensuring a panel of high-information, nominally linked SNPs.

- LR Calculation:

- The likelihood of the genetic data is calculated for specific relationships (e.g., parent-child, full-siblings) versus unrelated.

- Methods follow established work[cite] by Thompson (1975), Ge et al. (2010), and Ge et al. (2011).

- Assuming independence, the cumulative LR is the product of the LRs for each individual SNP in the dynamically selected panel.

This protocol involves converting examiners' subjective categorical conclusions into Likelihood Ratios, serving as a stepping stone to full quantitative adoption [22].

- Objective: To convert categorical conclusions (e.g., from the AFTE scale: "Identification," "Inconclusive," "Elimination") into a likelihood ratio that expresses the strength of the evidence more transparently.

- Data Collection ("Black-box Studies"):

- Examiners are presented with test trials, each containing a questioned item and one or more known-source items.

- For each trial, examiners provide a categorical conclusion from an ordinal scale.

- Model Training (Pooled Data Approach):

- Response data (conclusions) are pooled across many examiners and test trials.

- A statistical model (e.g., using Dirichlet priors or an ordered probit model) is trained on this data.

- The model calculates probabilities like P("Identification" | Same Source) and P("Identification" | Different Source).

- The LR for a conclusion is the ratio of these probabilities (e.g., LR = P("ID" | Hâ‚) / P("ID" | Hâ‚‚)).

- Critical Analysis & Proposed Refinement (Bayesian Updating):

- A key critique is that a model trained on pooled data may not represent the performance of a specific examiner.

- Morrison (2017) proposed a Bayesian solution: using pooled data to create informed priors, which are then updated with the specific examiner's own proficiency test data over time.

- This refines the LR to be more representative of the individual examiner's performance.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for LR Implementation

| Item / Solution | Function / Relevance in LR Research |

|---|---|

| Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) Data | Provides the comprehensive genomic data required for dynamic SNP selection and robust kinship LR calculations [21]. |

| Reference SNP Databases (e.g., gnomAD) | Provides population-specific allele frequencies, which are critical for accurately calculating the probability of the evidence under the different-source proposition [21]. |

| Validated Likelihood Ratio Software (e.g., KinSNP-LR) | Implements the statistical models and algorithms for LR computation, ensuring reliability and reproducibility in casework [21]. |

| Proficiency Test Datasets | Curated sets of known-source and questioned-source samples used to validate LR systems and estimate error rates [22]. |

| Machine Learning Libraries (e.g., for Python/R) | Enable the development of score-based LR systems for complex pattern evidence (e.g., handwriting, glass) where defining a direct probabilistic model is difficult [23]. |

| "Black-box" Study Data | Collections of examiner conclusions from controlled trials, essential for building and validating models that convert categorical conclusions into LRs [22]. |

| (E)-UK122 TFA | (E)-UK122 TFA, CAS:940290-58-4, MF:C17H13N3O2, MW:291.30 g/mol |

| TG-003 | TG-003, CAS:719277-26-6, MF:C13H15NO2S, MW:249.33 g/mol |

Visualizing Workflows and Logical Relationships

LR Logical Framework: From Evidence to Interpretation

The following diagram illustrates the core logical pathway of the Likelihood Ratio framework, showing how raw evidence is processed to produce an interpretable measure of support.

Diagram 1: The LR Logical Pathway

Dynamic SNP Selection for Kinship Analysis

This diagram outlines the specific workflow for the KinSNP-LR method, showcasing the dynamic process of selecting informative genetic markers.

Diagram 2: KinSNP-LR Workflow

Discussion: Synthesis of Advantages and Limitations

The experimental data and protocols confirm the key advantages of the LR framework while also revealing areas for ongoing development.

Transparency: The LR framework's mathematical structure forces the explicit consideration of the probability of the evidence under both competing propositions. This contrasts with traditional methods where the path from observation to conclusion can be opaque. As [6] notes, "The Bayesian paradigm clearly separates the role of the scientist from that of the decision makers," enhancing methodological transparency.

Robustness: The performance of the KinSNP-LR method, achieving 96.8% accuracy in kinship analysis [21], demonstrates the robustness of a well-calibrated LR system. Furthermore, the proposed machine learning score-based LRs for specific source problems show that robust performance is achievable even when data for a specific source is scarce [23]. This contrasts with the known variability in performance across individual examiners in traditional pattern evidence disciplines.

Logical Coherence: The LR is derived from Bayes' Theorem, providing a "logically correct framework for interpretation of forensic evidence" [22]. It does not infringe on the ultimate issue (e.g., guilt or innocence) but provides the fact-finder with a scientifically sound measure of evidential strength to update their prior beliefs [6].

A significant challenge, however, is ensuring that LRs are meaningful in the context of a specific case. A major critique of methods that pool data across examiners is that the resulting LR may not reflect the performance of the specific examiner involved in the case [22]. Similarly, the conditions of the case (e.g., quality of the evidence) must be reflected in the data used to generate the LR. Ongoing research, such as Bayesian methods for incorporating individual examiner performance data, aims to address these critical limitations [22].

The evaluation of forensic evidence is undergoing a fundamental transformation, moving from subjective expert opinions toward a rigorous, quantitative framework based on statistical reasoning. This shift centers on the comparison between traditional methods and the likelihood ratio (LR) approach, which formally incorporates the concepts of prior odds, posterior odds, and the weight of evidence. Where traditional interpretation often relied on categorical match/no-match decisions, the Bayesian framework quantifies how observed evidence should update beliefs about competing propositions [6]. This paradigm is increasingly applied across forensic disciplines, from DNA analysis to materials comparison such as vehicle glass, providing a transparent and logically sound method for communicating evidential strength to courts and juries [24].

At the heart of this framework lies Bayes' Theorem, which describes how prior beliefs (prior odds) are updated by new evidence (likelihood ratio) to form revised beliefs (posterior odds). Understanding these core terminologies and their interrelationships is essential for researchers and practitioners aiming to implement statistically valid and defensible evidence evaluation protocols.

Core Terminology and Theoretical Framework

Foundational Definitions

Prior Odds: The ratio of the probabilities of two competing hypotheses (Hâ‚ and Hâ‚‚) before considering the new evidence. It represents the initial state of knowledge or belief based on existing information alone. Mathematically, Prior Odds = P(Hâ‚) / P(Hâ‚‚) [25].

Posterior Odds: The ratio of the probabilities of the same two hypotheses after considering the new evidence. It represents the updated state of belief. The relationship is given by: Posterior Odds = Prior Odds × Likelihood Ratio [26].

Likelihood Ratio (LR) - The "Weight of Evidence": The factor that updates the prior odds to the posterior odds. It measures the relative support the evidence provides for one hypothesis versus the other. The formula is LR = P(E|Hâ‚) / P(E|Hâ‚‚), where P(E|H) is the probability of observing the evidence E if the hypothesis H is true [6]. The LR is the core of the "weight of evidence," directly quantifying how much the evidence should shift our beliefs.

The Bayesian Inference Engine

The relationship between these components is elegantly captured by Bayes' Theorem in its odds form:

Posterior Odds = Prior Odds × Likelihood Ratio [26]

This formula acts as an "inference engine," showing how rational belief is updated in the face of new data. The likelihood ratio is the mechanism through which the evidence exerts its force on our prior beliefs. A LR greater than 1 supports Hâ‚, a LR less than 1 supports Hâ‚‚, and a LR equal to 1 means the evidence is uninformative as it does not change the prior odds [27].

Figure 1: The Bayesian updating process, showing how prior odds are updated by the likelihood ratio to form posterior odds.

Comparative Analysis: LR Framework vs. Traditional Methods

The adoption of the Likelihood Ratio framework represents a significant methodological shift from traditional forensic interpretation. The table below summarizes the key distinctions.

Table 1: Comparison between Traditional Forensic Interpretation and the Likelihood Ratio Framework

| Aspect | Traditional Interpretation | Likelihood Ratio Framework |

|---|---|---|

| Output | Categorical (Match/Inconclusive/No-Match) [24] | Continuous measure of evidential strength (LR Value) [24] |

| Role of Scientist | May directly state conclusions about propositions | Provides weight of evidence to the court; separates scientific evidence from prior odds [6] |

| Handling of Uncertainty | Often implicit and qualitative | Explicitly quantified through probabilities |

| Information Used | Typically focuses on the similarity between samples | Considers both similarity and typicality (rarity of characteristics) |

| Logical Foundation | Less formalized and potentially prone to contextual bias | Based on the established axioms of probability theory |

| Communication | Potentially ambiguous (e.g., "consistent with") | Structured verbal scales linked to numerical LR ranges |

A key advantage of the LR framework is its clear separation of roles. The forensic scientist's task is to evaluate the evidence and provide the LR, which is the weight of evidence. The prior odds, which incorporate other case-specific information (e.g., non-scientific evidence), are the domain of the judge or jury. This prevents the scientist from encroaching on the ultimate issue and maintains the logical structure of the legal process [6].

Experimental Protocols and Data

Case Study: Vehicle Glass Evidence

A 2025 interlaboratory study provides a robust example of the LR framework applied to forensic casework. The study involved 13 laboratories analyzing vehicle glass samples using Laser Ablation Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS) to build background databases and calculate LRs for comparisons [24].

- Experimental Protocol: The standard test method (ASTM E2927-23) was followed for the forensic analysis and comparison of vehicle glass. Participinating laboratories used LA-ICP-MS to characterize the elemental composition of glass fragments.

- Database Construction: Five different international databases, both individually and in combination, were used as background data to calculate LRs. This was critical for assessing the typicality of the compared glass evidence.

- Proposition Formulation: For each casework scenario, two propositions were formulated:

- Hâ‚: The glass originated from the same source.

- Hâ‚‚: The glass originated from different sources.

Performance Metrics and Results

The study evaluated the performance of both the traditional ASTM match criterion and the LR method, yielding the following quantitative results.

Table 2: Performance comparison of ASTM match criterion vs. Likelihood Ratio method for vehicle glass evidence [24]

| Metric | ASTM Match Criterion | Likelihood Ratio Method |

|---|---|---|

| Same-Source Accuracy | Correctly reported "indistinguishable" by most labs | Large LR values (≈ 10,000) providing "strong support" for same-source |

| Different-Source Accuracy | Most reported "distinguishable" | Very small LR values (≈ 0.0001) providing "strong support" for different-source |

| False Inclusion Rate | ~20% (mostly from chemically similar samples) | ROME-ss (Rate of Misleading Evidence) < 2% |

| False Exclusion Rate | ~7% | ROME-ds < 21% (0% if chemically similar samples excluded) |

| Calibration (Cllr) | Not Applicable | < 0.02 (Excellent calibration) |

The data demonstrates that the LR method provides a quantifiable, transparent, and well-calibrated measure of evidential strength. The "Rate of Misleading Evidence" (ROME) is a more nuanced performance metric than simple error rates, as it acknowledges that the probative value of evidence exists on a continuum.

Implementing the LR framework in practice requires specific tools and resources. The following list details key "research reagent solutions" and their functions in this context.

Table 3: Essential materials and resources for implementing a Likelihood Ratio framework

| Tool/Resource | Function in the LR Framework |

|---|---|

| Reference Databases | Populated with background population data (e.g., vehicle glass compositions) to estimate the probability of observing the evidence under the different-source proposition (Hâ‚‚) [24]. |

| Probabilistic Genotyping Software | Software designed to compute likelihood ratios for complex DNA mixtures, accounting for biological models and uncertainty [6]. |

| Calibrated Measurement Instruments | Analytical tools like LA-ICP-MS that provide reliable, quantitative data on material properties (elemental composition, physical properties) for evidence characterization [24]. |

| Statistical Software Packages | Environments (e.g., R, Python with SciPy) used to build statistical models, calculate probability densities, and compute final likelihood ratios. |

| Verbal Equivalence Scales | Standardized tables that map ranges of LR values to verbal statements of support (e.g., "moderate," "strong") to aid communication to fact-finders. |

The transition from traditional forensic interpretation to a framework built on prior odds, posterior odds, and the likelihood ratio represents a critical advancement in forensic science. This paradigm offers a logically rigorous, transparent, and quantifiable method for evaluating evidence, firmly grounded in probability theory. The experimental data from fields like glass analysis demonstrates its practical superiority in characterizing the true weight of evidence while effectively managing uncertainty. For researchers and practitioners, mastering these core terminologies and their application is no longer a specialist interest but a fundamental competency for conducting and presenting scientifically valid forensic research.

LRs in Action: Methodologies from Diagnostics to Drug Safety

The interpretation of complex evidence, whether in a clinical setting or a forensic laboratory, hinges on robust statistical frameworks. The Likelihood Ratio (LR) has emerged as a powerful tool for this purpose, quantifying how much a particular finding—be it a diagnostic test result or a forensic DNA profile—should shift our belief in a given hypothesis. In both medicine and forensic science, practitioners have traditionally relied on more intuitive, yet often less informative, metrics such as sensitivity/specificity or random match probabilities. However, the LR provides a coherent and mathematically sound framework for updating the probability of a hypothesis based on new evidence, rooted firmly in Bayes' theorem [28] [29].

This guide explores the pivotal role of the LR, with a specific focus on simplifying its interpretation for practical use. We will objectively compare the performance of traditional methods against modern LR-based approaches, particularly in the complex and consequential field of forensic science. The transition from traditional methods represents a significant leap in investigative capability, moving from subjective assessments to continuous, probabilistic interpretations that can handle complex, mixed, or low-quality samples with greater statistical rigor [9] [30]. By framing this discussion within a broader thesis on LR versus traditional forensic interpretation, this article provides researchers and scientists with the practical tools and comparative data needed to evaluate these methodologies.

Understanding the Likelihood Ratio: Core Concepts and Calculations

Definition and Formulae

A Likelihood Ratio is a measure of diagnostic accuracy that compares the probability of observing a specific piece of evidence under two competing hypotheses. In a clinical context, these hypotheses are typically the presence of disease versus its absence. The LR seamlessly combines the concepts of sensitivity and specificity into a single, more clinically useful metric [28] [29].

Positive Likelihood Ratio (LR+): This indicates how much the odds of a disease increase when a test is positive. It is calculated as the probability of a positive test in diseased individuals divided by the probability of a positive test in non-diseased individuals [29] [4].

LR+ = Sensitivity / (1 - Specificity)

Negative Likelihood Ratio (LR-): This indicates how much the odds of a disease decrease when a test is negative. It is calculated as the probability of a negative test in diseased individuals divided by the probability of a negative test in non-diseased individuals [29] [4].

LR- = (1 - Sensitivity) / Specificity

The power of the LR lies in its direct application through Bayes' theorem. It allows the clinician to move from a pre-test probability to a post-test probability using the relationship: Post-test Odds = Pre-test Odds × Likelihood Ratio [28] [29]. This process transforms a subjective clinical suspicion into a quantitative probability, refining diagnostic decision-making.

Interpreting Likelihood Ratio Values

The value of the LR itself provides immediate, intuitive insight into the diagnostic strength of a finding [28] [29] [4]:

- LR > 1: The finding is associated with the presence of the disease. The further the LR is above 1, the stronger the evidence for the disease.

- LR = 1: The finding does not change the probability of disease; the test is uninformative.

- LR < 1: The finding is associated with the absence of the disease. The closer the LR is to 0, the stronger the evidence against the disease.

As a rule of thumb, LRs greater than 10 or less than 0.1 are considered to provide strong, and often conclusive, evidence to rule in or rule out diagnoses, respectively. LRs between 5-10 and 0.1-0.2 offer moderate evidence, while those closer to 1 have limited diagnostic value [28] [29].

Simplifying LR Interpretation: Practical Estimation Methods

The Challenge of Calculation

A significant barrier to the widespread clinical use of LRs is the computational step required to convert between probabilities and odds, a process unfamiliar to many clinicians. The conventional application requires three steps: converting pre-test probability to pre-test odds, multiplying by the LR to get post-test odds, and then converting post-test odds back to post-test probability [31]. This process, while mathematically sound, is cumbersome without a calculator or nomogram at the bedside.

The Simplified Estimation Table

To overcome this barrier, a simplified method was developed that provides approximate changes in probability based on the LR value, eliminating the need for calculations and easily memorized [31]. This method is accurate to within 10% of the calculated answer for all pre-test probabilities between 10% and 90%, with an average error of only 4%.

Table 1: Approximate Change in Probability Based on Likelihood Ratio

| Likelihood Ratio | Approximate Change in Probability |

|---|---|

| 0.1 | -45% |

| 0.2 | -30% |

| 0.3 | -25% |

| 0.4 | -20% |

| 0.5 | -15% |

| 1 | 0% |

| 2 | +15% |

| 3 | +20% |

| 4 | +25% |

| 5 | +30% |

| 6 | +35% |

| 8 | +40% |

| 10 | +45% |

This table can be easily recalled by remembering three benchmark LRs and their corresponding probability shifts: an LR of 2 increases probability by ~15%, an LR of 5 by ~30%, and an LR of 10 by ~45%. For LRs between 0 and 1, the same estimates are used for the decrease in probability by taking the inverse of the LR (e.g., LR of 0.5, the inverse of 2, decreases probability by ~15%) [31] [4].

Worked Example of Simplified Estimation

Consider a patient with abdominal distension where the clinician's initial estimate (pre-test probability) for ascites is 40%. The physical sign of "bulging flanks" has an LR+ of 2.0 for ascites.

- Traditional Method: Pre-test probability (40%) converts to pre-test odds of 0.4/(1-0.4) = 0.667. Post-test odds = 0.667 × 2.0 = 1.333. Post-test probability = 1.333/(1+1.333) = 57%.

- Simplified Method: From Table 1, an LR of 2 corresponds to an approximate +15% increase in probability. The estimated post-test probability is therefore 40% + 15% = 55%.

The simplified method provides an estimate of 55%, which is only 2% different from the calculated probability of 57%, demonstrating its practical utility and sufficiency for clinical decision-making [31].

LR in Forensic Science: A Paradigm Shift from Traditional Interpretation

The Limitation of Traditional Forensic Methods

Traditional forensic methods have long been the backbone of criminal investigations. These include techniques such as fingerprint analysis, bloodstain pattern analysis, ballistics, and handwriting analysis [9]. While effective in their time, these methods often rely on manual examination and subjective interpretation by experts. The reliability of these methods can be questioned due to their dependence on human skill and experience, which can lead to varying conclusions [9] [32]. Furthermore, these methods are primarily designed for tangible, physical evidence and struggle with the complexity and volume of modern digital data [32].

In the specific domain of DNA analysis, traditional statistical methods like the Combined Probability of Inclusion (CPI) or Random Match Probability (RMP) were applied to DNA profiles. However, these methods often failed to account for the complexities of modern DNA evidence, such as low-level, degraded, or mixed DNA samples from multiple contributors. To handle uncertainty, these methods sometimes involved omitting data from loci where allelic drop-out was suspected, risking either an underestimation of the evidence's strength or the false inclusion of a potential contributor [33].

The Modern LR Framework in Forensics

Modern forensic science has increasingly adopted a probabilistic approach using the LR framework to overcome these limitations [30] [33]. This shift is part of a larger evolution towards digitalization and automation, which also encompasses mobile forensics, cloud forensics, and the analysis of data from drones and IoT devices [32].

In the context of DNA, the LR framework allows scientists to quantitatively assess the strength of evidence by comparing two probabilities [33] [34]:

LR = Probability of the Evidence given the Prosecution's Hypothesis (Hâ‚€) / Probability of the Evidence given the Defense's Hypothesis (Hâ‚)

For example, Hâ‚€ might be "The suspect is the source of the DNA profile," while Hâ‚ might be "A random individual is the source of the DNA profile." The LR explicitly accounts for real-world complexities like allelic drop-out (where an allele fails to be detected) and drop-in (the random appearance of an allele from contamination) by incorporating their probabilities into the calculation [33]. Unlike traditional methods, the LR framework does not require discarding data and provides a transparent and logically coherent measure of evidential strength.

Comparative Performance: Traditional vs. LR-Based Forensic Methods

Experimental Protocols and Software Tools

The adoption of the LR framework in forensic DNA analysis has been facilitated by the development of specialized software that automates the complex calculations involved. Two leading software solutions are STRmix and Lab Retriever, each embodying the modern approach to forensic interpretation [30] [33].

Table 2: Key Software for Forensic Likelihood Ratio Calculation

| Software | Core Functionality | Methodology | Scope of Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| STRmix | Resolves low-level, degraded, or mixed DNA samples. | Uses continuous probabilistic modeling to calculate LRs for the observed evidence under different propositions. | Used in 119 forensic labs globally (including the FBI and ATF); applied in >690,000 cases. |

| Lab Retriever | Calculates LRs for complex DNA profiles, incorporating probabilities for drop-out and drop-in. | An open-source tool with a GUI that implements a modified Balding-Buckleton algorithm for speed and accessibility. | Freely available for forensic scientists to assess the statistical weight of complex DNA evidence. |

STRmix Experimental Workflow: The software assesses how closely millions of potential DNA profiles explain the observed DNA mixture. It uses proven mathematical methodologies from computational biology and physics to compute the probability of the observed evidence assuming it originated from either a person of interest or an unknown donor. These two probabilities are then presented as a LR [30].

Lab Retriever Experimental Workflow: The user must input the evidence profile, the genotype of the suspect, the number of contributors, and parameters for drop-out, drop-in, and co-ancestry. The software then computes the LR by calculating the probability of the evidence given the suspect's profile and the probability of the evidence given a random person's profile, summing over all possible genotypes for the unknown contributor(s) [33].

The following diagram illustrates the core logical relationship shared by these forensic LR systems:

Performance and Adoption Data

The performance of modern LR-based systems is often evaluated using metrics like the Log Likelihood Ratio Cost (Cllr). This metric penalizes misleading LRs (those on the wrong side of 1) more heavily, with Cllr = 0 indicating a perfect system and Cllr = 1 indicating an uninformative system [34].

Comparative analysis shows that LR-based methods offer significant advantages over traditional approaches:

- Handling Complexity: LR methods can objectively interpret complex DNA mixtures that are intractable for traditional CPI/RMP methods [30] [33].

- Statistical Robustness: They provide a scientifically rigorous and legally defensible weight of evidence, avoiding the "conservative" underestimation or potential for false inclusion associated with older methods [33].

- Efficiency and Scale: Software like STRmix has been used to interpret DNA evidence in over 690,000 cases worldwide, demonstrating its practical utility and reliability in high-volume, real-world environments [30].

A study of 136 publications on automated LR systems found that while the use of these systems is increasing, Cllr values can vary substantially depending on the forensic analysis type and dataset, indicating that performance is context-specific [34]. This underscores the importance of using standardized benchmark datasets for fair comparisons, an area where the field continues to develop.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Research Solutions

The experimental protocols for implementing LR systems, particularly in forensic DNA analysis, require a suite of specialized tools and reagents. The following table details key components of this research toolkit.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Forensic LR Analysis

| Research Tool / Reagent | Function in LR Analysis |

|---|---|

| Genetic Analyzer | A core hardware platform used to generate raw DNA electrophoregram data from samples. This raw data is the fundamental "evidence" that software like STRmix or Lab Retriever interprets. |

| Standard Profiling Kits | Commercial kits (e.g., STR multiplex kits) containing primers and reagents to amplify specific DNA markers. They standardize the input data for probabilistic genotyping software. |

| Probabilistic Genotyping Software (e.g., STRmix, Lab Retriever) | The core software that performs the LR calculation. It uses mathematical models to compute the probability of the observed genetic data under competing hypotheses about the contributors to the sample. |

| Allele Frequency Database | A population-specific dataset of allele frequencies that is crucial for calculating the probability of the evidence under the "random individual" hypothesis (Hâ‚) in the denominator of the LR. |

| Parameters (P(DO), P(DC), θ) | Key user-defined parameters: Drop-out Probability (P(DO)), the probability an allele is not detected; Drop-in Probability (P(DC)), the probability of a contaminant allele; and Theta (θ), a co-ancestry coefficient to account for population substructure. |

| TG53 | TG53, CAS:946369-04-6, MF:C21H22ClN5O2, MW:411.9 g/mol |

| Uvaol | Uvaol, CAS:545-46-0, MF:C30H50O2, MW:442.7 g/mol |

The journey toward simplifying and standardizing the interpretation of Likelihood Ratios represents a critical advancement in both clinical diagnostics and forensic science. The practical estimation tables provide clinicians with an immediate, calculation-free method to update diagnostic probabilities, thereby enhancing bedside decision-making. Simultaneously, the paradigm shift from traditional forensic methods to modern, LR-based probabilistic systems has fundamentally improved the scientific rigor, transparency, and statistical validity of evidence interpretation in the courtroom.

While challenges remain—such as the need for standardized benchmarks in forensic evaluation and the subjective estimation of pre-test probability in medicine—the direction of progress is clear. The continued development and validation of software tools like STRmix and Lab Retriever, coupled with a deeper understanding of simplified LR interpretation, empower researchers and professionals across disciplines to more accurately and reliably quantify the strength of evidence. This, in turn, strengthens the foundations of evidence-based practice in medicine and justice.

Drug safety signal detection represents a critical safeguard in pharmacovigilance (PV), aiming to identify unexpected patterns in adverse event data that suggest new drug-related risks [35]. Traditionally, this field has relied on established statistical measures including disproportionality analysis methods such as Proportional Reporting Ratios (PRR) and Reporting Odds Ratios (ROR) [36] [35]. While these methods are widely implemented in systems like the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) and WHO's VigiBase, which contains over 40 million safety reports, they primarily function as screening tools that highlight statistical associations without directly quantifying evidence strength [35].

In contrast, Likelihood Ratio (LR) methods offer a fundamentally different approach rooted in formal statistical inference and evidence measurement. Originally developed for forensic DNA evaluation, the LR framework provides a mathematically rigorous means to quantify the strength of evidence for or against a specific hypothesis [37] [34]. This methodological paradigm measures how much more likely the observed data (adverse event reports) is under the hypothesis that a drug-adverse event association exists compared to the hypothesis that no association exists. The core advantage of this approach lies in its ability to directly quantify evidentiary strength, making it particularly valuable for proactive risk management in complex, multi-study environments where traditional methods may struggle with heterogeneity across data sources [36].

LR Methodologies: Technical Foundations and Experimental Protocols

Core Computational Framework

The fundamental LR framework for drug safety surveillance builds upon a probabilistic comparison of observed versus expected reporting patterns. For a specific drug i and adverse event j, the test statistic is derived from a Poisson model where the cell count nij represents the number of reported cases for the drug-event pair, with ni. indicating total reports for the drug, n.j representing total reports for the adverse event, and n.. signifying the total reports in the database [36].

The likelihood ratio statistic is computed as:

LRij = [ (nij/ni.)^nij * ((n.j - nij)/(n.. - ni.))^(n.j - nij) ] / [ (n.j/n..)^n.j ]

This can be conveniently rewritten using expected values:

LRij = (nij/Eij)^nij * [(n.j - nij)/(n.j - Eij)]^(n.j - nij)

Where Eij = (ni. * n.j)/n.. represents the expected count under the null hypothesis of no association [36].

For practical implementation, researchers typically work with the log-likelihood ratio, which transforms the product into a sum and provides numerical stability:

log(LRij) = nij * [log(nij) - log(Eij)] + (n.j - nij) * [log(n.j - nij) - log(n.j - Eij)] - n.j * [log(n.j) - log(n..)] [36]

Experimental Protocols for Multi-Study Applications

The implementation of LR testing in drug safety surveillance follows structured experimental protocols that vary based on data availability and research objectives:

Protocol 1: Simple Pooled LRT for Multi-Study Analysis

This approach involves applying the regular LRT to safety data from each study individually, then combining the test statistics across studies to derive an overall test statistic for a global hypothesis test [36]. The methodology proceeds as follows:

- Data Preparation: Organize data into multiple 2×2 contingency tables stratified by study, with drugs as rows and adverse events as columns

- Study-Level Analysis: Compute regular LRT statistics for each study independently

- Results Combination: Combine LRT statistics across studies using appropriate meta-analytic techniques

- Global Testing: Evaluate the combined statistic against a pre-specified significance level to detect signals

This method is particularly valuable when analyzing integrated safety data from multiple clinical trials or observational studies, such as in the evaluation of Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs) with concomitant use in osteoporosis patients across 6 studies [36].

Protocol 2: Weighted LRT Incorporating Drug Exposure

When drug exposure information is available, the weighted LRT method enhances the basic approach by incorporating exposure metrics [36]:

- Exposure Adjustment: Replace simple report counts (ni.) with actual exposure measures (Pi), such as total dose or patient-time exposure

- Consistent Metric Definition: Ensure exposure definitions are consistent and comparable across different studies in the meta-analysis

- Rate Calculation: Compute reporting rates adjusted for actual drug exposure rather than simple report counts

- Statistical Testing: Apply the LRT framework to these exposure-adjusted rates

This protocol was successfully applied to Lipiodol (a contrast agent) safety data across 13 published studies with a maximum dose of 15mg, demonstrating the method's practical utility in real-world safety evaluations [36].

Protocol 3: Longitudinal LRT (LongLRT) for Temporal Analysis

For longitudinal clinical trial data or databases with exposure information, the LongLRT method extends the basic framework to incorporate temporal patterns [38]:

- Sequential Data Organization: Structure data to capture adverse event occurrences over time

- Exposure Incorporation: Integrate time-varying exposure metrics

- Sequential Testing: Implement the SeqLRT variant for evaluating signals of specific adverse events for a particular drug compared to placebo or an active comparator

- Performance Monitoring: Assess method performance using conditional power and type I error control over time

This approach has been applied to pooled longitudinal clinical trial datasets for drugs treating osteoporosis with concomitant use of PPIs, demonstrating capability to identify possible evidence of PPIs leading to more adverse events associated with osteoporosis [38].

The following diagram illustrates the workflow for implementing these LR methodologies in drug safety signal detection:

Figure 1: LR Method Implementation Workflow - This diagram illustrates the structured process for implementing likelihood ratio methodologies in drug safety signal detection, from data collection through regulatory decision-making.

Performance Comparison: LR Methods Versus Alternative Approaches