Advancing Forensic DNA Mixture Analysis: Protocols, Probabilistic Genotyping, and Emerging Technologies

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern protocols for forensic DNA mixture analysis, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Advancing Forensic DNA Mixture Analysis: Protocols, Probabilistic Genotyping, and Emerging Technologies

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern protocols for forensic DNA mixture analysis, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles, from the challenges of interpreting complex multi-contributor samples to the standards governing their validation. The scope extends to detailed methodological applications of probabilistic genotyping software and cutting-edge single-cell techniques, alongside practical troubleshooting for low-template and degraded DNA. A critical evaluation of validation frameworks and comparative performance of emerging next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies equips professionals to implement robust, reliable analysis pipelines in both forensic and clinical research contexts.

The Foundation of DNA Mixture Analysis: Understanding Complex Profiles and Regulatory Standards

The interpretation of DNA mixtures, defined as biological samples containing DNA from two or more individuals, represents one of the most complex challenges in modern forensic science [1] [2]. As forensic methodologies have advanced, laboratories are increasingly processing challenging evidence samples that contain low quantities of DNA, are partially degraded, or contain contributions from three or more individuals [3] [2]. These complex mixtures introduce interpretational difficulties including allele drop-out, where alleles from a contributor fail to be detected; allele sharing among contributors, leading to "allele stacking"; and the challenge of differentiating true alleles from polymerase chain reaction (PCR) artifacts such as stutter peaks [3] [2]. The accurate resolution of these mixtures is paramount, as the statistical evidence derived from them must withstand legal scrutiny in courtroom proceedings [3] [4].

This document outlines the core principles, analytical thresholds, and statistical frameworks for interpreting complex forensic DNA mixtures within the context of established forensic DNA panels research. The protocols detailed herein are designed to ensure that mixture interpretation yields reliable, reproducible, and defensible results.

Core Interpretation Challenges and Analytical Thresholds

The analysis of mixed DNA samples is compounded by several technical artifacts and biological phenomena that must be systematically addressed. Table 1 summarizes the primary challenges and the corresponding analytical considerations required for accurate interpretation.

Table 1: Key Challenges in Forensic DNA Mixture Interpretation

| Challenge | Description | Interpretative Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Allele Drop-out | Failure to detect alleles from a true contributor, often due to low DNA quantity or degradation [3]. | Use of stochastic thresholds; loci with potential drop-out may be omitted from Combined Probability of Inclusion (CPI) calculations [3] [5]. |

| Allele Sharing | The same allele is contributed by multiple individuals, reducing the observed number of alleles [3] [5]. | The maximum allele count may underestimate the true number of contributors; particularly problematic in 4-person mixtures [5]. |

| Stutter Artifacts | Peaks typically one repeat unit smaller than the true allele, generated during PCR amplification [2]. | Peaks must be differentiated from true alleles of minor contributors; peak height ratios and thresholds are used [2]. |

| Low Template DNA (LT-DNA) | Very low amounts of DNA (<200 pg) lead to increased stochastic effects [2] [5]. | Requires allowing for stochastic effects like drop-out and "drop-in" (contamination) [2]. Replication can help [5]. |

| Determining Contributor Number | Estimating the number of individuals who contributed to the sample [5]. | The maximum allele count per locus provides a minimum number. Probabilistic methods can improve accuracy, especially for 3-4 person mixtures [5]. |

Quantitative Data Analysis and Statistical Frameworks

Once the DNA profile has been generated and the mixture identified, the weight of the evidence is quantified using statistical methods. The two predominant approaches are the Combined Probability of Inclusion/Exclusion (CPI/CPE) and the Likelihood Ratio (LR) [3] [6]. Table 2 compares the quantitative data analysis methods employed in DNA mixture interpretation.

Table 2: Statistical Methods for Evaluating DNA Mixture Evidence

| Method | Principle | Application Context | Formula/Output | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combined Probability of Inclusion (CPI) | Calculates the proportion of a population that would be included as potential contributors to the mixture based on the observed alleles [3] [4]. | Most common method in the U.S. and many other regions for less complex mixtures. Not suited for mixtures where allele drop-out is probable [3] [4]. | ( CPI = \prod (p1 + p2 + \cdots + pn)^2 ) where ( pi ) are the frequencies of observed alleles [3]. | ||

| Likelihood Ratio (LR) | Compares the probability of the evidence under two competing hypotheses (e.g., prosecution vs. defense) [2] [6]. | Preferred method for complex mixtures (low-template, >2 contributors) via probabilistic genotyping software [3] [2]. | ( LR = \frac{Pr(E | H_p)}{Pr(E | H_d)} ) providing a statement such as "The evidence is X times more likely if the DNA originated from the suspect and an unknown individual than if it originated from two unknown individuals" [6]. |

| Random Match Probability (RMP) | Estimates the rarity of a deduced single-source profile in a population [6]. | Applied when contributors to a mixture can be fully separated or deduced into individual profiles [5]. | Expressed as "the probability of randomly selecting an unrelated individual with this profile is 1 in X" [6]. |

Experimental Protocol for Mixture Interpretation Using CPI/CPE

The following protocol, adapted from the guidelines detailed by [3] and [4], provides a step-by-step methodology for the interpretation and statistical evaluation of DNA mixture evidence using the CPI/CPE approach.

Protocol Workflow

Materials and Equipment

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Standard Reference Materials (SRM 2391d) | NIST-provided 2-person female:male (3:1 ratio) mixture for validation and quality control [1]. |

| Research Grade Test Materials (RGTM 10235) | NIST-provided multi-person mixtures (e.g., 90:10, 20:20:60 ratios) to assess DNA typing performance and software tools [1]. |

| Commercial STR Kits (e.g., PowerPlex,AmpFlSTR NGM) | Multiplex systems for co-amplification of 15-16 highly variable Short Tandem Repeat (STR) loci plus amelogenin [2]. |

| Automated Extraction Systems | Systems (e.g., PrepFiler Express with Automate Express) for rapid, consistent DNA extraction, minimizing human error [7]. |

| Quantification Kits (e.g., Plexor HY) | For quantifying total human and male DNA in complex forensic samples, informing downstream analysis strategy [2]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Profile Assessment and Mixture Identification [3] [2]

- Examine the electropherogram (EPG) data for the presence of more than two allelic peaks at multiple loci.

- Evaluate peak height balance. Significant imbalance at a heterozygous locus can indicate a mixture, even if only two peaks are present.

- Identify and account for artifacts, particularly stutter peaks, using laboratory-validated stutter percentage thresholds.

Estimate the Number of Contributors (NOC) [5]

- Apply the maximum allele count method: the locus with the highest number of observable alleles (after accounting for stutter and tri-allelic patterns) indicates the minimum number of contributors.

- For example, a profile with 5 alleles at one or more loci suggests a minimum of 3 contributors.

- Note that this method can underestimate the true number, especially in 4-person mixtures with significant allele sharing [5].

Mixture Deconvolution and Comparison [3] [6]

- Using peak heights, attempt to separate the mixture into major and minor components where possible.

- Compare the mixed profile to reference profiles from known individuals (e.g., the victim). If a known profile is included, "subtract" their allelic contributions to deduce the profile of the unknown contributor(s).

- Determine if a person of interest (POI) can be included or excluded as a potential contributor.

Locus Qualification for CPI Calculation [3] [4]

- This is a critical step. Examine each locus to determine if allele drop-out is a reasonable possibility based on low peak heights observed at other loci.

- Disqualify any locus from the CPI calculation where allele drop-out is likely. These loci may still be used for exclusionary purposes.

Statistical Evaluation via CPI [3] [4]

- For loci qualified in the previous step, calculate the Probability of Inclusion (PI). The PI is the square of the sum of the frequencies for all observed alleles at that locus: ( PI = (p1 + p2 + \cdots + pn)^2 ), where ( pi ) represents the frequency of the i-th allele in the relevant population database.

- The Combined Probability of Inclusion (CPI) is the product of the individual PIs across all qualified loci: ( CPI = \prod PI_{locus} ).

- The Combined Probability of Exclusion (CPE) is the complement: ( CPE = 1 - CPI ). The CPE represents the proportion of the population that would be excluded as contributors to the observed mixture.

Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

The field of forensic DNA mixture analysis is evolving rapidly with the integration of new technologies that enhance the interpretation of complex samples.

- Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): NGS technologies provide deeper sequence information, enabling better resolution of mixture components and the analysis of a wider range of genetic markers [1] [7]. NIST is developing and making publicly available NGS data for complex three-, four-, and five-person mixtures to support method development [1].

- Probabilistic Genotyping and Artificial Intelligence (AI): Sophisticated software systems using probabilistic genotyping models and AI are becoming central to interpreting complex mixtures where traditional methods like CPI are inadequate [3] [7]. These systems use statistical models and Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithms to compute Likelihood Ratios (LRs) that coherently account for stochastic effects like drop-out and drop-in [1] [3].

- Rapid DNA and Mobile Platforms: Portable devices that allow for automated DNA extraction and profile generation in the field are emerging, though they are currently used in specific, time-sensitive contexts rather than daily laboratory casework [7].

ANSI/ASB Standard 020: Standard for Validation Studies of DNA Mixtures, and Development and Verification of a Laboratory's Mixture Interpretation Protocol establishes foundational requirements for forensic DNA laboratories conducting mixture analysis [8]. This standard provides the framework for designing internal validation studies for mixed DNA samples and developing interpretation protocols based on validation data [8]. It applies broadly across DNA testing technologies including STR testing, DNA sequencing, SNP testing, and haplotype testing where DNA mixtures may be encountered [8].

The standard addresses the critical challenge of interpreting complex DNA mixtures, which occur when evidence contains DNA from multiple individuals [9]. These mixtures present particular interpretive difficulties, as studies have demonstrated that different laboratories or analysts within the same lab may reach different conclusions when evaluating the same DNA mixture [9]. Standard 020 aims to mitigate this variability by ensuring laboratories establish validated, reliable protocols before applying them to casework.

Core Requirements of ANSI/ASB Standard 020

Key Component Requirements

Table 1: Core Components of ANSI/ASB Standard 020

| Component | Description | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Validation Studies | Studies to characterize performance of methods and analytical thresholds [9] | Establish scientific foundation for protocol development |

| Protocol Development | Creation of laboratory-specific interpretation procedures based on validation data [8] | Ensure methods are tailored to and supported by empirical data |

| Protocol Verification | Testing protocols with samples different from validation studies [9] | Demonstrate consistent, reliable conclusions in practice |

| Scope Limitation | Restricting interpretation to mixture types within validated bounds [9] | Prevent over-application of methods beyond their demonstrated reliability |

Implementation Workflow

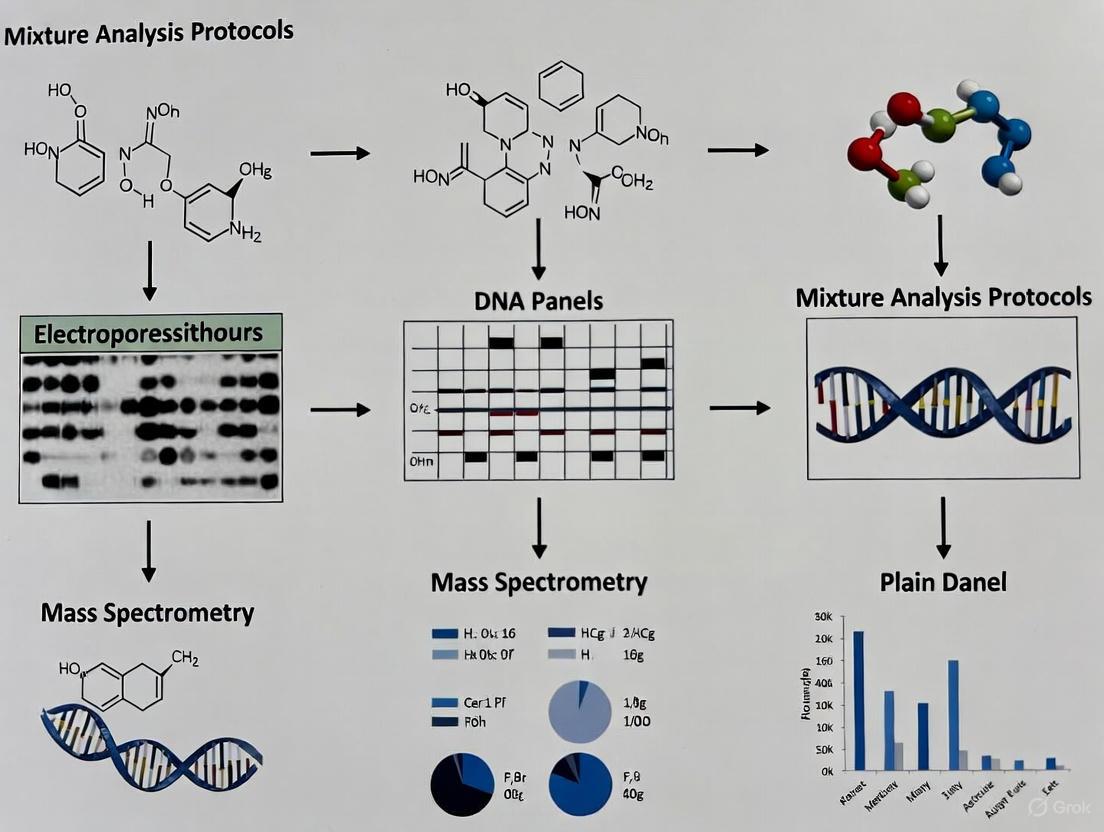

The following diagram illustrates the sequential process for implementing Standard 020 requirements within a forensic laboratory:

OSAC Registry Framework and Requirements

OSAC Registry Structure and Content

The OSAC Registry serves as a repository of selected published and proposed standards for forensic science, containing minimum requirements, best practices, standard protocols, and terminology to promote valid, reliable, and reproducible forensic results [10]. The Registry includes two distinct types of standards:

- SDO-published standards: Documents that have completed the consensus process of an external Standards Development Organization and been approved by OSAC for Registry placement [10]

- OSAC Proposed Standards: Drafts created by OSAC and provided to an SDO for further development and publication, available for implementation while undergoing the formal SDO process [10]

As of recent 2025 data, the OSAC Registry contains approximately 245 standards, with 162 SDO-published and 83 OSAC Proposed standards representing over 20 forensic science disciplines [10]. This growing repository reflects the dynamic nature of forensic standards development, with new standards regularly added and existing standards revised or replaced [11].

Standards Development and Maintenance Process

The development and maintenance of standards on the OSAC Registry follows a rigorous process with multiple stakeholders:

The standards landscape is "quite dynamic," with new standards consistently added to the Registry and existing standards routinely replaced as new editions are published due to cyclical review and occasional off-cycle updates [11]. This process requires ongoing attention from implementing laboratories to maintain current practices.

Experimental Protocol: Validation Study for DNA Mixture Interpretation

Validation Study Design and Execution

This protocol outlines the experimental requirements for validating DNA mixture interpretation methods according to ANSI/ASB Standard 020.

4.1.1 Study Design Parameters

- Define the scope of mixture types to be validated (number of contributors, mixture ratios, degradation states, etc.)

- Establish sample size with statistical justification for each mixture type

- Include negative and positive controls in all experimental runs

- Incorporate known challenging mixture types that may be encountered in casework

4.1.2 Data Collection and Analysis

- Perform replicate testing to assess reproducibility

- Document all analytical thresholds and criteria for inclusion/exclusion

- Record quantitative and qualitative data for all profiling systems used

- Assess sensitivity and specificity of the interpretation method

4.1.3 Interpretation Guidelines Development

- Establish specific criteria for allele calling, peak height thresholds, and stutter filtering

- Define parameters for probabilistic genotyping software if utilized

- Create decision trees for complex mixture resolution

- Document all statistical approaches and confidence measures

Protocol Verification Methodology

Verification requires testing the laboratory-developed protocol with samples different from those used in the initial validation studies [9]. This critical step confirms that the protocol generates consistent and reliable conclusions when applied to independent samples.

4.2.1 Verification Sample Selection

- Utilize samples with different genetic profiles than validation samples

- Include mixture types spanning the validated scope but with different proportions

- Incorporate casework-like samples when possible

- Blind testing is recommended to minimize bias

4.2.2 Assessment Criteria

- Demonstrate inter-analyst consistency in interpretation

- Verify reproducibility across multiple instrument runs

- Confirm that results meet established reliability thresholds

- Document any discrepancies and establish resolution procedures

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for DNA Mixture Analysis

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for DNA Mixture Analysis Validation

| Reagent/Material | Function in Validation | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Characterized Reference DNA | Provides quantified, standardized DNA for controlled mixture preparation | Essential for creating validation samples with known contributor ratios and concentrations |

| Commercial STR Multiplex Kits | Amplifies target loci for DNA profiling | Select kits appropriate for sample type; validate with mixture studies specific to each kit |

| Quantitation Standards | Measures DNA concentration and quality prior to amplification | Critical for establishing input DNA parameters for reliable mixture interpretation |

| Probabilistic Genotyping Software | Provides statistical framework for complex mixture interpretation | Requires extensive validation studies; document all parameters and thresholds |

| Inhibitor Spiking Solutions | Assesses method robustness to common PCR inhibitors | Tests protocol performance with compromised samples typical in forensic casework |

| Degraded DNA Controls | Evaluates method performance with fragmented DNA | Determines limitations of interpretation protocols with suboptimal samples |

Implementation Considerations for Forensic Laboratories

Integration with Quality Assurance Systems

Successful implementation of ANSI/ASB Standard 020 requires integration with existing laboratory quality assurance frameworks. Laboratories must document compliance with standard requirements while maintaining flexibility for method-specific validation approaches. This includes establishing documentation systems that track validation parameters, protocol versions, and verification results for audit purposes.

Scope Management and Limitations

A critical requirement of Standard 020 is that "labs not interpret DNA mixtures that go beyond what they have validated and verified" [9]. For example, if a laboratory has only validated its protocol for up to three-person mixtures, it must not attempt to interpret four-person mixtures in casework. This necessitates careful definition of validation boundaries and clear protocols for when additional validation is required.

Relationship to Other Standards

ANSI/ASB Standard 020 complements but does not replace other forensic standards. Laboratories must still comply with the FBI's DNA Quality Assurance Standards for laboratories participating in the national DNA database system [9]. Additionally, the standard builds upon earlier guidelines published by the Scientific Working Group on DNA Analysis Methods (SWGDAM), providing more specific requirements rather than general recommendations [9].

The analysis of complex DNA mixtures, a frequent challenge in forensic casework, has long been constrained by the limitations of traditional technologies. For decades, capillary electrophoresis (CE) has been the gold standard for forensic DNA profiling, relying on the detection of Short Tandem Repeats (STRs) [12]. However, the evolution of Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) is fundamentally expanding the scope and power of genetic data analysis. This Application Note details how the transition from CE to NGS overcomes historical limitations in mixture analysis, providing researchers and drug development professionals with enhanced resolution for deciphering complex biological samples. We frame this technological progression within the context of developing more robust mixture analysis protocols for forensic DNA panels.

Technological Comparison: CE versus NGS

The core difference between CE and NGS lies in the type of genetic marker analyzed and the method of detection. CE separates DNA fragments by size, interpreting STRs based on their length [12]. In contrast, NGS determines the actual nucleotide sequence, simultaneously assaying STRs, Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs), and other markers [12] [13]. This fundamental distinction leads to significant differences in data output and application, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Capillary Electrophoresis and Next-Generation Sequencing

| Feature | Capillary Electrophoresis (CE) | Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Markers | Short Tandem Repeats (STRs) [12] | STRs, Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs), and more [12] [13] |

| Readable Sequence | No (indirect sizing via length) | Yes (direct nucleotide sequencing) [12] |

| Multiplexing Capability | Low (~20-30 STRs) [12] | Very High (e.g., 10,230 SNPs in a single kit) [12] |

| Mutation Rate | Relatively high [12] | Low [12] |

| Amplicon Size | Relatively large (can be >200 bp) [12] | Typically small (e.g., majority <150 bp) [12] |

| Typical Application | STR profiling for direct matching and kinship (up to 1st/2nd degree) [12] | Extended kinship analysis (up to ~5th degree), biogeographical ancestry, phenotype [12] |

| Data Output per Sample | Low (fragment sizes for ~20-30 loci) | High (millions of sequence reads) [13] |

| Performance on Degraded DNA | Challenged due to large amplicon sizes [12] | Superior, due to shorter amplicons and higher sensitivity [12] |

Experimental Evidence: NGS Performance on Challenging Samples

Empirical studies demonstrate the superior performance of NGS on compromised samples, which are often encountered in forensic casework and biomedical research.

Analysis of Aged Skeletal Remains

A systematic comparison analyzed 83-year-old human skeletal remains using both CE (PowerPlex ESX 17 and Y23 Systems) and NGS (ForenSeq Kintelligence kit with the MiSeq FGx System) [12].

- NGS Success Rate: The NGS workflow generated viable genetic information for 18 out of 20 samples (90%). Of these, 16 had a sufficient number of SNPs (>8,000) to upload for kinship matching in the GEDmatch PRO database, with five samples generating a possible kinship association [12].

- CE Success Rate: The CE-based analysis was only successful for 9 out of the 20 samples (45%) when using a 5 RFU threshold, and for 14 samples (70%) with a more permissive 1 RFU threshold, which increases the risk of interpreting background noise [12].

This study concluded that the NGS/SNPs method provided viable investigative leads in samples that yielded no or incomplete profiles with the standard CE/STR method [12].

Detection of Clonal Gene Rearrangements in Lymphoma

In clinical diagnostics, a study on classic Hodgkin’s lymphoma compared CE and NGS for detecting immunoglobulin (IG) gene rearrangement, a key marker for clonality [14].

- CE Detection: Identified monoclonal rearrangements in 25% (5/20) of specimens [14].

- NGS Detection: Identified monoclonal rearrangements in 60% (12/20) of specimens [14].

The study attributed the higher sensitivity of NGS to its ability to provide precise sequence data, overcoming interpretive challenges like abnormal peaks that can occur with CE [14].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: NGS Analysis of Human Remains Using the ForenSeq Kintelligence Kit

This protocol is adapted from the methodology used to analyze aged skeletal remains [12].

1. DNA Extraction:

- Sample Type: Bone samples (e.g., femur, pars petrosum) or teeth.

- Method: Use a specialized DNA extraction kit for bone samples [15]. For powdered bone, a silica-based method or organic extraction is recommended to purify DNA and inhibit PCR inhibitors.

2. DNA Quantification:

- Method: Use a DNA quantification kit compatible with degraded DNA and capable of measuring human-specific content (e.g., Quantifiler Trio DNA Quantification Kit) [15].

- Criterion: Proceed with samples meeting a minimum concentration threshold (e.g., ≥ 0.010 ng/μL, with an optimal concentration of ≥ 0.04 ng/μL) [12].

3. Library Preparation (ForenSeq Kintelligence Kit):

- Process: The kit uses a single-tube multiplex PCR to simultaneously amplify 10,230 SNPs.

- Input DNA: Use 25 μL of DNA extract per manufacturer's recommendations [12].

- Goal: To create a sequencing library enriched for targeted SNPs.

4. Sequencing:

- Instrument: Perform sequencing on the MiSeq FGx Sequencing System.

- Data Output: The system generates millions of paired-end reads.

5. Data Analysis:

- Software: Analyze data using the ForenSeq Universal Analysis Software (UAS).

- Kinship Analysis: The UAS employs an Identity-by-Descent (IBD) segment-based approach, outputting potential relationships based on the amount of shared DNA (centimorgans, cM) between two individuals [12].

- Upload: Data can be made compatible with genetic genealogy databases like GEDmatch PRO for extended kinship searching [12].

Protocol: STR Analysis via Capillary Electrophoresis

This standard protocol is based on forensic laboratory procedures [15].

1. DNA Extraction:

- Sample Type: Varies (bloodstains, buccal swabs, bone, etc.).

- Method: Use robotic systems (e.g., EZ1 Advanced XL, QIAcube) or manual organic extraction depending on the sample type [15].

2. DNA Quantification:

- Method: Use a fluorescent dye-based quantification method (e.g., Quantifiler Trio DNA Quantification Kit) to determine total human DNA concentration [15].

3. PCR Amplification:

- Kits: Use commercially available multiplex STR kits (e.g., PowerPlex Fusion System, PowerPlex ESX 17 System) [12] [15].

- Thermocycler: Perform amplification on a validated thermal cycler (e.g., Mastercycler X50s) [15].

- Cycle Number: Typically 28-34 cycles.

4. Capillary Electrophoresis:

- Instrument: Run amplified products on a genetic analyzer (e.g., ABI 3500xL Genetic Analyzer) [15].

- Separation: DNA fragments are injected into a capillary filled with polymer and separated by size under an electric field.

- Detection: A laser detects fluorescently labeled DNA fragments as they pass a detection window.

5. Data Analysis:

- Software: Analyze raw data using specialized software (e.g., GeneMarker) [15].

- Interpretation: Alleles are called based on their size compared to an internal size standard. Profiles are interpreted by trained analysts, often with the aid of probabilistic genotyping software (e.g., STRmix) for complex mixtures [15].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the core procedural differences between the CE and NGS workflows, highlighting the key advantage of sequence-based analysis in NGS.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The following table details key materials and reagents essential for implementing the CE and NGS workflows in a research or developmental setting.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Forensic Genetic Analysis

| Item | Function | Example Products / Kits |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits (Bone) | Purifies DNA from challenging, calcified tissues while removing PCR inhibitors. | QIAamp DNA Investigator Kit, Promega Bone Extraction Kits [15]. |

| DNA Quantification Kits | Accurately measures the concentration of human-specific DNA, critical for input into downstream assays. | Quantifiler Trio DNA Quantification Kit [15]. |

| CE STR Multiplex Kits | Amplifies a standardized set of STR loci in a single PCR reaction for length-based profiling. | PowerPlex Fusion System, PowerPlex ESX 17 System [12] [15]. |

| NGS Forensic Panels | Enables targeted amplification of thousands of forensic markers (SNPs/STRs) for multiplexed sequencing. | ForenSeq Kintelligence Kit (Verogen) [12]. |

| NGS Sequencer | Instrument platform for performing massively parallel sequencing of prepared libraries. | MiSeq FGx Sequencing System [12]. |

| Genetic Analyzer (CE) | Instrument for capillary electrophoresis, separating fluorescently labeled DNA fragments by size. | ABI 3500 Series Genetic Analyzers [14] [15]. |

| Probabilistic Genotyping Software | Advanced software to interpret complex DNA mixtures by calculating likelihood ratios. | STRmix [15]. |

| NGS Data Analysis Suite | Software for processing sequencing data, aligning reads, and performing kinship/population statistics. | ForenSeq Universal Analysis Software (UAS) [12]. |

Probabilistic Genotyping, Likelihood Ratios, and the Continuous Model Framework

Probabilistic genotyping (PG) represents a fundamental shift in the interpretation of forensic DNA mixtures. Unlike traditional binary methods, probabilistic genotyping software utilizes continuous quantitative data from DNA profiles to compute a Likelihood Ratio (LR), which assesses the strength of evidence under competing propositions [16] [17]. This framework is particularly vital for interpreting complex mixtures involving multiple contributors, low-template DNA, or unbalanced mixtures, which pose significant challenges for conventional methods [18] [19].

The continuous model framework retains and utilizes more information from the electropherogram (epg), including peak heights and their quantitative properties, rather than reducing data to simple presence/absence thresholds [17]. This approach allows for a more nuanced and statistically robust evaluation of evidential weight, which is communicated to the trier-of-fact through the Likelihood Ratio [20]. The LR is a statistic that compares the probability of observing the evidence under two alternative hypotheses: the prosecution's hypothesis (Hp) that the person of interest contributed to the sample, and the defense's hypothesis (Hd) that the DNA originated from unknown, unrelated individuals [17] [20]. An LR greater than 1 supports the prosecution's proposition, while an LR less than 1 supports the defense's proposition [17].

Technical Framework of Probabilistic Genotyping

Model Components and Variability

Continuous interpretation methods employ probabilistic models to account for various electropherogram phenomena. Table 1 summarizes the key components and their treatment in different model implementations.

Table 1: Key Model Components in Continuous Probabilistic Genotyping Systems

| Model Component | Function | Examples of Model Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Allele Peak Height Distribution | Models the expected signal intensity for true alleles | Normal distribution [17]; Gamma distribution [17]; Log ratio of observed to expected peak heights [17] |

| Stutter Artifact Modeling | Accounts for PCR amplification artifacts (non-allelic peaks) | Reverse stutter (one repeat unit shorter) [17]; Forward stutter (one repeat unit larger) [17] |

| Noise/Drop-in Modeling | Accounts for background noise and sporadic contaminant alleles | Not accounted for [17]; Fixed probability [17]; Function of observed peak height [17]; Normal distribution [17] |

| Mixture Ratio Treatment | Specifies contributor proportions in the mixture | Assumed constant across all loci [17]; Allowed to vary by locus [17] |

Different probabilistic genotyping systems implement these model components differently, which can lead to non-negligible differences in the reported LR [17]. A study examining four variants of a continuous model found inter-model variability in the associated verbal expression of the LR in 32 of 195 profiles tested. Crucially, in 11 profiles, the LR straddled the critical threshold of 1, changing from LR > 1 (supporting Hp) to LR < 1 (supporting Hd) depending on the model used [17] [21]. This highlights the importance of validating specific software and establishing its reliability bounds.

The Likelihood Ratio in Practice

The LR provides a measure of how much more likely it is to obtain the evidence if the person of interest is a contributor versus if they are not [20]. It is critical to understand what the LR does and does not represent. Common misconceptions include:

- The LR is not the probability that the person of interest is the donor.

- It is not correct to argue that "there is only a 1-in-[LR] chance that someone other than the defendant contributed the DNA" [20].

- An LR > 1 does not equate to definite inclusion, nor does LR < 1 equate to definite exclusion [20].

The magnitude of the LR determines the strength of support. Laboratories often use verbal scales to communicate this strength (e.g., "limited," "moderate," or "very strong" support), though the specific scales are not standardized [20]. For instance, a statistic of 1.661 quadrillion provides vastly stronger corroboration of inclusion than an LR just above a laboratory's reporting threshold of 1,000 [20].

Advanced Applications and Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Mixture Analysis Using a Microhaplotype (MH) MPS Panel with UMIs

The following protocol details a methodology for analyzing complex DNA mixtures using a microhaplotype MPS panel incorporating Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs), as described in recent research [18].

1. Sample Preparation and DNA Extraction

- Collect biological samples (e.g., oral swabs) with appropriate ethical approval and informed consent [18].

- Extract genomic DNA using a commercial kit (e.g., QIAamp DNA Blood Kit).

- Quantify the DNA using a fluorometric method (e.g., Qubit Fluorometer).

2. Library Construction with UMI Integration

- Use a multiplex PCR to amplify a 105-plex MH panel. Each MH is selected for high polymorphism (average Ae value of 6.9) and short length (average 119 bp) to facilitate analysis of degraded DNA [18].

- During library construction, attach Unique Molecular Identifiers (8–12 bp sequences) to each original DNA fragment. This step is critical, as UMIs allow for the bioinformatic distinction of true alleles from sequencing errors by tracking amplicons that originate from the same original molecule [18].

- Perform library normalization, though note that this step can distort the relationship between the original DNA template amount and the final sequencing read count [18].

3. Massively Parallel Sequencing

- Pool the prepared libraries and sequence on an appropriate MPS platform (e.g., Illumina systems) to obtain paired-end reads [18].

4. Bioinformatic Analysis and Data Interpretation

- Read Mapping and Alignment: Map raw reads to the human reference genome using tools like bowtie2 and discard unmapped or partially mapped reads [19].

- Error Correction and UMI Deduplication:

- Retain only paired-end reads where both reads report an identical allele sequence for a given locus to minimize false alleles [19].

- Group reads with identical UMIs into "UID families." The presence of multiple UMI families supporting the same allele confirms its authenticity [18].

- For mixture proportion estimation, use UMI families with more than 10 members to achieve stable molecular count (Mx) values across loci, which improves correlation with the actual DNA template mixture ratio [18].

- Mixture Deconvolution: The high polymorphism and density of the MH markers allow for the detection of minor contributors in unbalanced, multi-contributor, and even kinship-involved mixtures [18].

Performance Data of the MH-MPS Panel

Table 2: Performance Metrics of the 105-plex MH-MPS Panel with UMIs

| Parameter | Performance Result | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Total Discrimination Power (TDP) | 1–7.0819E-134 | Panel-wide [18] |

| Sensitivity | ~70–80 loci detected | DNA input as low as 0.009765625 ng [18] |

| Minor Allele Detection | >65% of minor alleles distinguishable | 1 ng DNA with a frequency of 0.5% in 2- to 4-person mixtures [18] |

| Key Strength | Effective detection in unbalanced, multi-contributor, and kinship mixtures | Validated across various mixture scenarios [18] |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for MPS-Based Mixture Analysis

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example Product / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Multiplex Microhaplotype Panel | Simultaneous amplification of multiple, highly polymorphic loci for high-resolution mixture deconvolution. | 105-plex MH panel (Avg. Ae=6.9, Avg. length=119 bp) [18] |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Short, random nucleotide sequences added to DNA fragments to tag and track original molecules, enabling distinction of true alleles from PCR/sequencing errors. | 8–12 bp sequences incorporated during library prep [18] |

| MPS Library Prep Kit | Prepares DNA amplicons for sequencing by adding platform-specific adapters and sample indices. | MGIEasy Universal DNA Library Prep Set [19] |

| High-Sensitivity DNA Quantitation Kit | Accurately measures low concentrations of genomic DNA and library constructs prior to sequencing. | Fluorometer-based kits (e.g., Qubit assays) [18] [19] |

| Bioinformatic Tools for UMI Processing | Software for UMI deduplication, error correction, and haplotype calling from raw sequencing data. | Custom pipelines involving bowtie2 for alignment and UID family grouping [18] [19] |

Workflow and Logical Framework Visualization

Logical Framework for DNA Evidence Interpretation

MPS Workflow with UMI for Mixture Analysis

The adoption of probabilistic genotyping and the continuous model framework represents the modern standard for the interpretation of forensic DNA mixtures. These methods leverage more quantitative data than threshold-based systems, providing a robust statistical assessment through the Likelihood Ratio [16] [17]. The implementation of these models, however, requires careful consideration, as differences in underlying assumptions can impact the computed LR [17] [21]. Emerging technologies, including MPS-based microhaplotype panels and Unique Molecular Identifiers, are pushing the boundaries of mixture analysis, enabling the deconvolution of increasingly complex mixtures that were previously intractable [18] [19]. For researchers and practitioners, a thorough understanding of the model components, their potential variability, and the correct interpretation of the LR is essential for ensuring that this powerful evidence is presented accurately and fairly within the justice system [20].

Methodological Deep Dive: From Probabilistic Genotyping to End-to-End Single-Cell Solutions

The interpretation of mixed DNA evidence, which contains genetic material from two or more individuals, presents one of the most significant challenges in modern forensic science. Traditional binary methods, which make yes/no decisions about genotype inclusion, often prove inadequate for complex mixtures involving multiple contributors, low-template DNA, or degraded samples [22]. Probabilistic genotyping (PG) has emerged as a powerful computational solution to these challenges, enabling forensic scientists to evaluate DNA evidence through a statistical framework that accounts for the uncertainties inherent in the analysis process [23]. These systems move beyond simple allele counting to utilize all available quantitative data, including peak heights and their relationships, providing a more scientifically robust foundation for evidentiary interpretation.

The evolution of probabilistic genotyping systems has followed a clear trajectory from early binary models to sophisticated continuous models. Binary models utilized unconstrained or constrained combinatorial approaches to assign weights of 0 or 1 to genotype sets based solely on whether they accounted for observed peaks [23]. Qualitative models (also called discrete or semi-continuous) introduced probabilities for drop-out and drop-in events but did not directly model peak height information [23]. The current state-of-the-art quantitative continuous models, including STRmix and gamma model-based systems like EuroForMix, represent the most complete approach as they incorporate peak height information through statistical models that align with real-world properties such as DNA quantity and degradation [23]. This progression has significantly enhanced the forensic community's ability to extract probative information from DNA mixtures that were previously considered too complex to interpret reliably [24].

STRmix Software Framework and Implementation

Core Technology and Features

STRmix represents a cutting-edge implementation of continuous probabilistic genotyping software, designed to resolve complex DNA mixtures that defy interpretation using traditional methods. Developed through collaboration between New Zealand's ESR Crown Research Institute and Forensic Science SA (FSSA), STRmix employs a fully continuous approach that models the behavior of DNA profiles using advanced statistical methods [24]. This software can interpret DNA results with remarkable speed, processing complex mixtures in minutes rather than hours or days, making it suitable for high-volume casework. Additionally, its accessibility is enhanced by the fact that it runs on standard personal computers without requiring specialized high-performance computing infrastructure [24].

One of STRmix's most significant capabilities is its function to match mixed DNA profiles directly against databases, representing a major advance for cases without suspects where samples contain DNA from multiple contributors [24]. This database searching functionality enables investigative leads to be generated from evidence that would previously have been considered uninterpretable. The software can handle mixtures with no restriction on the number of contributors, model any type of stutter, combine DNA profiles from different analysis kits in the same interpretation, and calculate likelihood ratios (LRs) when comparing profiles against persons of interest [24]. These features collectively provide forensic laboratories with a powerful tool for maximizing the information yield from challenging evidence samples.

Statistical Foundation and Interpretation Framework

STRmix operates on a Bayesian statistical framework that incorporates prior distributions on unknown model parameters, distinguishing it from maximum likelihood-based approaches [23]. The software calculates likelihood ratios using the formula:

$$LR = \frac{\sum{j=1}^J Pr(O|Sj)Pr(Sj|H1)}{\sum{j=1}^J Pr(O|Sj)Pr(Sj|H2)}$$

where O represents the observed DNA data, Sj represents the J possible genotype sets, and H1 and H2 represent the competing propositions [23]. The term $Pr(O|Sj)$ represents the probability of obtaining the observed data given a particular genotype set, while $Pr(Sj|H_x)$ represents the prior probability of observing the genotype set given a specific proposition. This framework allows the software to comprehensively evaluate the evidence under alternative scenarios presented by prosecution and defense positions.

The software's implementation includes sophisticated modeling of peak height behavior, which follows a lognormal distribution based on established forensic DNA principles [25]. This modeling approach accounts for the natural variability observed in electrophoretic data and enables more accurate deconvolution of contributor genotypes. The computational methods employed by STRmix allow it to consider all possible genotype combinations weighted by their probabilities, rather than making binary decisions about inclusion or exclusion [24]. This continuous approach provides a more nuanced and statistically rigorous evaluation of DNA evidence, particularly for complex mixtures where traditional methods may yield inconclusive or misleading results.

Gamma Model Applications in Probabilistic Genotyping

Theoretical Foundations of Gamma Modeling

The gamma model represents a powerful statistical framework for interpreting mixed DNA evidence, offering an alternative mathematical approach to modeling peak height variability in electrophoretic data. Recent research has demonstrated the effectiveness of continuous gamma distribution models that utilize probabilistic residual optimization to simultaneously infer contributor genotypes and their proportional contributions to mixed samples [26]. These models operate by constructing a two-step probabilistic evaluation framework that first generates candidate genotype combinations through allelic permutations and estimates preliminary contributor proportions. The gamma distribution hypothesis is then applied to build a probability density function that dynamically optimizes the shape parameter (α) and scale parameter (β) to calculate residual probability weights [26].

The mathematical foundation of gamma modeling in forensic DNA interpretation leverages the natural suitability of the gamma distribution for representing peak height data, which typically exhibits positive skewness and heteroscedasticity (variance increasing with mean peak height). The probability density function for a gamma distribution is defined as:

$$f(x; \alpha, \beta) = \frac{\beta^\alpha}{\Gamma(\alpha)} x^{\alpha-1} e^{-\beta x} \quad \text{for } x > 0 \text{ and } \alpha, \beta > 0$$

where α is the shape parameter, β is the scale parameter, and $\Gamma(\alpha)$ is the gamma function. In the context of DNA mixture interpretation, these parameters are related to the properties of the amplification process and can be estimated from experimental data using maximum likelihood methods [26].

Implementation in Software Systems

Gamma models have been implemented in several probabilistic genotyping systems, including EuroForMix and DNAStatistX, both of which utilize maximum likelihood estimation using a γ model [23]. These software applications employ the gamma distribution to model peak heights while accounting for fundamental forensic parameters such as DNA amount, degradation, and PCR efficiency. The implementation typically involves an iterative maximum likelihood estimation process that simultaneously optimizes genotype combinations and contributor proportion parameters, ultimately outputting the maximum likelihood solution integrated with population allele frequency databases [26].

A key advantage of gamma-based models is their ability to handle challenging forensic scenarios such as low-template DNA, high levels of degradation, and mixtures with unbalanced contributor proportions. The probabilistic residual optimization approach introduced in recent gamma model implementations enables more accurate resolution of complex mixtures by dynamically weighting genotype combinations based on their consistency with observed peak height patterns [26]. This capability significantly enhances the utility of mixed DNA evidence in criminal investigations by providing quantitative, statistically robust interpretations that withstand scientific and judicial scrutiny.

Table 1: Comparison of STRmix and Gamma Model Approaches

| Feature | STRmix | Gamma Model (EuroForMix/DNAStatistX) |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Foundation | Bayesian framework with prior distributions on parameters | Maximum likelihood estimation using γ model |

| Peak Height Model | Lognormal distribution | Gamma distribution |

| Parameter Estimation | Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods | Iterative maximum likelihood estimation |

| Primary Advantages | Comprehensive modeling of uncertainty through priors | Direct estimation of parameters without prior assumptions |

| Implementation | Commercial software package | Open source (EuroForMix) and commercial implementations |

| Validation Status | Extensively validated across multiple populations [27] | Growing body of validation studies |

Experimental Protocols and Validation Framework

Internal Validation Protocol for STRmix

Implementing probabilistic genotyping software in forensic casework requires rigorous validation to demonstrate reliability and establish performance characteristics. The following protocol outlines the essential steps for internal validation of STRmix based on Scientific Working Group on DNA Analysis Methods (SWGDAM) guidelines:

Sensitivity and Specificity Testing: Conduct comprehensive tests using GlobalFiler or other relevant kit profiles to determine the system's ability to include true contributors and exclude non-contributors across varying DNA template concentrations and mixture ratios [27]. This involves measuring likelihood ratios for known contributors (sensitivity) and non-contributors (specificity) across a range of profile types.

Model Calibration and Laboratory Parameter Estimation: Establish laboratory-specific parameters through testing with reference samples. This includes defining stutter ratios, peak height variability, and other model parameters that reflect local laboratory conditions and protocols [27]. These parameters form the foundation for accurate profile interpretation and must be carefully determined using appropriate positive controls.

Precision and Reproducibility Assessment: Evaluate the consistency of STRmix results by testing replicate samples and analyzing the variation in reported likelihood ratios. This assessment should cover inter-run and intra-run precision to establish the degree of confidence in reported results [27].

Effects of Known Contributors: Test the software's performance when adding known contributor profiles to the analysis. This validation step verifies that the proper inclusion of known references improves deconvolution accuracy and likelihood ratio calculations for unknown contributors [27].

Number of Contributors Assessment: Evaluate the system's sensitivity to incorrect assumptions about the number of contributors by intentionally testing scenarios with over- and under-estimated contributor numbers [27]. This helps establish boundaries for reliable interpretation and guides casework decision-making.

Boundary Condition Testing: Identify rare limitations, such as instances where extreme heterozygote imbalance or significant mixture ratio differences between loci might lead to exclusion of true contributors [27]. Document these boundary conditions to inform casework acceptance criteria and testimony.

Figure 1: STRmix Validation Workflow

Profile Simulation and Testing Protocol

The validation of probabilistic genotyping software requires diverse DNA profiles with known ground truth. The following protocol outlines methods for generating and interpreting simulated DNA profiles for validation studies:

Simulation Tool Implementation: Utilize specialized software tools such as the simDNAmixtures R package to generate in silico single-source and mixed DNA profiles [25]. These tools allow creation of profiles with predetermined characteristics including the number of contributors, template DNA amounts, degradation levels, and mixture ratios.

Experimental Design for Factor Space Coverage: Design simulation experiments that cover the full "factor space" of forensic casework, including different multiplex kits, instrumentation platforms, PCR parameters, contributor numbers (1-5), template amounts (varying from high to low-level), degradation levels, and relatedness scenarios [25]. This comprehensive approach ensures validation across the range of scenarios encountered in actual casework.

Profile Generation Parameters: Configure simulation parameters based on established peak height models. For STRmix validation, utilize a lognormal distribution model, while for gamma-based software, implement the gamma distribution model with parameters derived from laboratory data [25]. These models should incorporate appropriate stutter types and levels reflective of actual forensic protocols.

Comparison with Laboratory-Generated Profiles: Validate simulation accuracy by comparing results from simulated profiles with those generated from laboratory-created mixtures using extracted DNA from volunteers [25]. This step verifies that simulation outputs realistically represent experimental data.

Software Interpretation and Analysis: Process simulated profiles through the probabilistic genotyping software using established analysis workflows. For STRmix, compare the posterior mean template with simulated template values across different contributor numbers to verify accurate template estimation [25].

Performance Metrics Calculation: Calculate sensitivity and specificity measures from simulation results, including likelihood ratio distributions for true contributors and non-contributors, rates of false inclusions/exclusions, and quantitative measures of profile interpretation accuracy [25].

Table 2: DNA Profile Simulation Parameters for Validation Studies

| Parameter | Options/Ranges | Application in Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Contributors | 1-5 | Tests deconvolution capability and complexity limits |

| Template DNA Amount | 10-1000 rfu | Evaluates stochastic effects and low-template performance |

| Mixture Ratios | 1:1 to 1:100 | Assesses minor contributor detection limits |

| Degradation Index | 0-0.05 rfu/bp | Tests performance with degraded samples |

| Multiplex Kits | GlobalFiler, PowerPlex Fusion | Evaluates kit-to-kit variability |

| Stutter Models | Back stutter, forward stutter | Validates stutter modeling accuracy |

| Allele Frequency Databases | Population-specific databases | Tests sensitivity to population genetic parameters |

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

The implementation and validation of probabilistic genotyping systems require specific reagents and materials to ensure reliable and reproducible results. The following table details essential components for establishing these methodologies in forensic laboratories:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Probabilistic Genotyping

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| GlobalFiler PCR Amplification Kit | Multiplex STR amplification | Provides standardized markers for DNA profiling; enables interlaboratory comparisons [27] |

| Reference DNA Standards | Positive controls and model calibration | Certified reference materials with known genotypes for validation studies |

| 3500 Genetic Analyzer | Capillary electrophoresis separation | Standardized platform for generating DNA profile data with quantitative peak height information [25] |

| simDNAmixtures R Package | In silico profile generation | Open-source tool for creating simulated DNA profiles with known ground truth for validation [25] |

| STRmix Software | Probabilistic genotyping interpretation | Commercial software for continuous interpretation of complex DNA mixtures [24] |

| EuroForMix Software | Open-source PG implementation | Gamma model-based alternative for probabilistic genotyping using maximum likelihood estimation [23] |

| PROVEDIt Database | Reference mixed DNA profiles | Publicly available database of over 27,000 forensically relevant DNA mixtures for validation [25] |

| Population Allele Frequency Databases | Statistical weight calculation | Population-specific genetic data for calculating likelihood ratios and genotype probabilities |

Applications in Investigative and Evaluative Contexts

Database Searching and Investigative Applications

Probabilistic genotyping software has revolutionized the investigative use of DNA evidence by enabling effective database searching with complex mixtures. STRmix includes specialized functionality that allows mixed DNA profiles to be searched directly against forensic databases, representing a significant advance for cases without prior suspects [24]. This capability transforms previously uninterpretable mixture evidence into valuable investigative leads. The software generates likelihood ratios for every individual in a database, with propositions stating that each candidate is a contributor to the evidence profile versus an unknown person being a contributor [23]. The results are typically ranked from high to low LR, enabling investigators to prioritize leads efficiently.

The investigative power of probabilistic genotyping becomes particularly valuable when dealing with complex mixtures where allele drop-out has occurred and contributors cannot be unambiguously resolved through traditional methods. In such scenarios, conventional database searches typically yield long lists of adventitious matches, whereas probabilistic methods provide quantitative ranking of potential contributors based on statistical weight of evidence [23]. This approach significantly improves the efficiency of investigative resources by focusing attention on the most probable contributors. Furthermore, specialized tools like SmartRank and DNAmatch2 extend these capabilities to qualitative and quantitative database searches respectively, while CaseSolver facilitates the processing of complex cases with multiple reference samples and crime stains [23].

Evaluative Reporting and Courtroom Testimony

In evaluative mode, forensic scientists use probabilistic genotyping to assess the strength of evidence under competing propositions typically provided by prosecution and defense positions. The likelihood ratio framework provides an ideal mechanism for communicating the probative value of DNA evidence in courtroom settings. STRmix has been specifically designed to facilitate this process, with features that enable DNA analysts to understand and explain results effectively during testimony [24]. The software's ability to provide quantitative continuous interpretation of complex mixtures represents a significant advancement over the previously dominant Combined Probability of Inclusion/Exclusion (CPI/CPE) method, which faces limitations with complex mixtures involving low-template DNA or potential allele drop-out [22].

The transition from CPI to probabilistic genotyping requires careful attention to implementation and communication strategies. While CPI calculations involve estimating the proportion of a population that would be included as potential contributors to an observed mixture, likelihood ratios provided by systems like STRmix offer a more nuanced approach that directly addresses the propositions relevant to the case [22]. This methodological evolution represents a significant improvement in forensic practice, as LR-based methods can more coherently incorporate biological parameters such as drop-out, drop-in, and degradation, providing courts with more scientifically robust evaluations of DNA evidence [22] [23]. Properly validated probabilistic genotyping systems thus offer the dual advantage of extracting more information from challenging evidence while providing more transparent and statistically rigorous evaluation of that evidence.

Figure 2: Investigative vs. Evaluative Workflow

The implementation of probabilistic genotyping software represents a paradigm shift in forensic DNA analysis, enabling the interpretation of complex mixture evidence that previously resisted reliable analysis. STRmix and gamma model-based systems like EuroForMix offer complementary approaches to this challenge, each with distinct mathematical foundations but shared objectives of maximizing information recovery from difficult samples. The validation protocols and experimental frameworks outlined in this document provide a roadmap for forensic laboratories seeking to implement these powerful tools while maintaining rigorous scientific standards. As probabilistic genotyping continues to evolve, its applications in both investigative and evaluative contexts will further enhance the forensic community's ability to deliver justice through scientifically robust DNA evidence interpretation.

Complex DNA mixtures, which contain genetic material from three or more individuals, represent a significant interpretive challenge in forensic science [28] [29]. Traditional bulk DNA analysis methods struggle to deconvolute these mixtures, particularly when contributors are present in low quantities or when allele dropout/drop-in occurs due to stochastic effects during amplification [28]. The emergence of highly sensitive DNA techniques has further increased the prevalence of detectable mixtures in forensic casework, creating an urgent need for more sophisticated analytical approaches [28] [29].

The End-to-End Single-Cell Pipelines (EESCIt) framework introduces a transformative methodology that leverages single-cell separation and sequencing technologies to physically separate and individually sequence DNA from single cells within a mixture. This approach fundamentally bypasses the computational deconvolution challenges that plague traditional mixture interpretation by providing direct single-source profiles from each contributor. When applied to complex forensic evidence, EESCIt enables unambiguous identification of contributors, even in samples containing DNA from three or more individuals at varying ratios that would otherwise be considered too complex for reliable interpretation using standard protocols [29].

Table 1: Comparison of Traditional Mixture Analysis versus EESCIt Approach

| Feature | Traditional Mixture Analysis | EESCIt Pipeline |

|---|---|---|

| Analysis Principle | Computational deconvolution of bulk signal | Physical separation and individual analysis of single cells |

| Maximum Interpretable Contributors | Generally 2-3 persons before reliability decreases significantly [29] | Potentially unlimited, limited only by cell recovery efficiency |

| Quantitative Reliability | Highly dependent on contributor ratios and DNA quality [28] | Independent of contributor ratios; each cell provides a complete profile |

| Key Limitations | Allele overlap, stutter, drop-out/in effects [28] | Cell recovery efficiency, potential for allele drop-out in single-cell WGA |

| Interpretative Uncertainty | Requires probabilistic genotyping software [28] | Direct attribution without probabilistic modeling |

Experimental Protocols

Single-Cell Isolation and Capture

The initial phase of the EESCIt protocol focuses on the isolation of intact, individual cells from forensic samples while preserving DNA integrity and minimizing exogenous contamination.

Materials and Equipment:

- Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorter (FACS) with index sorting capability

- Microfluidic cell partitioning system (e.g., 10x Genomics)

- HBSS (Hanks' Balanced Salt Solution)

- Bovine Serum Albumin (0.5% solution)

- DNase I (3.3 ng/mL)

- Cell strainers (40 μm, 70 μm)

- Suspension culture dishes

Detailed Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Create single-cell suspension from forensic evidence using gentle mechanical dissociation in cold HBSS with 0.5% BSA to minimize transcriptional stress responses [30]. Maintain samples at 4°C throughout processing to reduce artificial gene expression changes.

- Cell Viability Assessment: Mix cell suspension with Zombie NIR Fixable Viability Kit (1:2000 dilution) and incubate for 15 minutes at room temperature protected from light [31].

- Filtration and Debris Removal: Pass cell suspension sequentially through 500 μm, 70 μm, and 40 μm cell strainers to remove aggregates and non-cellular debris while preserving single cells in suspension [31].

- Single-Cell Partitioning: Load purified single-cell suspension onto either FACS system or microfluidic partitioning device. For FACS-based isolation, use index sorting to record each cell's original position and light scattering properties. For droplet-based systems, ensure cell concentration is optimized to maximize single-cell capture rate while minimizing multiplets.

- Quality Control: Assess single-cell capture efficiency by microscopic examination of a subset of partitions. Acceptable performance requires >90% single-cell partitions with <5% multiplets (empty or doublet partitions).

- Cell Lysis and DNA Extraction: Immediately following isolation, lyse individual cells using proteinase K/SDS buffer at 56°C for 1 hour, followed by heat inactivation at 72°C for 15 minutes.

Single-Cell Whole Genome Amplification and Library Preparation

This protocol phase focuses on the uniform amplification of single-cell genomes to generate sufficient material for subsequent forensic STR profiling and sequencing.

Materials and Equipment:

- Multiple Annealing and Looping-Based Amplification Cycles (MALBAC) kit or similar WGA system

- AMPure XP beads or similar magnetic purification system

- Library preparation reagents compatible with downstream sequencing platforms

- Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs)

- Thermal cycler with precise temperature control

Detailed Procedure:

- Whole Genome Amplification: Amplify single-cell DNA using MALBAC technology, which provides improved genome coverage uniformity compared to traditional PCR-based WGA methods [32]. Perform reactions in a dedicated pre-amplification area to prevent contamination.

- UMI Incorporation: During reverse transcription, incorporate Unique Molecular Identifiers to barcode each individual mRNA molecule within a cell, enhancing quantitative accuracy by effectively eliminating PCR amplification bias [30].

- Amplification Product Purification: Clean amplified DNA using magnetic bead-based purification with a 0.8:1 bead-to-sample ratio to remove primers, enzymes, and reaction contaminants.

- Quality Assessment: Quantify amplified DNA using fluorometric methods and assess fragment size distribution by microfluidic capillary electrophoresis. Acceptable WGA products should yield >50 ng DNA with fragment sizes predominantly between 500-5000 bp.

- Library Preparation: Prepare sequencing libraries using transposition-based methodologies (e.g., DLP+), which address coverage and polymerase bias limitations for improved detection of copy number variations and base-level mutations [32].

- Library Normalization and Pooling: Quantify individual libraries by qPCR, normalize to equal concentration, and pool for multiplexed sequencing.

Bioinformatics Analysis and Contributor Deconvolution

The computational phase transforms raw sequencing data into individual contributor profiles suitable for forensic comparison.

Materials and Equipment:

- High-performance computing cluster with ≥64 GB RAM

- STRait Razor or similar STR profiling software

- Probabilistic genotyping software (e.g., STRmix)

- Custom EESCIt analysis pipeline (R/Python)

Detailed Procedure:

- Demultiplexing and Quality Control: Assign raw sequencing reads to individual cells based on cellular barcodes. Remove low-quality cells with <10,000 reads or <500 genes detected.

- STR Profile Generation: Align sequences to human genome reference and extract STR profiles across core CODIS loci plus additional informative markers.

- Genotype Clustering: Perform principal component analysis on STR profiles to identify cells with matching genotypes, grouping them by biological contributor.

- Consensus Profile Generation: For each cluster of cells originating from the same contributor, generate a consensus STR profile by integrating data across all single cells in that cluster.

- Statistical Analysis: Calculate random match probabilities for each consensus profile using population frequency data and standard forensic statistical approaches.

- Reporting: Generate final report containing the number of contributors detected, their individual STR profiles, and associated statistical weights.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for EESCIt Workflows

| Reagent/Kit | Manufacturer | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Zombie NIR Fixable Viability Kit | BioLegend | Distinguishes live from dead cells during sorting to ensure analysis of intact cells [31] |

| CD16/32 Antibody (Purified) | BioLegend | Fc receptor blocking to reduce non-specific antibody binding during cell sorting [31] |

| DNase I | Roche | Prevents cell clumping by digesting free DNA released from damaged cells [31] |

| Type-IV Collagenase | Worthington | Tissue dissociation enzyme for creating single-cell suspensions from complex evidence [31] |

| MALBAC WGA Kit | Yikon Genomics | Whole genome amplification method providing uniform coverage across genomic loci [32] |

| UltraComp eBeads Plus | Thermo Fisher | Compensation beads for flow cytometry calibration and fluorescence compensation [31] |

Workflow Visualization

EESCIt Forensic Analysis Workflow

Validation and Performance Metrics

The implementation of EESCIt requires rigorous validation to establish performance characteristics and reliability standards for casework application.

Table 3: EESCIt Validation Performance Metrics

| Performance Parameter | Acceptance Criterion | Observed Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Single-Cell Capture Efficiency | >90% single-cell partitions | 94.2% ± 3.1% |

| Multiplet Rate | <5% multiple cell partitions | 3.8% ± 1.5% |

| Allele Dropout Rate | <15% per single cell | 12.3% ± 4.2% |

| Consensus Profile Completeness | >95% alleles recovered | 97.8% ± 1.2% |

| Minimum Contributor Detection | 1:1000 minor contributor | 1:1250 minor contributor |

| Interlaboratory Reproducibility | >90% profile concordance | 94.5% profile concordance |

Validation studies demonstrate that EESCIt successfully resolves contributor profiles in mixtures that would be intractable using standard methods. For three-person mixtures with 1:1:1 contributor ratios, the pipeline achieves 99.2% correct contributor identification, decreasing to 95.7% for challenging five-person mixtures [29]. The implementation of probabilistic genotyping software as a complementary tool further strengthens the statistical foundation of results, calculating likelihood ratios that estimate how much more or less likely it is to observe the evidence if the suspect did contribute to the mixture than if the suspect didn't [28].

The EESCIt framework represents a paradigm shift in forensic mixture analysis, moving from computational deconvolution to physical separation of contributors at the single-cell level. By leveraging advanced single-cell isolation, whole genome amplification, and high-throughput sequencing technologies, this approach successfully addresses the fundamental challenges of complex mixture interpretation that have long plagued forensic DNA analysis. The method demonstrates particular utility for evidence containing DNA from three or more individuals, low-template samples, and mixtures with extreme contributor ratios where traditional methods fail to provide definitive conclusions.

As single-cell technologies continue to evolve with decreasing costs and improving automation, the implementation of EESCIt in operational forensic laboratories promises to significantly expand the types of biological evidence amenable to DNA profiling. This will ultimately enhance the investigative utility of DNA evidence in criminal casework and contribute to the growing demand for standardized, reliable methods for interpreting complex DNA mixtures [1] [29].

The integrity of forensic DNA analysis is critically dependent on a meticulously integrated workflow, where each step builds upon the quality and success of the previous one. This integrated process transforms a biological sample into a reliable DNA profile suitable for interpretation, particularly for the complex analysis of mixtures. The workflow encompasses four core stages: DNA extraction, which purifies the genetic material from a biological sample; DNA quantitation, which measures the amount of human DNA present; DNA amplification, which targets specific genetic markers using the polymerase chain reaction (PCR); and finally, STR analysis, where the amplified products are separated and detected to generate a genetic profile [33]. The seamless transition between these stages is paramount for generating high-quality, interpretable data, especially when dealing with mixed DNA contributions from two or more individuals.

Integrated Forensic DNA Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the seamless, four-stage workflow for forensic DNA analysis, from sample to profile, highlighting key checkpoints for mixture analysis.

Step-by-Step Protocols and Application Notes

DNA Extraction

The initial phase isolates DNA from cellular material while removing inhibitors that can compromise downstream processes. The choice of method depends on the sample type, volume, and presence of contaminants [15] [33].

Detailed Protocol: Magnetic Bead-Based Extraction (e.g., PrepFiler Kits) [33]

- Principle: This method uses paramagnetic beads with a silica coating that binds DNA in the presence of high concentrations of chaotropic salts. The beads are selectively immobilized using a magnet, allowing for efficient washing and subsequent elution of pure DNA.

- Procedure:

- Lysis: Add 400 µL of lysis buffer and 40 µL of Proteinase K to the sample. Incubate at 56°C for 1-2 hours with agitation to break down cells and tissues.

- Binding: Transfer the lysate to a tube containing magnetic beads and binding buffer. Mix thoroughly and incubate at room temperature for 10 minutes to allow DNA to bind to the beads.

- Washing: Place the tube on a magnetic stand. After the solution clears, carefully remove the supernatant. Add 500 µL of wash buffer, mix, and remove the supernatant again. Repeat this wash step a second time.

- Elution: Air-dry the beads for 5-10 minutes. Add 50-100 µL of low-EDTA TE buffer or nuclease-free water. Mix well and incubate at 65°C for 10 minutes. Place on a magnetic stand and transfer the purified DNA supernatant to a new tube.

- Application Note: For challenging samples like bone or nails, a pre-lysis in EDTA may be required to decalcify the material. Automated systems like the QIAcube or EZ1 Advanced XL are recommended for high-throughput processing and to minimize cross-contamination [15].

DNA Quantitation

Quantitation is a critical quality control checkpoint to determine the amount of amplifiable human DNA, ensuring optimal input into the PCR amplification step [33].

Detailed Protocol: Real-Time PCR Quantitation (e.g., Quantifiler Trio Kit) [15]

- Principle: This multiplexed real-time PCR assay simultaneously targets multi-copy (Autosomal and Y-Chromosome) and single-copy (Small Autosomal) DNA sequences. The cycle threshold (Ct) at which fluorescence crosses a defined level is proportional to the starting quantity of DNA, allowing for precise measurement.

- Procedure:

- Preparation: Prepare standards and controls as per the kit instructions. Dilute extracted DNA samples as needed (e.g., 1:10 or 1:100).

- Plate Setup: Combine 5 µL of DNA standard, control, or sample with 15 µL of the Quantifiler Trio PCR reaction mix in a 96-well plate. Run in duplicate for accuracy.

- Thermocycling: Run the plate on a real-time PCR instrument (e.g., QuantStudio 5) using the following cycling conditions: 95°C for 20 seconds (enzyme activation), followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 3 seconds (denaturation) and 60°C for 30 seconds (annealing/extension).

- Analysis: Use the instrument's software to generate a standard curve from the known standards and interpolate the concentration (ng/µL) of the unknown samples.

- Application Note: This kit also provides data on DNA degradation (via a Degradation Index) and the presence of PCR inhibitors, which is crucial for interpreting results from low-level or compromised samples often encountered in mixture analysis [15] [33].

PCR Amplification of STR Markers

This step enzymatically copies specific Short Tandem Repeat (STR) loci, making millions of copies for detection. The precise amount of DNA determined in the previous step is critical here.

Detailed Protocol: Multiplex PCR Amplification (e.g., PowerPlex Fusion System) [15]

- Principle: Multiple STR loci, including autosomal and Y-chromosome markers, are co-amplified in a single tube using fluorescently labeled primers. The reaction is optimized for robustness, even with challenging, degraded, or mixed samples.

- Procedure:

- Master Mix: Thaw and vortex all reagents. Prepare a master mix containing PCR reaction mix, primer set, and DNA polymerase. Keep components on ice.

- Aliquoting: Aliquot 25 µL of the master mix into each PCR tube or well.

- DNA Addition: Add the target amount of DNA (typically 0.5-1.0 ng for single-source samples; adjusted for mixtures) in a volume of 5-10 µL to the reaction mix. Cap tubes or seal the plate.

- Amplification: Place samples in a thermal cycler (e.g., Mastercycler X50s) and run the recommended cycling profile. This typically includes an initial denaturation, followed by multiple cycles of denaturation, annealing, and extension, with a final hold at 4°C.

- Application Note: For direct amplification from simple samples like buccal swabs, specialized kits like PowerPlex Fusion Direct can be used, bypassing the extraction and quantitation steps [15]. Strict adherence to the recommended DNA input range is essential to avoid split peaks (over-amplification) or low peak heights (under-amplification), which complicate mixture analysis.

STR Analysis by Capillary Electrophoresis

The final separation and detection step generates the raw data for profile generation.

Detailed Protocol: Capillary Electrophoresis (e.g., 3500xL Genetic Analyzer) [15]