Advances in Microanalysis of Gunshot Residue and Explosives: From Foundational Research to Forensic Application

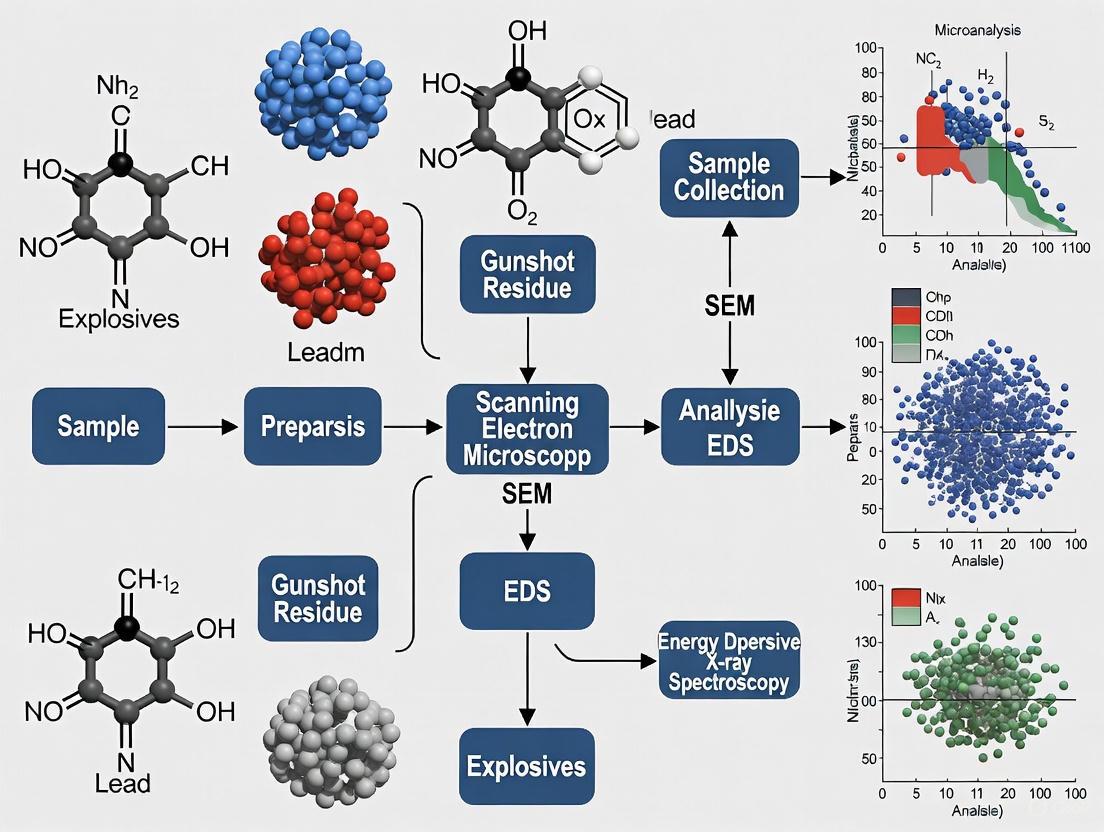

This article provides a comprehensive review of the fundamental research and technological advancements in the microanalysis of gunshot residue (GSR) and explosives, critical for forensic science and investigative applications.

Advances in Microanalysis of Gunshot Residue and Explosives: From Foundational Research to Forensic Application

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive review of the fundamental research and technological advancements in the microanalysis of gunshot residue (GSR) and explosives, critical for forensic science and investigative applications. It explores the foundational chemistry and composition of inorganic and organic residues, detailing the evolution and current state of analytical methodologies, including scanning electron microscopy with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDS), spectroscopy, and chromatography. The scope extends to troubleshooting persistent challenges such as environmental contamination, lead-free ammunition, and GSR persistence, while evaluating the validation and comparative efficacy of emerging techniques like laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy (LIBS), electrochemical sensors, and Raman spectroscopy. This synthesis is tailored for researchers, forensic scientists, and development professionals seeking to enhance analytical precision and develop novel applications in forensic microanalysis.

The Core Composition and Forensic Significance of Gunshot Residue

The discharge of a firearm is a rapid, complex chemical event that produces a characteristic residue, a complex mixture of organic and inorganic materials. Gunshot residue (GSR) serves as crucial trace evidence in firearm-related investigations, aiding in the reconstruction of events and establishing shooter involvement [1]. The definitive analysis of GSR requires a fundamental understanding of its two principal component classes: inorganic gunshot residue (IGSR), which originates predominantly from the primer, and organic gunshot residue (OGSR), which derives mainly from the propellant (gunpowder) and associated additives [2] [3]. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of the chemistry, analysis, and interpretation of these components within the context of fundamental research microanalysis for explosives and GSR.

Core Chemical Components of GSR

Inorganic GSR (IGSR) from the Primer

The primer is a shock-sensitive mixture contained within the cartridge casing that, upon impact from the firearm's firing pin, undergoes deflagration to ignite the main propellant charge. The inorganic components of GSR predominantly stem from this primer mixture [3].

- Characteristic Elements: Traditional primer formulations are characterized by the presence of lead (Pb), barium (Ba), and antimony (Sb). These elements originate from lead styphnate (the primary explosive), barium nitrate (the oxidizer), and antimony sulfide (the fuel) [2] [4] [3].

- Particle Morphology: The violent, high-temperature reaction causes these elements to vaporize and subsequently re-condense into distinctive, often spherical, particulates. The combination of their elemental profile and spherical morphology is a key identifier for IGSR [2].

- Evolution of Formulations: Due to environmental and health concerns, "heavy-metal-free" or "green" ammunition is increasingly common. These formulations replace Pb, Ba, and Sb with other compounds, such as copper, zinc, titanium, strontium, or organic primers based on materials like tetracene or diazodinitrophenol. This shift presents new challenges for forensic analysis, as the resulting IGSR particles are less characteristic and more common in the environment [3].

Table 1: Characteristic Inorganic GSR Components from the Primer

| Source | Component | Chemical Formula | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primer | Lead Styphnate | C₆HN₃O₈Pb | Primary explosive, initiator [5] |

| Primer | Barium Nitrate | Ba(NO₃)₂ | Oxidizer [2] [5] |

| Primer | Antimony Sulfide | Sb₂S₃ | Fuel [2] [5] |

| Primer | Zinc, Titanium, Strontium | Zn, Ti, Sr | Metals found in some "green" primers [3] |

Organic GSR (OGSR) from the Propellant

The propellant, or gunpowder, is the main energy source that propels the bullet through the barrel. Its incomplete combustion leads to the deposition of organic gunshot residue [2] [3].

- Propellant Types: Smokeless gunpowder, the most common propellant, can be single-based (nitrocellulose, NC), double-based (NC and nitroglycerin, NG), or triple-based (NC, NG, and nitroguanidine) [3].

- Key Additives and Their Markers: Propellant formulations include various additives to control stability, burn rate, and wear. The combustion and degradation of these compounds produce the organic markers targeted in OGSR analysis.

- Stabilizers: Diphenylamine (DPA) is added to prevent the decomposition of nitrocellulose and nitroglycerin. Its nitrated derivatives, such as 2-nitrodiphenylamine (2-NDPA) and 4-nitrodiphenylamine (4-NDPA), are also important OGSR analytes [2] [5].

- Plasticizers and Coolants: Ethyl centralite (EC) and methyl centralite (MC) act as stabilizers and plasticizers [2]. Dimethyl phthalate (DMP) is another common plasticizer [2].

- Explosives: Nitroglycerin (NG) is a key component in double-based propellants [3] [5].

- Deposition and Persistence: OGSR is dispersed as both unburned/partially burned propellant particles and as vapors that condense on surfaces. These condensed compounds adhere to skin via lipophilic interactions and are not prone to secondary transfer, a significant advantage over IGSR. The primary mechanisms of loss are evaporation and skin permeation over several hours [2].

Table 2: Characteristic Organic GSR Components from the Propellant

| Component | Functional Role | Significance in OGSR Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Nitrocellulose (NC) | Primary explosive propellant [3] | Base component of smokeless powder. |

| Nitroglycerin (NG) | Explosive propellant, plasticizer [3] [5] | Key marker for double-based powders. |

| Diphenylamine (DPA) | Stabilizer [2] [5] | A primary target; its degradation products (e.g., nitrated DPAs) are also analyzed. |

| Ethyl Centralite (EC) | Stabilizer, plasticizer [2] [5] | A compound with high evidentiary value when detected in combination with NG [6] [7]. |

| 2,4-Dinitrotoluene (2,4-DNT) | Additive [5] | A common OGSR analyte. |

| Dimethyl Phthalate (DMP) | Plasticizer [2] | A target compound in OGSR studies. |

Advanced Analytical Methodologies

Analytical Techniques for IGSR and OGSR

A range of analytical techniques is employed for GSR detection, each with specific strengths and applications.

Table 3: Analytical Techniques for Gunshot Residue Analysis

| Technique | Target | Principle | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SEM-EDX [2] [3] | IGSR | Combines electron microscopy for particle morphology with X-ray spectroscopy for elemental composition. | Non-destructive; gold standard for IGSR; provides simultaneous morphological and elemental data. | Time-consuming (2-8 hrs/sample); requires high vacuum; incompatible with volatile OGSR. |

| ICP-MS [6] [3] | IGSR | Ionizes sample and separates ions by mass-to-charge ratio for elemental (and isotopic) quantification. | Extremely sensitive (ppb-ppt); can analyze "green" primers; provides isotopic information. | Destructive; requires sample digestion; loses particle morphology. |

| LC-MS/MS [5] | OGSR & IGSR | Chromatographic separation followed by tandem mass spectrometry detection. | Can target both OGSR and IGSR (via complexation) in a single run (~20 min); high sensitivity and selectivity for organics. | Destructive; requires extraction. |

| Raman Spectroscopy [1] | OGSR & IGSR | Measures inelastic scattering of light to provide a molecular "fingerprint". | Can provide information on both organic and inorganic compounds; minimal sample preparation. | Can be affected by fluorescence; lower sensitivity compared to MS. |

| IMS [2] | OGSR | Separates gas-phase ions in an electric field based on size and shape. | Potential for rapid field screening. | Requires significant development for reliable field use; pattern matching algorithms need refinement. |

Detailed Experimental Workflow for Combined OGSR/IGSR Analysis

The following workflow details a methodology for the simultaneous extraction and analysis of organic and inorganic GSR components from a single sample using Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), as demonstrated in recent research [5].

Sample Collection

- Procedure: Hand swabs are collected from a suspect using a moistened swabbing material. The study identified muslin and a Nomex blend as optimal media due to their efficiency in collecting both particulate and vapor-deposited residues [2].

- Rationale: The goal is to maximize collection efficiency from the skin surface. The sampling medium must be wettable with a benign solvent (e.g., isopropanol or ethanol), compatible with multiple instruments, and free of contaminants [2].

Swab Extraction and Complexation

This is the critical sample preparation step that enables simultaneous analysis.

- Extraction: The swab is extracted using a suitable solvent, typically methanol or acetonitrile, to dissolve the OGSR compounds and any metallic particulates [5].

- Complexation Chemistry: To enable the chromatographic separation and MS detection of inorganic ions, the extract is treated with complexing agents.

- Macrocycle Complexation: 18-crown-6-ether (18C6) is added to form host-guest complexes with lead (Pb²⁺) and barium (Ba²⁺) ions. This encapsulation allows the metals to elute from the chromatographic column [5].

- Chelation: Tartaric acid is used as a chelating agent to complex with antimony (Sb) ions, similarly enabling its analysis via LC-MS [5].

- Benefit: This complexation strategy retains the natural isotopic abundance patterns of the elements, allowing for unambiguous identification [5].

Instrumental Analysis via LC-MS/MS

- Chromatographic Separation: The extracted and complexed sample is injected into the LC system. The column separates the OGSR compounds (e.g., DPA, NG, EC) and the metal-complexes based on their chemical properties [5].

- Tandem Mass Spectrometry Detection: The eluting compounds are ionized and analyzed by the mass spectrometer. The MS/MS configuration provides high selectivity and sensitivity by isolating precursor ions and analyzing their characteristic fragment ions.

- OGSR: Identified based on retention time and unique fragmentation patterns.

- IGSR: The metal complexes are detected, and the isotopic ratios of the complexed metals (e.g., Pb²⁺-18C6) are used for confirmation [5].

- Performance: This method has a total analysis time of under 20 minutes per sample, with linear dynamic ranges in the low parts-per-billion (ppb) for OGSR and low parts-per-million (ppm) for IGSR [5].

Key Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details essential reagents and materials used in the featured LC-MS/MS protocol and other standard GSR analyses [2] [5].

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for GSR Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Brief Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Muslin / Nomex Swabs | Sample Collection | Optimal sampling media for efficient collection of both particulate and condensed OGSR from skin [2]. |

| 18-Crown-6-Ether (18C6) | Complexation Agent | Forms host-guest complexes with Pb²⁺ and Ba²⁺ ions, allowing their analysis by LC-MS [5]. |

| Tartaric Acid | Complexation Agent | Acts as a chelating agent to complex with antimony (Sb) ions for LC-MS analysis [5]. |

| Methanol (MeOH) / Acetonitrile (ACN) | Extraction Solvent | Organic solvents used to efficiently extract OGSR compounds and solubilize metallic residues from collection swabs [5]. |

| Diphenylamine (DPA) & Nitrated DPA Standards | Analytical Standards | High-purity reference standards used for calibration, identification, and quantification of OGSR components [2] [5]. |

| Lead, Barium, Antimony Standard Solutions | Analytical Standards | Certified reference materials for calibrating IGSR detection, whether by SEM-EDX, ICP-MS, or complexation LC-MS [5]. |

Critical Considerations for Research and Interpretation

Stability and Storage of GSR Evidence

The integrity of GSR evidence is highly dependent on storage conditions.

- OGSR Stability: Organic compounds are volatile and subject to degradation. Hand swab samples require cold, dark storage conditions and should be analyzed within 2 weeks of collection when stored at -20°C. Significant degradation of volatile compounds like DMP occurs after a few days at room temperature [2].

- IGSR Stability: Inorganic particles are generally more robust. Recent studies indicate that IGSR particles remain chemically stable for at least 60 days under various storage conditions, including uncontrolled ambient conditions, with no significant variation in their elemental profiles [1].

Evidentiary Value and Population Prevalence

Interpreting GSR results requires understanding the potential for environmental contamination.

- OGSR Specificity: While some OGSR components like 2,6-dinitrotoluene (2,6-DNT) can be found in non-shooting environments, others like nitroglycerin (NG), especially when detected in conjunction with markers like ethyl centralite (EC), hold stronger evidentiary value [6] [7]. The analysis of multiple OGSR compounds in combination is crucial.

- IGSR and "Green" Ammunition: The probative value of traditional IGSR (Pb-Sb-Ba) is high, but the rise of "green" ammunition using common metals (e.g., zinc, titanium) or organic primers diminishes the evidential weight of IGSR alone, necessitating combined OGSR/IGSR analysis [3].

- Secondary Transfer: A key difference between components is that vapor-deposited OGSR is not prone to secondary transfer, whereas IGSR particulates can be transferred via contact with contaminated surfaces [2]. This makes the detection of specific, non-transferable OGSR compounds highly significant for linking a suspect directly to a firing event.

The definitive analysis of gunshot residue rests on a comprehensive understanding of its dual nature. Inorganic residues from the primer and organic residues from the propellant provide complementary lines of evidence. While established methods like SEM-EDX remain the standard for IGSR, the evolution of ammunition and the need for higher specificity are driving the adoption of sophisticated, combined analytical approaches. Techniques like LC-MS/MS with complexation chemistry represent the cutting edge, allowing for the simultaneous detection of organic and inorganic constituents from a single sample, thereby significantly increasing the confidence of results. Future research in fundamental microanalysis will continue to refine these protocols, expand population studies for background prevalence, and develop standardized interpretation frameworks to fully leverage the evidentiary power of GSR in forensic investigations.

The forensic analysis of gunshot residue (GSR) is a critical discipline for reconstructing shooting incidents and establishing connections between individuals, firearms, and discharge events. The evolution of GSR analysis reflects a broader trajectory in forensic science, moving from presumptive chemical tests toward sophisticated instrumental microanalysis. This progression has been driven by the need for higher specificity, sensitivity, and quantitative results, particularly within fundamental research on explosives and micro-traces. Early methods provided a foundation for scene assessment but were plagued by limitations, while contemporary techniques like scanning electron microscopy with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDS) and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) now offer definitive characterization of both inorganic and organic components of GSR. This whitepaper details the historical development, current methodologies, and emerging trends in GSR analysis, providing researchers and forensic professionals with a comprehensive technical guide grounded in the latest advancements.

The Early Era: Colorimetric and Presumptive Tests

The initial phase of GSR analysis was dominated by colorimetric tests, which relied on chemical reactions to produce a visible color change indicating the possible presence of residue constituents.

Key Historical Tests and Protocols

- Paraffin Test (Dermal Nitrate Test): This early test involved coating a suspect's hands with molten paraffin wax. Once solidified and peeled off, the wax cast was treated with a solution of diphenylamine in sulfuric acid. The development of blue spots was interpreted as a positive reaction for nitrates and nitrites from gunpowder [8] [9]. Its protocol is now obsolete due to a high frequency of false positives from common environmental contaminants like fertilizers and urine [8] [9].

- Walker Test: This was a transfer technique used to detect nitrite residues on clothing. A document moistened with a reagent containing 2-naphthylamine and sulfanilic acid in acid was pressed against the questioned fabric. The appearance of an orange-red color indicated the presence of nitrites [9].

- Modified Griess Test: This test improves upon earlier methods for detecting nitrite compounds, a combustion by-product of smokeless powder. The protocol involves transferring nitrites from a fabric sample to a reagent-soaked paper using a heated press. The reagent, typically containing sulfanilamide and N-(1-naphthyl)ethylenediamine in an acidic medium, produces an orange-red color with nitrites [8] [9]. It remains a valuable tool for determining a gun's muzzle-to-target distance.

- Sodium Rhodizonate Test: This test is used to detect the presence of lead and, to a lesser extent, barium. The protocol involves treating the sample with a sodium rhodizonate solution; lead produces a pink-red or purple color, while barium produces a reddish-brown color. It is often used to confirm bullet holes [9].

- Harrison and Gilroy Test: Introduced in 1959, this test sequentially applied different reagents to a single sample swab to detect antimony (orange color), barium (red-brown spots), and lead (blue-black spots). However, its poor sensitivity and specificity make it unreliable for modern casework [9].

Table 1: Summary of Historical Colorimetric Tests for GSR

| Test Name | Target Analyte | Key Reagents | Positive Result Indicator | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paraffin Test | Nitrates/Nitrites | Diphenylamine, Sulfuric Acid | Dark Blue Spots | High false positives from fertilizers, urine [8] [9] |

| Walker Test | Nitrites | Naphthylamine, Sulfanilic Acid | Red Coloration | Lacks specificity for GSR [9] |

| Modified Griess Test | Nitrites | Sulfanilamide, N-(1-naphthyl)ethylenediamine | Orange-Red Coloration | Detects nitrites, not specific to GSR [9] |

| Sodium Rhodizonate | Lead, Barium | Sodium Rhodizonate | Red or Purple Color (Pb) | Environmental sources of heavy metals [9] |

| Harrison & Gilroy | Antimony, Barium, Lead | Various Sequential Reagents | Orange, Red-Brown, Blue-Black Colors | Low sensitivity and specificity [9] |

Limitations and Historical Significance

These colorimetric tests were groundbreaking for their time, offering a practical, if rudimentary, means of initial scene assessment. However, they are destructive, lack specificity for GSR due to ubiquitous environmental interferents, and provide no information on the elemental or molecular composition of the residue [8] [10]. Their decline marked a necessary shift toward instrumental methods capable of providing confirmatory evidence.

The Instrumental Revolution: Microanalysis of Inorganic GSR

The introduction of instrumental techniques marked a paradigm shift, enabling the definitive identification of GSR through its unique inorganic elemental signature.

Scanning Electron Microscopy with Energy-Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy (SEM-EDS)

SEM-EDS emerged as the gold standard for inorganic GSR (IGSR) analysis and remains the cornerstone of modern GSR analysis in forensic laboratories worldwide [11]. This technique provides simultaneous morphological and elemental information from individual particles.

Experimental Protocol: The standard methodology, as outlined in ASTM E1588-20, involves collecting samples from a person of interest (typically hands, face, or clothing) using adhesive aluminum stubs [12] [11]. The stub is then placed in the SEM vacuum chamber. The electron beam scans the sample surface, and detectors collect multiple signals:

- Secondary Electrons (SE): Generate high-resolution topographic images, revealing the characteristic spherical morphology of GSR particles formed from condensation [11].

- Backscattered Electrons (BSE): Produce compositional contrast, where heavier elements (like Pb, Ba, Sb) appear brighter, guiding the analyst to potential GSR particles [11].

- Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS): When the electron beam excites an atom, it emits characteristic X-rays. The EDS detector collects this signal to determine the elemental composition of each particle [11].

Interpretation and Classification: Particles are classified based on their elemental composition into categories defined by ASTM E1588-20 [12]:

- Characteristic of GSR: Contain all three core elements (Pb, Ba, Sb).

- Consistent with GSR: Contain two of the three elements (e.g., Pb-Ba, Sb-Ba).

- Commonly Associated with GSR: Contain a single element like Ba, Pb, or Sb.

Table 2: ASTM E1588-20 Classification of Inorganic GSR Particles [12]

| Particle Category | Elemental Composition | Interpretation and Discriminating Power |

|---|---|---|

| Characteristic of GSR | Lead (Pb), Barium (Ba), Antimony (Sb) | Considered unique to primer discharge; highest evidential value. |

| Consistent with GSR | Combinations of two elements (e.g., Pb-Ba, Sb-Ba) | Strongly associated with GSR, but requires more contextual information. |

| Commonly Associated with GSR | Single elements (Ba, Pb, or Sb) | Least discriminating, as these elements are common in the environment. |

Advancements and Complementary Techniques

While SEM-EDS is powerful, research continues into complementary methods. Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS) has shown significant potential for rapid elemental analysis of GSR, including from lead-free ammunition, with the advantage of minimal sample destruction [8]. Furthermore, the rise of "non-toxic" or heavy-metal-free ammunition, which uses compositions like titanium, zinc, and aluminum, has challenged traditional SEM-EDS classification and spurred the development of new databases and analytical criteria [8] [12].

The Modern Paradigm: Integration of Organic GSR and Multi-Method Approaches

Recognizing the limitations of analyzing inorganic components alone, the field has expanded to integrate the analysis of organic GSR (OGSR), leading to a more robust and comprehensive evidential framework.

Analysis of Organic GSR (OGSR)

OGSR originates from the propellant (smokeless powder) and its additives. Key analytes include nitrocellulose (NC), nitroglycerin (NG), stabilizers like diphenylamine (DPA), ethyl centralite (EC), and flash inhibitors like dinitrotoluene (DNT) [8] [12].

- Primary Analytical Protocols:

- Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) & Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS): These are the principal confirmatory techniques for OGSR. Samples are typically collected via swabbing or solvent washing. After extraction, the analytes are separated by chromatography and identified by their mass spectra. LC-MS/MS is particularly favored for its high sensitivity and ability to detect a broad range of propellant-related compounds without derivatization [12] [13].

- Ion Mobility Spectrometry (IMS): Often deployed as a rapid screening tool at airports and security checkpoints, IMS can detect trace explosives and propellant vapors but is generally considered less specific than chromatographic methods [8].

A Multi-Method and Data-Integration Framework

The most advanced current research employs a multi-method approach, combining inorganic and organic analysis to drastically improve the confidence of GSR identification [13].

A landmark 2025 study by Ledergerber et al. exemplifies this paradigm. The experimental protocol integrated:

- Real-Time Atmospheric Sampling: Using particle counters and custom air samplers to measure the concentration and size distribution of airborne GSR before, during, and after a discharge event [13].

- High-Speed Videography and Laser Sheet Scattering: To visually capture and qualitatively analyze the flow dynamics and dispersion of the GSR plume under different environmental conditions [13].

- Confirmatory Chemical Analysis: Subsequent analysis of collected samples using SEM-EDS for IGSR and LC-MS/MS for OGSR to confirm the elemental and molecular makeup of the residues [13].

This holistic methodology provided breakthrough insights into how long GSR remains airborne and how it deposits on shooters, bystanders, and passers-by, directly addressing complex interpretation challenges in casework [13].

Statistical Interpretation and Machine Learning

The complexity of integrated IGSR and OGSR data has necessitated advanced statistical interpretation. Likelihood Ratio (LR) frameworks are increasingly being adopted to quantitatively assess the strength of evidence, comparing the probability of finding the GSR traces under competing prosecution and defense hypotheses [12]. Furthermore, machine learning (ML) and neural networks (NN) are being trained on large datasets to classify samples as originating from a shooter or a non-shooter with high accuracy, moving analysis beyond categorical reporting toward probabilistic assessment [12].

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Modern GSR Analysis Techniques

| Analytical Technique | Target GSR Component | Key Advantages | Key Limitations / Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| SEM-EDS | Inorganic (IGSR) | Gold standard; combined morphology & elemental data; automated particle analysis. | Time-consuming; high equipment cost; challenged by "lead-free" ammunition [8] [12]. |

| LIBS | Inorganic (IGSR) | Very rapid analysis; portable systems available; minimal sample destruction. | Less established for casework; database development ongoing [8]. |

| LC-MS/MS | Organic (OGSR) | High sensitivity & specificity; confirmatory for propellant compounds. | Lower persistence of OGSR on skin (~1 hour); complex sample preparation [9] [12]. |

| IMS | Organic (OGSR) | Real-time, high-throughput screening; portable. | Less specific; prone to false positives from environmental compounds [8]. |

| Multi-Method (e.g., SEM-EDS + LC-MS/MS) | Inorganic & Organic | Maximizes specificity and evidential weight; enables complex transfer studies. | Data integration complexity; requires significant resources and expertise [13]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Reagents and Materials for GSR Research and Analysis

| Item Name | Function / Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Adhesive Aluminum Stubs | Sample collection for SEM-EDS analysis. Standardized substrate that is conductive and compatible with SEM vacuum chambers [13] [11]. | |

| Modified Griess Test Reagents | Presumptive test for nitrite compounds on surfaces. Used for muzzle-to-target distance estimation. Typically includes sulfanilamide and N-(1-naphthyl)ethylenediamine in acid [9]. | |

| Sodium Rhodizonate Solution | Presumptive test for lead and barium. Used to confirm bullet holes and GSR patterns on surfaces [9]. | |

| Organic Solvents (e.g., Acetonitrile) | Extraction of organic GSR compounds from swabs or collection media prior to LC-MS/MS or GC-MS analysis [12]. | |

| SEM Conductive Coating (e.g., Carbon) | Applied to non-conductive samples to prevent charging under the electron beam, ensuring high-quality imaging [11]. | |

| Certified Reference Materials | Calibration and validation of instrumental methods (SEM-EDS, LC-MS/MS). Includes elemental standards and certified propellant mixtures. |

The evolution of GSR analysis from basic color tests to integrated instrumental microanalysis illustrates a relentless pursuit of scientific rigor in forensic science. The initial presumptive tests, while historically significant, have been superseded by powerful techniques like SEM-EDS and LC-MS/MS that provide definitive, court-defensible evidence. The current state-of-the-art involves multi-modal approaches that combine inorganic and organic analysis with advanced data interpretation using likelihood ratios and machine learning. Future directions will focus on standardizing these integrated methods, expanding databases for new ammunition types, and developing robust, portable technologies for on-site analysis. This ongoing refinement ensures that GSR analysis remains a vital and reliable tool for fundamental explosives research and the administration of justice.

The Impact of Lead-Free Ammunition on GSR Elemental Profiles and Detection

The proliferation of lead-free ammunition represents a significant paradigm shift in forensic science, particularly in the domain of gunshot residue (GSR) analysis. Driven by health and environmental concerns over lead exposure, these new ammunition formulations fundamentally alter the elemental composition of residual particles produced during firearm discharge [14] [8]. This transformation challenges the established analytical frameworks that have long relied on detecting lead (Pb), barium (Ba), and antimony (Sb) as characteristic signatures of firearm discharge [15] [16]. The forensic community now faces the critical task of developing new identification criteria and analytical methodologies to maintain evidentiary standards in cases involving lead-free ammunition. This technical guide examines the altered elemental profiles of GSR from lead-free primers, evaluates advanced detection techniques, and provides detailed experimental protocols to support fundamental research in microanalysis of gunshot residue and explosives.

Elemental Profile Shifts in Lead-Free Ammunition

The elimination of lead and other heavy metals from ammunition primers has necessitated the use of alternative chemical compositions, resulting in GSR particles with distinctly different elemental signatures compared to conventional ammunition.

Table 1: Characteristic Elemental Compositions of Conventional vs. Lead-Free GSR Particles

| Ammunition Type | Characteristic Elements | Common Elemental Combinations | Source Components |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional | Pb, Sb, Ba | Pb-Sb-Ba, Pb-Sb, Pb-Ba, Sb-Ba | Primer: lead styphnate (initiator), barium nitrate (oxidizer), antimony sulfide (fuel) [17] [18] |

| Lead-Free | Zn, Ti, Cu, Al, K, Si, Gd, Sn | Ti-Zn, Al-Zn, Cu-Zn, K-Cl-Zn, Si-K-Al, Gd-Ti-Zn [19] [8] | Varied by manufacturer; may include zinc peroxide, titanium powder, tetrazene, diazonitrophenol, nitrocellulose [18] |

The fundamental challenge in GSR analysis of lead-free ammunition stems from the absence of standardized formulations across manufacturers. Unlike conventional primers that largely adhered to the Pb-Sb-Ba triad, lead-free primers employ diverse chemistries [19] [16]. Research has identified particles containing gadolinium (Gd), titanium (Ti), zinc (Zn), or gallium (Ga) combined with copper (Cu) and tin (Sn) as characteristic of certain lead-free formulations [19]. Other studies have reported GSR particles with combinations such as Ti-Zn-K-Cu-Zn and Al-Si-K-S-Cu-Zn [19]. Some manufacturers have introduced distinctive markers like samarium oxide and titanium oxide, resulting in Sm-K-Si-Ti-Ca-Al-type particles that facilitate identification [19].

Table 2: Quantitative Elemental Analysis of Lead-Free GSR Using Various Techniques

| Analytical Technique | Detected Elements in Lead-Free GSR | Particle Size Range | Analysis Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| SEM-EDX | Al, Si, K, Ti, Fe, S, Cu, Zn [19] [8] | 0.5-5 μm [18] | Hours (including manual verification) |

| LIBS | Cu, Al, Zn, K, Ti [19] | >1 μm [19] | Minutes (rapid screening) |

| sp-ICP-TOF-MS | Multi-element fingerprints, including trace metals [20] | Nanoparticles (smaller than SEM-EDX detection) [20] | Minutes (thousands of particles per minute) |

| LC-QTOF MS | Organic components: NQ, HMX, RDX, DNAN, TNT, PENT, MC, EC, DPA, DMP, DEP [21] | Not particle-based | 30-minute analysis [21] |

The morphological characteristics of GSR particles remain important for distinguishing them from environmental contaminants. Lead-free GSR particles typically maintain the spherical, molten metal appearance characteristic of fast-cooled droplets, allowing for differentiation from crystalline environmental particles even when elemental composition overlaps with common contaminants like paints containing titanium and zinc [18].

Analytical Challenges and Methodological Adaptations

Limitations of Standard SEM-EDX Protocols

The traditional SEM-EDX approach, standardized in ASTM E1588, faces significant challenges with lead-free ammunition. This method relies on automated particle screening based on the Pb-Sb-Ba elemental combination, which is inherently ineffective for detecting the varied elemental profiles of lead-free GSR [15] [22]. The result is a potentially higher rate of false negatives when examiners rely exclusively on established protocols [16]. Additionally, particles from lead-free ammunition may be smaller than those from conventional ammunition, potentially falling below the optimal detection range of standard SEM-EDX systems [20].

Environmental contamination presents another significant challenge. Many elements found in lead-free GSR, such as zinc, titanium, copper, and aluminum, are common in environmental and occupational settings [8] [18]. Without the relatively unique Pb-Sb-Ba combination, distinguishing GSR particles from environmental contaminants becomes more difficult, requiring careful consideration of particle morphology and analytical context [15].

Enhanced Detection Strategies

To address these challenges, researchers have developed multi-modal approaches that combine inorganic and organic GSR analysis. The analysis of organic gunshot residues (OGSR) has gained prominence as a confirmatory technique when inorganic analysis is inconclusive [21] [16]. OGSR components include stabilizers (e.g., diphenylamine, methyl centralite, ethyl centralite), plasticizers (e.g., dimethyl phthalate, diethyl phthalate), and explosives (e.g., nitroguanidine, cyclonite) that can be detected regardless of the primer composition [21] [8].

The following decision framework illustrates the recommended analytical pathway for GSR analysis in the context of lead-free ammunition:

Case-to-case approach has emerged as a necessary strategy, where the evidentiary value is assessed based on the mutual consistency of particles found in a specific case rather than comparison to arbitrary classification schemes [15]. This approach requires more sophisticated data analysis and interpretation frameworks that consider the specific context of each case.

Advanced Analytical Techniques for Lead-Free GSR

Mass Spectrometry Methods

Liquid chromatography coupled with high-resolution mass spectrometry has demonstrated significant utility for OGSR analysis. A developed LC-QTOF method can identify 18 compounds commonly found in smokeless powders, including explosives (nitroguanidine, HMX, RDX), stabilizers (methyl centralite, ethyl centralite, diphenylamine), plasticizers (dimethyl phthalate, diethyl phthalate), and their metabolites [21]. This method enables confident identification through accurate mass measurements of both parent and fragment ions, with high sensitivity and specificity even at low concentration levels [21].

Single-particle inductively coupled plasma time-of-flight mass spectrometry (sp-ICP-TOF-MS) represents another advanced approach, capable of analyzing thousands of particles per minute with minimal sample preparation [20]. This technique can detect multi-elemental nanoparticles smaller than those typically identified by SEM-EDX, providing comprehensive elemental fingerprints of GSR particles that are particularly valuable for lead-free ammunition characterization [20].

Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS)

LIBS has emerged as a powerful complementary technique for GSR analysis, especially for shooting distance determination with lead-free ammunition. The iForenLIBS system can detect copper originating from ammunition casings and projectiles on fabric surfaces, enabling shooting distance estimation regardless of primer composition [19]. This method generates density maps that allow the evaluation of short, medium, and long-range shooting distances based on the distribution of copper and other elements [19].

LIBS offers several advantages for lead-free GSR analysis, including rapid analysis time (minutes versus hours for SEM-EDX), preservation of sample integrity for subsequent analysis, and simultaneous multi-element detection capability that is ideal for the varied compositions of lead-free ammunition [19] [8].

Experimental Protocols for Lead-Free GSR Analysis

Sample Collection and Preparation

GSR Collection Using Adhesive Stubs

- Materials: Aluminum SEM stubs (12.7 mm diameter) with carbon adhesive tabs [19]; Sterile tweezers; Evidence packaging containers

- Procedure:

- Using tweezers, remove protective covering from carbon adhesive surface

- Firmly press stub onto sampling surface (hands, clothing, or other substrates)

- Repeat approximately 100 dubbings to ensure representative particle collection [15]

- Place stub in clean container and seal properly to prevent contamination

- Document collection location, time, and conditions

- Note: Tape lifting is the most common technique for inorganic residues, while swabbing (with methanol-soaked cotton) may be preferred for organic residues [21]

Sample Preparation for SEM-EDX Analysis

- Materials: Sputter coater with graphite target; Conductive carbon thread; Vacuum desiccator

- Procedure:

- Mount collected stubs in specimen chamber

- Coat samples with conductive graphite layer using SCD 050 sputter or equivalent [15]

- Apply carbon coating sufficiently to prevent charging effects without immersing particles

- Store coated samples in vacuum desiccator until analysis to prevent contamination

SEM-EDX Analysis Protocol for Lead-Free GSR

Equipment Setup

- Scanning Electron Microscope (e.g., JSM-5800) with backscattered electron detector [15]

- Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectrometer (e.g., Oxford Instruments ISIS 300) [15]

- Automated particle analysis software (e.g., Phenom Perception GSR) [22]

Analysis Parameters

- Accelerating voltage: 20 kV [15]

- Working distance: 10-25 mm

- Spot size: optimized for resolution and counting statistics

- Magnification: 500-10,000× depending on particle size

Automated Particle Screening

- Define scan area by drawing circle on sample stub using optical view camera [22]

- Implement dual thresholding: first for particle detection, second for higher magnification imaging [22]

- Set particle size detection range: 0.5-50 μm

- Program automated EDS spectrum acquisition for each detected particle

- Execute scan frame-by-frame across entire defined area

Data Interpretation

- Manual verification of automatically classified particles

- Characterize particles by morphology (spherical, molten appearance) and composition

- Document all particles with elemental combinations including: Zn, Ti, Cu, Al, K, Si, Gd, Sn, Sr [19] [18]

- Record particle sizes, locations, and elemental ratios

LC-QTOF Method for Organic GSR Analysis

Chromatographic Conditions [21]

- Column: Zorbax Eclipse Plus C18 (100 mm × 4.6 mm, 1.8 μm)

- Mobile phase A: 2 mM ammonium acetate in UHP water

- Mobile phase B: methanol

- Gradient: 0 min (40% B), 0-10 min (40-95% B), 10-15 min (95% B), 15-15.10 min (95-40% B), 15.10-20 min (40% B)

- Flow rate: 0.4 mL/min

- Injection volume: 5 μL

- Column temperature: 30°C

Mass Spectrometry Parameters [21]

- Ionization: Electrospray ionization (ESI) in positive and negative modes

- Gas temperature: 300°C

- Drying gas: 8 L/min

- Nebulizer: 35 psig

- Sheath gas temperature: 350°C

- Sheath gas flow: 11 L/min

- Capillary voltage: 3500 V

- Nozzle voltage: 0 V

- Fragmentor voltage: 150 V

- Skimmer voltage: 65 V

- OCT 1 RF Vpp: 750 V

- Mass range: 50-1700 m/z

Target Analytes: Nitroguanidine (NQ), octogen (HMX), cyclonite (RDX), 2,4-dinitroanisole (DNAN), trinitrotoluene (TNT), pentaerythritol tetranitrate (PENT), methylcentralite (MC), ethylcentralite (EC), diphenylamine (DPA), dimethyl phthalate (DMP), diethyl phthalate (DEP), 2,4-dinitrotoluene (2,4-DNT), N-nitrosodiphenylamine (N-NDPA), 4-nitrodiphenylamine (4-NDPA), 2,4-dinitrodipheylamine (2,4-DNDPA), 2-nitrodipheylamine (2-NDPA), 2-amine-4,6-dinitrotoluene (4-ADNT), 4-amine-2,6-dinitrotoluene (2-ADNT) [21]

LIBS Protocol for Shooting Distance Determination

Equipment Setup [19]

- iForenLIBS system or equivalent LIBS instrument

- Disposable tips and plastic support platforms to prevent cross-contamination

- Computer with spectral analysis software

Analysis Parameters

- Laser wavelength: 1064 nm

- Laser pulse energy: 10-100 mJ

- Spot size: 50-200 μm

- Detection window: 1-5 μs after laser pulse

- Spectral range: 200-900 nm

- Number of shots per sample: 3-5 for statistical representativeness

Procedure for Shooting Distance Estimation

- Collect fabric samples from shooting experiments at known distances (e.g., 8-200 cm) [19]

- Mount samples on LIBS platform without additional preparation

- Perform raster scanning across sample surface with predefined pattern

- Detect copper emissions at 324.7 nm and 327.4 nm, plus other elements (Al, Ti, Zn, K) as needed

- Generate two-dimensional density maps of element distribution

- Correlate signal intensity and distribution pattern with shooting distance using calibration curves

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Lead-Free GSR Analysis

| Category | Specific Items | Research Function | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chromatography | Zorbax Eclipse Plus C18 column [21] | Separation of organic GSR components | 100 mm × 4.6 mm, 1.8 μm particle size |

| Ammonium acetate, LC-MS grade methanol [21] | Mobile phase components | 2 mM ammonium acetate in UHP water with methanol gradient | |

| Mass Spectrometry | Analytical standards: NG, NC, DPA, MC, EC, DMP, DEP, etc. [21] [16] | Identification and quantification of OGSR | Critical for method development and validation |

| Microscopy | Aluminum SEM stubs with carbon adhesive tabs [15] [19] | GSR particle collection and analysis | Standardized for automated SEM-EDX systems |

| Conductive graphite coating materials [15] | Sample preparation for SEM | Prevents charging effects during analysis | |

| Spectroscopy | LIBS disposable tips and platforms [19] | Prevention of cross-contamination in LIBS analysis | Essential for maintaining evidence integrity |

| Standard reference materials for calibration | Quality assurance and method validation | Required for quantitative analysis |

The transition to lead-free ammunition has fundamentally transformed GSR elemental profiles, necessitating significant methodological adaptations in forensic analysis. The characteristic Pb-Sb-Ba signature of conventional ammunition has been replaced by diverse elemental combinations including Zn, Ti, Cu, Al, K, and Si, depending on manufacturer-specific formulations. This shift requires integrated analytical approaches that combine advanced techniques such as SEM-EDX with modified classification criteria, LC-MS/MS for organic component detection, and emerging methods like LIBS and sp-ICP-TOF-MS. The experimental protocols detailed in this guide provide comprehensive methodologies for detecting and characterizing both inorganic and organic components of GSR from lead-free ammunition. As ammunition formulations continue to evolve, the forensic research community must maintain dynamic analytical frameworks capable of addressing these changes while upholding the rigorous evidentiary standards required in legal contexts.

The forensic analysis of Gunshot Residue (GSR) plays a pivotal role in the investigation of firearm-related crimes. The value of this evidence, however, extends far beyond its mere detection. Its scientific interpretation within the context of a case—determining whether an individual discharged a firearm, was an adjacent bystander, or acquired residues via indirect means—is entirely dependent on a robust understanding of three dynamic factors: persistence, transfer, and prevalence [23] [24]. This framework is not unique to GSR and forms a cornerstone of fundamental research in trace evidence microanalysis, including the study of explosives and other particulate materials. For GSR, the gradual shift in forensic interpretation from source-level (what is this particle?) to activity-level (how did this particle get here?) propositions underscores the critical need to quantify these factors through empirical data and probabilistic models [24] [25]. This technical guide synthesizes current research to provide scientists and researchers with a comprehensive overview of the key principles, quantitative data, and methodological approaches essential for the accurate interpretation of GSR evidence.

Fundamental Concepts in GSR Evidence Interpretation

GSR is a complex mixture of inorganic and organic components originating from the primer, propellant, and other ammunition constituents [24]. Inorganic GSR (IGSR), historically characterized by the presence of lead (Pb), barium (Ba), and antimony (Sb), is typically analyzed via Scanning Electron Microscopy with Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (SEM-EDS), which remains the "gold standard" for its ability to provide simultaneous morphological and chemical data [25] [8]. Organic GSR (OGSR), comprising nitrocellulose, nitroglycerin, and stabilizers, is increasingly analyzed using techniques like Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) to provide complementary orthogona l information [24] [13]. The interpretation of findings is hierarchically structured across three levels:

- Source Level: Concerns the identification of a particle as GSR.

- Activity Level: Addresses how the GSR was deposited on a surface or individual (e.g., firing a gun vs. secondary transfer).

- Offence Level: Pertains to the ultimate issue of guilt or innocence in a legal proceeding [24].

This guide focuses on the activity level, where the factors of transfer, persistence, and prevalence are most consequential. A significant contemporary challenge is the development of "non-toxic" or "lead-free" ammunition, which utilizes primer compositions based on elements like titanium (Ti) and zinc (Zn) [24] [8]. This shift complicates IGSR analysis and increases the potential for false positives, thereby elevating the importance of OGSR analysis and a more nuanced, integrated interpretation framework [24] [8].

Transfer of Gunshot Residue

The transfer of GSR particles refers to their movement from a source to a surface. This process is categorized to understand the various pathways through which an individual may acquire residues.

Mechanisms and Pathways of Transfer

- Primary Transfer: This is the direct deposition of GSR onto a surface or individual from the discharge plume of a firearm. This includes impact deposition (e.g., onto a shooter's hands) and fallout deposition (e.g., onto a bystander standing in the settling cloud of particles) [23] [13]. Recent studies using high-speed videography and laser sheet scattering have visually documented the complex flow dynamics of this plume, showing how GSR can disperse and settle in enclosed environments, potentially exposing multiple individuals [13].

- Secondary and Tertiary Transfer: This involves the indirect movement of GSR. Secondary transfer occurs when GSR is moved from a contaminated surface to a person (e.g., a suspect touching a contaminated police car interior or an officer's gloves transferring residue during an arrest). Tertiary transfer involves further steps removed from the original source [23] [25]. These pathways are critical for the defense proposition that a suspect acquired GSR without having fired a weapon.

Quantitative Data on GSR Transfer

Meta-analyses of transfer studies provide essential probabilistic data for activity-level interpretation. The following table summarizes key transfer rates:

Table 1: Quantitative Data on GSR Transfer Rates

| Transfer Scenario | Median Transfer Rate | Key Experimental Findings | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Secondary Transfer (Contact) | 1.1% to 3.3% (to hands) | Varies with type of contact; mock arrests show transfer is possible but generally low. | [23] |

| Secondary Transfer (Contact) | 1.2% to 18% (to sleeves) | Transfer to clothing can be significantly higher than to hands. | [23] |

| Transfer during Gun Handling | Median 61% (heavy handling) | The type of handling is a major factor; heavy gun handling results in substantial transfer. | [23] |

| Primary Transfer (Bystander) | Similar concentrations to shooter | Bystanders can have GSR particle counts on hands comparable to shooters after 15 minutes, making differentiation by count alone difficult. | [13] |

Persistence of Gunshot Residue

Persistence describes the duration for which GSR remains on a surface after initial deposition. It is a function of continuous loss due to activities and environmental factors.

Factors Affecting GSR Loss

Persistence is not static and is influenced by the substrate and an individual's activities. Key findings include:

- On Hands: GSR particles are rapidly lost from hands and are "unlikely to remain after a few hours of normal activity" [23]. One study specifically noted that particles on hands persist for less than two hours [24].

- On Clothing: The process of loss is similar but generally occurs at a slower rate than on hands, making clothing a potentially more reliable substrate for sampling after a time delay [23].

- Airborne Persistence: A novel area of research using real-time atmospheric samplers has revealed that GSR particles can remain suspended in the air for several hours after a shooting event in an enclosed room, creating a risk of contamination for anyone entering that space [13].

Experimental Persistence Data

The following table summarizes persistence data from experimental studies:

Table 2: Experimental Data on GSR Persistence

| Substrate | Persistence Timeline | Experimental Context | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hands | < 2 hours | Particles are continuously lost during normal activity. | [24] |

| Gloves | Slower rate than hands | Study of persistence on assembly-type gloves. | [23] |

| Airborne Particles | Up to several hours | Measured using particle counters in an enclosed room post-discharge. | [13] |

Prevalence and Background Levels of GSR

Prevalence refers to the occurrence of GSR-like particles in the general environment or on individuals not involved in a shooting. Understanding background levels is crucial for assessing the potential for false positives.

- Environmental and Occupational Sources: Particles with elemental compositions similar to GSR can originate from sources such as brake pad dust, industrial processes, and pyrotechnics (fireworks) [7] [8]. Automotive mechanical parts often contain Sb and Ba, which can form particles morphologically and chemically consistent with GSR [23].

- Police Equipment: Studies have documented the presence of GSR on the gloves and equipment of police officers who have handled their firearms at the start of a shift, representing a potential vector for contamination and secondary transfer to suspects [23].

- OGSR in the Environment: Certain OGSR components, like 2,6-dinitrotoluene (2,6-DNT), are more common in non-shooting environments. However, the detection of specific compounds like trinitroglycerine (TNG) in conjunction with ethyl centralite (EC) is considered to have stronger evidentiary value due to its rarity in background environments [7].

Prevalence Studies and Evidential Value

Surveys across various population groups generally indicate that the prevalence of characteristic GSR particles on the hands of the general public is low [23] [7]. This low background prevalence strengthens the evidential value of finding multiple characteristic GSR particles on a suspect's hands shortly after a shooting. However, the probabilistic assessment must always consider the possibility of occupational exposure or transfer from contaminated surfaces.

Analytical Frameworks for Activity-Level Interpretation

Moving from source identification to activity-level inference requires formal interpretive frameworks. The Bayesian approach and the calculation of Likelihood Ratios (LRs) are increasingly advocated for this purpose [24].

The Likelihood Ratio Framework

The LR framework weighs the probability of the evidence under two competing propositions posed by the prosecution (Hp) and defense (Hd). For GSR, a typical pair of activity-level propositions would be:

- Hp: The individual discharged a firearm.

- Hd: The individual acquired the residue by secondary transfer (or was a bystander).

The LR is expressed as: LR = P(E | Hp, I) / P(E | Hd, I), where E is the evidence (e.g., number and type of GSR particles found), and I is the background case information [24]. An LR greater than 1 supports the prosecution's proposition, while an LR less than 1 supports the defense's proposition.

Bayesian Networks for GSR Interpretation

Bayesian Networks (BNs) are graphical models that represent the complex probabilistic relationships between variables and are considered highly suitable for interpreting GSR evidence at the activity level [24]. They can integrate data on transfer, persistence, prevalence, and case-specific circumstances (e.g., time since event, activities of the suspect).

The following diagram illustrates a simplified Bayesian Network for GSR evidence evaluation:

Simplified Bayesian Network for GSR Evidence

Advanced Experimental Protocols in GSR Research

Cutting-edge research employs multi-method approaches to unravel the complexities of GSR production and dispersion. The following workflow details a novel protocol from recent literature.

Multi-Sensor Workflow for GSR Deposition and Transfer Studies

A recent study employed an integrated protocol to investigate GSR flow and deposition mechanisms [13]. The objective was to simultaneously measure airborne particle dynamics and visualize GSR plumes to understand primary transfer to shooters, bystanders, and passersby.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials for GSR Flow Studies

| Item / Solution | Function in the Experiment | Analytical Technique |

|---|---|---|

| Firearms & Ammunition | Source of GSR particles; variables include caliber, number of shots. | N/A |

| Custom Atmospheric Particle Samplers | Measure population and size distribution of airborne particles in real-time before, during, and after discharge. | Particle Counting/Sizing |

| High-Speed Video Camera | Captures visual and qualitative information about the flow of GSR. | Videography |

| Laser Sheet Scattering System | Visually illuminates the GSR plume for qualitative flow analysis. | Laser Scattering |

| Carbon Adhesive Stubs | Collect IGSR particles from surfaces for confirmatory analysis. | SEM-EDS |

| Swabs (e.g., Cotton/Viscose) | Collect OGSR residues from surfaces for confirmatory analysis. | LC-MS/MS |

The experimental workflow is summarized in the following diagram:

Multi-Sensor Experimental Workflow for GSR Studies

Key Experimental Steps:

- Controlled Discharge: Conduct firearm discharges in various environments (indoor, outdoor, semi-enclosed) using different firearms and ammunition.

- Real-time Atmospheric Sampling: Deploy particle counters and sizing systems at multiple distances to measure the concentration and size distribution of airborne GSR over time.

- Plume Visualization: Use high-speed videography synchronized with a laser sheet to visually track the expansion, flow, and settlement of the GSR cloud, especially around mock shooters and bystanders.

- Surface Sampling: Use carbon stubs and swabs to collect residues from surfaces, hands, and clothing at predetermined intervals and locations.

- Confirmatory Analysis: Analyze stubs via SEM-EDS to confirm the presence and composition of IGSR particles. Analyze swabs via LC-MS/MS to identify and quantify organic compounds.

- Data Integration: Correlate data from all sensors to build a comprehensive model of GSR production, transport, and deposition.

The accurate interpretation of GSR evidence is fundamentally dependent on a deep and quantitative understanding of persistence, transfer, and prevalence. This whitepaper has detailed how these factors interact to determine the evidential value of a GSR finding. The field is moving decisively towards probabilistic, activity-level evaluation using Likelihood Ratios and Bayesian Networks, which provide a transparent and logically robust framework for communicating findings to the court [24]. Future challenges, particularly the widespread adoption of non-traditional ammunition, will necessitate a greater reliance on orthogonal methods that combine IGSR and OGSR analysis [24] [8]. For researchers and forensic scientists, bridging the gap between novel research and routine practice requires a concerted focus on generating standardized, large-scale data on these key factors, ensuring that the interpretation of GSR evidence remains both scientifically sound and forensically relevant.

Analytical Techniques in GSR Microanalysis: From Gold Standard to Novel Methods

Gunshot residue (GSR) analysis is a specialized branch of forensic science that focuses on the trace evidence left behind following the discharge of a firearm. When a firearm is discharged, it releases a cloud of microscopic particles that deposit on surrounding surfaces, including the hands of the shooter. GSR consists of both organic components (originating from propellants and lubricants) and inorganic components (originating from the primer, case, and barrel) [22]. The inorganic telltale signs that indicate a firearm has been discharged are particles containing a combination of lead (Pb), barium (Ba), and antimony (Sb), which primarily originate from the primer compound [22]. The primary explosion compound is typically lead styphnate, while barium nitrate and antimony sulfide act as the oxidation and reduction compounds, respectively [22].

The detection of GSR confirms that a firearm was discharged, but the analysis provides further crucial information. By studying the distribution patterns of residues, forensic experts can determine the number of shots fired and estimate the proximity between the firearm and its target [22]. Ultimately, GSR analysis can link individuals or objects to the action of discharging a firearm, playing a pivotal role in identifying potential perpetrators, reconstructing crime events, and corroborating or challenging witness testimony [22].

SEM-EDS: The Established Gold Standard

Scanning Electron Microscopy with Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (SEM-EDS) has emerged as the internationally accepted gold standard for the analysis of inorganic gunshot residue (IGSR) [22] [16]. It was introduced for this purpose in 1974 and has since become the cornerstone technique due to its unique capabilities [16].

SEM-EDS stands out as the superior method for several key reasons. It allows investigators to visualize and characterize GSR particles at the nanoscale level, enabling the precise identification of unique morphological features (such as fast-cooled droplets of molten materials) that are characteristic of GSR [22]. This high resolution ensures accurate differentiation between GSR and other similar substances, reducing the risk of false positives [22]. Furthermore, the integrated EDS facilitates simultaneous elemental analysis on the individual particle level, allowing for the unambiguous detection of the characteristic elemental signature of primer-derived particles [22]. Finally, SEM-EDS is a non-destructive technique, meaning the sample is preserved for additional testing or reexamination if necessary, making it a reliable and invaluable tool for forensic investigations [22].

The technique's status as the gold standard is historically rooted in the reliability of detecting lead (Pb), antimony (Sb), and barium (Ba) in discrete particles from the primer [16]. However, the forensic community faces new challenges with the increasing commercialization of lead-free and heavy metal-free ammunition, which can potentially lead to false negative results with standard SEM-EDS analysis [16]. Additionally, IGSR-like particles can be derived from environmental and occupational sources such as brake linings, fireworks, and paints, presenting a risk of false positives in some situations [16]. These limitations have spurred interest in complementary techniques, particularly for the analysis of organic gunshot residues (OGSR).

Comparison of GSR Analytical Techniques

Table 1: A comparison of different analytical techniques used in Gunshot Residue analysis.

| Technique | Target Components | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| SEM-EDS [22] [16] | Inorganic (IGSR) | Non-destructive; reveals morphology & composition; automated analysis | Limited utility for lead-free ammunition; potential for environmentally-sourced false positives |

| Mass Spectrometry [16] | Organic (OGSR) | High selectivity & sensitivity; can identify specific explosives & additives | Destructive technique; requires complementary technique for IGSR |

| Colorimetric Tests [22] | Inorganic | Early, simple tests | Prone to artifacts from environmental contamination |

| Neutron Activation Analysis [22] | Inorganic | Detects Sb and Ba | Requires large sample & nuclear reactor; slow |

| Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy [22] | Inorganic | Detects Pb, Ba, Sb in trace samples | Expensive, destructive, and slow |

Automated SEM-EDS and the ASTM E1588 Standard

To ensure accuracy and reproducibility across forensic laboratories worldwide, technical standards have been established. ASTM International released standard E1588-07: Standard Guide for Gunshot Residue Analysis by Scanning Electron Microscopy/Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectrometry [26]. This guide covers the analysis of GSR by SEM/EDS using both manual and automated methods [26].

A critical requirement of the ASTM E1588 standard is that analysis must be performed through automated software control to screen the sample for candidate GSR particles [22]. Automation ensures an accurate and repeatable workflow that is free from user bias and generates actionable, standardized reports [22]. The standard acknowledges that while the analysis can be performed "manually" by an operator, a significant portion can be controlled by pre-set software functions requiring little intervention [26].

The Automated GSR Workflow

Automated SEM-EDS systems, such as those utilizing the Phenom Perception GSR software, consolidate imaging and analysis functions into a simplified, accessible interface compliant with ASTM E1588 [22]. The typical automated workflow is as follows:

- Sample Collection: GSR is collected from surfaces like hands, clothing, or vehicles using an aluminum stub with a carbon adhesive tape in a simple tape lift-off method [22].

- Defining Scan Area: The user defines the analysis area on each sample stub by drawing a circle on an optical view camera. The system automatically saves the X-Y coordinates and working distance for each location [22].

- Automated Particle Screening: The system automatically segments the sample stub into fields and scans them frame-by-frame. It uses a backscattered electron detector (BSD) to detect particles based on their atomic contrast [22].

- Elemental Analysis: When a particle is detected, the system automatically pauses to acquire an EDS spectrum to determine its elemental composition [22].

- Data Storage and Mapping: Images and EDS spectra of each particle are saved. A map indicating the location of every detected particle within the scan area is generated [22].

- Manual Confirmatory Analysis: Once the automated screening is complete, manual review is necessary to verify the classification of candidate GSR particles based on both their morphology and elemental signature [22].

Diagram 1: Automated SEM-EDS GSR analysis workflow per ASTM E1588.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for SEM-EDS GSR Analysis

| Item / Reagent | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Carbon Adhesive Tabs | Mounting and securing particulate samples on SEM stubs for analysis; provides a conductive path [22]. |

| Aluminum SEM Stubs | Standard substrate for holding samples within the SEM chamber; compatible with automated stage systems [22]. |

| Phenom Perception GSR Software | Automated particle analysis software that controls the SEM-EDS system to execute ASTM E1588-compliant workflows [22]. |

| Certified Reference Materials | Particles with known composition and morphology used for instrument calibration and validation of analytical methods. |

| Backscattered Electron Detector | Critical detector for identifying high-atomic number particles (like GSR) based on material contrast during automated screening [22]. |

| Cerium Hexaboride (CeB6) Electron Source | Provides a brighter and more stable electron beam compared to tungsten, enabling high-resolution imaging over long durations [22]. |

The microanalysis of gunshot residue (GSR) represents a critical frontier in forensic chemistry, essential for reconstructing firearm-related events and linking suspects to criminal activities. Traditional analysis, particularly via scanning electron microscopy with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDS), has long served as the accepted standard for characterizing the inorganic components (IGSR) based on elemental composition (Pb, Ba, Sb) and particulate morphology [16] [3]. However, the forensic landscape is shifting due to the proliferation of lead-free, "non-toxic" ammunition, which eliminates characteristic heavy metal signatures and increases the potential for false-negative results [16] [8] [3]. Concurrently, the limitations of traditional methods—including their destructive nature, time-consuming processes, and inability to analyze organic GSR (OGSR)—have driven research into advanced spectroscopic techniques [27] [8].

Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS), Raman Spectroscopy, and Ion Mobility Spectrometry (IMS) have emerged as powerful tools capable of addressing these analytical gaps. These techniques offer a paradigm shift towards rapid, sensitive, and complementary analysis of both inorganic and organic constituents of GSR. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of these three core spectroscopic methods, detailing their fundamental principles, experimental protocols, and data interpretation workflows. The objective is to frame their application within fundamental research on microanalysis, highlighting their combined potential to deliver a more comprehensive and forensically robust characterization of gunshot residue and explosive materials.

Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS)

Principle: LIBS is a form of atomic emission spectroscopy that utilizes a high-energy pulsed laser to ablate a microscopic portion of the sample, generating a transient plasma with temperatures exceeding 10,000 K [28]. This plasma atomizes and excites the constituent material. As the plasma cools, excited electrons return to lower energy states, emitting element-specific wavelengths of light, which are dispersed and detected to provide a quantitative and qualitative elemental fingerprint [29] [28].

Strengths and Forensically Relevant Parameters:

- Minimal Sample Preparation: Solids, including GSR collected on adhesive stubs, can be analyzed directly [30] [28].

- Rapid Analysis and High Throughput: A single laser pulse can provide a full elemental spectrum in seconds, enabling high-throughput screening [29].

- Spatial Resolution: Capable of single-particle targeting and mapping of elemental distribution across a sample surface [30] [31].

- Portability: Systems can be miniaturized for field-deployable, on-scene analysis [30] [29].

Raman Spectroscopy

Principle: Raman spectroscopy is a molecular vibrational technique based on the inelastic scattering of monochromatic light. When a laser interacts with a sample, a tiny fraction of the scattered photons shifts in energy corresponding to the vibrational modes of the molecular bonds present. This resulting "Raman shift" provides a unique molecular fingerprint, allowing for the identification of organic compounds and functional groups [27] [31].

Strengths and Forensically Relevant Parameters:

- Non-Destructive Analysis: The sample remains intact for subsequent analysis, a crucial factor in evidence preservation [27] [31].

- Molecular Specificity: Excellent for identifying organic components such as stabilizers (e.g., diphenylamine, ethyl centralite) and explosives (e.g., nitroglycerin) in OGSR [27] [8].

- Hyperspectral Imaging: Can be used for rapid imaging of macroscopic GSR particles on complex substrates [31].

- Complementarity with LIBS: Raman and LIBS can be performed sequentially on the same particle, providing correlated molecular and elemental data from a single micro-sample [31].

Ion Mobility Spectrometry (IMS)

Principle: IMS separates ionized gas-phase molecules based on their size, shape, and charge as they drift under the influence of an electric field through a buffer gas. The measured drift time is converted to a collision cross-section, providing a characteristic identifier for the analyte [16] [8].

Strengths and Forensically Relevant Parameters:

- High Sensitivity: Capable of detecting trace levels of explosive and propellant vapors and particles [16] [8].

- Rapid, Real-Time Analysis: Provides results in near real-time, making it suitable for security screening and rapid field testing [16].

- Portability: Handheld IMS devices are commercially available and widely used in the field [8].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Spectroscopic Techniques for GSR

| Parameter | LIBS | Raman Spectroscopy | Ion Mobility Spectrometry (IMS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Information | Elemental Composition | Molecular Vibrational Fingerprint | Ion Drift Time / Collisional Cross-Section |

| Analysis Target | Inorganic GSR (IGSR) | Organic GSR (OGSR) & some inorganic | Organic GSR (OGSR), Explosives |

| Sample Throughput | Very High (seconds/sample) | Moderate to High | Very High (near real-time) |

| Destructive? | Minimally Destructive (ablation) | Non-Destructive | Destructive (sample is consumed) |

| Key Forensic Applications | Elemental mapping, shooter identification, ammunition differentiation [29] [31] | Ammunition manufacturer identification, particle identification [27] [31] | Rapid screening for explosives and propellants [16] [8] |

| Notable Limitations | Matrix effects, spectral interferences [28] | Fluorescence interference from substrates | False positives from environmental contaminants [31] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized GSR Sample Collection

A critical precursor to all laboratory analysis is the integrity of sample collection. The prevalent method, as outlined in Brazilian police protocols and similar to practices worldwide, involves using a 3M double-sided transparent adhesive tape to swab the hands of a suspect [29]. The tape is applied to the dorsum and palms of the hands, focusing on the thumb and index finger, to collect loose GSR particles. The tape is then placed on a rigid substrate, such as an aluminum stub, for transport and direct analysis under microscopy or spectroscopic instrumentation [30] [29].

Detailed LIBS Analytical Protocol

1. Instrument Calibration and Setup:

- A pulsed Nd:YAG laser (typically at 1064 nm fundamental or its harmonics) is used as the ablation source [28].

- The laser is focused onto the sample surface using a plan-convex lens to a spot size of a few micrometers to tens of micrometers [30].

- An argon or helium gas flow is often directed at the ablation point to enhance analyte signal intensity by suppressing plasma background and preventing atmospheric oxygen interaction [30].

- The emitted light is collected by a lens or fiber optic cable and coupled to a high-resolution spectrometer (e.g., Czerny-Turner configuration) with an ICCD (Intensified Charge-Coupled Device) detector for time-gated signal acquisition [28].

2. Data Acquisition for GSR:

- The sample stage is manipulated to target individual particles of interest, which can be visually located via an integrated camera system [30].

- Multiple laser pulses (typically 3-5) are fired at each analysis location to remove surface contamination and obtain a representative spectrum, averaging the resulting emissions to improve the signal-to-noise ratio.

- Key elemental emission lines for IGSR analysis include: Ba (455.4 nm, 493.4 nm), Pb (405.8 nm), Sb (259.8 nm, 323.0 nm), and Cu (324.7 nm, 327.4 nm) [29].

3. Data Processing and Machine Learning:

- Raw spectra undergo preprocessing: baseline correction, normalization (e.g., vector normalization), and peak integration [29].

- For classification (e.g., Shooter vs. Non-Shooter), machine learning algorithms such as Support Vector Machine (SVM) are trained on the spectral data. A probabilistic-based protocol can then classify samples with high specificity, introducing an "Undefined" category for uncertain results to minimize false positives/negatives [29].

Detailed Raman Spectroscopy Analytical Protocol

1. Two-Step Detection and Identification:

- As developed by Lednev et al., a two-step method is highly effective [27].

- Step 1: Fluorescence Hyperspectral Imaging. The sample area is first scanned using fluorescence imaging to detect potential GSR particles, which often exhibit strong fluorescence.

- Step 2: Confirmatory Raman Spectroscopy. Identified fluorescent particles are then targeted for Raman analysis. A 785 nm laser wavelength is commonly used to minimize fluorescence interference.

2. Data Acquisition:

- The Raman spectrometer is calibrated daily using a silicon wafer standard (peak at 520.7 cm⁻¹).

- Spectra are collected with a high signal-to-noise ratio, employing multiple accumulations (e.g., 10-30 seconds per accumulation).

- Characteristic peaks for OGSR include: Nitroglycerin (NG) (~855 cm⁻¹, 1275 cm⁻¹), Diphenylamine (DPA) (~1000 cm⁻¹, 1300 cm⁻¹), and Ethyl Centralite (EC) (~1000 cm⁻¹, 1600 cm⁻¹) [31].

3. Chemometric Analysis:

- Advanced statistical methods (e.g., Principal Component Analysis - PCA) are applied to Raman datasets to differentiate between GSR from different ammunition types and manufacturers, overcoming the inherent visual similarity of spectra [27] [31].

Sequential LIBS/Raman Analysis Protocol

For maximal information from a single microscopic particle, a sequential analytical protocol is recommended [31]:

- A particle of interest is first located and documented using high-resolution optical microscopy.

- Raman analysis is performed to obtain a molecular fingerprint, confirming the particle as OGSR and identifying its organic constituents.

- LIBS analysis is subsequently performed on the exact same particle to obtain its elemental signature. This correlated data provides a powerful, multi-attribute fingerprint for highly selective ammunition differentiation.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the integrated experimental pathway from sample collection to data analysis using these complementary techniques.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for GSR Microanalysis

| Item | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 3M Double-Sided Adhesive Tape | Standardized collection of GSR particles from hands, clothing, and surfaces. | Compatible with SEM-EDS, LIBS, and Raman analysis protocols; prevents particle loss [29]. |

| Aluminum Sampling Stubs | Rigid substrate for mounting tape-borne GSR samples for instrumental analysis. | Standard size ensures compatibility with automated stages in SEM and LIBS instruments [30]. |

| Argon Gas (High Purity) | Inert atmosphere for LIBS plasma enhancement. | Flow over the ablation site increases signal intensity and stability by reducing atmospheric interference [30]. |

| Silicon Wafer Standard | Daily wavelength calibration of Raman spectrometers. | Provides a sharp, characteristic Raman peak at 520.7 cm⁻¹ for accurate instrument calibration [31]. |

| Lead-Free Ammunition Reference Materials | Critical control samples for method development and validation. | Essential for creating spectral libraries and training machine learning models to address modern ammunition challenges [8] [3]. |