Bayesian Reasoning in Forensic Science: Navigating Evidence Uncertainty from Theory to Practice

This article provides a comprehensive examination of Bayesian reasoning as a framework for addressing uncertainty in forensic evidence.

Bayesian Reasoning in Forensic Science: Navigating Evidence Uncertainty from Theory to Practice

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of Bayesian reasoning as a framework for addressing uncertainty in forensic evidence. Targeting researchers, scientists, and legal professionals, it explores the foundational principles of forensic Bayesianism, details methodological applications including Bayesian networks for complex evidence evaluation, addresses implementation challenges and optimization strategies, and critically assesses validation approaches and comparative effectiveness against traditional methods. The synthesis offers crucial insights for advancing robust, statistically sound practices in forensic science and demonstrates profound implications for evidence interpretation in biomedical and clinical research contexts.

The Foundations of Forensic Uncertainty: Why Bayesian Reasoning Matters

The Crisis of Confidence in Traditional Forensic Science

The forensic science community is currently navigating a critical juncture, marked by growing scrutiny of its traditional methodologies and their application within the criminal justice system [1]. A series of high-profile reports and a expanding body of academic literature have begun to question the validity and reliability of long-established forensic disciplines [1]. This crisis stems not from a single point of failure, but from a complex interplay of operational, structural, and epistemological challenges. These range from the admissibility of expert evidence and a lack of robust error rate data to the fundamental difficulty of communicating the precise value and limitations of forensic evidence to legal practitioners and juries [1]. In response, a paradigm shift is underway, moving away from a focus on organizational processes and tools and toward a reaffirmation of forensic science as a distinct discipline unified by its purpose: to reconstruct, monitor, and prevent crime and security issues [2]. Central to this transformation is the adoption of a Bayesian framework for reasoning about evidence, which provides a structured, transparent, and logically sound method for evaluating forensic findings under conditions of uncertainty.

The crisis of confidence is multifaceted, arising from challenges that touch upon the scientific foundations, practical applications, and legal interpretations of forensic evidence.

Operational and Structural Deficiencies

The journey of forensic evidence from the crime scene to the courtroom is fraught with potential pitfalls. Key operational problems include a documented lack of effective quality control procedures in some bodies providing forensic services, the use of non-unique identifiers for exhibits, and failures in communication between different agencies involved in the process [1]. These operational issues can be exacerbated by structural problems within the legal system itself, including the adversarial nature of common law jurisdictions, which can prioritize winning a case over a neutral scientific inquiry, and the potential for cognitive bias to influence both legal representatives and experts [1]. Such errors can have a cascading effect, where one initial procedural or human error leads to additional cumulative mistakes, potentially culminating in a wrongful conviction [1].

The Admissibility and Reliability of Expert Evidence

A central tension point lies in how expert evidence is admitted and evaluated in court. In some jurisdictions, a "laissez-faire" approach has been reported, where it is rare for forensic evidence to be deemed inadmissible, based on the conviction that its reliability will be effectively challenged during trial [1]. This stands in stark contrast to standards like Daubert, which require the trial judge to act as a gatekeeper to ensure scientific evidence is both relevant and reliable—a task for which many judges are not scientifically prepared [1]. Compounding this is the problem of reliability for forensic disciplines that lack a strong statistical foundation. This is particularly evident in the absence of "ground truth" databases for some branches of forensic science, making it difficult to quantify the accuracy and error rates of methods [1]. While academics often advocate for the statistical quantification of expert opinion as a hallmark of reliability, practitioners may counter that such standards are unnecessary or that statistics are too challenging for juries to understand [1].

Table 1: High-Profile Cases Illustrating Systemic Failures

| Case Name | Forensic Issue | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Cannings [1] | Unreliable expert opinion expressed outside of field expertise. | Wrongful conviction. |

| Clark [1] | Unreliable expert opinion; failure to disclose key information. | Wrongful conviction. |

| Dallagher [1] | Questioned validity and reliability of forensic technique. | Illustrative of admissibility challenges. |

The Epistemological Divide Between Science and Law

Underpinning these practical challenges is a fundamental epistemological clash. Science and law represent different disciplinary traditions with divergent understandings of truth and timelines [1]. As noted in the Daubert decision, “Scientific conclusions are subject to perpetual revision. Law, on the other hand, must resolve disputes finally and quickly” [1]. This divergence creates significant operational challenges when these worlds collide in the courtroom. The forensic scientist acts as an interlocutor, translating the silent testimony of material evidence for the legal forum. The integrity and effectiveness of this "act of translation" are, therefore, paramount to achieving justice [1].

A Bayesian Framework for Rebuilding Confidence

The Bayesian approach to evidence evaluation offers a powerful solution to these challenges by providing a coherent and transparent framework for updating beliefs in the light of scientific findings.

Foundational Principles of Bayesian Reasoning

At its core, Bayesian reasoning provides a formal mechanism for updating the probability of a proposition (e.g., "the suspect is the source of the fibre") based on new evidence. It uses the likelihood ratio (LR) to quantify the strength of the evidence, comparing the probability of observing the evidence under the prosecution's proposition to the probability of observing it under the defense's proposition. This process forces explicit consideration of the alternative scenarios and the role of the evidence in distinguishing between them, thereby mitigating the risk of cognitive bias and providing a clear, auditable trail for the reasoning process.

Methodological Protocols for Bayesian Network Construction

The application of Bayesian reasoning is effectively operationalized through Bayesian Networks (BNs), which are graphical models representing the probabilistic relationships among variables in a case. The following protocol outlines the construction of a narrative BN for activity-level evaluation, a methodology designed to be accessible for practitioners [3].

Protocol 1: Constructing a Narrative Bayesian Network for Activity-Level Propositions

- Objective: To transparently model the complex factors involved in evaluating forensic evidence given activity-level propositions (e.g., "Did the suspect come into contact with the victim?" versus "Is there an innocent explanation for the transfer?").

- Materials: Case information, evidence reports, relevant data on transfer, persistence, and background levels of materials.

- Procedure:

- Define the Key Propositions: Start by clearly defining the prosecution (Hp) and defense (Hd) propositions at the activity level. These form the top-level hypotheses in the network.

- Identify Relevant Case Factors: List all case circumstances and factors that could influence the probability of the evidence. For transfer evidence like fibres, this includes:

- Transfer Mechanisms: The probability of primary, secondary, or tertiary transfer.

- Persistence & Recovery: The probability that a transferred material persists on a substrate and is successfully recovered by investigators.

- Background Presence: The probability of finding the same material on a given substrate by chance in the relevant environment.

- Develop the Network Structure (Narrative Model): Create a directed acyclic graph where nodes represent the propositions and case factors, and arrows represent probabilistic dependencies. The model should tell the "story" of the case, aligning with how events might have unfolded.

- The top-level

Activitynode is parent to aTransfernode. - The

Transfernode is a parent to aBackgroundnode (representing the possibility of the material being present regardless of the activity) and aDetectionnode. - The

Detectionnode represents the analytical process of finding and identifying the material.

- The top-level

- Populate the Probability Tables: For each node, define a conditional probability table (CPT) based on empirical data, validation studies, or informed expert judgment. These tables quantitatively encode the relationships between nodes.

- Enter Case Findings: Instantiate the network with the specific findings of the case (e.g., "Fibres were found").

- Sensitivity Analysis: Run the model to calculate the likelihood ratio and perform sensitivity analysis to assess how the results are affected by variations in the underlying probabilities, highlighting which factors are most critical to the outcome.

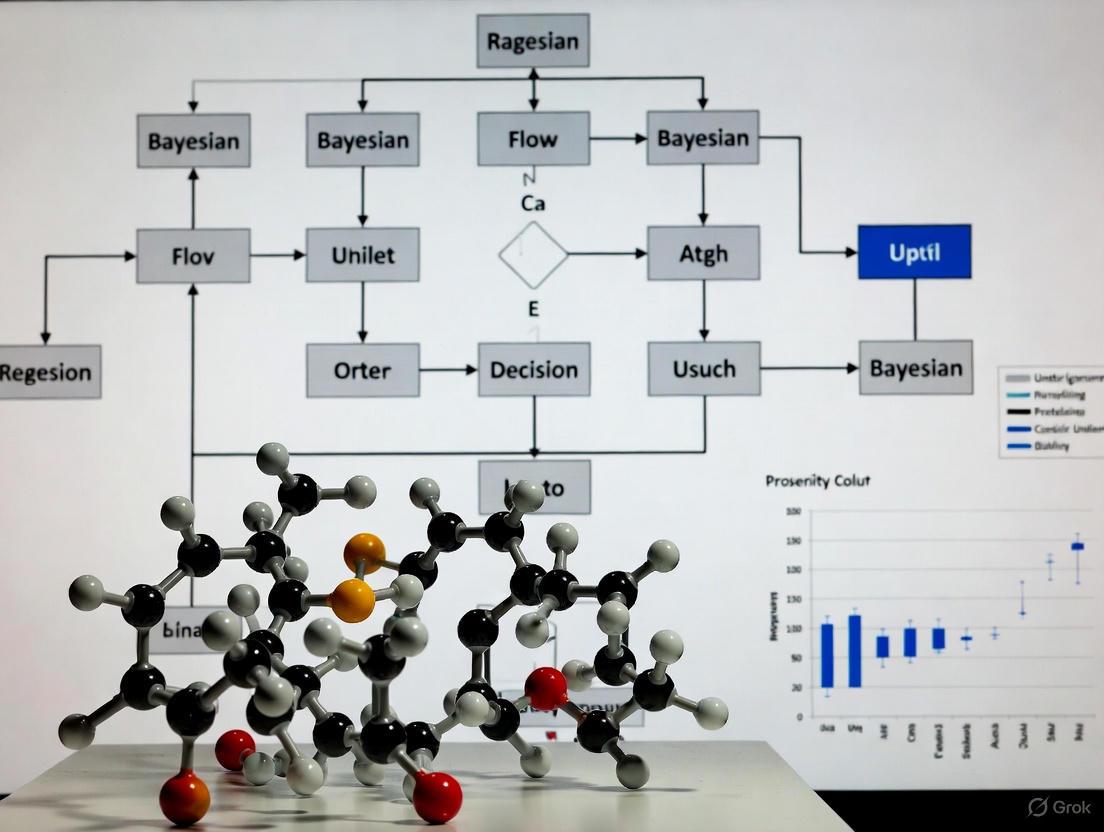

The following diagram visualizes the core logical structure of a narrative Bayesian network for a simple transfer scenario.

Advanced Bayesian Modeling for Interdisciplinary Cases

For more complex cases involving multiple activities or a dispute about the relation of an item to an activity, a template BN can be constructed to enable a combined evaluation [4]. This is particularly useful in interdisciplinary casework where evidence from different forensic disciplines must be integrated.

Protocol 2: Template Bayesian Network for Interdisciplinary Evidence Evaluation

- Objective: To evaluate transfer evidence where the relation between an item of interest and one or more alleged activities is contested, combining evidence concerning the suspect's activities and the use of an alleged item.

- Materials: As in Protocol 1, with additional data streams from multiple forensic disciplines (e.g., fibres and DNA).

- Procedure:

- Define Association Propositions: Establish a set of propositions that link the suspect to an activity (

Activity_S) and the activity to a specific item (Item_A). - Construct a Unified Network: Build a BN that incorporates nodes for both the suspect's activity and the item's use. The network should include separate but connected sub-models for each stream of evidence (e.g., fibre transfer and DNA transfer).

- Incorporate a "Relation" Node: Include a node that represents the disputed relation between the item and the activity, which is informed by the evidence from the different disciplines.

- Parameterize with Disciplinary Data: Populate the conditional probability tables for each evidence sub-model using discipline-specific data and knowledge.

- Run Combined Evaluation: Enter the findings from all forensic disciplines to compute a combined likelihood ratio that assesses the overall strength of the evidence for the joint propositions.

- Define Association Propositions: Establish a set of propositions that link the suspect to an activity (

The DOT script below defines the more complex structure of an interdisciplinary template Bayesian network.

Advancing the field requires not only new methodologies but also access to robust data, protocols, and computational tools. The following table details key resources for researchers in this domain.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Bayesian Forensic Science

| Resource / Tool | Type | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Ground Truth Databases [1] | Database | Provides empirical data on transfer, persistence, and background levels of materials (e.g., fibres, DNA) essential for populating conditional probability tables in BNs. |

| NIST OSAC Registry [5] | Standards Repository | A collection of 225+ validated forensic science standards (e.g., from ASB, SWGDE) that ensure methodological consistency and support the validity of inputs used in BN models. |

| Forensic Science Strategic Research Plan (NIJ) [6] | Strategic Framework | Guides research priorities, including foundational research on the validity of methods and understanding evidence limitations under activity-level propositions. |

| Bayesian Network Software (e.g., GeNIe, Hugin) | Computational Tool | Provides a user-friendly environment for constructing, parameterizing, and running complex Bayesian network models for evidence evaluation. |

| Current Protocols in Bioinformatics [7] | Method Protocol | Offers peer-reviewed laboratory and computational protocols, including those relevant to forensic bioinformatics and statistical analysis. |

| Springer Protocols [7] | Method Protocol | A vast collection of laboratory methods in biomedical sciences, useful for developing and validating foundational forensic techniques that feed into BN models. |

Future Directions and Strategic Alignment

The shift towards Bayesian frameworks and a purpose-driven discipline is reflected in the strategic agendas of leading forensic science organizations. The National Institute of Justice (NIJ) Forensic Science Strategic Research Plan, 2022-2026 explicitly prioritizes research that supports this evolution [6]. Key objectives that align with addressing the crisis of confidence include:

- Foundational Validity and Reliability (Priority II.1): Understanding the fundamental scientific basis of forensic disciplines and quantifying measurement uncertainty [6].

- Decision Analysis (Priority II.2): Measuring the accuracy and reliability of forensic examinations through black-box and white-box studies and evaluating human factors [6].

- Understanding the Limitations of Evidence (Priority II.3): Researching the value of forensic evidence beyond individualization to include activity-level propositions [6].

- Standard Criteria for Interpretation (Priority I.6): Evaluating the use of methods, such as likelihood ratios, to express the weight of evidence [6].

Table 3: NIJ Strategic Research Priorities Relevant to the Confidence Crisis

| Strategic Priority | Key Objectives | Impact on Confidence Crisis |

|---|---|---|

| II.1: Foundational Validity & Reliability [6] | Quantify measurement uncertainty; Understand scientific basis of methods. | Provides the empirical data needed to justify and parameterize Bayesian models, strengthening scientific foundation. |

| II.2: Decision Analysis [6] | Measure accuracy (black-box studies); Identify sources of error (white-box studies). | Directly tests and validates the performance of forensic methods and examiners, generating data for error rates. |

| II.3: Understanding Evidence Limitations [6] | Research value of evidence under activity-level propositions. | Promotes the adoption of the Bayesian framework for a more nuanced and accurate evidence evaluation. |

| I.6: Standard Interpretation Criteria [6] | Evaluate likelihood ratios and verbal scales for expressing evidence weight. | Encourages a standardized, logically robust method for reporting, improving communication to the court. |

The crisis of confidence in traditional forensic science is a profound challenge, but it also presents an opportunity for foundational renewal. By confronting the operational, structural, and epistemological sources of uncertainty head-on, the discipline can rebuild its scientific credibility. The adoption of Bayesian reasoning, implemented through narrative and template Bayesian networks, provides a rigorous, transparent, and logically sound methodology for evaluating evidence under activity-level propositions. This approach directly addresses key weaknesses in the traditional paradigm by forcing explicit consideration of alternative scenarios, incorporating empirical data on transfer and background, and providing a quantifiable measure of evidential strength. Supported by strategic research initiatives and a growing toolkit of resources, the integration of Bayesian frameworks heralds a future for forensic science that is more scientifically robust, transparent, and reliably informative for the courts.

The evolution of reasoning under uncertainty in forensic science represents a paradigm shift from qualitative diagrams to quantitative probabilistic frameworks. This transition is characterized by the integration of argument maps, which provide intuitive visual structure, with Bayesian networks, which offer rigorous computational inference. The Bayesian framework has emerged as a cornerstone for the evaluation of forensic evidence, enabling researchers to address the complexities of evidence uncertainty with mathematical precision [8]. This technical guide examines this methodological evolution, detailing the formalisms, comparative advantages, and implementation protocols that define modern forensic reasoning.

Foundational Formalisms

Wigmore Charts: Qualitative Argument Mapping

Wigmore Charts, introduced in the early 20th century, serve as a graphical method for organizing legal arguments and evidence [9]. Their primary function is to structure complex reasoning processes through a visual topology of interconnected elements.

- Core Components: The chart comprises two fundamental entity types: evidences (premises) and assumptions (conclusions). The final assumption represents the ultimate conclusion to be proven [9].

- Visual Syntax: The methodology employs specific symbols to categorize evidence types: rectangles for physical evidence, punched tape for witness testimony, parallelograms for victim statements, stored data for expert conclusions, internal storage for investigation records, and cards for audiovisual materials [9].

- Inferential Process: The framework operates through two distinct phases: assumption recognition (identifying potential conclusions from case facts) and assumption proof (evaluating assumptions through supporting and opposing evidences) [9].

- Functional Limitations: Despite their structural utility for qualitative reasoning, Wigmore Charts lack computational mechanisms for quantitative analysis, rendering them unsuitable for probabilistic assessment of argument strength [9].

Bayesian Networks: Quantitative Probabilistic Reasoning

Bayesian Networks (BNs) represent a probabilistic graphical model that encodes variables and their conditional dependencies via directed acyclic graphs. This formalism provides a mathematical foundation for reasoning under uncertainty in forensic contexts.

- Graphical Structure: BNs consist of nodes (representing random variables) and directed edges (representing conditional dependencies), forming a network that captures causal and evidential relationships [10].

- Numerical Semantics: Each node associates with a conditional probability table that quantifies the stochastic relationships between connected variables, enabling precise calculation of posterior probabilities given observed evidence [9].

- Inferential Capabilities: The network supports both deductive ("forward") and abductive ("backward") inference, allowing experts to reason from causes to effects or from observations to explanations [10].

- Implementation Challenges: While offering robust quantitative reasoning, BNs demand significant mathematical expertise and can obscure the intuitive narrative structure essential for legal communication [3].

The Methodological Evolution

Bridging Formalisms: Intermediate Approaches

Research efforts have focused on developing hybrid approaches that integrate the strengths of both Wigmore Charts and Bayesian Networks.

- Information Graphs (IGs): This formalism provides a precise account of the interplay between deductive and abductive inference, serving as an intermediary representation between informal reasoning tools and fully quantitative BNs [10].

- Case Description Model Based on Evidence (CDMBE): This approach combines Wigmore's visual intuition with Bayesian calculability, defining five syntagmatic relationships (conjunction, recombination, aggregation, reinforcement, and coupling) with associated computational formulas [9].

- Narrative Bayesian Networks: These simplified constructions emphasize transparent incorporation of case information, enhancing accessibility for practitioners and legal professionals while maintaining mathematical rigor [3].

Comparative Analysis: Formalisms and Applications

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Reasoning Formalisms in Forensic Science

| Aspect | Wigmore Charts | Intermediate Models | Bayesian Networks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Qualitative argument organization | Bridging qualitative and quantitative reasoning | Quantitative probabilistic inference |

| Reasoning Type | Defeasible logic | Defeasible logic with calculability | Probabilistic reasoning |

| Visualization | High - specialized symbols for evidence types | Moderate-high - simplified representations | Moderate - standard graph notation |

| Calculability | None | Defined formulas for credibility propagation | Conditional probability tables |

| Mathematical Demand | Low | Moderate | High |

| Legal Narrative | Strong | Maintained through structure | Often obscured by mathematics |

| Best Application | Initial case structuring, thought clarification | Case analysis, knowledge storage | Complex evidence evaluation under uncertainty |

Computational Implementation

The CDMBE Computational Framework

The Case Description Model Based on Evidence implements a calculable framework through defined formulas for evidence integration.

Testimonial Power Calculation: The model defines testimonial power (Pi) for evidence or assumption i with credibility (Ci) and supportability (Si) as:

Pi = (Ci × Si) / (Ci × Si + Ci × (1 - Si) + Si × (1 - Ci)) [9]

This formula mitigates rapid descent of probabilistic strength when both credibility and supportability values are low.

Syntagmatic Relationships: The framework defines five relationship types with associated computational rules:

- Conjunction: All requirements must be proven (logical AND)

- Recombination: Any one evidence can prove assumption (logical OR)

- Aggregation: Combined supporting power from multiple evidences

- Reinforcement: Multiple evidences supporting same assumption

- Coupling: Interdependent evidences [9]

Bayesian Network Construction Methodology

Modern approaches emphasize structured methodologies for BN development in forensic applications.

- Template Models: Simplified BN templates provide starting points for case-specific networks, enhancing accessibility for practitioners [3].

- Activity-Level Evaluation: Specialized networks evaluate findings given activity-level propositions, considering transfer and persistence factors [3].

- Sensitivity Analysis: Networks are designed to assess evaluation sensitivity to variations in input data and assumptions [3].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol: Bayesian Network Construction for Forensic Evaluation

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Bayesian Forensic Modeling

| Component | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Graphical Model | Represent variables and dependencies | Directed acyclic graph with nodes and edges |

| Conditional Probability Tables | Quantify relational strengths | Probability distributions for each node given parents |

| Prior Probabilities | Represent baseline knowledge | Initial probability values for root nodes |

| Software Environment | Enable model construction and inference | Specialized BN software (GeNIe, Hugin, etc.) |

| Sensitivity Analysis Tools | Assess model robustness | Parameter variation and impact analysis |

| Validation Dataset | Verify model performance | Historical case data with known outcomes |

- Case Narrative Development: Document the factual scenario, identifying key events, actions, and potential evidence transfers [3].

- Variable Identification: Define relevant variables representing hypotheses, evidence, and intermediate states, specifying their possible values or states [3].

- Qualitative Structure Construction: Build the network topology by connecting variables based on their causal and evidential relationships [10].

- Quantitative Parameterization: Populate conditional probability tables using empirical data, expert judgment, or logical constraints [3].

- Model Validation: Verify network behavior against known cases or logical expectations, ensuring proper propagation of probabilities [3].

- Evidence Integration: Enter specific evidence into the network and calculate posterior probabilities for hypotheses of interest [9].

- Sensitivity Analysis: Assess how changes in input parameters affect the resulting conclusions, identifying critical assumptions [3].

Workflow Visualization: From Evidence to Inference

Diagram 1: Evidence Integration Workflow (76 characters)

Contemporary Applications and Research Frontiers

Advanced Implementation Domains

Modern Bayesian frameworks have expanded into sophisticated application domains:

- Activity Level Evaluation: Assessing findings given specific activity propositions, considering transfer and persistence factors [3].

- Multi-disciplinary Integration: Creating unified frameworks for interdisciplinary forensic evaluation, particularly between fiber evidence and forensic biology [3].

- Decision Support Systems: Developing tools that assist investigators and legal professionals in evaluating complex evidence constellations [8].

Current Research Frontiers

The field continues to evolve with several active research directions:

- Formal Property Verification: Establishing mathematical proofs for formal properties of inference systems and identifying assumptions for automated graph construction [10].

- Simplified Methodologies: Developing more accessible BN construction approaches to increase adoption among forensic practitioners [3].

- Complex Case Applications: Extending Bayesian methodologies to address increasingly complex forensic scenarios, including the evaluation of healthcare-related incidents [8].

The methodological transition from Wigmore Charts to modern Bayesian frameworks represents significant progress in addressing evidence uncertainty in forensic science. This evolution has maintained the intuitive narrative structure essential for legal communication while incorporating the mathematical rigor necessary for quantitative reasoning. Contemporary research continues to refine these hybrid approaches, enhancing their accessibility while maintaining analytical precision. The ongoing development of template models, simplified construction methodologies, and interdisciplinary integration points toward increasingly sophisticated applications of Bayesian reasoning across diverse forensic contexts, promising more robust and transparent evaluation of evidence in both legal and research settings.

Bayesian reasoning provides a formal probabilistic framework for updating beliefs in the presence of uncertainty. This paradigm aligns naturally with scientific and diagnostic processes, where initial hypotheses are refined as new data becomes available [11]. The core mechanism for this updating is Bayes' Theorem, which separates prior knowledge from the weight of new evidence, the latter often quantified through a likelihood ratio [12].

In forensic science, there is a growing movement to adopt quantitative methods, particularly likelihood ratios, for conveying the weight of evidence to legal decision-makers [12]. This whitepaper explores the foundational principles of Bayes' Theorem and likelihood ratios, detailing their calculation, application, and critical assessment within the context of forensic evidence uncertainty research.

Foundational Concepts and Theorem

Bayes' Theorem Formulation

Bayes' Theorem, at its core, describes the mathematical relationship between the prior probability of a hypothesis and its posterior probability after considering new evidence. The theorem is expressed as follows [11]:

P(A | B) = [P(B | A) × P(A)] / P(B)

In this formula:

P(A | B)is the posterior probability—the probability of hypothesisAgiven that evidenceBhas occurred.P(B | A)is the likelihood—the probability of observing evidenceBgiven that hypothesisAis true.P(A)is the prior probability—the initial degree of belief inAbefore considering evidenceB.P(B)is the marginal probability—the total probability of evidenceBunder all possible hypotheses.

For scientific inference, where multiple competing hypotheses are evaluated, the theorem is often used in its odds form. This form directly incorporates the likelihood ratio, providing a more intuitive framework for comparing hypotheses [12]:

Posterior Odds = Prior Odds × Likelihood Ratio

Core Components and Their Interpretation

Table 1: Core Components of Bayes' Theorem in Diagnostic and Forensic Contexts

| Component | Diagnostic Context (e.g., Medical Test) | Forensic Context (e.g., Evidence Evaluation) | Statistical Definition | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Prior Probability (P(A)) |

Disease prevalence in the population. | Initial belief in a proposition (e.g., defendant's guilt) based on other case information. | Degree of belief in a hypothesis before new data is observed. | |

| Likelihood (`P(B | A)`) | Test sensitivity (probability of a positive test given the disease is present). | Probability of observing the forensic evidence (e.g., DNA match) given the prosecution's proposition is true. | Probability of the data under a specific hypothesis. |

Marginal Probability (P(B)) |

Overall probability of a positive test result in the population. | Overall probability of observing the evidence under all considered propositions. | Total probability of the data, averaged over all hypotheses. | |

| Posterior Probability (`P(A | B)`) | Positive Predictive Value (probability of disease given a positive test). | Updated belief in the proposition after considering the forensic evidence. | Degree of belief in a hypothesis after considering the new data. |

The Likelihood Ratio as Weight of Evidence

Definition and Calculation

The Likelihood Ratio (LR) is a central measure of the strength of forensic evidence. It quantifies how much more likely the evidence is under one proposition compared to an alternative proposition [12]. The LR is calculated as follows:

LR = P(E | H_p) / P(E | H_d)

Where:

P(E | H_p)is the probability of the evidenceEgiven the prosecution's propositionH_p.P(E | H_d)is the probability of the evidenceEgiven the defense's propositionH_d.

The LR provides a balanced view of the evidence by considering its probability under at least two competing hypotheses, which aligns with the fundamental principles of forensic interpretation [13].

Principles for Forensic Interpretation

The application of likelihood ratios in forensic science should be guided by three core principles to minimize bias and ensure logical consistency [13]:

- Principle #1: Always consider at least one alternative hypothesis. Evidence cannot be interpreted in a vacuum; its meaning arises only from comparison.

- Principle #2: Always consider the probability of the evidence given the proposition and not the probability of the proposition given the evidence. This avoids the "prosecutor's fallacy," which mistakenly equates

P(E|H)withP(H|E). - Principle #3: Always consider the framework of circumstance. The interpretation of the evidence is always dependent on the specific context of the case.

The numerical value of the LR can be translated into a verbal scale to help communicate the strength of the evidence to legal decision-makers. There is no single standardized scale, but they generally follow a structure where values greater than 1 support the prosecution's proposition and values less than 1 support the defense's proposition.

Table 2: Likelihood Ratio Values and Their Corresponding Evidential Strength

| Likelihood Ratio Value | Verbal Equivalent | Support for Proposition |

|---|---|---|

| > 10,000 | Very strong support for H_p | Strongly supports the prosecution's proposition. |

| 1,000 to 10,000 | Strong support for H_p | |

| 100 to 1,000 | Moderately strong support for H_p | |

| 10 to 100 | Moderate support for H_p | |

| 1 to 10 | Limited support for H_p | |

| 1 | Inconclusive | The evidence is equally likely under both propositions; it offers no support to either side. |

| 0.1 to 1 | Limited support for H_d | |

| 0.01 to 0.1 | Moderate support for H_d | |

| 0.001 to 0.01 | Moderately strong support for H_d | |

| 0.0001 to 0.001 | Strong support for H_d | |

| < 0.0001 | Very strong support for H_d | Strongly supports the defense's proposition. |

Uncertainty and the Assumptions Lattice

The Subjectivity of the Likelihood Ratio

A critical examination reveals that a calculated LR is not a purely objective measure. Its value is contingent upon the model and the assumptions used to estimate the probabilities P(E | H_p) and P(E | H_d) [12]. These assumptions can include choices about the relevant population, the statistical model form, and the parameter values. Therefore, a single LR value provided by an expert cannot be considered the definitive "weight of evidence," as it represents only one realization based on a specific set of assumptions.

The Uncertainty Pyramid Framework

To properly assess the fitness of a reported LR, it is necessary to characterize its uncertainty. The assumptions lattice and uncertainty pyramid framework provide a structured way to analyze this [12].

- Assumptions Lattice: This is a hierarchical structure of the assumptions made during the evaluation of the LR. At the base of the lattice are many conservative and simplistic assumptions. As one moves up the lattice, assumptions become more refined and realistic, but also more complex and potentially more reliant on subjective choices.

- Uncertainty Pyramid: This concept visualizes how the range of possible LR values changes across different levels of the assumptions lattice. At the pyramid's base (the lattice's simple assumptions), the LR might be estimated with low uncertainty but may be a poor representation of reality. As one moves up the pyramid (using more complex models in the lattice), the potential range of plausible LR values may widen, reflecting the increased uncertainty from modeling choices.

This framework emphasizes that reporting an LR without an accompanying uncertainty assessment can be misleading. It encourages experts to explore the sensitivity of the LR to different reasonable assumptions and to communicate this to the fact-finder.

Diagram 1: The Uncertainty Pyramid of Model Assumptions. As models become more complex and realistic, the uncertainty in the resulting Likelihood Ratio often increases.

Experimental and Methodological Protocols

Protocol for LR Calculation in Forensic Evidence Evaluation

This protocol provides a general framework for calculating a likelihood ratio in a forensic context, such as for a glass fragment or fingerprint evidence [12].

- Case Context Review: Acquire all relevant case information to define the appropriate propositions and relevant population.

- Define Propositions: Formulate at least two mutually exclusive propositions (e.g.,

H_p: The glass fragment originated from the crime scene window;H_d: The glass fragment originated from some other, unknown source). - Data Collection:

- Control Data: Collect measurements from a known source related to

H_p(e.g., refractive index of the crime scene glass). - Background Data: Obtain a representative sample of measurements from the relevant population defined by

H_d(e.g., refractive indices of glass from a database of auto windows).

- Control Data: Collect measurements from a known source related to

- Model Selection: Choose a statistical model (e.g., a Normal distribution for continuous data like refractive index) to describe the data under each proposition.

- Probability Calculation:

- Calculate

P(E | H_p): The probability density of the observed evidence (e.g., the measured RI of the suspect fragment) given the model fitted to the control data. - Calculate

P(E | H_d): The probability density of the observed evidence given the model fitted to the background data.

- Calculate

- LR Computation: Compute the ratio

LR = P(E | H_p) / P(E | H_d). - Uncertainty and Sensitivity Analysis: Assess the robustness of the LR by varying key assumptions (e.g., the choice of background population, the statistical model) to understand the range of plausible LR values.

Protocol for Bayesian Experimental Design

Bayesian experimental design uses probability theory to maximize the expected information gain from an experiment before it is conducted [14]. The following protocol is applicable to fields like clinical trial design.

- Define Utility: Specify a utility function

U(ξ)that quantifies the goal of the experiment for a given designξ. A common choice is the expected gain in Shannon information or the Kullback-Leibler divergence between the prior and posterior distributions [14]. - Specify Prior: Elicit a prior probability distribution

p(θ)for the parametersθof interest, based on existing knowledge. - Define Model: Formulate a probabilistic model

p(y | θ, ξ)for the dataythat would be observed for a given designξand parametersθ. - Compute Posterior: Use Bayes' Theorem to derive the form of the posterior distribution

p(θ | y, ξ). - Calculate Expected Utility: For each candidate experimental design

ξ, compute the expected utility by integrating over all possible data outcomes and parameter values:U(ξ) = ∫∫ U(y, ξ) p(y, θ | ξ) dy dθ. - Optimize Design: Select the experimental design

ξ*that maximizes the expected utilityU(ξ).

Diagram 2: Workflow for Bayesian Optimal Experimental Design. The process iterates to find the design that maximizes the expected information gain.

Visualization and Signaling Pathways

The process of updating beliefs with new evidence via Bayes' Theorem can be visualized as a fundamental signaling pathway in logical reasoning.

Diagram 3: The Bayesian Reasoning Signaling Pathway. This shows the core logic of how prior beliefs are updated with new evidence to form a posterior belief, which then informs the next prior.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section details key methodological components and "reagents" essential for conducting research and analysis involving Bayes' Theorem and Likelihood Ratios.

Table 3: Essential Methodological Reagents for Bayesian and LR-Based Research

| Research Reagent | Function and Role in Analysis | Example Applications | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Probabilistic Graphical Models | A framework for representing complex conditional dependencies between variables in a system. Facilitates the structuring of hypotheses and evidence. | Building complex forensic inference networks; modeling disease pathways in drug discovery [15]. | |

| Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) Samplers | Computational algorithms for drawing samples from complex posterior probability distributions that cannot be derived analytically. | Parameter estimation in complex models for calculating `P(E | H)`; Bayesian experimental design [14]. |

| Informative Prior Distributions | Probability distributions that incorporate existing knowledge or beliefs about a parameter before the current data is observed. | Incorporating historical data or expert elicitation into clinical trial analysis [11]. | |

| High-Quality Reference Databases | Curated, population-representative datasets used to estimate the probability of evidence under alternative propositions H_d. |

Estimating the rarity of a DNA profile or the chemical composition of a drug exhibit in a forensic population. | |

| Utility Functions for Decision Theory | Mathematical functions that quantify the cost or benefit of different experimental outcomes and decisions. | Optimizing clinical trial design to maximize information gain or minimize patient harm [14]. | |

| Sensitivity Analysis Protocols | A planned set of procedures to test how sensitive a result (e.g., an LR) is to changes in underlying assumptions or model parameters. | Assessing the robustness of forensic conclusions; validating Bayesian models [12]. |

Forensic science stands at a critical juncture, navigating a fundamental transition from traditional methodologies reliant on human perception and subjective judgment toward a new paradigm grounded in quantitative measurements, statistical modeling, and empirical validation. This shift is driven by mounting recognition of the limitations inherent in conventional forensic practices, which often depend on unarticulated standards and lack statistical foundation for error rate estimation [16]. The 2009 National Academy of Sciences report starkly highlighted these concerns, noting that much forensic evidence enters criminal trials "without any meaningful scientific validation, determination of error rates, or reliability testing" [16]. In response, a revolutionary framework is emerging—one that replaces subjective judgment with methods based on relevant data, quantitative measurements, and statistical models that are transparent, reproducible, and intrinsically resistant to cognitive bias [17]. This transformation is particularly crucial when framed within Bayesian reasoning for forensic evidence uncertainty research, as it provides the logical framework for interpreting evidence through likelihood ratios and enables rigorous quantification of uncertainty in forensic conclusions. The integration of Bayesian principles addresses the core challenge of accurately updating prior beliefs with new forensic evidence, moving the field toward more scientifically defensible practices that can withstand legal and scientific scrutiny.

Operational Challenges in Traditional Forensic Methods

Subjectivity and Cognitive Bias in Pattern Evidence

The operational landscape of traditional forensic science is riddled with challenges stemming from its reliance on human interpretation of pattern evidence. Current forensic practice for fracture matching typically involves visual inspection of complex jagged trajectories to recognize matches through comparative microscopy and tactile pattern analysis [16]. This process correlates macro-features on fracture fragments but remains inherently subjective, as the microscopic details of non-contiguous crack edges cannot always be directly linked to a pair of fracture surfaces except by highly experienced examiners [16]. The central problem lies in what the NAS report characterized as "subjective decision based on unarticulated standards and no statistical foundation for estimation of error rates" [16]. This subjectivity creates vulnerability to cognitive biases, which Bayesian frameworks recast as maladaptive probability weighting in specific contexts [18]. For instance, base-rate neglect—the tendency to underweight prior probabilities when evaluating novel evidence—often emerges in realistic large-world scenarios where convincing eyewitness evidence overshadows statistical base rates [18]. Similarly, conservatism bias manifests when individuals inadequately update prior beliefs in response to additional evidence, particularly in abstract small-world tasks where prior probabilities become highly salient [18]. These biases directly impact forensic decision-making, particularly when experts are presented with contextual information that may influence their interpretation of physical evidence.

Technological Limitations and Scale Considerations

Forensic analysis faces significant technological limitations related to imaging scale and resolution. When comparing characteristic features on fractured surfaces, identifying the proper magnification and field of view becomes critical [16]. At high magnification with small fields of view, optical images possess visually indistinguishable characteristics where surface roughness shows self-affine or fractal nature [16]. Conversely, employing lower magnifications reduces the power to identify class characteristics of surfaces [16]. Research has revealed that the transition scale of the height-height correlation function captures the uniqueness of fracture surfaces, occurring at approximately 2–3 times the average grain size for materials undergoing cleavage fracture (typically 50–75 μm for tested material systems) [16]. This scale corresponds to the average cleavage critical distance for local stresses to reach critical fracture stress required for cleavage initiation [16]. The stochastic nature of this critical microstructural size scale necessitates imaging at appropriate resolutions to capture forensically relevant details, yet this is often complicated by practical constraints in field deployment of analytical technologies and the balance between resolution and field of view.

Table 1: Key Challenges in Traditional Forensic Pattern Analysis

| Challenge Category | Specific Limitations | Impact on Forensic Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Human Interpretation | Subjective pattern recognition without statistical foundation | Non-transparent conclusions susceptible to cognitive bias |

| Technological Constraints | Improper imaging scale and resolution | Failure to capture unique surface characteristics at relevant length scales |

| Statistical Framework | Lack of error rate quantification and validation | Difficulty establishing scientific reliability for legal proceedings |

| Context Dependence | Variable performance across different scenario types | Inconsistent application and interpretation of evidence |

Structural Barriers to Implementing Quantitative Frameworks

Systemic and Institutional Hurdles

The implementation of quantitative frameworks in forensic science faces profound structural barriers that hinder global adoption. Evaluative reporting using activity-level propositions addresses how and when questions about forensic evidence presence—often the exact questions of interest to legal fact-finders [19]. Despite its importance, widespread adoption has been hampered by multiple factors: reticence toward suggested methodologies, concerns about lack of robust and impartial data to inform probabilities, regional differences in regulatory frameworks and methodology, and variable availability of training and resources to implement evaluations given activity-level propositions [19]. The forensic community across different jurisdictions exhibits varying levels of resistance to proposed methodologies, often stemming from deeply entrenched practices and cultural norms within forensic institutions. Additionally, the absence of standardized protocols for data generation and sharing impedes the development of the statistical databases necessary for robust probabilistic interpretation of evidence. These structural barriers create a significant gap between research advancements and practical implementation, leaving many forensic laboratories operating with outdated methodologies despite the demonstrated potential of quantitative approaches.

Resource and Training Deficiencies

The transition to quantitative forensic methodologies requires substantial investment in both instrumentation and expertise, creating significant resource-related barriers. Advanced analytical techniques such as liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) and comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography coupled with time-of-flight mass spectrometry (GC×GC–TOF-MS) offer transformative potential for forensic analysis but require substantial financial resources, technical infrastructure, and specialized operator training [20] [21]. The expertise gap is particularly pronounced, as effective implementation of Bayesian frameworks and statistical learning approaches requires interdisciplinary knowledge spanning forensic science, statistics, and specific analytical domains. This challenge is especially acute for resource-constrained agencies, potentially creating disparities in forensic capabilities across jurisdictions [19]. The availability of training in quantitative methods remains inconsistent, and existing educational programs often emphasize traditional pattern-matching approaches over statistical interpretation. Furthermore, the forensic community lacks standardized competency frameworks for quantitative methodologies, making it difficult to ensure consistent application and interpretation across different practitioners and laboratories.

Quantitative Approaches and Bayesian Solutions

Statistical Learning for Fracture Surface Matching

A groundbreaking quantitative approach to fracture matching utilizes spectral analysis of surface topography mapped by three-dimensional microscopy combined with multivariate statistical learning tools [16]. This methodology leverages the unique transition scale of fracture surface topography, where the statistics of the fracture surface become non-self-affine, typically at approximately 2–3 grains for cleavage fracture [16]. The framework employs height-height correlation functions to quantify surface roughness and identify the characteristic scale at which surface uniqueness emerges, then applies statistical classification to distinguish matching and non-matching specimens with near-perfect accuracy [16]. The analytical process involves measuring the height-height correlation function δh(δx)=√⟨[h(x+δx)-h(x)]²⟩ₓ, where the ⟨⋯⟩ operator denotes averaging over the x-direction [16]. This function reveals the self-affine nature of fracture surfaces at small length scales (less than 10–20 μm) while demonstrating deviation and saturation at larger length scales (>50–70 μm) that captures surface individuality [16]. The imaging scale for comparison must be greater than approximately 10 times the self-affine transition scale to prevent signal aliasing, ensuring capture of forensically discriminative features [16].

Figure 1: Quantitative Fracture Surface Analysis Workflow

Bayesian Framework for Evidence Interpretation

The likelihood ratio framework represents the logically correct approach for evidence interpretation within Bayesian reasoning, providing a coherent structure for updating prior beliefs based on forensic findings [17]. This framework quantitatively expresses the probative value of evidence by comparing the probability of the evidence under two competing propositions—typically the prosecution and defense hypotheses [17]. The Bayesian approach properly contextualizes forensic findings within case circumstances and population data, directly addressing the uncertainty inherent in forensic evidence. The fundamental theorem can be expressed as:

[ \text{Posterior Odds} = \text{Likelihood Ratio} \times \text{Prior Odds} ]

Where the Likelihood Ratio ( LR = \frac{P(E|Hp)}{P(E|Hd)} ) represents the probability of the evidence E given the prosecution proposition ( Hp ) divided by the probability of the evidence given the defense proposition ( Hd ) [17]. This framework explicitly separates the role of the forensic expert (providing the LR) from the role of the court (assessing prior odds and determining posterior odds), maintaining appropriate boundaries while providing a transparent, quantitative measure of evidentiary strength. The Bayesian approach naturally handles uncertainty and avoids the logical fallacies common in traditional forensic testimony, such as the prosecutor's fallacy that mistakenly transposes conditional probabilities.

Table 2: Bayesian Framework Applications in Forensic Evidence

| Forensic Discipline | Quantitative Measurement Approach | Likelihood Ratio Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Fracture Surface Matching | Spectral topography analysis with statistical learning | Classification probabilities converted to LRs for match/non-match |

| Fingerprint Analysis | Minutiae marking and scoring based on match | Probabilistic model reporting LR for correspondence [16] |

| Ballistics Identification | Congruent Matching Cells approach dividing surfaces | Statistical model outputting LR for cartridge case matching [16] |

| Drug Analogs Characterization | LC–ESI–MS/MS fragmentation profiling | Diagnostic product ions distinction for analog identification [20] |

Experimental Protocols for Advanced Forensic Analysis

Protocol: Fracture Surface Topography and Statistical Matching

Objective: To quantitatively match forensic evidence fragments using fracture surface topography and statistical learning for objective forensic comparison [16].

Materials and Equipment:

- Fractured evidence specimens (metal, glass, or other brittle materials)

- Three-dimensional surface microscope (confocal or interferometric)

- Computational software for spectral analysis (MATLAB, R, or Python with appropriate packages)

- Statistical learning environment (R with MixMatrix package or equivalent) [16]

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Mount fracture fragments to ensure stable imaging without surface contamination. Clean surfaces with appropriate solvents to remove debris while preserving topographic features.

- 3D Topographical Imaging: Acquire surface topography data using 3D microscopy at appropriate scale. Set field of view greater than 10 times the self-affine transition scale (typically >500-700 μm for metallic materials) with resolution sufficient to capture micro-topographic details.

- Height-Height Correlation Analysis: Compute the height-height correlation function δh(δx)=√⟨[h(x+δx)-h(x)]²⟩ₓ across the surface. Identify the transition length scale where the correlation function deviates from self-affine behavior and saturates.

- Spectral Feature Extraction: Perform spectral analysis of surface topography at multiple frequency bands around the identified transition scale. Extract multivariate descriptors capturing surface uniqueness.

- Statistical Model Training: Utilize training datasets of known matching and non-matching surfaces to develop classification models. Apply multivariate statistical learning tools (e.g., linear discriminant analysis, support vector machines) to distinguish surface pairs.

- Likelihood Ratio Calculation: Convert classification results to likelihood ratios using the statistical model. Establish decision thresholds based on empirical validation studies to report "match" or "non-match" conclusions with estimated error rates.

Validation: Perform cross-validation studies to estimate classification error rates and model performance across different materials and fracture modes.

Protocol: Chromatographic Analysis for Forensic Chemistry

Objective: To characterize novel nitazene analogs and estimate fingerprint age using advanced chromatographic techniques [20].

Materials and Equipment:

- Liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry (LC–ESI–MS/MS) system

- Comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography coupled with time-of-flight mass spectrometry (GC×GC–TOF-MS)

- Reference standards of target compounds

- Chemometric software for data analysis and modeling

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Extract analytes from forensic specimens using appropriate techniques (SALLE for stimulants, SPME for volatile compounds) [20].

- Instrumental Analysis:

- For nitazene analogs: Perform LC–ESI–MS/MS analysis with fragmentation profiling to characterize 38 nitazene analogs and establish diagnostic product ions for identification [20].

- For fingerprint aging: Conduct GC×GC–TOF-MS analysis to detect time-dependent chemical changes in fingerprints, enabling age estimation through chemometric modeling [20].

- Data Processing: Apply unsupervised pattern recognition to identify characteristic chemical profiles. Develop multivariate models correlating chemical signatures with evidence attributes (e.g., time since deposition).

- Statistical Interpretation: Construct likelihood ratios based on chemical similarity metrics to evaluate evidence propositions quantitatively.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Analytical Tools for Quantitative Forensics

| Tool/Reagent | Technical Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| 3D Surface Microscope | High-resolution topographical mapping of fracture surfaces | Quantitative analysis of fracture surface topography for matching [16] |

| LC–ESI–MS/MS System | High-sensitivity identification and characterization of compounds | Forensic toxicology, drug analog identification, and metabolite detection [20] [21] |

| GC×GC–TOF-MS | Comprehensive separation and detection of complex mixtures | Fingerprint age estimation, VOC profiling, and chemical signature analysis [20] |

| Statistical Learning Software | Multivariate classification and likelihood ratio calculation | Pattern recognition, evidence evaluation, and error rate estimation [16] |

| Reference Material Databases | Population data for statistical modeling and comparison | Informing prior probabilities and reference distributions for Bayesian analysis [17] |

Forensic science stands at a pivotal moment where operational and structural challenges demand fundamental transformation toward quantitative, Bayesian frameworks. The integration of statistical learning approaches with advanced analytical technologies offers a pathway to overcome subjectivity, cognitive bias, and the lack of statistical foundation that have long plagued traditional forensic methods. The quantitative matching of fracture surfaces using topography analysis and statistical classification demonstrates the powerful potential of these approaches, achieving near-perfect discrimination between matching and non-matching specimens while providing measurable error rates and transparent methodology [16]. Similarly, advanced chromatographic techniques coupled with chemometric modeling enable forensic chemists to extract temporal and identificatory information previously inaccessible through conventional methods [20]. The structural barriers to implementation—including institutional resistance, resource limitations, and training deficiencies—remain significant but not insurmountable. By embracing the paradigm shift toward data-driven, statistically validated methods grounded in Bayesian reasoning, the forensic science community can navigate this critical juncture to establish more rigorous, reliable, and scientifically defensible practices. This transformation is essential not only for advancing forensic science as a discipline but also for ensuring the integrity of criminal justice outcomes through scientifically valid evidence evaluation.

This technical guide examines the profound epistemological divide between laboratory science and legal proceedings, focusing on the evaluation of forensic evidence. In laboratory settings, scientific conclusions are inherently probabilistic and continuously updated through a Bayesian framework, which quantifies uncertainty and incorporates new data. In contrast, courtroom settings often seek binary truths—guilty or not guilty—through an adversarial process constrained by constitutional protections such as the Confrontation Clause. This whitepaper explores this divergence through the lens of Bayesian reasoning, detailing methodologies for modeling forensic evidence under activity-level propositions and analyzing how legally imposed procedures shape the admission and interpretation of scientific data. Designed for researchers, forensic scientists, and legal professionals, it provides structured data, experimental protocols, and visual workflows to bridge these two distinct domains of knowledge.

The fundamental disconnect between scientific and legal processes for establishing "truth" presents significant challenges for the use of forensic evidence in criminal justice. Scientific truth is probabilistic, iterative, and quantified, whereas legal truth is procedural, binary, and final. This epistemological divide is particularly evident in the application of forensic science, where evidence must transition from the laboratory bench to the courtroom.

- Scientific Truth: In laboratory science, knowledge advances through Bayesian updating, where prior beliefs are systematically updated with new empirical data to form posterior probabilities. This process embraces uncertainty as an inherent aspect of scientific reasoning [3] [22]. For instance, a Bayesian network can model the probability of finding specific fiber evidence given different activity scenarios, providing a transparent framework for expressing the strength of evidence [3].

- Legal Truth: In courtroom proceedings, truth is established through adversarial testing and is bound by strict constitutional and evidentiary rules. The recent Supreme Court ruling in Smith v. Arizona reinforced that the Confrontation Clause requires forensic analysts who performed testing to be available for cross-examination, preventing the use of substitute experts as mere "mouthpieces" for absent analysts [23] [24]. This legal process seeks a definitive outcome, often forcing continuous scientific probabilities into discrete legal categories.

This guide operationalizes these concepts by framing forensic evidence evaluation within a Bayesian paradigm, detailing its methodologies, and analyzing the legal constraints that govern its admission in court.

Bayesian Reasoning in Forensic Science

Bayesian methods provide a coherent mathematical framework for updating beliefs in light of new evidence. This is formally expressed through Bayes' Theorem, which calculates a posterior probability based on prior knowledge and new data.

Foundational Principles and Theorem

The theorem is formally expressed as:

P(H|E) = [P(E|H) × P(H)] / P(E)

Where:

- P(H|E) is the posterior probability of the hypothesis given the evidence.

- P(E|H) is the likelihood of observing the evidence if the hypothesis is true.

- P(H) is the prior probability of the hypothesis.

- P(E) is the probability of the evidence.

In forensic contexts, this framework is used to evaluate the Likelihood Ratio (LR), which assesses the probability of the evidence under two competing propositions (e.g., prosecution and defense hypotheses) [3].

Quantitative Bayesian Applications in Forensic Analysis

Table 1: Bayesian Applications in Forensic and Reliability Sciences

| Application Domain | Quantitative Metric | Methodological Approach | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forensic Fibre Evidence [3] | Likelihood Ratio (LR) for activity-level propositions | Construction of narrative Bayesian Networks (BNs) from case scenarios | BNs provide a transparent, accessible structure for evaluating complex, case-specific fibre transfer findings. |

| Human Reliability Analysis [25] | Human Error Probability (HEP) | Ensemble model as weighted average of HRA method predictions; weights updated via Bayesian scheme | Beliefs in HRA methods are quantitatively updated; methods with better predictive capability receive higher weights. |

| Psychological Measurement [22] | Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) | Bayesian testing of homogeneous vs. heterogeneous within-person variance | Individuals exhibit significant variation in reliability (ICC); common variance assumption often masks tenfold differences in person-specific reliability. |

Advanced Bayesian Modeling Techniques

Advanced implementations extend these basic principles. For instance, an ensemble model for Human Reliability Analysis (HRA) can be constructed as a weighted average of predictions from various constituent methods: f(p|S) = Σ [P(M_i) * f_i(p|S)], where P(M_i) represents the prior belief in method M_i [25]. These weights are updated based on performance against empirical human performance data, increasing the influence of more predictive methods and decreasing that of less accurate ones [25].

Similarly, Bayesian testing of heterogeneous variance allows researchers to move beyond the assumption of a common within-person variance, which is often violated. Using Bayes factors, one can test for individually varying ICCs, revealing that reliability is not a stable property of a test but can vary dramatically between individuals [22].

Experimental Protocols for Bayesian Forensic Evaluation

This section provides a detailed methodology for constructing and applying Bayesian Networks to the evaluation of forensic fibre evidence, aligning with the narrative approach recommended for interdisciplinary collaboration [3].

Protocol: Constructing a Narrative Bayesian Network

Objective: To develop a Bayesian Network for evaluating forensic fibre findings given activity-level propositions, incorporating case circumstances and enabling sensitivity analysis.

Materials:

- Case data (e.g., fibre transfer evidence, suspect and victim clothing information, activity scenario descriptions).

- Computational environment for BN construction and probability calculation (e.g., specialized BN software, R or Python with relevant libraries).

Procedure:

- Define Propositions: Formulate mutually exclusive activity-level propositions (e.g., "The suspect performed the alleged activity" vs. "The suspect had no contact with the scene").

- Identify Relevant Factors: List all case circumstances and factors that influence the probability of the evidence. This includes:

- Transfer Persistence: The probability of fibre transfer and persistence given the alleged activity.

- Background Presence: The probability of finding matching fibres by chance on the suspect's clothing.

- Evidence Recovery: The efficiency of the evidence collection and analysis techniques.

- Structure the Network: Construct a directed acyclic graph (DAG) where:

- Parent nodes represent the activity-level propositions and foundational factors (e.g., "Primary Transfer," "Background Presence").

- Child nodes represent observable outcomes (e.g., "Fibre Match Found").

- Conditional dependencies are represented by arrows, mapping the influence between nodes.

- Parameterize the Model: Populate the network with conditional probability tables (CPTs) for each node. These probabilities are initially based on empirical data, expert judgment, or relevant literature.

- Enter Evidence and Calculate: Instantiate the network with the specific evidence observed in the case (e.g., set the "Fibre Match Found" node to "True"). Calculate the updated posterior probabilities for the activity-level propositions.

- Conduct Sensitivity Analysis: Systematically vary the probabilities in key nodes (e.g., transfer probabilities) to assess the robustness of the network's output and identify critical assumptions.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for the construction and application of a narrative Bayesian Network in forensic evaluation.

The Legal Framework: Constraining Scientific Evidence

The transition of forensic evidence from the laboratory to the courtroom is governed by legal rules that can conflict with scientific reasoning. The Confrontation Clause of the Sixth Amendment is a primary example, recently clarified in Smith v. Arizona [23] [24].

The Confrontation Clause and Forensic Reports

The Supreme Court held that when a substitute expert witness presents the out-of-court statements of a non-testifying analyst as the basis for their own opinion, those statements are being offered for their truth, thus triggering Confrontation Clause protections [23]. The defendant has the right to cross-examine the analyst who performed the testing about their procedures, potential errors, and the results' integrity [23] [24].

- The "Mouthpiece" Prohibition: The Court rejected the notion that a substitute analyst can simply act as a conduit for the original analyst's report. Testimony that affirms the truth of the absent analyst's procedures and findings violates the defendant's rights [23].

- Permissible Expert Testimony: Experts are still permitted to testify about general laboratory procedures, industry standards, or to offer opinions based on hypothetical questions [23] [26]. The critical distinction is that the expert cannot merely relay the specific, testimonial findings of an absent colleague.

Machine-Generated Data versus Human Analysis

A developing frontier in confrontation law involves "purely machine-generated data." The North Carolina Supreme Court in State v. Lester held that automatically generated phone records are non-testimonial because they are "created entirely by a machine, without any help from humans" [26]. This logic was extended in dicta to include data from instruments like gas chromatograph/mass spectrometers [26].

However, this view is in tension with the U.S. Supreme Court's reasoning in Bullcoming v. New Mexico, which emphasized that a forensic report certifying proper sample handling, protocol adherence, and uncontaminated equipment involves "representations, relating to past events and human actions not revealed in raw, machine-produced data," making them subject to cross-examination [24] [26]. This creates a significant epistemological conflict: what a legal authority may classify as raw machine data, a scientific perspective recognizes as the output of a process dependent on human judgment and intervention at multiple steps.

Table 2: Legal Standards for the Admissibility of Forensic Evidence

| Evidence Type | Key Legal Precedent | Confrontation Clause Status | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Forensic Lab Report (e.g., drugs, DNA) | Melendez-Diaz v. Massachusetts [24], Smith v. Arizona [23] | Testimonial | The report is created for use in prosecution, and the analyst's statements about their actions and conclusions are accusatory. |

| Substitute Analyst Testimony | Smith v. Arizona [23], State v. Clark [26] | Violation if acting as a "mouthpiece" | A surrogate expert cannot be used to parrot the absent analyst's specific findings without the defendant having a chance to cross-examine the original analyst. |

| Purely Machine-Generated Data (e.g., phone records, seismograph readouts) | State v. Lester [26] | Non-Testimonial | Data is generated automatically by machine programming without human intervention or interpretation, lacking a "testimonial" purpose. |

| Expert Basis Testimony | Smith v. Arizona [23], Bullcoming v. New Mexico [24] | Permissible within limits | An expert can testify to their own independent opinion and explain the general basis for it, but cannot affirm the truth of an absent analyst's specific report. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and computational tools essential for conducting Bayesian reliability research and forensic evidence evaluation.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Bayesian Forensic and Reliability Analysis

| Item / Solution | Function / Application | Technical Specification / Notes |

|---|---|---|

Bayesian Network Software (e.g., specialized commercial suites, R bnlearn, Python pgmpy) |

Provides environment for constructing, parameterizing, and performing probabilistic inference on graphical models. | Essential for implementing the narrative BN methodology for activity-level evaluation of trace evidence [3]. |

| R Package `vICC | Implements Bayesian methodology for testing homogeneous versus heterogeneous within-person variance in hierarchical models. | Allows researchers to test for and quantify individually varying reliability (ICC), moving beyond the assumption of a common within-person variance [22]. |

| Human Performance Data (e.g., from simulator studies) | Serves as the empirical basis for updating prior beliefs in Bayesian models, such as the ensemble model for HRA methods. | Data quality is critical; the International HRA Empirical Study used a full-scope nuclear power plant simulator to collect operator performance data [25]. |

| Gas Chromatograph/Mass Spectrometer (GC/MS) | Provides chemical analysis of unknown substances; a key tool in forensic drug chemistry. | While the machine produces data, the sample preparation, instrument calibration, and interpretation of results involve critical human steps, making the overall process testimonial under Bullcoming [24] [26]. |

Integrated Analysis: A Bayesian-legal Workflow

The following diagram synthesizes the scientific and legal pathways for forensic evidence, from analysis to legal admission, highlighting critical decision points shaped by both Bayesian logic and constitutional law.

The epistemological divide between laboratory and courtroom settings necessitates a sophisticated approach to forensic evidence. Bayesian reasoning provides the necessary scientific framework for quantifying uncertainty and updating beliefs in a transparent, logically sound manner. However, this probabilistic scientific truth must navigate a legal system that demands categorical outcomes and is bounded by constitutional protections like the Confrontation Clause.

Bridging this divide requires mutual understanding: forensic scientists must articulate their findings in a way that acknowledges uncertainty and aligns with methodological transparency, while the legal system must develop a more nuanced appreciation for probabilistic evidence without compromising defendants' rights. The integration of narrative Bayesian Networks and strict adherence to the principles underscored in Smith v. Arizona represent a path forward. This allows for a more holistic and rigorous evaluation of forensic evidence, respecting both the scientific method and the foundational principles of a fair trial.

The admissibility of expert testimony is a cornerstone of modern litigation, particularly in complex cases involving scientific, technical, or other specialized knowledge. The evolution of admissibility standards from a laissez-faire approach to the structured frameworks of Frye and Daubert represents a fundamental shift in how courts assess the reliability of expert evidence. This evolution mirrors a broader judicial recognition of the potential for expert evidence to be both "powerful and quite misleading" if not properly scrutinized [27].

Within the context of Bayesian reasoning and forensic evidence uncertainty research, understanding these legal standards becomes paramount. Bayesian reasoning provides a mathematical framework for updating the probability of a hypothesis as new evidence is introduced, making the reliability and validity of that initial evidence critically important. The different admissibility standards directly impact which scientific methodologies and expert conclusions reach the fact-finder, thereby influencing the entire probabilistic chain of reasoning in forensic science and legal decision-making.

Historical Evolution of Admissibility Standards

The Laissez-Faire Era

Prior to the development of formal admissibility tests, courts exercised minimal control over the substance of expert testimony [28]. This era might well be characterized as a laissez-faire judicial regime, in which courts deferred to expert witnesses and juries without supervising the quality or sufficiency of underlying facts and data, or the validity of inferences [28].

- Basis for Admission: Under this approach, expert witnesses needed only to be qualified by training, education, or experience, and their opinions needed to be relevant to the issues in the case [28].

- Role of the Court: The court's role was largely passive. Once a witness was shown to be qualified, the fact-finder (usually a jury) was free to accept or reject the expert's testimony without judicial guidance on its scientific validity [28].

- Limitations: This approach has been criticized as an "authoritarian standard," under which the possession of credentials entitled the bearer to hold forth as an expert witness at trial, with no obligation to comply with the ethical or substantive requirements of their discipline [28].

The Frye Standard and the "General Acceptance" Test

In 1923, the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit established a new standard in Frye v. United States, a case involving the admissibility of polygraph evidence [29] [30]. The court articulated what would become known as the "general acceptance" test:

"Just when a scientific principle or discovery crosses the line between the experimental and demonstrable stages is difficult to define. Somewhere in this twilight zone the evidential force of the principle must be recognized, and while courts will go a long way in admitting expert testimony deduced from a well-recognized scientific principle or discovery, the thing from which the deduction is made must be sufficiently established to have gained general acceptance in the particular field in which it belongs." [31] [30]

- Judicial Application: For a scientific technique or principle, a court applying the Frye standard must determine whether the method is generally accepted by experts in the relevant field [29]. The inquiry is focused on the methodology itself, not the correctness of the expert's conclusions [31].

- Scope and Limitations: The Frye standard was praised for helping to keep pseudoscience out of the courtroom but was also criticized for being too conservative and potentially excluding reliable but novel science that had not yet gained widespread acceptance [29] [32].

The Daubert Trilogy and the Rise of Judicial Gatekeeping