Atomic Spectroscopy Techniques for Elemental Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Drug Development Professionals

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of major atomic spectroscopy techniques—including AAS, ICP-OES, and ICP-MS—for elemental analysis.

Atomic Spectroscopy Techniques for Elemental Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Drug Development Professionals

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of major atomic spectroscopy techniques—including AAS, ICP-OES, and ICP-MS—for elemental analysis. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers foundational principles, methodological applications, troubleshooting for complex samples, and a data-driven comparative analysis. The guide synthesizes performance metrics, cost considerations, and regulatory compliance to empower informed technique selection for pharmaceutical quality control, environmental monitoring, and materials characterization.

Core Principles of Atomic Spectroscopy: Understanding the Fundamentals of Elemental Analysis

Atomic spectrometry techniques are foundational tools for elemental analysis, enabling the detection and quantification of metal concentrations in diverse samples from environmental, biological, and industrial matrices. Among the most prominent techniques are Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS), Atomic Emission Spectroscopy (AES), and Inductively Coupled Plasma (ICP)-based methods. Each technique operates on distinct principles—measuring the absorption of light, the emission of light from excited atoms, or utilizing a high-temperature plasma for excitation and ionization. Understanding their fundamental differences, performance characteristics, and optimal applications is crucial for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to implement precise and efficient analytical protocols. This guide provides a comparative overview of these techniques, supported by experimental data and procedural details, to inform method selection for elemental analysis research.

Core Principles and Instrumentation

Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS)

Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS) is a technique that measures the concentration of specific elements by analyzing the absorption of light by free atoms in the gaseous state [1] [2]. The sample is vaporized in a flame or graphite furnace atomizer, and a light source (hollow cathode lamp) emits element-specific wavelengths. The amount of light absorbed at a characteristic wavelength is proportional to the concentration of the element in the sample [1].

Atomic Emission Spectroscopy (AES)

Atomic Emission Spectroscopy (AES) measures the intensity of light emitted by excited atoms as they return to the ground state [1]. The sample is introduced into an excitation source, such as a flame or plasma. The high temperature of the source excites the atoms, and as they relax, they emit light at wavelengths characteristic of each element. The intensity of this emitted light is used for quantitative analysis [1].

Inductively Coupled Plasma (ICP) Techniques

Inductively Coupled Plasma (ICP) spectroscopy uses a high-temperature plasma source (typically 6,000-10,000 K) sustained by a radiofrequency (RF) generator to both atomize and excite sample elements [1] [3]. There are two primary variants:

- ICP-Optical Emission Spectroscopy (ICP-OES): Also known as ICP-Atomic Emission Spectroscopy (ICP-AES), this technique measures the intensity of light emitted by excited atoms at specific wavelengths [3] [2].

- ICP-Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS): This technique ionizes the sample in the plasma and then separates and detects ions based on their mass-to-charge ratio, offering ultra-low detection limits [2].

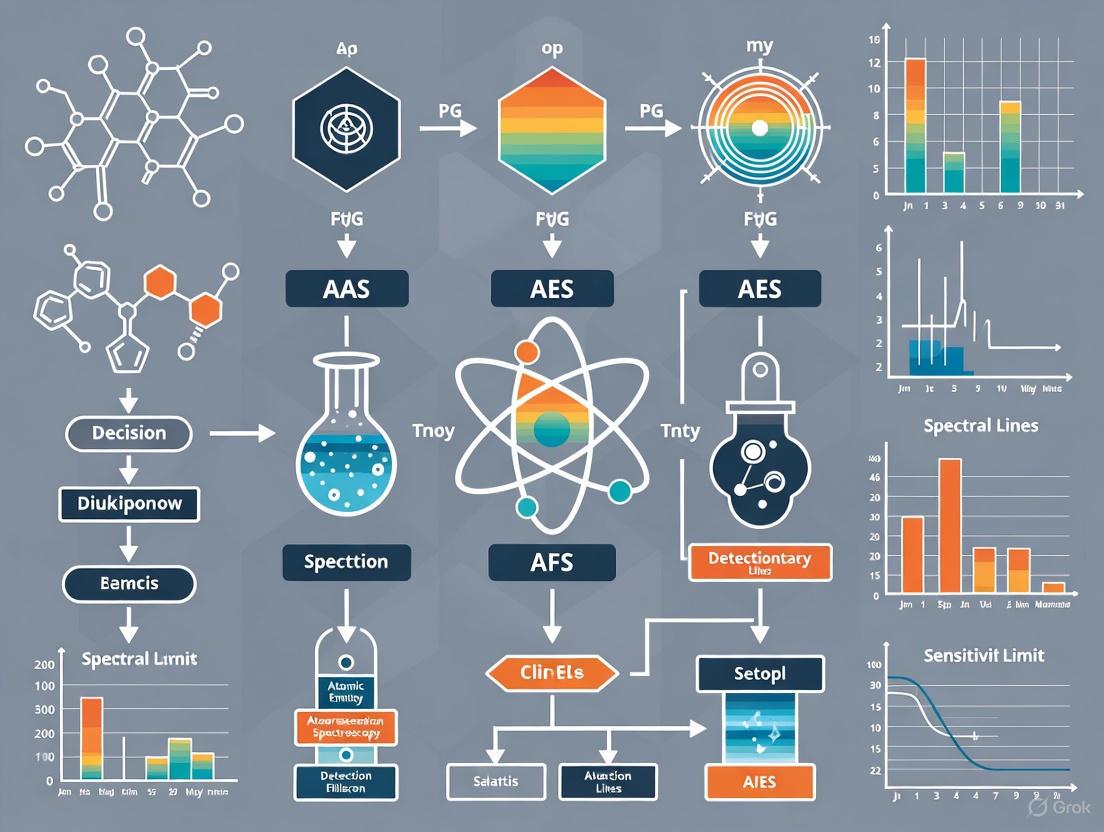

Diagram 1: Fundamental processes of AAS, AES, and ICP techniques.

Comparative Performance Data

The selection of an appropriate atomic spectrometry technique depends on a balance of performance requirements, including sensitivity, sample throughput, and cost [4]. The following tables summarize the key comparative data.

Table 1: Direct comparison of AAS, ICP-OES, and ICP-MS techniques.

| Performance Factor | AAS | ICP-OES | ICP-MS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Detection Limits | Parts-per-million (ppm) range [1] [2] | Parts-per-billion (ppb) range [2] | Parts-per-trillion (ppt) range [2] |

| Multi-Element Capability | Single element analysis [1] [2] | Simultaneous multi-element (up to ~70 elements) [1] [2] | Simultaneous multi-element analysis [2] |

| Analytical Working Range | Narrow dynamic range [2] | Wide linear range (up to 5-6 orders of magnitude) [1] | Very wide linear dynamic range [2] |

| Sample Throughput | Low (sequential analysis) [2] | High (simultaneous analysis) [1] [2] | High (simultaneous analysis) [2] |

| Typical Cost | $25,000 - $80,000 [2] | Higher than AAS [2] | $100,000 - $300,000+ [2] |

| Operation & Skill | Relatively simple, easy to use [1] [2] | Requires skilled operation [2] | Complex, requires highly skilled operation [2] |

Table 2: Analysis of key advantages and limitations.

| Technique | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| AAS | Cost-effective for targeted analysis [2]; High selectivity for individual elements [1]; Well-established, straightforward methodology [1] [2] | Poor multi-element capability [1] [2]; Narrow analytical working range [2]; Requires specific lamp for each element [1] [2] |

| ICP-OES | Excellent multi-element capability [1] [2]; Wide linear dynamic range [1]; Tolerant of complex sample matrices [2] | High instrument and operational cost [2]; Prone to spectral interferences [1]; Requires skilled operator [1] [2] |

| ICP-MS | Ultra-trace detection limits (ppt) [2]; High isotope-specificity and analysis capability [5]; Very high sample throughput [2] | Very high instrument and operational cost [2]; Susceptible to polyatomic and matrix interferences [5]; Highest operator skill requirement [2] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Graphite Furnace AAS for Trace Metal Analysis

This protocol is suitable for achieving parts-per-billion (ppb) detection limits for metals like lead or cadmium in water samples [1].

- Sample Preparation: Digest liquid samples with high-purity nitric acid to a final concentration of 1-2% v/v. For solid samples (e.g., soil, tissue), use a hotplate or microwave digester with nitric acid to create a clear solution [1].

- Instrument Setup: Install the appropriate Hollow Cathode Lamp (HCL) and set the wavelength. Program the graphite furnace temperature steps:

- Calibration: Prepare a blank and at least three standard solutions in the same acid matrix as the samples.

- Analysis & Data Processing: Inject a small aliquot (typically 10-50 µL) of the standard or sample into the graphite tube and run the temperature program. Construct a calibration curve from the standard absorbances and use it to determine unknown concentrations [1].

ICP-OES Analysis with Exact Matching for High Accuracy

This method, informed by NIST protocols, enhances accuracy by minimizing matrix effects [6].

- Sample Preparation: Prepare samples as in 3.1. The final solution should have a total dissolved solid content of <0.2% to prevent nebulizer and torch clogging.

- Internal Standard Selection: Add a non-analyte internal standard element (e.g., Yttrium or Scandium) to all samples and standards at a consistent concentration. This corrects for instrumental drift and physical interferences [1] [6].

- Exact Matching Calibration: Prepare calibration standards so that their analyte concentrations, internal standard concentrations, and acid matrix are matched as closely as possible to the samples. This practice mitigates biases from non-linear instrument responses [6].

- Instrument Operation:

- Nebulization: A peristaltic pump delivers the sample to the nebulizer, creating a fine aerosol [3].

- Plasma Generation: The aerosol is transported to the argon plasma, sustained by a 27-40 MHz RF generator at powers of 750-1600 W [4] [3].

- Analysis: Simultaneously measure analyte and internal standard emission lines using a polychromator with a CCD detector [4].

- Data Processing: The software corrects intensities using the internal standard and calculates concentrations based on the calibration curve. Apply background correction for spectral interferences [1] [6].

Diagram 2: Detailed workflow for high-accuracy ICP-OES analysis.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The accuracy of atomic spectrometric analysis is highly dependent on the purity and quality of reagents and materials used.

Table 3: Key reagents and materials for atomic spectrometry.

| Reagent / Material | Function | Critical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Acids (HNO₃, HCl) | Sample digestion and dissolution to release analytes into solution. | Must be ultra-pure (e.g., trace metal grade) to prevent contamination of trace analytes [1]. |

| Argon Gas | Plasma support gas for ICP; purge gas for optics. | High purity (>99.996%) is essential for stable plasma formation and to minimize spectral background [3]. |

| Hollow Cathode Lamps (HCLs) | Light source for AAS that emits element-specific lines. | A separate HCL is required for each element analyzed. Lamp current and alignment must be optimized [1] [4]. |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Quality control; verification of method accuracy and precision. | CRMs should closely match the sample matrix (e.g., river water, soil) to validate the entire analytical process [6]. |

| Internal Standard Solutions (Y, Sc, In) | Added to samples and standards to correct for instrument drift and matrix effects. | The internal standard must not be present in the original sample and must behave similarly to the analytes [1] [6]. |

Advanced Applications and Research Frontiers

Advanced applications of these techniques often involve coupling them with other technologies to address complex analytical challenges.

- Nuclear Material Characterization: Research by scientists like Benjamin T. Manard involves using laser ablation (LA) coupled with ICP-MS for the direct analysis of uranium particles for nuclear safeguards and forensics. This tandem technique provides elemental and isotopic information with minimal sample preparation [5].

- Speciation Analysis: Combining liquid chromatography (LC) with ICP-MS allows for the determination of specific chemical forms of elements (e.g., toxic vs. non-toxic arsenic species), which is critical for accurate toxicological and environmental risk assessment [5].

- High-Accuracy Metrology: Research at institutions like NIST focuses on protocols like exact matching for HP-ICP-OES to achieve relative expanded uncertainties as low as 0.2%. This is vital for the certification of Standard Reference Materials (SRMs) [6].

Atomic spectrometry techniques offer a powerful suite of tools for elemental analysis, each with a distinct profile of strengths. AAS remains a robust, cost-effective solution for labs requiring routine, single-element analysis at ppm levels. ICP-OES is the workhorse for laboratories needing high-throughput, multi-element analysis with ppb sensitivity and the ability to handle complex matrices. ICP-MS stands as the most powerful technique for applications demanding ultra-trace detection limits, isotopic information, and the highest sensitivity.

The choice of technique is not one of superiority but of appropriateness for the analytical problem at hand. Factors such as required detection limits, number of target elements, sample throughput, budget, and operator expertise must all be weighed. Furthermore, as research advances, the integration of these techniques with complementary technologies like chromatography and laser ablation continues to expand the frontiers of what is possible in elemental analysis, providing scientists with ever-more precise tools for research and drug development.

Atomic spectroscopy is a suite of analytical techniques used to determine the elemental composition of matter. These techniques are founded on the core physics of atomic transitions—the process by which atoms interact with light and energy. When atoms absorb energy, their electrons are promoted from a ground state to a higher-energy, excited state. As these excited electrons return to the ground state, they release energy in the form of photons of characteristic wavelengths. The precise energy of these photons is determined by the unique electronic structure of each element, serving as a fingerprint for its identification [7] [8].

This guide provides an objective comparison of major atomic spectroscopic techniques—Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometry (AAS), Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS), Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS), and X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF). We compare their operational principles, performance, and applications, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies to aid researchers in selecting the appropriate tool for their analytical challenges.

The following table summarizes the fundamental characteristics and performance metrics of the four core techniques.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Atomic Spectroscopic Techniques

| Feature | AAS | ICP-MS | LIBS | XRF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Underlying Atomic Physics | Absorption of light by ground-state atoms in a flame or furnace [8] | Ionization in high-temperature plasma followed by mass-to-charge separation [9] [10] | Atomic emission from a laser-generated plasma [7] [11] | Emission of secondary X-rays after inner-shell electron ejection [12] |

| Multi-Element Capability | Low (Single element) [8] [10] | High [8] [10] | High [7] | High [12] |

| Typical Detection Limits | FAAS: ppm-ppbGFAAS: ppb-ppt [8] | ppb-ppt [8] [10] | ppm [7] | ~0.1 g/kg for P, K, Ca; ~20 mg/kg for Fe, Mn [13] |

| Analytical Speed | Moderate (FAAS) to Slow (GFAAS) [10] | Very High [10] | Very High/Rapid [14] [7] | High/Fast [12] |

| Sample Throughput | Good for FAAS, Low for GFAAS [10] | Very High [9] [10] | High [14] | High [12] |

| Sample Preparation | Liquid, often with dilution [8] | Liquid, often with dilution or digestion [10] | Minimal; solids, liquids, aerosols can be analyzed directly [7] [15] | Minimal; often pressed pellets [12] [13] |

| Cost (Equipment & Operation) | Low to Moderate [8] [10] | High [8] [10] | Moderate [7] | Moderate (Benchtop and handheld options) [13] |

Detailed Technical Comparison and Experimental Data

Performance in Environmental and Biological Analysis

Experimental studies provide direct comparisons of technique performance for real-world applications. A study on metal monitoring in brownfields compared Flame AAS and XRF for analyzing soils contaminated with Pb, Cu, and Zn. While FAAS demonstrated lower limits of detection (LOD), XRF was faster and more practical for field screening, with both providing comparable quantitative results [12]. This illustrates the trade-off between ultra-sensitive laboratory analysis and rapid, in-situ measurement.

In another study, the analytical performance of benchtop and handheld XRF systems was evaluated for the direct analysis of plant materials. Pressed pellets of sugar cane leaves were analyzed for elements including P, K, Ca, Fe, and Mn. Both systems showed comparable figures of merit, with correlation coefficients for test samples ranging from 0.9094 to 0.9948 for the handheld device and 0.9601 to 0.9918 for the benchtop system. Limits of detection were also similar, at approximately 0.1 g/kg for P, K, Ca, and S, and 20 mg/kg for Fe and Mn, demonstrating that handheld systems can provide performance equivalent to benchtop units for direct solid sample analysis [13].

Advances in LIBS and ICP-MS

Recent research has focused on improving the sensitivity and spatial resolution of LIBS. A 2025 study achieved a spatial resolution of 1 μm for mapping metallic coatings by using a picosecond laser with low pulse energy (0.4 μJ) and a tight irradiation interval (0.8 μm). The results showed good agreement with SEM-EDS, demonstrating that optimized laser ablation conditions can push LIBS into the domain of micro-analysis [14]. This advancement is crucial for applications like identifying elemental segregation in steel samples [14].

For ICP-MS, a key development is its hyphenation with other techniques. Laser Ablation ICP-MS (LA-ICP-MS) allows for the direct analysis of solid samples, such as glass fragments in forensic science, with minimal sample preparation and a small sample size of less than 250 nanograms [9]. This combination leverages the spatial resolution of the laser and the exceptional sensitivity and multi-element capability of the ICP-MS.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: High-Resolution Spatial Mapping with Picosecond LIBS

This protocol is adapted from studies on high-resolution microanalysis of steel samples and metallic coatings [14].

- 1. Sample Preparation: The solid sample (e.g., steel, coated metal) is mounted on a stable stage. For high-resolution mapping, a smooth, flat surface is ideal.

- 2. Instrumentation Setup:

- Laser: Utilize a picosecond-pulsed laser (e.g., Nd:YAG at 355 nm).

- Pulse Energy: Adjust to a low level, typically around 0.4 μJ per pulse, to minimize the ablation crater size.

- Repetition Rate: Set to 35 Hz.

- Focusing Optics: Focus the laser beam to a small spot size on the sample surface.

- Spectrometer: Use an echelle spectrograph with a CCD detector to capture the broad spectrum of emitted light.

- 3. Data Acquisition:

- Raster the laser beam across the sample surface with a step size of 1-2 μm.

- At each point, fire the laser and collect the emitted spectrum.

- The time between laser ablation and photon collection (Q-switch delay) is set to minimize continuum radiation.

- 4. Data Analysis: Construct elemental distribution maps by integrating the intensity of a characteristic emission line for each element (e.g., Al, Cu, Mn) at every spatial coordinate.

Diagram 1: Picosecond LIBS workflow for high-resolution spatial mapping.

Protocol: Multi-Element Analysis of Biological Fluids via ICP-MS

This standard protocol is widely used in clinical and biological analysis for the determination of trace elements [15] [10].

- 1. Sample Preparation (Dilution):

- Pipette a small volume of the biological fluid (e.g., 100 μL of serum or urine) into a tube.

- Add a diluent, typically a dilute acid solution such as 1% nitric acid (HNO₃), to achieve a dilution factor between 10 and 50. This keeps the total dissolved solids below 0.2% to prevent nebulizer clogging and matrix effects.

- To aid with dispersion and stability, a surfactant like Triton-X100 may be added to the diluent.

- 2. Instrumentation Setup:

- Nebulizer: A pneumatic nebulizer (e.g., concentric, cross-flow) is used to create the sample aerosol.

- Spray Chamber: Removes larger droplets to ensure only a fine aerosol reaches the plasma.

- Plasma: Argon plasma is sustained in a quartz torch at a temperature of approximately 10,000 K.

- Mass Spectrometer: A quadrupole mass analyzer is tuned to separate ions by their mass-to-charge ratio (m/z).

- 3. Calibration and Quantification:

- Prepare a series of multi-element calibration standards in a matrix matching the sample diluent.

- An internal standard (e.g., Indium, Germanium) is added to all samples and standards to correct for instrument drift and matrix suppression/enhancement.

- The instrument is calibrated, and analyte concentrations are calculated based on the intensity ratio of the analyte to the internal standard.

- 4. Data Analysis: Report elemental concentrations, typically in μg/L (ppb) or nmol/L, for all target elements.

Diagram 2: ICP-MS workflow for multi-element analysis of biological fluids.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Atomic Spectrometry

| Reagent/Material | Function | Common Example Protocols |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Acids (e.g., HNO₃) | Digest organic matrices and dissolve samples; main component of diluents to stabilize trace metals in solution [10]. | Sample digestion for ICP-MS/AAS; preparation of aqueous calibration standards [10]. |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Calibrate instruments and validate analytical methods for accuracy. Critical for robust method validation, especially in nanoparticle analysis [14] [15]. | External calibration in AAS, ICP-MS, XRF; quality control in all quantitative analyses. |

| Argon Gas | Sustain the inductively coupled plasma (in ICP-MS/OES) and act as a carrier gas. High-purity is essential for stable plasma and low background [9]. | Operation of ICP-MS and ICP-OES instrumentation. |

| Hollow Cathode Lamps (HCLs) | Provide the narrow-band, element-specific light source required for atomic absorption measurements [8]. | Elemental analysis by AAS (a separate lamp is required for each element). |

| Internal Standards | Correct for instrument drift and non-spectral interferences; added in known concentrations to all samples, standards, and blanks [9]. | Quantitative analysis by ICP-MS (e.g., using Indium or Germanium). |

| Hydride Generation Reagents (e.g., NaBH₄) | Chemically convert analyte elements (As, Se, Hg) into volatile hydrides or cold vapor for efficient introduction into the instrument [8]. | Determination of hydride-forming elements and mercury by AAS or ICP-MS. |

The selection of an atomic spectroscopy technique is a strategic decision based on the specific analytical requirements. AAS remains a robust and cost-effective choice for laboratories focused on a limited number of elements. ICP-MS is the undisputed leader for ultra-trace multi-element analysis where high sensitivity and throughput are critical. LIBS offers unparalleled speed and minimal sample preparation for direct solid analysis and spatial mapping. XRF provides a non-destructive and portable solution for rapid elemental screening in the lab and field.

Understanding the core physics of atomic transitions empowers scientists to not only operate these instruments but also to interpret data accurately and innovate method development. As the field progresses, the trend is toward hyphenated techniques, miniaturization for field-portable analysis, and advanced data processing with machine learning to extract more information from the fundamental interactions between atoms and energy [14] [15].

Atomic spectroscopy stands as a cornerstone of modern elemental analysis, providing researchers and pharmaceutical developers with critical data for everything from regulatory compliance to fundamental material characterization. The performance, accuracy, and detection limits of these techniques are fundamentally governed by their core instrumental components. This guide provides a detailed comparison of the essential hardware—light sources, atomizers, and detectors—that define the capabilities of major atomic spectroscopic techniques. Understanding these components enables scientists to select the optimal methodology for their specific analytical challenges, whether for routine metal analysis in pharmaceuticals or cutting-edge nanoparticle characterization in environmental samples.

Core Instrumentation Components in Atomic Spectroscopy

The fundamental architecture of atomic spectroscopy instruments shares common components across different techniques, though their implementation and performance characteristics vary significantly. The essential components include: a radiation source for probing atoms, an atomizer to convert samples into free atoms, a wavelength selector to isolate specific spectral lines, and a detector to measure the resulting signal.

The light source provides the specific wavelengths of radiation that ground-state atoms will absorb or against which excited atoms will emit.

- Hollow Cathode Lamps (HCLs): These are the most common radiation sources in Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS). Each HCL contains a cathode made of the element to be determined and an anode sealed in a glass tube filled with an inert gas like neon or argon [16] [8]. When voltage is applied, gas ionisation sputters atoms from the cathode, which then emit their characteristic resonance lines [8]. HCLs provide stable, narrow-bandwidth light tuned precisely to the absorption lines of specific elements [17].

- Electrodeless Discharge Lamps (EDLs): For certain elements requiring higher radiation intensity, EDLs offer superior performance [8]. These lamps contain the target element in a quartz bulb excited by radiofrequency energy, producing brighter and more intense spectral lines than HCLs for elements like arsenic and selenium [8].

- Plasma Sources: In Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectroscopy (ICP-OES) and ICP Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS), the plasma itself serves as the excitation source [2] [18]. The argon plasma, sustained by a radiofrequency coil at temperatures of 6,000-10,000 K, efficiently atomizes and excites sample elements, causing them to emit characteristic photons [2] [18]. This high-temperature environment enables simultaneous multi-element analysis without requiring element-specific lamps.

Atomizers

The atomizer is a critical component that converts the sample into a cloud of free ground-state atoms, essential for both absorption and emission measurements.

- Flame Atomizers: Used in Flame AAS (FAAS), these atomizers typically employ air-acetylene (2,300°C) or nitrous oxide-acetylene (3,000°C) mixtures to produce free atoms [8] [18]. The liquid sample is nebulized to form an aerosol that is introduced into the flame, where thermal energy desolvates, vaporizes, and atomizes the sample [16] [18]. Flame atomizers offer high sample throughput but relatively short atom residence time in the light path [2].

- Graphite Furnace Atomizers: In Graphite Furnace AAS (GFAAS), electrothermal atomization occurs in a small graphite tube heated by electrical current according to a precise temperature program [16] [8]. This approach concentrates the entire sample in the light path with longer atom residence times, delivering detection limits 100-1,000 times lower than flame systems while requiring significantly smaller sample volumes (5-50 µL) [8] [17].

- Plasma Torches: ICP systems use a specialized torch where argon plasma sustains temperatures of 6,000-10,000 K [2] [18]. This extreme environment not only atomizes samples but also efficiently ionizes them, making it ideal for both optical emission and mass spectrometric detection [18]. Plasma torches handle complex matrices including solid-digested samples, wastewater, and biological fluids [2].

- Vapor Generation Systems: Specialized vapor generation accessories exist for volatile elements like mercury and hydride-forming elements (As, Se, Sb). These systems use chemical reduction (typically with sodium borohydride) to convert analytes to volatile species that are then transported to the measurement cell, offering exceptional detection limits for these specific elements [8] [17].

Detectors and Wavelength Selection

Following atomization and excitation, instruments require components to isolate and measure the analytical signals.

- Monochromators: These devices isolate specific wavelengths of light using diffraction gratings [16] [8]. In AAS, monochromators select the precise resonance line from the HCL, excluding other emission lines and stray light [16] [8]. AAS monochromators require less resolution than molecular spectrophotometers due to the narrow line widths of atomic transitions [8].

- Mass Spectrometers: In ICP-MS, a mass spectrometer replaces the optical monochromator, separating ions based on their mass-to-charge ratio [18]. This mass-based separation provides exceptional specificity and enables isotope ratio measurements [19] [18].

- Photomultiplier Tubes (PMTs): Traditional detectors in AAS and ICP-OES, PMTs convert light intensity into electrical signals with high sensitivity and fast response times [16] [8]. Modern systems increasingly employ solid-state detectors like charge-coupled devices (CCDs) or charge-injection devices (CIDs) that can measure multiple wavelengths simultaneously, dramatically improving multi-element analysis capabilities [8].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Major Atomic Spectroscopy Techniques

| Parameter | Flame AAS | Graphite Furnace AAS | ICP-OES | ICP-MS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Detection Limits | ppm to ppb range [18] | ppb to ppt range [8] [18] | ppm to ppb range [18] | ppb to ppt range, some applications to ppq [18] |

| Sample Throughput | High (minutes per sample) [2] | Low (several minutes per element) [2] [8] | High (simultaneous multi-element) [2] | High (simultaneous multi-element) [2] |

| Multi-element Capability | Single element [2] [8] | Single element [2] | Simultaneous [2] [18] | Simultaneous [2] [18] |

| Sample Volume | 1-5 mL [8] | 5-50 µL [8] | 1-5 mL [18] | 1-5 mL [18] |

| Linear Dynamic Range | 2-3 orders of magnitude [8] | 2-3 orders of magnitude [8] | 4-5 orders of magnitude [8] | 8-9 orders of magnitude [8] [18] |

| Initial Instrument Cost | $25,000-$80,000 [2] | Higher than Flame AAS [8] | $100,000+ [2] | $100,000-$300,000+ [2] |

Table 2: Atomizer Comparison and Applications

| Atomizer Type | Temperature/Energy | Key Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flame (FAAS) | 2,000-3,000°C [8] | Routine water analysis, food products, clinical samples [2] | High throughput, simple operation, low cost [2] | Lower sensitivity, limited for refractory elements [8] |

| Graphite Furnace (GFAAS) | Up to 3,000°C [8] | Trace metal analysis in pharmaceuticals, biological tissues [2] [8] | Excellent sensitivity, small sample volumes [8] | Longer analysis time, higher interference potential [8] |

| ICP Torch | 6,000-10,000 K [2] | Environmental monitoring, material science, geochemistry [2] [20] | Handles complex matrices, multi-element capability [2] | High operational cost, requires skilled operator [2] |

| Vapor Generation | Variable (chemical energy) | Hg, As, Se, Sb in environmental and biological samples [8] | Exceptional sensitivity for specific elements [8] | Limited to specific elements, requires chemistry optimization [8] |

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Technique Comparison

Standardized Sample Analysis Protocol

To objectively compare atomic spectroscopy techniques, researchers employ standardized methodologies:

Sample Preparation: Liquid samples are typically digested using nitric acid in closed-vessel microwave systems to ensure complete dissolution of analytes and compatibility with nebulization systems [20]. Solid samples require dissolution through acid digestion or fusion, while powders may be analyzed directly using laser ablation introduction systems [20].

Calibration Approach: External calibration with matrix-matched standards establishes quantitative relationships [8]. The standard additions method compensates for matrix effects by spiking samples with known analyte increments [8]. Internal standards (e.g., Yttrium or Scandium in ICP-MS) correct for instrument drift and matrix suppression effects [8].

Quality Control Measures: Analysis includes certified reference materials (CRMs) to verify accuracy [20]. Continuing calibration verification standards and blanks monitor instrument performance during sequence runs [18]. Method detection limits are determined by analyzing seven replicates of a low-level standard and calculating 3× standard deviation of results [18].

Single-Particle ICP-MS Nanoparticle Characterization

Advanced applications like nanoparticle characterization demonstrate the evolving capabilities of atomic spectroscopy:

Sample Introduction: Highly diluted nanoparticle suspensions (typically 0.01-0.1 mg/L) are introduced via pneumatic nebulization to ensure individual nanoparticle events are temporally resolved [19].

Data Acquisition: Using short integration times (100 µs), time-resolved analysis captures transient signals as discrete nanoparticles enter the plasma [19]. Each nanoparticle generates a signal pulse proportional to its elemental mass [19].

Data Processing: Signals are processed to distinguish dissolved analyte (constant low signal) from particulate signals (transient high-intensity pulses) [19]. Particle size is calculated based on signal intensity using established calibration curves with nanoparticle standards of known size and composition [19].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the fundamental processes shared across atomic spectroscopy techniques, from sample introduction to data output:

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Consumables and Research Reagents in Atomic Spectroscopy

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Hollow Cathode Lamps | Element-specific light source for AAS [16] [8] | Require 15-30 minute warm-up; limited lifetime (~5000 mA hours) [8] |

| High-Purity Gases | Plasma generation (Argon) and atomization (Acetylene, Nitrous Oxide) [2] [18] | Gas purity critical for detection limits; high-purity argon (>99.996%) essential for ICP-MS [18] |

| Graphite Tubes & Cones | Sample containment (Furnace AAS) and interface (ICP-MS) [8] [18] | Consumables requiring regular replacement; platform tubes improve accuracy for complex matrices [8] |

| Certified Reference Materials | Method validation and quality assurance [20] | Essential for accuracy verification; matrix-matched CRMs preferred [20] |

| Nebulizers & Spray Chambers | Sample aerosol generation for introduction into flame or plasma [8] [18] | Different designs (e.g., concentric, cross-flow) optimized for specific sample matrices [8] |

| Chemical Modifiers | Matrix modification in GFAAS to control volatility of analytes/interferents [8] | Palladium/magnesium nitrate commonly used to stabilize volatile elements [8] |

The selection of appropriate instrumentation components in atomic spectroscopy directly determines analytical performance across research and pharmaceutical applications. Flame AAS remains a cost-effective solution for routine single-element analysis, while graphite furnace AAS provides exceptional sensitivity for trace metal determination. ICP-OES delivers robust multi-element capability for diverse sample matrices, and ICP-MS stands as the most sensitive technique for ultratrace analysis and specialized applications like nanoparticle characterization.

Understanding the fundamental roles of light sources, atomizers, and detectors enables scientists to match technique capabilities with analytical requirements. This component-level knowledge supports optimal method development, facilitates troubleshooting, and informs strategic instrument selection for drug development and research laboratories facing increasingly stringent analytical demands. As atomic spectroscopy continues evolving, emerging trends including hyphenated techniques, miniaturization, and automated workflow integration will further expand the analytical toolkit available to researchers.

Atomic Absorption (AAS) and Atomic Emission Spectroscopy (AES) are foundational analytical techniques in elemental analysis, yet they operate on fundamentally different physical principles. AAS measures the absorption of light by free atoms in the gaseous state, while AES measures the intensity of light emitted by excited atoms as they return to lower energy states [1] [21]. The core distinction lies in their energy pathways: AAS relies on the absorption of external radiation to promote electrons to higher energy levels, whereas AES depends on the emission of radiation when excited electrons relax to ground state [22] [23]. This mechanistic difference dictates all subsequent variations in instrumentation, applications, and performance characteristics between the two techniques.

These techniques have revolutionized elemental analysis across diverse fields including pharmaceutical development, environmental monitoring, geochemical analysis, and food safety [24] [25]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these mechanistic differences is crucial for selecting the appropriate method for specific analytical challenges, whether for quantifying trace metals in pharmaceutical compounds or performing multi-element screening in biological samples.

Fundamental Principles and Mechanisms

Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS) Principles

Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy operates on the principle that ground state atoms can selectively absorb light at specific characteristic wavelengths, causing their electrons to jump from the ground state to excited states [26] [22]. The amount of light absorbed at these specific wavelengths is directly proportional to the concentration of the absorbing atoms in the sample, enabling quantitative analysis [1]. The process requires: (1) a source of characteristic radiation specific to the target element, typically a hollow cathode lamp (HCL) or electrodeless discharge lamp (EDL); and (2) an atomizer to convert the sample into a cloud of free, ground state atoms [24] [26].

The absorption phenomenon follows the Boltzmann distribution, where at analytical temperatures (2,000-3,000K), the vast majority of atoms remain in the ground state, making them capable of absorbing resonance radiation [26]. This population distribution explains AAS's exceptional sensitivity for trace element detection. The absorption spectra consist of sharp, discrete lines with narrow widths (approximately 3-10 nm) due to the fixed energy differences between atomic orbitals [22]. Each element has its unique absorption spectrum, providing the technique with high specificity [26].

Atomic Emission Spectroscopy (AES) Principles

Atomic Emission Spectroscopy operates on the fundamentally different principle of measuring light intensity emitted when excited atoms or ions return to lower energy states [27] [23]. In AES, the sample is introduced into a high-energy source (flame, plasma, arc, or spark) that serves both to atomize the sample and excite the atoms to higher electronic states [1] [23]. As these excited state atoms decay to ground state, they emit photons of characteristic wavelengths, with the intensity of emitted radiation being proportional to the concentration of atoms [23].

The excitation process in AES follows the Boltzmann expression: [ \frac{n{\text{upper}}}{n{\text{lower}}} = \frac{g{\text{upper}}}{g{\text{lower}}} e^{-(\varepsilon{\text{upper}}-\varepsilon{\text{lower}})/kB T} ] where (n{\text{upper}}) and (n_{\text{lower}}) represent the number of atoms in higher and lower energy levels, (g) terms are degeneracies, and (\varepsilon) terms are energies of the respective levels [23]. This relationship demonstrates that higher temperature sources produce larger populations of excited atoms, significantly enhancing AES sensitivity. Unlike AAS, AES does not require separate radiation sources for each element, as the emitted light originates from the excited sample atoms themselves [1] [27].

Comparative Energy Pathway Diagrams

The fundamental difference between AAS and AES energy pathways is visualized below.

Instrumentation and Methodologies

Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy Instrumentation

AAS instrumentation consists of four key components configured in sequence: (1) a line source such as a hollow cathode lamp (HCL) that emits element-specific wavelengths; (2) an atomization system that converts the sample into free atoms; (3) a wavelength selection device (monochromator); and (4) a detection and readout system [24] [26]. The hollow cathode lamp contains a cathode made of the target element or coated with it, which emits sharp, element-specific spectral lines when energized [26]. This specific wavelength correspondence is crucial, as it means AAS requires a different HCL for each element analyzed [1].

Atomization, the process of converting sample constituents into free atoms, is achieved primarily through two methods in AAS. Flame AAS uses a controlled combustion environment (typically air-acetylene or nitrous oxide-acetylene) to produce atoms, offering advantages of speed, ease of use, and continuous operation [24] [26]. Electrothermal AAS (graphite furnace) employs a small graphite tube heated by electrical current to high temperatures in a programmed sequence (drying, ashing, atomization) [24]. Graphite furnace AAS provides superior sensitivity (parts-per-billion level) compared to flame AAS (parts-per-million level) because atoms are concentrated in a small volume with essentially 100% atomization efficiency and longer residence times [24]. The graphite furnace temperature program typically includes drying (100-150°C to evaporate solvent), ashing or pyrolysis (350-1200°C to remove organic matter), and atomization (2000-3000°C to produce free atoms) stages [26].

Atomic Emission Spectroscopy Instrumentation

AES instrumentation differs fundamentally in that it requires only three main components: (1) an excitation source that both atomizes and excites the sample; (2) a wavelength selection system; and (3) a detection system [1] [27]. Unlike AAS, AES does not require an external radiation source since the emitted light originates from the excited sample atoms themselves [23]. Modern AES employs several excitation sources, with inductively coupled plasma (ICP) being most prominent for its superior performance.

Inductively coupled plasma (ICP) sources generate high-temperature plasmas (6,000-10,000 K) by ionizing a flowing stream of argon gas with an induction coil carrying an alternating current [1] [23]. The resistive heating as charged particles move through the gas maintains the plasma's extreme temperature, which provides more efficient atomization and a higher population of excited states compared to flame sources [23]. Flame emission uses combustion flames similar to AAS but operates at lower temperatures (2,000-3,000 K), making it suitable mainly for easily excitable alkali and alkaline earth metals [23]. Spark and arc AES are used primarily for direct analysis of conductive solid samples, where an electric discharge both vaporizes and excites the sample material [23].

Comparative Instrumentation Workflow

The instrumental configurations for AAS and AES highlight their mechanistic differences, as shown in the workflow below.

Analytical Performance Comparison

Quantitative Performance Metrics

The mechanistic differences between AAS and AES translate directly to distinct analytical performance characteristics, as summarized in the table below.

| Performance Parameter | Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS) | Atomic Emission Spectroscopy (AES) |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Mechanism | Absorption of external radiation by ground state atoms [22] | Emission of radiation from excited atoms returning to ground state [23] |

| Detection Limits | Flame AAS: ppm range (μg/mL)Graphite Furnace AAS: ppb range (ng/mL) [24] | ICP-AES: sub-ppb to ppm range [27] |

| Linear Dynamic Range | 2-3 orders of magnitude [24] [26] | 5-6 orders of magnitude [1] |

| Multi-element Capability | Single element analysis (requires changing HCL) [1] | Simultaneous multi-element analysis (up to 70 elements) [1] [27] |

| Spectral Interferences | Less prone to spectral interferences due to narrow HCL emission lines [1] | More spectral interferences due to dense emission line spectra [1] [27] |

| Sample Throughput | Relatively slow (sequential element analysis) [24] | High throughput (simultaneous multi-element detection) [1] |

| Operational Costs | Lower initial investment and operating costs [1] | Higher initial investment and operating costs [1] [27] |

Interference Mechanisms and Mitigation

Both techniques experience analytical interferences, but of different natures. AAS primarily suffers from matrix effects where sample constituents affect atomization efficiency, particularly in graphite furnace applications [24]. These include molecular absorption (background absorption from molecular species), chemical interferences (formation of stable compounds that resist atomization), and physical interferences (variations in sample viscosity or surface tension affecting nebulization) [24]. Modern AAS addresses these through background correction systems (deuterium arc or Zeeman-effect) and matrix modifiers that stabilize the analyte or modify the matrix [24] [26].

AES experiences primarily spectral interferences due to overlapping emission lines from different elements or background emission from plasma gases and molecular species [1] [27]. ICP-AES mitigates these through high-resolution spectrometers, background correction algorithms, and sometimes chemical separation of interfering elements [27]. The high temperature of ICP sources significantly reduces chemical interferences compared to flame-based methods but introduces greater spectral complexity [23].

Experimental Protocols and Applications

Detailed Methodologies

Flame AAS Protocol for Trace Metal Analysis: Sample preparation begins with conversion to aqueous solution through acid digestion (typically using nitric acid for organic matrices or combination acids like HNO₃-HCl for inorganic materials) [24] [26]. The liquid sample is aspirated into the nebulizer, which creates a fine aerosol mixed with fuel and oxidant gases. The aerosol-fuel mixture travels to the burner head where combustion occurs (typical temperatures: air-acetylene ~2,300°C, nitrous oxide-acetylene ~2,700°C) [26]. Ground state atoms in the flame absorb resonance radiation from the HCL, and the attenuation of light intensity is measured by the detector. Quantification employs external calibration with matrix-matched standards or standard addition methodology to compensate for matrix effects [1].

ICP-AES Protocol for Multi-element Analysis: Samples are typically digested to create aqueous solutions (exception being direct solid analysis by laser ablation) [27] [23]. A peristaltic pump delivers the sample solution to a nebulizer that creates aerosol, with larger droplets removed by a spray chamber to enhance efficiency [23]. The fine aerosol is transported to the argon plasma torch where temperatures of 6,000-10,000 K cause complete atomization and excitation [1] [23]. Emitted light is dispersed by a grating polychromator capable of measuring multiple wavelengths simultaneously, with detector arrays (typically CCD or CID) capturing the complex emission spectrum [27]. Quantification uses multi-element calibration standards with internal standardization (e.g., adding yttrium or scandium) to correct for matrix effects and instrumental drift [1].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for implementing these analytical techniques.

| Research Reagent/Material | Function in Analysis | Application Technique |

|---|---|---|

| Hollow Cathode Lamps (HCLs) | Emit element-specific narrow line spectra for absorption measurements [26] | AAS |

| Graphite Furnace Tubes | Electrothermal atomization platform for high-sensitivity analysis [24] | Graphite Furnace AAS |

| Matrix Modifiers (e.g., Pd, Mg, NH₄H₂PO₄) | Stabilize volatile analytes or modify sample matrix during thermal treatment [24] | Graphite Furnace AAS |

| ICP Torches (Quartz) | Contain and sustain high-temperature argon plasma for atomization/excitation [23] | ICP-AES |

| Nebulizers & Spray Chambers | Generate fine aerosol from liquid samples and select optimal droplet size [23] | Flame AAS, ICP-AES |

| High-Purity Acids (HNO₃, HCl) | Digest samples to create aqueous solutions for analysis [24] [27] | Sample Preparation for AAS/AES |

| Certified Reference Materials | Validate method accuracy and perform instrument calibration [1] | Quality Assurance for AAS/AES |

Application Domains

AAS finds particular utility in targeted element analysis where specific metals need quantification at trace levels. Common applications include determination of toxic heavy metals (Pb, Cd, As, Hg) in pharmaceuticals and biological fluids [24] [22], quality control of metallurgical products, analysis of trace elements in environmental samples (waters, soils), and nutritional mineral analysis in food products [24]. Graphite furnace AAS is especially valuable when sample volume is limited or when ultra-trace detection is required [24].

AES, particularly ICP-AES, excels in multi-element screening and analysis of complex samples. Key applications include comprehensive elemental analysis of geological materials, simultaneous determination of multiple elements in clinical and biological samples, characterization of advanced materials (e.g., catalyst metals, semiconductor materials), petroleum products analysis, and high-throughput quality control of industrial materials [27] [23]. Spark AES specializes in direct analysis of metallic alloys for production quality control in foundry and metal casting facilities [27] [23].

Atomic Absorption and Atomic Emission Spectroscopy, while both serving elemental analysis, operate on fundamentally different mechanistic principles that dictate their respective strengths and limitations. AAS, measuring absorption by ground state atoms, offers exceptional sensitivity and selectivity for individual element quantification, particularly for metals, with relatively simple instrumentation [24] [22]. AES, measuring emission from excited atoms, provides superior multi-element capability and wider linear dynamic range, albeit with more complex instrumentation and greater spectral interference potential [1] [23].

The choice between these techniques depends fundamentally on analytical requirements. For targeted analysis of specific elements at trace concentrations, particularly in routine laboratory settings with budget constraints, AAS remains the technique of choice [1]. For comprehensive elemental characterization of complex samples requiring simultaneous multi-element detection, ICP-AES provides unparalleled capabilities [27]. Understanding these core mechanistic differences enables researchers and drug development professionals to select the optimal analytical approach for their specific elemental analysis challenges.

Sample introduction and atomization are critical steps in atomic spectroscopy, directly influencing the sensitivity, accuracy, and precision of elemental analysis. These processes convert solid or liquid samples into free ground-state atoms that can be measured by spectroscopic techniques. The fundamental challenge lies in efficiently introducing the sample into the atomization source while minimizing interferences and maximizing atomization efficiency. Researchers must select the optimal methodology based on their specific analytical requirements, including detection limit needs, sample matrix, and available instrumentation.

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of major sample introduction and atomization techniques, including pneumatic nebulization (PN), electrothermal atomization in graphite furnaces, and vapor generation methods such as hydride generation (HG) and photochemical vapor generation (PVG). We present experimental data, detailed methodologies, and performance characteristics to inform method selection for elemental analysis research and drug development applications.

Performance Comparison of Sampling Modes

The performance characteristics of different sampling modes vary significantly, requiring researchers to select methods based on their specific analytical needs for introduction efficiency, detection limits, and reproducibility. The table below summarizes key performance metrics for Se and Te determination using different sampling modes coupled with ICP-MS.

Table 1: Performance comparison of sampling modes for Se and Te determination by ICP-MS

| Sampling Mode | Introduction Efficiency (Se) | Introduction Efficiency (Te) | Best LOD (μg L⁻¹) | Reproducibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pneumatic Nebulization (PN) | 4.71% | 4.58% | Varies by element | Best |

| Hydride Generation (HG) | 57.01% | 53.02% | Varies by element | Poorest |

| Photochemical Vapor Generation (PVG) | 45.38% | 38.84% | 0.001 (both Se and Te) | Good |

Method Selection Guidelines for Different Sample Types

Analysis of 14 geological certified reference materials (CRMs) provides practical guidance for method selection based on concentration levels:

- For samples with Se > 0.1 μg g⁻¹ and Te > 0.05 μg g⁻¹, both PN and PVG sampling modes can obtain satisfactory results, with PN being more convenient for routine analysis. [28]

- For samples with Se ≤ 0.1 μg g⁻¹ and Te ≤ 0.05 μg g⁻¹, HG or PVG sampling modes are recommended after enrichment pretreatment to achieve adequate detection limits. [28]

- PN mode offers the best reproducibility but has limited introduction efficiency, making it suitable for samples with higher analyte concentrations. [28]

- HG provides the highest introduction efficiency but suffers from poor reproducibility, making it ideal for ultra-trace analysis where reproducibility can be managed through careful method optimization. [28]

- PVG represents a balanced approach with good introduction efficiency and reproducibility, along with excellent detection limits, making it suitable for a wide range of applications. [28]

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Pneumatic Nebulization with ICP-MS

Principle and Workflow: Pneumatic nebulization converts liquid samples into an aerosol using the kinetic energy of a high-velocity gas stream, typically argon. This aerosol is then introduced into the ICP-MS for atomization, ionization, and detection.

Optimized Experimental Protocol:

- Instrument Parameters: Optimize RF power, sampling depth, and collision gas flow rate for specific analytes and matrices. [28]

- Sample Introduction: Introduce 3-5 mL of liquid sample for flame AAS or 0.5-10 μL for graphite furnace AAS. [29]

- Nebulization Process: The sample is drawn up through the nebulizer and broken into droplets by the high-velocity gas stream.

- Spray Chamber: Larger droplets are removed through impact, allowing only the finest aerosol (typically 1-2% of original sample) to reach the plasma. [29]

- Atomization and Detection: The aerosol is desolvated, vaporized, and atomized in the plasma, with resulting ions separated by mass-to-charge ratio in the mass spectrometer.

Performance Characteristics: PN provides introduction efficiency of approximately 4.5-5% for elements like Se and Te, with the best reproducibility among the three methods compared. [28]

Graphite Furnace Atomization

Principle and Workflow: Graphite furnace atomic absorption spectroscopy (GFAAS) uses an electrically heated graphite tube to atomize samples through a controlled temperature program. The entire sample is vaporized within the tube, creating a transient cloud of atoms that absorb light from the source lamp.

Optimized Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Introduction: A small volume (typically 0.5-10 μL) is injected into the graphite tube through a sampling hole. [29]

- Drying Stage: Heat to ~100°C to evaporate the solvent (typically 1-2 minutes). [29]

- Ashing Stage: Heat to ~800°C to remove organic matrix and other interferents (seconds to 1 minute). [29]

- Atomization Stage: Rapidly heat to 2000-3000°C to produce free ground-state atoms (milliseconds to seconds). [29]

- Absorption Measurement: Measure atomic absorption during the atomization stage, with integrated peak area used for quantification. [29]

- Cleaning Stage: High-temperature cleaning to remove residual matrix before next injection.

Performance Characteristics: GFAAS provides exceptional sensitivity with detection limits in the sub-ppb range and requires minimal sample volume. The technique is susceptible to matrix effects that require careful method development, including the use of matrix modifiers and background correction systems. [30] [31] [29]

Table 2: Comparison of flame AAS and graphite furnace AAS characteristics

| Parameter | Flame AAS | Graphite Furnace AAS |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Limit | ppm - ppb levels | sub-ppb levels |

| Sample Throughput | 15-20 sec per element | 3-4 minutes per element |

| Sample Volume | Few mL | Few μL |

| Tolerance for Dissolved Solids | 0.5-3% | ~20% (slurries possible) |

| Precision | Good | Lower than flame |

| Capital Cost | Moderate | Higher |

| Chemical Interferences | Many | Many |

| Physical Interferences | Some | Very Few |

Vapor Generation Techniques

Principle and Workflow: Vapor generation techniques convert target elements into volatile species through chemical or photochemical reactions before introduction to the atomization/excitation source.

Hydride Generation (HG) Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Pre-treatment: Reduce analytes to appropriate oxidation states (e.g., Se(VI) to Se(IV), As(V) to As(III)).

- Hydride Formation: React sample with sodium borohydride in acid medium to form volatile hydrides.

- Gas-Liquid Separation: Separate volatile hydrides from liquid matrix using inert gas stream.

- Transport to Atomizer: Transfer hydrides to heated quartz tube atomizer or plasma source.

- Atomization and Detection: Decompose hydrides to free atoms for measurement.

Photochemical Vapor Generation (PVG) Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare sample in low molecular weight organic acid medium (e.g., formic or acetic acid).

- Photochemical Reaction: Expose to UV irradiation to generate volatile species.

- Gas-Liquid Separation: Separate volatile species from liquid matrix.

- Transport and Detection: Transfer to detector for quantification.

Performance Characteristics: HG provides very high introduction efficiency (53-57% for Se and Te) but suffers from poorer reproducibility compared to other methods. PVG offers a good balance with introduction efficiencies of 39-45% for Se and Te, excellent detection limits (0.001 μg L⁻¹), and good reproducibility. [28]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential reagents and materials for sample introduction and atomization methods

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Graphite Tubes | Electrothermal atomization surface | GFAAS analysis of trace metals |

| Matrix Modifiers | Modify sample matrix to stabilize analytes or volatilize interferents | Pd/Mg modifiers for volatile elements in GFAAS |

| Sodium Borohydride | Reducing agent for hydride generation | HG for As, Se, Sb, Bi determination |

| Low Molecular Weight Organic Acids | Reactants for photochemical vapor generation | Formic acid for PVG of Se and Te |

| Certified Reference Materials | Method validation and quality control | NBS SRM 1643 (Trace Metals in Water) for GFAAS verification [30] |

| Argon Gas | Inert atmosphere for graphite furnaces and plasma generation | Prevents oxidation in GFAAS, plasma gas for ICP |

| Hollow Cathode Lamps | Element-specific light sources for AAS | Element-specific determination by AAS |

Comparative Analysis of Interference Effects

Different sample introduction and atomization methods exhibit varying susceptibility to spectroscopic and non-spectroscopic interferences, which significantly impacts method selection for specific applications.

Spectral and Chemical Interferences

Background Correction in GFAAS: An important and frequent source of error is the failure of the background correction system to perform its role. Zeeman-effect background correction provides significant advantages by using a single light source, avoiding the adjustment problems associated with continuum-source correction systems. [30]

Vapor Phase Interferences: The requirement for full atomization of the analyte implies that matrix components will not form strong vapor phase bonds that remove the analyte from the atomic state required for AAS. Halides form such vapor phase bonds with many metals and this continues to be troublesome. Matrix modifiers are used to stabilize the analyte so that a char step can be used to remove much of the halide. [30]

Atomization Efficiency: For most elements determined in the furnace, the efficiency of atomization is very close to 100%. Some exceptions include rare earth elements and some alkali and alkaline earth elements, which cannot yet be determined in the furnace with confidence that the matrix will not affect the efficiency. [30]

Physical Interferences

Nebulization Efficiency: In flame AAS and ICP techniques, physical properties of the sample solution including viscosity, surface tension, and density can significantly affect nebulization efficiency and subsequent transport to the atomization source. Samples with high dissolved solids or organic solvents may produce different analytical responses compared to aqueous standards. [29]

Transport Effects: Vapor generation techniques largely eliminate physical interferences related to sample transport by separating the analyte from the sample matrix before introduction to the atomizer. This represents a significant advantage for complex sample matrices. [28]

Quality Assurance and Method Validation

Quality Control Measures

Characteristic Mass: The characteristic mass, defined as the mass of analyte in picograms that produces a 1% absorption (0.0044 absorbance) signal, serves as an important quality assurance parameter in GFAAS. Obtaining the expected characteristic mass for a particular analyte confirms proper instrument function. [30]

Reference Materials: Routine use of certified reference materials such as NBS Standard Reference Material 1643 (Trace Metals in Water) provides essential verification of analytical conditions and standards. [30]

System Suitability Tests: Elements such as Ag, Cu, and Cr can be used for test procedures to confirm that instruments are working well each day and that different instruments are working similarly. [30]

Optimization Strategies

ICP-MS Operating Parameters: For all sampling modes coupled with ICP-MS, critical parameters including RF power, flow rate of collision gas, and sampling depth must be optimized for specific analytical requirements. [28]

Temperature Programming: In GFAAS, careful optimization of drying, ashing, and atomization temperatures is essential for maximizing sensitivity while minimizing interferences. [29]

Chemical Conditions: For vapor generation techniques, parameters including acid concentration, borohydride concentration, and for PVG, UV exposure time and organic acid concentration must be systematically optimized. [28]

Technique Selection and Real-World Applications: From Routine QC to Ultra-Trace Analysis

Atomic Absorption Spectrometry (AAS) stands as a cornerstone technique for elemental analysis in research and industrial laboratories worldwide. Based on the fundamental principle that free ground-state atoms can absorb light at specific wavelengths, AAS provides quantitative measurements of elemental concentrations in diverse sample matrices [8]. The technique's high selectivity for specific metals and relatively low cost compared to other elemental analysis techniques has maintained its popularity despite the development of multi-element techniques like ICP-OES and ICP-MS [8].

The mathematical foundation of AAS is the Beer-Lambert law, which states that absorbance (A) is directly proportional to the concentration (c) of the absorbing species: A = εbc, where ε is the molar absorptivity constant and b is the optical path length [8]. In practical terms, this relationship allows analysts to determine elemental concentrations by measuring the absorption of light at characteristic wavelengths as it passes through a cloud of atomized sample.

This guide focuses on two principal atomization techniques: Flame AAS (FAAS) and Graphite Furnace AAS (GFAAS). Each method offers distinct advantages and limitations, making them suitable for different analytical scenarios in pharmaceutical and environmental testing. Understanding their fundamental differences in detection capability, analysis speed, and operational requirements enables researchers to select the optimal technique for their specific analytical challenges [32].

Fundamental Principles and Comparative Performance

Core Technological Differences

The fundamental distinction between Flame and Graphite Furnace AAS lies in their atomization mechanisms—how they convert a liquid sample into free atoms for measurement.

Flame AAS (FAAS) operates as a continuous system that steadily aspirates sample liquid and sprays it into a precisely controlled flame. The flame's intense heat (typically 2,000-2,300°C for air-acetylene or over 3,000°C for nitrous oxide-acetylene) instantly vaporizes the sample, creating a steady-state population of free atoms [32] [8]. This continuous process generates highly stable, repeatable signals ideal for high-throughput analysis of samples with higher analyte concentrations [32].

Graphite Furnace AAS (GFAAS), also known as Electrothermal AAS, employs a discrete, multi-stage system. A tiny droplet of sample (typically 5-50 µL) is placed inside a small graphite tube, which then undergoes a carefully programmed heating sequence through several stages: drying (solvent removal), pyrolysis (organic matrix decomposition), and atomization (rapid heating to create free atoms) [32] [8]. This process concentrates the analyte in a small area, resulting in significantly enhanced sensitivity compared to flame techniques.

Comprehensive Performance Comparison

The table below summarizes the key performance characteristics and operational differences between Flame AAS and Graphite Furnace AAS:

Table 1: Performance Comparison Between Flame AAS and Graphite Furnace AAS

| Parameter | Flame AAS (FAAS) | Graphite Furnace AAS (GFAAS) |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Capability | Parts-per-million (ppm) levels | Parts-per-billion (ppb) & parts-per-trillion (ppt) levels |

| Analysis Speed | Very fast (seconds per sample); ideal for large sample batches | Considerably slower (minutes per sample) |

| Sample Volume | Requires continuous sample flow (typically 1-5 mL) | Very small discrete volumes (5-50 µL) |

| Precision | Highly stable, producing very repeatable signals (RSD 1-2%) | More susceptible to small variations between runs |

| Initial Investment | Lower | Significantly higher |

| Operational Costs | Lower (common gases, fewer consumables) | Higher (high-purity argon, graphite tubes) |

| Best Application | Routine analysis of higher-concentration samples | Specialized analysis of trace-level elements |

| Multi-element Capability | Single element typically | Single element typically |

The exceptional sensitivity of GFAAS—typically 10-1000 times greater than FAAS—comes from its efficient atomization process and the concentration of analyte atoms within the small graphite tube [8]. However, this enhanced sensitivity comes at the cost of analysis speed and precision. FAAS benefits from a continuous, stable sample introduction system that constantly averages the signal over several seconds, while GFAAS relies on discrete injection of single tiny droplets where any minor variation in volume or placement can impact individual results [32].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Graphite Furnace AAS Protocol for Lead in Biological Samples

Graphite Furnace AAS demonstrates particular value in clinical and environmental toxicology, where detection of trace metals in complex matrices is required. The following optimized protocol for lead determination in blood and urine exemplifies a robust GFAAS methodology [33].

Table 2: Optimized GF-AAS Instrument Parameters for Lead Determination

| Parameter | Setting |

|---|---|

| Instrument | Varian Spectra AA-880 with GTA-100 atomizer |

| Wavelength | 283.3 nm |

| Slit Width | 0.5 nm |

| Lamp Current | 10 mA |

| Background Correction | Deuterium lamp |

| Sample Volume | 10 µL |

| Total Injection Volume | 15 µL |

| Calibration Range | 10.0-100.0 µg/L |

| Atomization Temperature | 2,100°C |

Sample Preparation Protocol:

- Blood Samples: Mix 200 µL of blood with 800 µL 5% anti-foam B solution and 1,000 µL 1.6 M solution of 65% HNO₃. Allow to stabilize for 10 minutes, then centrifuge for 5 minutes at 2,884 x g RCF. Collect supernatant for analysis.

- Urine Samples: Treat 9 mL of urine with 1 mL of 65% HNO₃. Allow to stabilize for 20 minutes, then centrifuge for 10 minutes at 2,884 x g RCF. Collect supernatant for analysis.

Graphite Furnace Temperature Program:

- Step 1 (Drying): 40°C for 1.0 second, 85°C for 5.0 seconds, 95°C for 40.0 seconds, 120°C for 10.0 seconds

- Step 2 (Pyrolysis): 400°C for 5.0 seconds, 400°C for 1.0 second

- Step 3 (Atomization): 2,100°C for 1.0 second (read signal initiated)

- Step 4 (Cleaning): 2,100°C for 3.0 seconds

This validated method achieved a linear range of 10.0-100.0 µg/L with a correlation coefficient of 0.999, making it suitable for monitoring chelation therapy in cases of acute lead poisoning [33].

Flame AAS Protocol for Copper in Water Samples

Flame AAS serves as an efficient technique for metal detection in environmental waters, where concentrations often fall within its detection range. The following protocol for copper determination exemplifies FAAS application in environmental monitoring [34].

Instrument Configuration:

- Nebulizer: Standard pneumatic nebulizer

- Flame Gases: Air-acetylene (2,300°C) for conventional determination; Nitrous oxide-acetylene (3,000°C) for refractory elements

- Wavelength: 324.8 nm (primary copper line)

- Spectral Bandwidth: 0.5-1.0 nm

- Calibration: External standards in matrix-matched solutions

Sample Preparation and Analysis:

- Water Samples: Filter through 0.45 µm membrane filter, acidify to pH <2 with ultrapure nitric acid

- Wastewater Samples: Digest with HNO₃-H₂O₂ at 95°C for 2 hours, then dilute to appropriate volume

- Analysis: Aspirate standards and samples, measure absorbance at 324.8 nm

Researchers have enhanced FAAS detection limits for copper using various pre-concentration techniques. Solid-phase extraction achieved detection limits of ng/mL level, while liquid-liquid microextraction reached 0.60 μg/L for 10 mL water samples [34]. Cloud point extraction enabled determination with detection limits of 1.5 µg/L and 0.04 µg/L in different studies [34].

AAS in Pharmaceutical Cleaning Validation

AAS finds important applications in pharmaceutical quality control, particularly in cleaning validation where residual active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) must be quantified. The technique is especially valuable when APIs contain metal ions as part of their structure [35].

Methodology for Metal-Containing APIs:

- Esomeprazole Magnesium: Developed electrothermal AAS methods in both aqueous and ethanol medium for magnesium determination

- Lithium Carbonate: Implemented flame AAS for lithium determination in rinse samples

- Sample Preparation: Used 1% aqueous or ethanol solution of nitric acid for esomeprazole magnesium; 0.1% aqueous solution of nitric acid for lithium carbonate

These validated methods demonstrated accuracy, precision, and detection limits at the microgram level, successfully applying to rinse samples from cleaning procedures in pharmaceutical manufacturing [35].

Analytical Workflows

The analytical process for both FAAS and GFAAS follows a systematic workflow from sample preparation to final reporting. The diagram below illustrates the generalized AAS testing workflow, as implemented in professional laboratory services:

Figure 1: AAS Testing Workflow

This standardized workflow ensures reliable, reproducible results through careful quality control at each stage. The process begins with thorough consultation to define analytical requirements, followed by appropriate sample reception and pre-treatment, which may include dissolution, dilution, or digestion depending on sample type [36]. Method development and instrument calibration establish optimal analysis conditions, while rigorous testing with multiple repetitions ensures data stability. Comprehensive data analysis and validation precede the preparation of formal reports containing sample information, test results, and methodological details [36].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful AAS analysis requires high-purity reagents and specialized materials to prevent contamination and ensure accurate results. The following table details essential research reagent solutions and materials for AAS experiments:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for AAS Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Acids | Sample digestion and preservation; preparation of standard solutions | Nitric acid with metal content <0.00005% [33] |

| Certified Reference Materials | Method validation; quality control | Certified pure metals or salt standards with known purity [33] |

| Matrix Modifiers | Enhance volatility of interfering matrix components in GFAAS | Palladium, magnesium nitrate, or ammonium phosphate [33] |

| Graphite Tubes | Atomization cell for GFAAS | High-purity electrographite with platform; consumable requiring regular replacement [32] |

| Hollow Cathode Lamps | Element-specific light source | Cathode made of target element; specific to each analyzed element [8] |

| Calibration Standards | Instrument calibration; quantitative analysis | Serial dilutions from stock standard solutions; matrix-matched to samples [8] |

| High-Purity Gases | Flame support (FAAS) and purge gas (GFAAS) | Acetylene, air, nitrous oxide (FAAS); high-purity argon (GFAAS) [32] [8] |

Proper selection and use of these reagents is critical for obtaining reliable data. For pharmaceutical applications, reagents must meet appropriate regulatory standards, while environmental methods may require different purity grades depending on detection limits [36] [33].

Application-Specific Considerations

Pharmaceutical Applications

In pharmaceutical analysis, AAS techniques address specific quality control challenges:

Cleaning Validation: AAS determines residual metal-containing APIs on manufacturing equipment surfaces. Techniques must demonstrate accuracy, precision, and detection limits appropriate for established acceptance criteria [35].

Raw Material Testing: FAAS and GFAAS quantify metal catalysts and impurities in excipients and active pharmaceutical ingredients, ensuring compliance with pharmacopeial limits [36].

Product Quality Control: Monitoring essential minerals in formulations or trace metal impurities in final products, with methodologies validated according to regulatory guidelines [36].

Environmental Applications

Environmental monitoring presents distinct challenges that influence technique selection:

Regulatory Compliance Testing: GFAAS enables detection of heavy metals like lead, cadmium, and arsenic at levels required by drinking water standards (e.g., lead detection in drinking water down to single-digit parts-per-billion) [32].

Water Quality Assessment: FAAS provides rapid analysis of higher-concentration elements in surface waters, wastewater, and seawater, with copper detection limits enhanced through pre-concentration techniques [34].

Complex Matrix Analysis: GFAAS programming capabilities allow handling of complex environmental samples like wastewater with high salt content through optimized thermal treatment steps that remove interfering matrix components before atomization [32].

Flame and Graphite Furnace AAS represent complementary rather than competing analytical techniques, each with distinct advantages for specific applications in pharmaceutical and environmental testing. FAAS offers speed, simplicity, and cost-effectiveness for higher-concentration analytes and routine analysis, while GFAAS provides exceptional sensitivity for trace metal determination when sample volume is limited or regulated limits require parts-per-billion detection capabilities.

The selection between these techniques should be guided by specific analytical requirements: required detection limits, sample volume availability, matrix complexity, throughput needs, and operational budget. For laboratories facing diverse analytical challenges, both techniques may represent essential tools in the elemental analysis arsenal, each addressing different segments of the concentration spectrum and application scenarios.

As atomic spectroscopy continues to evolve, both FAAS and GFAAS maintain their relevance in modern laboratories through ongoing technical improvements and their established reputation for robust, reliable metal analysis across diverse sample matrices.

Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry (ICP-OES) has stood as one of the most widely used atomic spectroscopy techniques for decades, renowned for its robust, rapid, multi-element analysis capabilities for solutions and digested solid samples [37]. The technique utilizes inductively coupled plasma—an ionized gas containing free electrons and cations at high temperatures—to generate excited atoms and ions that emit characteristic electromagnetic radiation [38]. Each element emits photons at distinct wavelengths, and the intensity of this emitted light is directly correlated to the element's concentration, enabling precise quantification [38]. As atomic spectroscopic techniques have evolved, ICP-OES has secured a distinct position between simpler single-element techniques and more sensitive but complex multi-element methods, particularly valued in industrial settings for its balance of performance, robustness, and operational efficiency [39] [40].

Comparative Analysis: ICP-OES vs. Alternative Techniques

Technical Comparison Framework