Advancing Forensic Science: A Strategic Framework for Improving Inter-laboratory Reproducibility and Technology Readiness

This article addresses the critical challenge of inter-laboratory reproducibility in forensic science, a cornerstone for reliable evidence and judicial integrity.

Advancing Forensic Science: A Strategic Framework for Improving Inter-laboratory Reproducibility and Technology Readiness

Abstract

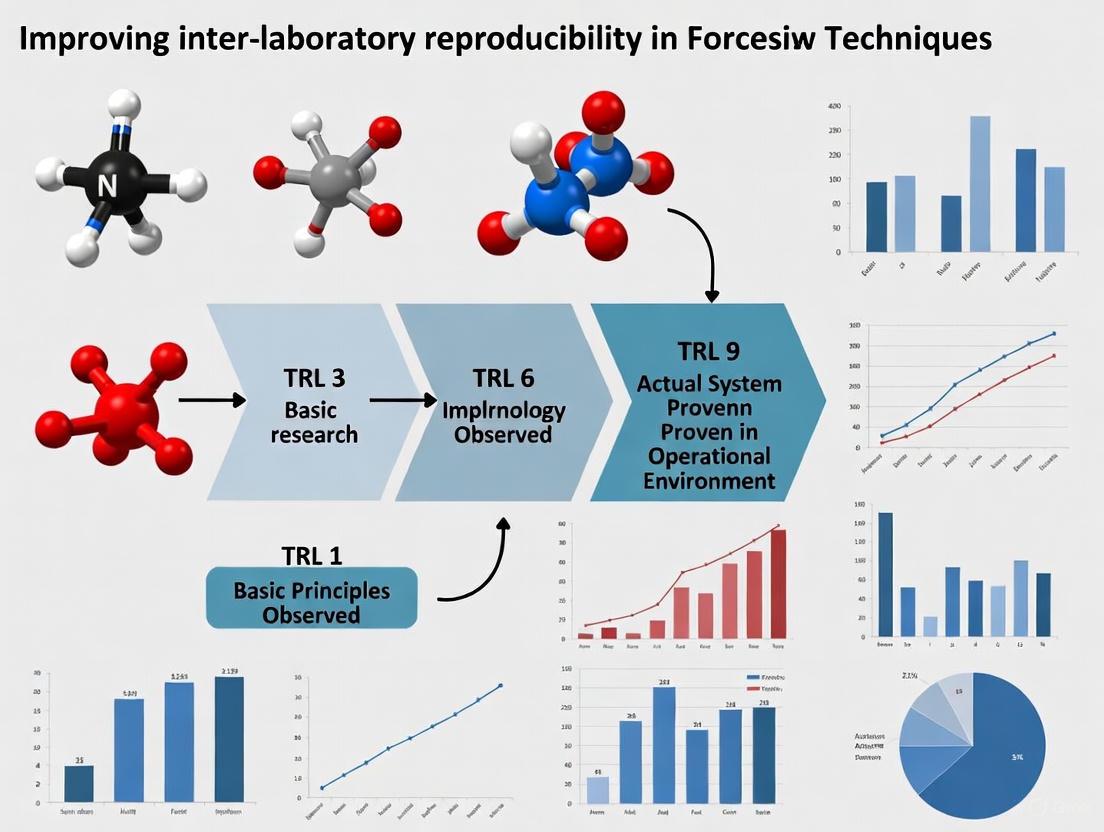

This article addresses the critical challenge of inter-laboratory reproducibility in forensic science, a cornerstone for reliable evidence and judicial integrity. It synthesizes current research, strategic frameworks, and practical case studies to provide a comprehensive roadmap for researchers and forensic professionals. The content explores the foundational causes of variability, details methodological innovations and standardized protocols, offers troubleshooting strategies for common pitfalls, and establishes robust validation and comparative assessment criteria. By aligning forensic techniques with defined Technology Readiness Levels (TRL), this guide aims to bridge the gap between research validation and widespread, reliable implementation in casework, ultimately enhancing the accuracy, reliability, and admissibility of forensic evidence.

Understanding the Reproducibility Crisis: Foundational Principles and Sources of Variability in Forensic Techniques

Defining Inter-laboratory Reproducibility and its Impact on Justice and Forensic Science Validity

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Inter-laboratory Reproducibility Issues

Q1: Our lab's results consistently differ from collaborating laboratories when analyzing the same evidence samples. What is the most common root cause and how can we diagnose it?

A: The most frequent root cause is divergent analytical protocols across laboratories [1]. To diagnose this:

- Systematically compare all methodology: Don't just confirm the main technique (e.g., GC×GC–MS); compare every detail from sample preparation and chemical pretreatment to data processing parameters [1] [2].

- Conduct a cross-lab comparison: Use a set of identical, homogenous reference materials. Have each lab analyze them using their standard protocol and then again using a strictly unified protocol [1].

- Isolate variables: Use a "divide-and-conquer" approach. Test one variable at a time, such as acid reaction temperature, baking procedures, or column types, to identify which specific step causes the discrepancy [3] [1].

Q2: How can we improve the consistency of our stable isotope analysis results for tooth enamel with external partners?

A: A 2025 study indicates that simplifying your protocol can significantly improve comparability [1]. Key steps include:

- Eliminate chemical pretreatment: Research shows that chemical pretreatment of enamel samples is largely unnecessary and may introduce inaccuracies. Using untreated samples can yield more comparable results [1].

- Standardize ancillary conditions: Implement strict controls for baking samples and vials to remove moisture before analysis, and standardize the acid reaction temperature, even if its impact appears minimal [1].

- Document and share: Create a detailed, step-by-step Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) that all partners must follow, leaving no room for interpretation.

Q3: What legal standards must a new analytical method meet before its results are admissible in court?

A: Courts require new methods to meet rigorous standards to ensure reliability. The specific standards vary by jurisdiction [2]:

- Daubert Standard (U.S. Federal Courts and many states): The method must be tested, peer-reviewed, have a known error rate, and be generally accepted in the relevant scientific community [2].

- Frye Standard (Some U.S. States): The technique must be "generally accepted" by the relevant scientific community [2].

- Federal Rule of Evidence 702: Expert testimony must be based on sufficient facts, reliable principles and methods, and the reliable application of those methods to the case [2].

- Mohan Criteria (Canada): Expert evidence must be relevant, necessary, absent any exclusionary rule, and presented by a qualified expert [2].

Experimental Protocols for Validating Forensic Methods

The following workflow outlines the critical path for developing a forensic method that is both analytically sound and legally admissible.

Table 1: Technology Readiness Levels (TRL) for Forensic GC×GC Applications (as of 2024) [2]

| Forensic Application | Technology Readiness Level (TRL 1-4) | Key Barriers to Advancement |

|---|---|---|

| Illicit Drug Analysis | TRL 3-4 | Requires more intra- and inter-laboratory validation and standardized methods. |

| Fingermark Residue Chemistry | TRL 3 | Needs further validation and established error rates for courtroom readiness. |

| Decomposition Odor Analysis | TRL 3-4 | Growing research base (>30 works), requires standardization for legal acceptance. |

| Oil Spill Tracing & Arson Investigations | TRL 3-4 | Higher number of studies, but must meet legal criteria for routine use. |

| Chemical, Biological, Nuclear,\nRadioactive (CBNR) Forensics | TRL 2-3 | Early proof-of-concept stages; requires significant validation. |

| Forensic Toxicology | TRL 2-3 | Needs more focused research and validation studies. |

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Inter-laboratory Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|

| Stable Isotope Reference Materials | Calibrate instruments and verify accuracy across different laboratories [1]. |

| Homogenous Faunal Tooth Enamel Samples | Provide a consistent, well-characterized material for cross-lab comparison studies [1]. |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) for Illicit Drugs | Ensure quantitative accuracy and comparability in drug chemistry analysis between labs [2]. |

| Standardized Ignitable Liquid Mixtures | Act as a control sample in arson investigation studies to align results from different labs [2]. |

| Modulators (for GC×GC) | Interface between primary and secondary columns, crucial for achieving reproducible, high-resolution separations [2]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the single most important factor in achieving inter-laboratory reproducibility? A: While several factors are critical, standardization is paramount. This involves creating and adhering to meticulously detailed, step-by-step protocols that leave no room for interpretation, from sample preparation to data analysis [1] [2].

Q2: Our method works perfectly in our lab. Why does it need inter-laboratory validation for legal purposes? A: Intra-lab success demonstrates technical feasibility (TRL 3-4). However, courts require evidence that the method is robust and reliable independent of a specific lab's environment, equipment, or personnel. Inter-lab validation proves general acceptance and helps establish a known error rate, which is a direct requirement of the Daubert Standard [2].

Q3: What is the difference between "general acceptance" under Frye and the "reliability" factors under Daubert? A: The Frye Standard focuses narrowly on whether the scientific community broadly accepts the method. The Daubert Standard gives judges a more active "gatekeeping" role, requiring them to assess specific factors like testing, peer review, error rates, and standards controlling the technique's operation. Effectively, Daubert demands a deeper proof of the method's foundational reliability [2].

Q4: How can we create a troubleshooting guide for our own laboratory techniques? A: Follow a structured process [3] [4]:

- Identify Common Scenarios: List frequent problems from service logs.

- Determine Root Cause: Ask "When did it start?" and "What changed?".

- Establish Resolution Paths: Create a flow of questions and steps, starting with the simplest solutions (e.g., "Is the software updated?") before moving to complex ones.

- Document and Share: Build a knowledge base of solutions for both customers and internal teams to ensure consistent application and reduce problem-solving time.

For researchers and scientists in drug development and forensic science, inter-laboratory reproducibility is a critical determinant of success. The inability to independently replicate experimental outcomes undermines scientific validity, delays therapeutic breakthroughs, and can compromise forensic investigations [5]. Contemporary research suffers from widespread reproducibility challenges, with a significant percentage of published results failing successful replication by independent laboratories [5]. These challenges stem from multiple interacting sources of variability, including protocol variations, equipment differences, operator variability, and fluctuating environmental conditions [5]. This technical support center provides systematic troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers identify, control, and mitigate these variability sources, thereby enhancing the reliability and reproducibility of their technical readiness level (TRL) research.

Variability in experimental outcomes arises from the complex interplay of equipment performance, protocol implementation, human factors, and environmental conditions. A systematic approach to analyzing these sources is fundamental to improving reproducibility.

Equipment Variability

Instrument calibration, performance characteristics, and maintenance schedules introduce significant variability. Different research organizations may use different equipment brands or configurations that can lead to conflicting results [5]. For example, in automated SEM-EDS mineral analysis, instrumental reproducibility must be rigorously tested to ensure observed variability reflects true sample differences rather than instrument artifacts [6]. Predictive maintenance systems can analyze equipment performance data to identify instruments developing problems that could affect experimental reproducibility [5].

Protocol Implementation

Variations in experimental protocols, including reagent preparation, timing specifications, and procedural sequences, represent a major reproducibility challenge [5]. Traditional documentation methods often fail to capture critical details with sufficient precision, leading to different interpretations across research teams [5]. Dynamic protocol optimization enables continuous improvement of experimental procedures based on accumulating evidence from multiple implementations [5].

Human Factors

Operator skill, technique, and interpretation of experimental procedures introduce another layer of variability [5]. Studies of forensic decision-making highlight the importance of understanding variation in examiner judgments, particularly in disciplines relying on human comparisons such as latent prints, handwriting, and cartridge case analysis [7]. Personalized training programs that adapt to individual learning styles while ensuring consistent competency standards can help mitigate this variability [5].

Environmental Conditions

Small variations in temperature, humidity, air quality, and other environmental factors can dramatically impact experimental results, particularly in sensitive forensic and pharmaceutical applications [5]. Modern AI-enhanced quality control systems can provide real-time monitoring of experimental conditions and automated detection of deviations that could compromise reproducibility [5].

Table: Primary Sources of Inter-laboratory Variability

| Variability Source | Impact on Reproducibility | Example Scenarios |

|---|---|---|

| Equipment Performance | Different instruments may yield systematically different measurements for identical samples | - Different SEM-EDS manufacturers showing varied mineral analysis results [6]- Equipment calibration drift over time |

| Protocol Interpretation | Varying implementation of procedures across laboratories | - Different reagent preparation methods- Timing variations in multi-step processes [5] |

| Operator Technique | Individual differences in skill, experience, and methodological approach | - Forensic examiners making different decisions on identical evidence samples [7]- Variations in manual pipetting techniques |

| Environmental Conditions | Fluctuations in laboratory environment affecting experimental systems | - Temperature-sensitive reactions producing different yields- Humidity affecting spectroscopic measurements |

Troubleshooting Guides: Systematic Approaches to Common Scenarios

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Equipment-Related Variability

Problem: Inconsistent results from the same type of instrument across different laboratories.

Systematic Approach:

- Understand the Problem: Document the exact nature of discrepancies. Are results systematically biased or randomly varied? When did the issue first appear?

- Isolate the Issue:

- Check calibration records and maintenance logs for all instruments

- Run standardized reference materials on all instruments

- Exchange operators between instruments to rule out human factors

- Monitor environmental conditions during testing

- Find a Fix or Workaround:

- Recalibrate instruments using traceable standards

- Implement predictive maintenance schedules [5]

- Develop instrument-specific correction factors

- Establish equipment performance baselines and control charts

Guide 2: Troubleshooting Protocol-Related Variability

Problem: Different laboratories implementing the same published protocol obtain different results.

Systematic Approach:

- Understand the Problem: Identify which specific protocol steps show the greatest variation in implementation. Gather detailed documentation from each laboratory.

- Isolate the Issue:

- Compare reagent sources, preparation methods, and storage conditions

- Analyze timing variations in multi-step procedures

- Review equipment settings and configurations

- Identify steps with ambiguous descriptions in the original protocol

- Find a Fix or Workaround:

Guide 3: Troubleshooting Human Factor Variability

Problem: Different operators within the same laboratory obtaining different results using identical protocols and equipment.

Systematic Approach:

- Understand the Problem: Document the specific techniques and interpretations where operators differ. Determine if variations are random or systematic to certain individuals.

- Isolate the Issue:

- Conduct blind testing with identical samples

- Review raw data recording methods

- Analyze decision-making patterns in subjective assessments

- Identify specific technical skills that vary between operators

- Find a Fix or Workaround:

- Implement standardized training with competency assessments [5]

- Develop decision aids for subjective interpretations

- Establish regular proficiency testing

- Create detailed guidance for technical techniques prone to variation

The following workflow illustrates the systematic troubleshooting process for addressing reproducibility issues:

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most critical factors affecting inter-laboratory reproducibility in forensic techniques? The most critical factors include: (1) protocol standardization with insufficient detail for precise implementation, (2) equipment performance differences between manufacturers and even between instruments of the same model, (3) operator technique and decision-making processes, particularly in subjective assessments, and (4) environmental conditions that are often inadequately controlled or monitored [5] [7] [6].

Q2: How can we determine if variability comes from our equipment or our protocols? Implement a systematic isolation approach: First, run standardized reference materials on your equipment to establish a performance baseline. If variability persists with standards, the issue likely involves equipment. Next, have multiple trained operators execute the same protocol on the same equipment. If variability appears here, focus on protocol interpretation and human factors. Finally, systematically vary one protocol parameter at a time while holding others constant to identify sensitive steps [5].

Q3: What statistical approaches are appropriate for analyzing reproducibility and repeatability data? For continuous outcomes, mixed-effects models can account for both intra-examiner (repeatability) and inter-examiner (reproducibility) variability while also examining examiner-sample interactions. For binary decisions, generalized linear mixed models can partition variance components across these same factors. These approaches allow joint inference about repeatability and reproducibility while utilizing both intra-laboratory and inter-laboratory data [7].

Q4: How can we improve protocol implementation across different laboratories? Implement AI-driven protocol standardization systems that create comprehensive protocols capturing critical details often overlooked in traditional documentation. These systems can analyze successful experimental procedures, identify key variables that influence outcomes, and generate protocols that specify precise conditions for all aspects of experimental implementation. Additionally, electronic protocol execution systems can guide researchers through standardized procedures while automatically documenting compliance [5].

Q5: What role do environmental conditions play in reproducibility, and how can we control them? Small variations in temperature, humidity, air quality, vibration, and electromagnetic interference can significantly impact sensitive instruments and biological materials. Implement continuous environmental monitoring with alert systems for deviations. Establish tolerances for each environmental parameter specific to your techniques. Use environmental control chambers for particularly sensitive procedures, and document all environmental conditions alongside experimental results [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Reproducibility

| Reagent/Material | Function | Reproducibility Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Standardized Reference Materials | Calibrate instruments and validate methods | Use traceable standards with certified values; monitor lot-to-lot variability |

| Cell Culture Media | Support growth of biological systems | Standardize formulation sources; document component lots; control preparation and storage conditions |

| Analytical Solvents | Sample preparation and analysis | Specify purity grades; control storage conditions; monitor for degradation and contamination |

| Enzymes and Proteins | Catalyze reactions and serve as targets | Document source, lot, and storage conditions; establish activity assays for qualification |

| Antibodies | Detect specific molecules in assays | Validate specificity and sensitivity for each application; document clonal information and lots |

| PCR Reagents | Amplify specific DNA sequences | Standardize master mix formulations; control freeze-thaw cycles; use standardized thermal cycling protocols |

| QCMR Calibration Standards | Validate automated mineral analysis | Use well-characterized mineral standards; establish acceptance criteria for instrument performance [6] |

The following diagram illustrates the relationships between primary variability sources and corresponding control strategies in inter-laboratory research:

Improving inter-laboratory reproducibility in forensic TRL research requires a systematic, multifaceted approach addressing equipment, protocols, human factors, and environmental conditions. By implementing the troubleshooting guides, FAQs, and control strategies outlined in this technical support center, researchers and drug development professionals can significantly enhance the reliability and reproducibility of their experimental outcomes. The integration of AI-driven protocol standardization, automated quality control systems, continuous environmental monitoring, and comprehensive training programs creates a robust framework for reproducibility that transcends individual laboratories [5]. This systematic approach to analyzing and controlling variability sources ultimately strengthens scientific validity, accelerates drug development, and enhances the reliability of forensic techniques across the research continuum.

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This technical support resource addresses common challenges in stable isotope analysis, specifically focusing on methodological pitfalls that impact inter-laboratory reproducibility. The guidance is framed within broader research to enhance the Technology Readiness Level (TRL) of forensic isotopic techniques by improving their reliability and acceptance in legal contexts [2].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is there significant variability in isotope delta values for the same sample between different laboratories? Variability often stems from methodological heterogeneity, particularly differences in sample preparation protocols. A key study demonstrated that the practice of chemical pretreatment of tooth enamel samples created systematic differences between laboratories, while untreated samples showed much better comparability [1]. Other factors include a lack of standardized reaction temperatures and moisture control before analysis.

Q2: Is chemical pretreatment always necessary for tooth enamel samples prior to stable isotope analysis? No, findings indicate that chemical pretreatment is largely unnecessary for tooth enamel and may actually compromise the accuracy of stable isotope analyses. Skipping this step can improve inter-laboratory comparability [1].

Q3: What are the critical control points in the isotope analysis workflow to ensure data reliability? The entire workflow, from extraction to detection, requires control. Key points include [8] [9]:

- DNA/Protein Extraction: Ensuring complete removal of PCR inhibitors and preventing ethanol carryover.

- Quantification: Using accurately calibrated instruments and preventing sample evaporation.

- Amplification: Employing calibrated pipettes and thoroughly mixing reagents to avoid allelic dropouts.

- Separation/Detection: Using correct dye sets and high-quality, non-degraded formamide.

Q4: How can our laboratory demonstrate the reliability of our isotopic data for legal proceedings? For evidence to be admissible in court, the analytical method must meet legal standards for reliability. This includes demonstrating that the technique has been tested, has a known error rate, has been peer-reviewed, and is generally accepted in the scientific community (the Daubert Standard). Implementing rigorous quality assurance/quality control (QA/QC) protocols and participating in inter-laboratory comparisons are critical steps toward this goal [2].

Troubleshooting Guide for Isotope Analysis

Problem: Systematic Inter-Laboratory Bias in δ¹³C and δ¹⁸O Values

Background Stable isotope analysis of tooth enamel carbonate is a powerful tool for reconstructing diet and migration. However, the existence of numerous sample preparation protocols undermines the comparability of data across different studies and laboratories [1].

Experimental Protocol from Key Study A systematic inter-laboratory comparison was conducted to identify sources of bias [1]:

- Samples: Ten "modern" faunal teeth were used.

- Subsampling: Enamel powder subsamples were taken.

- Variable Testing:

- Chemical Pretreatment: Subsets of subsamples were subjected to common chemical pretreatment protocols, while others were left untreated.

- Acid Reaction Temperature: The temperature for sample acidification was standardized and non-standardized.

- Baking: The effect of baking samples and vials to remove ambient moisture before analysis was evaluated.

- Analysis: All samples were analyzed for δ¹³C and δ¹⁸O in two different laboratories.

Quantitative Results of Methodological Variations The following table summarizes the impact of different protocol variables on the comparability of isotope delta values between two laboratories:

| Protocol Variable | Impact on Inter-Laboratory Comparability | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Pretreatment | Introduced systematic differences [1]. | Omit chemical pretreatment for tooth enamel [1]. |

| No Pretreatment | Differences were smaller or negligible [1]. | Adopt as standard protocol for enamel. |

| Baking Samples | Improved comparability under certain lab conditions [1]. | Implement baking as a routine moisture-control step. |

| Acid Reaction Temperature | Appeared to have little-to-no impact on comparability [1]. | Not a primary focus for standardization. |

Solutions & Best Practices Based on the experimental findings, the following actions are recommended to minimize systematic bias:

- Eliminate Chemical Pretreatment: For tooth enamel samples, avoid chemical pretreatment protocols to prevent the introduction of systematic error [1].

- Implement Baking: Incorporate a baking step to remove moisture before analysis, which was shown to improve the agreement between laboratories [1].

- Adopt Standardized Protocols: Laboratories should collaboratively agree upon and adopt a common, simplified workflow for specific sample types to enhance reproducibility.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details key materials and their functions in isotope analysis and related forensic techniques.

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Tooth Enamel Samples | The primary biomineral used for measuring δ¹³C and δ¹⁸O for paleodietary and migration studies [1]. |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Well-characterized materials used for calibration and to ensure data accuracy and traceability in geochemical and isotopic analysis [9]. |

| Isotope-Labeled Compounds (e.g., D₂O, H₂¹⁸O) | Used as diagnostic tools in kinetic isotope effect (KIE) studies and for elemental tracing to pinpoint reaction pathways and mechanisms [10]. |

| Deionized Formamide | A high-purity solvent essential for proper DNA separation and detection in capillary electrophoresis; degraded formamide causes peak broadening and reduced signal intensity in STR analysis [8]. |

| PowerQuant System | A commercial kit used to accurately quantify DNA concentration and assess sample quality (e.g., degradation) before proceeding with amplification steps [8]. |

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Diagrams

Optimal Enamel Isotope Analysis Workflow

The Role of Cognitive Bias and Organizational Culture in Forensic Decision-Making

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Inter-Laboratory Reproducibility

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Our laboratory's results show significant variability when analyzing the same evidence across different operators. What steps can we take to improve consistency?

Answer: Implement standardized protocols and cross-operator validation. According to recent research, using uniform method parameters significantly increases the reproducibility of mass spectra across laboratories [11]. Key actions include:

- Establishing prescribed instrumental parameters for all operators

- Implementing regular proficiency testing using standardized sample sets

- Utilizing control samples to monitor inter-operator variability

- Conducting routine cross-validation sessions between team members

FAQ 2: How can we minimize the impact of contextual information on our forensic analyses?

Answer: Adopt information management protocols like Linear Sequential Unmasking (LSU). This approach controls the sequence and timing of information flow to practitioners, ensuring they receive necessary analytical information while minimizing exposure to potentially biasing contextual details [12]. Practical steps include:

- Utilizing case managers to screen case-related information before dissemination

- Documenting what information was received and when

- Implementing blind verification procedures where possible

- Requesting that evidence submitters avoid including potentially influencing context

FAQ 3: Our laboratory struggles with maintaining consistent conclusions for physical fit examinations. Are there standardized methods we can implement?

Answer: Yes, recent interlaboratory studies have demonstrated successful implementation of standardized methods for physical fit examinations. One study involving 38 practitioners from 23 laboratories achieved 99% accuracy in duct tape physical fit examinations using a novel method with standardized qualitative descriptors and quantitative metrics [13]. Key components include:

- Using standardized documentation protocols

- Implementing edge similarity score (ESS) as a quantitative metric

- Providing comprehensive training on the standardized method

- Establishing consensus criteria for evaluation outcomes

FAQ 4: What organizational culture factors most significantly impact forensic reproducibility?

Answer: Research indicates that flexible, collaborative cultures support more reproducible outcomes. Specifically:

- Clan cultures centered on cooperation and teamwork foster strong interpersonal relationships and knowledge sharing [14]

- Adhocracy cultures that encourage innovation and adaptability help laboratories implement new standardized methods [14]

- Market cultures focused on performance metrics can drive consistency but may create excessive pressure [14]

- Hierarchical cultures emphasizing strict protocols can ensure standardization but may limit adaptability [14]

Experimental Protocols for Reproducibility Assessment

Protocol 1: Interlaboratory Reproducibility Assessment for AI-MS Systems

This protocol is adapted from a recent interlaboratory study on ambient ionization mass spectrometry (AI-MS) for seized drug analysis [11].

Materials:

- Standardized solution set (21 solutions including single-compound and multi-compound mixtures)

- Controlled sample introduction apparatus

- Temperature and humidity monitoring equipment

- Standardized data collection templates

Methodology:

- Preparation: Distribute identical solution kits to all participating laboratories

- Analysis: Have each operator analyze all solutions in triplicate across four separate measurement sessions

- Data Collection: Record ambient temperature, humidity, and specific instrumental parameters for each session

- Comparison: Calculate pairwise cosine similarity between mass spectra from different operators and laboratories

- Analysis: Identify sources of variability including operator technique, instrumental configuration, and environmental factors

Quality Control:

- Implement positive and negative controls in each session

- Monitor for carryover from mass calibrants

- Regular cleaning of mass spectrometer inlets

- Document any deviations from standard protocols

Protocol 2: Physical Fit Examination Standardization

Based on interlaboratory studies of duct tape physical fit examinations [13].

Materials:

- Standardized sample sets with known fits and non-fits

- Digital documentation equipment

- Standardized scoring sheets

- Reference materials for comparison

Methodology:

- Blinding: Ensure examiners are blinded to the ground truth of sample pairs

- Examination: Follow systematic bin-by-bin examination protocol

- Documentation: Record observations using standardized qualitative descriptors

- Scoring: Calculate Edge Similarity Score (ESS) using established metrics

- Conclusion: Report conclusions based on predetermined criteria

Table 1: Interlaboratory Study Performance Metrics

| Study Focus | Participants | Accuracy Rate | Key Improvement Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| AI-MS Reproducibility [11] | 35 operators from 17 laboratories | High similarity scores with uniform parameters | Standardized instrumental methods, controlled sample introduction |

| Duct Tape Physical Fits (Study 1) [13] | 38 practitioners from 23 laboratories | 95% overall accuracy | Standardized qualitative descriptors, quantitative metrics |

| Duct Tape Physical Fits (Study 2) [13] | Same participants as Study 1 | 99% overall accuracy | Refined instructions, enhanced training, improved reporting tools |

| Cognitive Bias Mitigation [12] | Forensic practitioners | Not quantified | Linear Sequential Unmasking, blind verification, evidence lineups |

Table 2: Organizational Culture Types and Impact on Forensic reproducibility

| Culture Type | Key Characteristics | Impact on Forensic Reproducibility |

|---|---|---|

| Clan Culture [14] | Cooperation, teamwork, mentoring | Enhances knowledge sharing and consistency through strong interpersonal relationships |

| Market Culture [14] | Competition, goal achievement, performance metrics | Drives consistency through measurable outcomes but may encourage rushing |

| Adhocracy Culture [14] | Innovation, adaptability, entrepreneurial spirit | Supports implementation of new standardized methods but may introduce variability |

| Hierarchical Culture [14] | Control, structure, standardization, protocols | Ensures strict protocol adherence but may limit adaptive problem-solving |

Workflow Diagrams

Cognitive Bias Mitigation Workflow: This diagram illustrates the sequential protocol for minimizing cognitive bias in forensic decision-making, incorporating Linear Sequential Unmasking and blind verification [12] [15].

Interlaboratory Reproducibility Assessment: This workflow shows the systematic approach for assessing and improving reproducibility across forensic laboratories [11] [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Reproducibility Studies

| Item | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Standardized Solution Sets [11] | Provides consistent reference materials across laboratories | Interlaboratory mass spectrometry studies using 21 solutions including single-compound and multi-compound mixtures |

| Control Samples [11] | Monitors instrumental performance and operator technique | Positive and negative controls in AI-MS reproducibility assessment |

| Physical Fit Examination Kits [13] | Standardizes physical evidence comparisons | Duct tape physical fit studies with known fits and non-fits |

| Environmental Monitoring Equipment [11] | Tracks laboratory conditions that may affect results | Thermometers and hygrometers to monitor temperature and humidity during AI-MS analysis |

| Standardized Documentation Templates [12] [13] | Ensures consistent recording of methods and observations | Edge Similarity Score (ESS) sheets for physical fit examinations; case documentation logs |

| Information Management Protocols [12] [15] | Controls flow of potentially biasing information | Linear Sequential Unmasking (LSU) worksheets; case manager guidelines |

The National Institute of Justice (NIJ) Forensic Science Strategic Research Plan, 2022-2026 establishes a comprehensive framework designed to address critical challenges in forensic science, with inter-laboratory reproducibility standing as a central pillar for advancing reliability and validity across the discipline [16]. This technical support center operationalizes the Plan's strategic priorities by providing targeted troubleshooting guidance for researchers and scientists working to implement reproducible, legally defensible forensic techniques. The integration of Technology Readiness Levels (TRL) into forensic method development ensures that research advances from basic proof-of-concept to court-ready applications, meeting stringent legal standards including the Daubert Standard and Federal Rule of Evidence 702 [2]. The following sections provide practical experimental protocols, troubleshooting guides, and resource recommendations to support the implementation of this Strategic Research Plan within your laboratory.

Core Strategic Priorities & Technical Implementation

The NIJ's Research Plan is structured around five strategic priorities that collectively address the entire forensic science ecosystem—from basic research to courtroom implementation [16] [17]. The table below summarizes these priorities and their relevance to improving inter-laboratory reproducibility.

Table 1: NIJ Strategic Priorities and Reproducibility Applications

| Strategic Priority | Technical Focus Areas | Reproducibility Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Advance Applied R&D | Novel technologies, automated tools, standard criteria [16] [17] | Method optimization, workflow standardization, instrument calibration protocols |

| Support Foundational Research | Validity/reliability testing, decision analysis, error rate quantification [16] | Black box studies, white box studies, interlaboratory comparison designs [16] |

| Maximize R&D Impact | Research dissemination, implementation support, practice adoption [16] | Best practice guides, validation studies, proficiency test development |

| Cultivate Workforce | Training, competency assessment, continuing education [16] | Proficiency testing, competency standards, collaborative research networks |

| Coordinate Community | Information sharing, partnership engagement, needs assessment [16] | Standard reference materials, data sharing platforms, method harmonization |

Foundational Research for Reproducibility

Foundational research provides the scientific basis for evaluating and improving reproducibility across laboratories. The NIJ emphasizes validity and reliability testing through controlled studies that identify sources of error and establish methodological boundaries [16].

Diagram 1: Foundational Research Framework for Reproducibility

Technical Support Center: FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: Method Validation & Legal Admissibility

Q1: What legal standards must new forensic methods meet before implementation in casework?

New analytical methods for evidence analysis must adhere to standards laid out by the legal system, including the Frye Standard, Daubert Standard, and Federal Rule of Evidence 702 in the United States and the Mohan Criteria in Canada [2]. The Daubert Standard, followed by federal courts, requires assessment of four key factors: (1) whether the technique can be and has been tested, (2) whether the technique has been peer-reviewed and published, (3) the known or potential rate of error, and (4) whether the technique is generally accepted in the relevant scientific community [2].

Q2: How can our laboratory accelerate Technology Readiness Level (TRL) advancement for novel methods?

Advancing TRL requires systematic validation across multiple laboratories. Current research on comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography (GC×GC) demonstrates a framework for TRL assessment, categorizing methods across levels 1-4 based on technical maturity [2]. To advance TRL, focus on intra-laboratory validation, interlaboratory studies, error rate analysis, and standardization through organizations like the Organization of Scientific Area Committees for Forensic Science (OSAC) [2].

Q3: What strategies improve interlaboratory reproducibility for complex instrumental analyses?

Key strategies include: developing standard reference materials, establishing uniform data processing protocols, implementing cross-lab proficiency testing, and creating detailed method transfer documentation [16] [18]. For techniques like GC×GC, standardized modulation parameters, consistent column selections, and harmonized data analysis approaches significantly improve interlaboratory comparability [2].

Q4: How can we address discordant results in interlaboratory comparison studies?

Discordant results often reveal "dark uncertainty" - unrecognized sources of measurement variation [18]. Systematic approaches include: comparative analysis of sample preparation protocols, instrument calibration procedures, data interpretation criteria, and environmental conditions. The DerSimonian-Laird procedure and hierarchical Bayesian methods provide statistical frameworks for analyzing interlaboratory data and identifying sources of variation [18].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

Table 2: Troubleshooting Forensic Method Development

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| High variability in interlaboratory results | Uncalibrated equipment, divergent protocols, analyst interpretation differences [18] | Implement standardized reference materials, establish quantitative interpretation thresholds | Pre-collaborative harmonization studies, detailed SOPs with examples |

| Method meets analytical but not legal standards | Insufficient error rate data, limited peer-review, no general acceptance [2] | Conduct black-box studies, pursue multi-lab validation, submit for publication | Early engagement with legal stakeholders, systematic error rate documentation |

| Poor transfer of complex methods between laboratories | Incomplete technical documentation, platform-specific parameters, varying skill levels | Create detailed transfer packages, conduct hands-on training, implement competency assessment | Develop instrument-agnostic methods, establish core competency standards |

| Inconsistent results with trace evidence | Sample collection variability, environmental degradation, instrumental detection limits [16] | Standardize collection protocols, establish chain of custody procedures, implement QC samples | Environmental monitoring, validated storage conditions, blank controls |

Experimental Protocols for Reproducibility Research

Protocol: Interlaboratory Comparison Study Design

Objective: To assess the reproducibility of a forensic method across multiple laboratories and instrument platforms.

Materials:

- Homogenized reference material with known properties

- Standard operating procedure (SOP) document

- Data reporting template

- Validated quality control samples

Methodology:

- Pre-study Harmonization: Conduct training session for all participating laboratories to ensure consistent understanding and application of the method [18].

- Sample Distribution: Distribute identical aliquots of reference material to all participants with explicit storage and handling instructions.

- Data Collection: Each laboratory analyzes the material following the provided SOP under their normal working conditions.

- Result Analysis: Collect all data using standardized reporting templates. Apply statistical models (e.g., DerSimonian-Laird procedure, hierarchical Bayesian methods) to assess interlaboratory variance [18].

- Follow-up Investigation: For outliers, conduct root cause analysis through additional testing and protocol review.

Data Interpretation: Calculate consensus values and assess "dark uncertainty" - the difference between stated measurement uncertainties and observed variability between laboratories [18].

Protocol: Technology Readiness Level Assessment for Forensic Methods

Objective: To systematically evaluate the maturity of a forensic technique for implementation in casework.

Diagram 2: Technology Readiness Level Assessment Pathway

Assessment Criteria:

- TRL 1-3 (Basic Research): Peer-reviewed publications establishing fundamental principles [2].

- TRL 4-5 (Method Development): Single-laboratory validation with defined error rates and controlled conditions.

- TRL 6-7 (Interlaboratory Testing): Multi-laboratory validation studies demonstrating reproducibility [18].

- TRL 8-9 (Implementation): Casework application, proficiency testing, and general acceptance in relevant scientific community [2].

Documentation Requirements: For each TRL level, maintain records of experimental data, validation studies, error rate calculations, and peer-review evaluations.

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Reproducibility Studies

| Material/Reagent | Technical Function | Reproducibility Application |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials | Calibration standards with documented uncertainty | Instrument qualification, method validation, cross-lab harmonization [18] |

| Quality Control Materials | Stable, homogeneous materials with characterized properties | Within-lab precision monitoring, between-lab comparison studies [18] |

| Standard Operating Procedure Templates | Detailed methodological documentation | Protocol harmonization, training standardization, technical transfer packages |

| Data Reporting Templates | Standardized formats for result documentation | Systematic data collection, meta-analysis, statistical comparison |

| Proficiency Test Materials | Blind samples for competency assessment | Laboratory performance evaluation, method robustness assessment [16] |

| Statistical Analysis Packages | Software for interlaboratory data analysis | DerSimonian-Laird procedure, hierarchical Bayesian methods, consensus value calculation [18] |

The NIJ Forensic Science Strategic Research Plan provides a comprehensive roadmap for advancing inter-laboratory reproducibility through strategic research priorities and practical implementation frameworks [16]. By integrating Technology Readiness Level assessment with legally-admissible validation standards, forensic researchers can systematically advance methods from basic research to routine application [2]. The troubleshooting guides, experimental protocols, and resource recommendations provided in this technical support center offer practical tools for addressing common challenges in reproducibility studies. Continued focus on collaborative research networks, standardized materials, and workforce development will further strengthen the scientific foundations of forensic practice across the community of practice [16] [17].

Building Robust Methods: Standardized Protocols, Emerging Technologies, and TRL Integration

Developing and Implementing Standardized Operating Procedures (SOPs) Across Disciplines

Within the context of improving inter-laboratory reproducibility for forensic techniques in Technology Readiness Level (TRL) research, variability in protocol execution and instrument handling are significant sources of error. This technical support center provides standardized troubleshooting guides and FAQs to empower researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. By offering immediate, standardized solutions to common experimental and instrumental problems, this resource aims to minimize procedural drift and enhance the reliability and cross-laboratory comparability of research outcomes.

Core Troubleshooting Methodology

A structured approach to problem-solving is fundamental to maintaining reproducibility. The following three-phase methodology should be adopted for addressing any technical issue [3].

The Troubleshooting Process

Technical Troubleshooting Guides

Instrumentation and Data Acquisition Issues

Problem: Instrument fails to initialize or power on.

- Question: What are the observable signs when you attempt to power on the instrument?

- Investigation: Check all power connections at the instrument and the wall outlet. Verify that the outlet is functional by testing it with another device. Listen for any fan noise or look for indicator lights [19].

- Resolution: If no signs of power are present, ensure the main power switch on the instrument is engaged. If the problem persists, the issue may be with an internal component like the power supply unit, and professional service should be contacted.

Problem: Unrecognized USB device (e.g., data acquisition module).

- Question: Is this a device that was previously working on this computer?

- Investigation: Restart the computer. Try connecting the device to a different USB port. Test the USB device on another computer to rule out a hardware failure [19].

- Resolution: If the device works on another computer, update or reinstall the device drivers on the original computer. If it is not recognized on any computer, the USB device itself may be faulty.

Problem: Software application crashes or will not run.

- Question: When does the crash occur? Is there an associated error message?

- Investigation: Check the software's compatibility with your operating system. Restart the application and computer. Check for and install any available software updates, which often contain bug fixes [19].

- Resolution: If updates do not resolve the issue, reinstall the software. Check for other running applications that might be conflicting with the software.

Data and Analysis Issues

Problem: Inability to access shared data repositories or login credentials.

- Question: Are you unable to recall your password, or is your account locked?

- Investigation: Use the system's self-service password reset function, which typically sends a reset link via email. Check your spam folder if the email is not received [19].

- Resolution: If self-service is unavailable or the account is locked after multiple failed attempts, contact your IT helpdesk. They can verify your identity and reset your credentials [19].

Problem: Slow data processing or computer performance.

- Question: Is the performance slow for all tasks or only specific applications?

- Investigation: Close unnecessary applications and background processes. Check available disk space and free up space if it is nearly full. Run antivirus or anti-malware scans [19].

- Resolution: For analysis-heavy applications, ensure your computer meets the recommended system specifications. For persistent issues, consider hardware upgrades or consult with IT support.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Account and Access

- Q: How can I reset my password for the shared laboratory information management system (LIMS)?

- A: Use the "Forgot Password" link on the LIMS login page. You will receive instructions via your registered email. If you do not receive the email, check your junk or spam folder [20].

- Q: My account is locked. What should I do?

- A: Account lockouts typically occur after several failed login attempts. Please contact the IT helpdesk directly. They will verify your identity and unlock your account [19].

Data Management and Sharing

- Q: What is the SOP for naming raw data files to ensure traceability?

- A: Per our reproducibility SOP, all raw data files must be named using the convention:

YYYYMMDD_ResearcherInitials_InstrumentID_ExperimentID.ext. This ensures chronological sorting and unambiguous identification of the data source.

- A: Per our reproducibility SOP, all raw data files must be named using the convention:

- Q: How should I handle a situation where my experimental results deviate significantly from the established positive control?

- A: First, repeat the assay with the positive control to confirm the deviation. Then, systematically troubleshoot your protocol and reagents. Document all steps and observations meticulously. If the issue persists, consult the principal investigator and refer to the detailed troubleshooting guide for that specific assay in our knowledge base.

Experimental Protocols

- Q: What should I do if my negative control shows contamination or unexpected activity?

- A: Immediately halt all related experiments. The entire batch of reagents used in that assay session (e.g., buffers, water) may be compromised. Discard the affected reagents, prepare fresh ones using sterile techniques, and repeat the assay. This event must be documented in the laboratory deviation log.

- Q: The instrument calibration is failing. Can I proceed with my experiment?

- A: No. Do not proceed with data acquisition if calibration fails. First, repeat the calibration procedure as per the SOP. If it fails again, check the calibration standards for integrity and prepare fresh ones if needed. If the problem continues, label the instrument as "Out of Service" and report the issue to the lab manager.

Experimental Protocol for Inter-Laboratory Calibration Verification

Objective: To provide a standardized methodology for verifying the calibration and performance of a key instrument (e.g., a spectrophotometer) across multiple laboratories, ensuring data comparability.

Principle: The absorbance of a series of certified reference materials (e.g., potassium dichromate solutions) is measured and compared to established standard values. The linearity and accuracy of the response are used to assess instrument performance.

Workflow for Calibration Verification

Methodology:

- Reagent Preparation: Prepare a dilution series of a certified potassium dichromate solution in 0.005 M sulfuric acid. Concentrations should span the dynamic range of the instrument (e.g., 0, 20, 40, 60, 80, 100 mg/L).

- Instrument Preparation: Power on the spectrophotometer and allow it to warm up for the time specified in the manufacturer's SOP (typically 30 minutes). Zero the instrument using the blank solution (0 mg/L).

- Data Acquisition: Measure the absorbance of each standard solution in triplicate at 350 nm. Use a matched set of cuvettes for all measurements.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the average absorbance for each concentration. Plot the average absorbance versus concentration and perform linear regression analysis.

- Acceptance Criteria: The calibration curve must have a correlation coefficient (R²) of ≥ 0.995. The slope should be within ±2% of the value established during the last successful inter-laboratory comparison.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following reagents are critical for the inter-laboratory calibration verification protocol and must be sourced and handled as specified to ensure reproducibility.

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Material | Function in Protocol | Specification & Handling |

|---|---|---|

| Potassium Dichromate (K₂Cr₂O₇) | Certified reference material for creating the calibration standard series. | ACS grade or higher, certified for spectrophotometry. Dry for 2 hours at 110°C before use. |

| Sulfuric Acid (H₂SO₄) | Used as the solvent for the potassium dichromate standards to maintain a stable pH. | ACS grade, low in UV absorbance. Prepare a 0.005 M solution using ultrapure water. |

| Ultrapure Water | Solvent for all reagent preparation; used for the blank and dilution series. | Type I grade (18.2 MΩ·cm at 25°C), tested to be free of particulates and UV-absorbing contaminants. |

| Spectrophotometric Cuvettes | Contain the sample for absorbance measurement. | Matched set, with a defined pathlength (e.g., 1 cm), and transparent at the wavelength of 350 nm. |

Data Presentation and Acceptance Criteria

Quantitative data from calibration and verification experiments must be evaluated against predefined criteria to determine the validity of an experimental run.

Table 2: Acceptance Criteria for Spectrophotometric Calibration Verification

| Parameter | Target Value | Acceptable Range | Corrective Action if Failed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation Coefficient (R²) | 1.000 | ≥ 0.995 | Check for pipetting errors, prepare fresh standard solutions, and clean cuvettes. |

| Slope of Calibration Curve | Established Reference Value | ± 2% of Reference Value | Verify instrument wavelength accuracy and perform a full manufacturer-recommended calibration. |

| Absorbance of Blank (Zero Standard) | 0.000 | < 0.010 | Ensure cuvettes are clean and the blank solution is prepared correctly. |

| % Relative Standard Deviation (RSD) of Triplicate Reads | 0.0% | ≤ 1.5% | Check for air bubbles in the cuvette and ensure the sample is homogenous. |

Leveraging Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning for Automated Analysis and Pattern Recognition

Technical Support Center

This support center provides troubleshooting guidance for researchers implementing AI and ML systems in forensic science laboratories. The following guides address common technical challenges to improve the reliability and reproducibility of your experiments.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Our AI model for pattern recognition performs well on training data but generalizes poorly to new forensic samples. What diagnostic steps should we take?

This indicates potential overfitting, a common challenge in forensic AI applications. Follow this systematic isolation procedure [3]:

- Step 1: Simplify the Input - Reduce complexity by testing with minimal feature sets. For image-based models, try grayscale inputs before full color spectrums [3].

- Step 2: Cross-Validation - Implement k-fold cross-validation (typically k=5 or k=10) to ensure performance consistency across data subsets [21].

- Step 3: Data Augmentation Check - Verify your augmentation methods (rotation, scaling, noise addition) reflect real-world forensic sample variations.

- Step 4: Compare to Baseline - Test against a traditional algorithm (e.g., k-NN) to establish performance benchmarks [21].

Recommended Protocol: Begin with a controlled dataset of known provenance, systematically introducing variability while monitoring performance degradation points.

Q2: How can we validate that our AI system meets forensic reliability standards before operational deployment?

Validation should progress through structured Technology Readiness Levels (TRLs) [22] [23]:

- TRL 4-5 (Lab Validation): Conduct closed testing with historical case data with known outcomes [22] [24].

- TRL 6 (Relevant Environment): Test prototypes with simulated casework in controlled laboratory settings [23] [24].

- TRL 7 (Operational Environment): Implement parallel testing where AI and human examiners process identical samples independently [25].

Documentation Requirements: Maintain detailed audit trails of all user inputs, model parameters, and decision pathways to facilitate external review [25].

Q3: What strategies exist for prioritizing forensic evidence analysis using AI when facing resource constraints?

Implement a triaging system with these components [25]:

- Predictive Modeling: Use historical case data to estimate processing time based on evidence type, complexity, and required analyses [25].

- Evidence Utility Ranking: Apply machine learning to analyze past evidence types and outcomes, ranking incoming evidence by potential investigative value [25].

- Human Oversight: Maintain forensic examiner review of all AI-generated prioritization lists to prevent critical evidence misclassification [25].

Q4: How do we address the "black box" problem of complex neural networks in forensic applications where explainability is essential?

Adopt these technical approaches:

- Implement Hybrid Models: Combine deep learning (e.g., CNNs) with interpretable algorithms (e.g., k-NN) for specific sub-tasks [21].

- Attention Mechanisms: Utilize models that highlight regions of interest in images, providing visual explanations for decisions.

- Model Simplification: Start with simpler architectures like BPNNs before advancing to more complex CNNs, only when justified by performance gains [21].

Experimental Protocols for AI Implementation

Protocol 1: Cross-Laboratory Validation Framework

Objective: Establish standardized testing procedures to assess AI model performance across multiple forensic laboratories.

Materials:

- Reference dataset with ground truth annotations

- Standardized computing environment specifications

- Performance metrics framework (accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score)

Methodology:

- Dataset Partitioning: Divide reference dataset into training (60%), validation (20%), and testing (20%) subsets [21].

- Environment Configuration: Implement identical software environments (Python version, library versions) across participating laboratories.

- Blinded Testing: Conduct analyses on blinded samples to prevent unconscious bias.

- Statistical Analysis: Calculate inter-rater reliability using Fleiss' kappa for categorical data and intraclass correlation coefficients for continuous measurements.

Success Criteria: >0.8 interlaboratory concordance rate for categorical classifications; <5% coefficient of variation for continuous measurements.

Protocol 2: Technology Readiness Assessment for Forensic AI Systems

Objective: Systematically evaluate maturity of AI technologies for forensic applications using TRL framework [22] [23] [24].

Materials:

- TRL assessment checklist

- Domain-specific test scenarios

- Performance benchmarking tools

Methodology:

- TRL 3-4 (Proof of Concept): Validate core algorithms using controlled laboratory data [22] [24].

- TRL 5-6 (Relevant Environment): Test with historical case data resembling operational conditions [23] [24].

- TRL 7-8 (Operational Environment): Conduct prospective studies with current casework alongside traditional methods [23] [24].

- TRL 9 (Implementation): Deploy for routine use with continuous monitoring and validation [22].

Table: Technology Readiness Levels for Forensic AI Systems

| TRL | Description | Validation Requirements | Forensic Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1-2 | Basic principles observed and formulated | Literature review, theoretical research | Concept for AI-based diatoms classification [21] |

| 3-4 | Experimental proof of concept | Laboratory testing with controlled samples | Algorithm development for heat-exposed bone analysis [21] |

| 5-6 | Component validation in relevant environment | Testing with historical case data | Prototype for postmortem interval estimation [21] |

| 7-8 | System prototype in operational environment | Parallel testing with human examiners | AI-assisted human identification from radiographs [21] |

| 9 | Actual system proven in operational environment | Full deployment with quality assurance | Automated pattern recognition in high-volume digital evidence [22] |

Workflow Visualization

AI-Assisted Forensic Analysis Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Components for AI-Forensic Research

| Research Component | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) | Image pattern recognition for morphological analysis | Identification of unique bone features for human identification [21] |

| k-Nearest Neighbor (k-NN) | Classification based on feature similarity | Categorization of diatoms in drowning diagnosis [21] |

| Backpropagation Neural Networks (BPNNs) | Training complex models through error minimization | Age estimation from skeletal and dental remains [21] |

| Robust Object Detection Frameworks | Reliable detection under challenging conditions | Recognition of injuries in postmortem imaging [21] |

| Audit Trail Documentation | Tracking AI decision processes for legal proceedings | Recording user inputs and model parameters for courtroom testimony [25] |

| Cross-Validation Datasets | Assessing model generalizability and preventing overfitting | Interlaboratory reproducibility testing with shared reference materials [21] |

TRL Advancement Decision Pathway

The Critical Role of Reference Materials, Databases, and Control Samples

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the core concepts of repeatability and reproducibility in interlaboratory studies?

In the context of interlaboratory studies, repeatability refers to the precision of a test method when the measurements are taken under the same conditions—same operator, same apparatus, same laboratory, and short intervals of time. Reproducibility, on the other hand, refers to the precision of the test method when measurements are taken under different conditions—different operators, different apparatus, and different laboratories [26]. These metrics are essential for understanding the reliability and variability of forensic techniques.

2. Why are 'black-box' studies recommended for forensic disciplines like latent prints and firearms examination?

'Black-box' studies are designed to estimate the reliability and validity of decisions made by forensic examiners. In a typical black-box study, examiners judge samples of evidence as they would in practice, while the ground truth about the samples is known by the study designers [7]. This design allows for the collection of data from repeated assessments by different examiners (reproducibility) and repeated assessments by the same examiner on the same evidence samples (repeatability), providing a robust framework for evaluating the soundness of a forensic method [7] [27].

3. Our laboratory is planning an interlaboratory study. What is the standard practice for such an endeavor?

ASTM E691 is the standard practice for conducting an interlaboratory study to determine the precision of a test method [26]. The process involves three key phases:

- Planning: Forming a task group, designing the study, selecting participating laboratories and test materials, and writing the study protocol.

- Testing: Preparing and distributing materials, liaising with laboratories, and collecting the test result data.

- Analysis: Using statistical techniques to analyze the data for consistency, investigate unusual values, and calculate numerical measures of precision (repeatability and reproducibility) [26].

4. What guidelines can be used to establish the scientific validity of a forensic feature-comparison method?

Inspired by established scientific frameworks, a guidelines approach can be used to evaluate forensic methods. The four key guidelines are [27]:

- Plausibility: The scientific soundness of the underlying theory.

- The soundness of the research design and methods: This encompasses construct and external validity, ensuring the study actually tests what it claims to and that the results are generalizable.

- Intersubjective testability: The ability for the method and results to be replicated and reproduced by different researchers.

- A valid methodology to reason from group data to statements about individual cases: The capacity to move from population-level data to source-specific claims.

5. What are common pitfalls affecting interlaboratory reproducibility in chemical analysis, and how can they be mitigated?

Research on ancient bronze analysis found that results for certain elements (like Pb, Sb, Bi, Ag) showed poorer reproducibility compared to others (like Cu, Sn, Fe, Ni) [28]. This highlights that data variation is element-specific. Mitigation strategies include [28]:

- Using certified reference materials (CRMs) that are matrix-matched to the samples being tested.

- Regularly performing method validation and participating in interlaboratory comparison programs.

- Understanding that legacy data from different laboratories may have inherent variations that must be accounted for in comparative studies.

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Interlaboratory Reproducibility Issues

| Problem | Possible Root Cause | Diagnostic Questions | Recommended Solution & Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| High variability in results for a specific analyte. | Inconsistent calibration or use of non-traceable reference materials [28]. | 1. Are calibration curves verified with independent standards?2. Are the reference materials certified and from an accredited provider? | Implement a rigorous calibration verification protocol using certified reference materials (CRMs). Validate by analyzing a control sample and confirming the result falls within its certified uncertainty range. |

| Systematic bias in results across multiple laboratories. | Divergent sample preparation methodologies or data interpretation criteria [27]. | 1. Is the test method protocol sufficiently detailed and unambiguous?2. Are all laboratories using the same type and brand of critical reagents? | Review and standardize the experimental protocol. Provide detailed written procedures and training. Validate by conducting a round-robin test with a homogeneous control sample and statistically evaluating the results for bias. |

| Inconsistent findings in forensic pattern comparison (e.g., fingerprints, toolmarks). | Lack of objective criteria and subjective decision-making by examiners [7] [27]. | 1. Are examiners using a standardized set of features for comparison?2. What is the error rate of the method as established by black-box studies? | Introduce objective feature-based algorithms where possible. Establish standardized reporting language. Validate by participating in black-box studies to estimate the method's repeatability and reproducibility and establish error rates [7]. |

| Failure to replicate a published study's findings. | Inadequate reporting of experimental details or unrecognized environmental factors [27]. | 1. Does the published method specify all critical reagents and equipment models?2. Have you attempted to contact the original authors for clarification? | Meticulously document all deviations from the published protocol. Control laboratory environmental conditions (e.g., temperature, humidity). Validate by successfully reproducing the study using a control sample with a known outcome. |

Experimental Workflow for an Interlaboratory Study

The following diagram outlines the key phases and decision points for conducting a standardized interlaboratory study, based on guidelines like ASTM E691 [26].

Data Analysis Workflow for Reproducibility Studies

This diagram illustrates the statistical process for analyzing data from reproducibility and repeatability studies, which allows for joint inference using both intra-examiner and inter-examiner data [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Provides a known quantity of an analyte with a certified level of uncertainty. Used for method validation, calibration, and quality control to ensure accuracy and traceability [28]. |

| Control Samples | A sample with a known property or outcome, used to monitor the performance of a test method. Positive and negative controls are essential for detecting systematic errors and confirming the method is working as intended. |

| Standardized Protocols | A detailed, step-by-step written procedure for conducting a test method. Critical for ensuring consistency within and between laboratories, which is a foundation for reproducibility [26]. |

| Statistical Software for ILS | Software capable of performing the complex calculations outlined in standards like ASTM E691. Used to compute repeatability and reproducibility standard deviations and other precision measures from interlaboratory data [26]. |

This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs to assist researchers in implementing and validating new forensic methods, with a focus on improving inter-laboratory reproducibility and Technology Readiness Level (TRL) research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key legal and scientific criteria a new analytical method must meet for courtroom admissibility? New analytical methods for evidence analysis must meet rigorous standards set by legal systems. In the United States, the Daubert Standard guides the admissibility of expert testimony and assesses whether: (1) the technique can be and has been tested; (2) it has been subjected to peer review and publication; (3) it has a known or potential error rate; and (4) it is generally accepted in the relevant scientific community. In Canada, the Mohan Criteria require that evidence is relevant, necessary, absent of any exclusionary rule, and presented by a properly qualified expert [2].

Q2: What is a Technology Readiness Level (TRL) and why is it important for forensic method development? A Technology Readiness Scale (Levels 1 to 4) is used to characterize the advancement of research in specific application areas. Achieving a higher TRL is crucial for the adoption of new methods into forensic laboratories, as it demonstrates that the method has undergone sufficient validation and standardization to be considered reliable and fit-for-purpose for routine casework [2].

Q3: What are the primary sources of error in physical fit examinations, and how can they be minimized? Studies on duct tape physical fits demonstrate that while analysts generally have high accuracy rates, errors can occur. Potential sources of error and bias can be minimized by using systematic methods for examination and documentation, such as tools that generate quantitative similarity scores, and by employing linear sequential unmasking to reduce cognitive bias [29].

Q4: How can inter-laboratory studies improve the reproducibility of a forensic technique? Inter-laboratory studies are a critical step in evaluating new methodologies. They involve multiple practitioners from different labs analyzing the same samples to establish the method's utility, validity, reliability, and reproducibility. These studies help identify the capabilities and limitations of a method and are fundamental for developing consensus protocols that can be widely implemented by the scientific community [29].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inconsistent Results in Inter-Laboratory Comparisons

Problem: Different laboratories applying the same method obtain conflicting results when analyzing identical samples, threatening the method's reproducibility and legal admissibility.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

- Confirm Method Protocol Adherence: Ensure all participating labs are using a identical, step-by-step protocol. Even minor deviations in sample preparation, instrument settings, or interpretation criteria can significantly impact results [29].

- Standardize Reporting Criteria: Implement quantitative and objective reporting metrics. For example, in duct tape physical fit studies, using a calculated Edge Similarity Score (ESS) reduces subjective judgment and improves inter-participant agreement [29].

- Review Participant Training: Inconsistent results can stem from varying levels of familiarity with the new method. Provide comprehensive, hands-on training for all practitioners and use mock samples to assess competency before formal inter-laboratory studies begin [29].

Preventative Measures:

- Develop a detailed, written methodology with visual aids and examples.

- Establish a central coordination body to manage the study design, distribute materials, and analyze results [29].

Issue 2: Low Technology Readiness Level (TRL) for a Novel GC×GC-MS Method

Problem: Your comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC×GC-MS) method for analyzing complex mixtures (e.g., illicit drugs or decomposition odor) is effective in a research setting but is not yet ready for implementation in a routine forensic laboratory.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

- Conduct Intra-Laboratory Validation: Before involving other labs, rigorously test the method within your own lab. This includes determining its precision, accuracy, sensitivity, and robustness under varying conditions [2].

- Perform Inter-Laboratory Validation: Organize or participate in a formal inter-laboratory study. This is essential for demonstrating that the method produces reproducible results across different instruments, operators, and environments [2] [29].

- Establish a Known Error Rate: Work with statisticians to analyze validation data and calculate a method's error rate. A known and acceptable error rate is a critical requirement for meeting the Daubert Standard for courtroom evidence [2].

Preventative Measures:

- Design validation studies with legal admissibility requirements (e.g., Daubert, Mohan) in mind from the outset.

- Focus on standardizing the method and documenting standard operating procedures (SOPs) early in the development process [2].

Issue 3: Difficulty in Demonstrating "General Acceptance" for a New Technique

Problem: A novel analytical technique, while scientifically sound, faces skepticism because it is not yet "generally accepted" in the forensic science community.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

- Publish in Peer-Reviewed Journals: Submission and acceptance of research by independent peer reviewers is a key factor in establishing scientific acceptance and is directly cited in the Daubert Standard [2].

- Present at Scientific Conferences: Sharing findings at professional conferences (e.g., American Academy of Forensic Sciences) exposes the method to the wider community and fosters discourse and acceptance.

- Collaborate Broadly: Engage with multiple independent research groups and forensic laboratories. Widespread use and validation by different teams are powerful evidence of general acceptance [2] [29].

Preventative Measures:

- Engage with the relevant scientific community early and often.

- Actively participate in and contribute to organizations, such as the Organization of Scientific Area Committees (OSAC), that work to develop consensus standards for forensic science [29].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Table: Key Performance Metrics from Duct Tape Physical Fit Inter-Laboratory Studies

This table summarizes quantitative data from studies evaluating a systematic method for examining duct tape physical fits, demonstrating the method's reliability and reproducibility across multiple practitioners [29].

| Study Metric | Value / Finding | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Accuracy | Generally high accuracy rates were reported [29]. | Demonstrates the method is effective and reliable. |